Le Corbusier, Album Punjab, 1951

The following text first appeared in Maristella Casciato, Le Corbusier Album Punjab, 1951 (Zurich: Lars Müller Publications, 2024), 17–21.

*

Le Corbusier embarked on his first visit to the Indian state of Punjab in 1951 in anticipation of the planning and construction of Chandigarh. Included in his luggage was a notebook, which he would use to record his first impressions of the local culture and environment and document his first ideas for the modern city. This notebook has now been transcribed, translated, and contextualised.

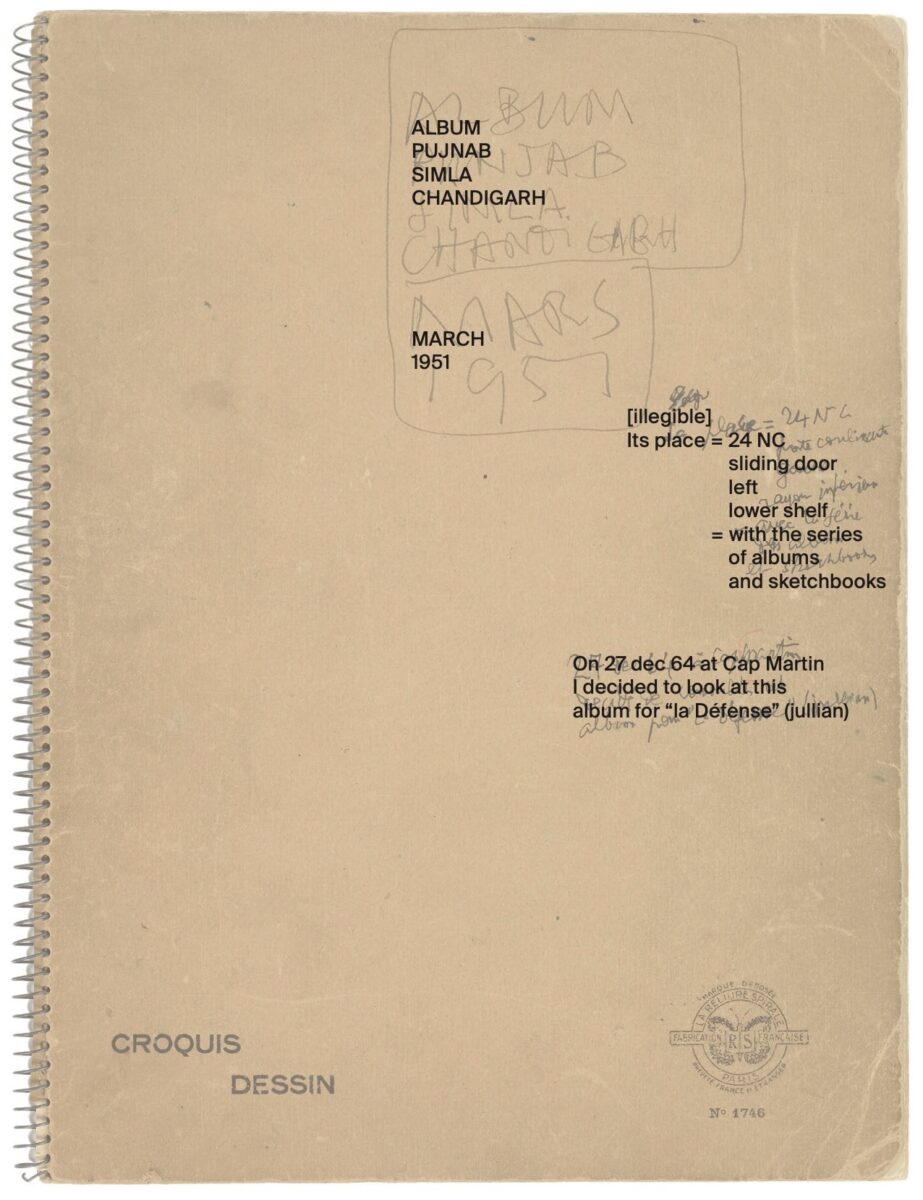

Front cover. Below the hand-printed title of the Album Punjab, there are two notes. The first gives the shelf location that Le Corbusier assigned to the notebook for placement in the library of his studio-apartment at 24, rue Nungesser-et-Coli in Paris. The second indicates that on December 27, 1964, while being in Cap Martin, he consulted the notebook in connection with the building of the Parisian business district of La Défense; the name ‘Jullian’ follows in parentheses.