Geoffrey Goes to Basildon

Charley in New Town is the peerless Halas and Batchelor film made for the government’s Central Office of Information in 1948, offering a utopian vision of new town living to the dazed postwar urban public. There is something of Charley, pedalling around the streets of the immaculately clean, smoke-free, Neo-Garden City, head high, that evokes Geoffrey Jellicoe. While Freddie Gibberd, moustachioed and with self-confessed melodramatic tendencies (which he revealed on Desert Island Discs many years later) did nothing quietly, Jellicoe did a huge amount of essential housing work, both during the war and after, pressing on to the next commission, the next site, without undue noise. He designed seven schemes for the Ministry of Supply in 1941–42, which urgently needed accommodation for war workers, largely in the West Country. He alleviated their strictly functional nature (which, as Finn Jensen points out, included a room specified as an air raid shelter) by his sensitivity towards the topography of each site and its existing landscape. As master planner at Hemel Hempstead in 1947 he married that experience with an increasingly inventive landscape approach, in particular later on with the central (newly restored) Water Gardens. He was beginning to enjoy himself after the rigours of running the Architectural Association during the war and the years of highly circumscribed architectural practice.

Working in partnership with Francis Coleridge and Allan Ballantyne, the latter based in Plymouth, Jellicoe’s office was busy in the mid-1950s including housing for Basildon New Town. Guided by the objectives of the Abercrombie Plan (1944) to deal with the ‘sprawling growths’ around Billericay, Laindon, Pitsea and Wickford and to ‘concentrate and to a certain extent urbanise the central areas of these towns’ the Basildon Development Corporation had begun to systematically erase what Abercrombie’s report saw as the disorder of the plotlands developments (their ‘ownership… shrouded in mystery’). The first wave of neighbourhood house building at Basildon involved experienced architects and planners who were nevertheless required to abide within disappointingly restrictive and parsimonious limits.

Perhaps to keep cheerful in the face of all this, Jellicoe embarked on a scheme of his own encouraged by Pilkington Brothers, the St Helens-based glass manufacturers, to think far beyond the boundaries of the rational, the possible, the tried and the tested. From 1937, the company had strenuously attempted to engage members of the architectural and engineering professions with the limitless potential of glass. After the war, the Glass Age Development Committee was formed, consisting of Geoffrey Jellicoe, Ove Arup and Edward Mills. They were licensed to dream and as Steve Parnell shows, the results usually appeared as multi-page advertisements (or advertorials?) in the Architectural Review. [1] Schemes ranged from the razing and rebuilding of Soho as a series of 24-storey glazed towers to an airport structure, Skyport One (1957), and an inhabited bridge, the Crystal Span (1963). However nothing touched the ambitions, playfulness and forward thinking of Motopia, an entire city, which appeared in two issues of the magazine in late 1959, illustrated by Gordon Cullen’s highly effective visualisations, and then as a more discursive book, under Jellicoe’s own name, in 1961.

