The Rural Homes of Marcelo Ferraz and Francisco Fanucci

Where our sertão remains

Every happy little house

Still neighbors a stream

And still harbors its arborsWhere our sertão remains

Every happy little home

Cooks on the coal cooker

The wood stove’s still blown

[…]

Where sertão remains

Every little house is glad

for on the evenings we get our Hail-Mary

And the pleasure of being alone

‘Casinha feliz’, lyrics by Gilberto Gil [1]

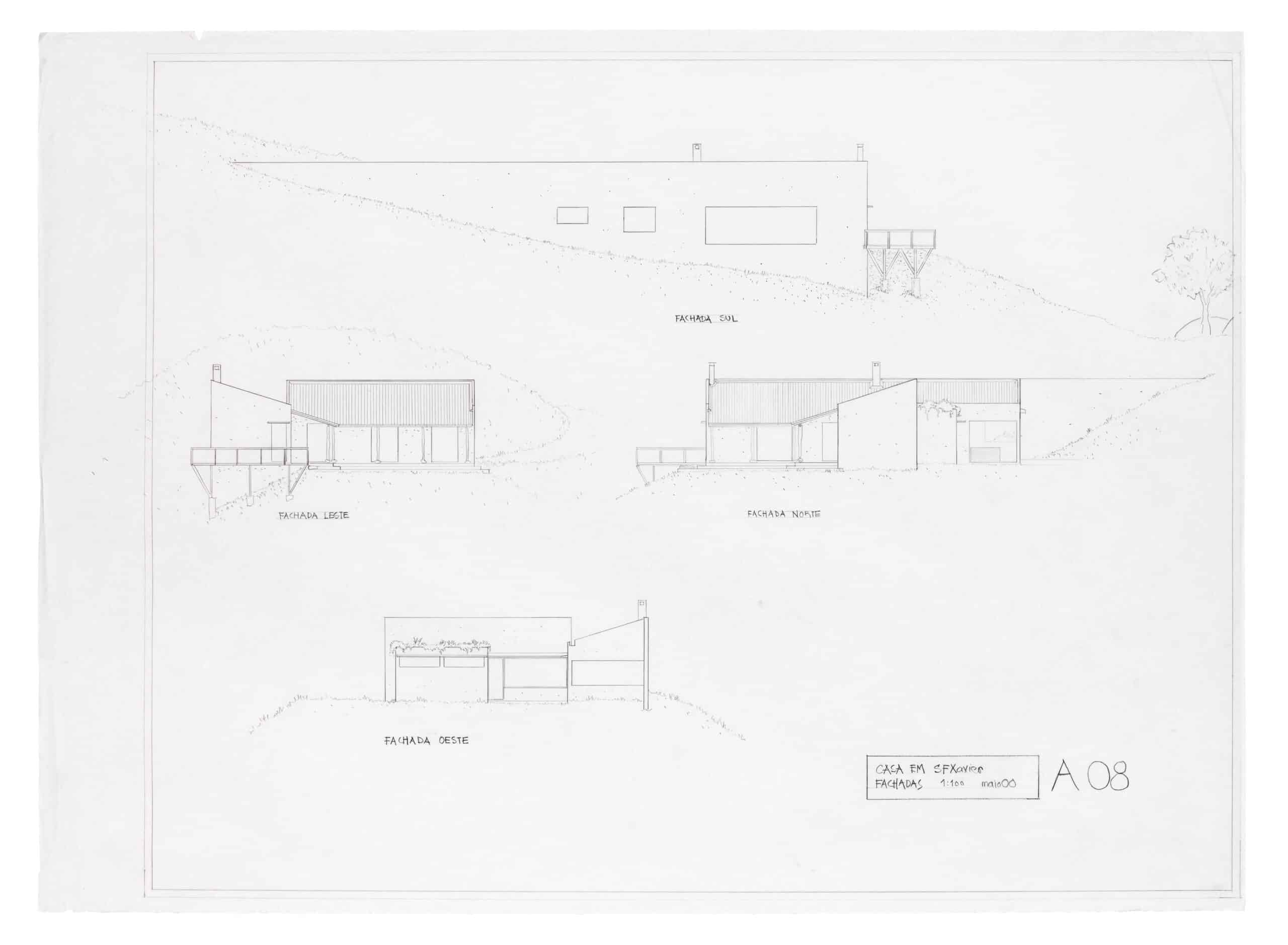

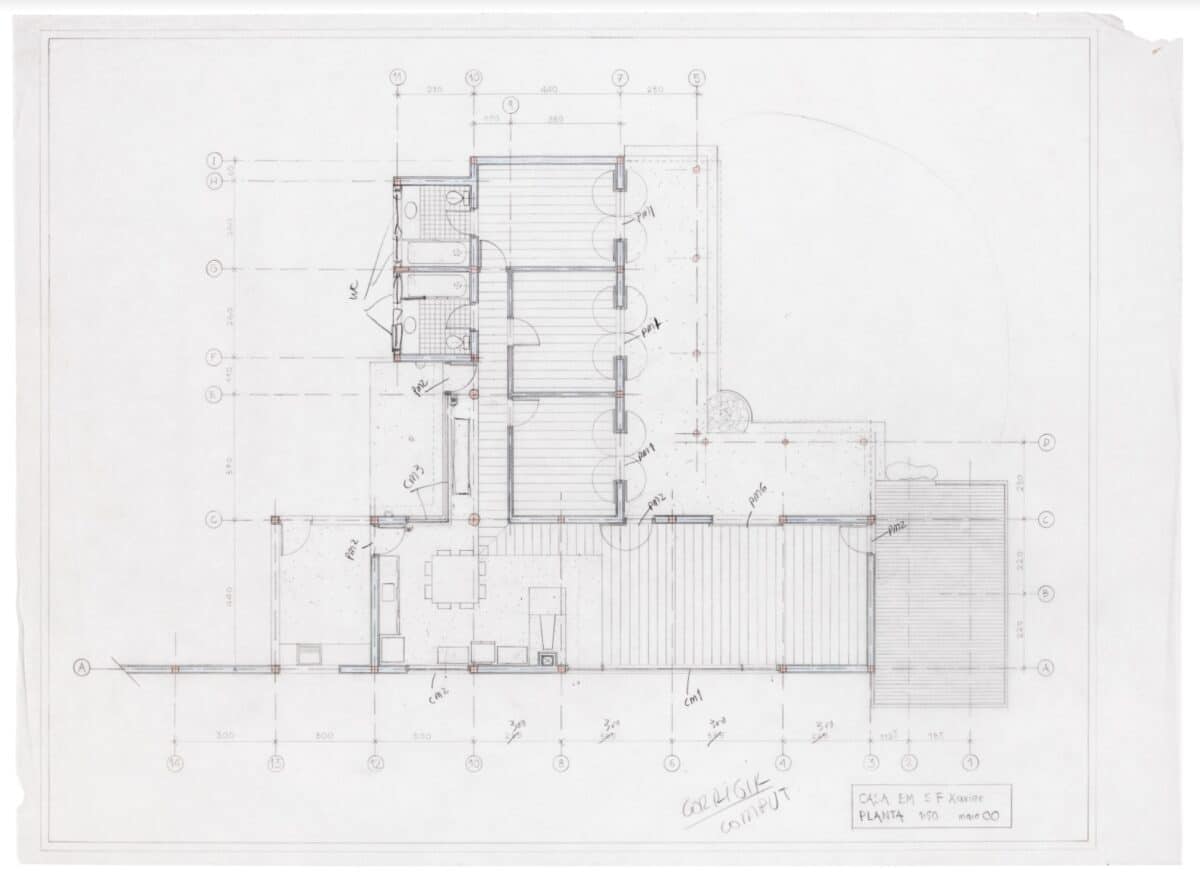

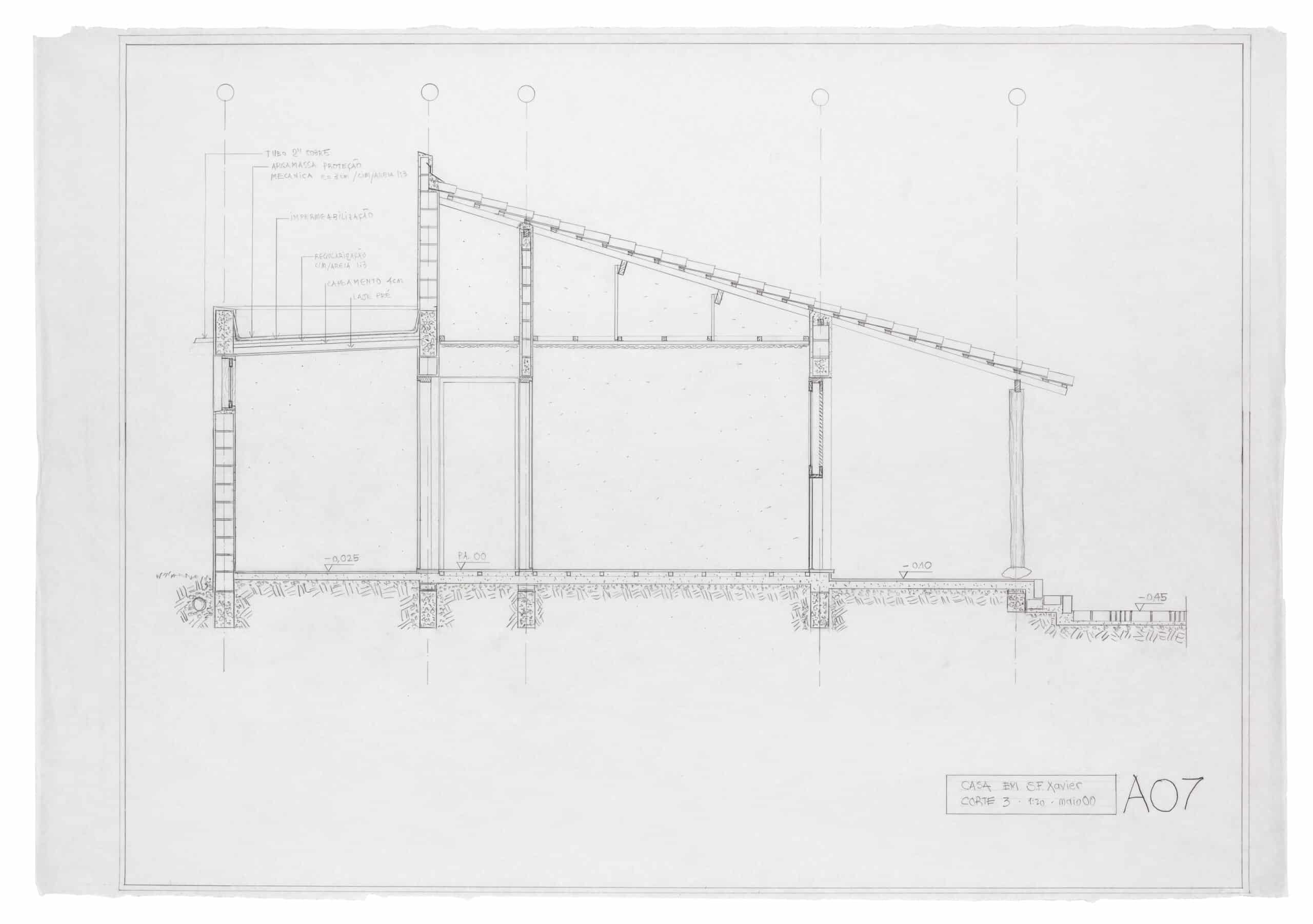

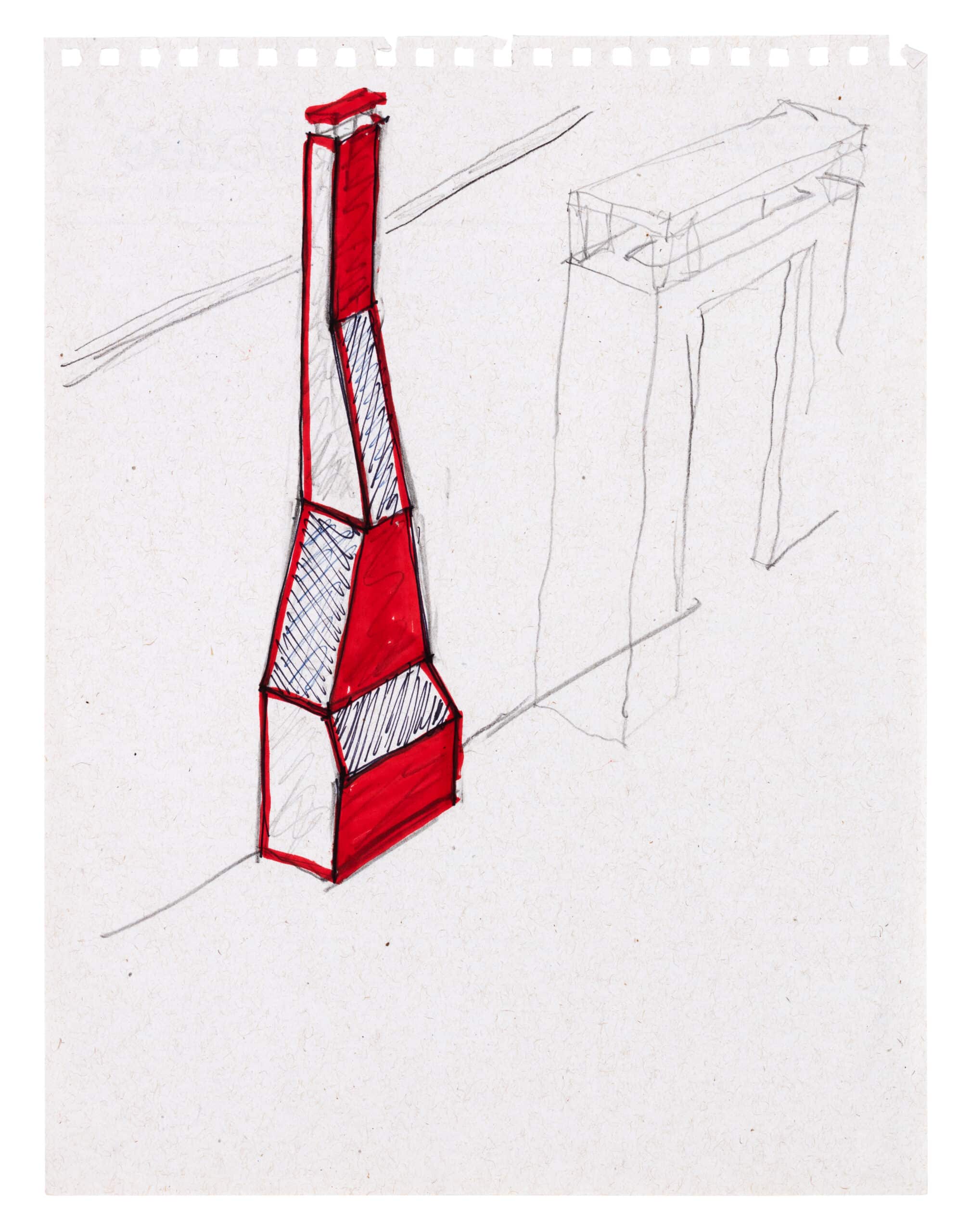

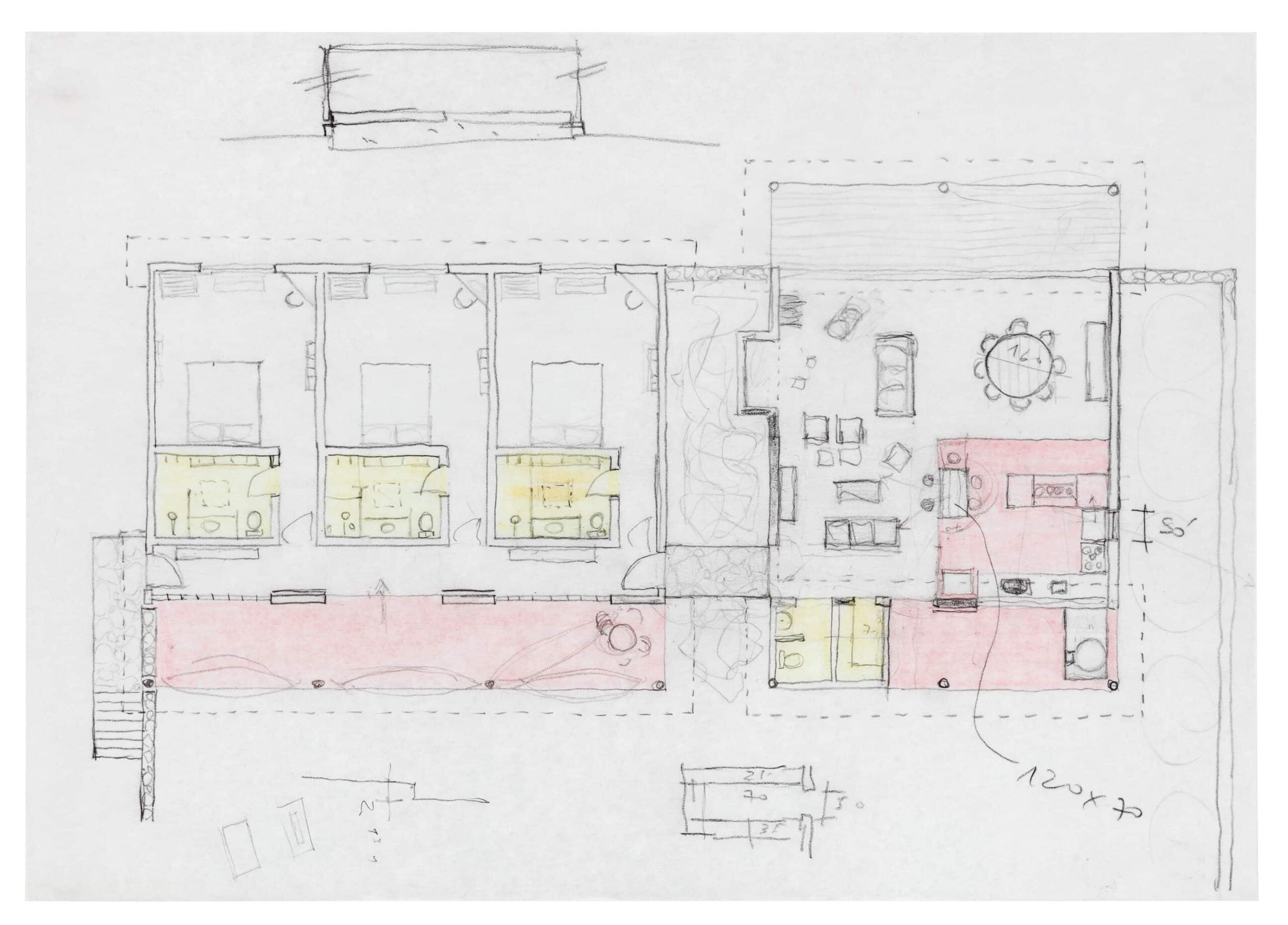

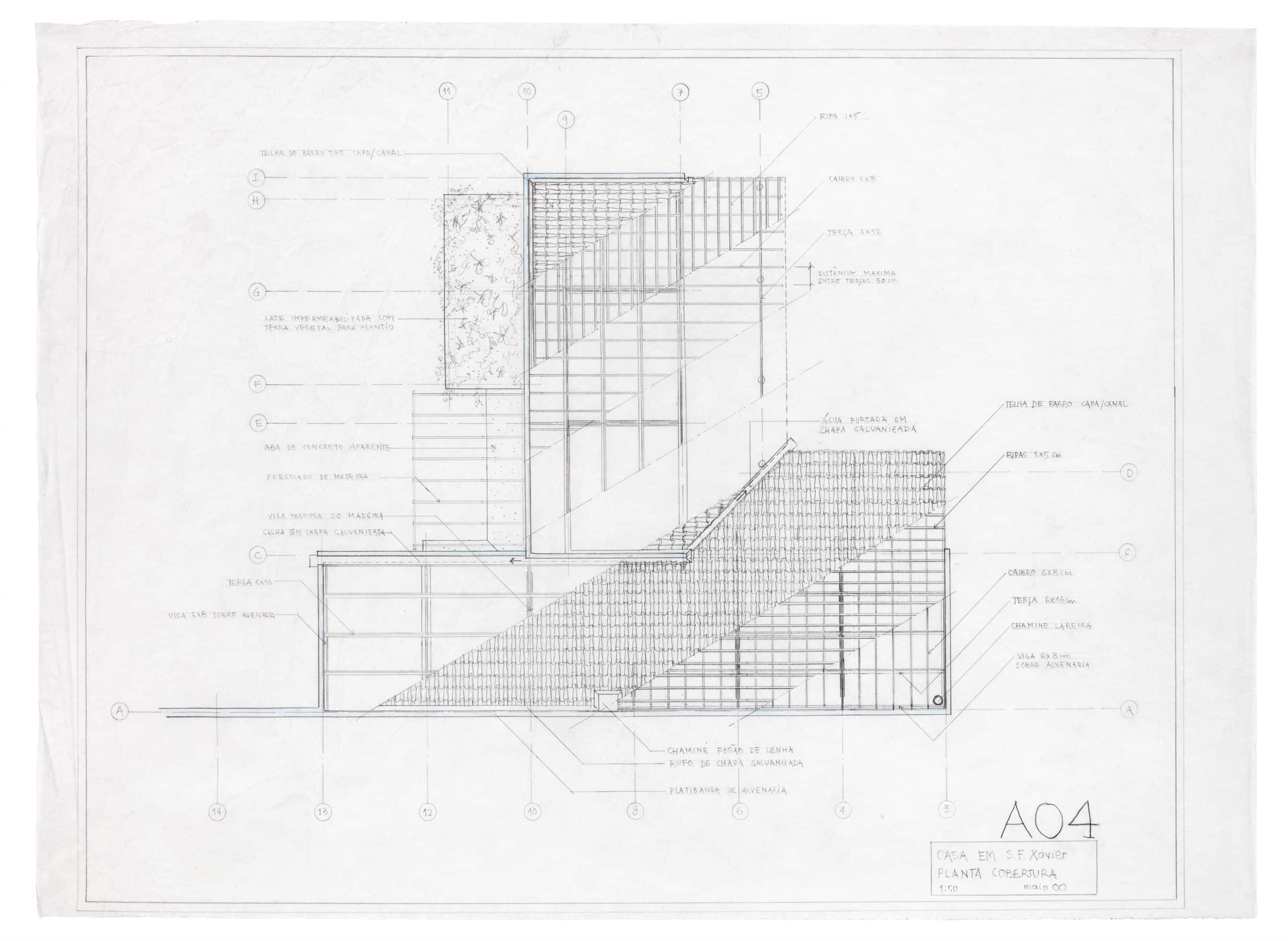

In São Francisco Xavier in the Mantiqueira Mountain Range, near the state line of Minas Gerais, lies the Mantiqueira House (2000), a project designed by the architect Francisco Fanucci. [2] Nestled at