[1] This seems to suggest that Le Corbusier had thought the Album Punjab contained motifs well suited to the development program for La Défense, and may have discussed them with Guillermo Jullian de la Fuente (1931–2008), a Chilean architect who at the time was one of Le Corbusier’s closest collaborators. The project for La Défense was launched at the end of the 1950s; the first tall building, the Esso Tower, was completed in 1963; and by 1964, the approval process for a comprehensive plan for the area was underway. Le Corbusier was certainly familiar with it. So when he wrote that note, he may have been unhappy that he had not been consulted, since there were clearly discernible analogies between the new capitol complex at Chandigarh in its urban context and La Défense in relation to Metropolitan Paris.[2]

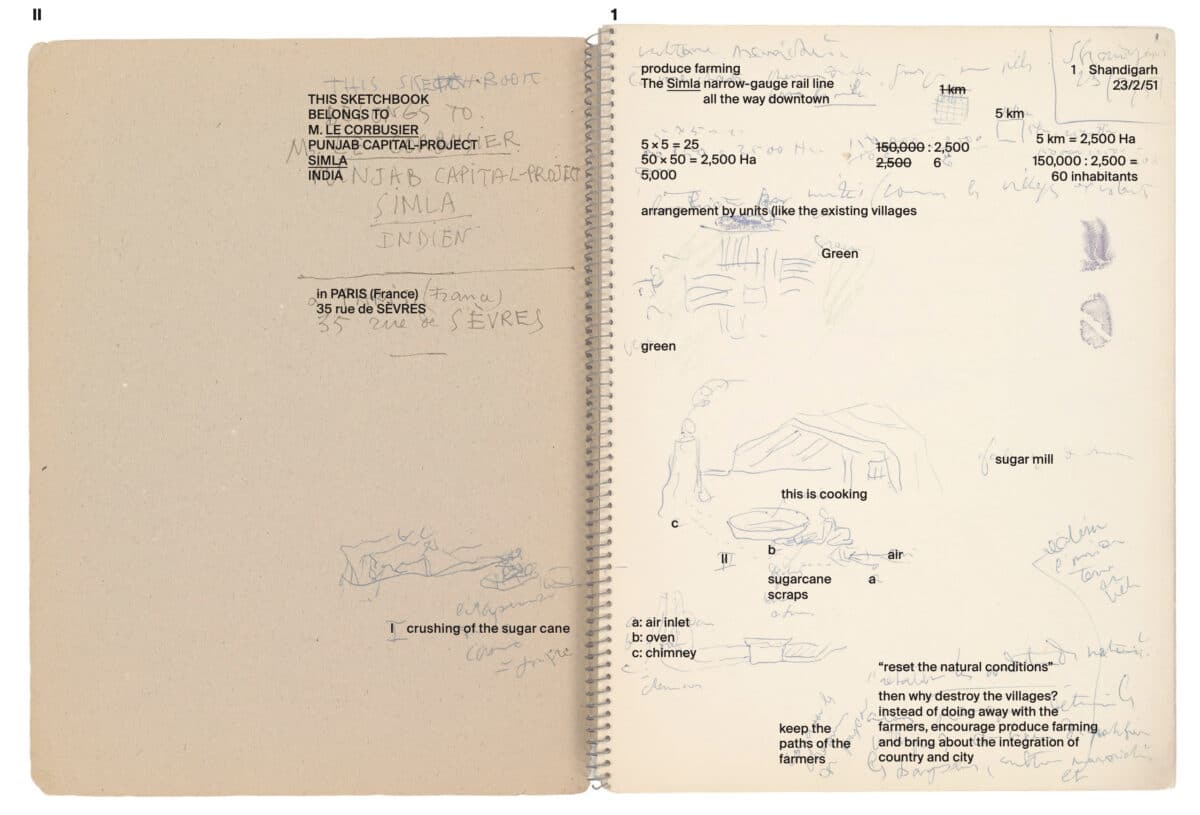

An inscription on the inside of the front cover identifies Le Corbusier as the owner of the album, adding the address of his office in Paris at 35, rue de Sèvres. His use of English (‘This sketchbook belongs to’) suggests that he wrote this in India as a safeguard in case the notebook was lost.

