Wood & Harrison: A Film About a City

– Paul Harrison and John Wood

We are not architects. I mean, if you insist, we could probably knock something up, but we are not that good at maths, and not really that great with materials. ‘Wood and Harrison – Architects. You’ll be knocked out by our buildings’.

But we have always been interested in architecture. Not really in a pure sense, though, we love architectural drawings and models, but our real interest is when those perfect ideas meet the not-so-perfect people who will inhabit them. The building that houses our current studio underwent a major refurbishment a few years ago by a well-known architect’s practice. They redesigned the individual studios without doors to allow for ‘the free flow of ideas’, which obviously resulted in ‘the free flow of equipment’. Within a few weeks all the artists had made ‘idea flow blockers’ so they could lock up their studios. The idea had a kind of beauty and would have worked beautifully, without people.

A door is a brilliant thing. It’s a swingy bit of wall that lets you in, keeps you out, keeps you in and lets you out. It’s a basic architectural element. Doors are just one of the architectural elements we’ve played around with since we started to work together in 1993. We play around with these basic elements basically. Partly, because we like to keep things simple; partly, because we have to keep things cheap. Cheap is a relative term, of course. So is scale.

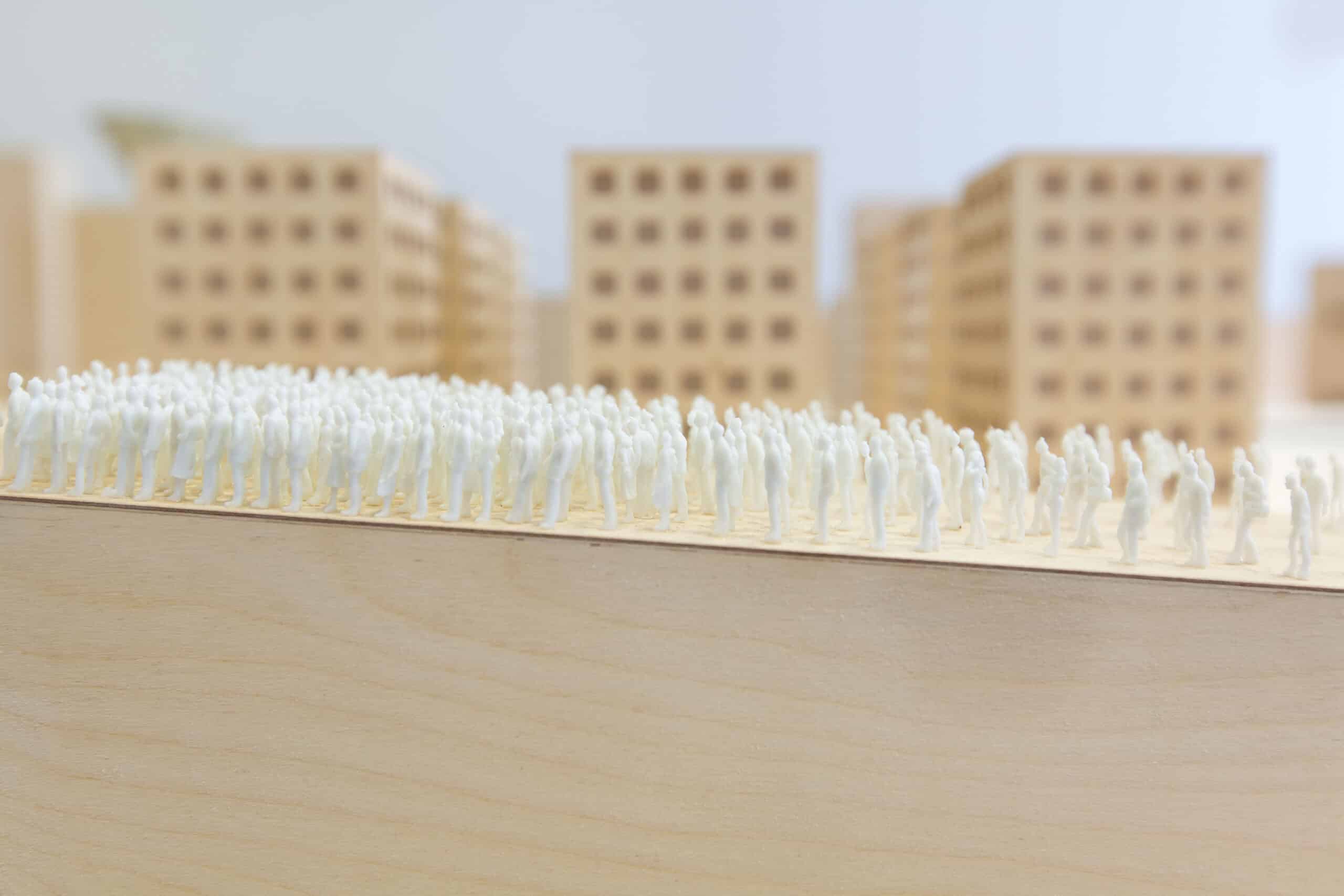

John is cheaper than me. A slightly different scale, different gauge. If everyone in the world was closer to 5ft than 6ft, then the world would look different, a bit. Things could be just that little bit smaller; the world would look just that little bit bigger. If everyone in the world was closer to 5mm than 6ft, then we could build whole cities out of next to nothing and for a fraction of the price – albeit a difficult fraction to work out, because as I’ve said we are not that good at maths and mixing metric and imperial does not help.

Being not that good at maths and not that great with materials does not seem to matter too much if you want to become an artist. It matters quite a bit if you want to become an architect, we imagine. It matters because we imagine people dying, if say, you were a bit out. We are often a bit out. And really, even if we are a lot out and we make a terrible bit of art the worst that can happen is that someone suffers a mild disappointment. And no one has died from a mild disappointment since the eighteenth century.

