Pan Scroll Zoom 7: MOS

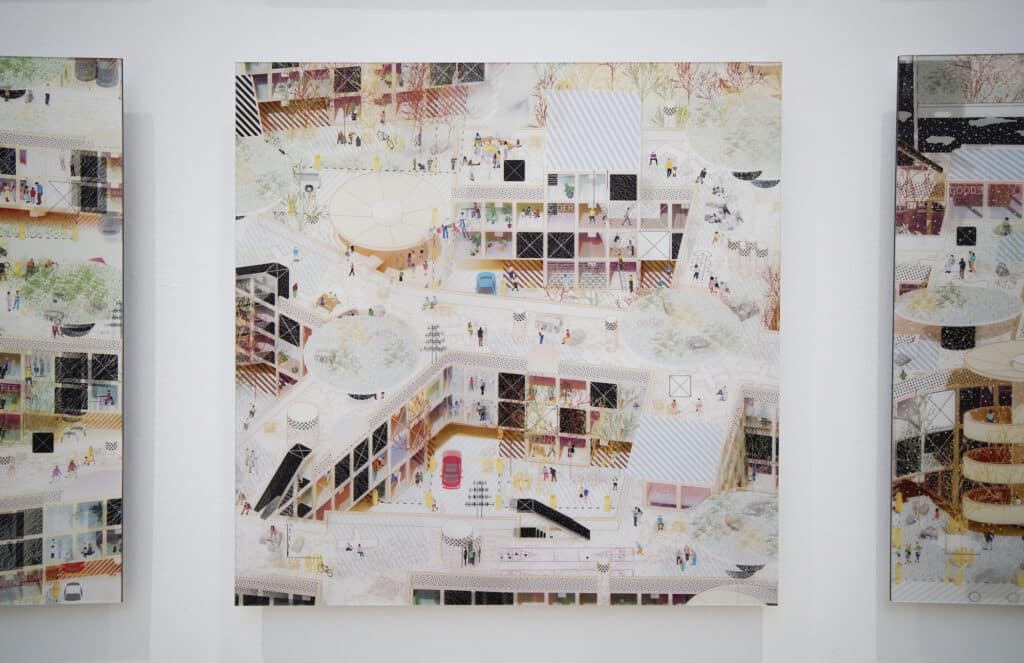

– Fabrizio Gallanti, Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample

This is the seventh in a series of texts edited by Fabrizio Gallanti on the challenges in the new world of online architectural teaching and, particularly, on the changing role of drawings in presentations and reviews. In this episode Fabrizio interviews Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample of the New York-based practice MOS.

Fabrizio Gallanti: This series was started to reflect on how remote teaching during the pandemic has changed the pedagogy of architecture. Overtime, it has slightly morphed to address more generally how we teach architectural design today. Throughout the series, the interconnection of research, teaching, and practice for architects who are both docents and practitioners has emerged as a recurring subject. As MOS, you run a design outfit together, but you teach separately, at Columbia University and Princeton University. I think it is interesting to see how that experience generates feedback loops with your own work. If I remember correctly, Michael, you told me that you were doing ‘projects on the phone’.

