Torrentius, or The Visage of Time

Tête-à-tête

Charles Vandenhove’s transformation of the Hôtel Torrentius in Liège’s Rue Saint-Pierre between 1977 and 1981 marked a crucial point in the trajectory of both the building and the architect. When, in November 1977, Vandenhove purchased the mansion to set up his architectural practice and city home, the building was in a critical state. Designed around 1565 by the Liège painter and architect Lambert Lombard for the Christian humanist Laevinus Torrentius, it had undergone numerous alterations by successive owners: in the 18th century, in particular, its large, lofty rooms were reorganised in plan and section, and the façades were significantly recomposed. But it was above all in the 20th century that prolonged neglect deeply affected the building. Despite its classification in October 1969 as historical monument, the historian Pierre Colman described the state of the building as ‘approaching a point of no return’.[1]

Approaching the age of 50, Vandenhove saw his architectural career falter. Following political changes, he lost his main patrons at the University of Liège, an institution that had been his primary sponsor in the previous two decades, and for which he had delivered a highly coherent series of buildings with powerful architecture and raw materiality, echoing the contemporary works of Louis Kahn, Aldo van Eyck, Alvar Aalto or Jörn Utzon.[2] Entirely dedicated to public utility, these buildings share an additive, modular mode of composition, linked to a strong construction system. The most ambitious of the series, the University Hospital project, planned for 1,100 beds, suffered severe budget cuts in the mid-1970s, and was a forerunner of the gradual disavowal of the architect by the client, which culminated in his outright dismissal in July 1986, before the project was completed.

At this critical juncture, Vandenhove’s transformation of Torrentius should be understood as a moment of architectural introspection, as a phase of questioning his methods and as the laboratory for a new phase of his architectural work. The project has generally been interpreted by critics as an emblematic example of architects’ renewed interest in the historic city and architectural heritage, in reaction to two decades of urban renewal—particularly destructive in Liège—and the wake of the 1964 Venice Charter. While it certainly is, as Geert Bekaert has rightly observed, the project is ‘in no way an archaeological restoration of a supposedly original state, but a search for what this historic architecture can still offer in the way of answers to today’s architectural and urban planning problems.’[3]

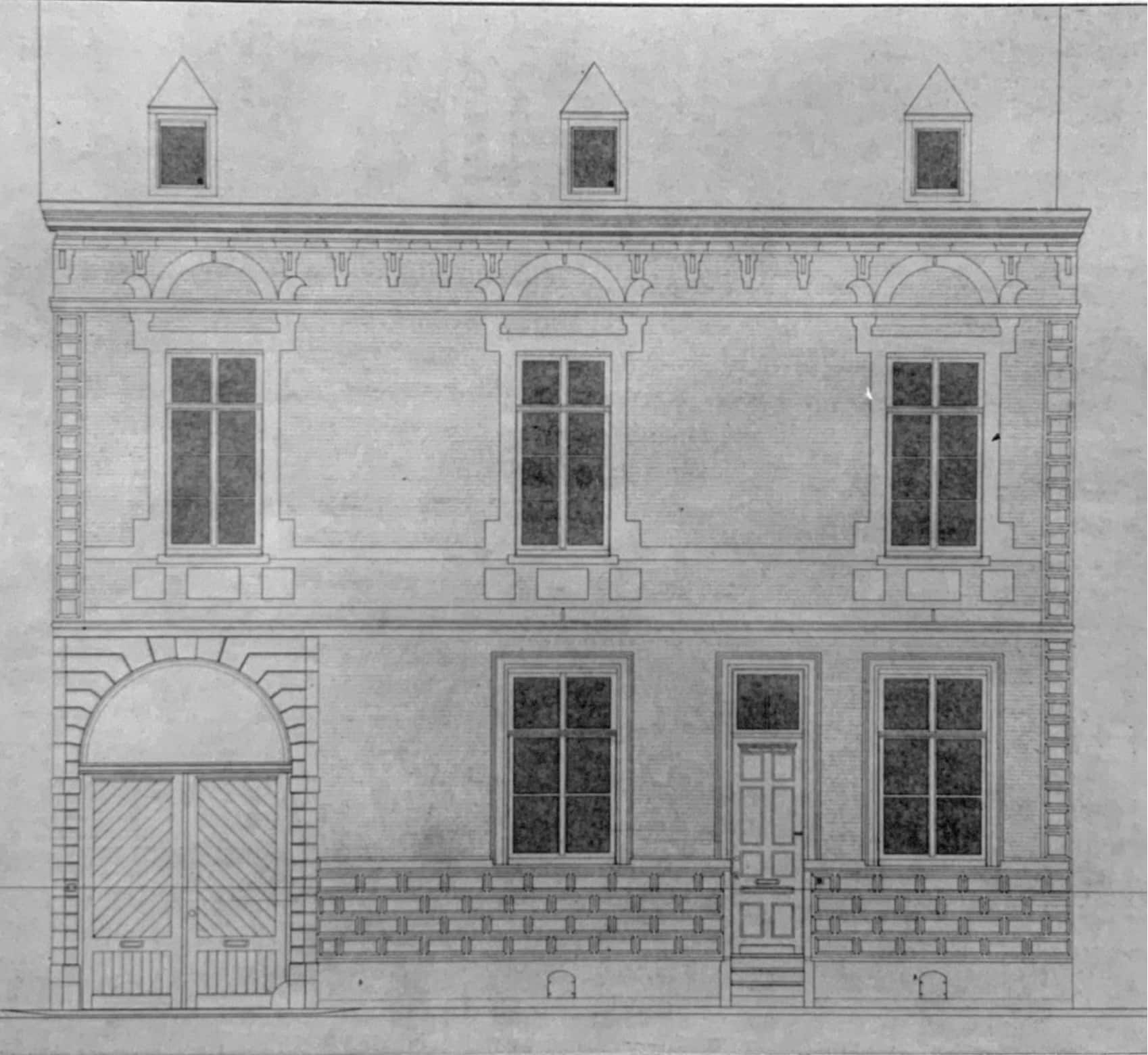

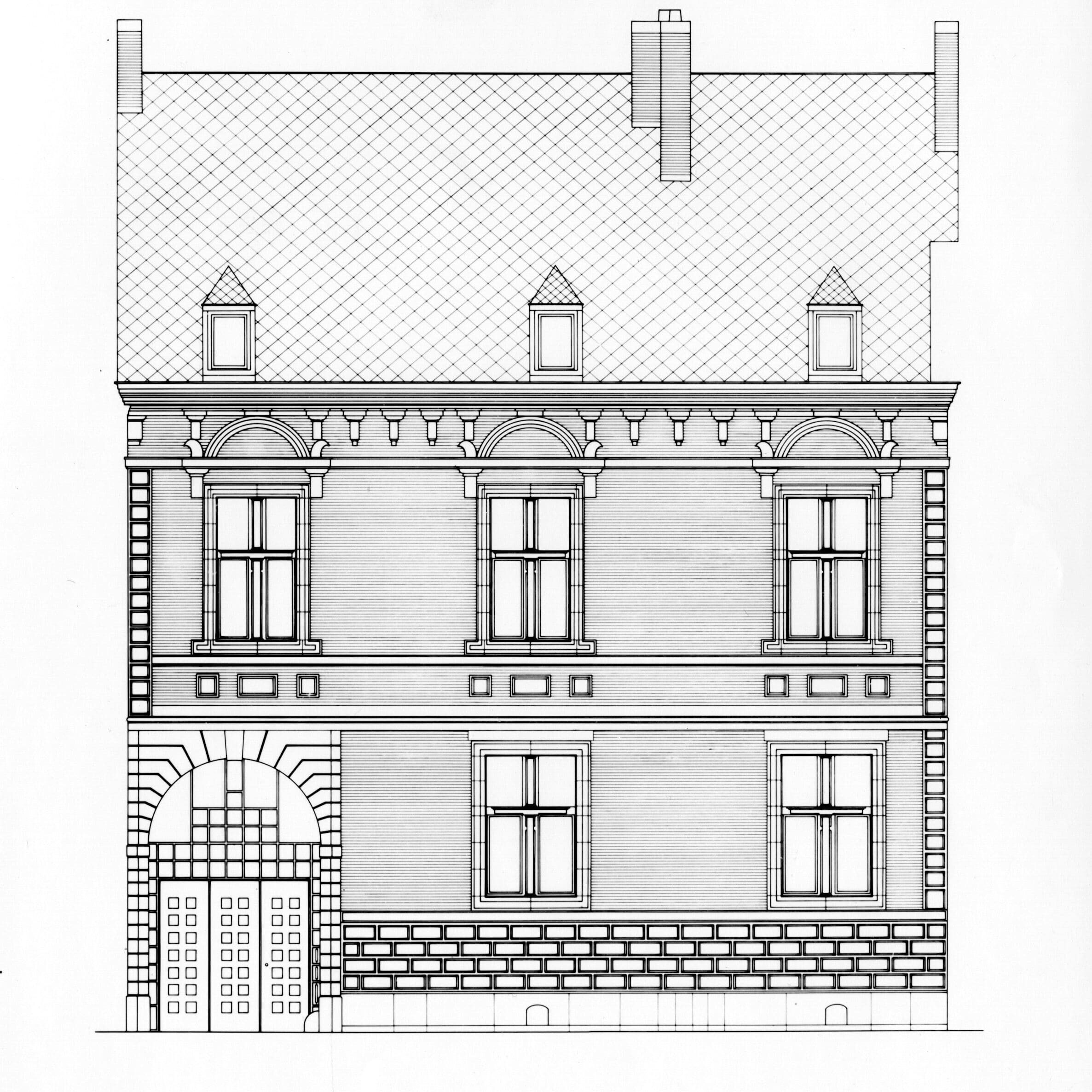

In tense negotiations with the Royal Commission for Monuments and Sites (CRMS), which advocated strict restoration, Vandenhove subjected Torrentius to a kind of conservative surgery, of which he claimed to be the sole judge, and which was accompanied by intense visual production: graphic, photographic and photogrammetric surveys, sketches, research and drawings of countless versions.

While the architect restored some of the principles of Lambert Lombard’s design—the enfilade of rooms, the regularity of the façade—he also ratified certain ‘impure’ 18th-century transformations. In particular, he retained the middle bay of the eastern façade, which had been fitted with an entrance portal and a first-floor balcony, but removed the grand staircase that encumbered one of the rooms. While he reconciled the building with itself, he also added a new architectural stratum of his own making.

Two themes are closely interwoven in the project. The first is temporal: Vandenhove, who had always opposed architecture to the erosive forces of time, sought less to restore the spaces of Torrentius than to reveal and extend its intrinsic temporality. His aim was not to embalm it in a state of historical purity, but to give it new life, to perpetuate its own existence.

The second theme is almost autobiographical. More than an architectural project, Torrentius is the story of an encounter, of a confrontation between architect and architecture, between what each of them carries, one measuring up to the other, as if in a hand-to-hand, a tête-à-tête. Vandenhove ‘identified himself, so to speak, with this architecture.’[4] In this perspective, the question of what form to give to its ‘face’ seems to have been a particular obsession for the architect.