We are not going to not get paid if we are a bit out. Partly because artists quite often don’t get paid, even if they are in. Partly because part of our jobs can be to get things wrong, on purpose. Unlike architects, I guess we have permission to make things un-work.

A film about a city is a work about things that un-work. Things that are badly designed because of lack of thought; things that are badly designed because of bad thoughts; things that once worked but no longer do; things that should not work and, in fact, do not.

A film about a city is also a work about things that work. Things that are well designed through no lack of thought; things that are well designed and well meaning; things that have always worked; things that should not work but, in fact, do.

A film about a city is a title that un-works. It’s not even a film. Though it started out as one and the un-working title just stuck in our heads. But being in an actual city is a bit like being in a film: the way it looks, the way you look at it, the way you look in it. Its soundtrack, its framing. It’s a collection of pictures running one after the other. Every city is a film. Even Wolverhampton.

And every film starts with a storyboard. Well, maybe not starts: the storyboard is part of the way along, a part of the story. Before that, in the bit before, before the first half-thought, there is nothing. In retrospect it’s easy to see the plan, but when you are there, it’s uneasy. It’s confusing. You can do anything (or nothing, that can be a work too). Somewhere in this confusion, this unease, somewhere in that bit before, the film about a city stopped being a film.

So, our storyboard became a series of badly laid plans, and the bits of something, slowly, became a thing. An architectural model of a city. But it isn’t like most architectural models, it was a lot cheaper for one thing, and for another thing, it was the thing. There was never going to be a real city, an actual one. For 6ft, 5ft or even 5 mm people.

Maybe this is the fate of lots of architectural models. To endlessly travel the world, which they hoped to shape, in the shape of an exhibit, in a show of architectural models. There’s definitely a market, there is always someone somewhere showing them. And people love them, I mean really love them. And they love them, in part, because it reminds them of being a kid, and they miss that.

