Cedric Price: Urban Spaceman

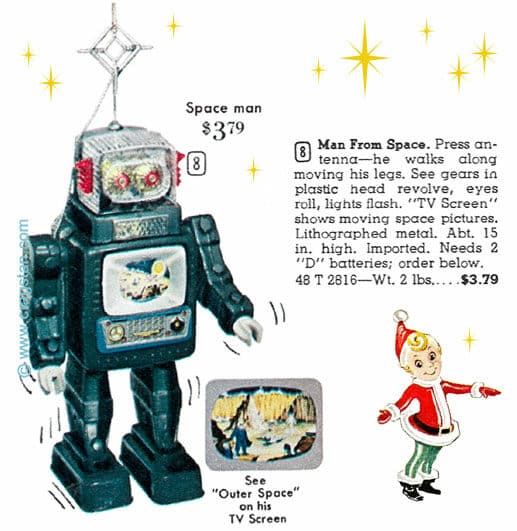

Laid down facing upwards and spread evenly on a neutral surface, 13 tin toys pose for a shot. Cedric Price’s robot collection – battery powered or clockwork, says the caption – includes a mechanical bird and rabbit, several spaceships, spacemen and robots. Their distinctive features intimate specific names, makers and dates. Starting with the largest – the bottom left in the photograph – and moving clockwise, we find that Price gathered: a Television Spaceman (produced by Alps Shoji Toys between 1961 and 1965); a Flying Saucer Z-26 (Yoshia, n.d.); a Moon Rocket (Masudaya, n.d.); a Gear Robot (Horikawa, 1964); a Planet Robot (Yoshia, 1960); a Moon Explorer M27 with Rocket (Yonezawa, 1963); a High Wheel Robot (Yoshia, 1964); a Machine Robot (Horikawa, 1963); [1] a Space Conqueror S-5 (Daiya, 1962), [2] and a Robot with Spark (SY/Yoneya, 1960s). [3] These popular Japanese toys were best-sellers that appeared in early-1960s Christmas catalogues in the US and UK, a time when Price’s and Joan Littlewood’s Fun Palace project was on the loose. The project had made news on Sunday 28 April 1963, when Littlewood introduced the Fun Palace in the BBC programme ‘Monitor’. Following a carefully planned publicity drive, the MP, journalist and Fun Palace contributor Tom Driberg followed up the idea of a ‘Vauxhall Gardens-plus, exploiting for pleasure the most advanced technological developments of this age’ in his Sunday Citizen column a week later. [4] The Fun Palace went viral in British press, regularly making the headlines over the following three years. In 1963, the Christmas catalogue of American retailer Montgomery Wards advertised in colour the Alps Television Spaceman: ‘Man From Space – Press antenna – he walks along moving his legs. See gears in plastic head revolve, eyes roll, lights flash. ‘TV screen’ shows moving space pictures. Lithographed metal. Abt. 15 in. high. Imported. Needs 2 ‘D’ batteries; order below 48 T 2816 – Wt. 2 lbs…. $3.79’. [5] First sold in 1961, by 1966 a restyled version introduced some plastic components – the shoes, battery door and the red circular radar in place of the antenna.

Antenna-equipped but missing its plastic visor, Price’s Television Spaceman may have enjoyed a particular life of its own. London drama critic Alan Brien had spotted one robot toy amidst some film material in Littlewood’s flat during an interview at the peak of Fun Palace activities. In his article for American Vogue, 15 September 1964, Brien recounted the environs he saw:

‘It was a long and thin (room) with a romantic Parisian panorama of chimney pots from the window. It contained a double bed guarded by two large movieolas, a work bench piled with coils of wire, two tape recorders, a typewriter, equipment for cutting and cementing film, a model robot, and a stack of correspondence.(…) / Above the mantelpiece was a picture of the Virgin Mary upon whose face someone had stuck a pair of red Marilyn Monroe lips cut from a magazine. Next to this was a long penciled series of quotations beginning with “only connect” and “the slow burial that begins with birth”. On the other wall there were Ordinance Survey maps of the East End and aerial photographs of the docks. The top letter was from her lawyer. He said he was having great difficulty in framing a legal definition of her Project’. [6]

At one point during the course of the interview, Littlewood – with some exasperation – referred to a film that she was making linked to the Fun Palace project:

‘“Work and Leisure” – the words don’t mean anything anymore. I’ve been out with the camera shooting faces. I don’t know what I‘m going to do with the film. I think I’ll burn the bloody lot. I call it a self-educating Fun Palace. It’ll be a nucleus. I’m fed up with that acting stuff / You know those councillors are still making parks for people to keep off the grass in. I’d like to sabotage the whole theatre –museum-art-gallery bit. You educate yourself through your job. You never learnt anything at Oxford. We’re already in the middle of a revolution. Everything up to now has been pre-history. I want action. I want to canalize violence in my twenty-one acres (…)’. [7]

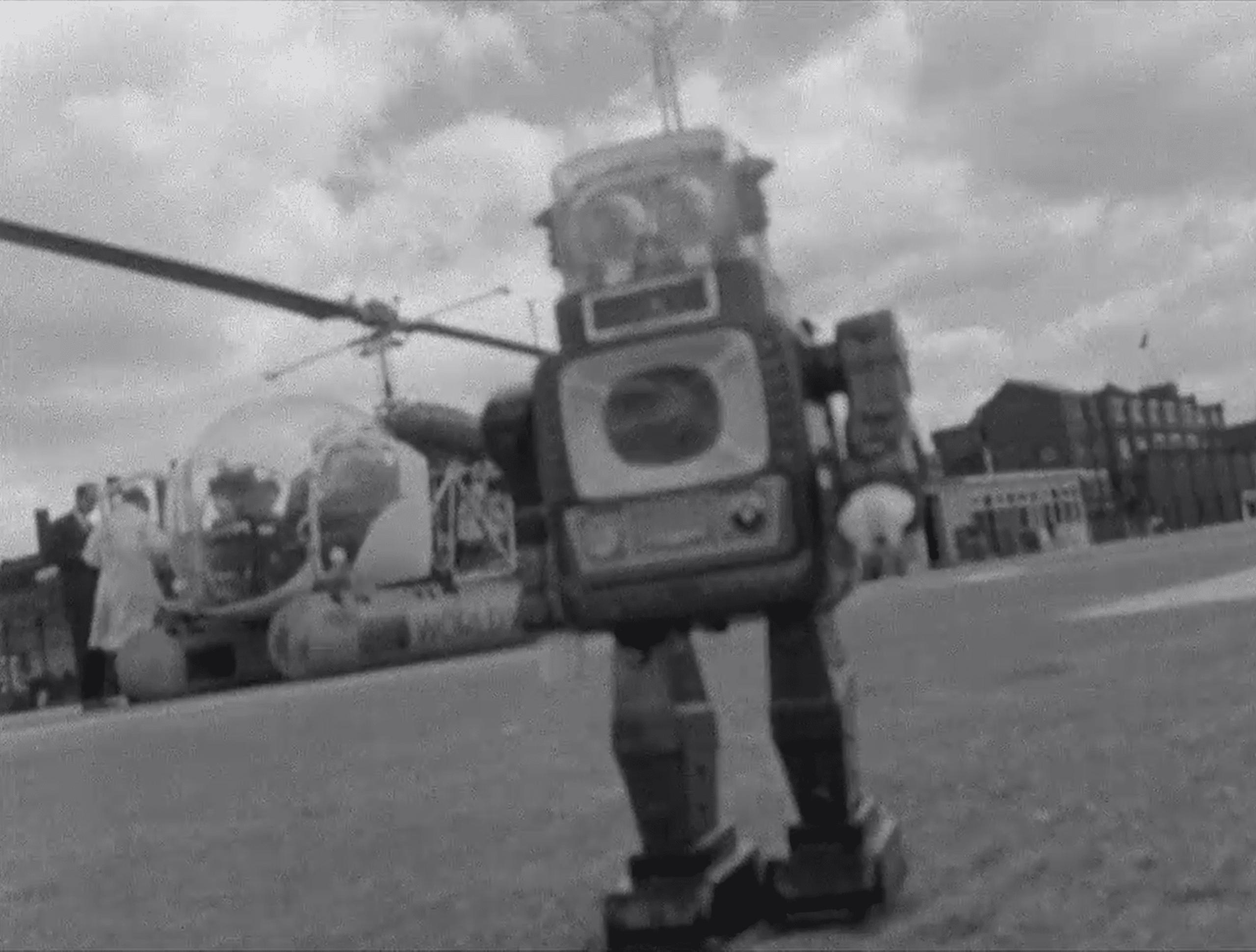

‘London from the Air 1 (Fun Palace Outtakes)’ is part of Littlewood’s collection of over 60 short films from 1963 – silent, 16 mm black and white, and associated with the Fun Palace – held at the British Film Institute. [8] The 3-minutes of footage, shot from a helicopter, documents London’s docks, with their patches of uncommitted land, and the Battersea Park funfair, one of Littlewood’s key pleasure sites by the river Thames. After a long landing sequence, a Television Spaceman appears on screen, walking towards the camera. The shot is strongly constructed. A low angle camera magnifies the antenna-geared, clumsy-moving robot that has just landed. The helicopter and its crew – Littlewood seems to be among them – lie in the background of the vast and empty landing platform. A comical shift in tone takes hold as this impersonator of technology fills the screen.