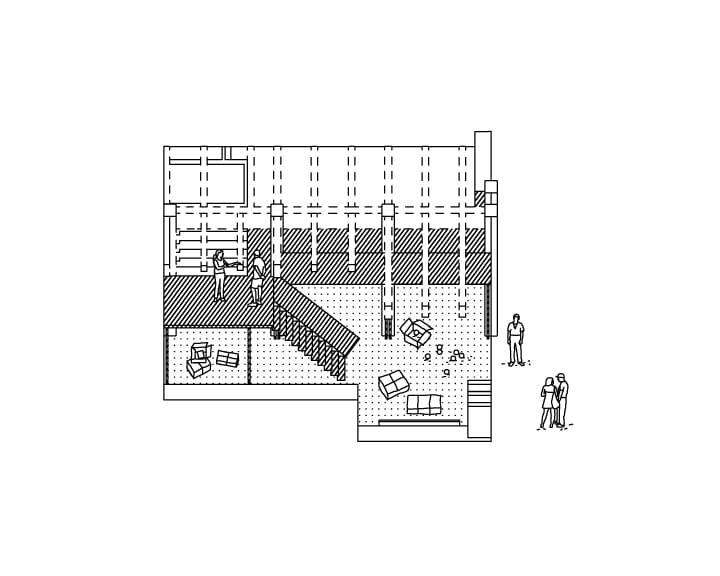

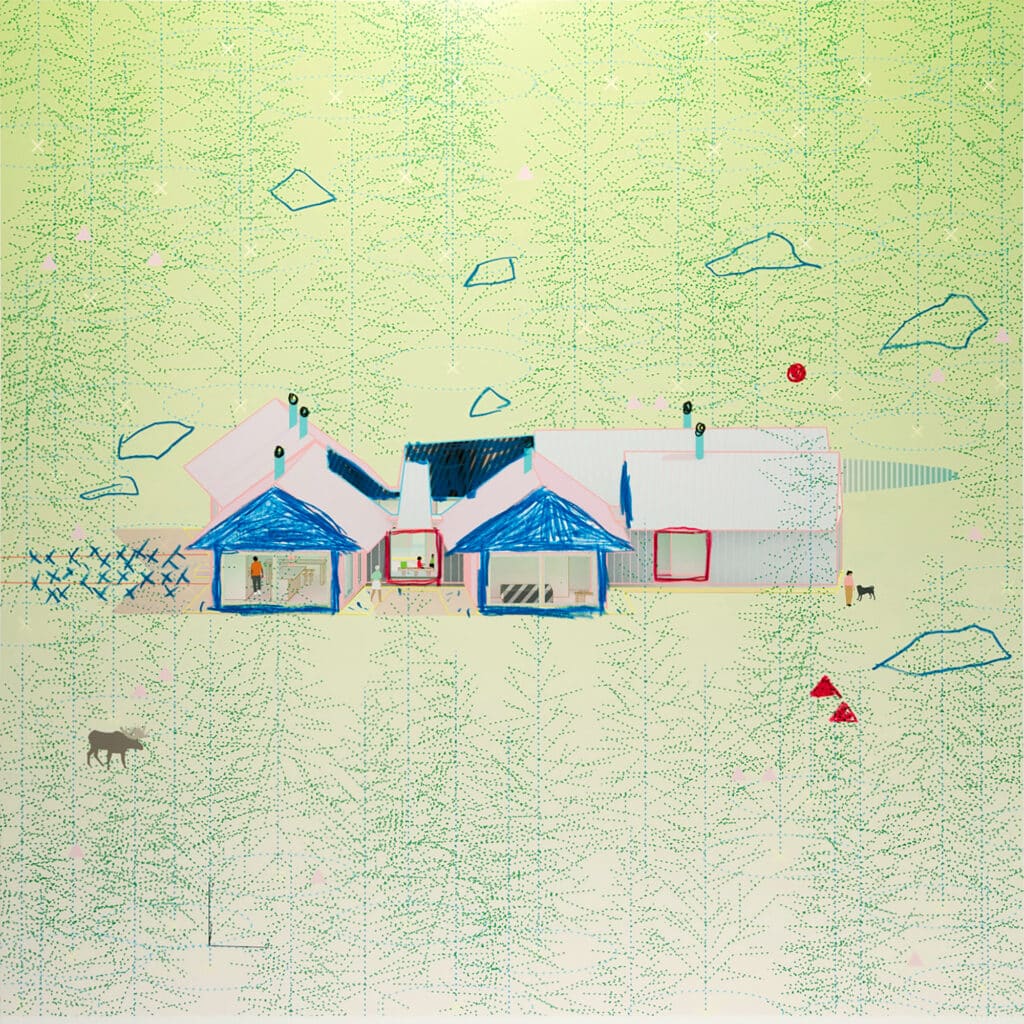

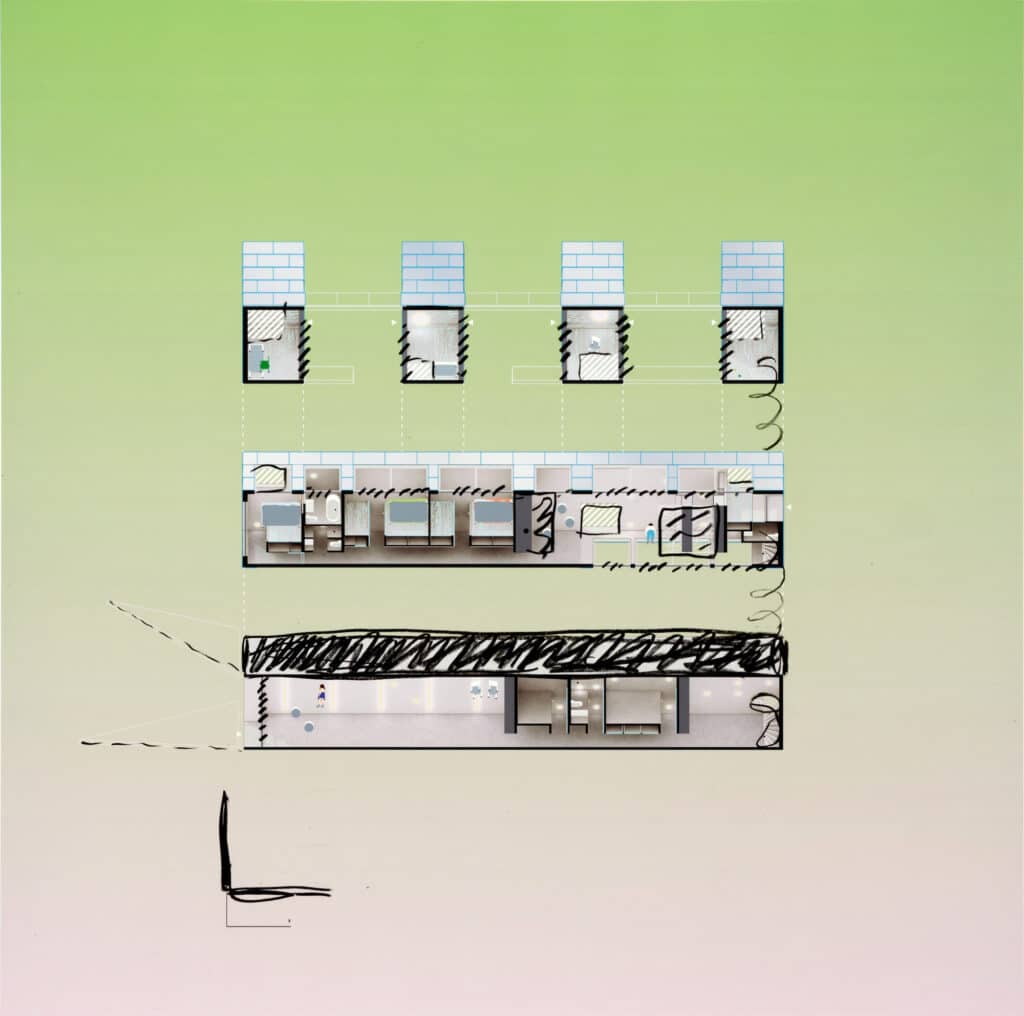

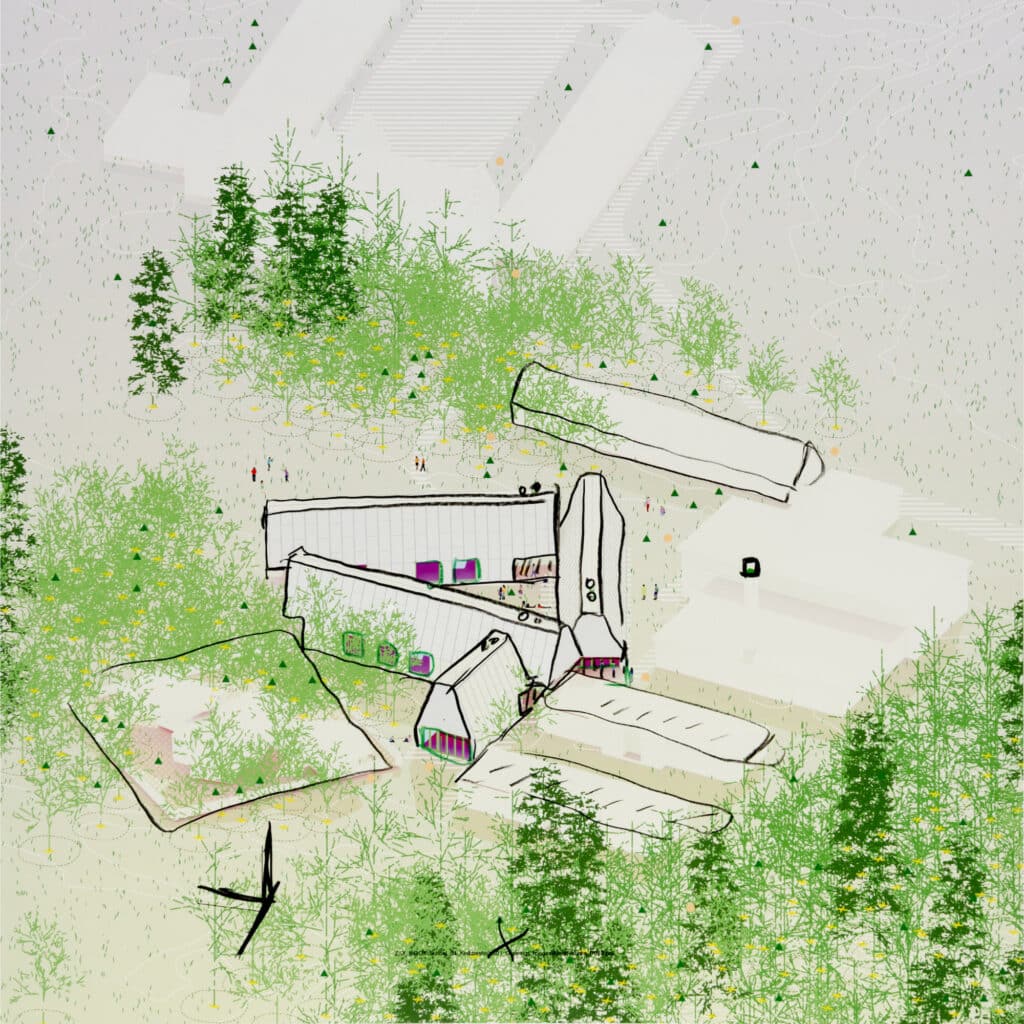

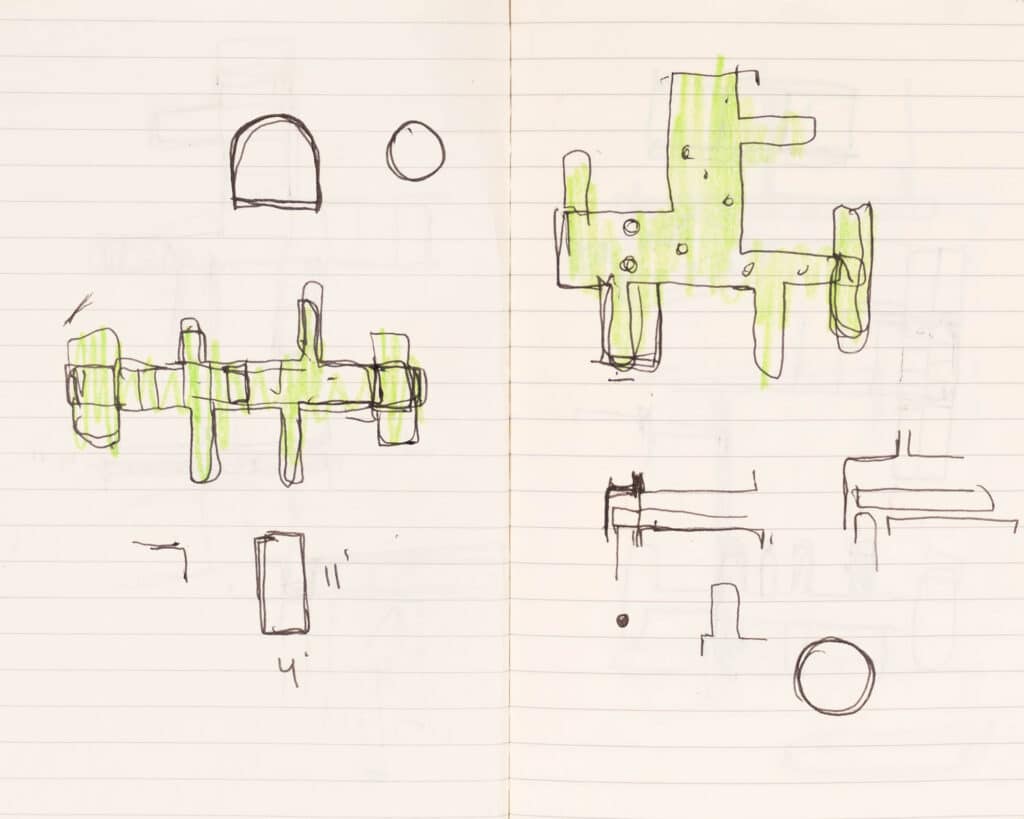

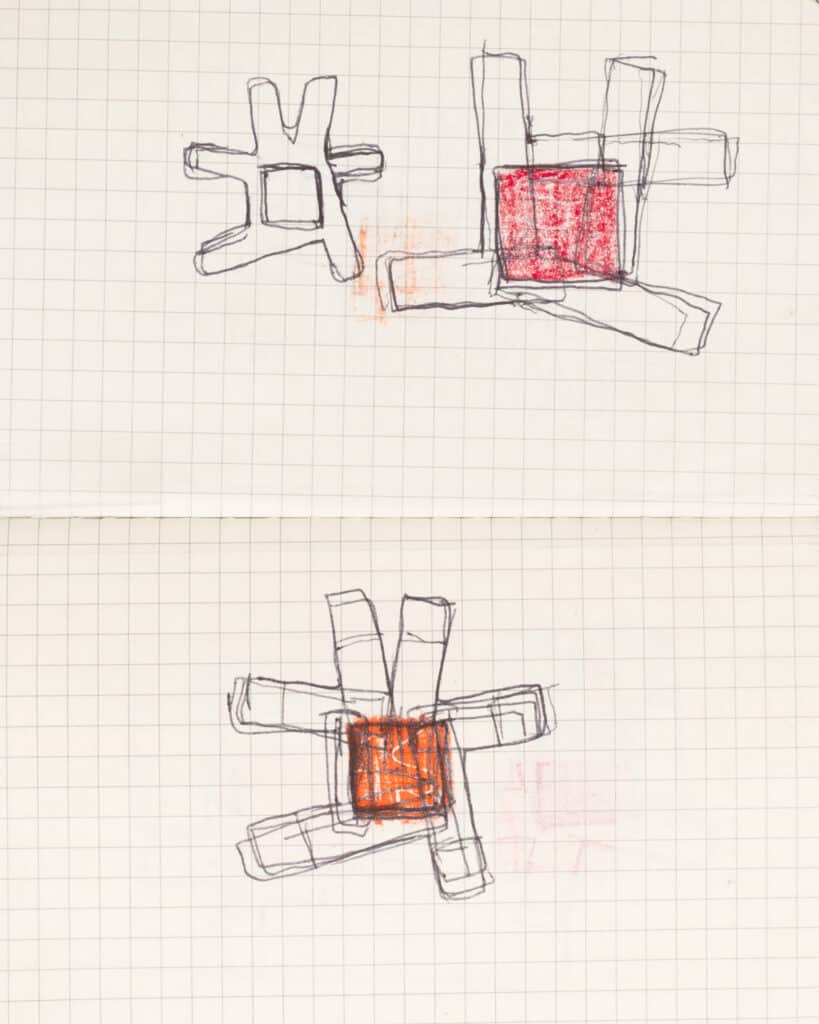

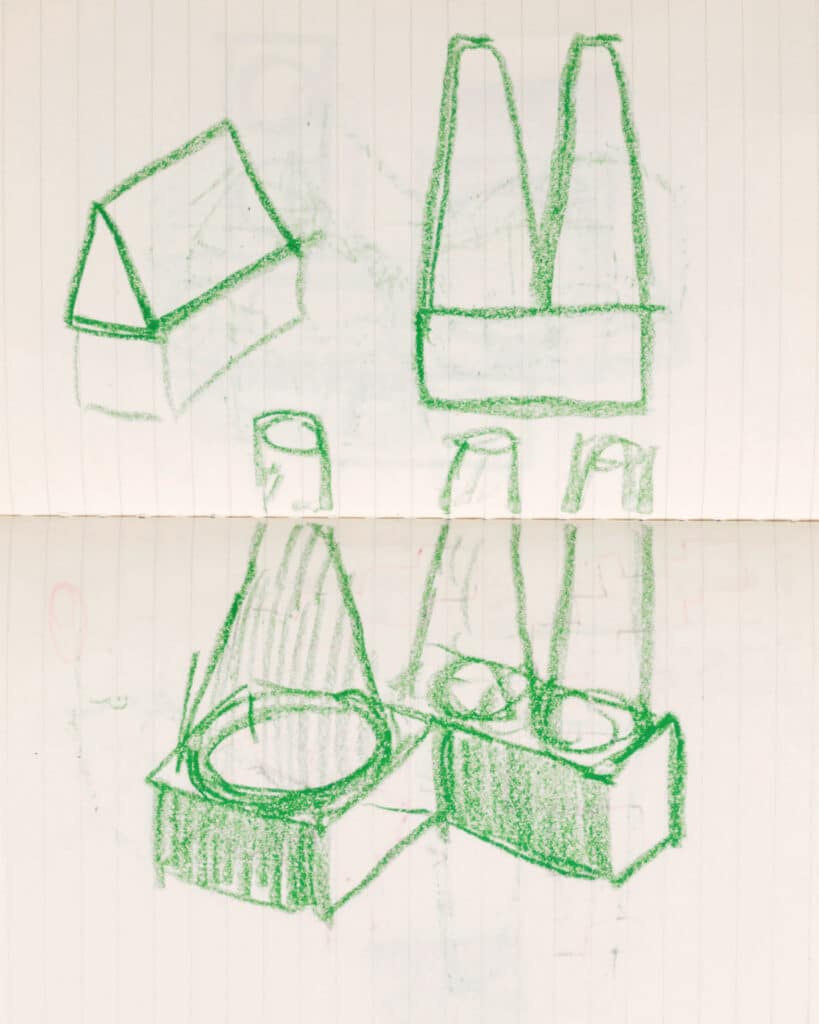

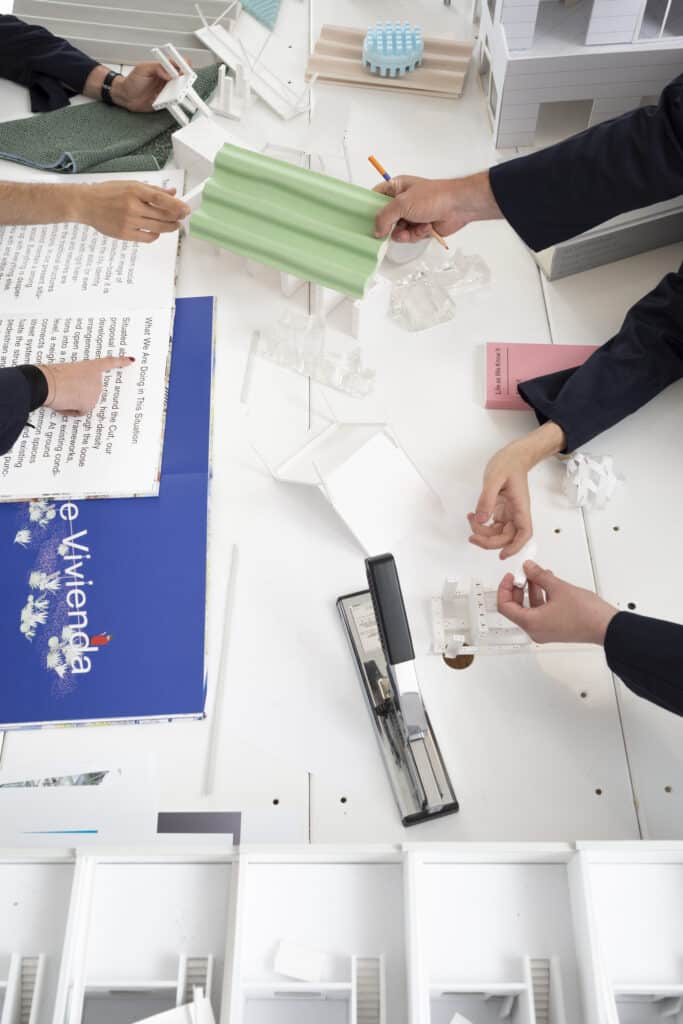

Michael Meredith: Yes, at the moment I am interested in drawing on the phone, a combination of annotation and