A Machine is a House for Making a Living

‘Mobility’ has long been a theme in architecture. After observing everyday life in Chinese cities, we became interested in exploring an understanding of mobility, which is not primarily defined by motion, but by the practices of pausing and occupying urban space.

The discovery comes from the vehicles used by street vendors, which we consider a type of machine—both because of their original mass-produced nature and how vendors transform them into working tools in daily life. Tricycles and four-wheeled vans are often modified with all kinds of materials by vendors who cannot afford shop rents. Without licences, they must keep moving, temporarily setting up food stalls, barbershops, fruit stands, and more. Their wheels act as camouflage, making them seem transient—even when they remain in place. Authorities often overlook them as permanent structures. In this way, vendors quietly claim space in the city, as if they own a real shop. These vehicles blur the line between mobile and fixed, forming a type of improvised, adaptable architecture.

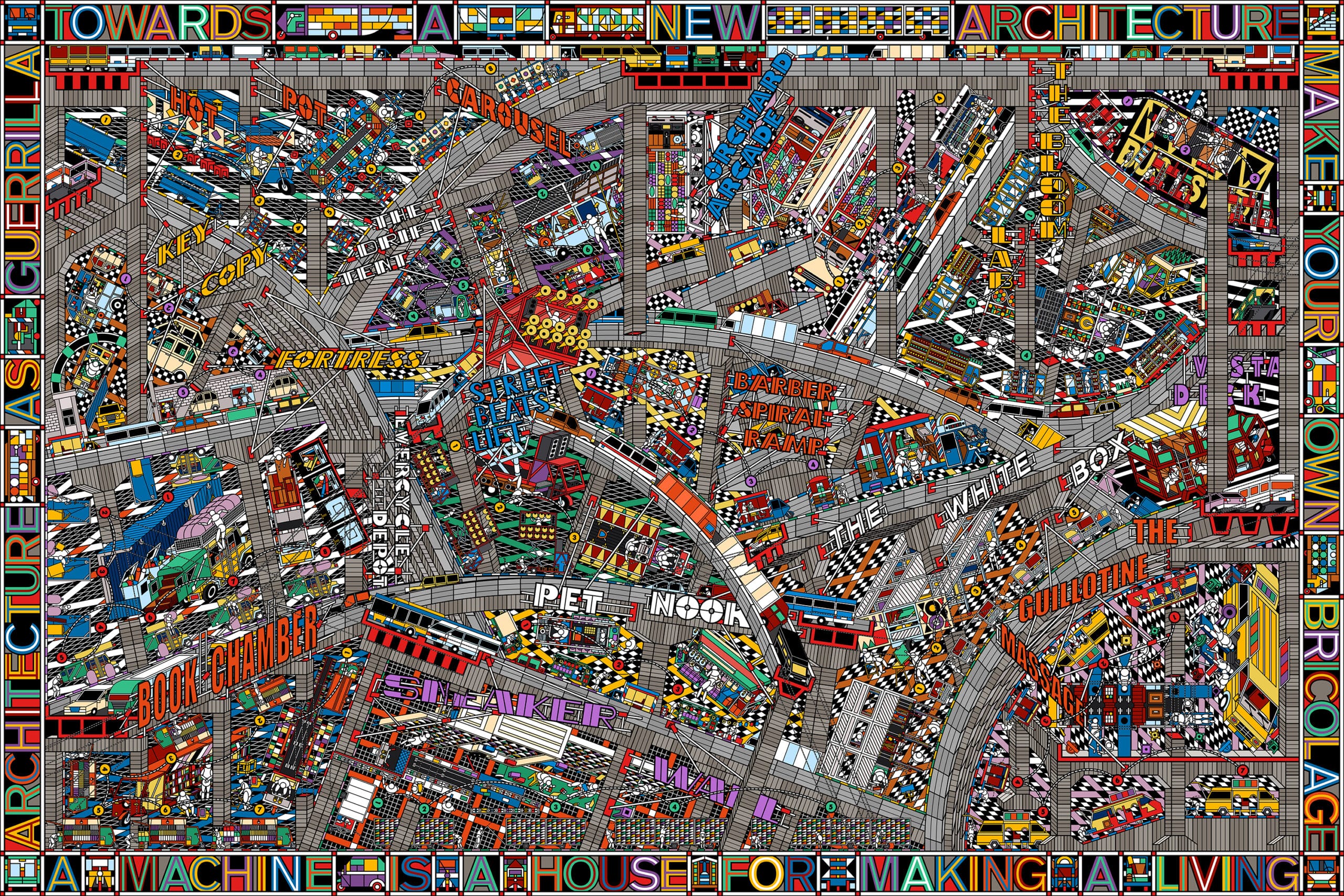

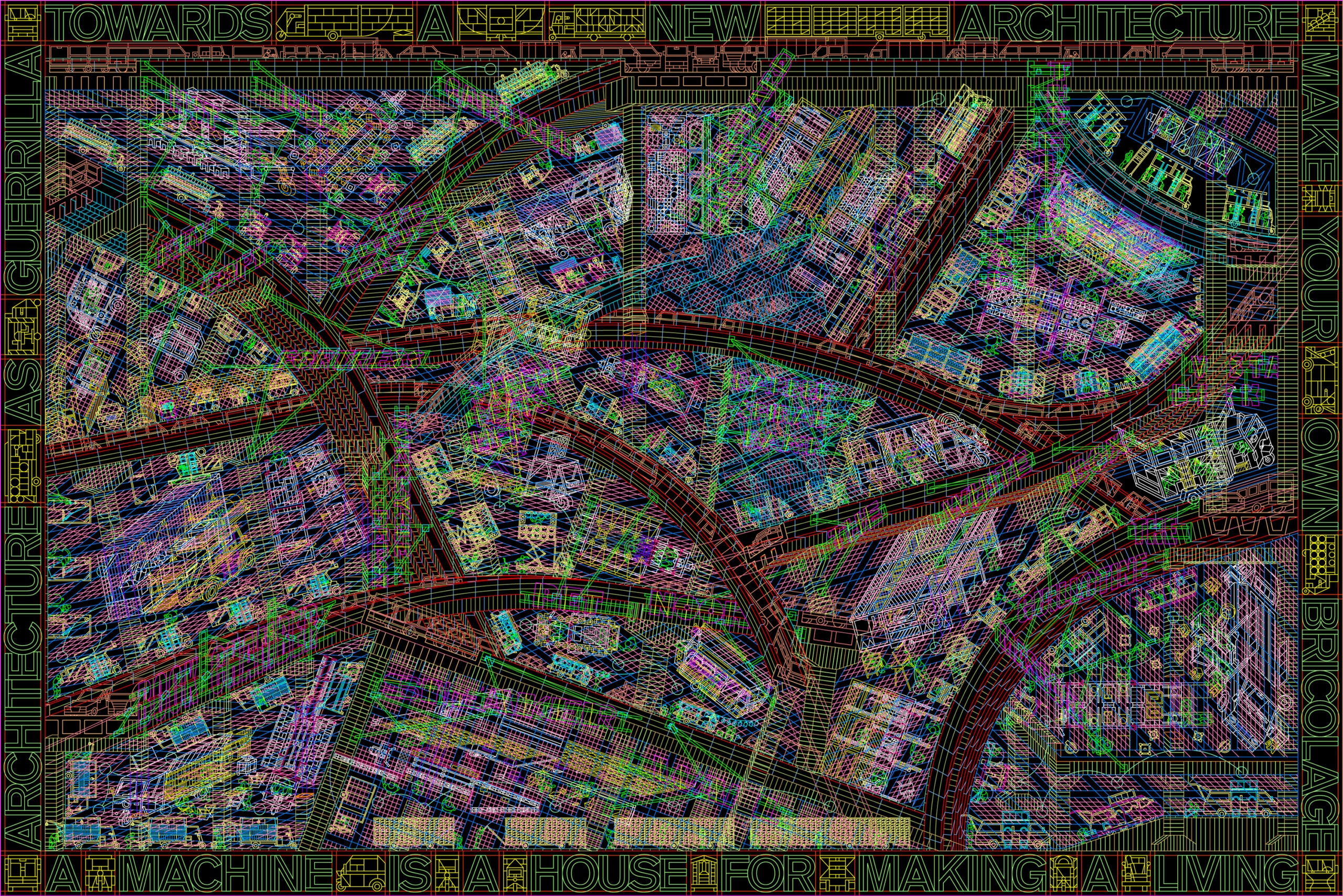

In our panoramic drawing A Machine Is a House for Making a Living, we used a hybrid language of architectural projections to show how such vehicles operate within urban space. Some of the designs are faithful records of reality, while others involve a degree of interpretation and exaggeration. The title echoes—and reverses—Le Corbusier’s famous claim: ‘A house is a machine for living in.’ While his statement connects architecture to mechanical efficiency, our piece shows the reverse: machines—these vehicles—become houses, shaped by everyday survival and ingenuity.

