Broadcasting Norwegian Time

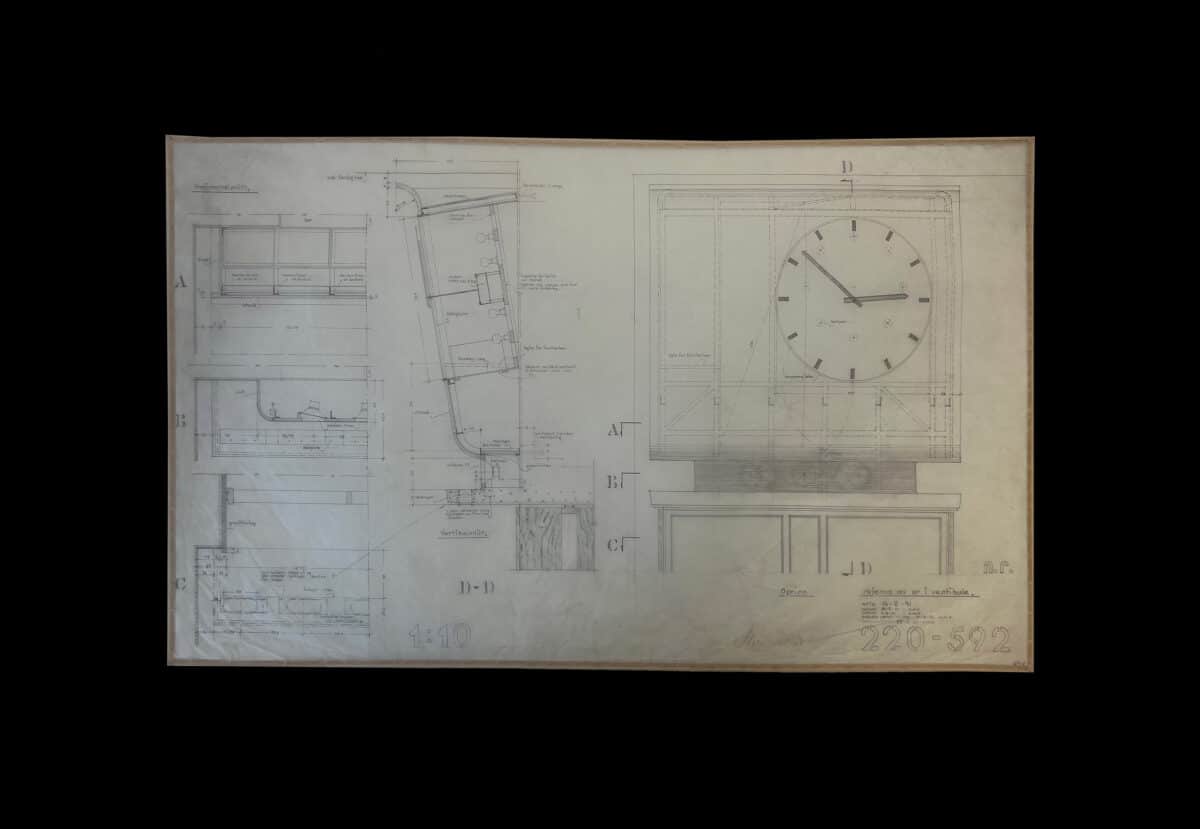