sketches in a notebook, taking a photograph, sending an email. Drawings can convey information with a certain directness. In the office, that happens daily: receiving an image, drafting some changes or highlighting some important features with your fingers directly on the touchscreen, then describing what you intend through that graphic expression, either verbally or in a message.

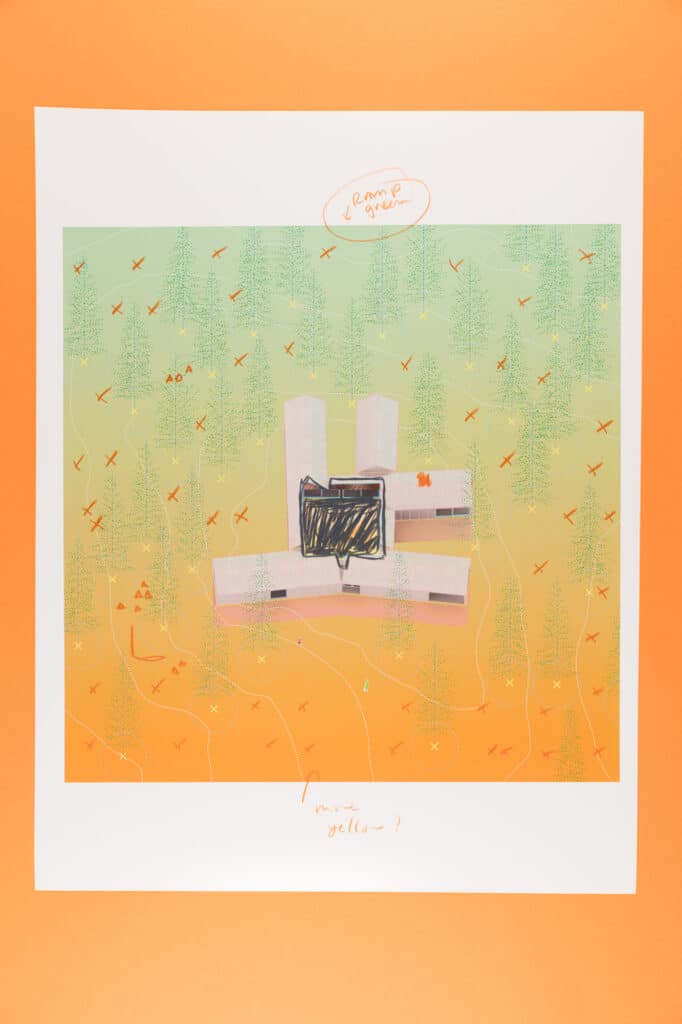

Hilary Sample: We also Finger Paint over a picture. This is similar to the ‘screenshots’ we use, freezing a view from a digital file over which other graphic information is then integrated. Often scribbling over them. These are quite raw and unfinished in general, yet they become fragments to better understand a project.

FG: These ‘screenshots’ are more authentic, quicker, perhaps dirtier, and allow you to reach different stakeholders during the process of design?

