L’art tue

L’ART TUE – Art Kills

L’ART TUE was the name of a poster project, most likely between 1975 and 1976. It followed the theoretical and literary Groupe Utopie [Utopia Group] adventure and their publications between 1966 and 1969, and after the Aerolande development work which lasted until 1975. However, it came before the publication of my later theoretical projects, notably those in L’Ivre de Pierres, which began in 1977.

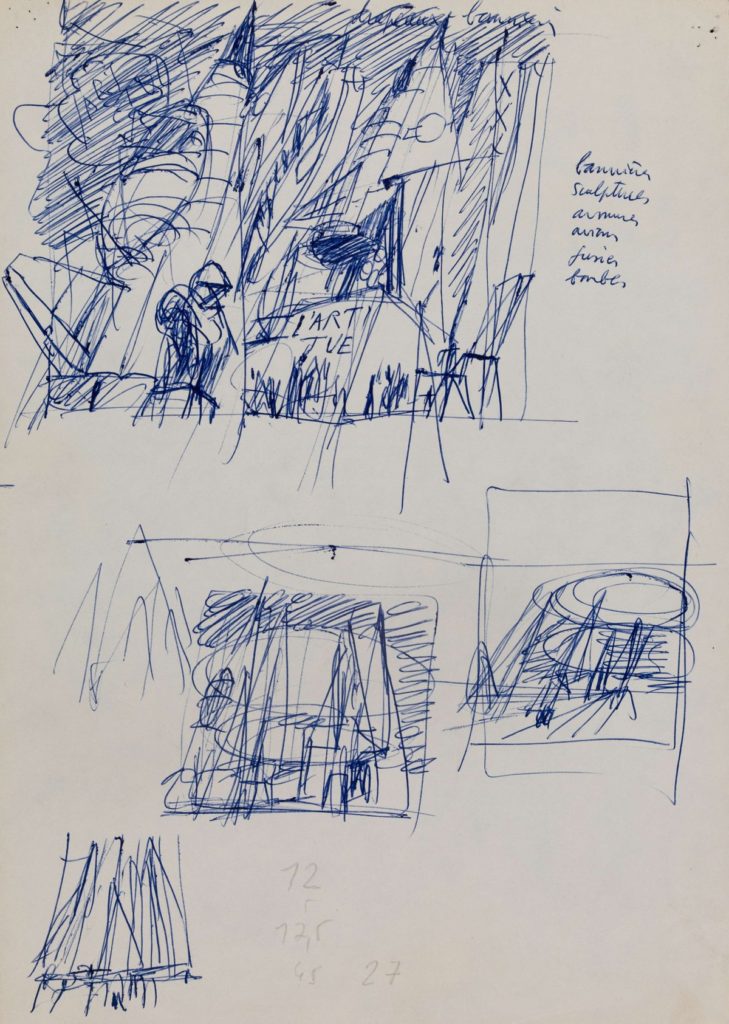

During this transitional period, I asked myself the following question: without going down the usual professional route, which I did not want, how could I fulfil my architectural desires and social criticism? The Free Press, the Anglo-American counterculture, and self-publication ‘do it yourself’ were among the legacies of the 60s and 70s. A media poster could reflect this path, even if the distribution was difficult. My Paris architectural programmes and proposals for festivals were abundant but remained at that time titles, writings and sketches – all intended for later elaboration and publication.

Here was: ‘the desire to write about architecture as you would a story, a novel: with words and images… descriptive writing which tells the story and evokes architectural invention within the narrow atmosphere of a city, Paris’

(Le guide de Paris de L’Ivre de Pierres, 1982).