Character

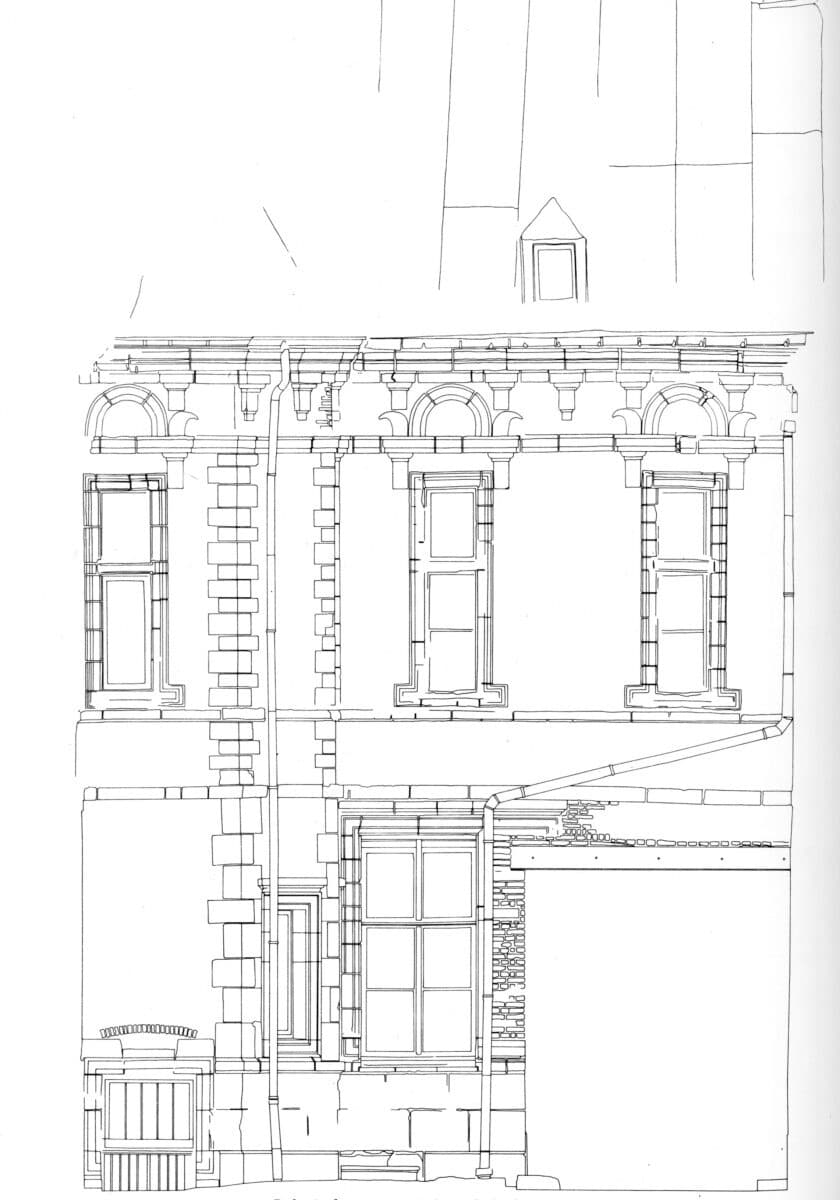

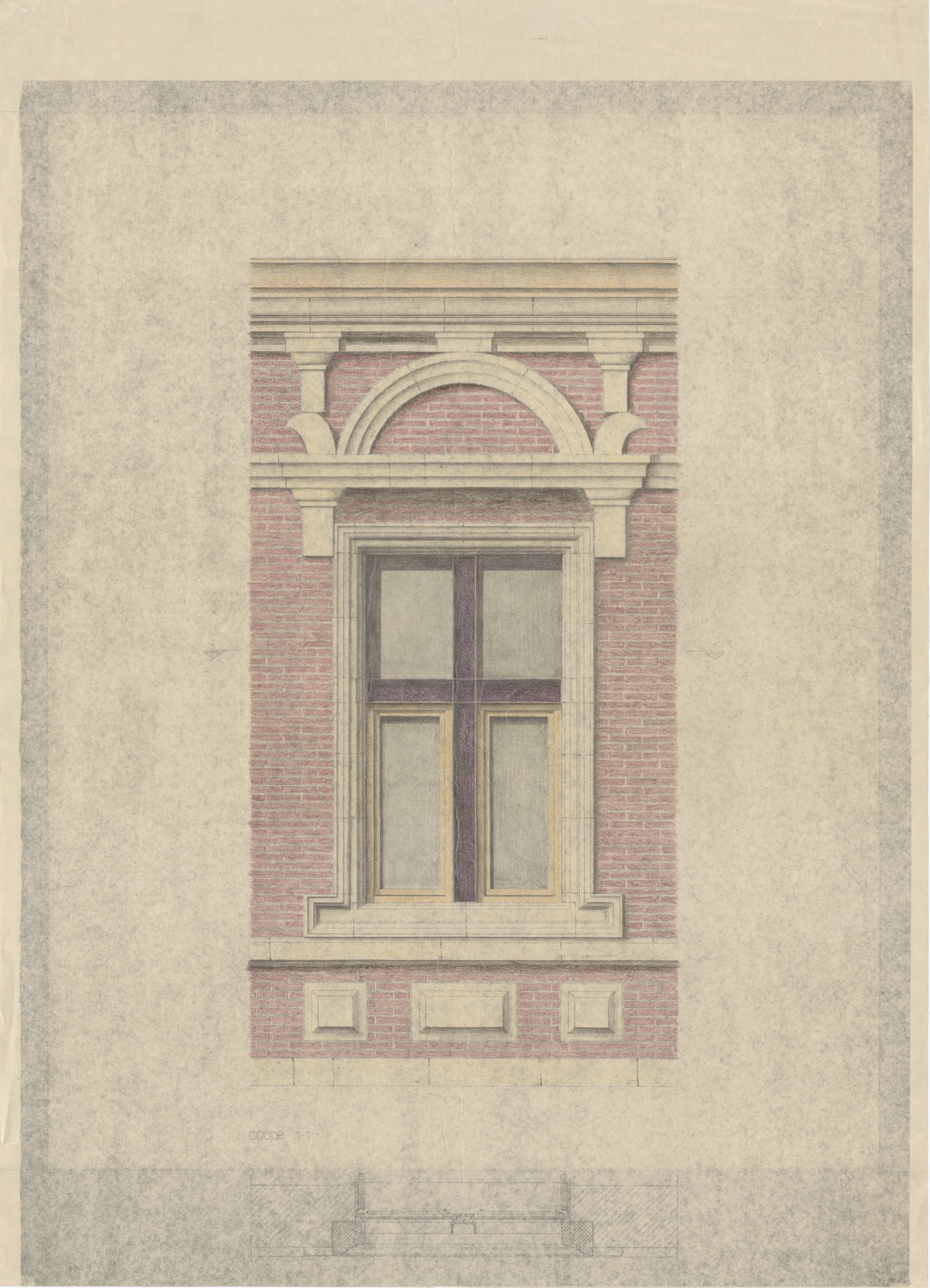

After the first stage of rescue work, which began in autumn 1978 (roofing, structure, etc.), a long period of reflection began, focusing in particular on the façades. One of the lessons Vandenhove drew from Torrentius was the privileged role of window architecture. In the first part of his career, the architect already attached great importance to elements and their composition. But these elements, be they modules, volumes or patterns, had to do with the overall volumetry and were immersed in a certain abstraction. With Torrentius, the element changes its nature, drawing on (and reinterpreting) the classical repertoire, in which the window figures prominently.

© Jeanne and Charles Vandenhove Foundation.

© Jeanne and Charles Vandenhove Foundation.