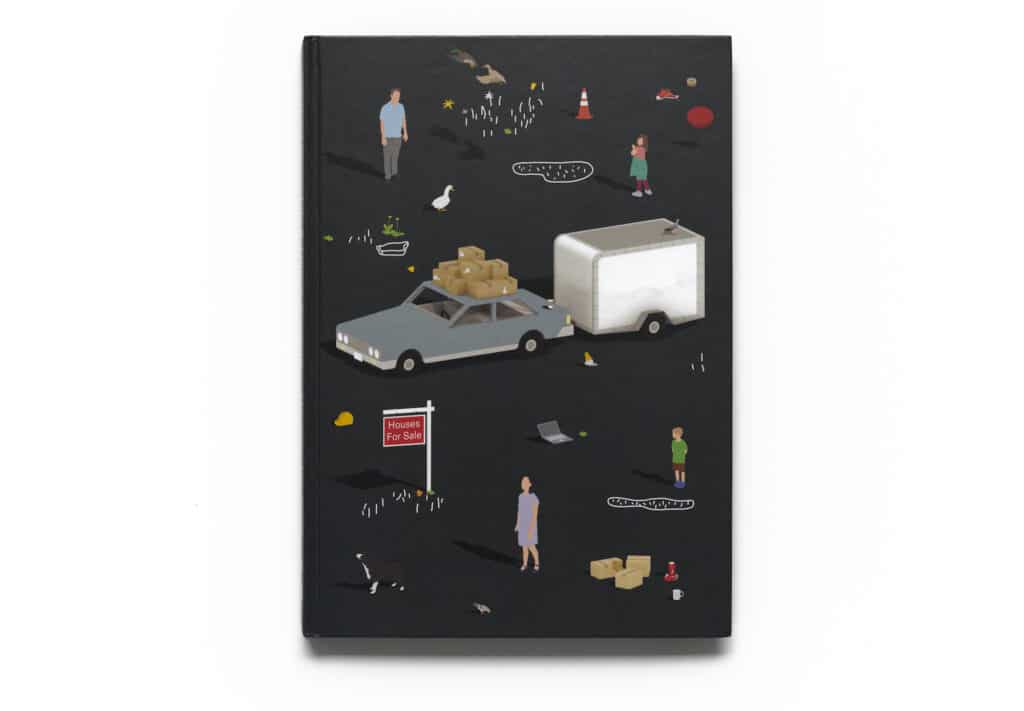

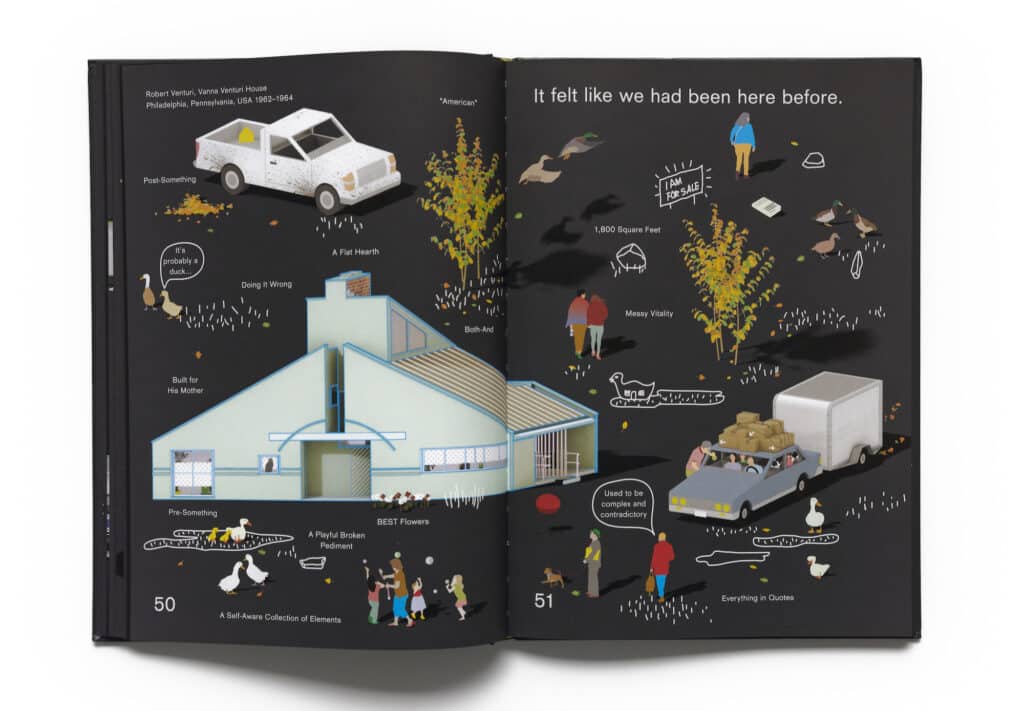

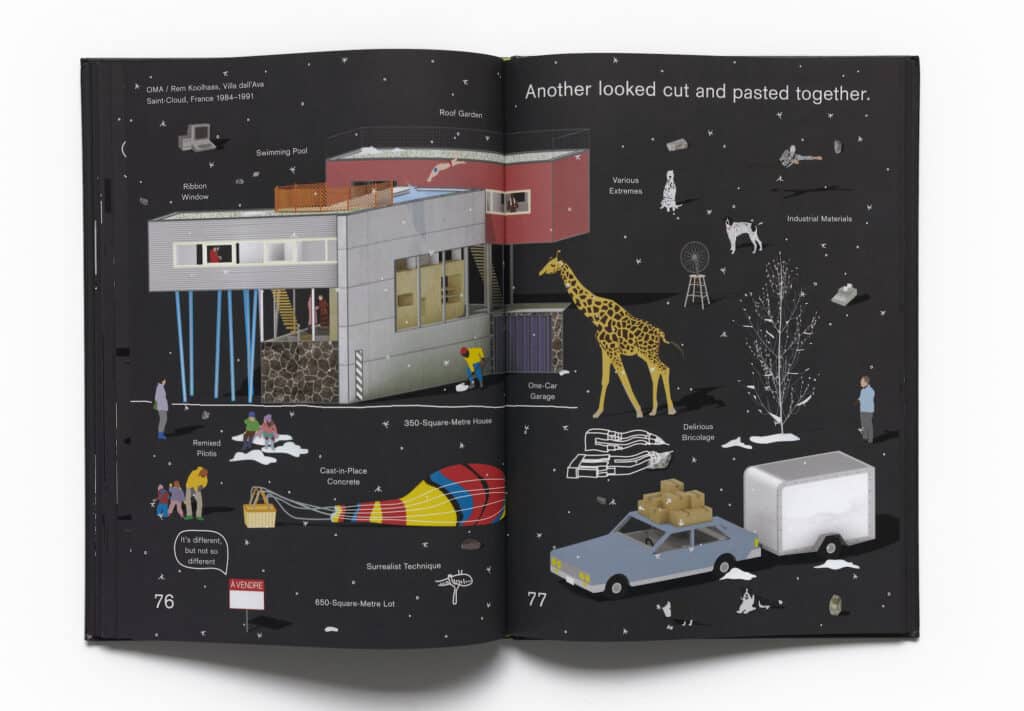

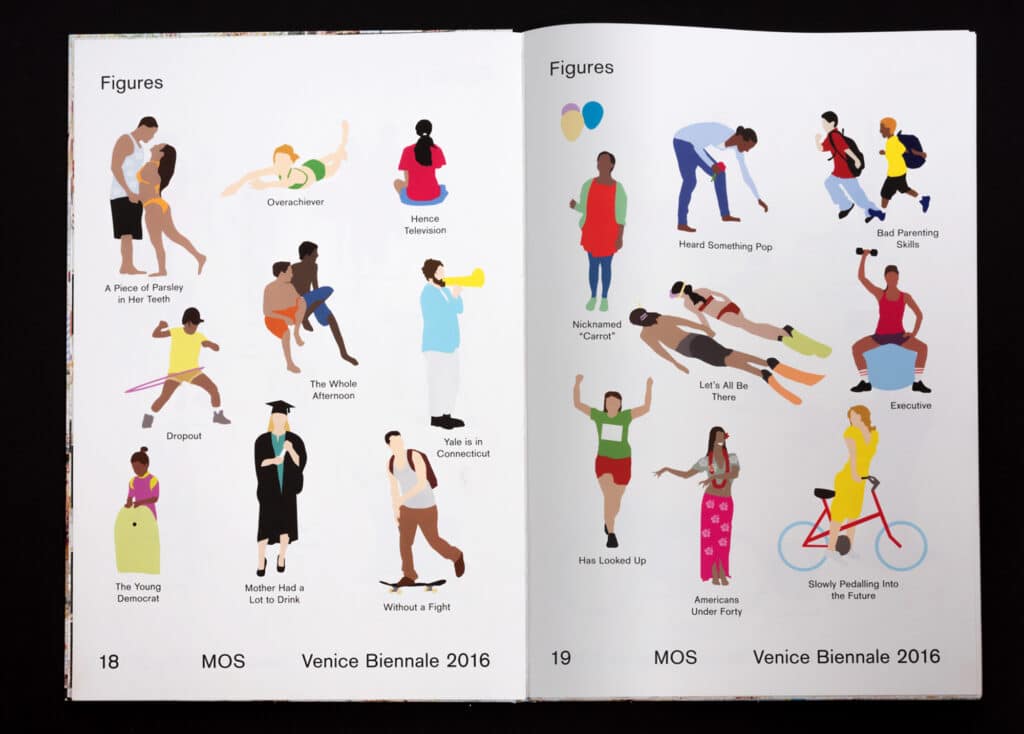

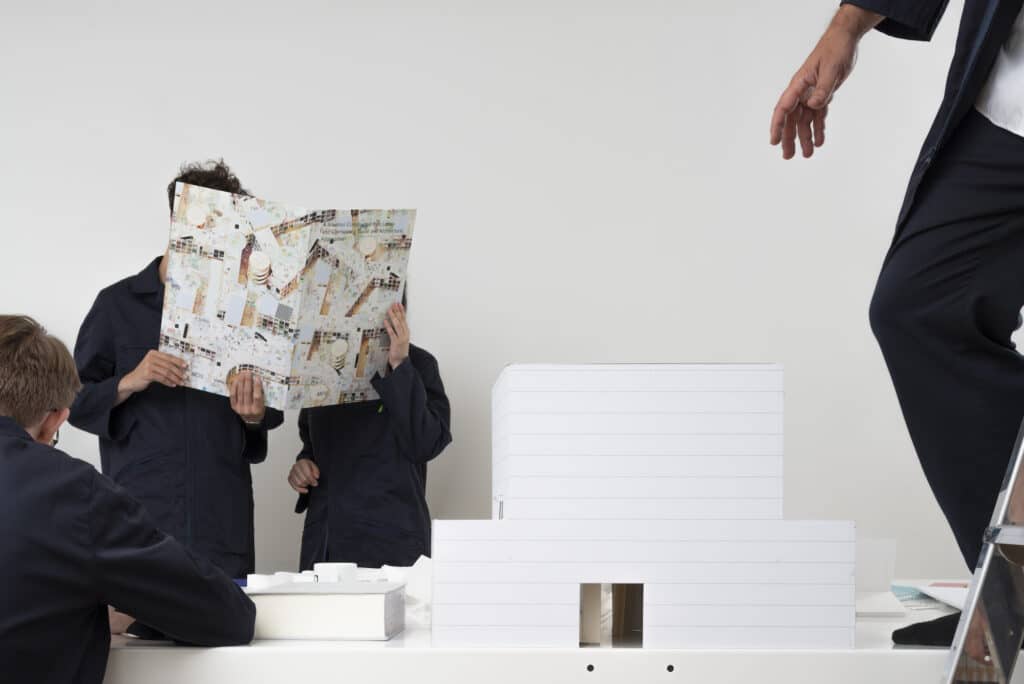

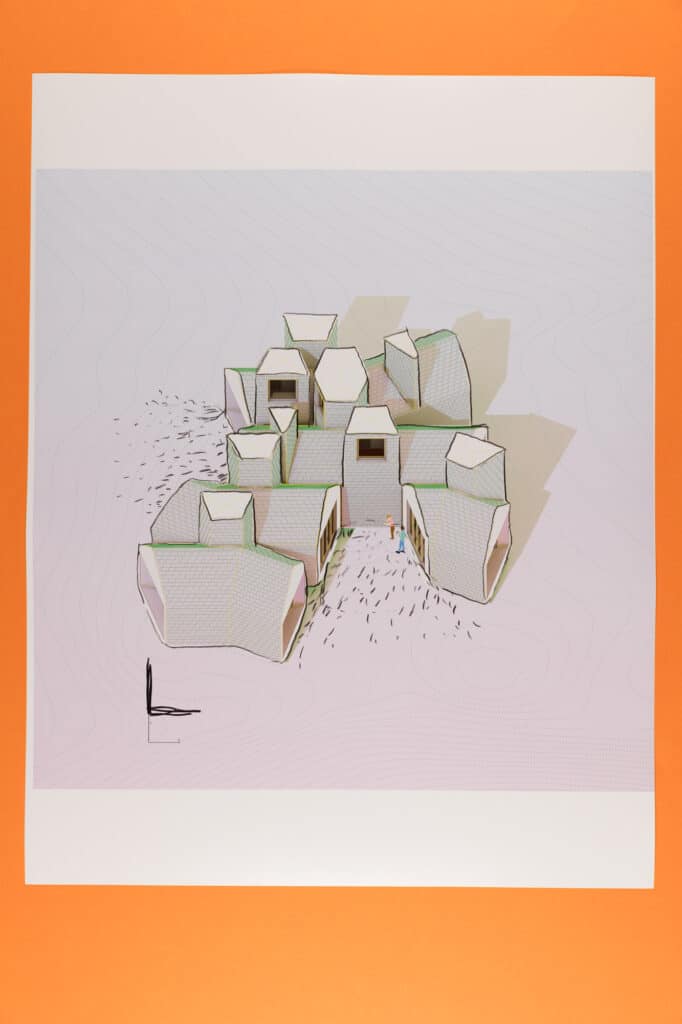

MM: Hopefully our drawings reflect how we work and think. We draw constantly: recently we made a children’s book titled Houses For Sale – it can be read by children and adults, architects and non-architects. We have always done books alongside drawing. Sometimes we make books just for the office; large-format books that have not been published. Three of them were recently acquired by Harvard’s Special Collection. These books and drawings are very important to us, although we make very few. They are vehicles to think about architecture in general and our work in particular. Our representation shifted a few years ago. It’s probably always shifting really, but we started doing drawings that are simpler and quite diagrammatic, more like drawing on a phone.

FG: Is it a sort of looser attitude, do you also employ it when you teach?

MM: We have grown weary of the excessive emphasis on representation as the objective in itself, not a medium for thinking and designing. I feel partially responsible sometimes. In our most recent studios, we are working to shift that situation. Last year, I changed the pedagogy for the foundational course I teach at Princeton so students would be more engaged with the ‘world,’ shifting the weight placed on visualisation and abstraction.