the top of one of the great hills, the building balances itself on the side of a steep rise, on partially earth-worked grounds. Shaped like an ‘L’, the house is organised into two wings. It has three portholes that open onto the South landscape, where tumultuous hills resemble a stormy sea. In the living room, the largest opening, a great tear of transparent glass, has two other windows in its extremities for ventilation. To the left, the fireplace room connects to the exterior veranda. In the kitchen, to the right, there is another window and a wood-burning stove on an old-style red burnt cement floor. [3] Out of this same side, there is a door/window to the porch, equipped with a wood stove for barbecue and pizza.

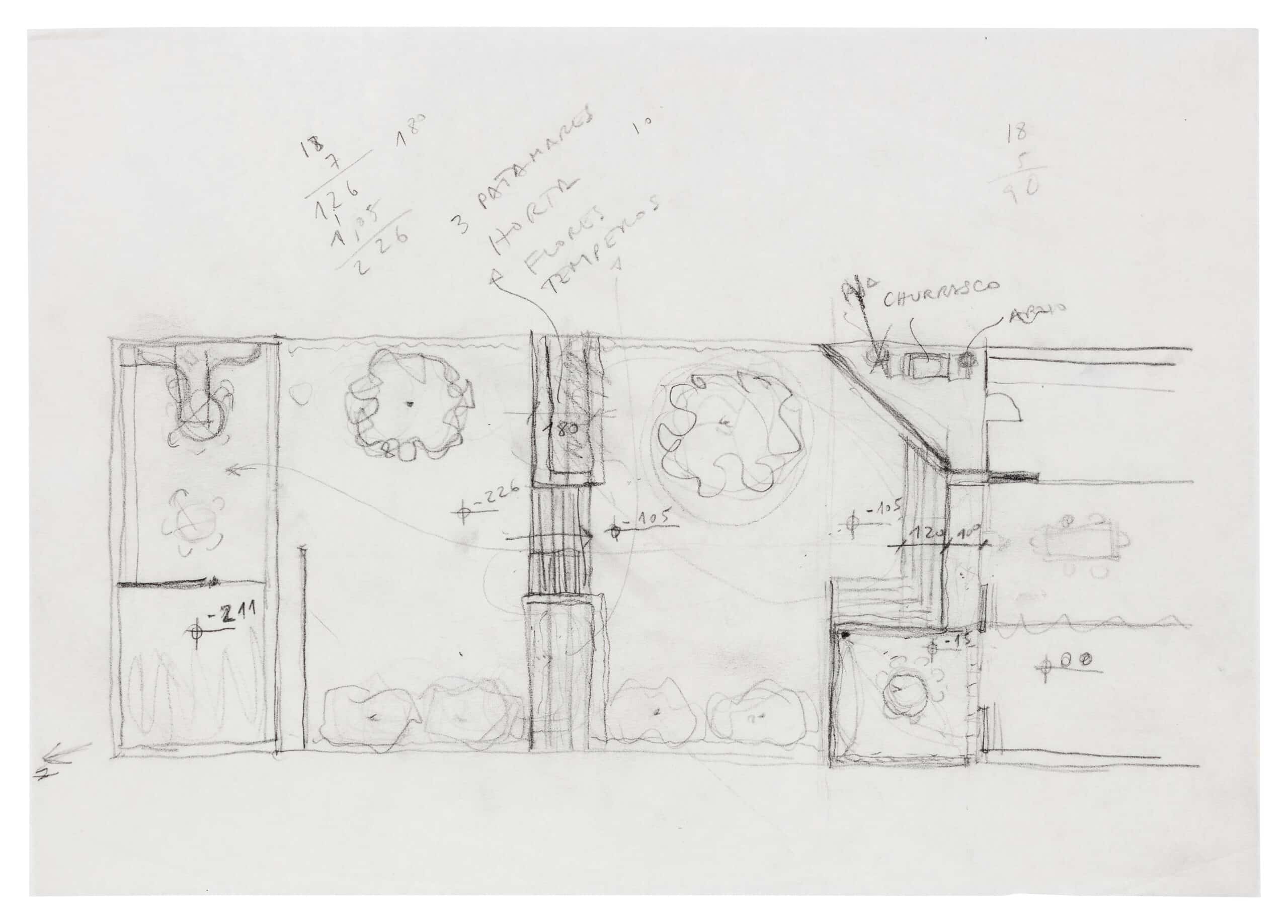

From afar, only a whitewashed wall spliced to the dividing wall can be seen on this side, a kind of white horizontal blade that slowly vanishes from the bottom-up until it is gone, in the ascending terrain. [4] It is similar to the landscape designs of Richard Serra. [5] The facade is abruptly subsided by the folding of the unit in half, with the private area of the bedrooms turning ninety degrees in a domestic dialogue with its surrounding. The roofs of the two wings are tilted in a convergent manner, sheltering the ‘L’ shaped porch that is connected to rooms and halls by doors. The result is a building that’s exposed on one section and concealed on another, and partially closed-off on the other two sides by vegetation to make a courtyard. This image is reinforced by the semicircular use of cobblestones. On the other side of the bedroom wing, there’s a section with bathrooms and an orchard. Here, another patio is formed by the other three sides by the living room veranda, the steep hill, and afforestation.

