Architecture as Poetics of Knowledge. The São Salvador de Figueredo Parish Church by Paulo Providência

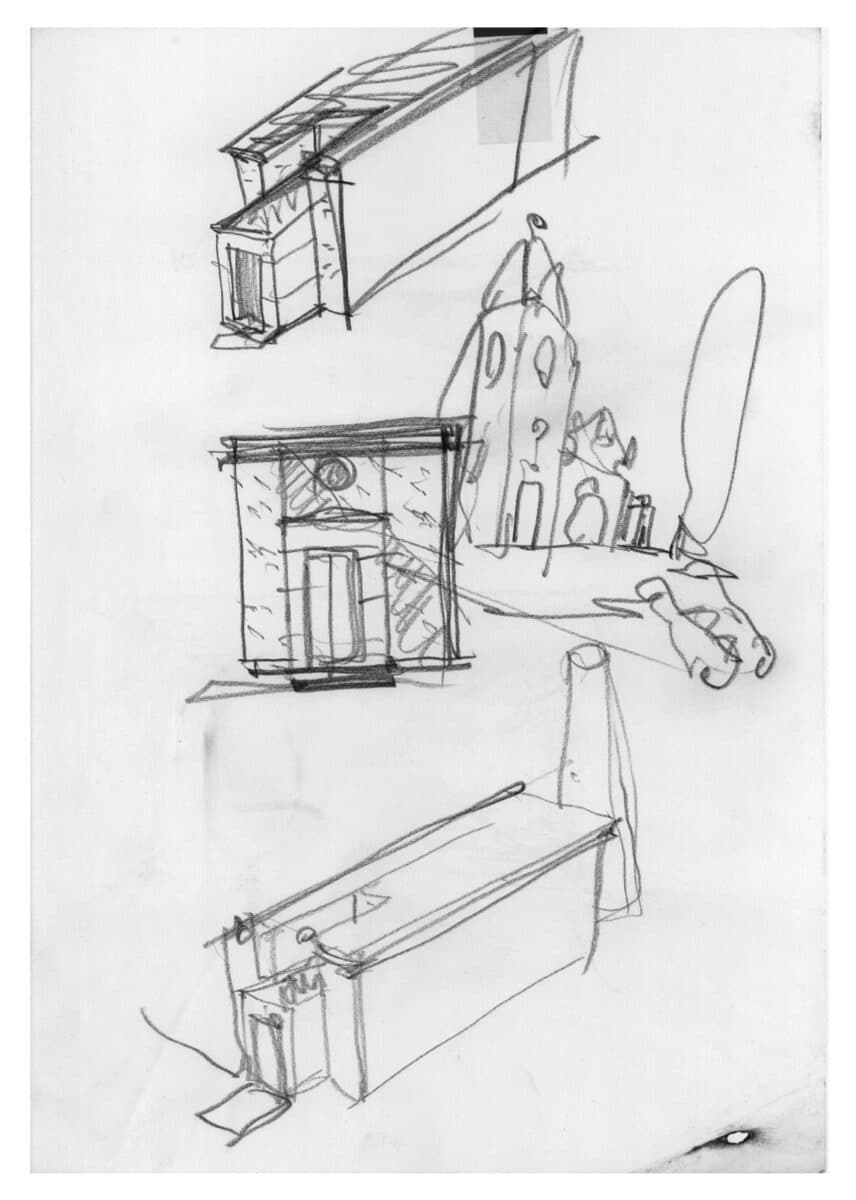

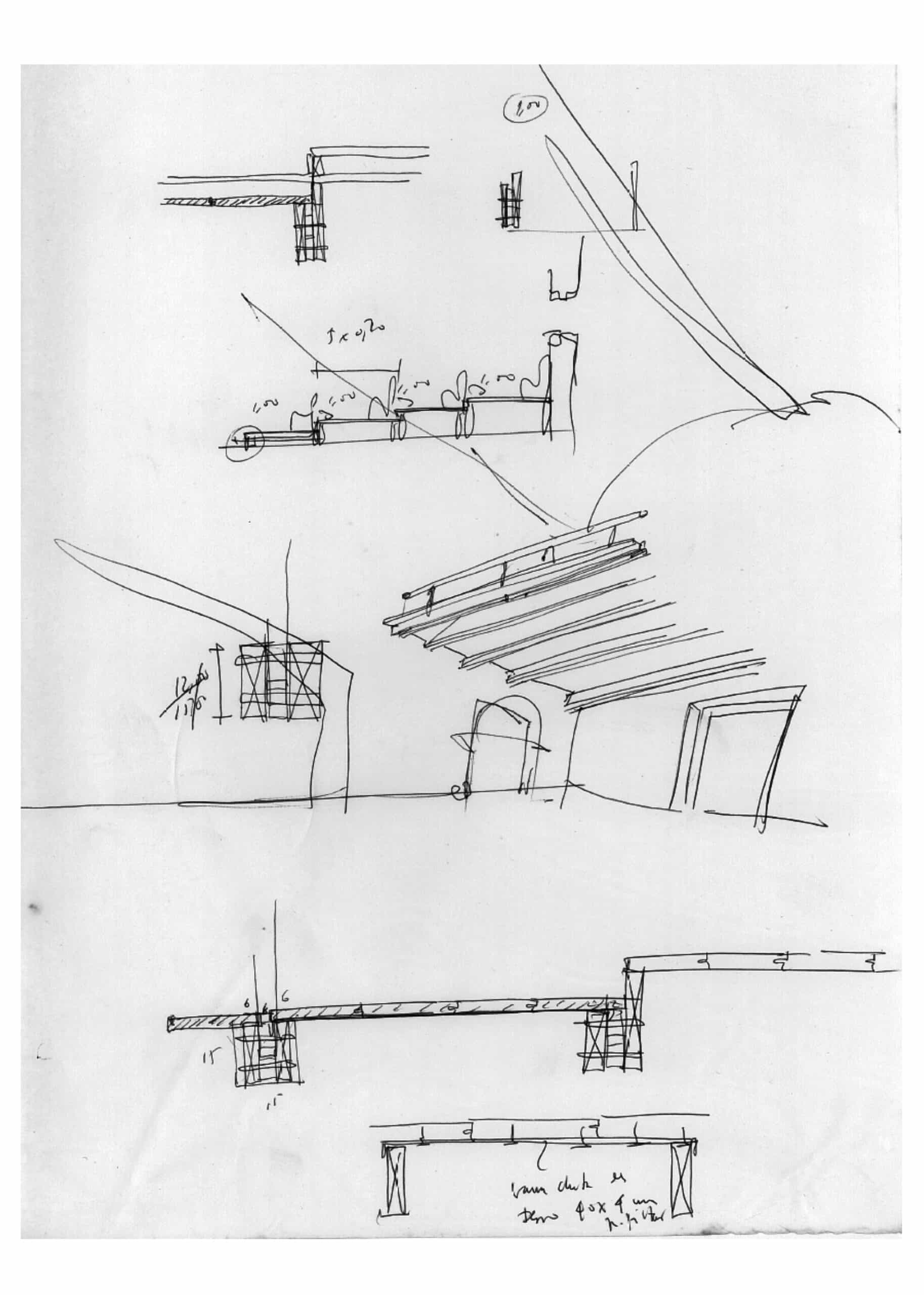

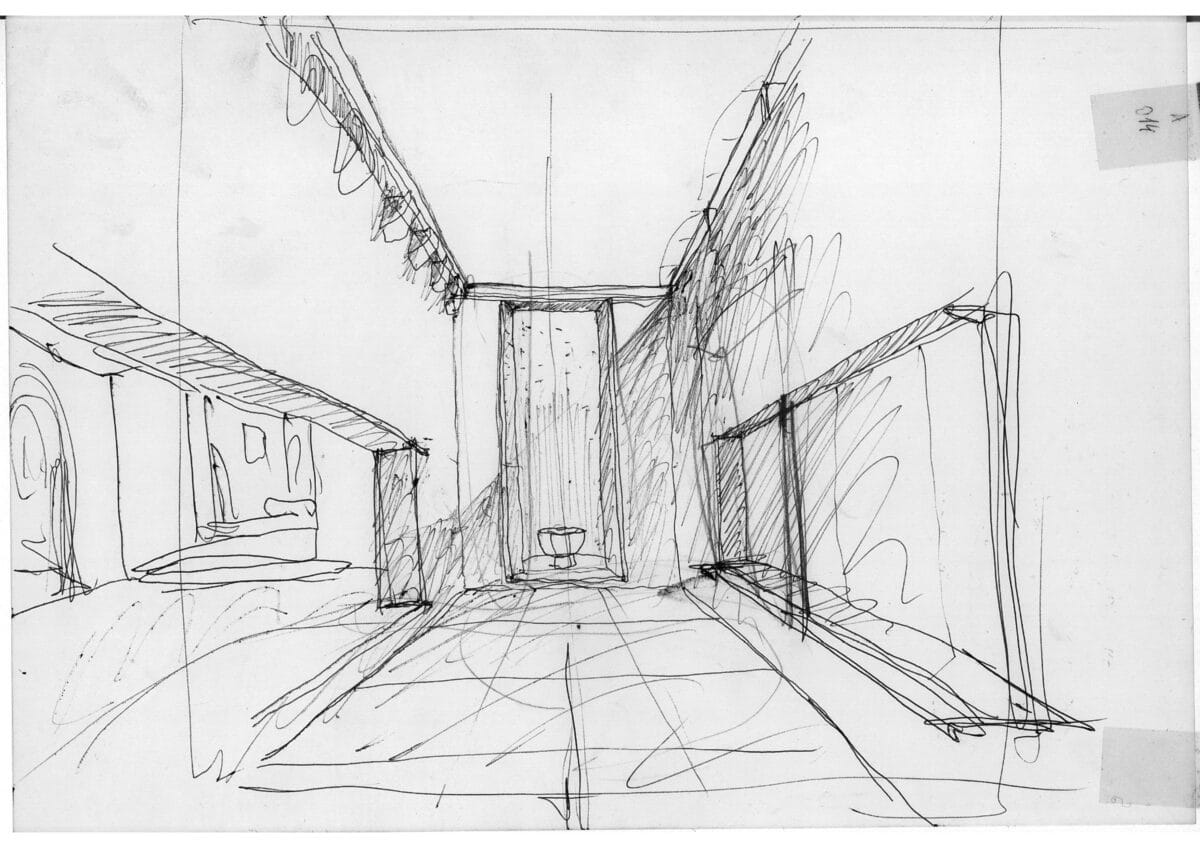

The book Architecture as Poetics of Knowledge is essential reading for anyone interested in Paulo Providência’s renovation of the parish church of São Salvador, Figueredo, 1992-2002, as well as for understanding his singular architectural poetics. A beautifully published suite of drawings (29 pages, including 4 foldouts) and photographs (34 pages) is supported by six essays, including one by Providência, which includes his vivid sketches, looking at different aspects of the project.

