A Poetic Peak: Architecture and planning at the AA in the 1930s

– Editors and John Summerson

In 2022, Drawing Matter acquired nearly 100 drawings by the architect and urban planner Elizabeth Chesterton. Mostly for projects done while studying at the Architectural Association (1933–38), the group includes drawing exercises, such as colour theory, sciography and graphic design, and a wide variety of buildings at different scales, from a telephone kiosk to the short-lived building typology of the ‘milk bar’ and urban planning. While most of the drawings carry title blocks and some description, within the group there are several drawings, site plans, sections and perspectives, that initially offered few clues about the projects for which they were made.

The period in which Chesterton studied at the Architectural Association was particularly turbulent and saw several conflicts between the school’s council and student body.[1] It was also a period of pedagogical experimentation and innovation. One of these innovations was the establishment of the School of Planning and Research for National Development (SPRND), set up in 1935 by E. A. A. Rowse, at that point assistant director to Howard Robertson; the SPRND was the first programme for postgraduates that approached planning as a subject in its own right, rather than an extension of architectural studies. The following year, Rowse was appointed as principal of the school and introduced the ‘unit system’ of 15 term-based units each led by a master, replacing the structure of five large year groups.

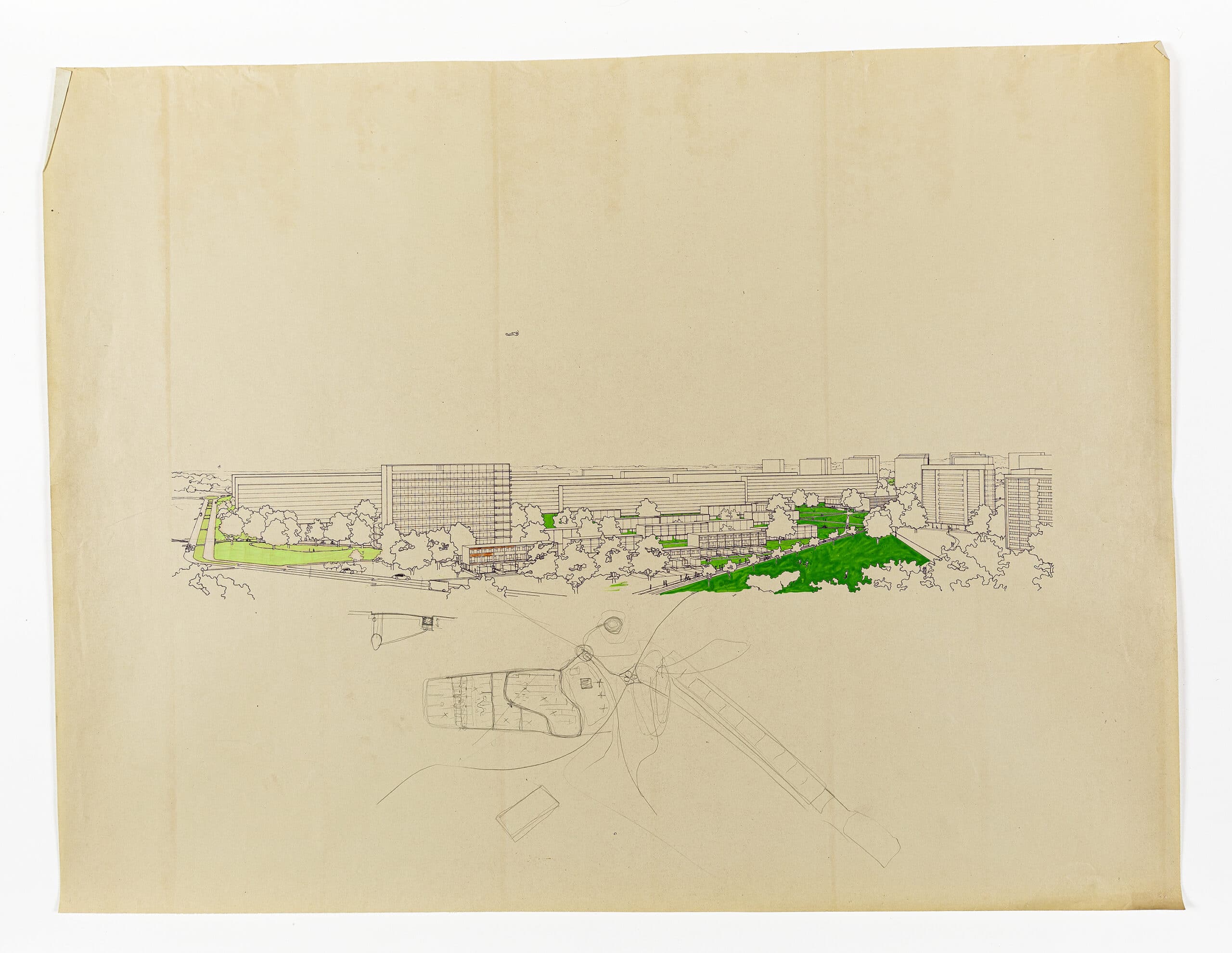

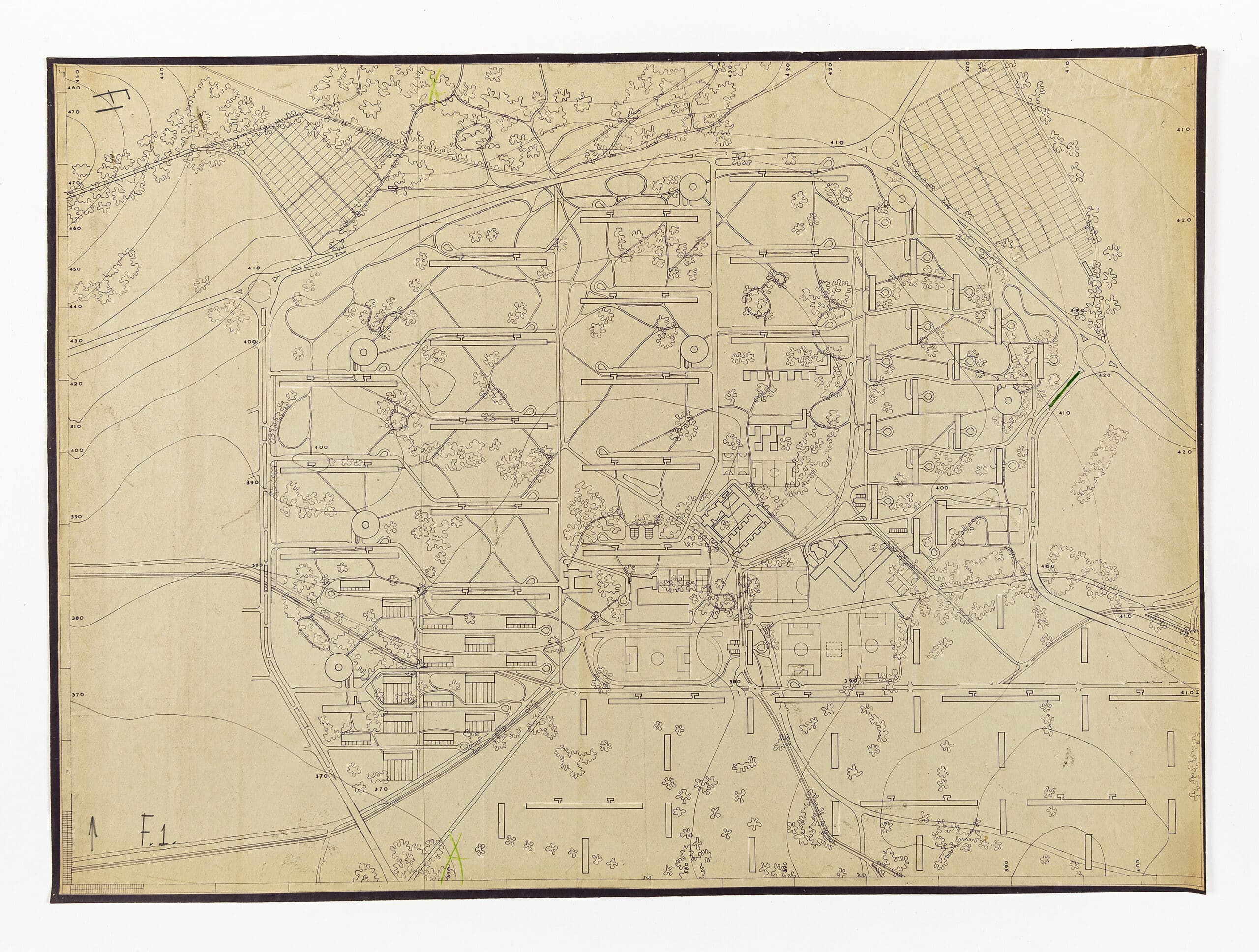

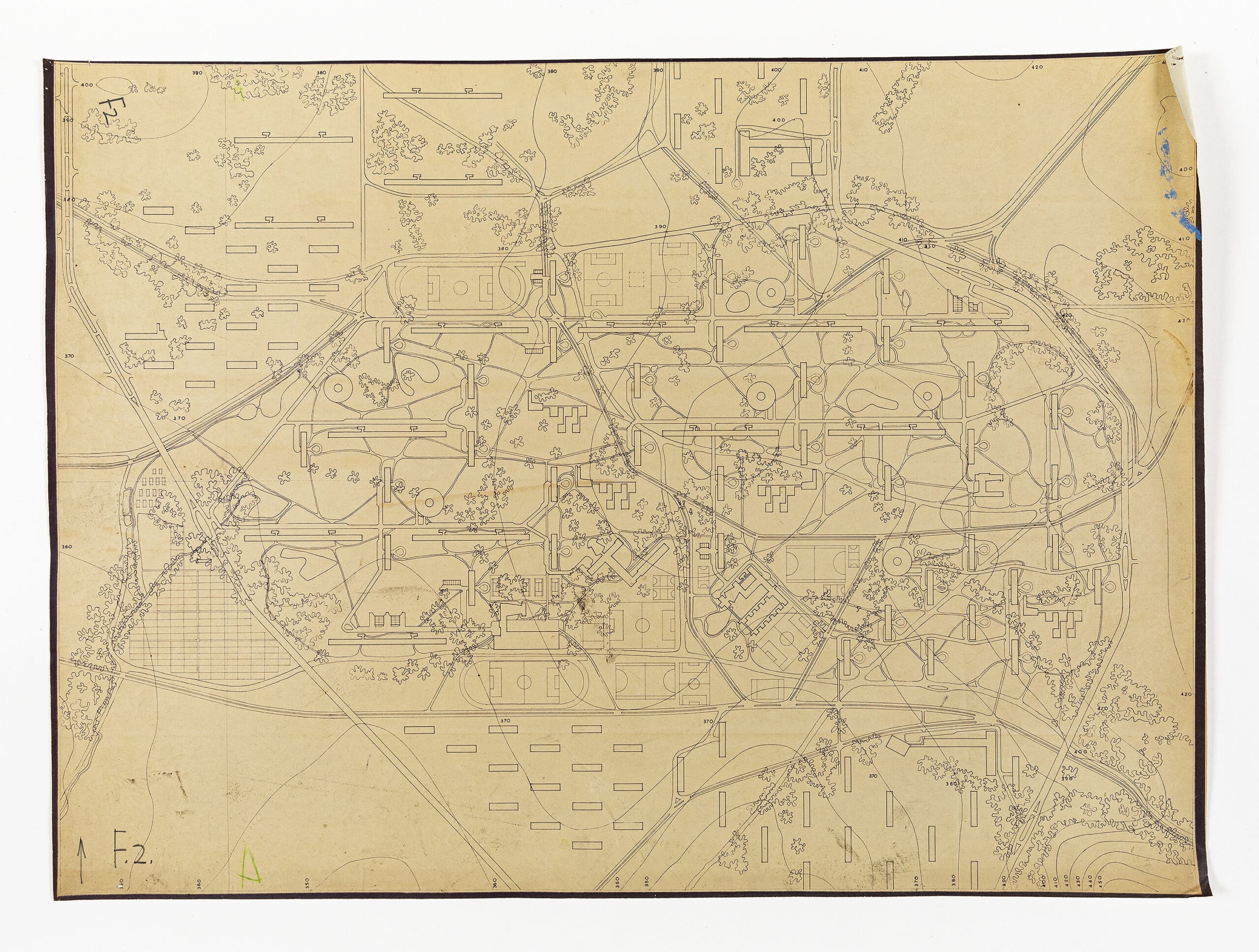

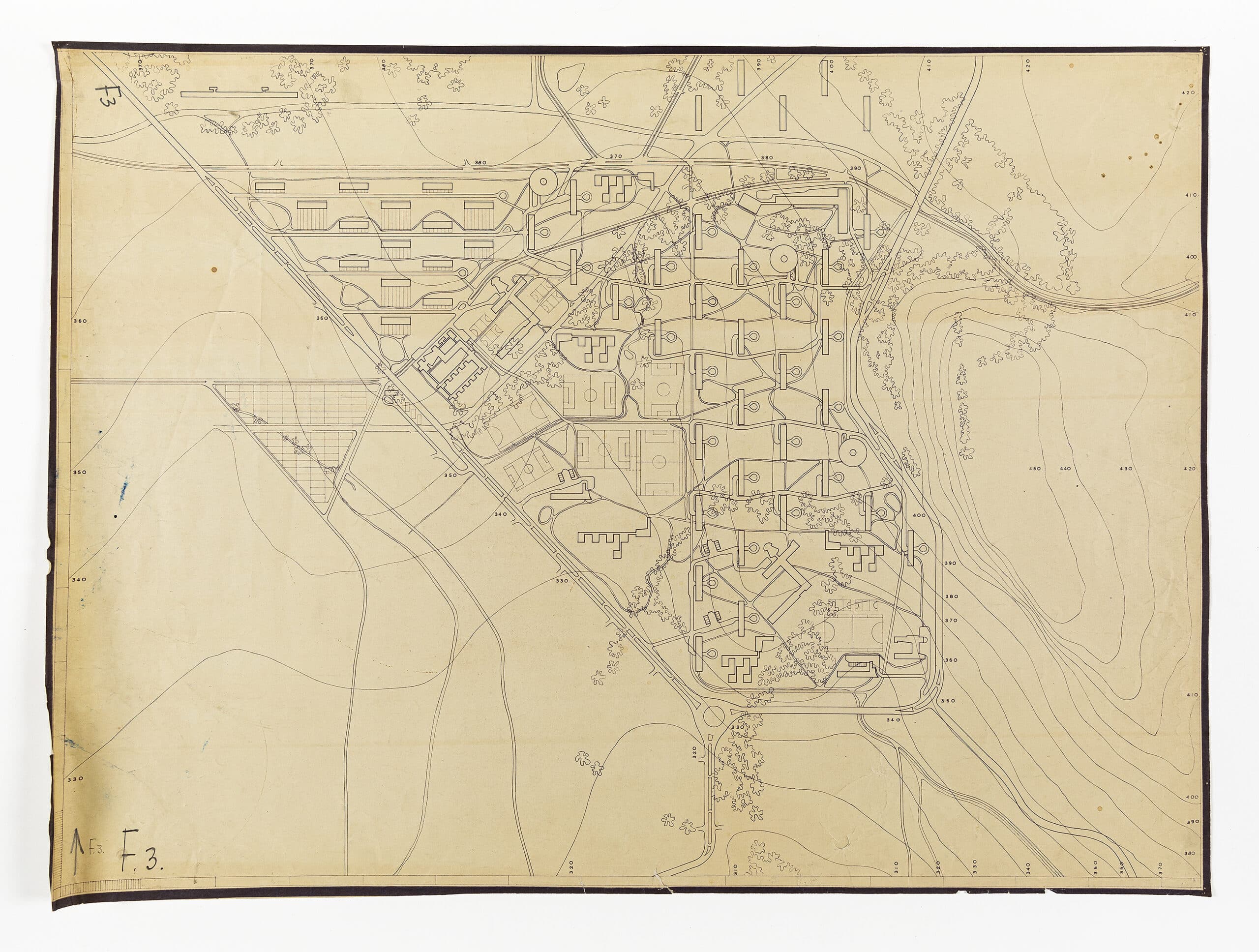