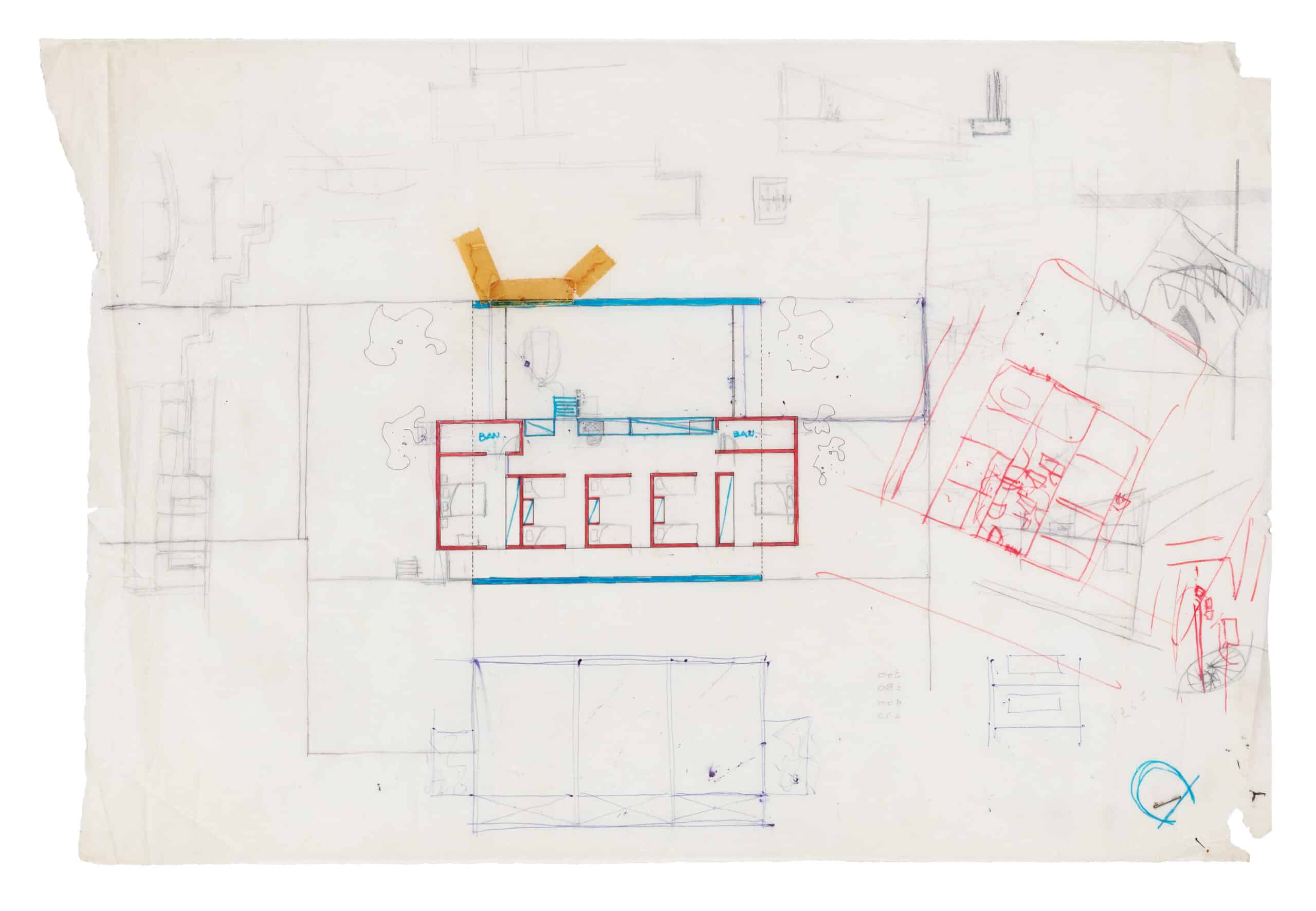

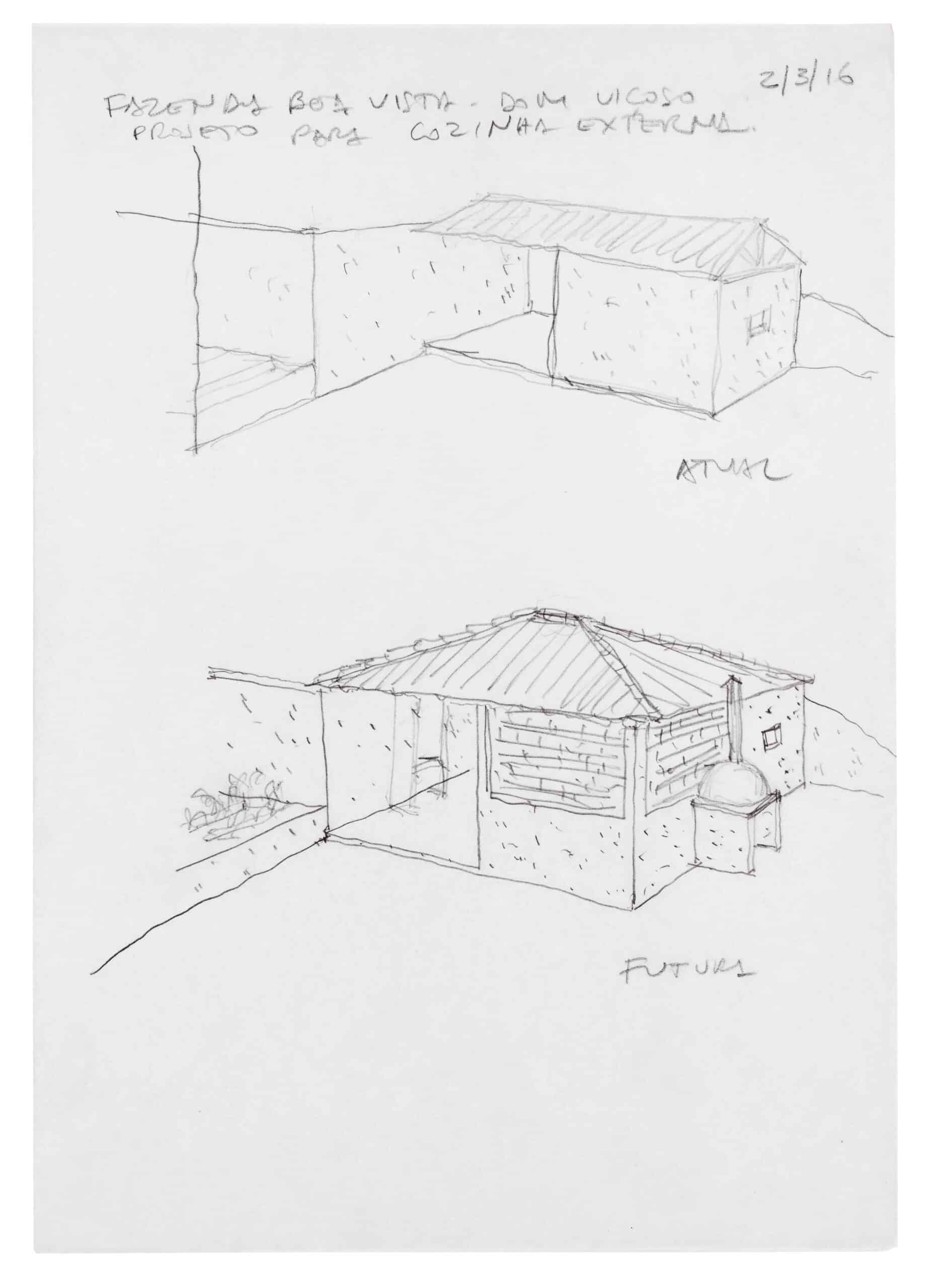

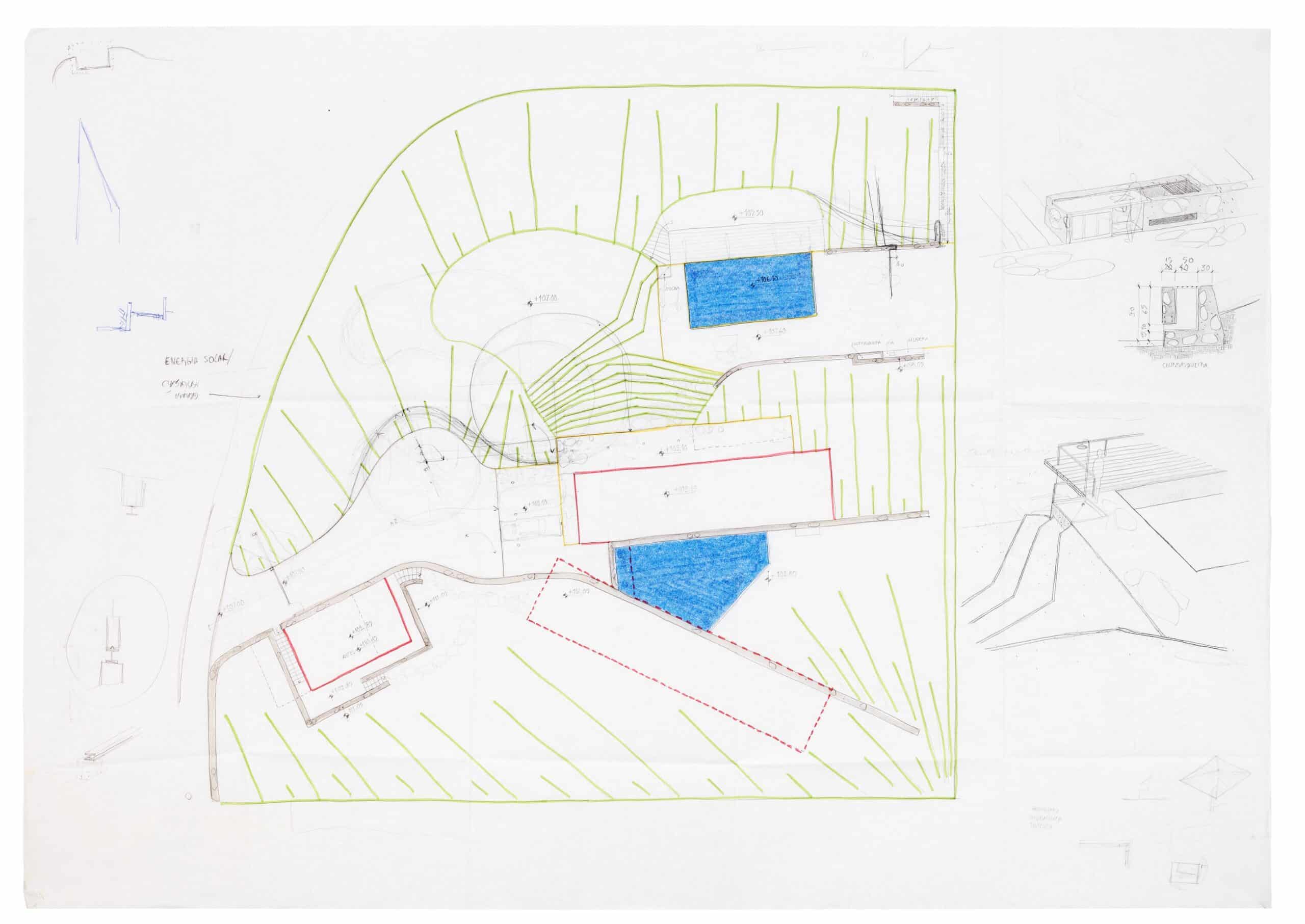

On the edge of a plateau, near the top of a hill, perches the Boa Vista Farmhouse (2008). This house was designed by Marcelo Ferraz for his family in the rural town of Dom Viçoso. Out of the podium-shaped stone base, the building dashes toward a steep slope. Below, as far as the eye can see, successions of plains form the great hills of the Mantiqueira Mountain Range in the Southeastern region of Minas Gerais, near the borders of the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The house – two units in the shape of rectangular cuboids, connected and aligned by a small glass passageway – is arranged longitudinally in relation to the hillside. The ambiance of the blocks, where the common social areas and the bedrooms are set, reveal the magnificent landscape, and in turn, the reason for choosing this site. [6]

The stone base, the whitewashed walls, the wood-fire stove, the veranda looking out to the hill below and the porch looking inward, the two small and narrow rectangular windows (in the kitchen and at the end of the bedroom hallway), the view of the busy fields below, the grassy yard that gives access to the house, the stone wall that establishes the property’s boundaries, the succession of stonework erections built with native rocks, the intimate relationship between the main house and the warehouses for coffee processing and storage, the yards for drying the grains, the homely vegetation resembling untamed undergrowth, which springs up and takes over the exterior upper side of the two functional blocks – in short, the supreme simplicity of the work – all suggest the incorporation of local rural elements into architectural and landscaping projects. [7] This initial impression is acknowledged by the architect himself: ‘when in brickwork, they usually sit on basis of stone.’ [8]

However, the assertion Ferraz makes about the provincial household puts into question the choice made by both architects for summits. According to his book: ‘the most adequate place to build a house and the essential surrounding equipment for daily life’ is, generally, ‘at the intermediate level, half-slope, protected from strong winds, near running water, which should be delivered by gravity’s work, and also on solid ground, without risk of erosion. The construction of the house must never bring about earthworks. Its establishment should be more of a landing, the terrain should be respected in its original contour.’ [9] These are recommendations overtly disregarded in both houses.