Friday, February 23, 1951. On the first page of the Album Punjab, the recto of the first sheet, Le Corbusier began to make notes and drawings for the project page 1. The first day of work at the site involved a tour through the surrounding countryside, travelling by jeep, and an afternoon meeting with P. N. Thapar. It was a Friday. The date is given in the upper right-hand corner, below the phonetically spelt toponym ‘Shandigarh’–a misspelling that probably reveals how Le Corbusier pronounced the name of the new city.

Roughly a third of the way down the page, on the right-hand side, appears the impression of the rubber stamp Le Corbusier designed to identify the documents related to his master plan for Chandigarh; above it is the smudge of a failed first attempt. This mark, which also appears on the last written page of the album, is the first in a series of 23 different stamps–one corresponding to each of his travels to India–that he designed and carved on erasers.[3] It is very likely that the sheets of the Album Punjab were stamped by Le Corbusier after his return to Paris.

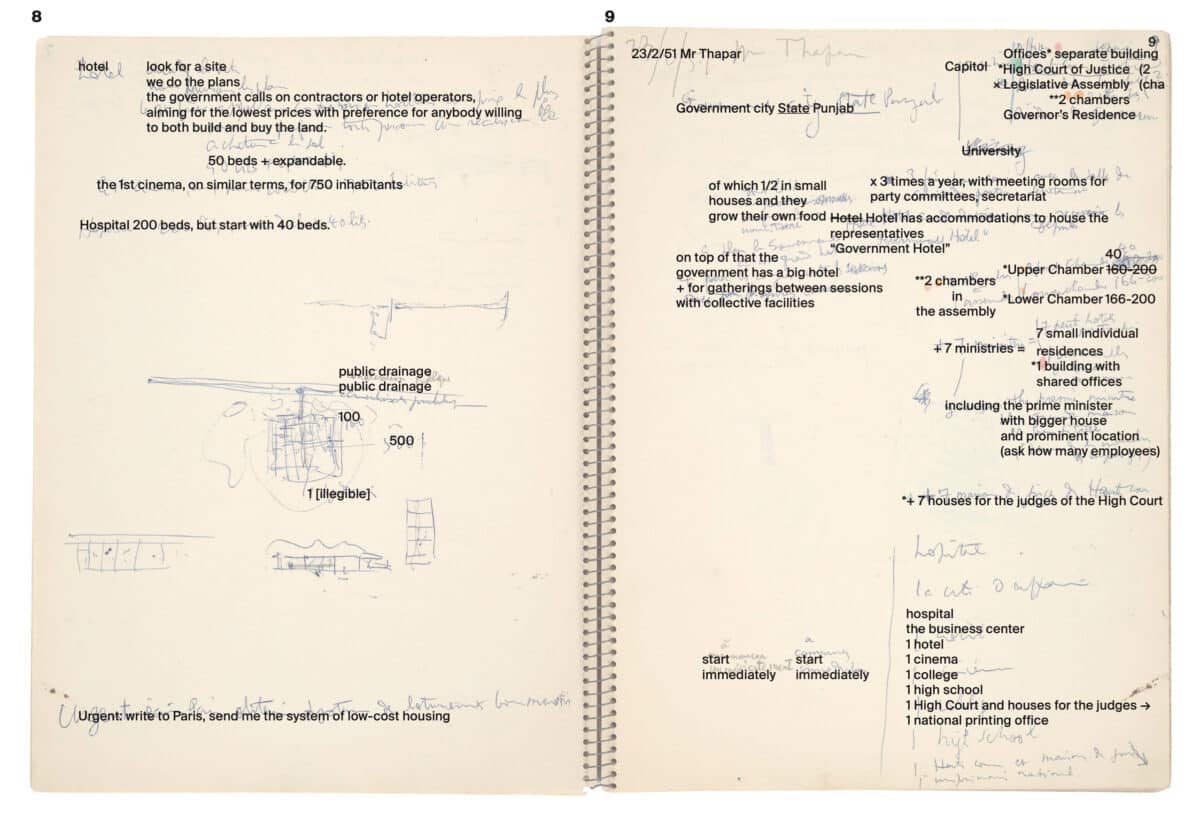

Since the first 9 sheets of the album, 13 individual pages, pages 1–18, were filled literally the day after his evening arrival at the site of the new capital, before the next date appeared, the notes and sketches inscribed on them presumably refer to activities and meetings that all took place on that first day. Le Corbusier’s notes were rapidly written, their contents were summaries; he no doubt jotted them down as the group travelled from one location to another.