What began as an exploration of this conceptual reversal soon led us to a different kind of reflection—on the meaning of drawing itself in the age of AI. Today, it is easy to generate images instantly using a few prompts. So why spend three months making a drawing like this?

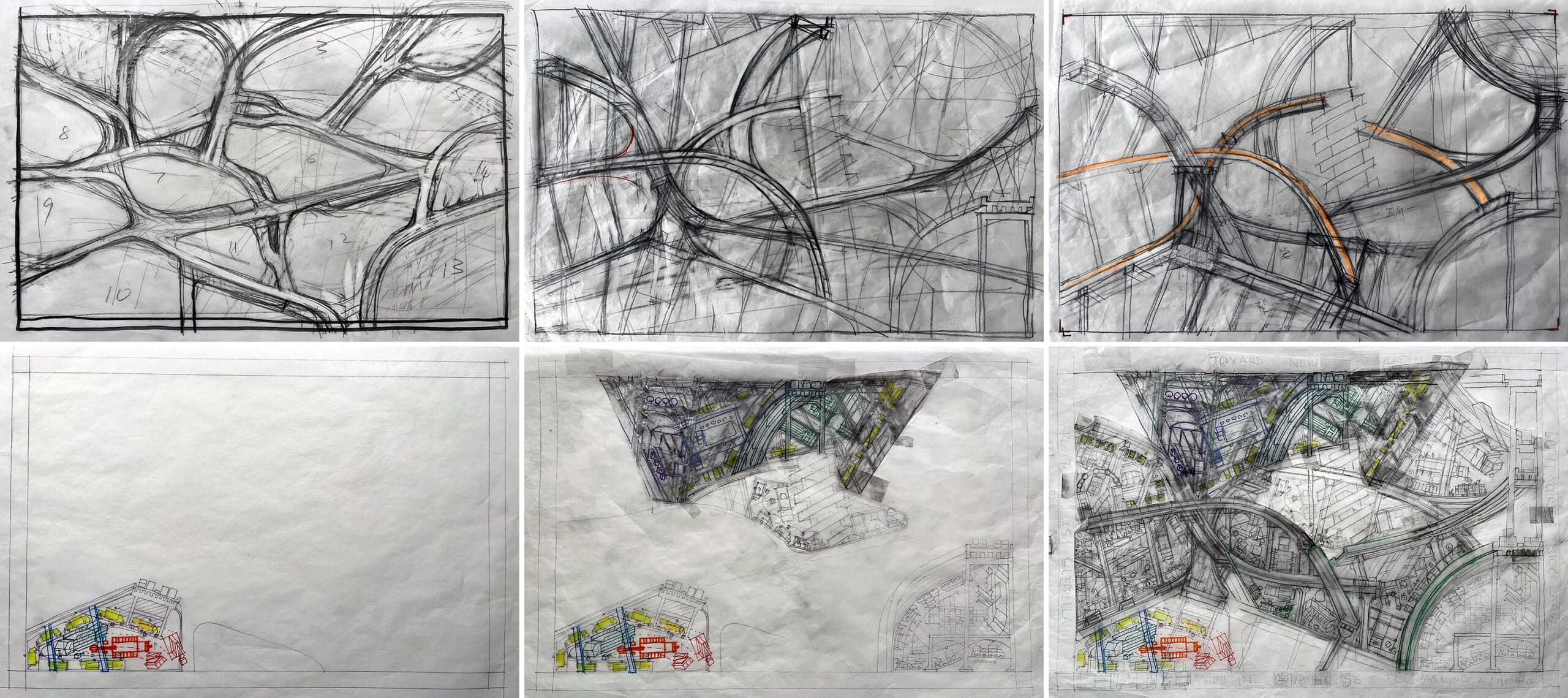

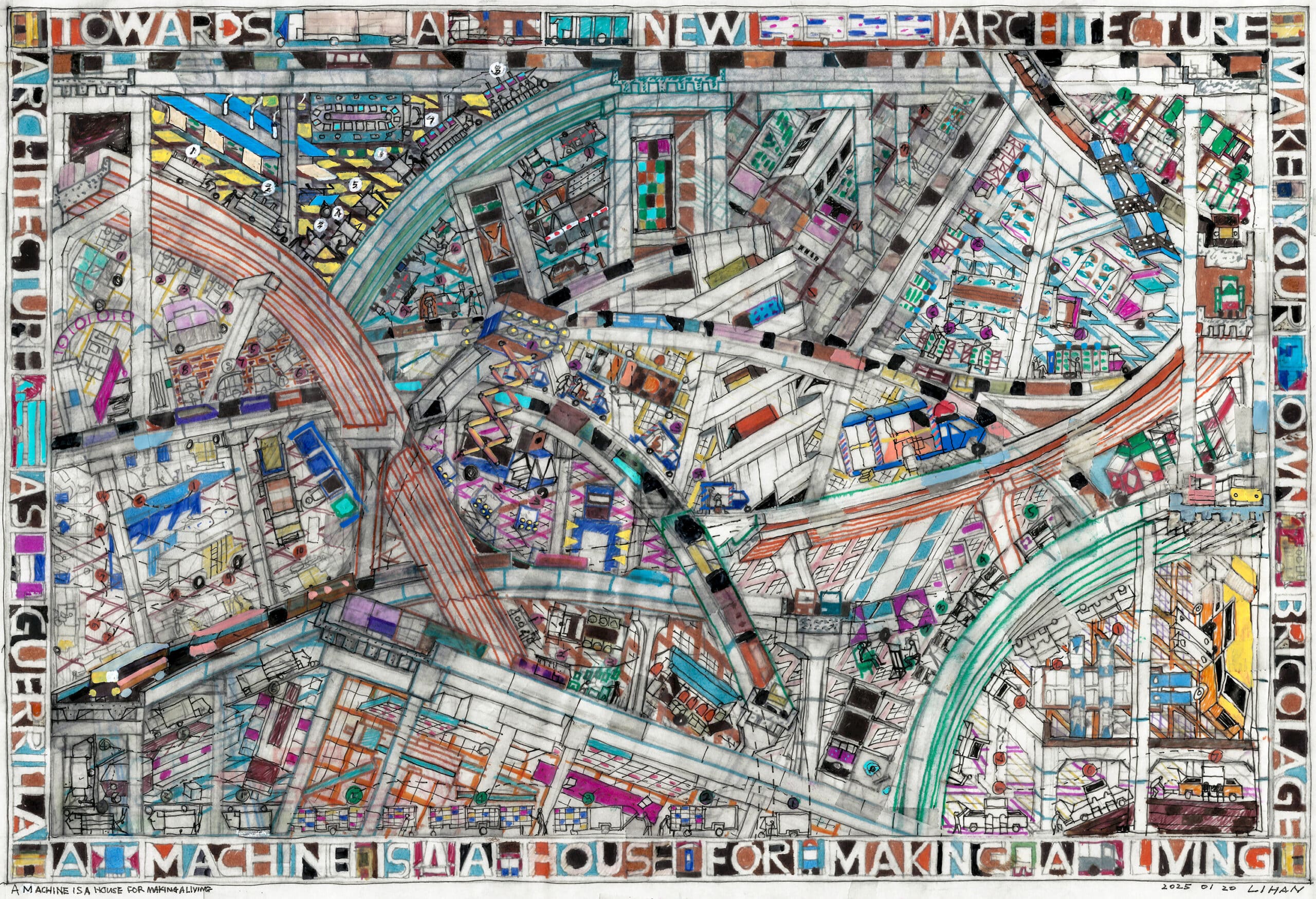

The answer lies in the process. We began in the traditional, architectural way—sketching with pencil on tracing paper. The first sketch was a rough network of roads. Gradually, we added volumes, fitting vehicles into the gaps. The final composition was built as a collage: we drew elements separately, cut and layered them, polishing our ideas as we went. For us, sketching is not about speed—it is about experimenting, and gaining clarity through refinement.