The appreciation for the ability to look – the cornerstone of Fanucci and Ferraz’s architectural methods – also moves their designs in the opposite direction of the criteria present in the typical houses of the region, which are dominated by the introspective character of ‘small and closed boxes’. [10] Fanucci sums up the writings of Ferraz on this subject:

‘In this way, the houses seem the ideal shelter, protection, and warmth for those who have spent the entire day working under sun and rain. Home is the moment of intimate regathering, of darkness, permitted by the kerosene lamplight, and respite for the sight, that, from the first rays of the sun until dusk, had its limits set in the blue-green succession of plains that form the great sea of hills.’ [11]

The architects are aware how their projects differ from the region standard. They understand that their own houses are occupied by people who live in the cities, who occasionally visit the premises, and who take in the exuberant views that they permit as precious things in their days of rest. It is completely different from that of the men and women of the country, who are weary of so many hills, so much green, and light, and who would rather rest from work within a house, sheltered from winds, rain, heat, away from the landscape surrounding them. [12]

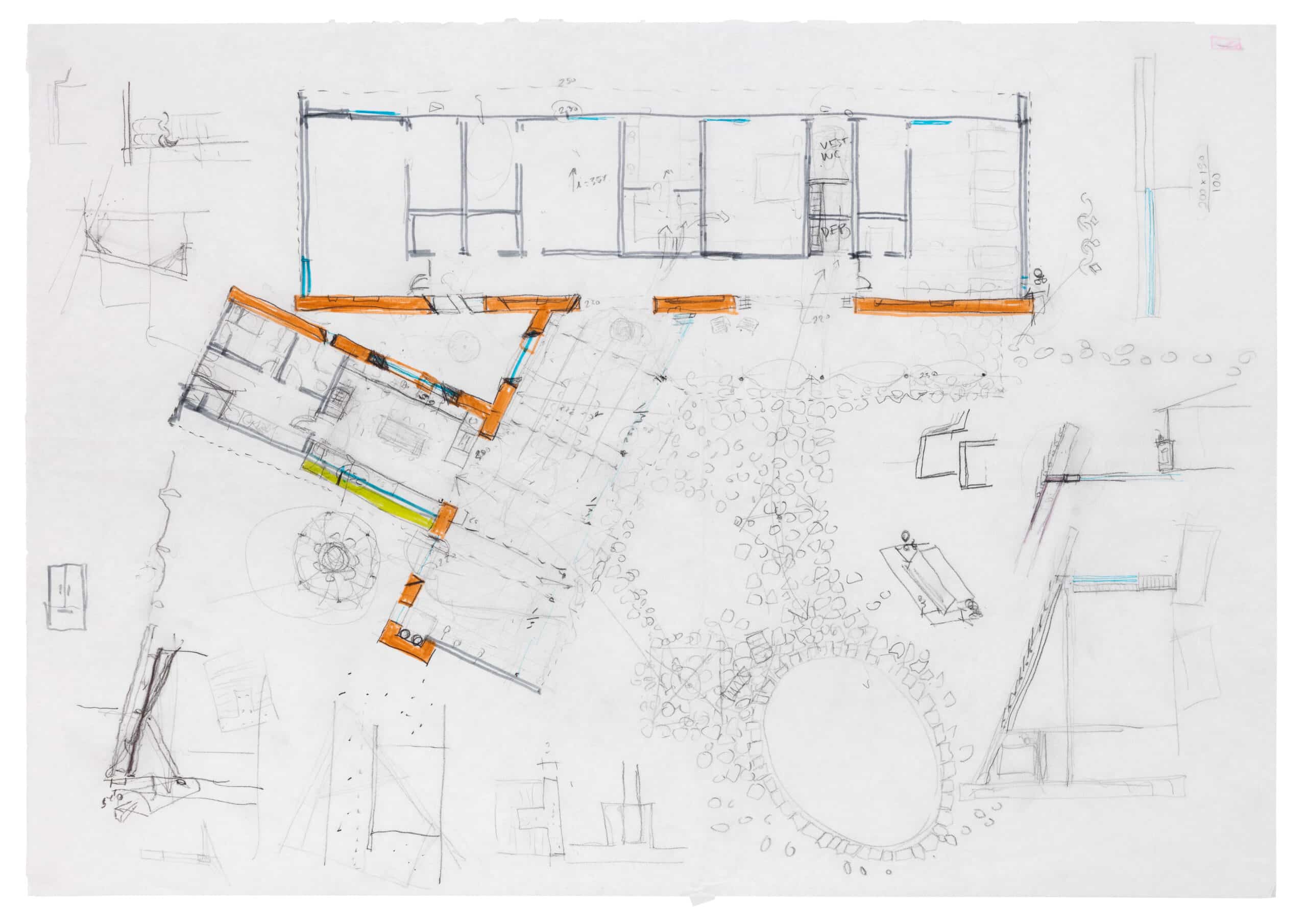

When researching for the Território de Contato exhibition in 2012, Marta Bogéa and I saw the importance both architects placed on their sketchbooks during the development of their projects. In them, there are texts, pictures, and drawings that gather a variety of information regarding the place, the landscape, the terrain, the architecture, the objects, and the local culture as a whole: broad research of regional elements that become direct or indirect references for each project. [13] The research is part of the working process, a phase that precedes the development of project design per se.

Such a procedure is anchored in Brazilian modernist tradition and dates back to the 1920s. In Ensaio Sobre a Música Brasileira, published in 1928, Mário de Andrade asserts that great art has folk culture as a subject and erudite art as an expressive basis. He also raises an alarm not to be misunderstood: ‘if, in fact, now that we are in a formative period, we are to employ often and excessively the direct element provided by folklore, we need not forget that artistic music is not a folk phenomenon, but a development of it.’ [14] The modernist project is, therefore, adapted to our land and our people, as a particular method that prescribes the fusion of native elements and imported procedures.

This guiding principle is verified not only in music – ‘Bachianas Brasileiras’, ‘A Floresta do Amazonas’, and other works by Heitor Villa-Lobos –, but also in the paintings of Tarsila do Amaral and Di Cavalcanti; the literature of Raul Bopp, Oswald de Andrade and the same Mário de Andrade; the architecture of Lúcio Costa; and in the landscaping of Roberto Burle Marx. It is possible to identify in all of them the two aspects foreshadowed by the writer from São Paulo: the initial research of elements from the local tradition (songs, dances, rituals, dress items, household utensils, urban objects, colonial buildings, natural landscapes, native vegetation, etc.), followed by an aesthetic composition or arrangement of modern inclination. A curious unfolding of the method is the so-called ‘ethnographic travels’, which have the purpose of gathering knowledge about national landscapes and culture, a practice that has been adopted by several artists and architects. [15]

The travels and working notebooks of Brasil Arquitetura, like their final projects, are legitimised within this tradition. And, it would be convenient to highlight that the book about the Mantiqueira Mountain Range can be understood as a form of previous research that unfolded not only into the rural home of Marcelo Ferraz but also of his associate Francisco Fanucci, who shares Ferraz’s values and beliefs.

Nevertheless, several project decisions that were adopted (constructive elements, scheduling, spatial arrangement, and typology) align both houses with the cultured tradition of urbanity. The functional division materialised into two sectors, the integration that joins social and service areas in a single space, the relation between interior and exterior, and, most of all, the courtship of minimalist art draw the Mantiqueira House away from local tradition. The flat green roofs that cover both blocks, the bathrooms positioned in the central strip, lighted by zenith openings, the great span present in the quadrature of the integrated living room and kitchen, the single bearing of all portholes in the bedrooms and social areas, the functional division expressed in the bi-nucleated scheme of floor plans, are all indications of the alignment of the Dom Viçoso House to the modernist tradition.