FG: The surge of axonometric?

MM: Yeah, well, we use axonometric, but it has become somewhat cliché. Colour gradients, axonometrics, cute cartoon shapes… As soon as one starts to use CAD software, it is evident just how redundant an axonometric is. For Choisy, it was a form of computation, measurable objectivity, which CAD has made obsolete. Nowadays we might use axonometrics as an efficient way to illustrate a building massing or a video game aesthetic. Perhaps, contemporary axonometrics feel cold and deadpan in reaction to the dramatic expressive use of images that emerged in the 1990s, when a spectacular rendering was all that was needed to command attention – the ‘moneyshot.’ Back then, the answer to all of architecture’s problems were addressed through technical expertise. I think that utopian promise of technology in architecture has evaporated for us.

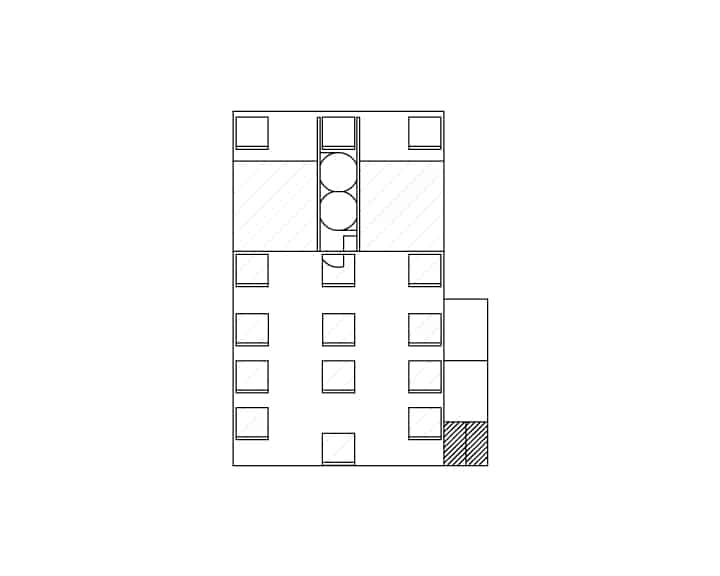

HS: Drawing is a language that allows us to make decisions, to engage with multiple parties, and, ultimately, it is what permits ideas to be translated into construction, thanks to the exchanges around it. Drawings get things built. In the studios I teach at Columbia, the students work in groups to collectively produce a singular and shared three-dimensional digital model of a specific site and condition. We repeat the same site over consecutive semesters, so the file is passed from one cohort of students to the next. In that passage, it is intriguing to see how students manipulate, adapt, and change the original information.