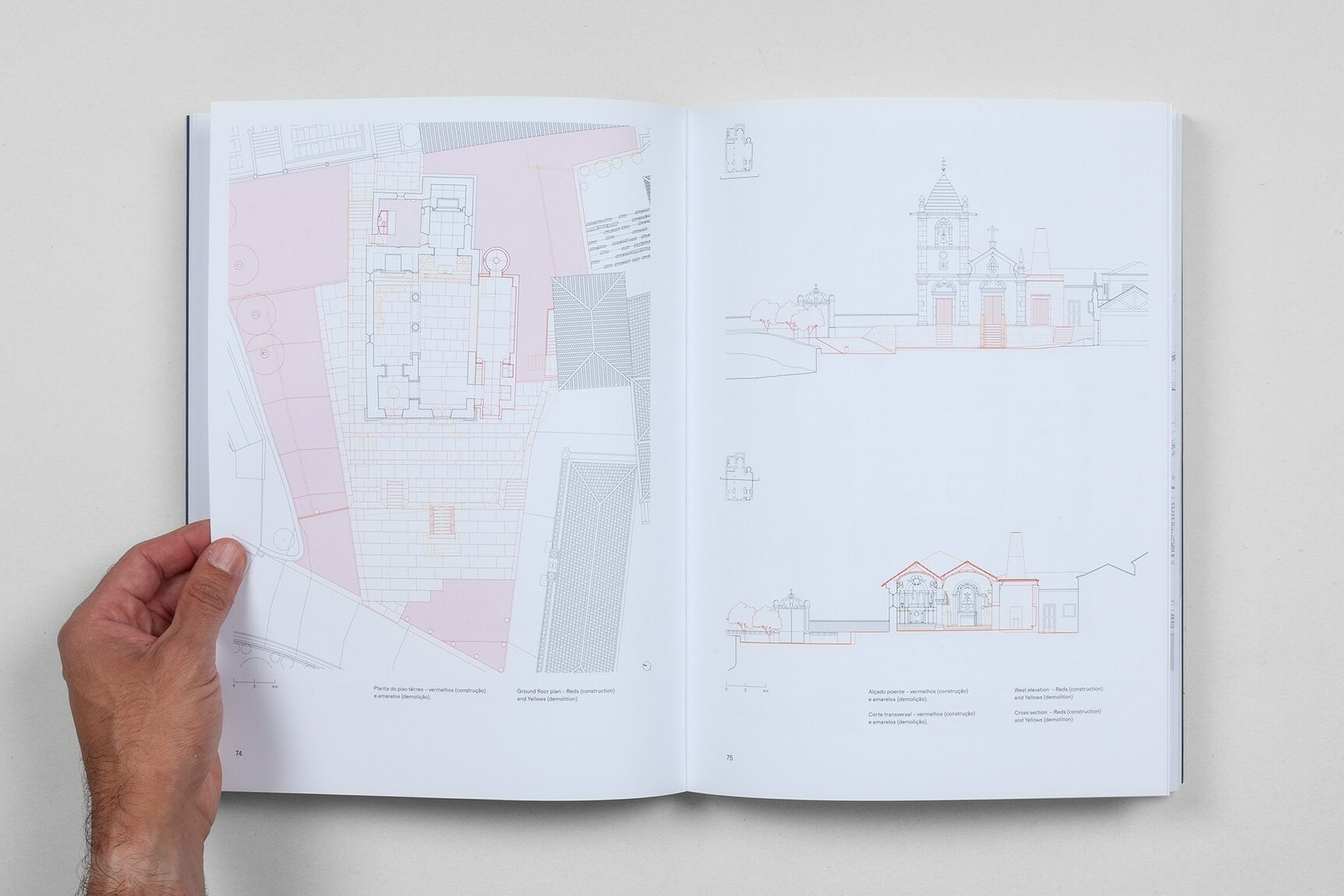

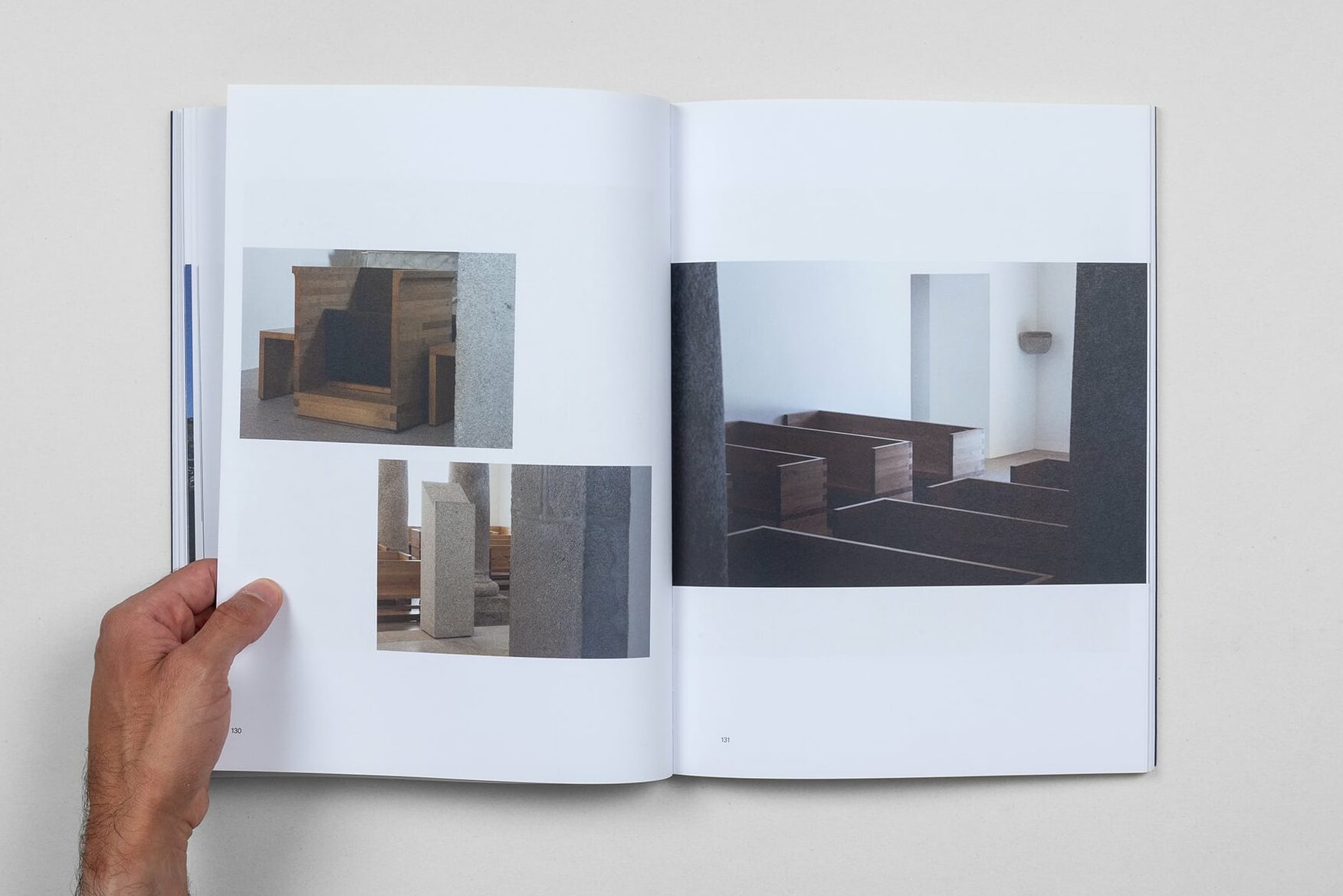

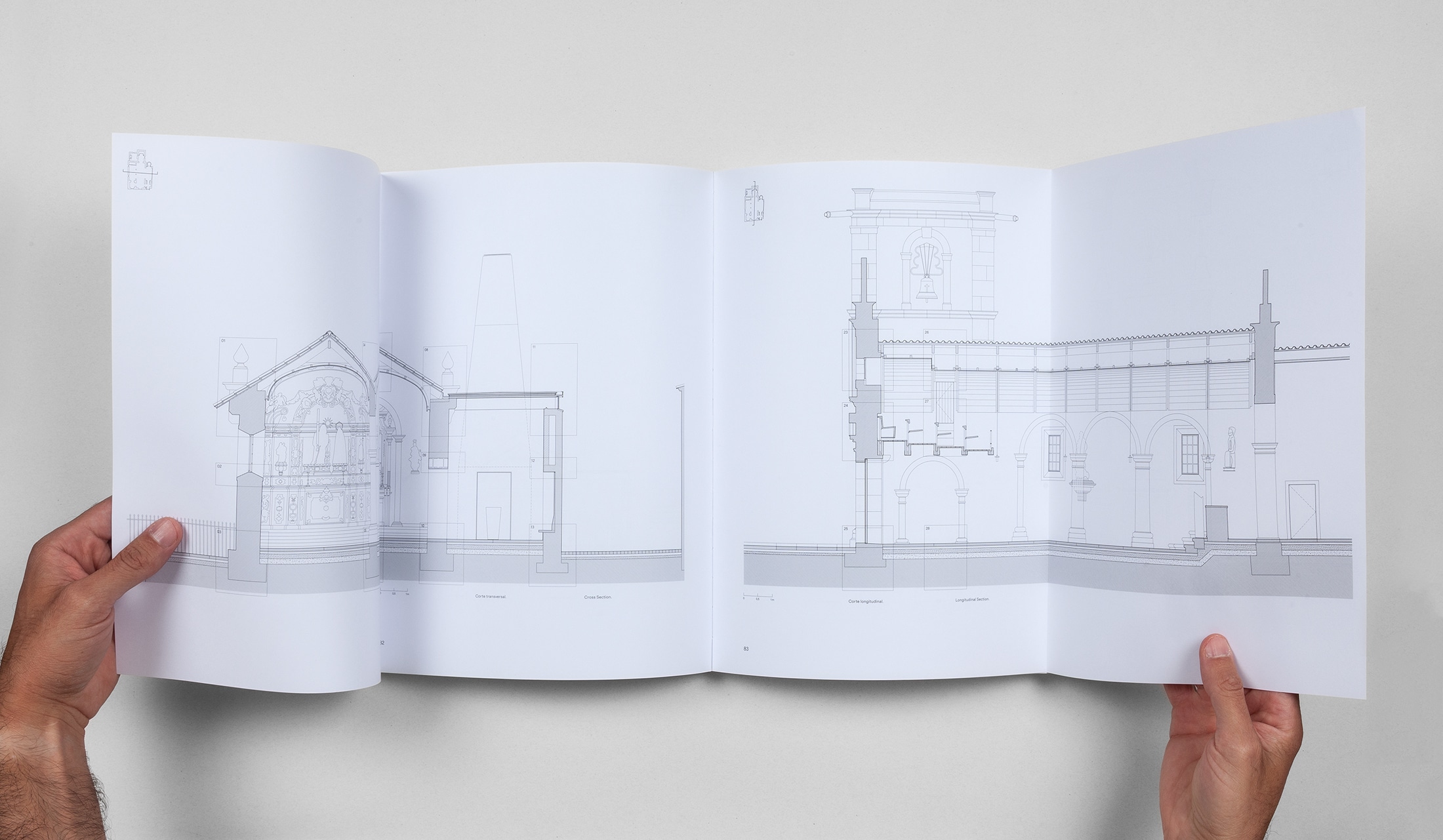

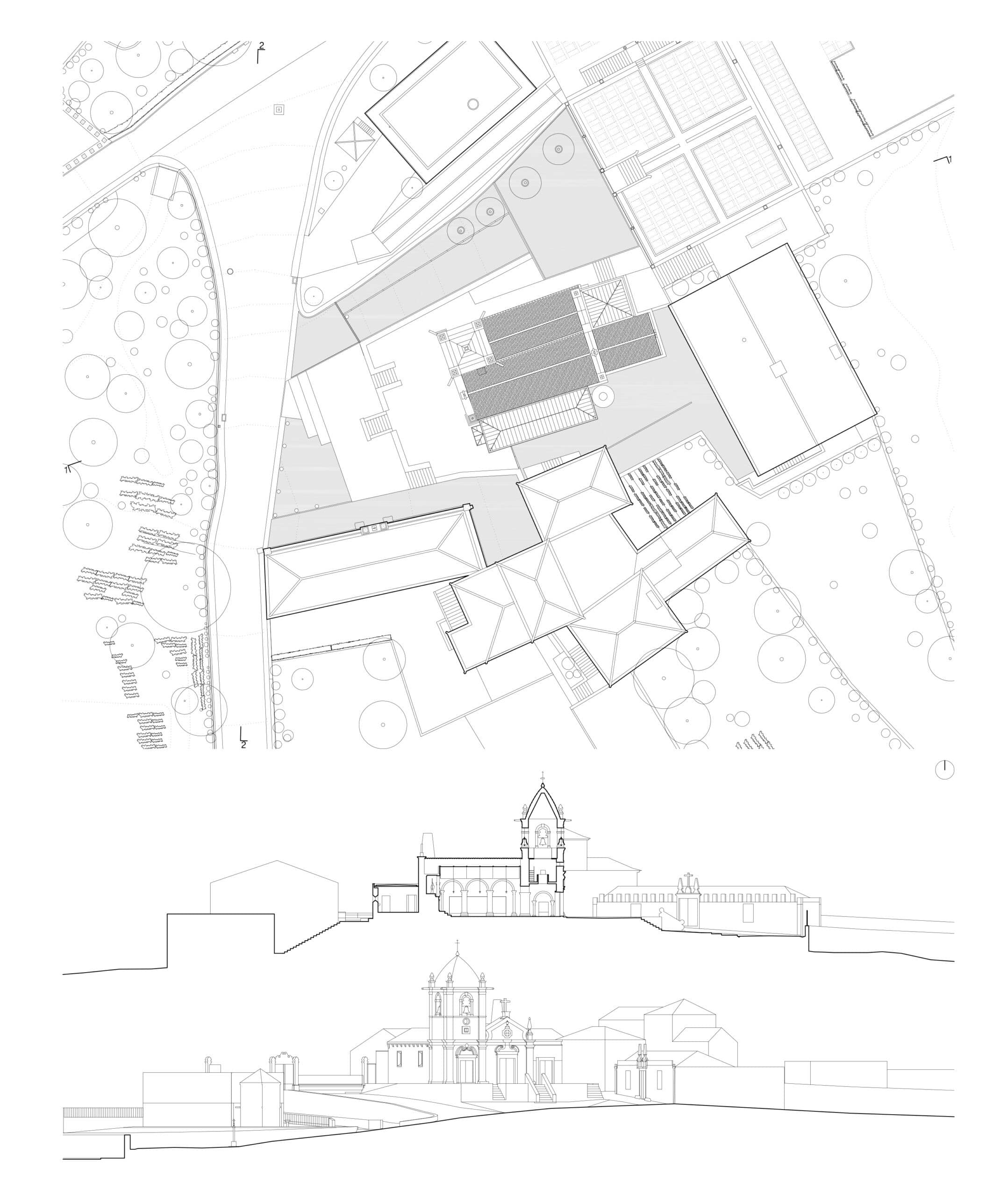

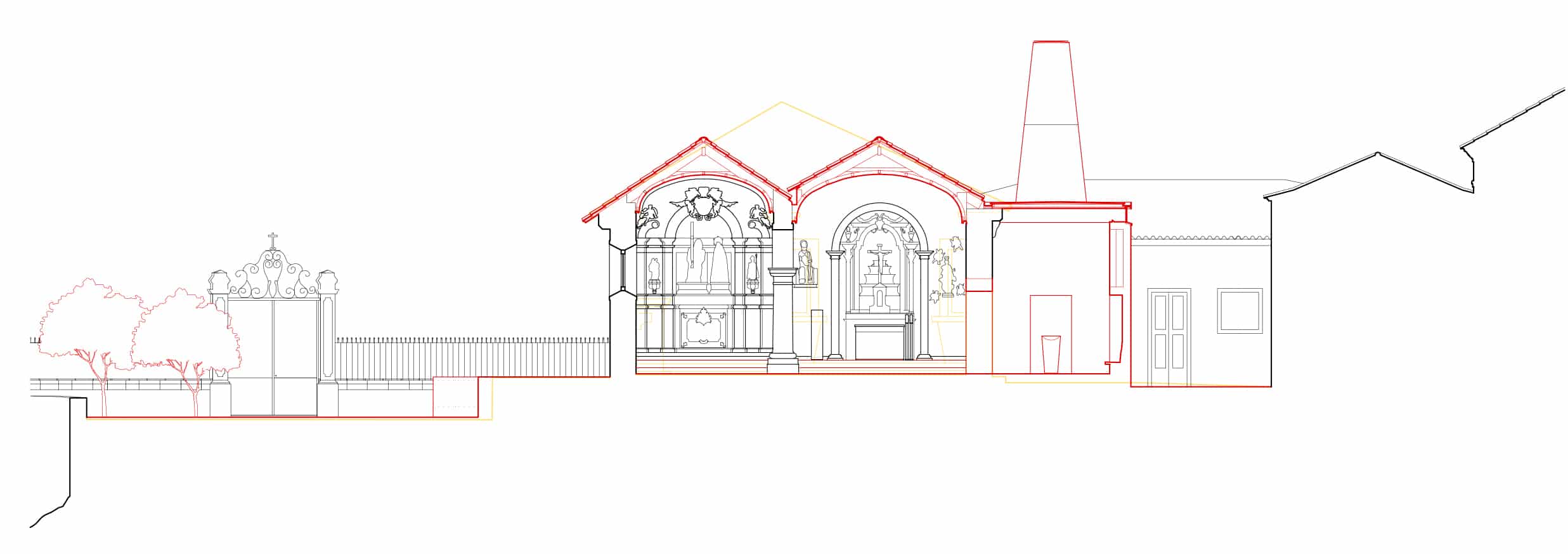

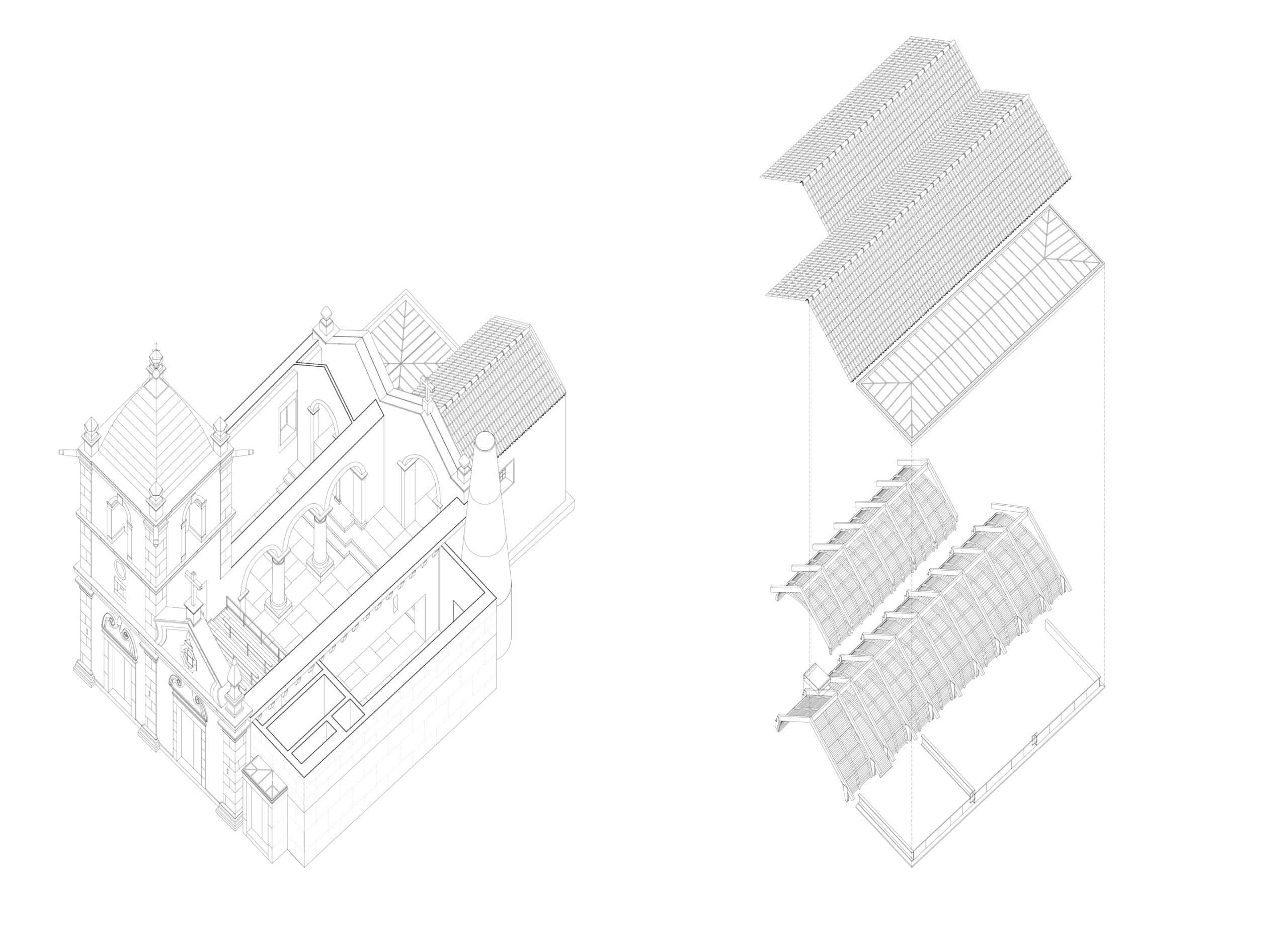

The final drawings work their way through the scales from a regional map to the local site to the architecture, and down to construction details and the furniture. They have the meticulous precision of CAD drawings, animated by the subtlety of the interventions and the character of the edifice. What at first glance appears to be an attractive addition and renovation of the existing church turns out to be a rich story of refined transformation carried out in a spirit of collaboration with not only