Photo City: How Images Shape the Urban World

A long time before the surge of the Internet and the diffusion of portable devices connected to it, seeping into our eyes incessant flows of images, the relationship of people to their surroundings was profoundly altered by photography, and then cinema. The carefully curated exhibition Photo City: How Images Shape the Urban World at the V&A Dundee, until the 27th of October 2024, is exemplary in the clarity of its intentions and, as a consequence, in the legibility of the content provided to the visitors, and in the pleasure of the experience as well. The curators seem to rightly assume that while we exist in a specific place—in the case of the exhibition mostly urban—our appreciation of the direct reality around us is also influenced and mediated by the baggage of pictures, visual fragments, movie scenes, and sometimes unconscious mnemonic phantasms, that our memories carry. The opening statement of the exhibition is acutely simple and effective:

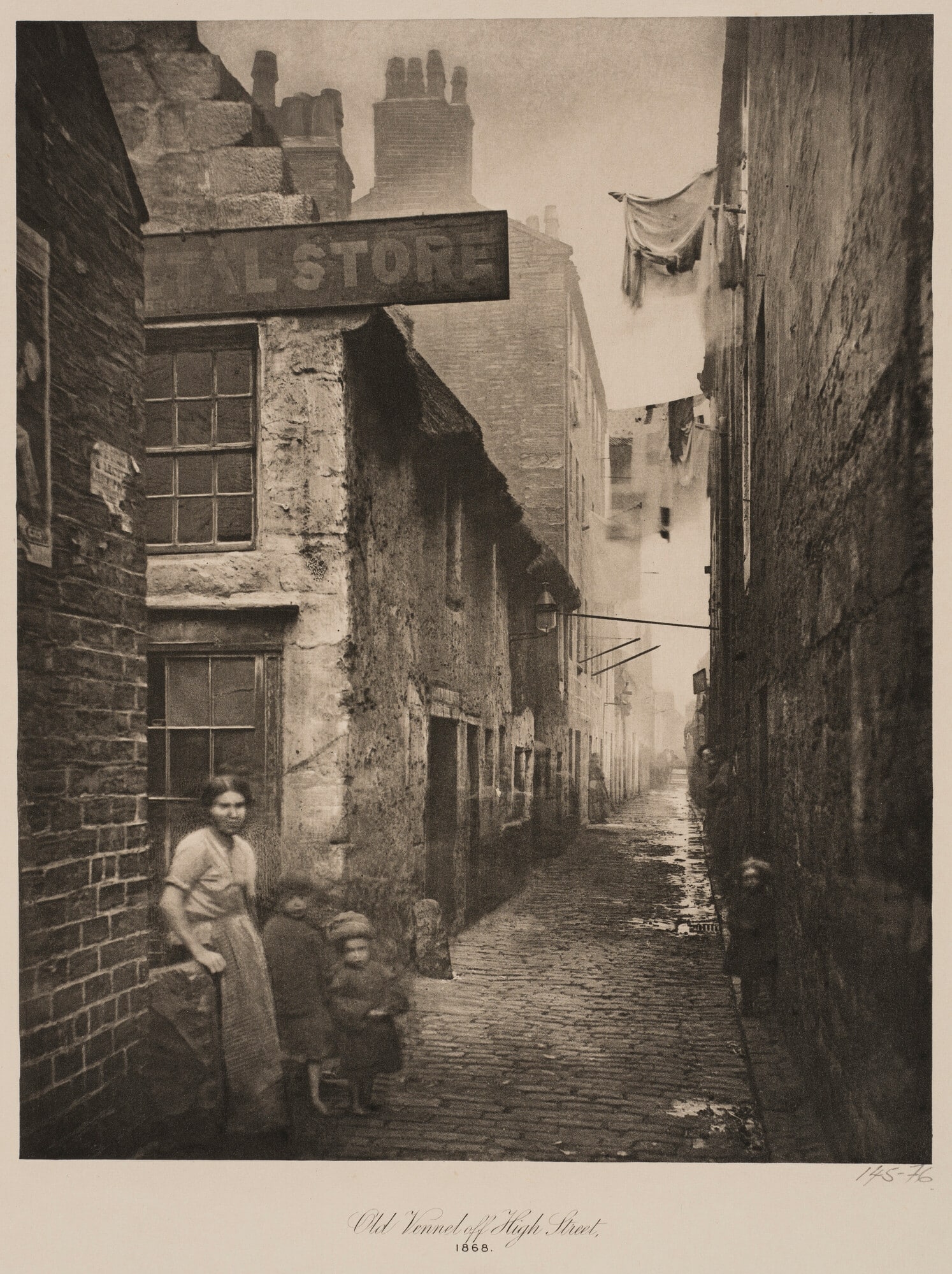

‘The explosion of photographic experimentation in the mid-19th century coincided with the rapid growth of cities across the globe. This exhibition brings together iconic images from the V&A’s collections as well as works by contemporary photographers, architects and digital artists to explore how photography and cities have influenced each other. […] Photography does more than document and reflect city life, it shapes our understanding of cities and helps us imagine future ways of living together.’[1]