The related script ‘Pleasure Film: Assembly’ – an archival record associated with the Fun Palace film and held at the Canadian Centre for Architecture – positions this sequence in the overall montage. Once the flâneur-camera had closely scrutinized pleasure (or its absence) in London’s everyday life (the camera’s progressive detachment from the action was intended to reflect a generalised social condition of apathy) the film reaches its climax. The unexpected ‘robot doll walking computer singing as background’ (shot 62) is an embodiment of the script’s critical question ‘Who has all the fun? The actors? The planners?’ [9] The film closes with a nascent Fun Palace progressively sketched ‘white on black’ (shot 71) as London’s reality fades away – after ‘helicopter shot over London and river to last frame of mudflat’ (shot 69) and shot ‘dissolve mud to blackness’ (shot 70). As crane, helicopter, mono-rail and speedboats are drawn in – shots 72, 74, 75, 76 respectively – the creation of the Fun Palace and its surroundings, including the river and even the sun, is celebrated with ‘fireworks drawn falling into the river’ in the last shot of the 81 scripted.

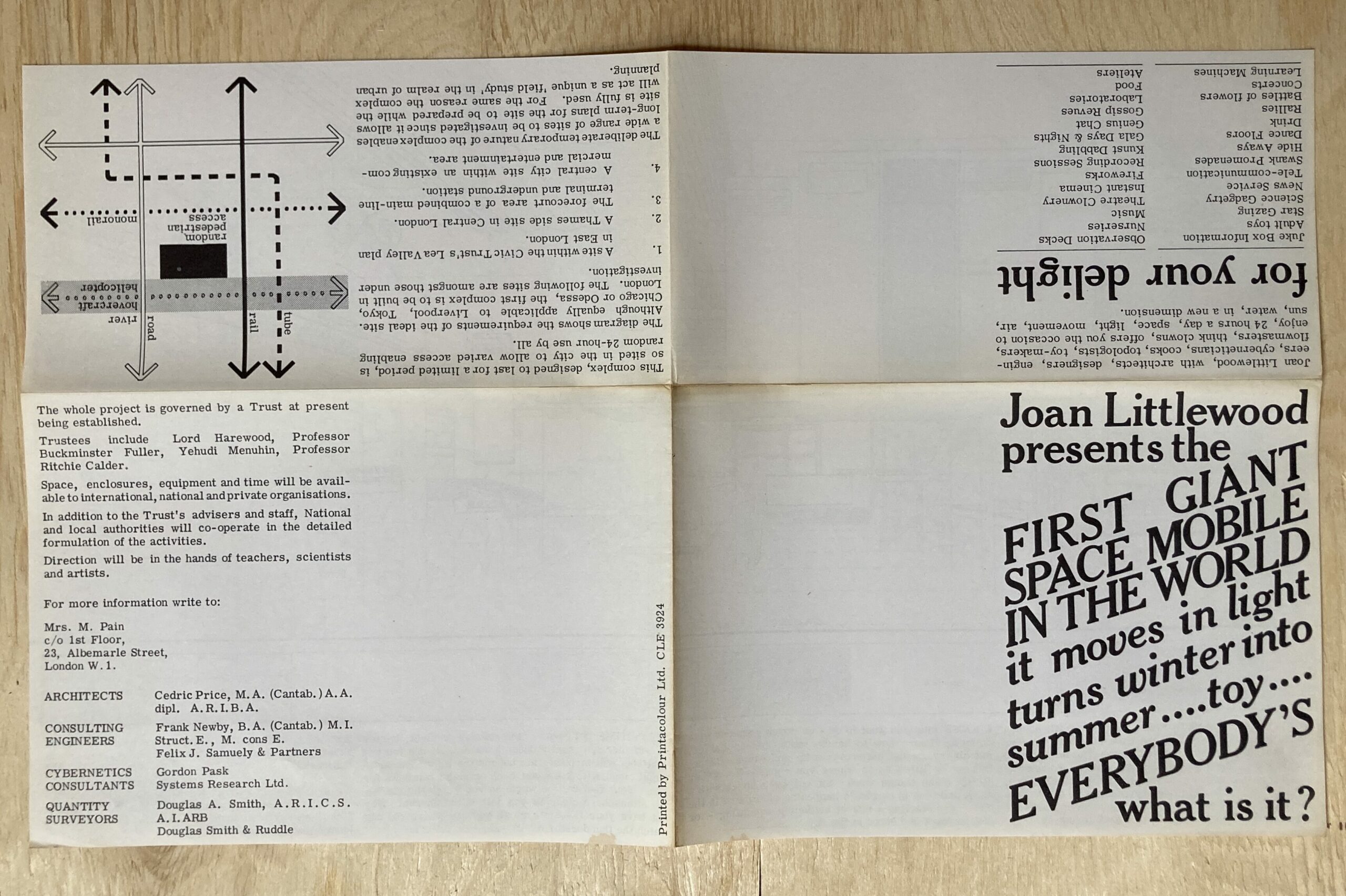

The camera transforms the Television Spaceman into a clown-like figure, whose performance for us intimates the role technology might play in charging social experience with pleasure. At the same time, the toy analogue exposes the uncanny affects to which technology gave rise in global social experience at the time, as these were precipitated in a range of sci-fi-infused cultural artefacts. If the images of ‘outer space’ that were apparently screened in the belly of this Japanese communications robot appear to modulate the wonder and distress brought about by Cold War space race, its pseudo-autonomous movements and intermittent flashing signals hint at the paradoxical emancipatory prospects of automation. Ultimately, the film transforms the robot from a Christmas commodity into a kind of personification of the Fun Palace itself, which like the toy, would act ‘for your delight’ – as the publicity of the project announced in its 1964 promotional broadsheet. [10]

Developed as a Brechtian gesture, one that introduces a critical suspension within the flow of events, the robot doll sequence aims to interrupt not only the plot in its shot-by-shot juxtaposition, but also our experience of watching it. The archival records seem to suggest that the film was intended to be broadcast on commercial television, [11] and this gives the specific choice of the