This pre-existing fascination was something we, of course, realised we could tap into. And whilst the viewer was imagining being a kid imagining being really small and imagining running around in all the buildings, hopefully they would be looking and hopefully noticing…

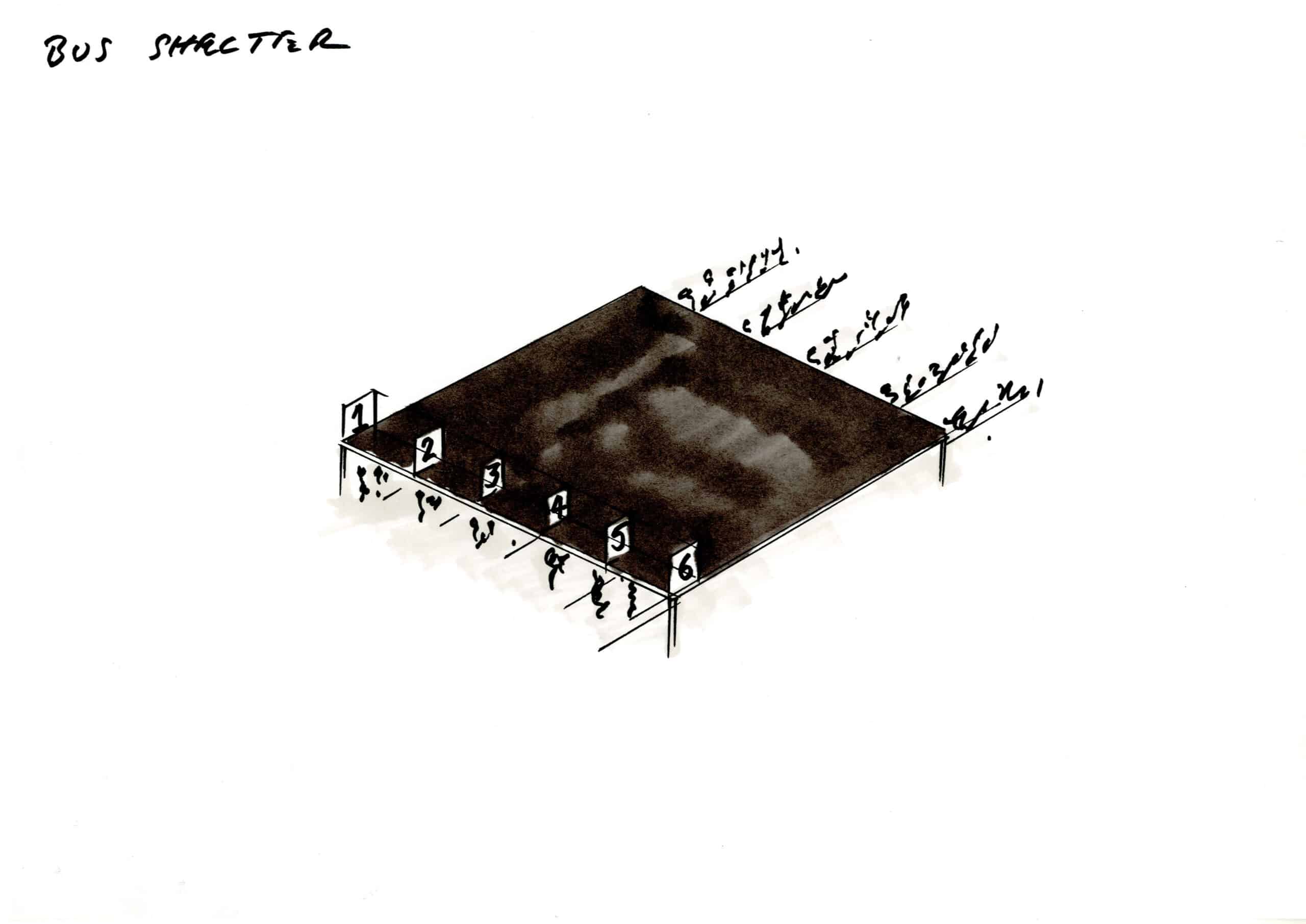

…the bus stop designed meanly for mean customer numbers…

…the penthouse only tower (why build the rest? Just build the most profitable bit)…

…the circular building, designed with the aid of a pair of compasses, obviously, because they’re still there, stuck in the roof…

…the fourteen men who meet on seven benches, or is it the same two men who meet on the same bench every day of the week?…