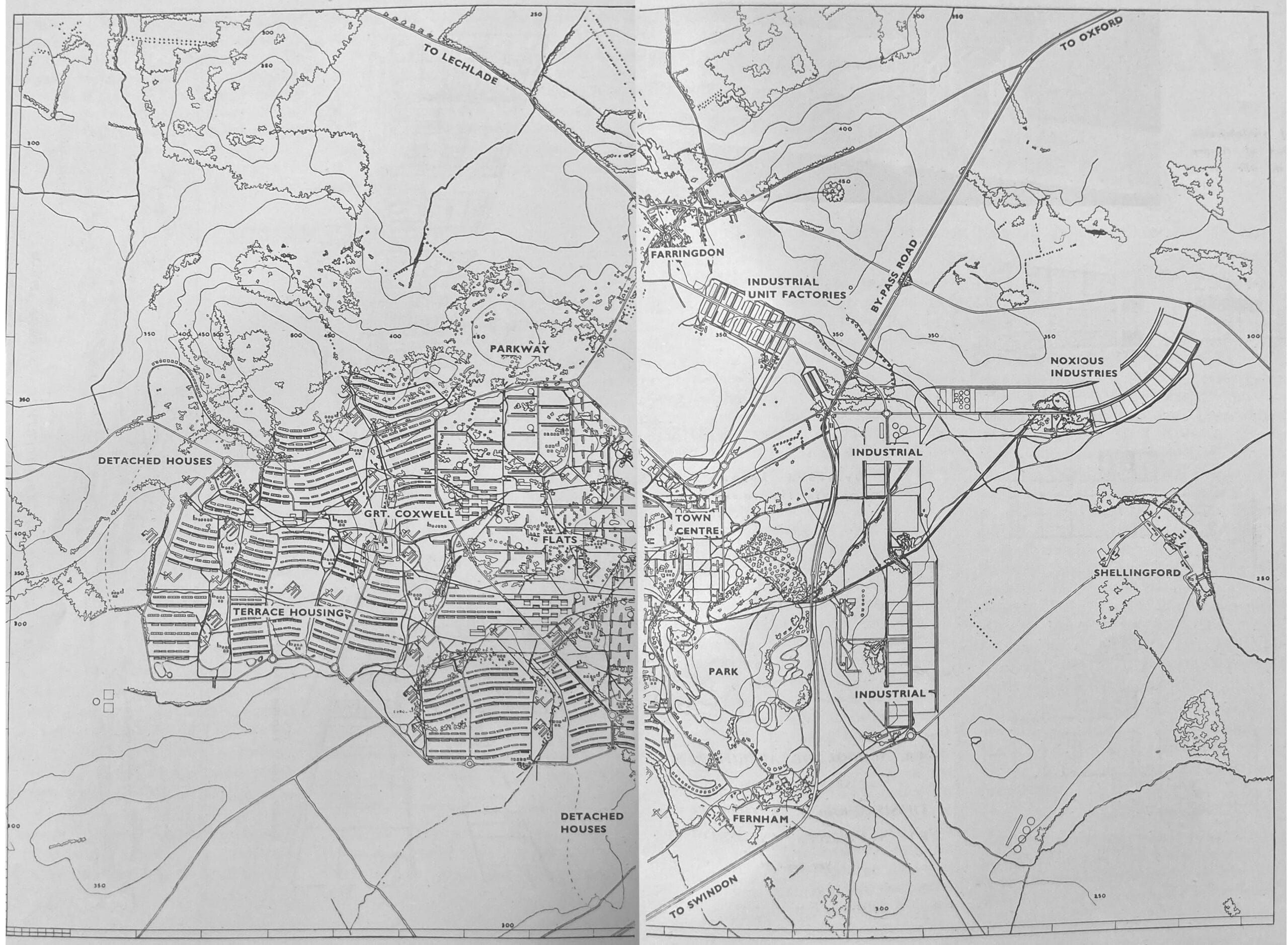

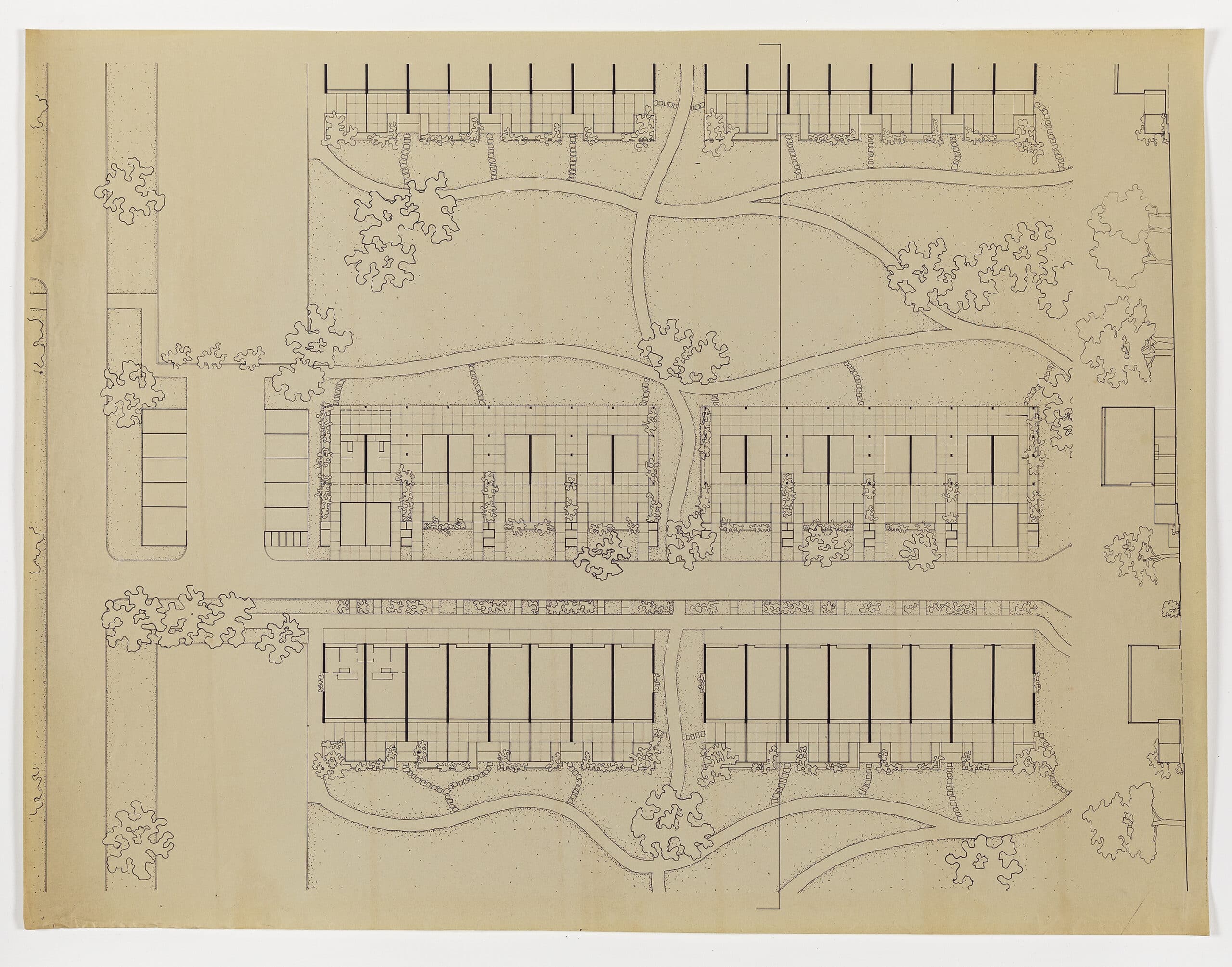

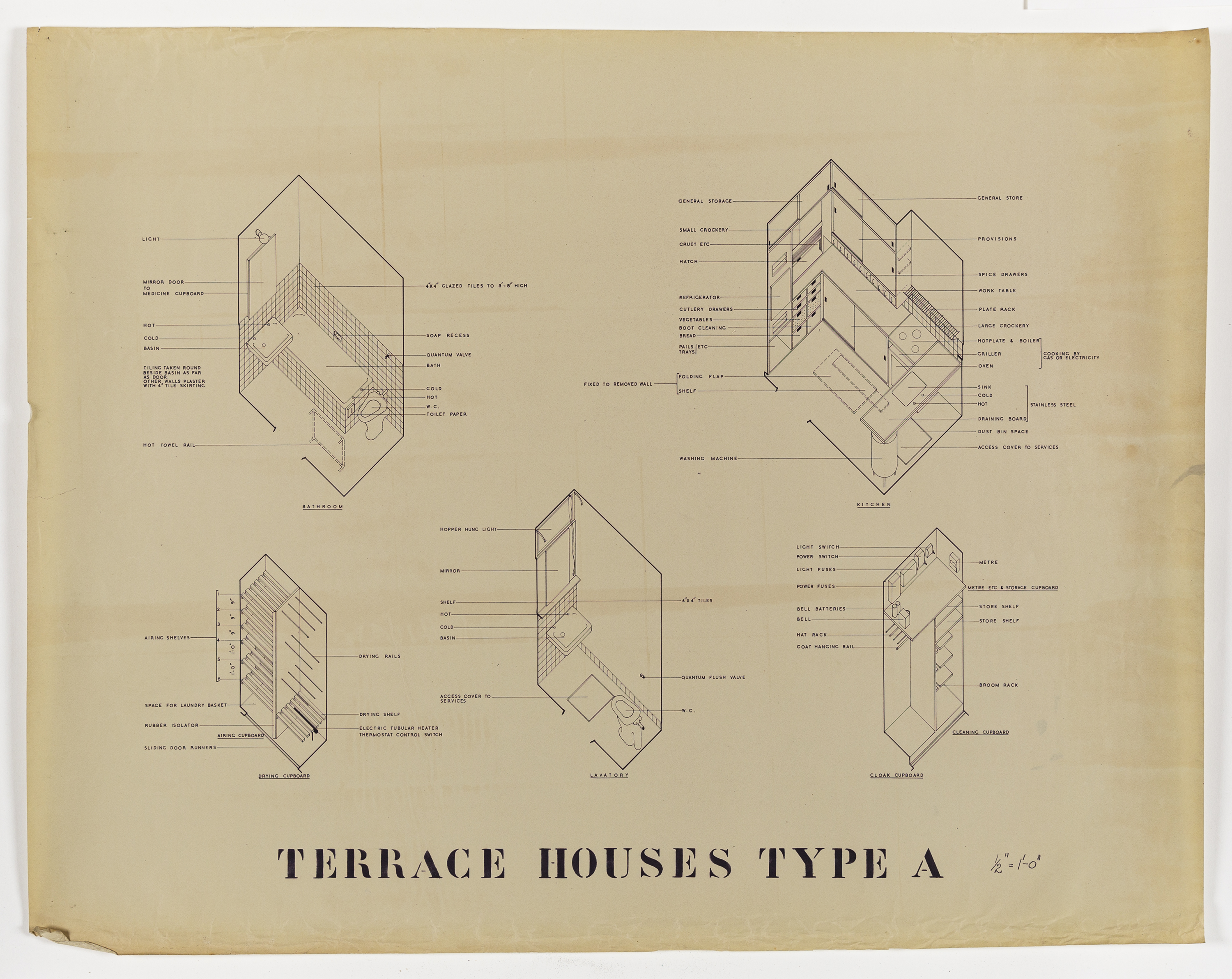

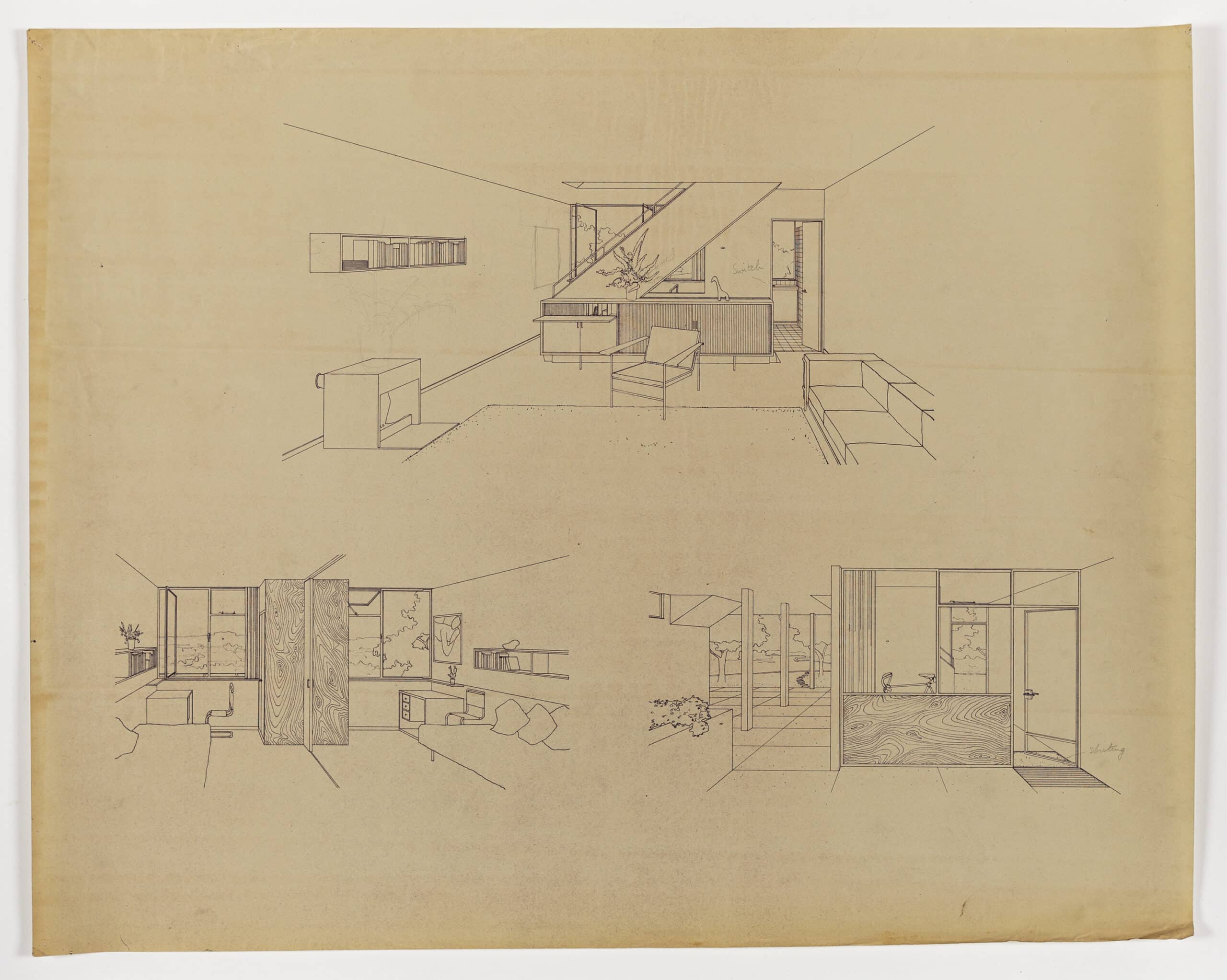

A key aspect of Rowse’s new structure was an emphasis on group collaborative projects and it is for the most famous of these exercises that the untitled Chesterton drawings at Drawing Matter were made. In 1937–38, the 15 students of Unit 15 produced a collaborative thesis project of a Town Plan—known also as ‘Tomorrow Town’—for a site near Farringdon in Berkshire. The project was published in the September 1938 issue of the Architectural Association Journal, with an illustrated commentary that praised the initiative, describing it as a project that demonstrated ‘the great advantage of properly organised co-operative work, both in providing first-class training for the more advanced student, and as a means of making a significant contribution to contemporary thought’.