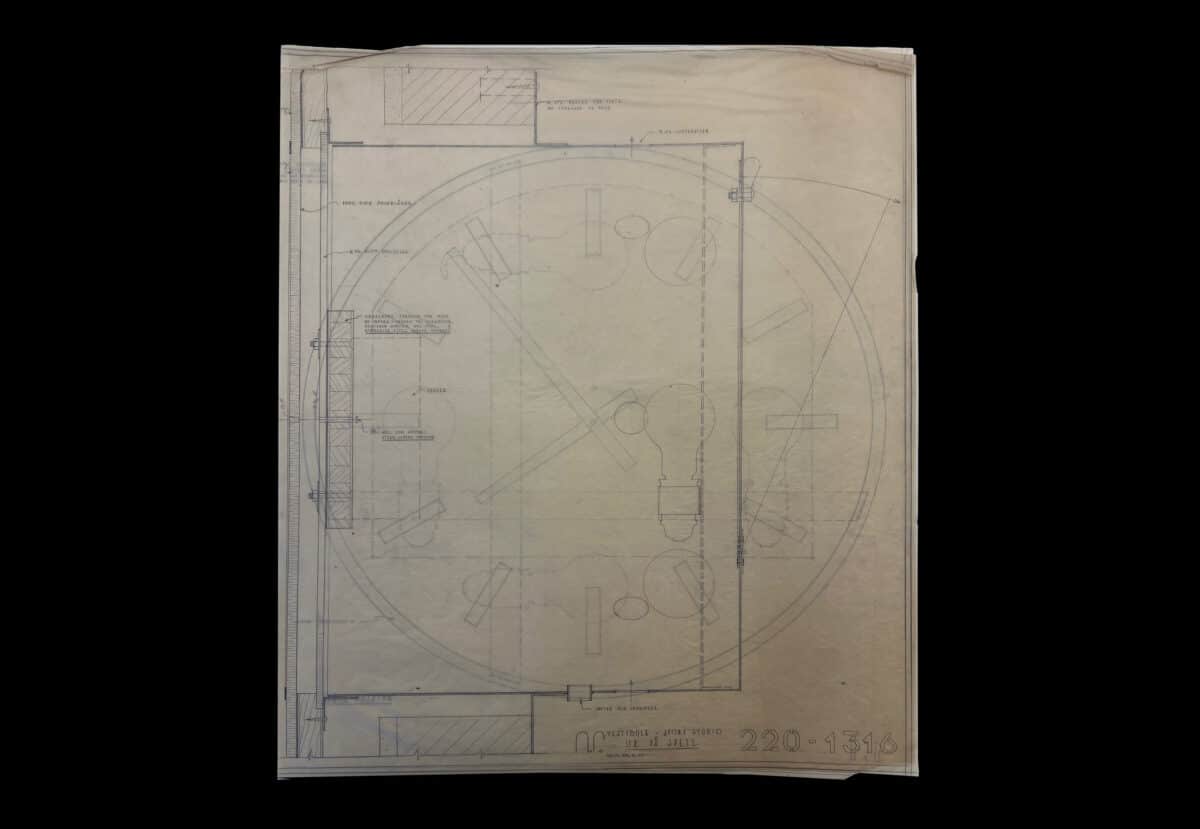