…the two parts of the same factory, linked by an annoyingly inconvenient bridge…

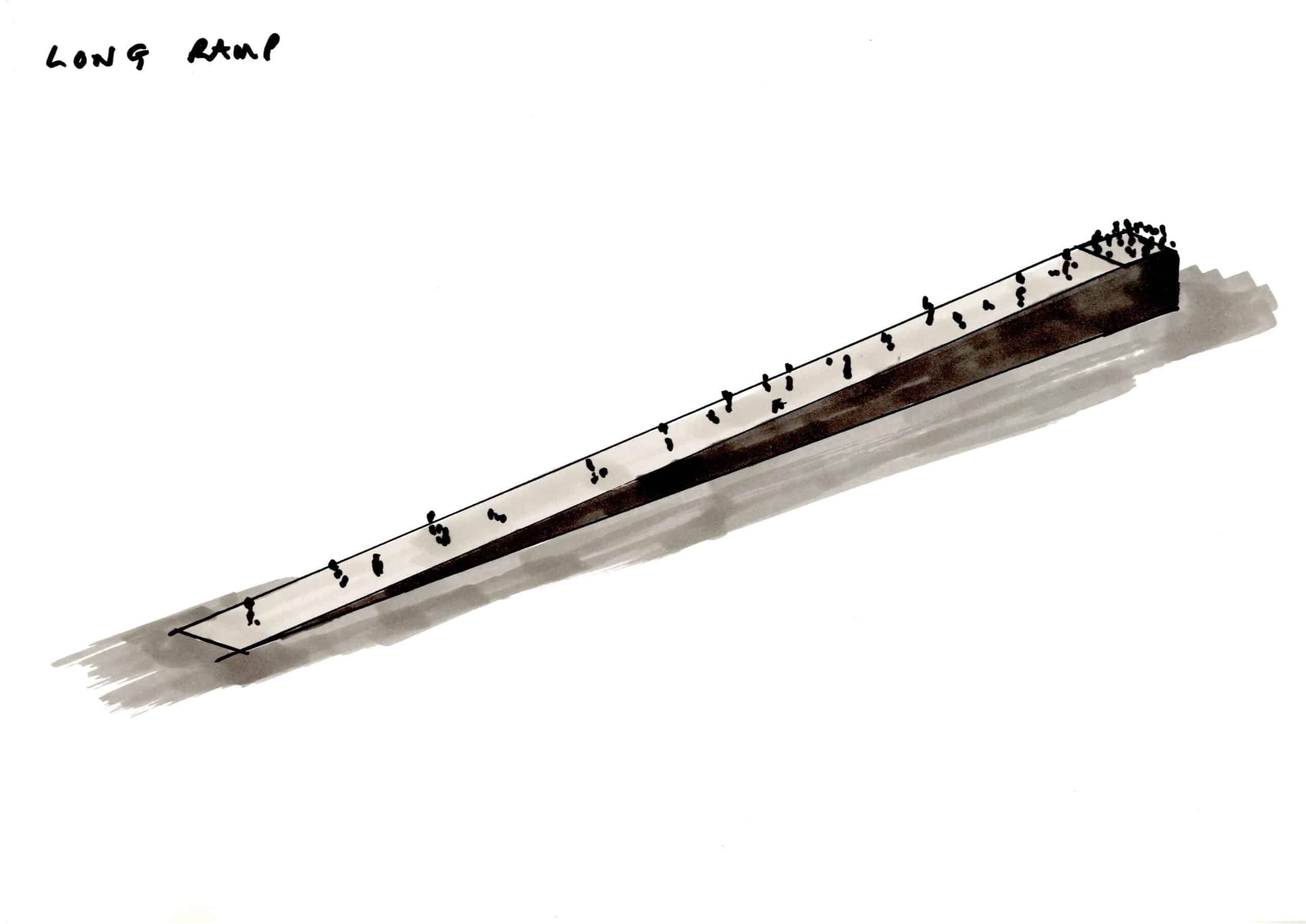

…or the long ramp, that you walk up, pause, then you walk down again, for some reason…

And all the other bits and pieces, and the bits and pieces in between the bits and pieces that make up the work, that make up a city.

We’re not really into master plans. We like the beautiful mistakes, the beautiful takes, the improvised uses, and misuses, the comedic moments. The bits and pieces in between.

But then again, we are not architects. It’s probably for the best.