At least in the eyes of Ferraz, the abundance of such elements appears not to be enough to dispel some allusions that greatly bother him. The refusal to construct a more usual roof is justified by the architect as an antidote to the demeaning label of ‘hillbilly architecture’, a label seen by him as a way of ‘quenching certain things, putting a stamp on it and laying it aside’. [16] Attuned to his partner, Fanucci states that his only regret in relation to the decisions made in the project is having opted for a traditional roof, ‘a poor solution for the high grounds of a hill since the wind displaces the tiles’. In line with Ferraz, he affirms point-blank: ‘I would do it differently today; I would use a concrete slab’. [17]

In the text that introduces the houses designed by Brasil Arquitetura in the first book dedicated to the firm, Vasco Caldeira explains the synthesis of the rustic and cultured elements they operate: ‘the residential projects by Brasil Arquitetura have been virtuous sites of experimentation with constructive materials of rustic and semi-artisanal manufacturing, many of them recuperated from Portuguese-Brazilian tradition, many of them modified and adapted; other times, they appear in combination with elements derived from modern erudite culture.’ [18] The elective affinities identified by Caldeira suggest the coupling of two traditions: Modern architecture, with its repertoire, especially the use of reinforced concrete; and vernacular architecture, more tied to the land, concerned with materiality and constructive detail, and drawn to the warmth of living. [19]

Two houses designed by the firm are counterexamples that cause some dissonance from their usual method of formal research. The first one reveals their early education at the University of São Paulo. The second suggests the return of the prodigal sons to the paternal household. The two of them are boxes of three gray opaque sides – the roof and the facades – and two glazed ones, facing the street and the backyard, a recurrent scheme in the São Paulo school. The traditional tripartite division of social area, service area, and bedrooms is accommodated by different designs: Marcelo Ferraz, in a solo project, adopts three middle-levels, with floors built at half-height for his parents’ house (Cambuí, 1979); meanwhile, the Pepiguari House (São Paulo, 2011) establishes itself with a lower social level and an upper private one. [20]

The houses of Ferraz and Fanucci are hybrid objects, a sum of local and foreign constructive elements, a binary opposition that could be translated into ‘folk and cultured’ or ‘autochthonous and exotic’. The incorporation of these elements has two motivations: the first, disciplined and cultural, based on their academic education and intellectual curiosity, a matter already discussed above; the second, perceptive and intuitive, is related to experience and memory.

During our trip together, after initially denying the role memory plays in his projects – ‘there is no place for nostalgia in my work’ –, Ferraz freely began to tell stories about his infancy:

In my childhood, one of the most pleasurable things was bathing in the river where I learned to swim. It was the coolest thing. I would go swimming without telling my mother, but I would dirty myself in the muddy waters and, when I returned, she knew where I had been. Fire was always essential. Every winter, when it was cold in the small town where I lived, there was a bonfire at night. In the abandoned lots beside my childhood home (where the house I designed for my mother is today), my father would light a fire. [21]

Water and fire, natural elements of marked experience in infancy, are very fertile in his residential projects. In both the houses Ferraz designed for himself, they are affirmed; the fire presents itself in its civilized fashion, embedded in the hollowed places of the hearth and the woodstove. The importance of these pieces is emphasised by Ferraz, particularly the significance of the fireplace, present in many of his designed homes and indispensable in his own:

‘I light it even in summer. Sometimes the fire is not for heat; it is like in a village, the fire is there so people will gather around it. The fire inhabits, it creates spaces’. [22] The water element is more present on the outside, on a small artificial lake of running water, which escapes through an outlet placed on the little stone dike.

At Mantiqueira House, there are three spots for fire: the master bedroom, positioned in the extreme section of the private wing, rarely used; the living room, located in one of the extremes of the social wing, used occasionally; and the wood stove, placed on the fold section where kitchen and living room meet, used often, almost always as a hearth. Collective living, eventually, can be extended into the other rooms with soft furniture, or to the porch, protected from sun and rain. From this perfect shelter, one can see or hear external manifestations of nature, its potential violence and vigour diffused through the walls and insulation. The sound of running water falling into its stone basin is perceptible at night and lulls the ears of Madalena Ferraz, the architect’s wife, who hears constant buzzing. [23] In its natural state, water is a trigger for another story by the architect. Once upon a time, with the sun already gone for dusk, they all heard, coming from the little waterfall embedded in the river’s grotto, a thundering roar from a mountain lion that descends from the hills on misty days… [24]

Considering their partnership has lasted for four decades, it is only in their own homes, when there’s relative autonomy for decision-making, that it’s possible to detect each architect’s idiosyncrasies. However, in some measure, the comparison between these projects ends up confirming what the duo share. The Mantiqueira House, by Fanucci, was built almost a decade before the Dom Viçoso House, and a few years after the book on the Mantiqueira Mountain Range written by Ferraz, which can be understood as a kind of programme-letter for both projects. Therefore, understanding the proximities and particularities in the predilections of the architects is not simple. Due to the entanglement of their experiences over time, it is not surprising that several statements regarding project decisions and architectural works of reference are practically the same. This is a symptom of their communal polishing of images, ideas, and values; as gravel is gradually polished by flowing water.