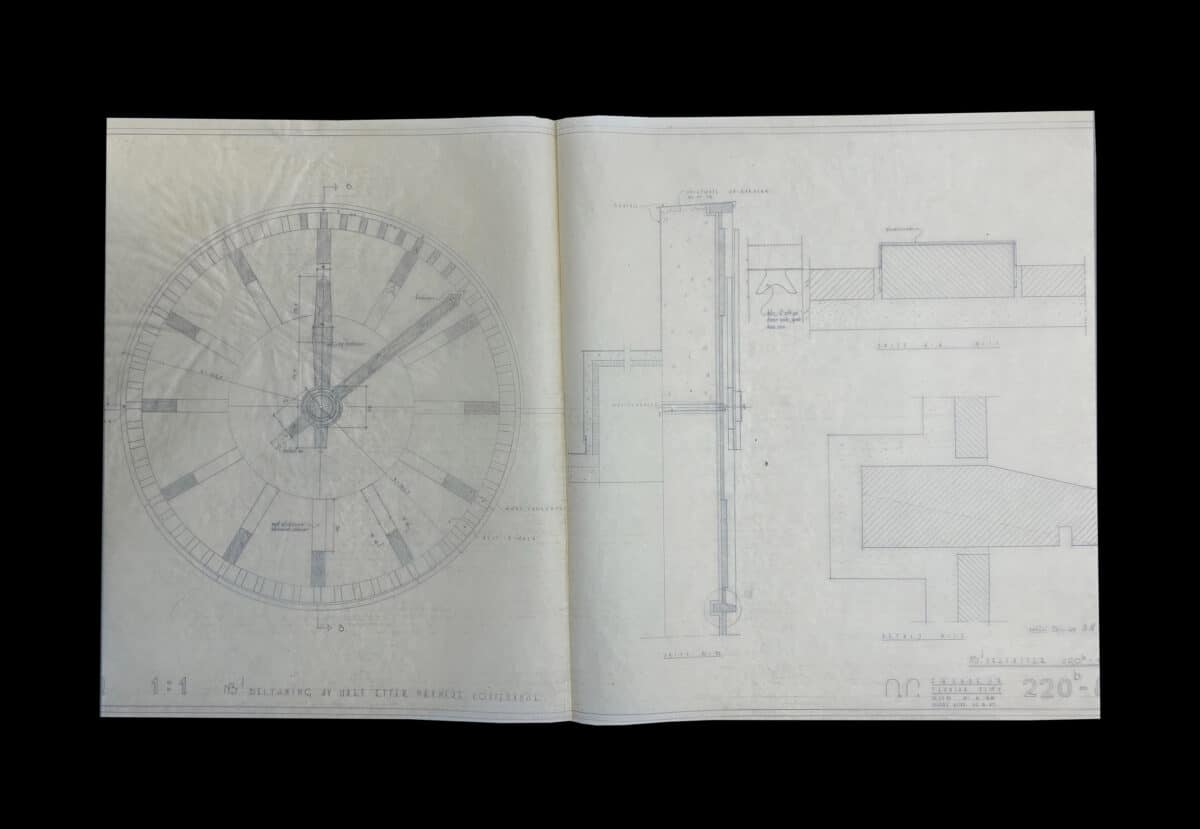