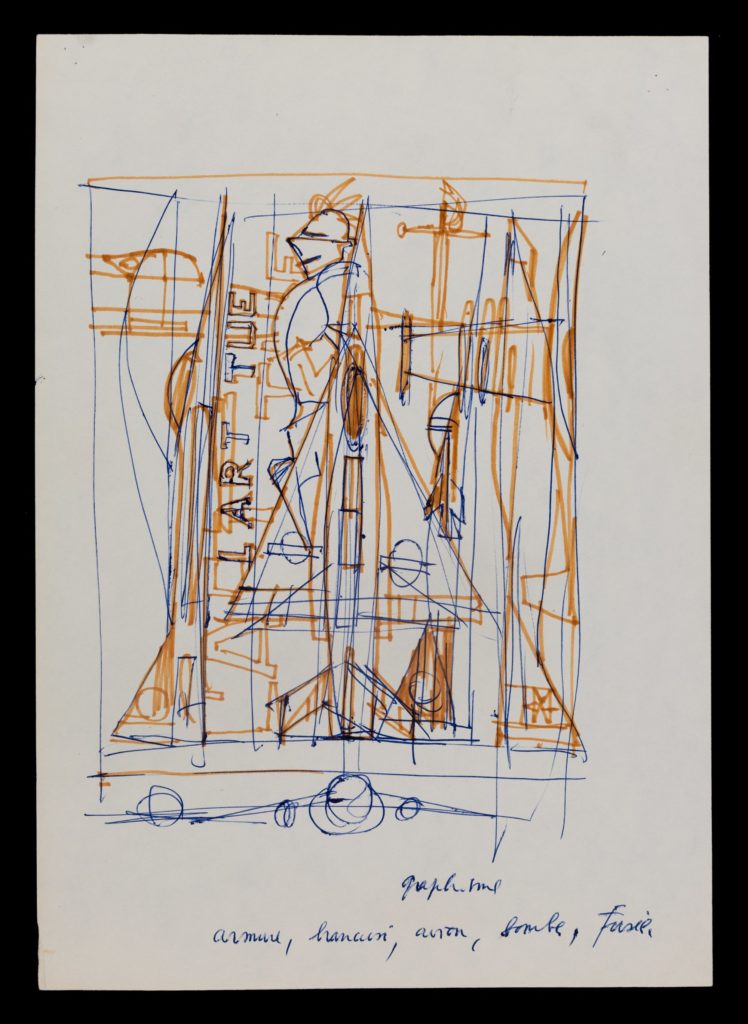

The visual content of L’ART TUE, its references and imagery, cover two topics:

