Branzi, Observed: Autocatalytic, Earnestly Jaded

Andrea Branzi died on 9 October 2023 aged 84. The impact of one of his seminal works, No-Stop City, has been felt far and wide within architectural discourse. Since its production between 1967 and 1972, the drawings and collages of No-Stop City have haunted the camps within architectural academia that have sought to recover a leftist political agenda from the fragments of modernity.

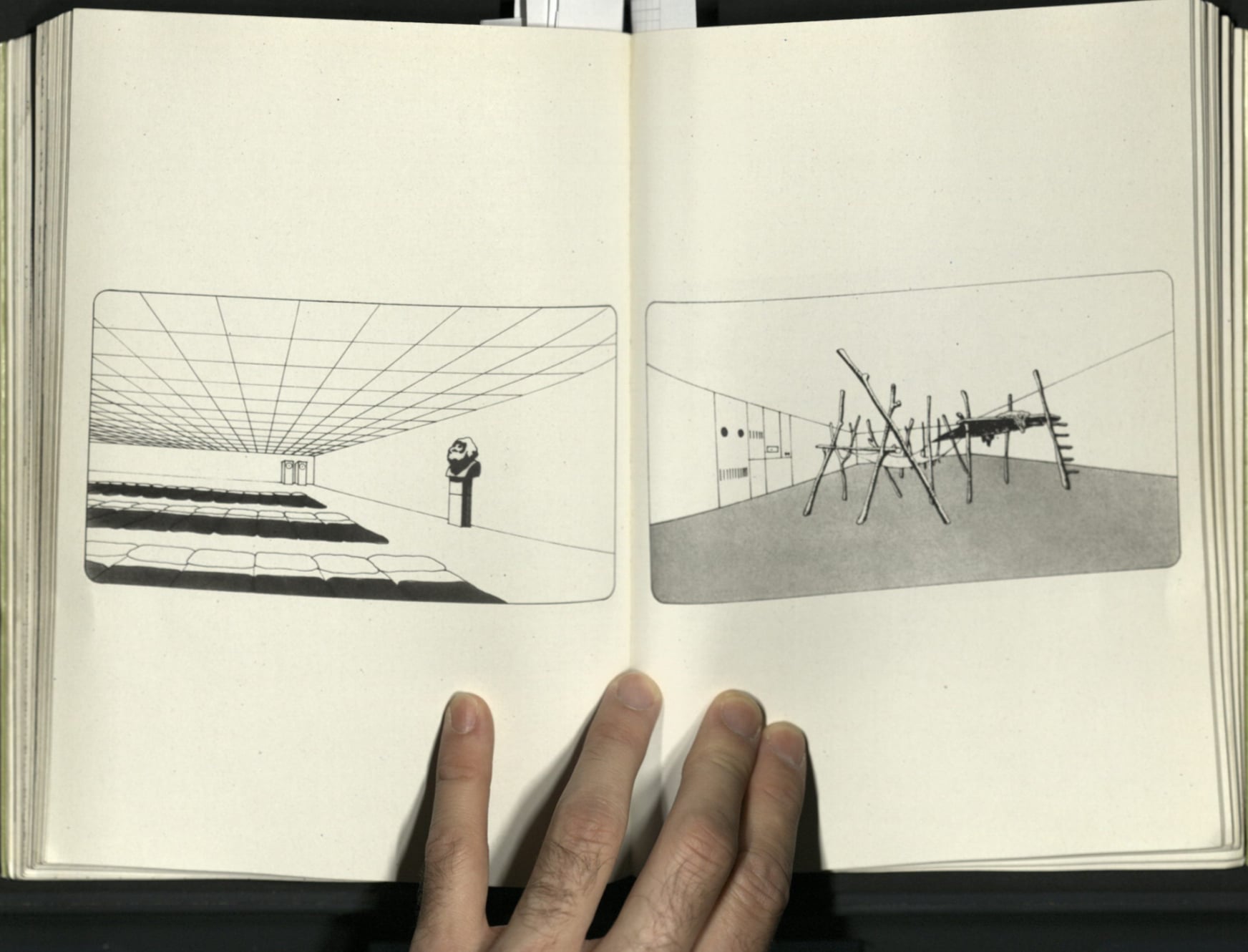

One such image has been particularly meaningful to me: a perspectival drawing found in Archizoom’s No Stop City monograph.[1] The drawing is one of a series of dreamt-up interiors of residential parking garages, coming in sequence after plans at different scales showing the endless blanketing of terrain by the grid. Floating in a sea of nodal points of essential, minimal life—beds and toilets as previously articulated in plan—we come across the boxy depictions of the life suffused within. Archizoom took the work of Ludwig Hilbersheimer, critiquing what was a noble intention but ultimately an inhumane rendering of the individual as the universal urban subject, with the outcome landing somewhere between absurdity and woe. Witnessing the instrumentalization of architecture as a tool in postwar capitalist development (unfolding differently in the United States and Western Europe), Archizoom sought to attack what they saw with an ironic gesture at what remains for architecture to do—namely, to populate rooms. Architecture is merely the elements that were to characterize universally air-conditioned spaces. It was a cynical, non-figurative rendering of the city as a figurative result of the infrastructures that enable the reproduction of labour.

Like many of their other perspectives, this one is done in greyscale, with a predominance of line and fill. We are situated in the foreground of a large room. The room is expansive, especially in comparison to the squat ceiling clearance. Situated almost at the centre of the frame is one of the rear corners of this room. The room continues out of frame to the left of the drawing, suggesting an infinite continuation. In the room are situated three distinct elements—what the eye is drawn to first is a bust of Karl Marx, sitting at the midpoint of the right-hand wall, characterized by a dark poché (it is unclear what lighting source is casting the shadow). To the left of this sculpture sit three rows of sleeping bags, lined up side-by-side. Curiously, though, there is no one cozied up within these bedrolls: they all lay flat and immaculately prepared. In the background, at the corner point, sit two objects along the back wall, gazing longingly, each with their single eyes, towards the bust of Marx. The icon of Marx is the focal point of not only our gaze but of the architectural life represented.