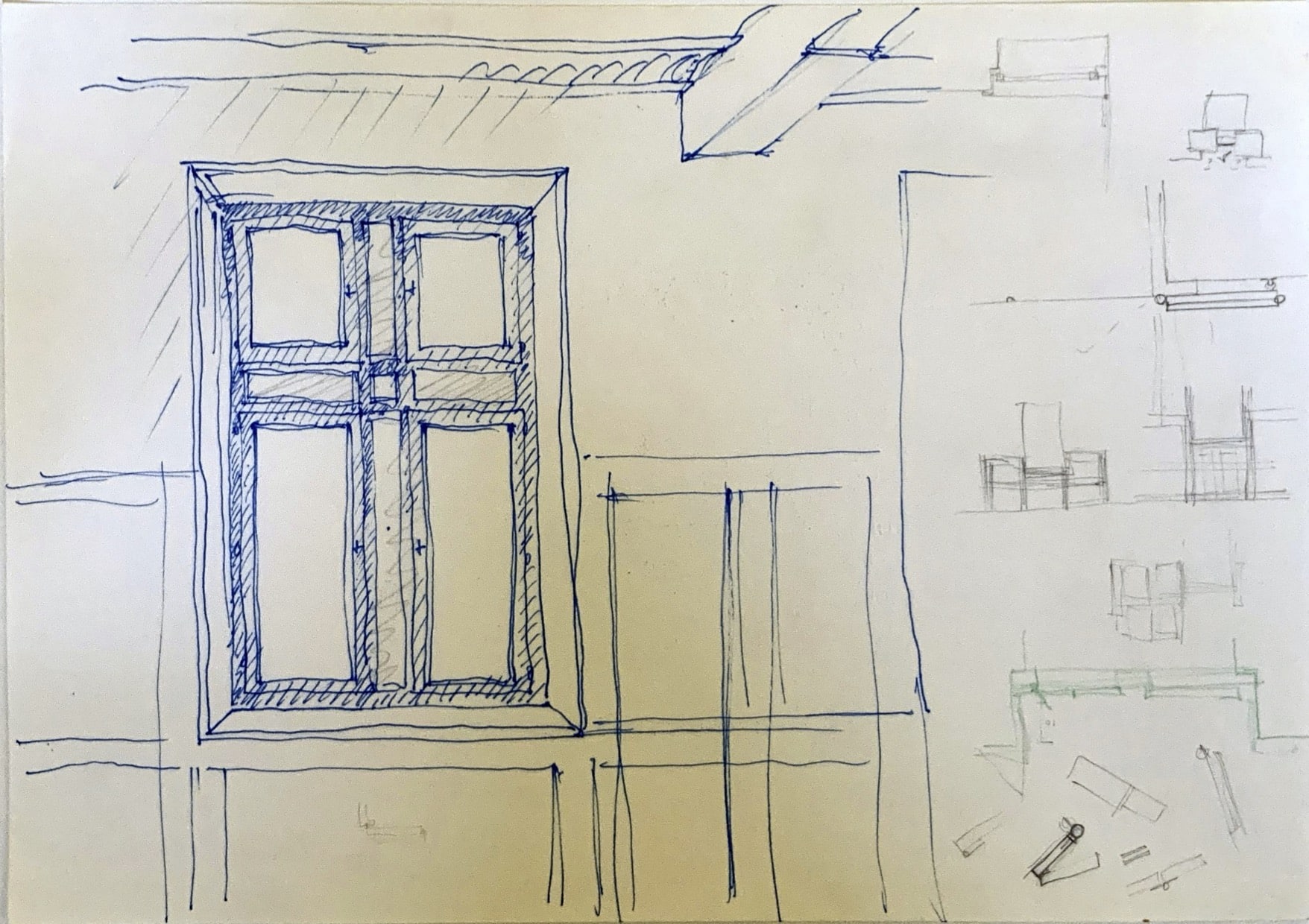

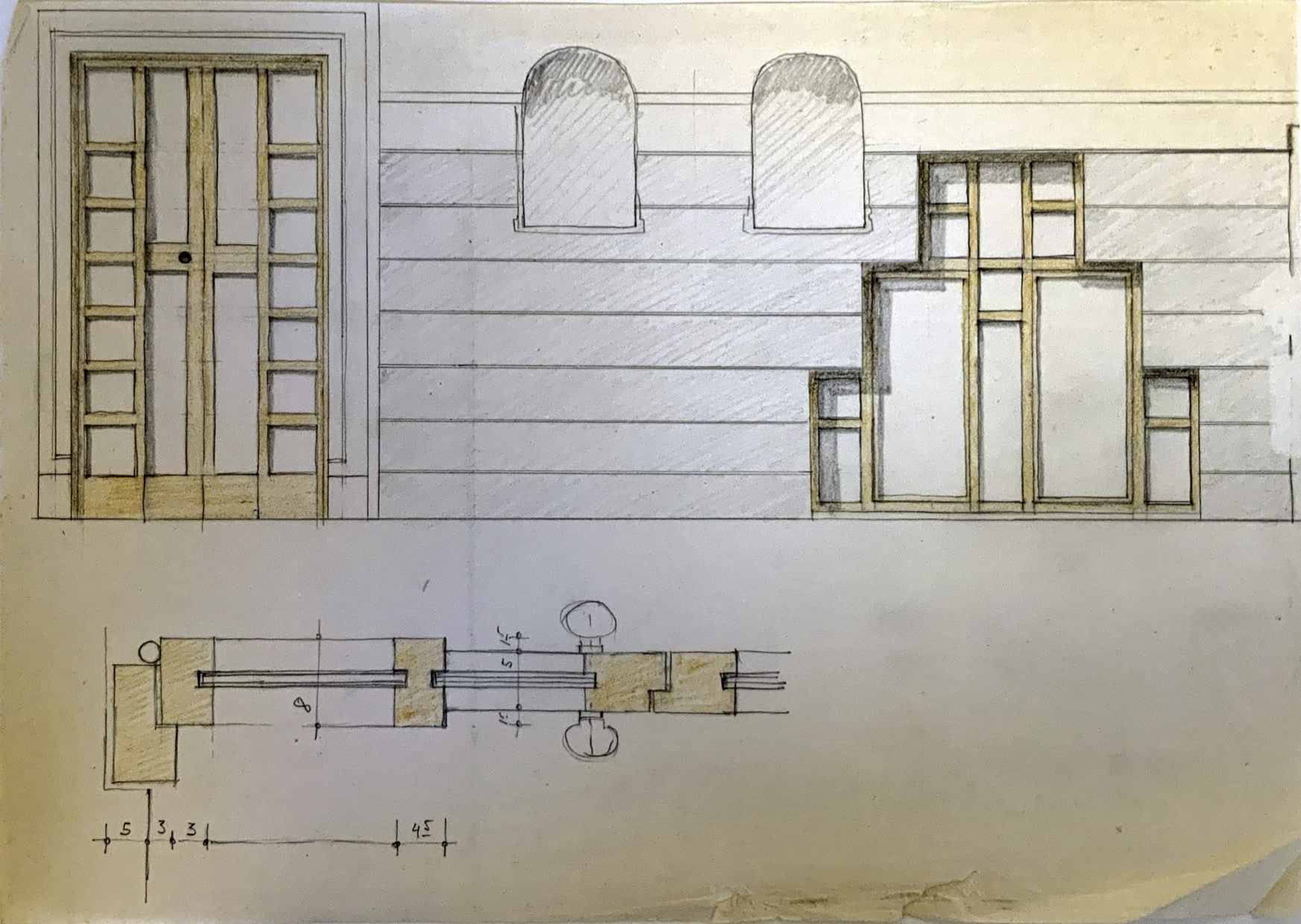

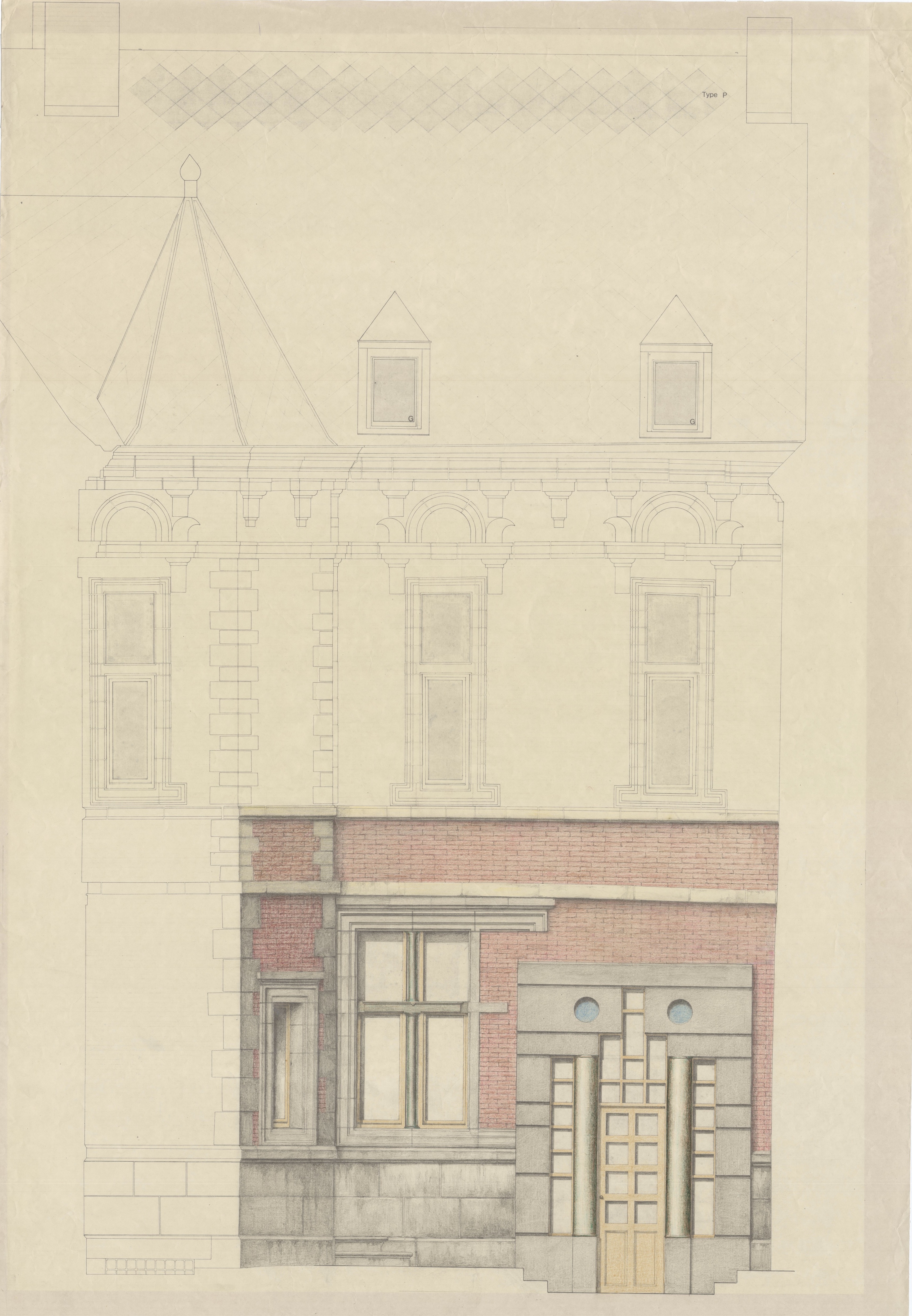

It soon became clear to Vandenhove that the proportions and mouldings of the original openings needed to be restored, which meant filling in later bays and rebuilding parts of the bluestone base, sills, cornices and tufa stone architraves in identical style. However, wherever the stone crosspieces had been removed, the architect decided to reinterpret this Latin cross subdivision using contemporary, and possibly industrial, means, identifying this detail as a key point of his architectural contribution.