Several of these sheets are devoted to Le Corbusier’s observations during the initial inspection of the plain where Chandigarh would be built, a tour led by engineer P. L. Varma and one of his assistants. One of the first sketches records activity at a traditional sugar mill, page 1, a rustic yet ingenious device that particularly interested Le Corbusier, evincing the intensity of his curiosity and respect for those who devised and operated it. As he took in more details of the scene, his drawing marked I, which he started on the inside of the front cover, spilled over into the first sheet in an almost cinematic way.

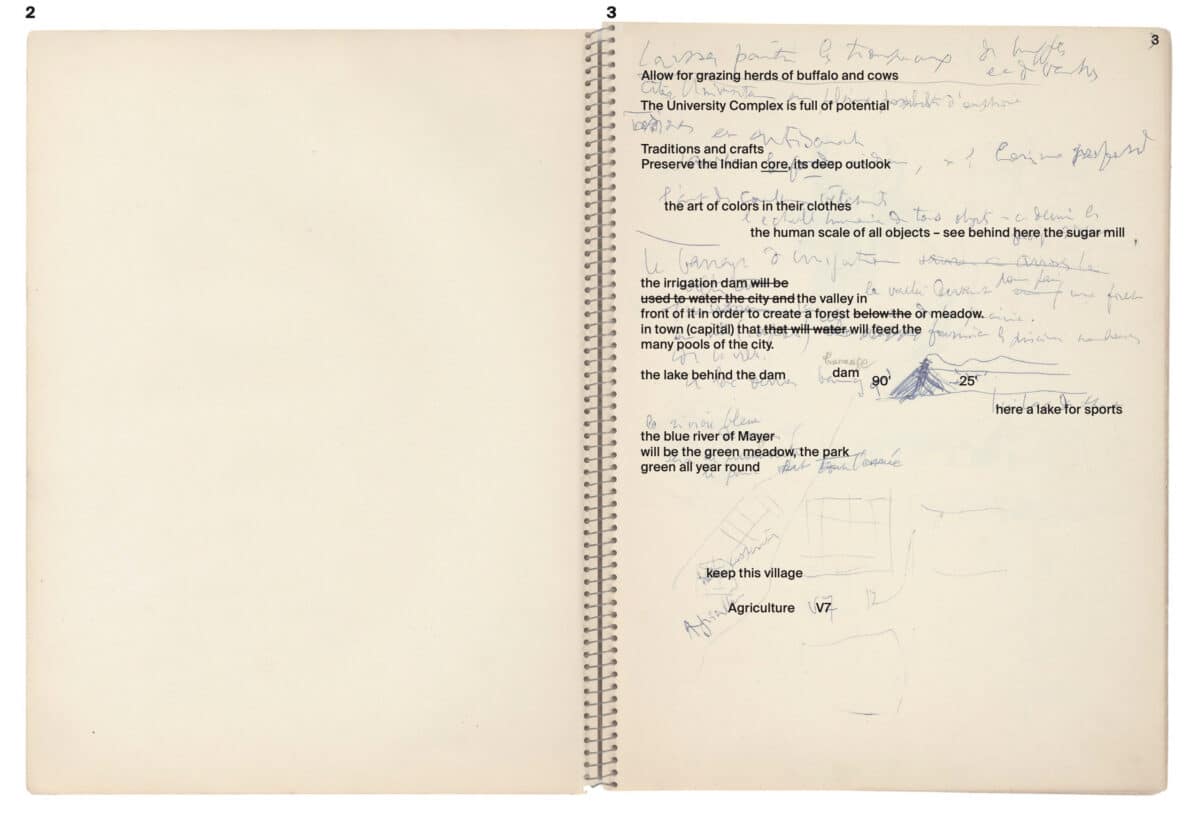

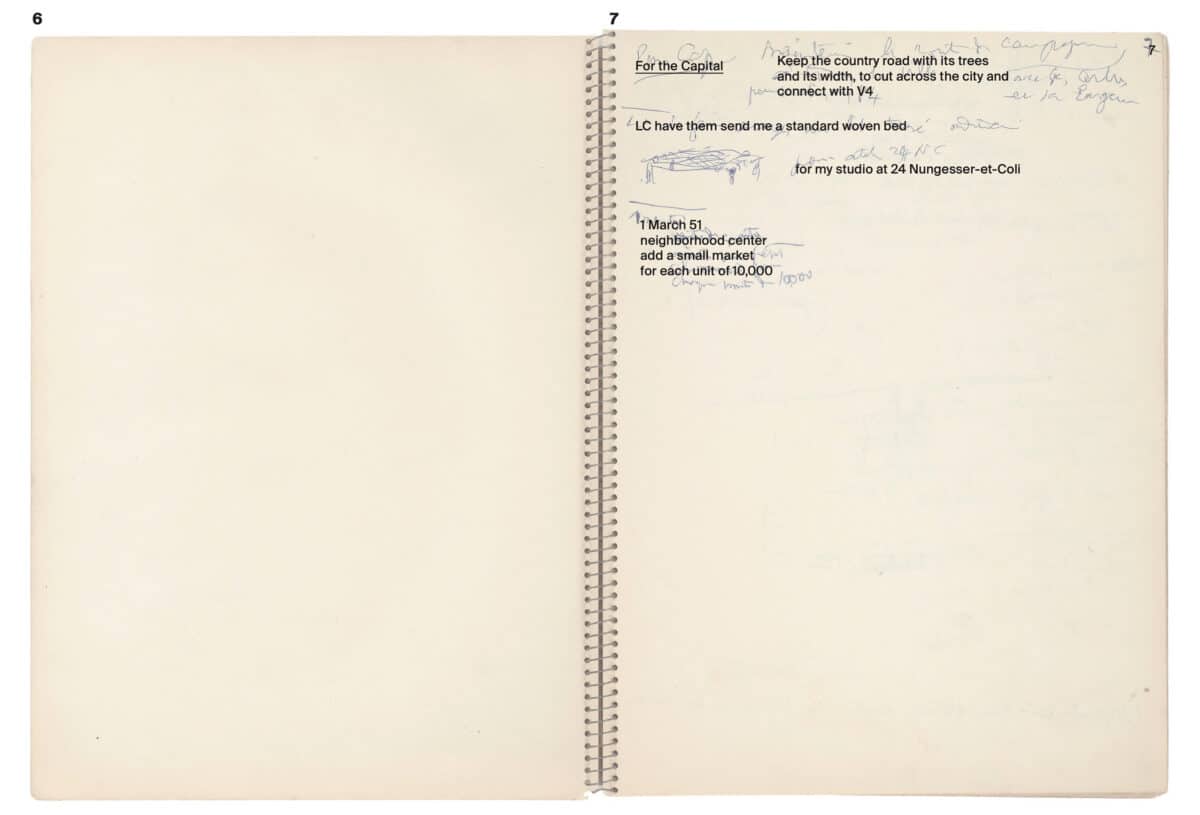

Here, Le Corbusier also noted his initial thoughts about the population density of the future city, planned to accommodate 150,000 inhabitants organised in ‘units like the existing villages.’ This suggests his desire early on for the plan to be commensurate with the scale and density of the traditional villages. He even questioned the logic of dismantling them, writing ‘reset the natural conditions,’ perhaps quoting something that came up in conversation, followed by ‘then why destroy the villages? Instead of doing away with the farmers, encourage produce farming, and bring about the integration of country and city.’ He noted to one side, ‘keep the paths of the farmers.’ On this and the following pages, his reflections are echoed in notes like ‘keep this village’ and ‘Agriculture’ page 3, and ‘For the Capital / keep the country road with its trees and its width, to cut across the city and connect with V4’ page 7, prefiguring his concept for the road system for Chandigarh.