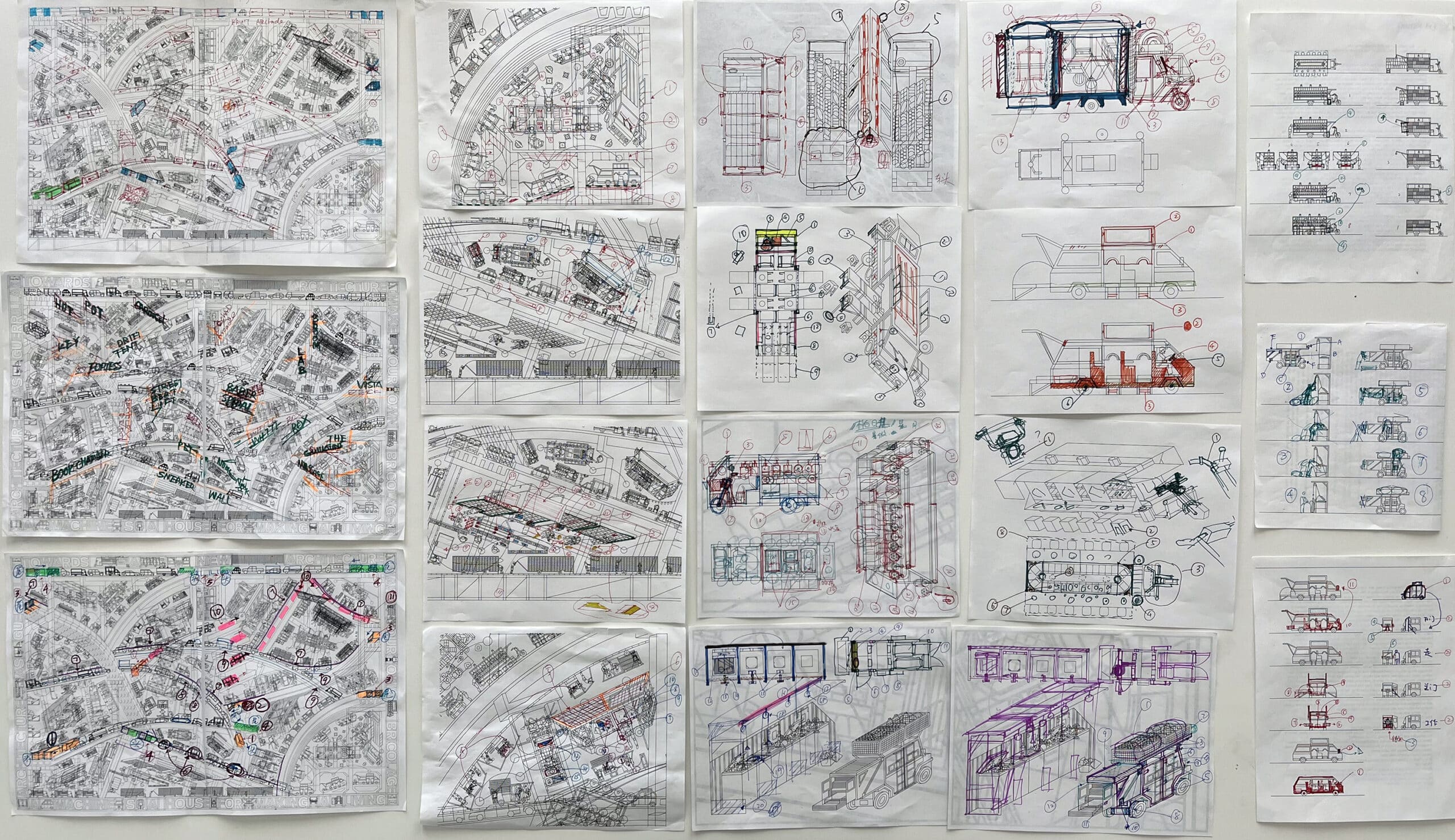

Once the sketch was finalised, we spent two more months producing a detailed digital line drawing in AutoCAD. With dozens of layers of linework, we treated the drawing like a working drawing and a construction document. For us, architectural drawing is not only visual—it is a constructive system, a way to coordinate a team and build something together. We printed the drawing at different scales, annotated it by hand, revised it on the computer, and collaborated to push it forward. A deeply personal drawing became a collective endeavour.