Resorting to the vast collections of the V&A in London, and refreshingly deciding to be slightly conservative through a chronological narrative, the curatorial team—composed of Meredith More, Francesca Bibby from the V&A Dundee and Brendan Cormier, Lisa Springer from the V&A South Kensington—has deployed a sequence of artefacts and pictures that accompanies the public in a carefully crafted pedagogical journey: from the early daguerreotypes and stereometric photographic explorations towards more recent experimentations with AI and virtual realities. A successful exhibition should feel like a Gesamtkunstwerk, where content, scenography, lighting, texts and captions, and in this case also an audio-guide activated by QR codes (as it is now the fashion) are perfectly intertwined. The aluminium scaffolding system—designed by the studio SOUP—never gets in the way of the appreciation of the exhibits. The system creates multiple transparencies and diagonal views so that even if the parkour stays strictly determined in its linearity, the visual overlapping of sometimes contrasting components makes one feel as in the urban realm. Avoiding solid walls and playing with enlargements on wallpapers and projections generates an ambient consistent with the narrative. While appreciating a specific item, the peripheral view of the visitor always intercepts other material that will be seen later or that was missed earlier, therefore immersing one in a rather enticing state of anticipation. I observed the public roaming back and forth, slowing down their pace, having conversations about one image, stopping to photograph photographs and just not sheepishly following a path as in many blockbuster exhibitions.

The exhibition begins with the invention of photography, incarnated by a daguerreotype of Saint Paul’s Cathedral from 1840, before immediately taking a surprise turn to focus on aerial photography. The combination of the two inventions, ballooning and photography, creates another way of seeing, providing people with a novel imaginary for understanding their context. This initial cluster reveals the cunning strategy of the curators: sub-topics are introduced, such as the usage of aerial photography for destruction (as aerial photography has been used for reconnaissance missions before bombardments); the development of aerial surveys after World War I as an apparatus at the service of urban planning; material from commercial studios and corporations is juxtaposed with the work of renowned artists such as Margaret Bourke White or László Moholy-Nagy; contemporary content such as satellite imagery is used to prove certain permanence through time. The curators allow themselves the freedom of the notorious Borgesian list, generating clusters that are incongruous in their categorization. One can be about a methodology, such as inventory and survey, mixing Atget, Berenice Abbott, Ed Ruscha, Kevin Lynch and Google Streetview, followed by one about a classic photographic genre, street photography, to then arrive at a larger grouping where photography gets mobilized for social advocacy. Within that cluster, one better understands that Photo City is not a photographic exhibition, where only an endless procession of framed pictures would be on display, but a complex discourse, showcasing the influence and usages of other media for its dissemination, where, Jane Jacobs, Christopher Alexander, the Smithsons or the anti-Apartheid campaigns are thrown into the mix. This complexity is to be found throughout the whole exhibition, where posters, magazines, books, newspapers, leaflets, objects—often cameras or lenses—and videos punctuate the narrative. The exhibition doesn’t skew controversial questions, dedicating one cluster to surveillance and another to the marketing of urban destinations through the creation of icons—ingeniously going back to Édouard Baldus and the French Commission des Monuments of 1858. By coming full circle on its initial premise, the exhibition ends with a section about the proliferation of images across the urban realm, where one happily re-encounters some usual suspects such as Learning from Las Vegas as well as one about the dissolving of the physical city within the digital realm, accelerated during the years of Covid-19.

The show is exemplary—and absolutely worth the trip to Dundee (as is the three-Michelin star restaurant). It is sophisticated without falling into esoteric concepts and jargon; instead, it provides accurate and intelligible information. It achieves the right balance between content that might be already quite known and numerous discoveries and rare finds. The display is perfectly well calibrated in terms of space and timing—you don’t feel it in your joints. It also, of course, generates some envy, because having the V&A as a source is a luxury that many curators dream of. Ultimately, it does what it promises: leaving the exhibition, new pictures that one did not know before keep reverberating in one’s brain, and thus modifying, once again, how we sense the city. Or perhaps the ‘photo city.’

Note

- Photo City: How Images Shape the Urban World, V&A Dundee <https://www.vam.ac.uk/dundee/whatson/exhibitions/photo-city> [accessed 18 September 2024].

Fabrizio Gallanti is a curator and architect with experience in architectural design, education, publications and exhibitions. He is the director of arc en rêve – centre d’architecture in Bordeaux (2021).

– Denise Scott Brown