The drawings and notes on some of the sheets record Le Corbusier’s reaction to particular aspects of daily life in the villages he visited. The natural simplicity he discovered in these places impressed him greatly. He was intrigued by the furnishings of the houses, like the charpai, a traditional bed made of woven natural-fibre ropes stretched over a wooden frame, which he sketched on page 7, adding a note to remind himself to have one sent to his studio-apartment in Paris, at 24, rue Nungesser-et-Coli.

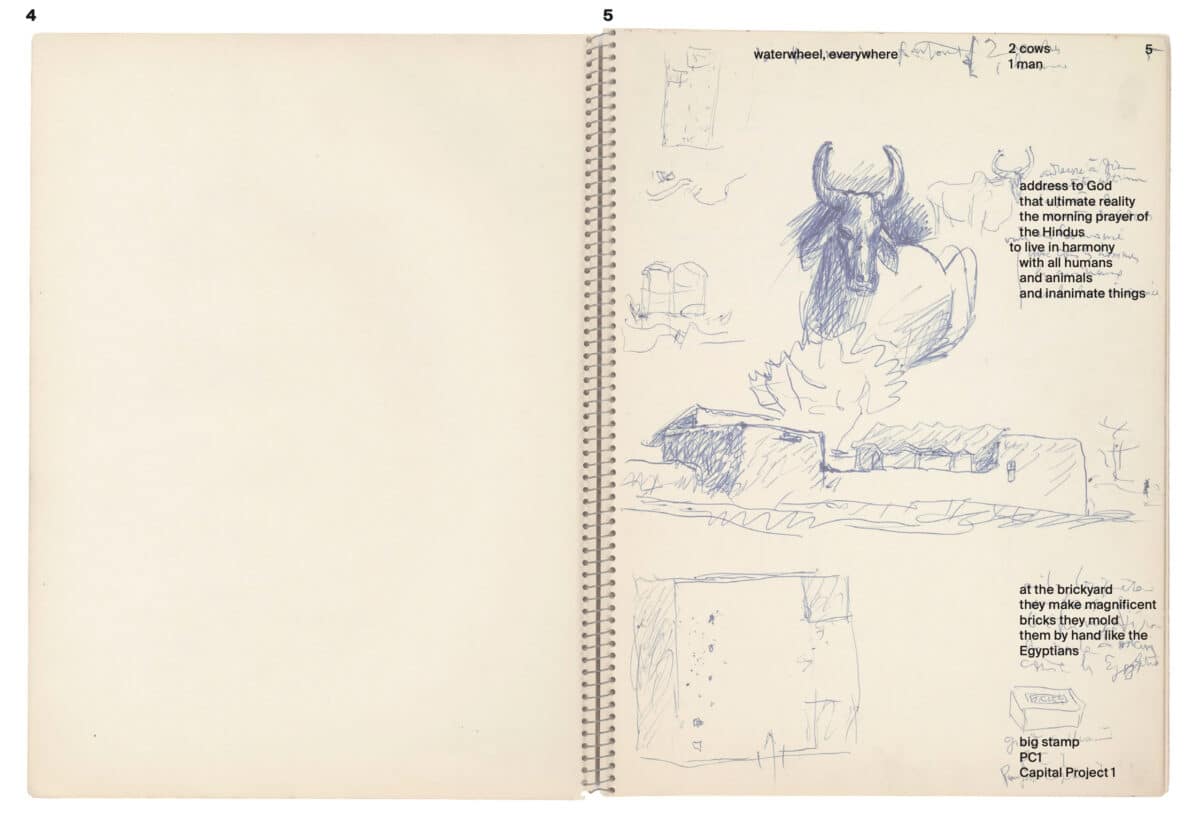

Other observations on these early sheets concern the urgent need to construct an irrigation dam to ensure the city’s water supply, to control the temperature of the air page 3, to ‘allow for grazing herds of buffalo and cows,’ and later to create a lake for leisure activities.[4] At a brickyard, he admired the craftsmanship of the bricks made by the local inhabitants, who ‘mold them by hand like the Egyptians.’ To prefigure the same fine work being applied to the making of the bricks for the future capital’s buildings, he envisioned all of them marked with a ‘big stamp / PC1, Project Capital 1’. The project actually came to be known as the Punjab Capital Project (PCP).