Television Spaceman for the role of robot-clown a particular value – as the playful image of the release of the very technological device on which the viewer was watching it and its assumption of a different kind of agency. Situated as an element of the overall publicity strategy of the Fun Palace, the robot sequence mimics the ‘Message to Londoners’ that Littlewood and Price drafted to promote the project:

‘When it comes to enjoy ourselves, we think, feel and behave as we did a hundred years ago. We just haven’t learned how to enjoy our new freedoms: how to turn machinery robots, computers and architecture itself into instruments of pleasure and enjoyment. The truth is that the times are out of joint, and we know it. We have touched the moon, we have released the power of the atom, and yet we have hardly begun to understand this short-lived, unique, unrepeatable bargain – our stay on this planet […] We need, and have a right, to enjoy the totality of our lives. We must start discovering how to do so. This, in essence, is the thinking behind the concept of the Fun Palace’. [12]

Whether Price’s visor-less Television Spaceman that now rests peacefully in the Drawing Matter collection is the same one that had its screen debut in the Fun Palace ‘Pleasure Film’ is an open question – as it is the fate of the sparse film. At any rate, the little toy remains an unexpected witness to a complex of ideas whose day has not yet passed. And perhaps, if we look closely enough, we might still see it spark, even twitch a little, from within the archival toybox.

Notes

- ROBOTapedia. Accessed 4 March 2021.

- Alphadrome. Accessed 4 March 2021.

- Attacking Martian. Accessed 4 March 2021. Details for the two mechanical pets have not been identified.

- Tom Driberg, ‘Tom Driberg writes about a dream-playground’, Sunday Citizen, 5 May 1963.

- Attacking Martian. Accessed 26 February 2021.

- Joan Littlewood by Alan Brien, Vogue, 15 September 1964, 190.

- Alan Brien, Vogue, 15 September 1965, 191.

- BFI Player. Accessed 4 March 2021.

- ‘Pleasure Film: Assembly’, 3, DR 1995:0188:525:003:003, Cedric Price fonds, CCA.

- Fun Palace Promotional Brochure, 1964. DMC 3182.

- Internal memo from P. Pain to JL, cc. CP, Ian Mikardo, dated 16.08.1964. Folder DR1995:0188:525:002:003, Cedric Price fonds, CCA. In Ana Bonet Miro, ‘From Filmed Pleasure to Fun Palace’, Arq (London, England) 22, no. 3 (2018): 215–24.

- ‘A Message to Londoners / WE COULD ENJOY OURSELVES. All about Joan Littlewood’s Palace of Fun’. Folder DR1995:0188:0525:001, Cedric Price fonds, CCA.