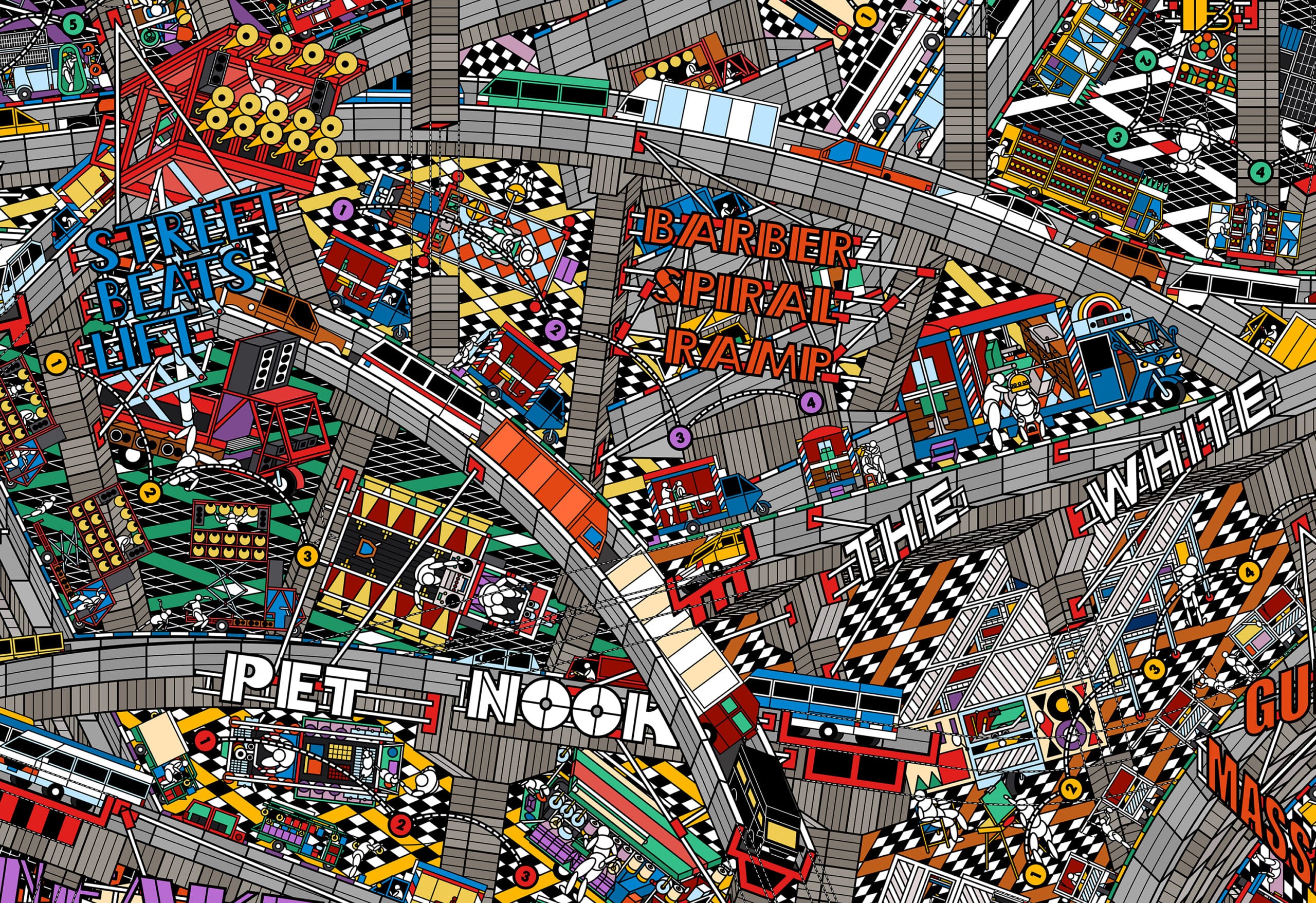

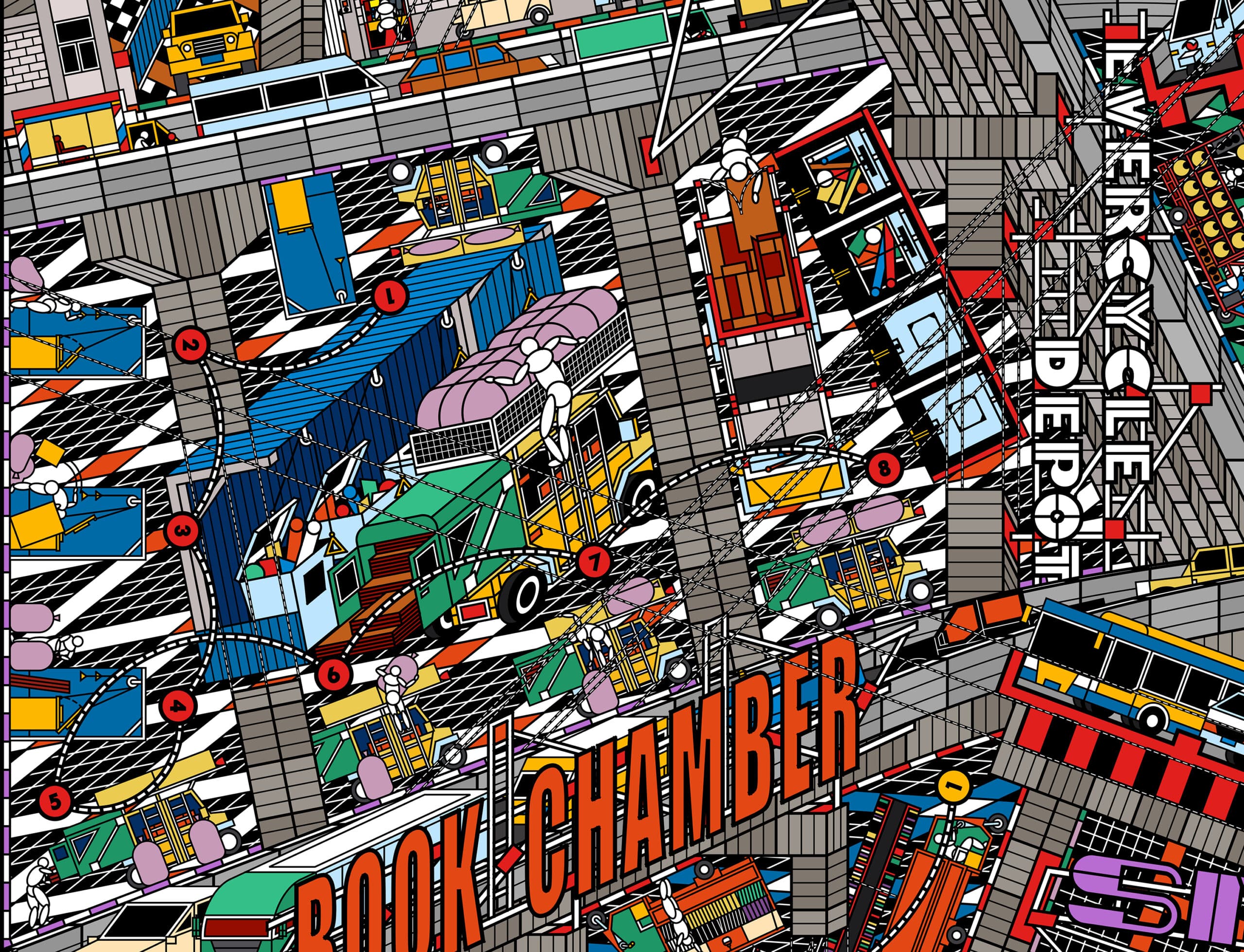

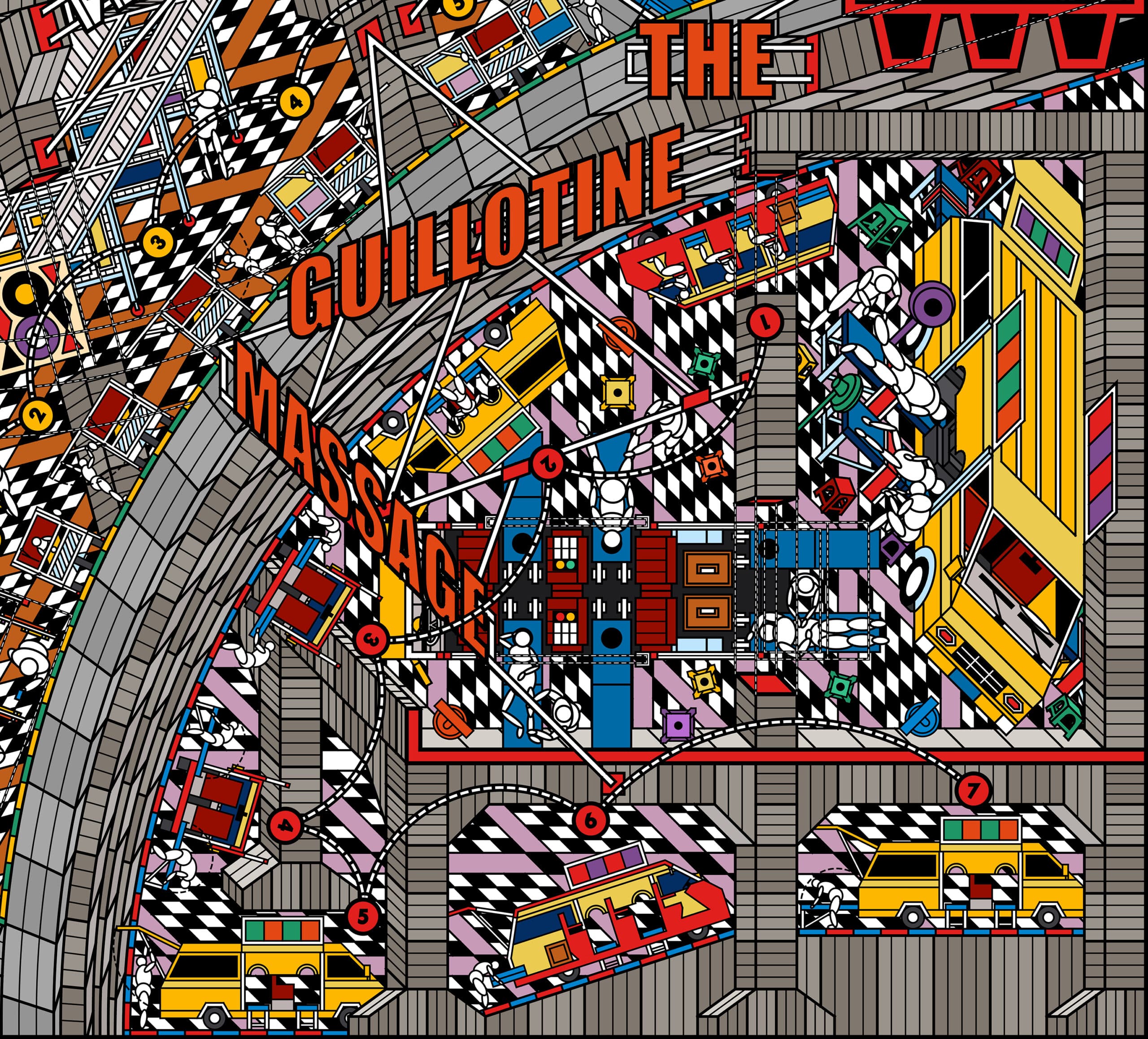

The composition of the drawing—structured around a network of giant overpasses—mirrors the actual spaces of a shop: a numbered sequence of small-scale elevations and sections reveals the steps, while a pair of large-scale plan and axonometric views renders the shop in full operation.

Viewed closely, each element in the drawing seems simple. The complexity comes from the structure as a whole and the relationships created between the different parts. We also use a ‘blending in’ approach to the figure-ground relationship—interweaving intricate lines and colours so that some areas become nearly indistinguishable—to highlight how street vendors and their ‘houses’ have become inseparable from the fabric of urban life.

To reinforce the link between machine and architecture, each of these ‘machines’-drawings is given a name referencing an architectural form—some playful, some metaphorical—and turned into a large sign rendered in bold typefaces. Installed along the overpass, these signs resemble public declarations made by their owners, echoing the written statements in the drawing frame—our responses to Le Corbusier’s claim. More than just carriers of information, the letterforms become graphic elements in their own right—like accents in a piece of music, they break the visual rhythm of the image to add emphasis and variation to the overall composition.

But the importance of the drawing is not in how well it visualises a concept. When we finally saw the full-scale piece—six metres wide and four metres tall—installed at the Pavilion Le Corbusier in Zurich, the original concept faded. What remained were its materiality: the lines, the textures, and the colours. What resonated was the time—three months of attention, argument, and correction embedded into every corner of the drawing. What emerged was a kind of craftsmanship, the accumulated traces of collective labour.

*

Drawing Architecture Studio, founded in 2013 by Li Han and Hu Yan in Beijing, is a cross-disciplinary practice that focuses on architectural drawing, spatial design, urban studies, and artistic creation, exploring the cultural expression of architecture through diverse media.