[2] It was subsequently published in the inaugural issue of Focus magazine (Summer 1938) and included in the RIBA’s Road Architecture Exhibition in 1939.

Despite the positive reception of Unit 15’s work, Rowse’s tenure as principal only lasted until May 1938 when he was removed from the position after friction with the school’s director, Harry Goodhart-Rendel, who objected to Rowse’s experimental teaching methods. However, in an indication of the fraught situation at the school, Goodhart-Rendel himself did not last much longer, resigning four months later.

One of the enthusiastic reviewers of the 1938 exhibition of student work and the Unit 15 project was John Summerson:

I am not sure whether anyone not in practice can usefully comment on the work of those whose chief aim is to become fit to practice. If I thought it would help, I would quote the tag about the onlooker seeing most of the game; but in the interests of candour I will merely hint at the probable futility of my writing this article at all and ask you to accept my remarks for what, if anything, they are worth.

What impressed me chiefly in the exhibition was the consistency of outlook which it obviously reflects. From top to bottom of the school, everybody seems to agree upon what kind of architecture is worth making. Consistency of this kind could not possibly be imposed. It must come from the students themselves. I have seen a fair number of school exhibitions, at the AA and elsewhere, but never one with this singular unanimity stamped all over it. It is very extraordinary indeed.

Where does this unanimity come from? What does it mean? Is it as good thing? The last of these questions is controversial but some consideration of the first two may be pertinent. To begin with, the outlook which the exhibition represents is that of a minority movement in the profession. On the face of it, it is strange that students should be irresistibly drawn to such a movement for it is one which does not by any means follow the peaks of material or academic success in the outside world. A few eccentric devotees would inevitably be claimed by any new stylistic departure, but this wholesale loyalty is a different thing altogether.

To my mind there is only one answer, and that is poetic appeal; and the poet is the Ruskin of our age—Le Corbusier. Like Ruskin, Le Corbusier has placed architectural activity in a new context. Ruskin, a literary gentleman, conceded that as the conditions for the kind of architecture he believed in did not exist, decent architecture was impracticable. Le Corbusier, on the other hand, flashed into the architectural firmament a few brilliant novelties, closely related in spirit to the Paris school of painting, and then proceeds to show that they are the very embodiment of present-day conditions with the integrity and detachment of a poet.

Now, there you have a kind of appeal which is utterly irresistible—at least to those whose minds are young and susceptible. It is, mark you, not merely a question of the influence, through his designs, of a very brilliant architect on his younger contemporaries. That is a phenomenon familiar to everybody who has the knack of detecting fifth-hand clichés. Le Corbusier is something more than an architect and the only word I can think of to describe him is poet.