Dr. Agostinho Alves, the parish priest, Manuel Martins, the builder and David Fernandes, responsible for the site work, but also the Works Committee and the entire congregation, who energetically raised funds for the reconstruction, and continue to provide flowers and host events.[1] The edifice gains in depth—even mystery—as the plot unfolds.

As to the basics, which took me awhile to establish, it is helpful that Google Maps allows this region of Portugal to be viewed in 3D, so that one can appreciate the position of the church atop the hill in the large valley of scattered settlements and can follow Providência’s narrative of ascent and pilgrimage, as well as his description of the relation of the church to the Casa do Hospital.[2] There seems to be some ambiguity regarding dates, but a single-nave medieval foundation was rebuilt in the 16th century. In the 18th century, a second nave was added to the south, as well as the prominent campanile and the Baroque ornament of the facade. By the mid-20th century, accumulated niches and statues of saints cluttered the interior of a church fallen into disrepair, and the site had acquired a prominent terraced cemetery. Dr. Alves had begun restoration before Providência became involved. After a decade of effort, the church comprised three naves, from north to south: a nave oriented to the original altar, now for the Reserve Eucharist; a nave oriented to the high altar withdrawn into a deep chancel; and Providência’s new third nave, with the Baptistery occupying its apse.

I am unable to recall another example of a baptistery so disposed, but it falls within the precepts of Vatican II, as Rui Machado demonstrates in his essay. Accordingly, there are three apses at the east end, each with its own light. The Reserve Eucharist altar is an elaborate gilded frame for statues of Mary and Jesus in a niche (with a smaller Mary and Child and presumably a bishop-patron to either side), illuminated by a stone-framed window in the adjacent north wall. Lit by a small south window in the chancel, the high altar comprises an aedicula harbouring a crucified Christ atop a stepped pyramid (perhaps echoing the site), seen through the Baroque arch in a blue [heavenly?] wall. The Baptistery presents itself as a white wall with an austere rectangular portal framed in thin sheets of black stone, revealing the inverted cone of the marble font, which is vertically illuminated within the tall cylinder and cone whose height corresponds to the cross atop the facade pediment.[3]

Providência mentions Le Corbusier’s chapel at Ronchamp in respect of the illumination of the font as well as inspiration from Romanesque and Mozarabic churches, which embodied an ethos also important to Le Corbusier. The essays in the book multiply references such as these—Barragan could be added—the most apt of which are derived from Providência’s Architectonica Percepta, although their accumulation does not quite capture the elusive sensibility of the São Salvador church.[4]