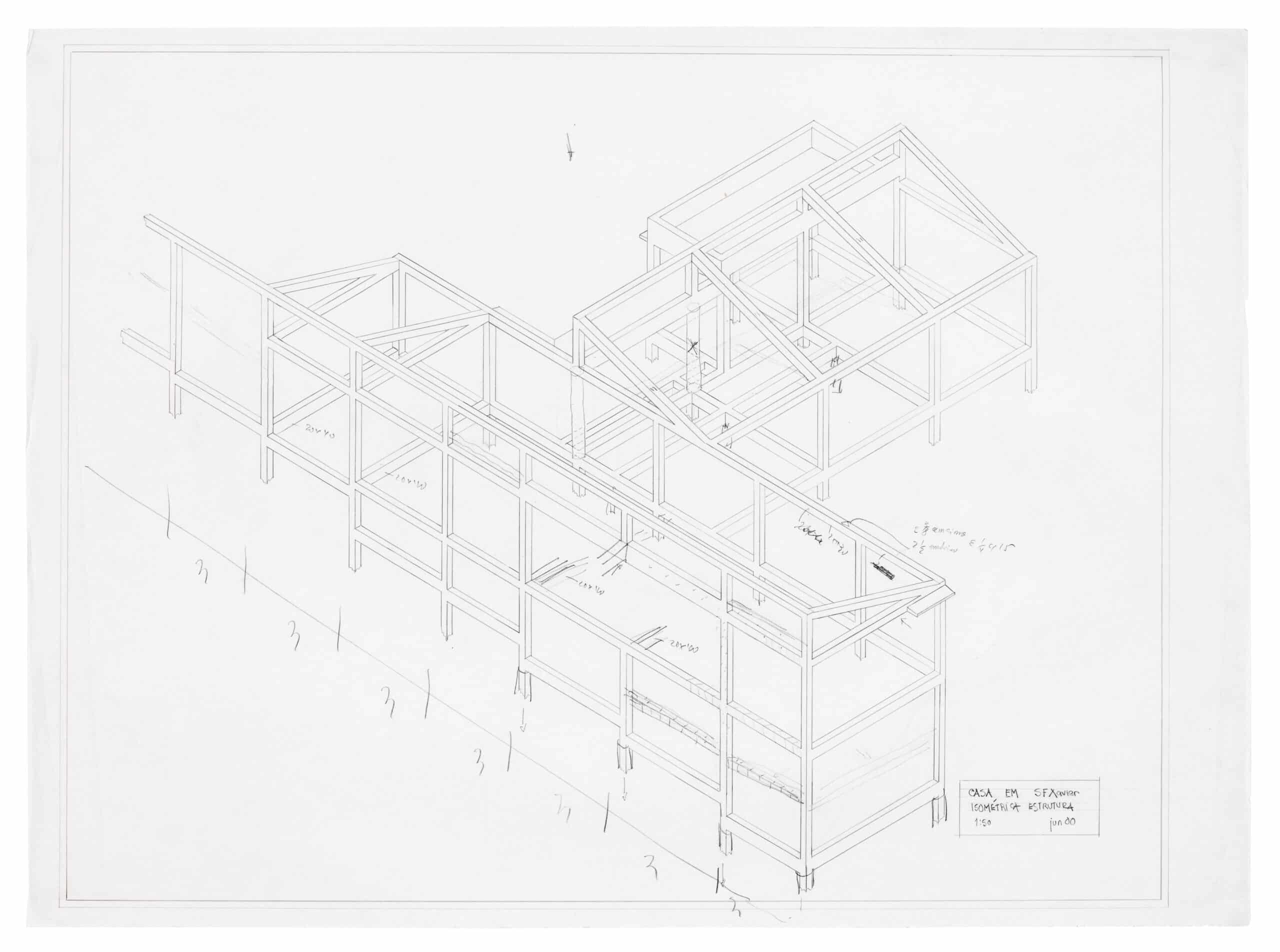

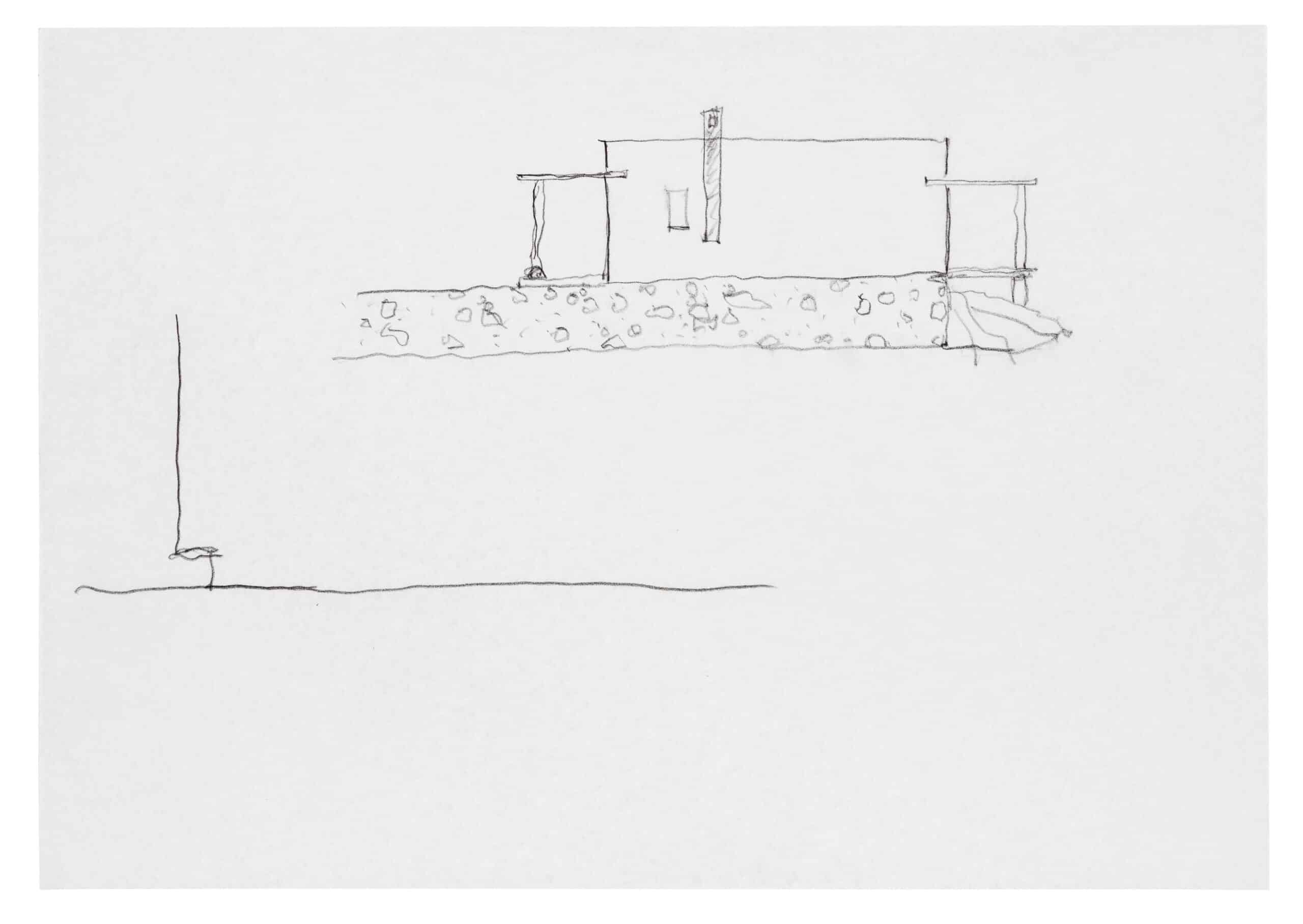

Beyond the aspects already discussed, other elements of communication are visible among the two rural projects, such as the tree trunks serving as pillars. In the Dom Viçoso House, a series of trunks support the porch roof. In the Mantiqueira House, a solitary piece of wood holds up two concrete beams. These are choices that point to a shared repertoire of solutions, where one architect’s original design is developed by the other’s contribution, a common feature in the work of people who share a business for such a long time. According to Fanucci, ‘the tree trunk idea was, initially, for it to be forked, a trunk that divided itself into two branches, one for each beam’. [25] The idea seems to have its inception in the fabulous ‘trees of steel’ by Lina Bo Bardi and crew, in the Anhangabaú Valley contest of 1981. ‘As ancient tropical trees’, the columns fulfil a fundamental task: ‘to give the iron/steel the ingenuous and asymmetrical freedom of nature, set against the regular abstractive scheme of the building’. [26] Gathering roots, belonging to the soil, and by developing natural forces organically, the pillar tree resists artificial human habitat.

The decisions on how to obtain natural light in the interior of these constructions point out flagrant differences between the two houses. Ferraz finds the sophisticated solution of opening a glass slot between the roof slab and three concrete tabs that cover the veranda and the porch (out of the four largest sides of the two blocks, only the one with the bedrooms is left without this protection and is filled with windows that peer out into the landscape). The slabs are supported internally by reinforced steel bars stuck to the superior side; externally, support is accomplished by tree trunks performing the duties of pillars. The result endorses one of the architect’s predilections: ‘I enjoy light; my house is very bright’. [27] In the Mantiqueira House, the three openings towards the main landscape, along with the other doors and windows designed by Fanucci, allow for a gradual intake of light and diversified interior lighting during the day. In this case, we can also see the architect’s predilections at work: ‘I prefer gradation and variation of light in the internal spaces’. [28]

The distinctive typologies also delineate particular aspects in each house. In the Dom Viçoso House, the two stagnant blocks are connected by a small glass hallway. [29] According to Ferraz, ‘you exit in order to enter, it is so much so that the floor of this passageway is gravel. It is quite beautiful when there’s a storm outside and you walk through the rain without getting wet. You cross the stone floor and, then, you are inside again, in another room, with wooden floors. It is a transitory element, a threshold’. [30] The passageway, or vestibule, has the psychological function of rooting the resident in their dwelling. The roughness of the floor and the unobstructed view of the natural landscape simulate being outside during the brief stay in the threshold. The glass and the cover of the hall protect the passer-by from the external elements – therefore, the impact is not on the body, but on the spirit, which is startled by the natural forces, only to be appeased, subsequently, by the certainty of being indoors, protected, nestled. To shelter is to comfort the body and the spirit.

At Fanucci’s house, right on the fold between the two sections, internally, one finds the kitchen with its wood stove; a vital spot, where people gather to cook meals, eat, drink, talk, and fraternise. [31] Gaston Bachelard warns us that ‘every corner of a house, every angle of a room, every narrow space where we like to hide and confabulate with ourselves is, for the imagination, solitude, that is, the embryo of a room, the embryo of a house’. [32] This is a place of immovability, of extreme refuge, the primordial home that lulls our dreams and reveries. Positioned precisely in this crucial corner of the residency, the secondary kitchen door, which opens out into the service area, becomes the primary entrance. According to Fanucci, this was a mistake in the project, resulting from the inability to foresee the space’s importance. [33]

The houses of Ferraz and Fanucci suggest the primordial shelter of our ancestors in the face of an incomprehensible nature. The house is an invention that separates us from nature, it holds within its walls artificial fire, which, in turn, humanises our relations, bringing people closer together. According to Bachelard, ‘this condensed heat, this warm well-being, so loved by men, makes the image jump from the level of the image one sees to the level of the image one lives’. [34] And the phenomenon of being there, we can identify as the deepest root of architecture, its psychological basis, revealed to us in the desires for refuge, comfort, and intimacy.

Still, the particular historic representations portrayed here are products of specific constructive and artistic imaginations, as we have attempted to show. The green roof, now covered with bushes, is an element of great relevance in the Dom Viçoso House. In the Mantiqueira House, it is a residual effect, employed over the outside of the bathroom section, latching onto the bedroom corridor. [35] The apparent ruggedness of the garden roof softens the strict orthogonality of the white walls and concrete slabs. They seem vernacular, but nothing of the sort can be found in the constructions of the countrymen. This device by the architects suggests the randomness of contamination by ecological forces – something that is commonly verified in ruins –, or a shrewd camouflage of the natural habitat, as with animal homes, especially a bird’s nest: ‘our home, understood in its oneiric powers, is a nest in the world’. [36]

According to Bachelard, ‘memory and imagination are not to be disassociated. One and the other work in their mutual deepening. One and the other constitute, in the order of values, the communion of remembrance and image’. [37] In the subject-matter, memory and imagination are usually seen as distinct, working on different registries. If it is certain that collective and individual memories are storages supplied with images and experiences vital for creation, they do not seem to constitute a satisfying answer to justify poetic imagination. In art, it is always possible to verify innovation, something that has not yet been experienced.

Strong images result from the connection between memory and imagination, taken here as embryonic for artistic creation. [38] Full of significance and multiple contents, this connection often escapes the understanding of the artists themselves. According to Fanucci, ‘in the act of designing there is much we do without being mindful of what is done’. In other words, ‘to perform architecture is, in a sense, to take this great leap in an unknown territory, almost intangible, between thought and action’. [39] This risk, divination, or gamble, Fanucci calls intuition: ‘you don’t always have perfectly logical reasoning for it, you don’t always have a technical basis to justify your proposal, but you know that something good might come out of that. It is the time to gamble. And, here, we have a point of contact with the work of an artist, for it is intuition we are talking about’. [40] To follow one’s intuition is to allow oneself to discover solutions that fuse expression and content in unprecedented fashion, it is to transform a strong idea into an invention, it is to give form to poetics. [41]

What we might call the poetics of Brasil Arquitetura nearly always involves a propensity to reconcile architectures of distinct character: a vernacular, organic, tectonic architecture, largely ingrained in the territory; and another architecture, a more orthogonal and geometric one, more functional, abstract, artificial, and typological. To give examples, it is about joining Vilanova Artigas and Lina Bo Bardi; Carlos Millan and Sverre Fehn; or Marcel Breuer and Lúcio Costa, as it seems to occur in the Dom Viçoso House, bi-nucleated, with its porch and swinging hammocks. To this poetical ambiguity, are added the memories of childhood and early manhood in Cambuí, imbued with the experience of collective rural memory in the small town of Minas Gerais.

In the aesthetic creation, elements and typologies of two universes are combined: wood stove and reinforced concrete, porches and functional division. Yet, it would be restrictive to base the understanding of the work on such an obvious foundation. Poetic imagination summons deep spiritual energies and overflows the limits of the objective arrangement of these looted elements. In close observation, the feeling of experiencing relevant aesthetical creation is not absent. The architects explore the potency of strong concepts like the dividing wall, pillar tree, roof garden, passageway, and fold. The essentiality of the house reveals how the phenomenological experience of life is a result of artistic creation – in this case, architectural creation. This final statement by Marcelo Ferraz is of equal simplicity: ‘to build a home is to enter in the experiment of habitat, that first habitat, of the family nucleus. It’s a full project: It’s the place where you live, the place where you eat, the place where you study, the place where you suffer. You give existence to a place.’ [42]

Notes

- The lyrics were sung by Marcelo Ferraz during one of our interviews. © Gege Edições / Preta Music (Eua & Canadá).

- Francisco Fanucci was my host when I stayed in the Mantiqueira House in September 2019. In my comings and goings, we talked about the house and his thoughts on architecture. These conversations were not fully recorded, only notes were made. I conducted a recorded interview with Fanucci in mid-August.

- During our visit, when we were peering out of the kitchen window, an unexpected memory emerged: Fanucci recalled his childhood home in Cambuí, with a window view of the landscape in the background. Francisco Fanucci, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 22nd September 2019.

- In residential projects, the wall is present in the Villa Isabella project through the use of dry-stacked rough stones, trespassed by passageways and vistas. It is also present in the Montemor House; the Tacaruna Cultural Center; the International Olympic Committee; and in the Fachinetto Pottery Museum.

- I am refering to the sculpture Pulitzer Piece, stepped elevation, St. Loius, Missouri, 1971. See: Francisco Fanucci and Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, Francisco Fanucci, Marcelo Ferraz: Brasil Arquitetura, p.160.