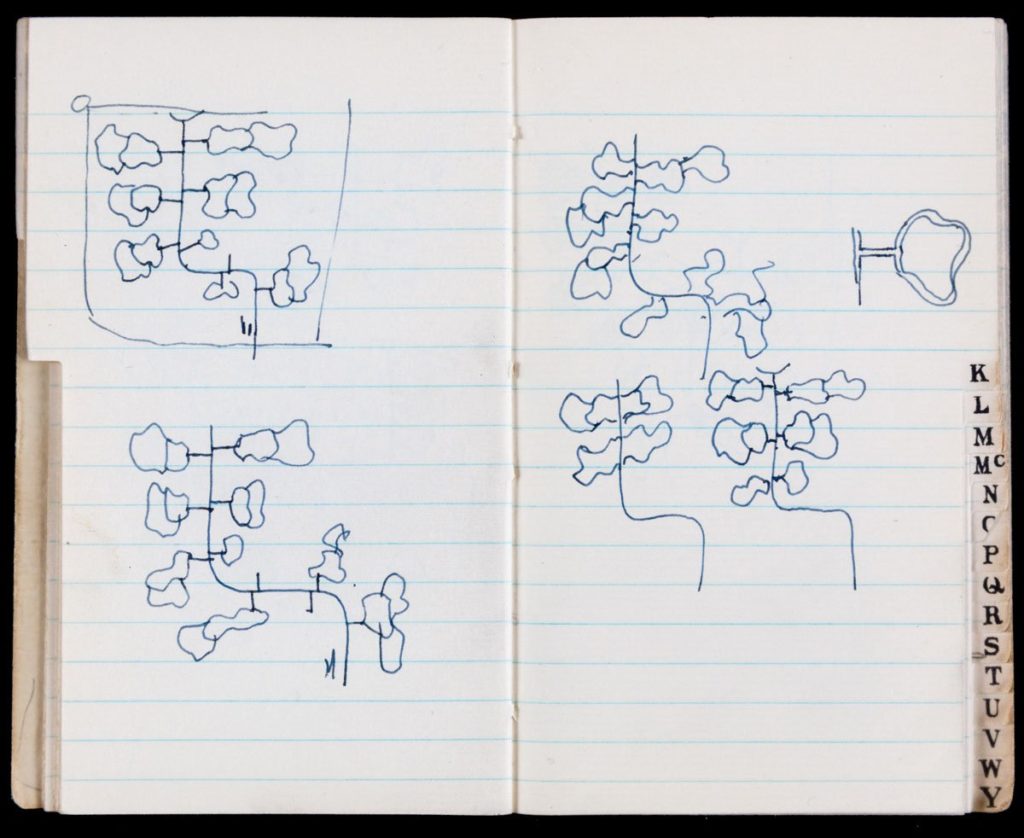

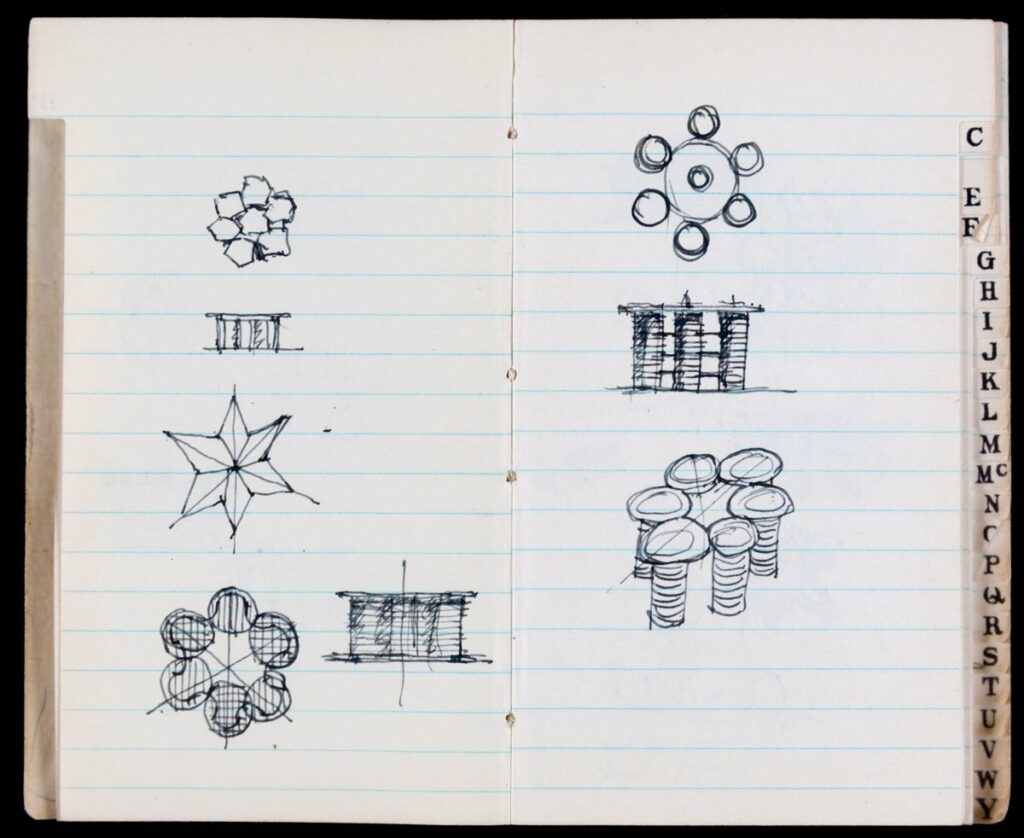

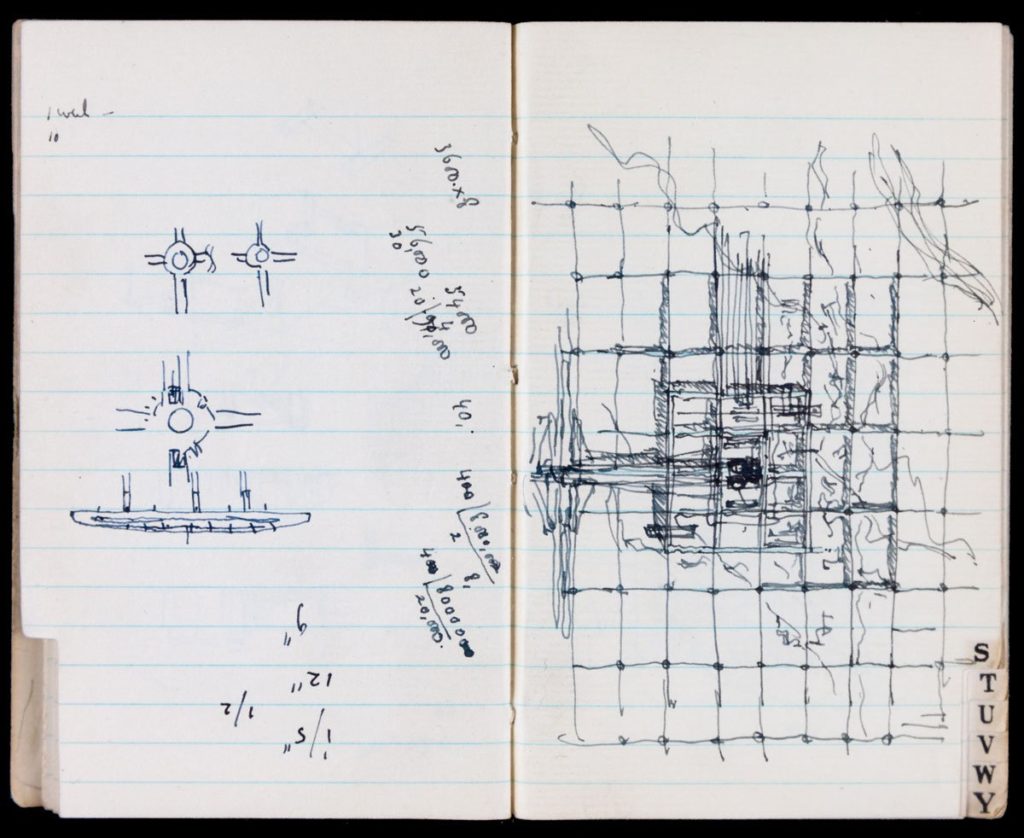

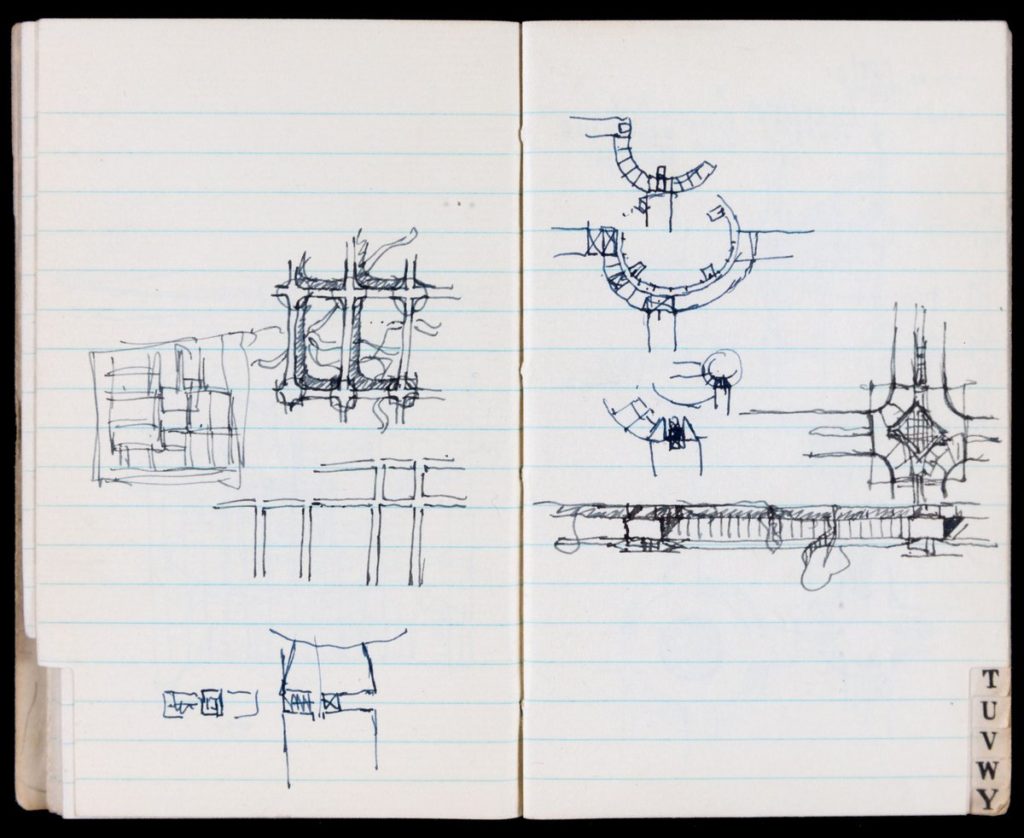

A little sketchbook, now in the Drawing Matter collection, shows Jellicoe toying with these ideas back in 1956–57 and for a moment eliding them with a new approach for Basildon, where Sylvia Crowe (the distinguished landscape consultant who was also working, much more happily, at Harlow) had admitted being depressed by the site, the soil and the client. In a note written to Todd Longstaffe-Gowan (to whom Jellicoe gave the notebook in 1984) he was asked ‘to see if it were possible for “Motopia” to be built at Basildon new town. It wasn’t but it suggests fun in the landscape.’ The sequence and application of many of the sketches is not clear, but here and there the essential grid and the circular points of Motopia emerge, along with pavilions and playful forms that might have suggested insertions in the ambitious city centre.