It is interesting to me that this sequence is drawn in perspective, as opposed to the more iconic images of the theatres drawn in a sharp axonometric. These perspectives evoke a similar attitude towards infinity and the visible end of the knowable world that their peers Superstudio often used. In a tongue-in-cheek way, though, Archizoom does not continue onto the horizon: instead, the infinite is to the left of the drawing, as both the ceiling panel grid and the rows and rows of sleeping bags continue out of frame. The horizon is denied to us. Instead, we are shown what happens when universal infrastructure spreads out sideways: endless rolls of temporary beds, waiting for their troops, and the sculptural totem that watches over them while they sleep. Is the architectural performance, then, the subjects of the No-Stop City, the militant and organized leftist youth? Or Archizoom themselves? Why have they not arrived yet? Why are we waiting for them? The scene is certainly set for their needs, though, because what could be more disruptive to production (and more importantly, architectural production across both industry and academia) than sleep? Pervasive and universal rest.

Archizoom has been criticized as theoretical in an age of action, and it certainly does not help that they draw in a cartoonish way. Materials are abstract, with little to be discerned of any textural qualities. This was the point though: from the ivory tower of academia, they sought to use a project as a mode of political praxis, by incorporating pop culture into architectural criticism. The cultural moment—that of ’68—was a moment of great unrest and civil disobedience, especially in the US, at the threat of vast social inequality, formerly legal racial segregation, and an ever-privatizing public realm. I think what is so timely about this project, and this image in particular, is its ability to recognize the absurdity of the structure that created it—in this case, architecture school—and to co-opt its own language to articulate a stance that was both earnest and ironic. It was a form of multiplicity, the willingness to act as a double agent. To go to school, enjoy it, and still be critical.

A problem with embodied, earnest irony is the risk of the self-collapsing into this masque. The contradictory conditions depicted in No-Stop City could be considered a maximalist thought-exercise in the lineage of Hilbersheimer: Metropolisarchitecture taken to its logical conclusion. However, in expressing their earnest jadedness, Archizoom and Branzi hold a mirror up to architectural discourse for it to see its duplicitous nature. It is a response in earnest to an earnest attempt to envision utopia. It was stark realism, an acknowledgement of the failures of architecture to bring about a better society without abandoning the hope, wonder, and joy that architecture can evoke.

In memory of Andrea Branzi.

Julian Escudero Geltman is an architectural designer, critic and educator, based out of Boston where he teaches studio courses at the Wentworth Institute of Technology, collaborates with MIT’s Critical Broadcasting Lab, and practices as co-founding principal of AGONY, Architecture Group of New York.

This text is one of the selected responses to the Open Call: Storytellers, Observed—an inquiry into the origin and circumstances of a single drawing (or series of drawings), observing the ways by which each achieves the specific purpose for which it was made. For further information click here.

Find more drawings by Branzi and Archizoom on www.drawingmattercollections.com.