The name of the American urbanist Albert Mayer, who designed the initial master plan for Chandigarh in the years 1948–1950, is invoked for the first time in the Album Punjab where Le Corbusier wrote page 3, ‘The blue river of Mayer will be the green meadow, the park / green all year round,’ suggesting the very different ways the two planners envisioned separating the capitol complex from the urban fabric: Mayer’s shallow water basins and Le Corbusier’s green space with a canal – neither of which was ever realised page 33, below.[5]

Le Corbusier made notes during the very first meeting with P. N. Thapar, who had travelled south from Simla to brief the architects on various key functions that the master plan would need to address page 9.[6] These notes are divided into two parts on the page. Above, Le Corbusier recorded a list of requirements related to Chandigarh’s role as the seat of the Punjabi state government. Below, he listed a set of facilities ‘to be started immediately’–hotels, schools, and hospitals–in order to provide essential services to the population as well as residences for judges of the Supreme Court serving several Indian states. The judges, who belonged to the apex of society, were to have the option to live in houses designed by the Architects’ Office and built at their own expense.

Notes

- Cap Martin, in southern France, is the location of Le Corbusier’s Cabanon de vacances, a cabin of wood logs he built as an exclusive retreat for his wife, Yvonne Gallis, in 1951. It is worth noting that the album was held in Paris; therefore, this means that what was happening at La Défense was creating so much stress for Le Corbusier that he took the album with him, aiming to look it up at his vacation home.

- Norma Evenson commented on the major transformations of Paris in the 1950s as follows: ‘Poor Le Corbusier. No wonder he was bitter. Everyone got a chance to build Le Corbusier’s city but Le Corbusier himself,’ in Yesterday’s City of Tomorrow Today, ed. H. Allen Brooks, Le Corbusier (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987), p. 245. Also to be noted is that in April of the same year, 1964, Le Corbusier travelled to Chandigarh for the inauguration of the last large building of the capitol complex, the palace of assembly. This would be his twenty-third and final voyage to India.

- The series of stamps came to be called Voyages Chandigarh / Calendrier des signes (Chandigarh Travels / Datebook of Stamps). Using them, Le Corbusier organised a visual classification of the gargantuan number of documents produced for the new capital over a period of approximately thirteen years. I thank Arnaud Dercelles, head of the Resource Centre at the Fondation Le Corbusier in Paris, for sharing with me these details. He wrote in a letter dated November 2022: ‘From February 21, 1951, to May 2, 1964, Le Corbusier made twenty-three trips to India. . . . In order to mark drawings and plans he created a series of stamps. . . . Each trip to Chandigarh had an eraser stamp to mark the trip, which allowed him to order these drawings according to his movements. These stamps were erasers that he sculpted himself, borrowing geometric, organic forms. . . . Some stamps representing a sun . . . a building strongly resembling the Chapel of Ronchamp, and so on.’

- Sukhna Lake, a reservoir northeast of Chandigarh, which was constructed by damming the Sukhna Choe, a seasonal stream that flows down from the Shivalik Hills.

- Here the reference is to the fact that the construction of the dam would imply the displacement of the initial location of the capitol complex as foreseen in Mayer’s plan.

- See the detailed letter Le Corbusier sent to his wife, Yvonne Gallis, February 25, 1951, in which he mentioned that the team spent the afternoon with P. N. Thapar, informing her about his return in two days, in Le Corbusier Correspon- dance, Lettres à la famille, 1947–1975, vol. 3, eds. Rémi Baudouï and Arnaud Dercelles (Paris: Fondation Le Corbusier and Gollion, 2016), 165. Le Corbusier took to calling P. N. Thapar ‘ministre’ given his political role in the Punjabi government; he characterised Thapar as un homme de grande classe, a first-class gentleman. Regarding the architects’ team first encounter with Thapar making a presentation in English and Le Corbusier sketching and writing in response, there a few pages of drawings by his cousin Pierre Jeanneret that reveal the fact that Jeanneret was grasping Thapar’s meaning without knowing English, directly through the drawings Le Corbusier was making in the Album Punjab; see Sketches and Notes, 1940–1965, ARCH268391, Fonds Pierre Jeanneret, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret.

Maristella Casciato is Senior Curator and Head of Architecture Special Collections at the Getty Reseach Institute in Los Angeles.