- Accompanied by Marcelo Ferraz and our wives, Silvana Romano Santos and Isa Grinspum, I stayed at the Dom Viçoso House for a few days in July 2019. Four interviews were recorded with the architect during this time.

- It is the development of a technique for the enhancement of concrete resistance through water treatment that is typical of architecture in São Paulo. After the first three hours of treatment, the solid concrete slab is covered for a month with a layer of water of 10 to 15 centimeters high, which seeps into the protrusions, becoming a waterproofing factor. Then, the following layers are deposited in sequence: expanded clay to cover the water; geotextile blanket for filtering; sand and dirt, basis for spontaneous vegetation growth. The water level is maintained by an outlet positioned 10 or 15 centimeters high to bleed the water out when it rains a lot; when it does not rain, it serves to prevent complete evaporation, a buoy closes the water outlet to maintain moisture.

- Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, Arquitetura Rural na Serra da Mantiqueira, p.18.

- Ibid., p.18.

- Francisco Fanucci, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 22nd September 2019.

- Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, Arquitetura Rural, p.19.

- In the photographs by Marcelo Ferraz (published in his book about the Mantiqueira Mountain Range), you can see the measured presence of porches, generally small, at times absent, reaffirming the little disposition countrymen have for relating to the surrounding nature in their few hours of respite.

- Marta Bogéa and Abilio Guerra, ‘Algo muito humano além de belo. Exposição Território de Contato, módulo 1: Cao Guimarães e Brasil Arquitetura’, or ‘Contact Territory’.

- Mário Andrade, Ensaio Sobre a Música Brasileira, p.37.

- Abilio Guerra, ‘Modernistas na Estrada’.

- Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 26th July 2019.

- Francisco Fanucci, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 22nd September 2019.

- Vasco Caldeira, ‘Casa Brasilis’, in: Fanucci and Ferraz, Francisco Fanucci, Marcelo Ferraz, pp.114-115.

- Vasco Caldeira cites many of these cultivated references, including: the Brazilians Lina Bo Bardi, Lúcio Costa, Francisco Bolonha, Alcides da Rocha Miranda, Carlos Ferreira, Vilanova Artigas, Paulo Mendes da Rocha, and Carlos Millan; the Portuguese Fernando Távora and Álvaro Siza; and Alvar Aalto, Sverre Fehn, Luis Barragán, Hassan Faty, Geoffrey Bawa, Le Corbusier, and Marcel Breuer.

- Two institutional projects carried out at dates close to those of the houses adopt similar procedures. The Cambuí City Hall – a project designed by the architects Marcelo Ferraz, Marcelo Suzuki, Jose Sales Costa Filho, and Roman Tâmara – and the Work and Workers Museum are gray cuboids on pilotis with sliced slabs in the intermediate levels of its interior, connected by stairs and bridges. Patricia Nahas attributes this search for synthesis to the double education the architects received. At the School of Architecture and Urbanism – FAU USP they were taught to follow the rigors of the orthogonal concrete box. Later, they were converted to the popular ways by the indirect teachings of Lúcio Costa and the fundamental and direct influence of Lina Bo Bardi. Patricia Viceconti Nahas, Brasil Arquitetura: Memória e Contemporaneidade. Um percurso do Sesc Pompeia ao Museu do Pão (1977-2008).

- Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 26th July 2019.

- Ibid. There are fireplaces and wood stoves at the the Pepiguari House and the house Ferraz designed for his parents. These projects are more in line with São Paulo orthodoxy, but these elements link them to the series of residential projects by the firm.

- Francisco Fanucci, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 17th August 2019.

- Ibid.

- Francisco Fanucci, ‘WhatsApp Message to Abilio Guerra’, 2nd October 2019.

- Lina Bo Bardi, Ucho Carvalho, Francisco Fanucci, Paulo Fecarotta, Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, Bel Paoliello, Guilherme Paoliello, Marcelo Suzuki and André Vainer, ‘Anhangabaú Tobogã – concurso de projetos, São Paulo, 1981’, in: Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, ed., Lina Bo Bardi, p.252. The solution resembles the stylised tree pillars of the Bread Museum, a later project.

- Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 26th July 2019.

- Francisco Fanucci, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 22nd September 2019.

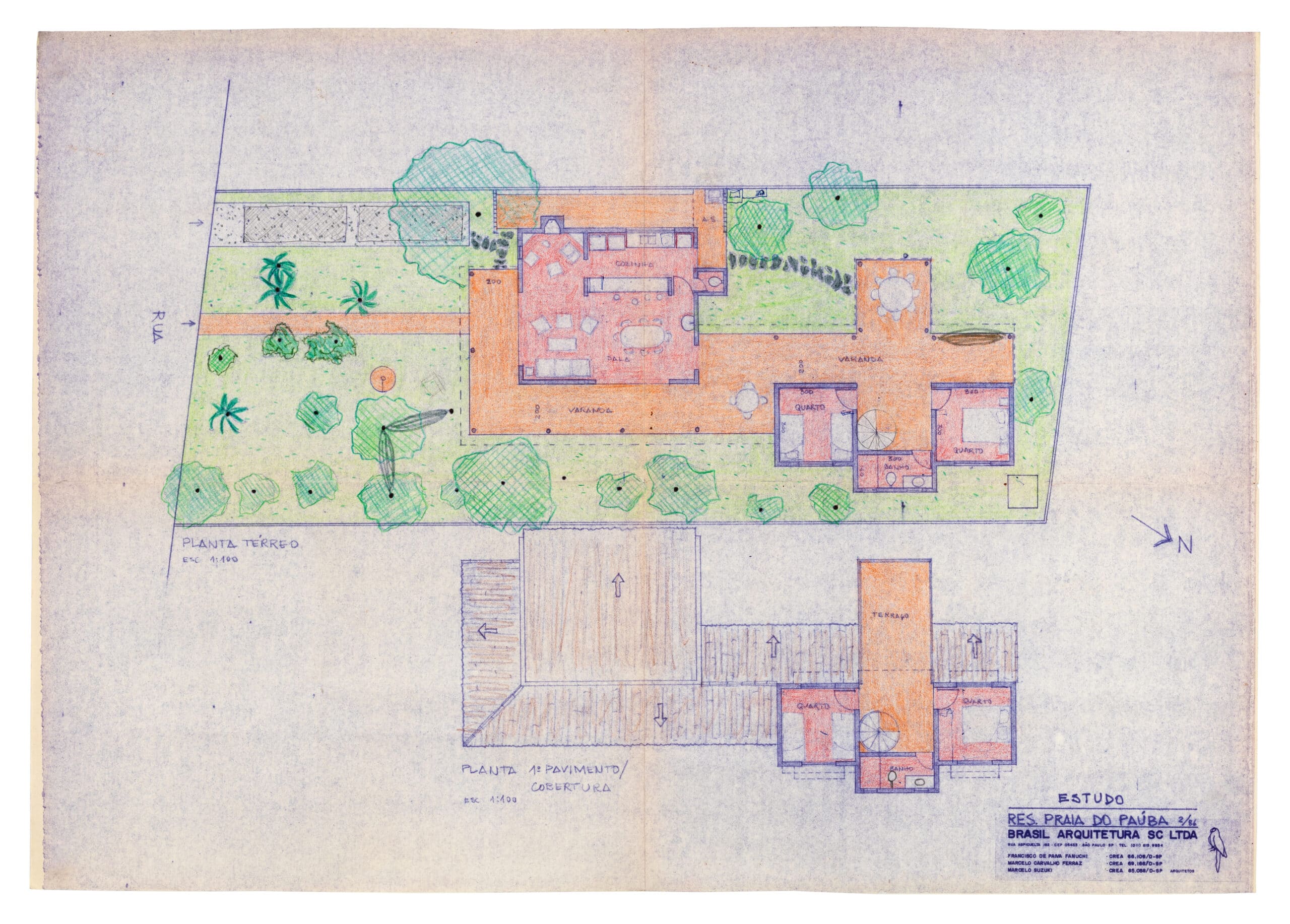

- The insulated glass passageway is used at Tamboré house, Cotia House , Lagoa House, and Villa Isabella. Only with the cover, it appears at Paúba House, Villa Carolina House, the Bread Museum, and the Tacaruna Cultural Center. Uncovered, as a footbridge, it appears at the Rodin Bahia Museum. In the original project for the Ubiracica House, the dining room and the office would be in a glass slab running loose over the water mirror, an idea that was abandoned during construction.

- Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 26th July 2019.

- The fold and the wall were used together in the Muro Azul House to ensure complete isolation of the residence from the neighborhood and to capture the lighting from above, which gives the interior of the house a blue hue. At the Aldeia da Serra House, the building’s division into three functional blocks gives form to two folds when viewed from the outside.

- Gaston Bachelard, A Poética do Espaço, p.286.

- However, one can assume that intuitively he understood that this was the dwelling place to be preserved. He could not imagine that, for those who arrive, to walk in through this entrance would be to walk directly into the home.

- Ibid., p.296.

- The green roof also appears in the Araucária Museum.

- Gaston Bachelard, A Poética do Espaço, p.264.

- Ibid., p.200.

- Something along those lines was said by Fanucci: ‘One does not control memory, it manifests itself many times without our knowledge. Madalena, my wife, made some embroideries with favelas as the theme. The other day, returning to São Paulo, as we passed through Guarulhos, she mentioned that those images of the favela had been recorded in her memory and came to mind, without her realising it, at the time she was designing her embroideries. It had been in her memory, but she only identified the process a posteriori. Of course, there was also her intervention on the image she had in her memory’. Francisco Fanucci, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 22nd September 2019.

- Francisco Fanucci, ‘Interview’, in: Fanucci and Ferraz, Francisco Fanucci, Marcelo Ferraz, p.178.

- Ibid., p.178.

- I sensed the role these ideas played in the works of Brasil Arquitetura suring the thesis advice for Patricia Viceconti Nahas, but it was a decade later that I found the appropriate conceptual basis to formulate it.

- Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, ‘Interview with Abilio Guerra’, 26th July 2019.