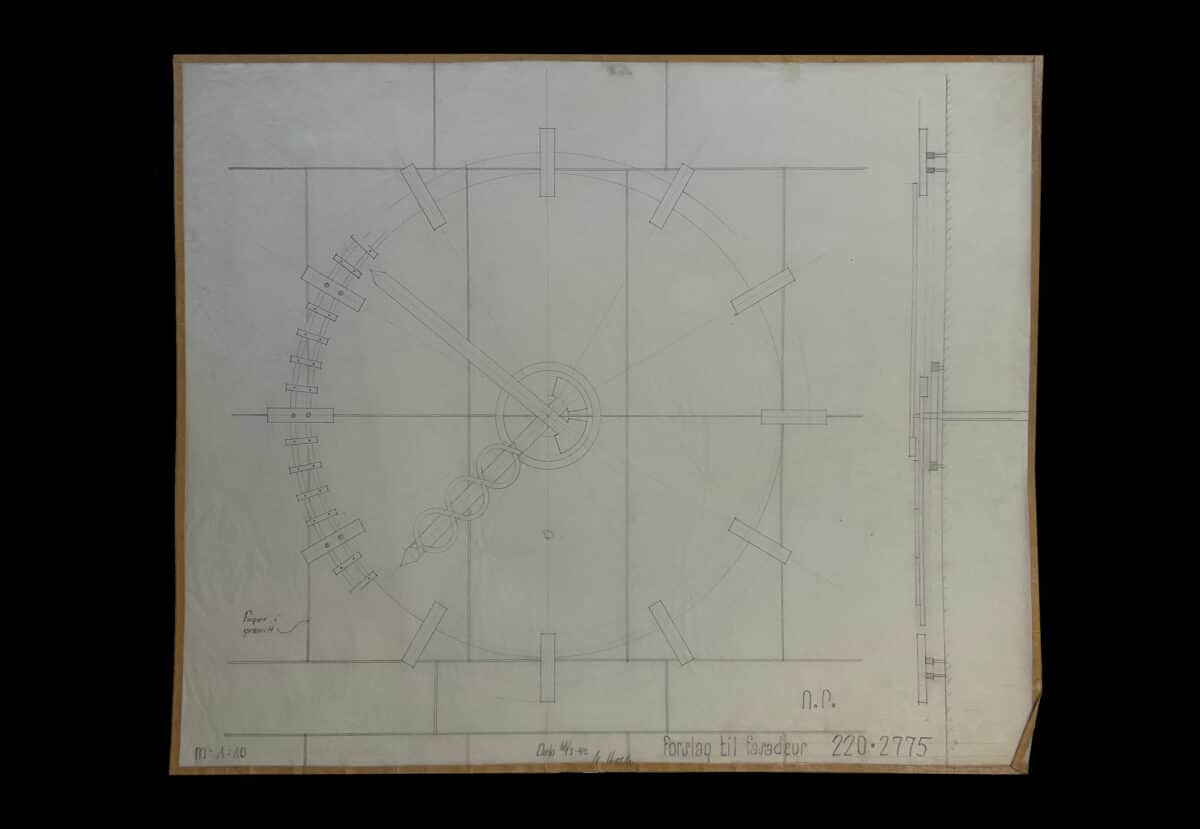

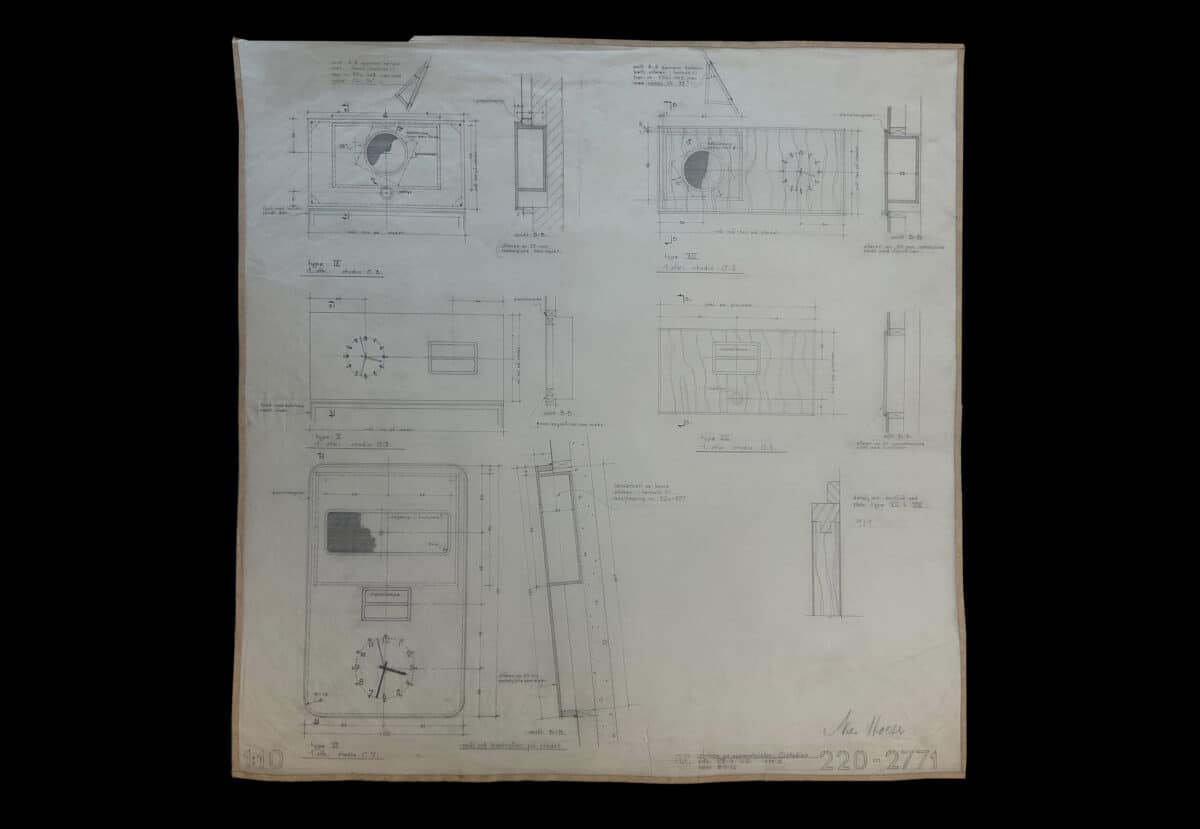