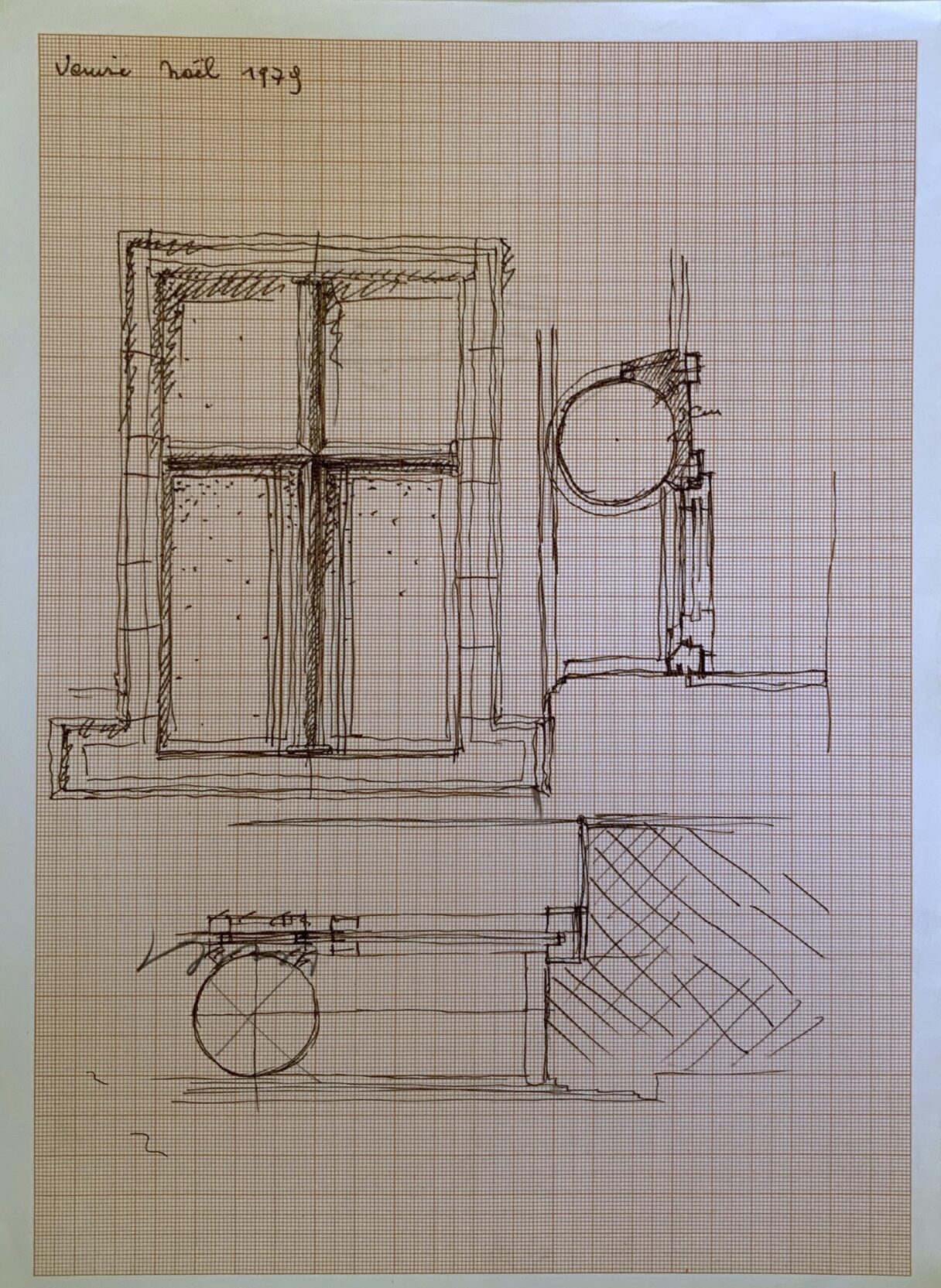

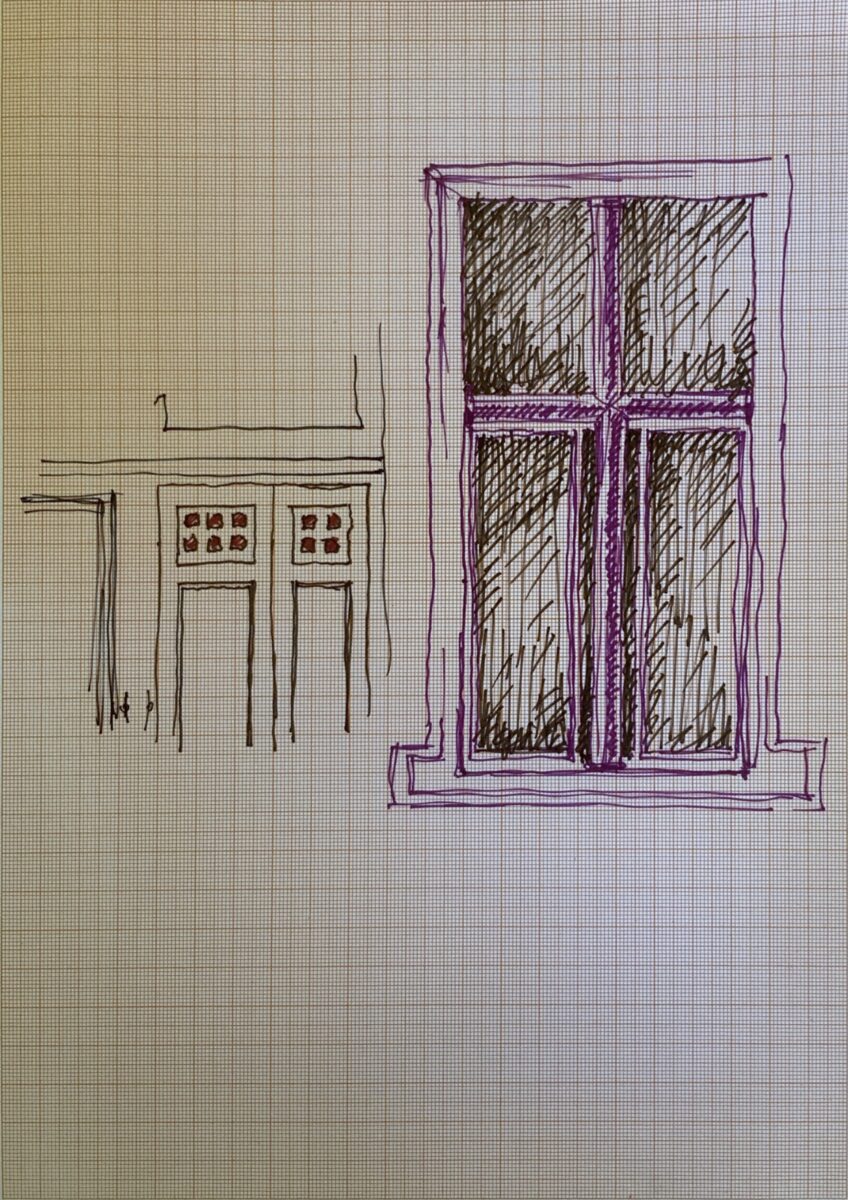

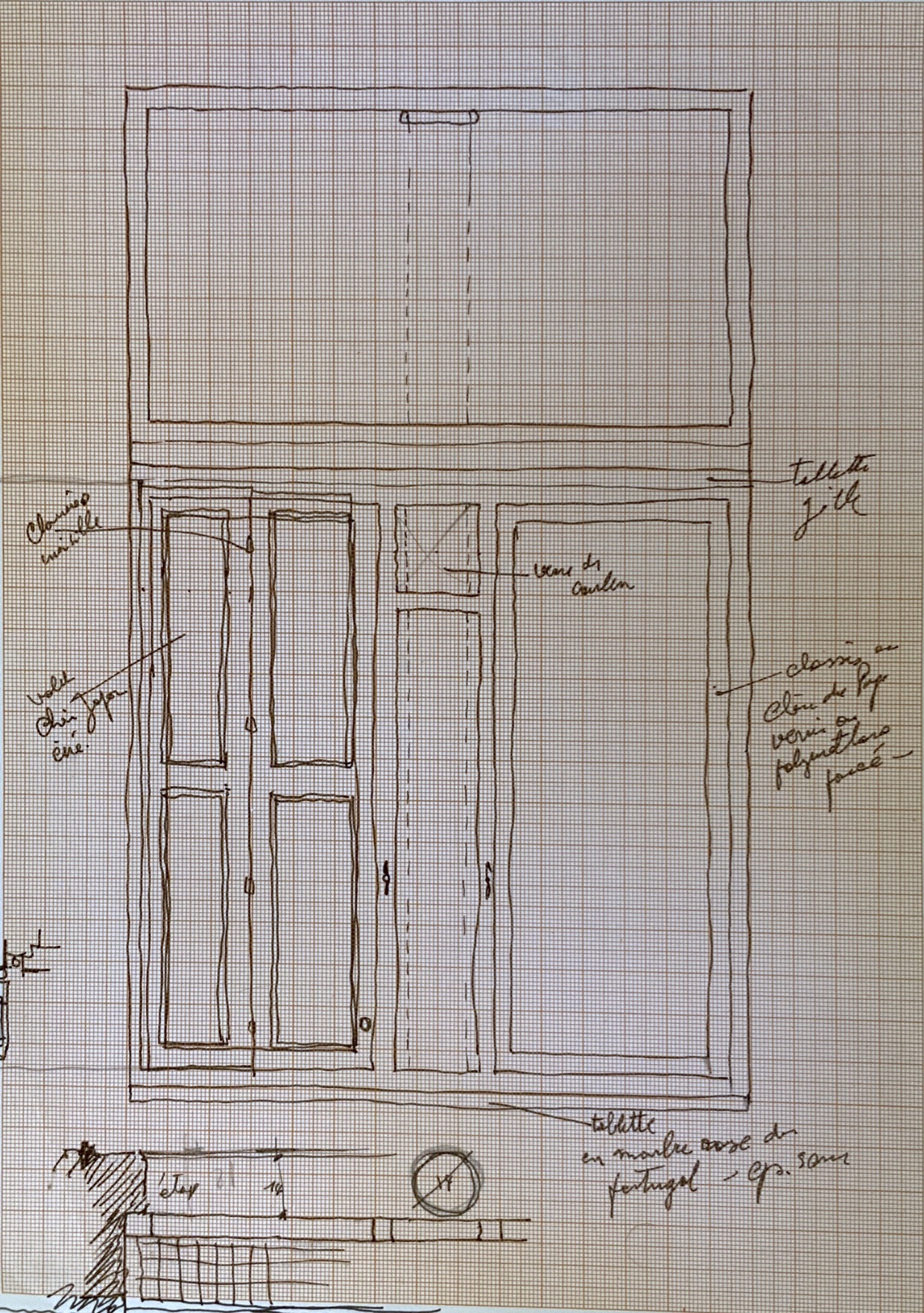

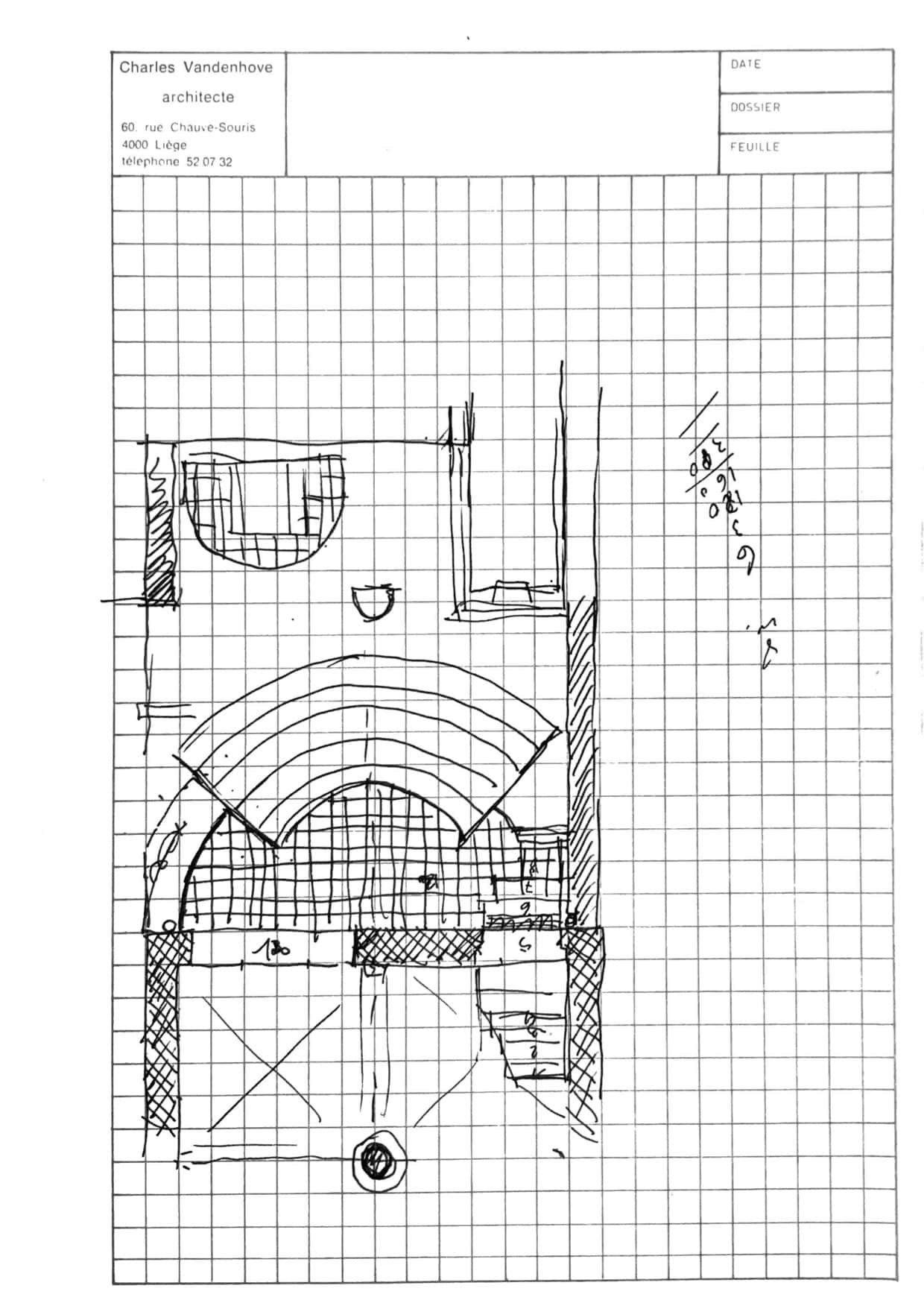

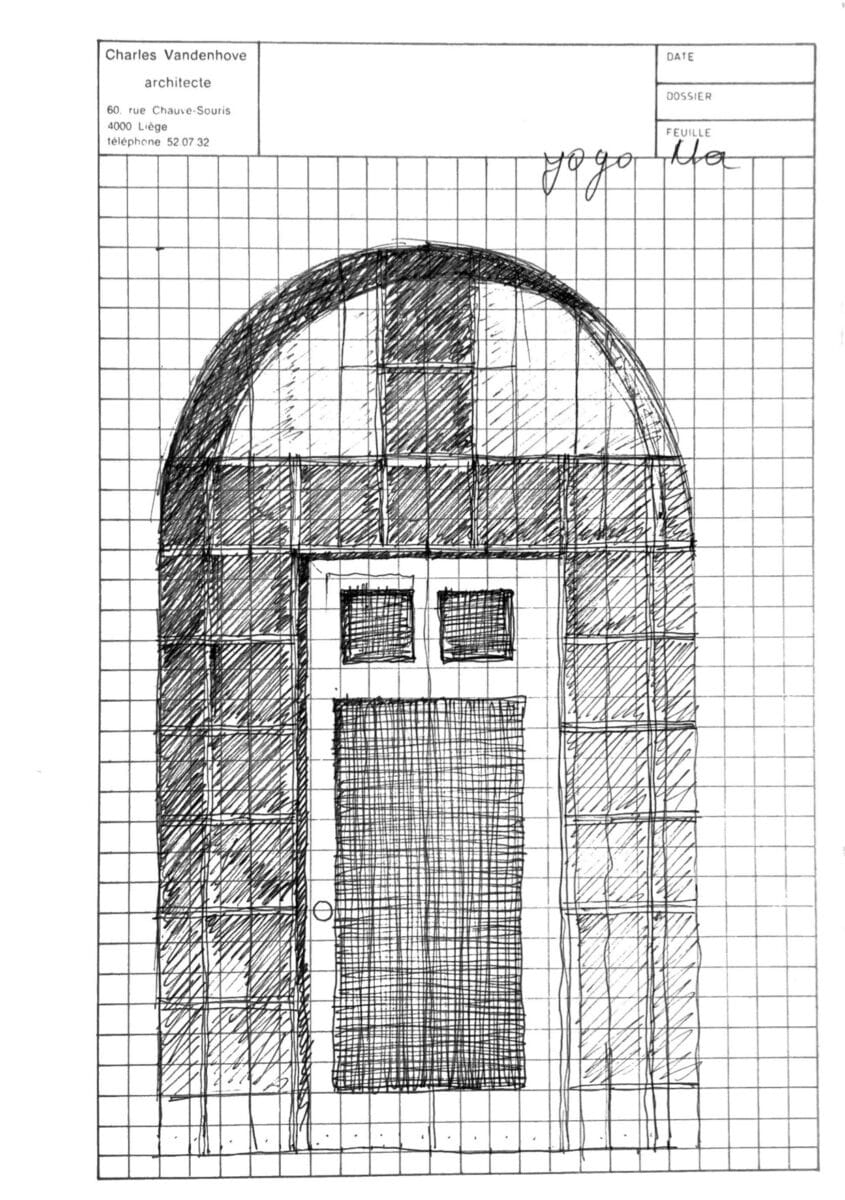

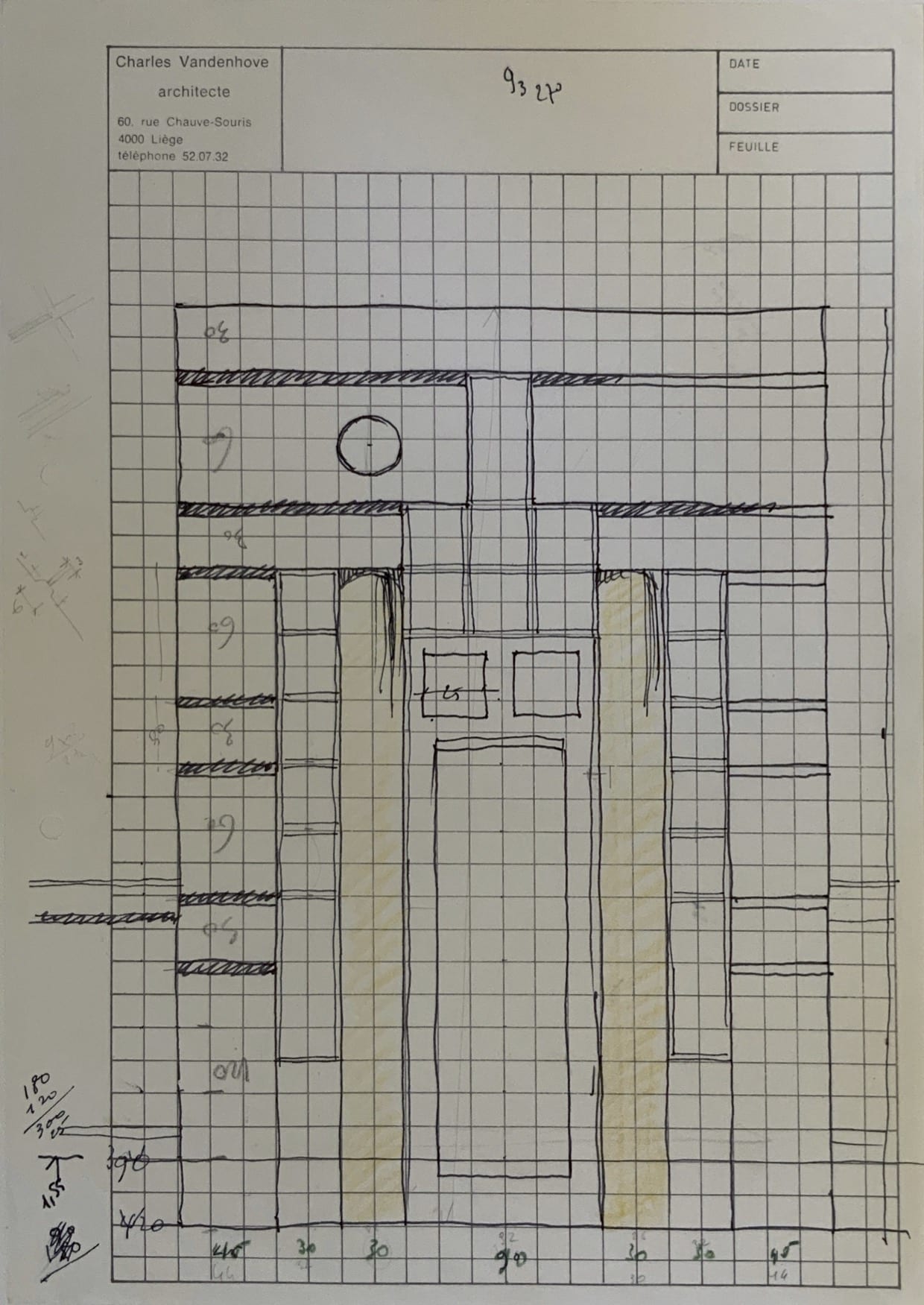

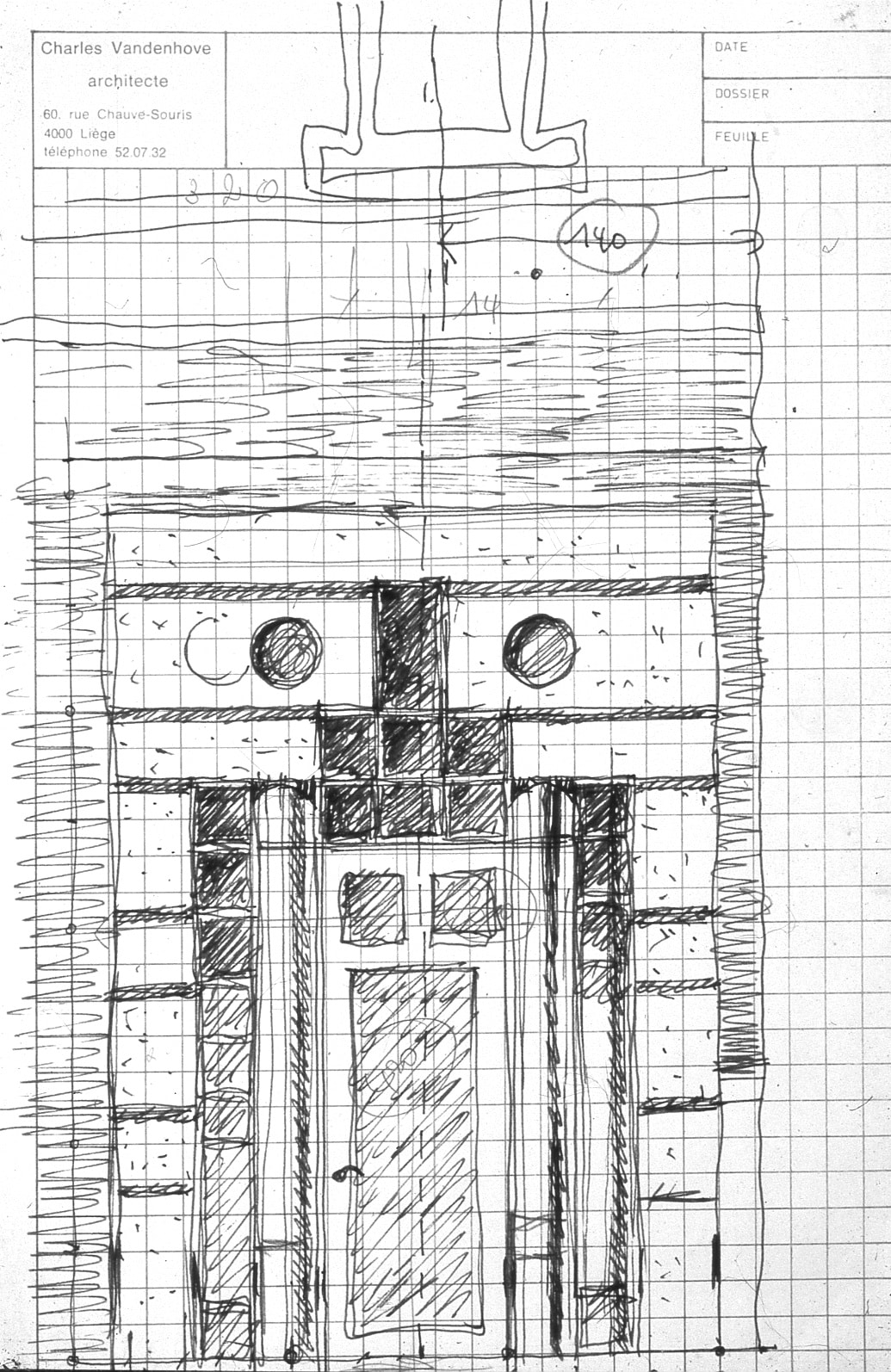

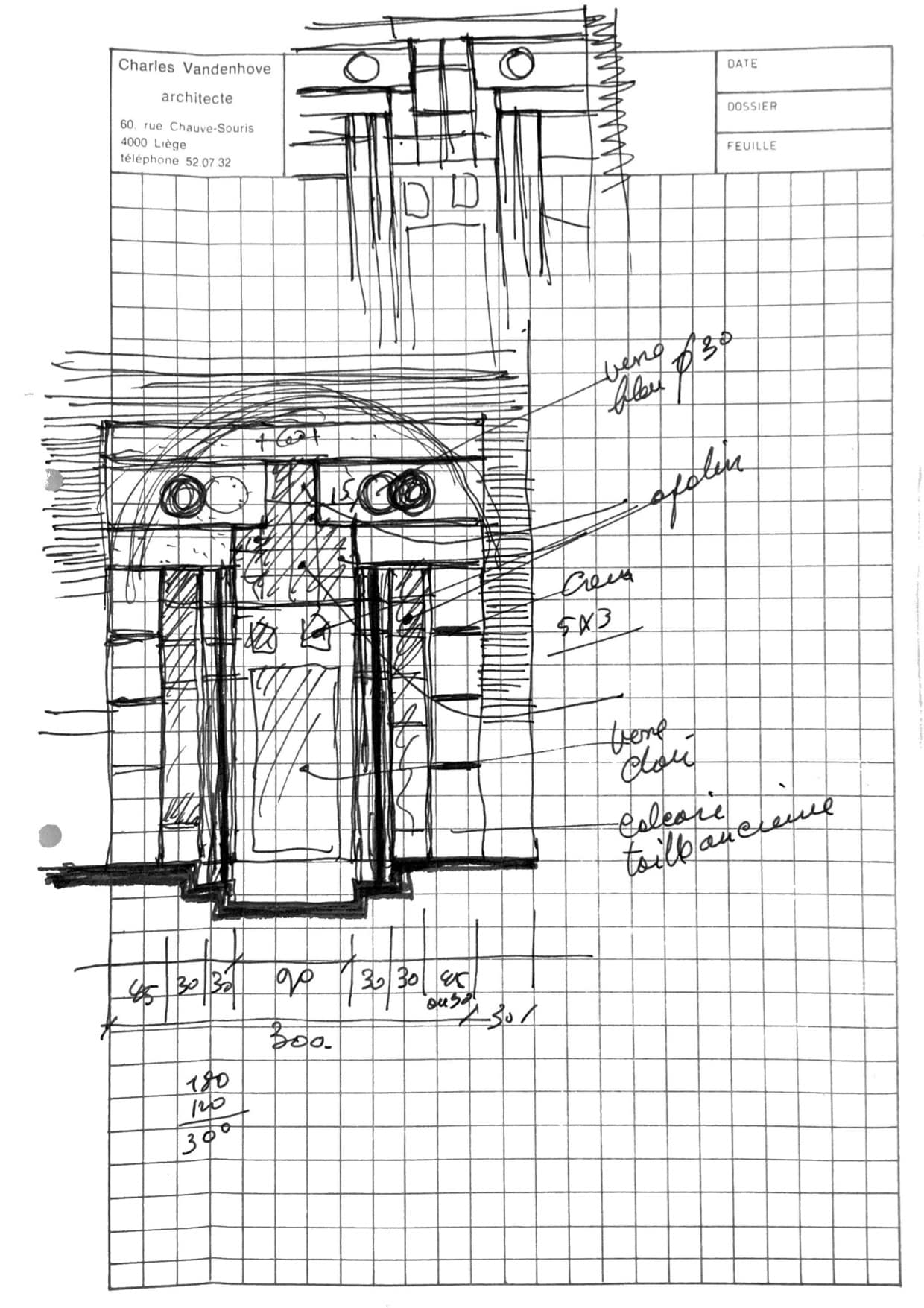

His freehand sketches, sometimes on graph paper, sometimes on squared paper with the firm’s letterhead, bear witness to the intensity of his thinking. During the winter of 1978–1979, a first option took shape: two steel I-beams, perpendicularly welded and lacquered, would form the crosspiece. A rendering drawing, shaded and coloured, was produced by one of the office’s collaborators in May 1979.