For example, the negotiation with history transcends the constancy-in-variation of church typology to find several temporal orders that stimulate an exchange between contingent human history and Christian redemption. This can be traced in successive transformations of the south walls, as each found itself mediating a new nave. The north wall with its two stone windows presumably remains from the single-nave 16th-century church, whose south wall became an arcade of stone Tuscan columns and piers with the 18th-century addition of the high altar nave. From the 18th-century south wall, Providência carved a great opening beneath a doubled I-section lintel, in order not to obstruct views of the high altar and lectern from his Baptistery nave. The south wall of the Baptistery nave does not reach the eaves, but supports an alabaster strip window corresponding to the fascia of the facade entablature. Excavated within this wall is a large niche matching the opening in the 18th-century south wall opposite. The niche accommodates seating, and this literal inhabitation of the wall sets off resonances with all the other framed openings, some of which one occupies bodily, like the oak pews or the portals, others imaginatively, such as the window left in the 18th-century south wall. It is as if the Baroque facade articulation had metamorphosed within the rhythmic box of the church, creating a milieu that, with the judiciously distributed statuary, communicates between human and divine according to ensembles of allusive histories or narratives governed by those of the three apses.

This, of course, is only one—very partial—way to interpret this compelling and enigmatic building, but perhaps it is sufficient for considering ‘architecture as poetics of knowledge’, which titles both the book and the initial essay by the editors, Armando Rabaça and Bruno Gil. The phrase addresses a phenomenon characteristic of architecture schools in universities after the last World War: architects raided the sciences and the humanities for motifs and methods, but none of these disciplines came to architecture—as if architecture always needed understanding, but was not itself a vehicle of understanding. For Rabaça and Gil, typology and constructional intelligence provide the basis for a baukunst embodying a ‘logos of making’. For Providência, drawing on Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘Excavation and Memory’, the material-cultural context and the work of analogy ‘establish the exact location of where in today’s ground the ancient treasures have been stored up.’[5]

By way of accounting for the proximity of the Eucharist and baptism in the east wall, Machado begins with Romano Guardini’s assertion that ‘water, light, the cross, oil and white robes’ have an intrinsic symbolic value whose concreteness and immediacy animates a ‘poetics of sensation…a baptismal mystagogy’. The founding rites of Christianity—both of which involve fellowship, death and rebirth—are consequently suspended between two millennia of theology and a more open field of references made coherent in liturgical performance. Not everyone will be able to reconcile Machado’s occasionally ecstatic mystagogy with the decorum of the church—the allusion to a Morandi still life by Hatz seems more apposite—but the dialectics of liturgical conformity and mystical speculation, like the new disposition of the baptistry, have the capacity to rescue profound themes from unreflected adherence to ancient ritual.

In any case, what the church of São Salvador embodies is less knowledge of something—perhaps the exchange between tradition and innovation—than a wisdom, an orientation in reality. There is no better word than ‘poetics’ to account for the manner in which architecture reconciles situations, nature, materials, technology with ethics. Indeed this form of synthesis differs considerably from Enlightenment knowledge protocols—for one thing, it is particular and situated, not a general concept—and ought to be instructive for communication among the myriad specialist disciplines, that is, between the sciences and humanities. Accordingly, Providência rightly argues that architecture qualifies a concrete context, which is an embodied cultural heritage long before it is ‘forms’, in this case cultivated within centuries of Roman Catholic custom. For those who are neither members of the local congregation nor have had the opportunity to visit São Salvador, close study of the suite of drawings and photographs in this book will be the measure of all possible words about the church and will be the basis for appreciating the judgements, at once both subtle and radical, of its genuinely gifted architect and his collaborators.

Notes

- See Sandra Xavier’s essay in Paulo Providência, Architecture as Poetics of Knowledge. The São Salvador de Figueiredo Parish Church by Paulo Providência, ed. by Armando Rabaça and Bruno Gil, trans. by Dave Tucker and Rita Caetano (Coimbra: e|d|arq,2024), 194-205.

- Enter ‘Igreja de Figueiredo’ and select the correct church from the drop-down.

- These sheets extend into the Baptistery beyond the thickness of the wall, enabling an uplighter to be hidden above the soffit.

- Paulo Providência, Architectonica Percepta, texts and images 1989-2015 (Zurich: Park Books, 2016).

- Paulo Providência, Architecture as Poetics of Knowledge, 53.

*

Peter Carl received his MArch from Princeton in 1971 and the Prix de Rome in 1974. He has taught design and graduate research at the University of Kentucky (for 3 years), the University of Cambridge (for 30 years), and London Metropolitan University (for 7 years), and has held visiting positions at Rice University, University of Pennsylvania, Cornell University, and Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is currently studying metaphor and embodiment as the basis for the architectural poetics by which situations are reconciled with technology, ethics, mood, reference, etc.

Paulo Providência holds an Architecture degree from the University of Porto (1988) and a PhD from the University of Coimbra (2007). A practicing architect with an interest in the design of public-use buildings. He runs a design studio at the University of Coimbra, bringing heritage and architectural discussions outside the institutions, through public debate. His research interests include nineteenth-century and contemporary methods and practices of architectural design, and the architecture of public health facilities.