FG: I assume that you have accrued an archive about the neighbourhood, passed on from one course to the next.

HS: Yes, each year the concerns shift, as well as the digital model, which continues to be tweaked and reworked, adding more information. Sometimes it is precise and other times fast. We have been collaborating with the Bronx Documentary Center, a small organisation created in 2011 by the photographer Michael Kamber. The way they document the neighbourhood is extremely relevant to us. Numerous ethical issues are raised about how information is gathered and processed through actions that are much less top-down and abstract than the conventional urban analysis performed in schools of architecture. The exchange was very engaging, and it turned out that numerous students then volunteered for the community garden adjacent to the Center, even during the pandemic. So the dialogue and collaboration went in two ways.

In other circumstances, we created a digital model of Oswald Mathias Ungers project for the IBA in Berlin, which became a centrepiece of the studio. There is an inherent pedagogical value in creating these files. We did not have access to the original drawings for years, so it was an interpretation of what we found in books and magazines. These large digital models become archives of their own; they carry the legacy of the various approaches of the consecutive students who worked on them.

FG: I assume that for your students, seeing how you operate might have had an impact on the ways they deal with the communities that they were assigned to work with.

HS: In the past few years, issues of construction and materials are acquiring more relevance in schools, I think because there is a rising consciousness about issues around climate change, sustainability, public health, and maintenance. Schools cannot be oblivious of reality.

FG: Is this reflected in the assignments given in the studios, perhaps not anymore, a fancy museum at the other end of the world, but as you did in your studios, something closer and tangible?

HS: I think that observation and direct implication in a specific situation are important. We receive students from all over the world, but we want to engage them with New York or in any case with places that can be visited and are within walking distance. I heard someone say recently that architects don’t do field work, which is not true. In fact that might be the only thing that we can do, or might do depending on a project.

MM: In the schools, we ask that notions of material, construction, and building start to be engaged in the drawings even in the first semester. It is a change from what has been the principal assumption of foundational design studios, especially in the United States, where education begins with the abstract, formal, and geometric, and rarely deals with the physical aspects and realities of architecture.

There has been a certain snobbery, as if these matters were proper for a trade school and not a university. There is a class foundation to architecture, and the all too easy abstractions of site, construction, money, environment, materials, labour, people… We want students to work less abstractly, and that requires them to talk to people outside of the school, different people, like clients or inhabitants of architecture. We want them to talk to people more. This helps everyone learn from each other. There’s a retreat in talking only to other architects, or doing all our research through Google, not engaging with others.

FG: How did you translate this attitude into your teaching?

MM: We planned three consecutive projects reflecting what was going on around us. The first was simply for a room for one, taking into account isolation. The second was a house for at least two people. The third was a community centre, and students had to get in touch with a local community, group, or organisation. The communities were very different, sometimes in direct relation with the student’s identity and curiosities, others were associated with specific interests. We also encouraged students to present their projects to everyone they talked to, which was slightly awkward for them. It’s like showing your work to your non-architect relatives, which can be an uncomfortable experience.

FG: Are there ways in the schools to be grounded in reality while shielding the students from too much infiltration by all these constraints of the profession? When does BIM or technology or budgeting enter the design studio without stifling any experimental approach? I remember the moment when architecture students were meant to learn ‘coding.’

MM: Yes, I would rather have students know how to build more than how to draw. Yet, I am ambivalent about how far one should become a truly polytechnic school, like in Spain or at the ETH in Zurich, because the freedom of education and the certain speculative autonomy that has been inherent in US schools is important. Hopefully there are ways to have both aspects.

FG: I find quite revelatory how many interesting practices in the US always keep a position in a university.

HS: It’s true, but the relationship between teaching and one’s private practice has shifted. It is important to underline how rare it is today that the profession hijacks the resources of schools. When I was a student, I remember not being able to use the wood shop to make models because a professor took over the entire shop for a competition. You would have to fight for space, it was uncomfortable. It’s good that things have changed. As a faculty member, I don’t have an office, my work is done in the MOS studio, and my desk has multiple piles around different subjects, they are like little mountains that are constantly moving up and down with new things added or taken away.

FG: You often use the terms ‘reality’ and ‘realism’, why so?

MM: Not sure. We recently reread an exchange between Rem Koolhaas and Cornel West at MoMA in 2000 at what was dubbed the ‘Pragmatism’ conference. Hilary was revisiting this moment for a design studio she taught at Harvard GSD. While Koolhaas advocated for an anti-nationalist neoliberal global ideal, West advocated our need for history, for political discourse, and for action in a specific location. He argued that in the absence of specificity – national identity, local histories – global capitalism takes over. This focus on the local and the rooted is important for us.

This is somewhat unrelated, but recently I was criticised by a friend for our pitched roofs as being ‘postmodern.’ I took it as an insult. In fact, they are not, if you want things to be built within a budget in upstate New York this is just how you do it. We don’t have the luxury of always telling everyone how to build, sometimes you have to work with what’s available.

FG: I read many of your projects also as commentary or a reading of reality – like what you just mentioned about the roofs. Are ‘pragmatism’ and ‘reality’ words to escape from the rarefied jargon of badly digested philosophical thinking that seem to afflict recurrent schools of architecture? We had our doses of Derrida and Deleuze for ages, now it is ‘object-oriented ontology’; I always wonder what good these discourses can do for architecture education.

MM: We are influenced by what other architects have done more than philosophers, I suppose. For one, Lacaton & Vassal comes to my mind. They have been fundamental to rethink our field, to entirely modify numerous attitudes and prejudices, again via a work that is consistent and scrupulously concentrated on reality, frequently a very local one.

HS: Their park in Bordeaux in 1996, where they decided not to design anything and to use the money just for maintenance is a wonderful example for what we are doing now in the design studio at Columbia University. A student of mine from China brought this as her precedent in response to my brief. I was a little bit annoyed that it had already been done – and done so well!

FG: Are you convinced about the importance that several architects attribute to hand-drawing as a fundamental instrument for teaching?

MM: It is an absurd conversation, where one should learn to draft first by hand and only later can move to the computer. It is ridiculous! You just draw with whatever tool you have at hand and feel comfortable with, analogue or digital. Whatever the means, we err on the side of the unfinished, the raw, the incomplete, the playful, as it feels more open to us.

HS: I still think that there is a value in knowing how to use digital technologies, something that seems to be currently questioned. Perhaps mine is an attitude that has to deal with gender because when I started studying architecture there was almost a prejudice that women were not capable of dominating computers and software. There were very macho ideas about technology, and they linger.

MM: We draw constantly, though in a not very rigorous way, any scrap of paper is fine.

FG: Do you encourage your students to do the same?

MM: Not really. Some do, some don’t. It is not really structured in the way we teach. When we studied, sketches were very personal and never of interest to professors, who just expected to see the final representation, ideally precise and perfect. I noticed that today there is a stronger interest by students to generate a recognisable style of drawing, almost as if it were branding.

HS: I would not call it branding, that sounds harsh. It is rather the exploration of a personal voice, not that distant from visual artists.

MM: True. In fact, when I asked some of our younger collaborators what they look at, many said other students’ work, which surprised me. I remember how we were obsessive about what Rem Koolhaas, Herzog and de Meuron, or Steven Holl were doing at that moment, having to wait for magazines to be issued. When I explain that, the response is ‘You really did that? How interesting!’