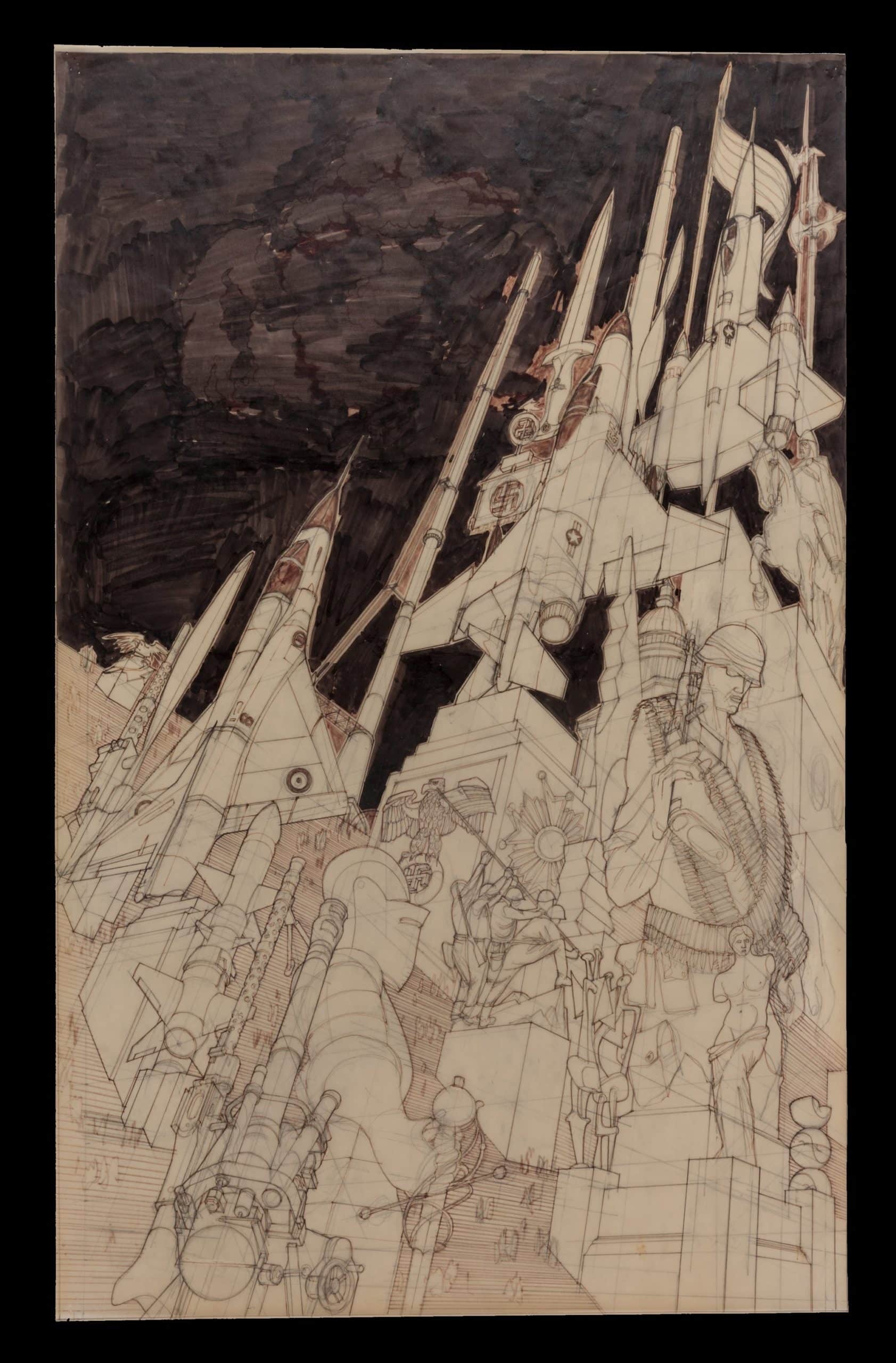

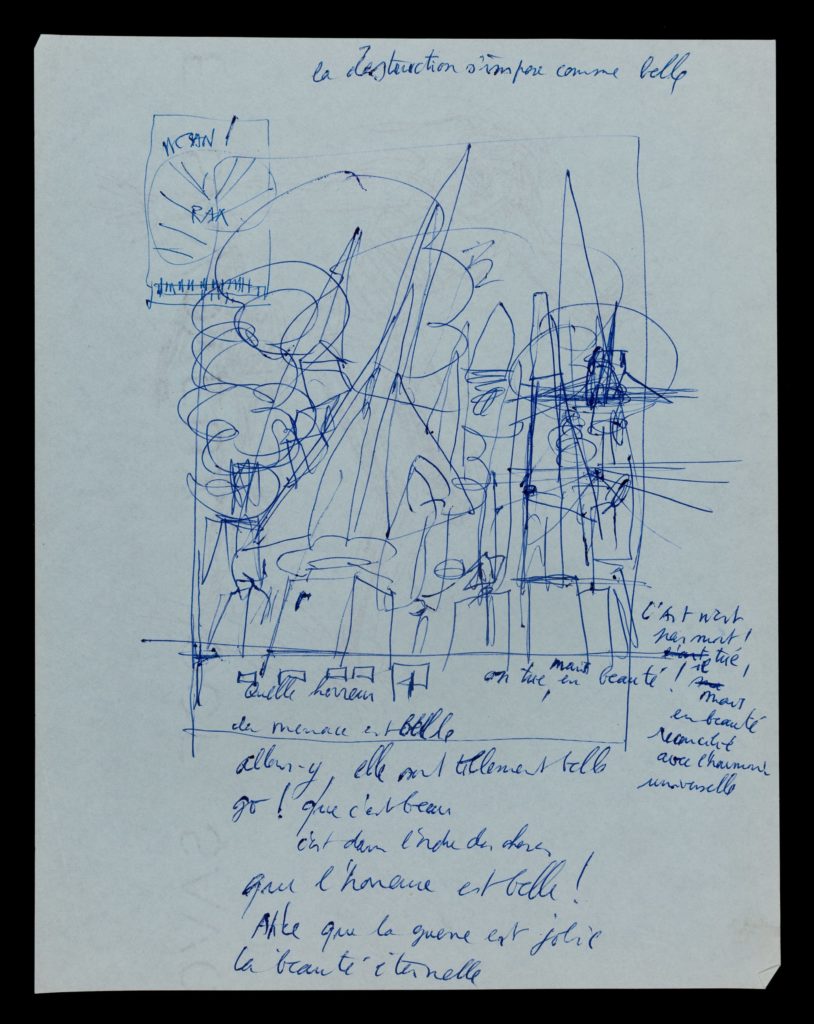

My theoretical certainties and artistic critiques, often elitist and rarely accessible: the seduction and simultaneous distancing effect of a work in which beauty erases reprehension and horror such as the breathtaking design of a combat aeroplane or aircraft carrier (bodies which magnify the beauty of strength and violence), the attraction of war’s wreckage captured on film, or an aesthetic of reconciliation.

But also an invented but undeveloped personal programme: the Esplanade of Art’s Universal Harmonyon the Place des Invalides, i.e. a futurist appearance covering buried surfaces of conflict where the lords of war and the wooing of death are in focus – steel’s black shine, the cold weight of weaponry, the art of despair, Moravagine and the Maginot Line, Vauban’s glacis, spaces dedicated to the conquerors and the powerful and, right at the end, in the axis under the dome of Les Invalides, Napoleon’s magnificent tomb.

This theme returns and is developed in our project La Place de la Concorde – the new shape of a founding square (L’Ivre de Pierres #4, 1983). At the northern end: a symbol of Power is dedicated to the Man of Strength, to the conquerors and the defenders of the law of the jungle. It is a space for winners, for victors.

A short extract from the project: ‘the bronze Atlas, the military Mercedes with stiff flags, an incredible disorder of archangels, sceptres, suns and thrones, statues and equestrian groups, helmets and Amazons, totems, heraldic beasts, predatory fauna, fantastic creatures, blind impulse, the Arctic fox, the ogre, the heroes of glory-carrying knights, divine shamanism, speech, breath, violence… institutional drama, noble, dirty, pure and sacrificial, building a church, discovering a cavern, the brands of demons and those of gods, blind and unknown names on rusting metal stelae, masters whose individuality is lost to history, a recognition of the cult of assassins within a moment.’

Different outlines of layouts and texts preceded this draft, a scalable sketch created as a placeholder for a final product that never came to fruition. The explicit references were always aeroplane cowlings, rockets, armour, Henry Moore, Brâncuși’s smooth bronzes, and post-conflict statuary as well as fascist imagery and decorations: objects whose lure expunges their meaning.