Obviously, this poetic conquest has got to be accepted. There is no arguing, no going back. But now comes the real test of the work by the AA Students. Is this capitulation to new rhythms, new silhouettes, new plan-shapes, merely a tribute to someone else’s discoveries or does it represent that spirit of adventure and realism which is its original justification. I confess that when I see kidney-shaped garden beds, arbitrary chunks of rubble, windowless walls made of pre-cast slabs in alternate wide and narrow bands, and draughtsmanship á la Ville Radieuse, my worst suspicions are aroused. Dangers lurk everywhere in this sort of thing. How beautifully the ruling pen defines those tense, exquisite pans de verre!—but what is really happening where the glass approaches its concrete surround and what would it really look like if it were constructed? As I said, I am not a practising architect, and I imagine that unless one has tried to build this sort of thing, oneself it is impossible to judge of the practicability of succeeding. What I do know is that the vilest buildings I have ever seen are the modern adventures which, either from lack of funds or lack of competence, have flopped.

I do not think these obvious dangers invalidate the point of view. And it is the point of view itself that matters—the method rather than the results. Results are a mere question of style. Falling in love with a style is a thing that happens to every young architect. To marry a style spells disaster.

What I think everybody must agree about is that all this lovely French (or should I say Swiss?) poetry, so fully appreciated and so beautifully re-created in the Thesis and pre-Thesis designs, is all right so long as there is behind it that spirit of curiosity and unflagging enquiry whose encouragement is the first and last duty of architectural education. So long as that spirit is there—and I believe there is ample evidence of it—I don’t think that anybody need worry about the condition of architectural education at the AA.

That the spirit of enquiry is there all right is surely proved by the impressive and extraordinarily beautiful town which Unit 15 has designed on the basis of existing conditions in a portion of the Vale of White Horse. This close study of a piece of actual territory and the creation of a complete town to fit conditions which might very well exist there is as good a mental exercise as anyone could possibly contrive. The very breadth of the undertaking is bound to give confidence and power of insight to those who go through with it. I suppose the obvious criticism of this sort of thing is that it is ‘all very much up in the air.’ Perhaps it is. I noticed, for instance, in the report on structure that some of the pre-fabrication proposals were necessarily indecisive because they could not be otherwise without a try-out in a model factory. Which means that the authors are looking farther ahead than the conditions around them—trying to run, if you like, before they have proved their ability to walk. I do not think that matters, so long as they realise that is what they are doing. And what proves that they do realise it is the thoroughly practical way in which the small-house job (Unit 14) was tackled.

Looking farther back in the curriculum I was struck by nothing so much as by the evenness of development right from the first unit to the last. There used to be a kind of bottle-neck in architectural courses, around the end of the second year, when the student flopped out of his chrysalis and began floundering about with ‘real designing’. The chrysalis has been abolished, along with the bogus history represented by ‘the study of orders,’ that often fatal blow to a student’s budding sense of reality. And in that I see nothing to regret. Realism, too, is the key-note of the first year teaching and here the imaginative ‘kindergarten’ methods provide a magnificent antidote to the horrid sophistication of ‘upper sixth.’ A sense of curiosity, the urge to find out the facts is stimulated from the moment the student sets foot in the school.

I hate being optimistic, but I cannot help feeling that a school as bursting with initiative as this, is a bright spot in contemporary architecture. I sympathise to some extent with those who take fright at the intense rallying to the Le Corbusier standard. One day it will lead to disillusion. Already, in countries less phlegmatically minded than ours, enthusiasm has ebbed and the whole thing has become an unfashionable joke. That can happen at the AA. It probably will. What then? One of two things. Either a terrific ideological swing-round to old standards, as in Russia and (with a kick from the politicians) Germany. Or a general ‘settling down,’ as in Italy, to local modern idioms which fit in very amiably with local conditions. The latter alternative is the good one, for it still leaves the door wide open to the explorer and gives time for the architects, the public and the building industries to come to terms in the light of what has been happening.

We must face this fact. Architecture does not rush from one poetic peak to another. There are the long, level plains and they need not be in the least squalid. Now the work of a school is bound to epitomise both peaks and plains and it is probably true to say that in ‘peak periods’ students will rush ahead and try to out-top the highest, while in ‘plain’ periods they will come to heel and follow the general standards of practice. In ‘peak’ periods, like today, architectural education becomes a most ticklish job, but I think the AA is riding (if you will forgive one last change of metaphor) the storm.[3]

Notes

- For a history of the AA in this period see Patrick Zamarian, The Architectural Association in the Postwar Years (London: Lund Humphries, 2020).

- R. Cotterell Butler, ‘AA. School Cooperative Thesis Unit 15: Design for a Town,’ Architectural Association Journal, September 1938, 89–90.

- Reproduced from John Summerson, ‘AA School of Architecture: Exhibition of Students’ Work, Session 1937–38,’ Architectural Association Journal, August 1938, 67–69.