FG: Does it have to do with the immediacy of how we access information? Even using Google is slower than Instagram, ten seconds perhaps, enough to put off many.

MM: Do you think that it might generate some sort of tribalism in architecture, with competing groups that coalesce on competing Pinterest boards?

FG: Perhaps, with an ever-expanding landscape of sub-genres as in music. On the other hand, I notice a certain eclecticism, where younger architects and students pass through successive phases with a certain levity, a little bit like Pablo Picasso.

HS: This is very good, as it is crucial to try different things, rather than quickly embrace a determined language.

MM: At least in the US, design education can lead to quite diverse trajectories. I think that if you study architecture in Japan or Switzerland, you are determined to become an architect, and therefore you already operate with the local codes of representation that are also to be found later in the profession.

FG: That was patent, for instance at the FAUP in Porto, where students’ presentations were indistinguishable from what architects were submitting to competitions.

MM: In the US, you might study architecture and then end up as a designer at a video game company, set designer in the cinema industry, work at a startup, or get a PhD. I think that this explains the eclecticism we see, needing to be equipped with a variety of skills.

FG: Is this advocating for a different role for architects, through lighter operations?

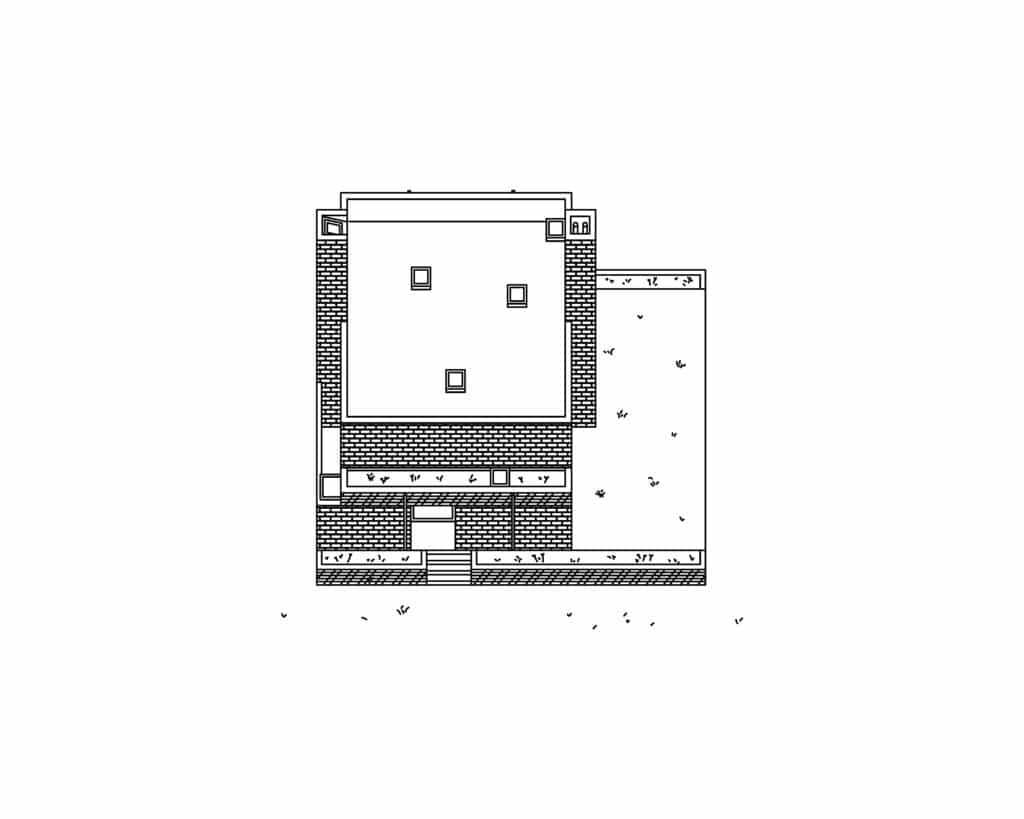

HS: The studio that I teach at Columbia now is titled ‘As little as possible.’ It’s a project to reimagine a public space, it’s called McKenna Square Park, but it’s not a traditional square, nor is it a park. It is actually a very long triangle adjacent to a church, with a few facilities from the ’80s in it. Students are pushed to reimagine the place through quite minimal actions. They need to understand what is removed and what is added, through very careful operations. In the park there were already very subtle actions that impressed a very strong sense of place and were appropriated by the community, and the park was only built because of a contract signed with the neighbourhood. There are many questions it raises about ethics and equality, and the impact of design at a small scale.

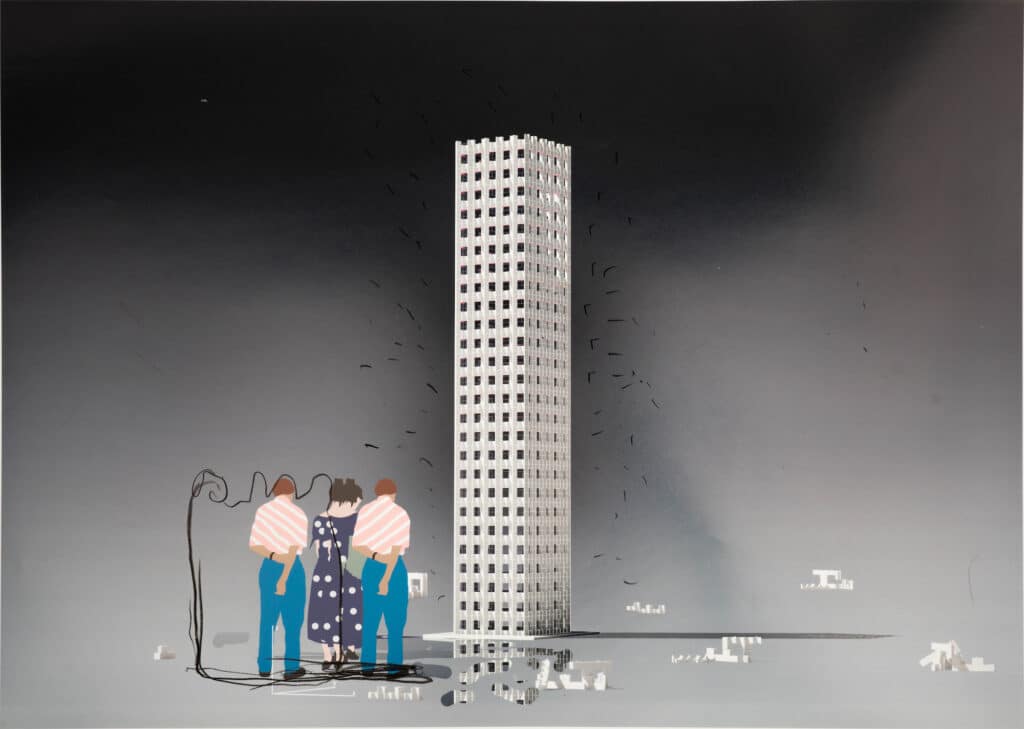

MM: The idea of architects designing expressive spectacles in order to affirm their relevance does not interest us.

HS: Just here in New York, the disaster of the Hudson Yards initiative is a testament to that mood. It is the coda of an era that we hope is over. We need to reformulate what we can do as architects in direct dialogue with communities and not anymore with the abstract figure of financial capital. At the same time, we are very aware that there is an accelerating concentration of power and resources, where new building technologies, especially the ones for larger programs, will be owned by a handful, so that many architects will be absorbed by huge corporate structures and this future raises many concerns.

– Fabrizio Gallanti and Emily Wettstein