In the book his introduction made clear that this city plan was a design for ‘a new setting unencumbered by what already exists.’ The utopian objective was ‘an ideal environment that would give us the best of all worlds,’ an ideal town ‘in which the traffic circulation were piped like drainage and water; out of sight and mind, to go as fast as it likes, to smell as it wants, and to make noises.’ Jellicoe separates ‘mechanical and biological man,’ the car being transposed high above, onto the terraced housing at roof level, and leaving the intervening landscape for the designers of the town ‘to do with it what we will.’

There are discernible links between Basildon and Motopia (and, inevitably, between Motopia and Le Corbusier). In the book Jellicoe wrote that a single tower block, here housing offices rather than flats as in Harlow and Basildon, would house the traffic administrator, the key figure in it all, a kind of Benthamite (or Foucaultite) controller whose role in this Home Counties Panopticon is just to adjust the pinch points, the volume and congestion involved, almost like a flight controller. In such a highly coordinated universe the cyclist is considered ‘an anachronism… no cycles are allowed in Motopia’. Waterbuses and electric trains, moving walkways and paternosters will be the essential links in the chain between the regions devoted to the car and to the pedestrian.

Jellicoe can be seen in a 1959 Pathe news clip, ‘Glass City of the Future’, darting around a model of Motopia, pointing out its features alongside (a silent) Edward Mills, as the commentator explains that the 30,000 residents of this town ‘will never know the meaning of road accidents’. Although Jellicoe had been firm that he had no site in mind, for the purposes of the newsreel audience, wanting facts, it was located on a thousand acres at Staines, Middlesex and priced at £60 million. The shimmering futurism of Motopia, on the page or on the screen, was a world away from the pragmatic realities of Basildon but the little sketchbook offers a slender connective thread between the two and what might have been – so much fun in the landscape.

A version of this text appeared in an anthology of essays published to coincide with the release of the documentary New Town Utopia (2017) directed by Christopher Ian Smith.

Notes

- Steve Parnell, ‘In Praise of Advertising,’ The Architectural Review 235, no 1404 (February 2014) , pp 108–09.