A prototype, lined with an oak frame with four sashes, was produced and installed in one of the bays on the second floor facing the street. Many visitors came up to give their opinion. Unsurprisingly, the CRMS experts were sceptical about what they saw as an anachronistic fantasy. Vandenhove invited other colleagues, notably Aldo van Eyck, who he had met through his friend, historian and critic Francis Strauven. The Dutch architect’s negative opinion in front of the Rue Saint-Pierre façade made him waver, and realize that the contrast between old and new was too sharp.

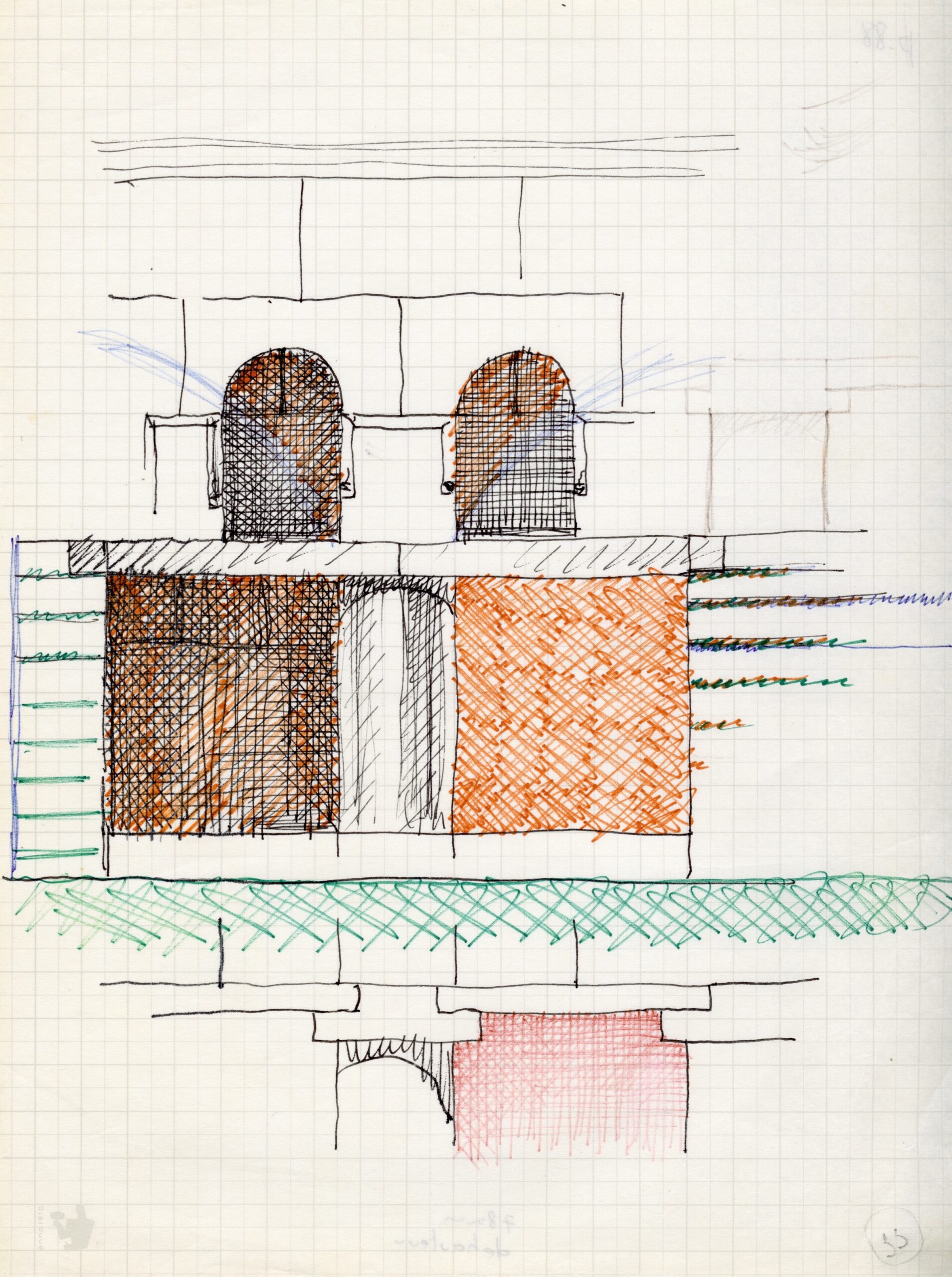

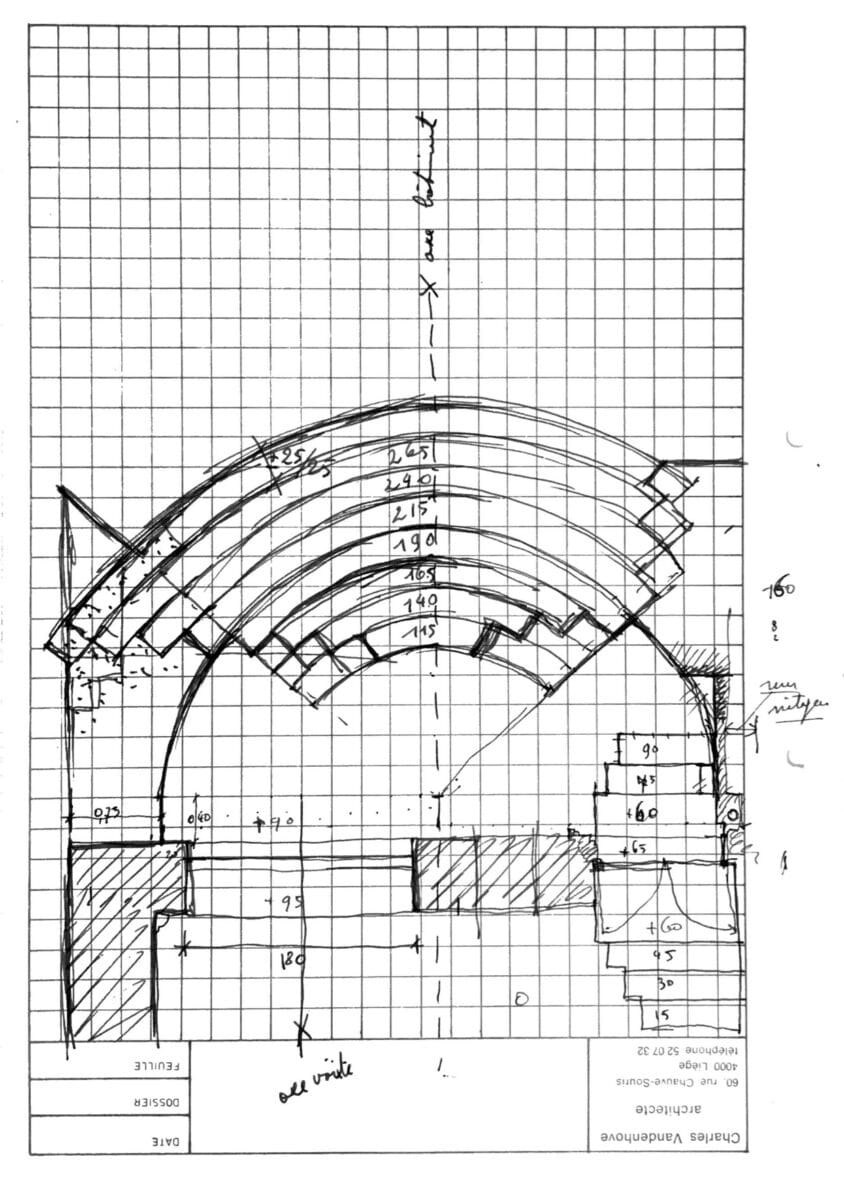

At the end of 1979, Vandenhove organised a decisive trip to Venice with his collaborators to revisit in detail the works of Carlo Scarpa, which he had discovered a few years earlier. Entitled ‘Venice, Christmas 1979’ and inspired by both Venetian Gothic façades and those of the Banca Popolare di Verona, a plan, section and elevation sketch introduces the idea of crossing two cylindrical columns, which were thinner than the I-beams and allowed a smoother circulation of light.

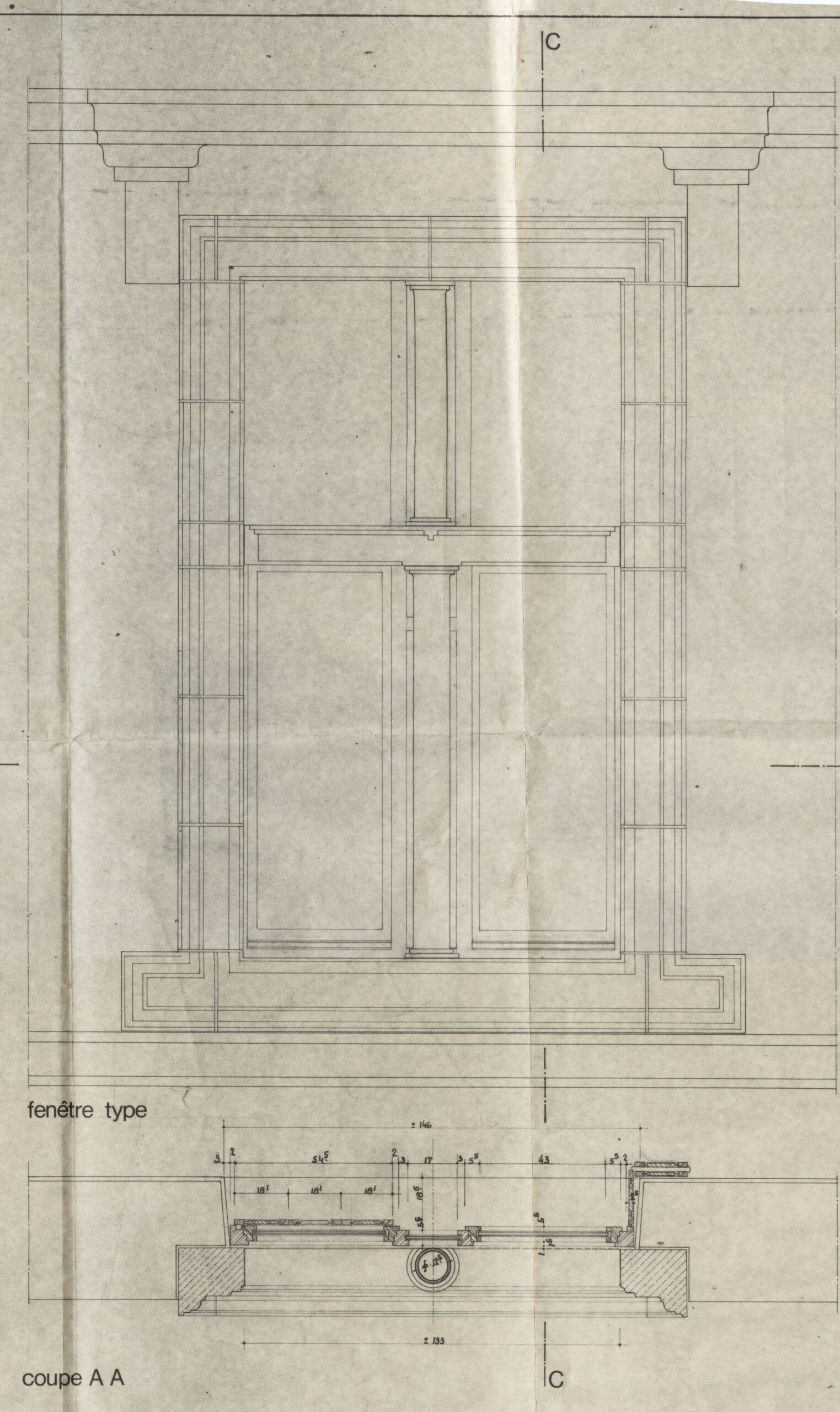

Back to Liège, the design was further refined and stabilized in January 1980. The transom takes the form of a finely moulded cornice, separating the mullion into two superimposed colonnettes, fitted with stylized bases and abacus.

One discreet detail is directly borrowed from Scarpa: the stepped moulding is turned over at the centre of the crosspiece to form a convex, inverted pyramid motif, a distant descendant of the classical modillion.

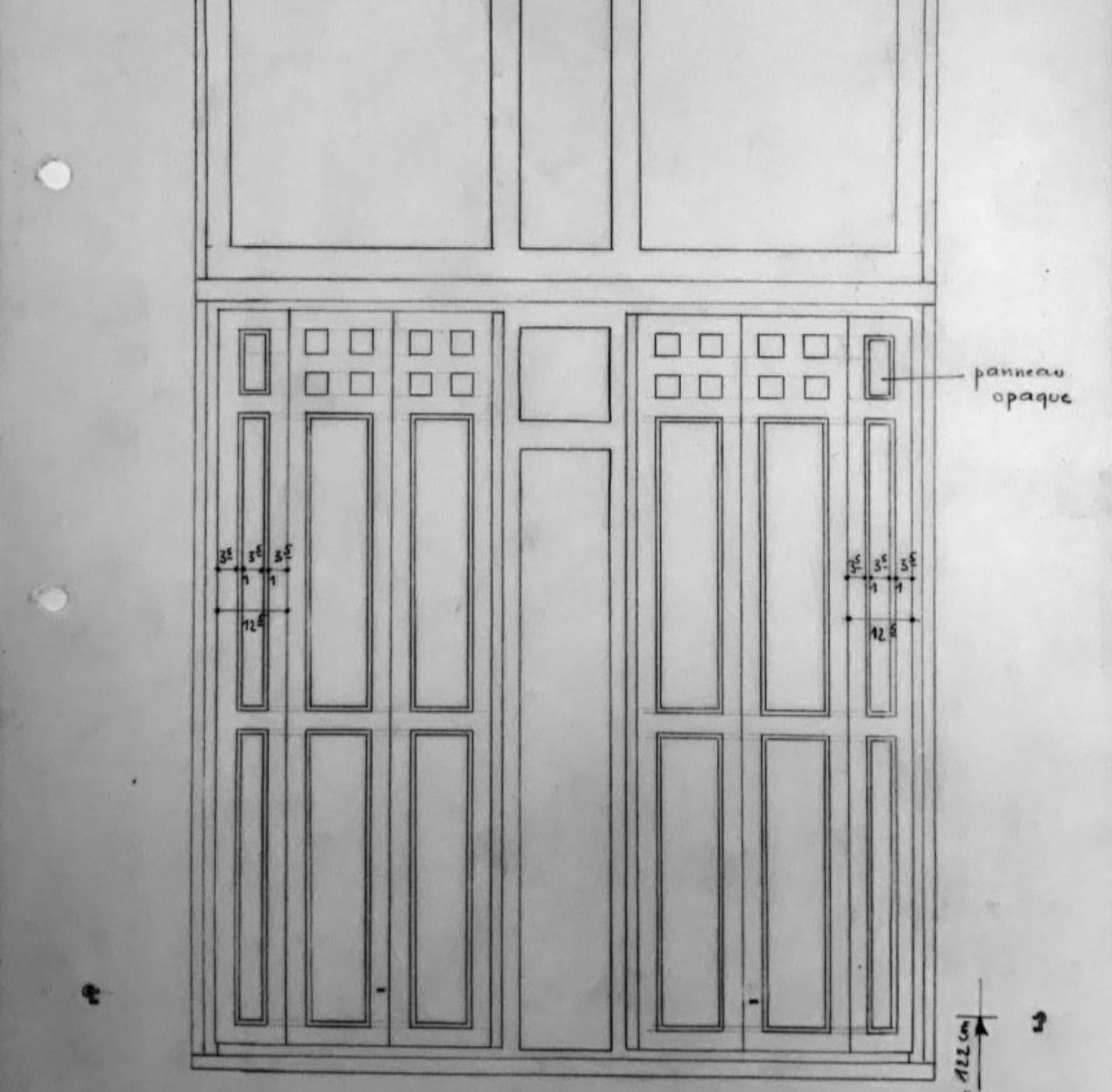

As at Castelvecchio in Verona, the stone crosspiece and wood window frame are dissociated, sliding one behind the other. In 1980, the design of the oak frame became even more independent. It was divided not into two but into three vertical glazed bands: two wider peripheral bands, each equipped with an opening sash in the lower register and a narrower middle band, showcasing the mullion-forming column. A wooden shelf, in the form of a square openwork grid, refines the opaque part that conceals the transom. The three-leaf interior shutters, a jewel of cabinetmaking, are fitted to the sashes, folding down onto the splaying and trumeau.

Made-to-measure by the workshops of local cabinetmaker Franz Baumans, the varnished oak frames, all identical but also all different, fit the slightly different dimensions of each bay. Repeated thirty times—18 double windows, 15 of which with the new crosspiece, and 10 single windows—the new window design plays a major role in the unity and character of the whole. With Torrentius, Vandenhove explored new design paths where architecture derived less from the overall morphology of volumes than from the form and repetition of its elements.

Pareidolia

From one drawing to the next, it is fascinating to observe the gradual refinement of the window arrangement, from the delicately profiled cast bronze elements of the crossing to the sophisticated assemblies of the oak frames. It is as if, in contact with Torrentius, Vandenhove’s architectural virtuosity gradually changed in scale and delved into a different degree of architecture detailing, not explored before. These themes may also have been fuelled by the architect’s trips to Italy in the early 1970s, in particular the one he made in the summer of 1973, accompanied by Geert Bekaert and Francis Strauven, in the footsteps of Andrea Palladio. A photo taken by Strauven shows Bekaert and Vandenhove from behind, contemplating the rear façade of the Malcontenta, no doubt discussing its proportions, its symmetry, its very free layout, the way the windows of the central span form an overall motif revealing the vaulted profile of the grand salon on the outside.

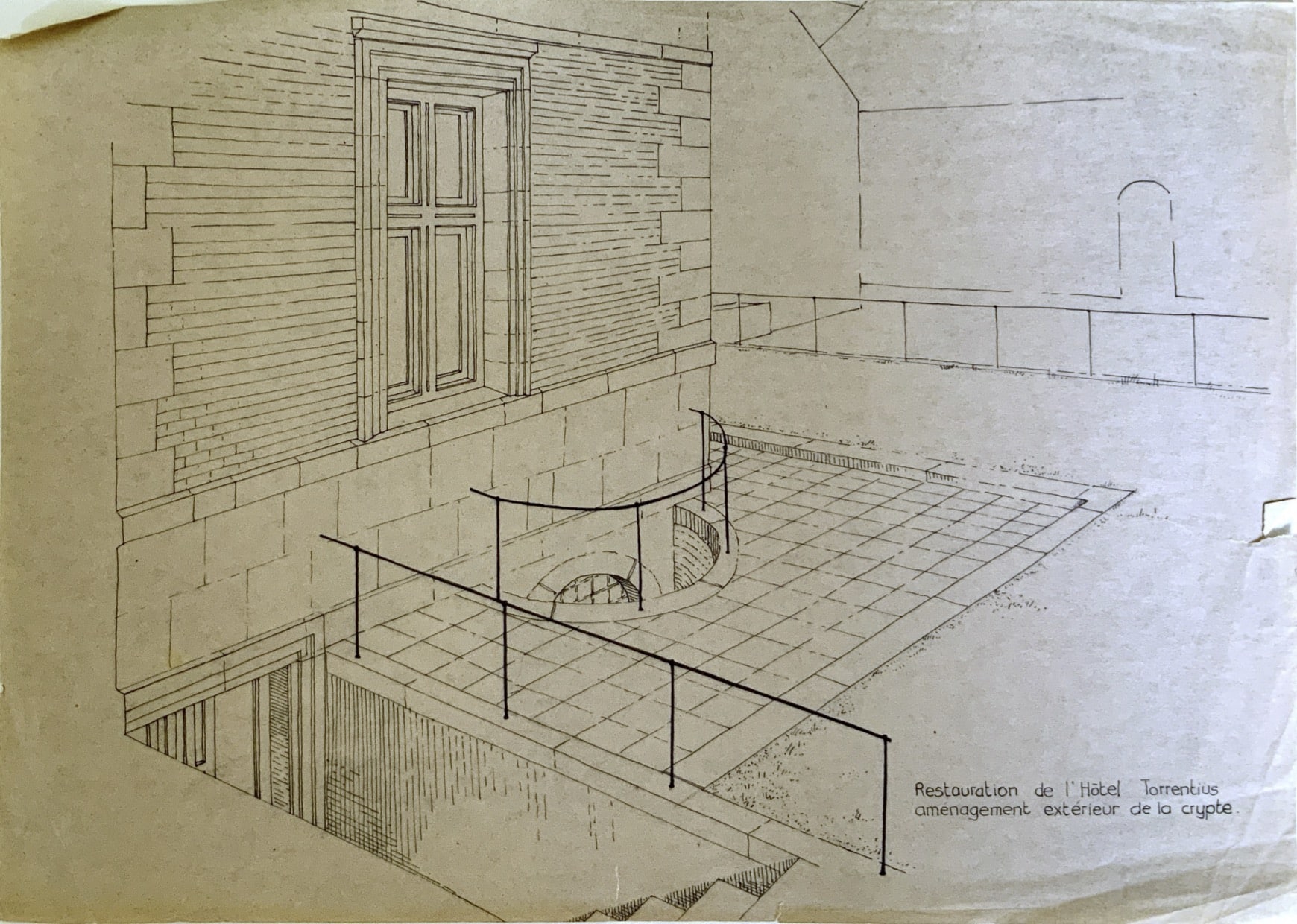

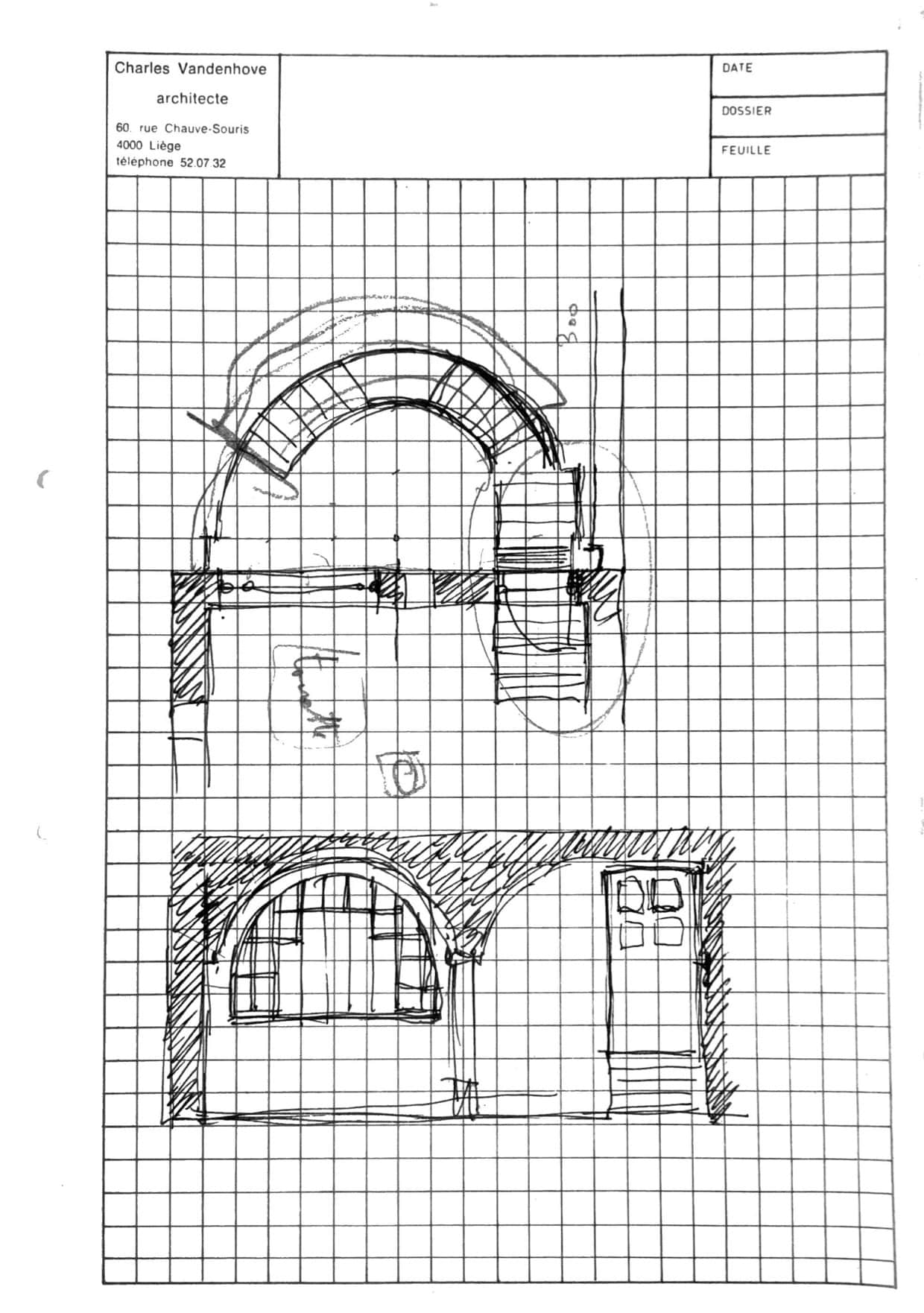

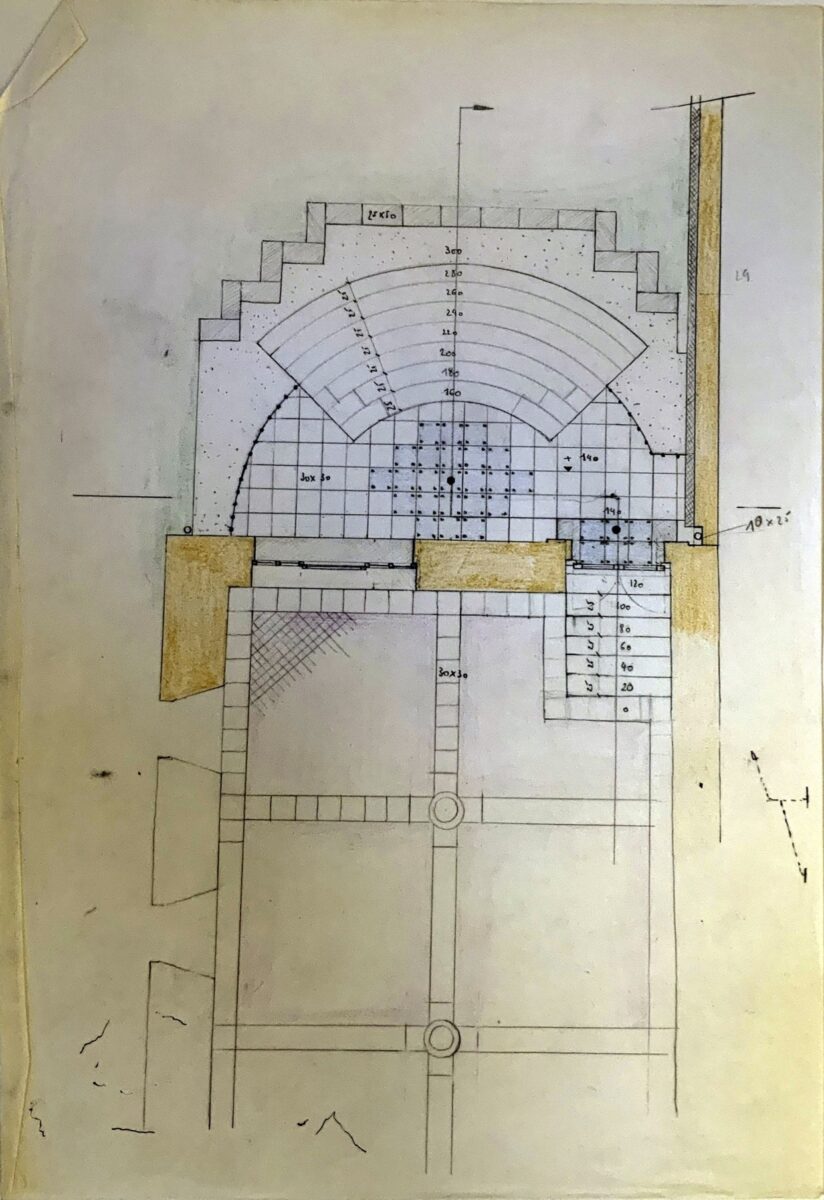

Two areas of Torrentius’s work bear witness to this kind of reflection: the restoration of the entrance porch—which had been dramatically widened and heightened in the mid-20th century with steel beams—and the development of the south gable of the main wing, including the excavation of an English courtyard to serve and illuminate the cellar floor. In both cases, Vandenhove multiplied the variants of the elevation in countless sketches.

In the case of the south gable, one problem was the shape of the new window(s) of what the architect called the ‘crypt’, a beautiful room consisting of six brick cross-vaults supported by two columns.

After testing arched or pyramid-shaped, single or twinned, symmetrical or non-symmetrical openings, Vandenhove decided to restore the two existing small cellar windows, cut into the bluestone of the basement. He underpinned them with a reinforced concrete shelf that forms the lintel of two large windows separated by a central concrete column. The anthropomorphic character of the design is further enhanced by the semicircular shape of the English courtyard, which not only endows this mineral face with a big smile, but above all seems to put the façade on show.

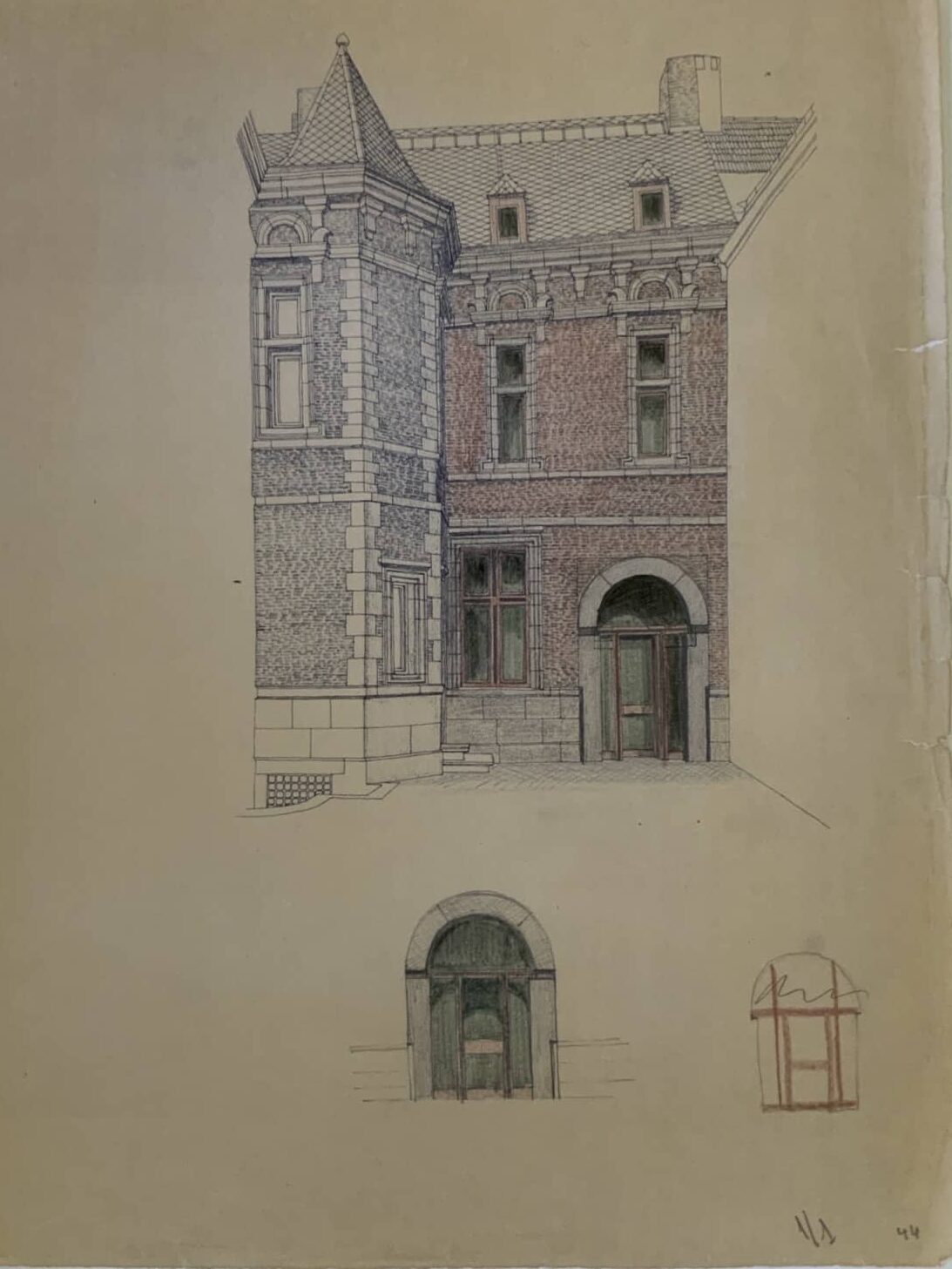

But this anthropomorphism is even more obvious in the case of the entrance porch. After an initial identical reconstruction solution was submitted to the CRMS in May 1978, the problem of inserting a narrower rectangular doorway into the courtyard portal, crowned by a semicircular arch, led to considerable changes in the design.

In the final version, which could be described as Mannerist, a square bossed bluestone cladding finally conceals the new interior barrel vault. The glazed section was cut through it in a pyramidal pattern. Two cast bronze half-columns flank the doorway, forming a strange serlienne, and supporting the corbelled stone courses. Two oculi, cut into the stone in line with the columns, echo their circular profile. Fitted with coloured glass—the same red as the stripes that Daniel Buren printed on the enamelled sheet metal covering the interior vault—they are like two eyes that gaze out at visitors as soon as they cross the threshold of the mansion. The whole porch becomes a quasi-theatrical device that dramatizes the entrance sequence and condenses, as a metonymy would, the new visage of Torrentius.

At once, the architect’s self-portrait and the architecture’s personification, this visage that one perceives through a process of pareidolia, on the façade of the former palace bears witness to the intense face-to-face between Vandenhove and Torrentius. It also seems to give an unwitting illustration to the intriguing definition of architecture given by Aldo Rossi at the beginning of his Scientific Autobiography, published at the same time as Torrentius was transformed by Vandenhove: ‘From a certain point in my life, I considered craft or art to be a description of things and of ourselves.’[5]

Notes

- Pierre Colman, ‘L’Hôtel Torrentius à Liège. Étude historique et archéologique’, in Architecture pour Architecture. Hôtel Torrentius, Lambert Lombard 1565, Charles Vandenhove 1981, ed. by Pierre Colman & Geert Bekaert (Bruxelles: Édition du ministère de la Communauté Française, 1982), n.p.

- The mortuary clinic (1958–1961), the book warehouse (1961–64), the psychiatry department’s research laboratories (1961–66), the Lucien Brull university residence (1962–67), the blood transfusion centre (1963–67), the physical education institute (1963–1972).

- Geert Bekaert, ‘Modernité et tradition en architecture’, in Charles Vandenhove, ed. by in François Chaslin (Liège: Mardaga, 1985), 98.

- Bekaert, ‘La mort conjurée’, in Architecture pour Architecture, n.p.

- Aldo Rossi, A Scientific Autobiography, trans. by Lawrence Venuti (Cambridge (MA): MIT Press, 1984), 1.

Pierre Chabard is is an architect, critic and historian of architecture and urbanism. He is currently Associate Professor of history and theory at the School of architecture Paris-la Villette. Author of a PhD about Patrick Geddes’ Cities Exhibitions, his current researches deal with social and cultural history of architectural mediations in the postmodern era. He is the author and editor of various books and founding member of the French journal Criticat (2008–2018), he now runs the Éditions de la Villette.

– Lera Samovich