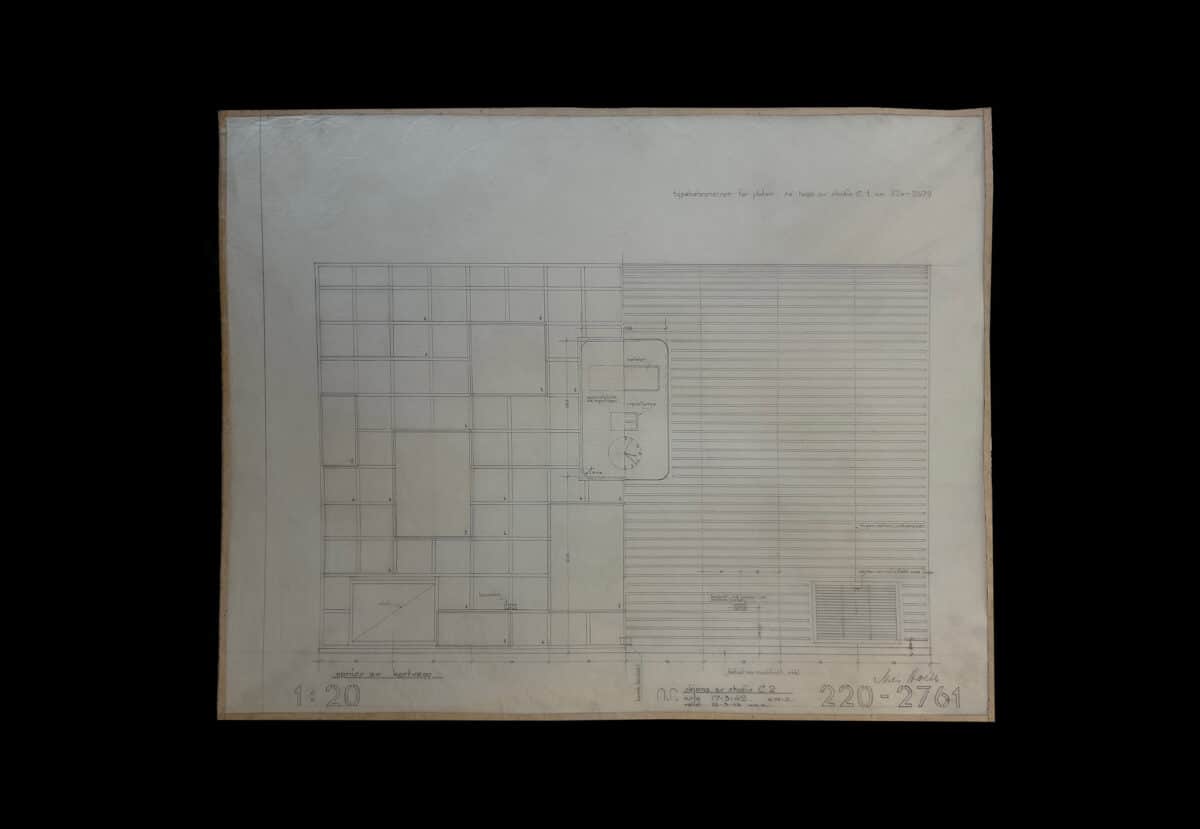

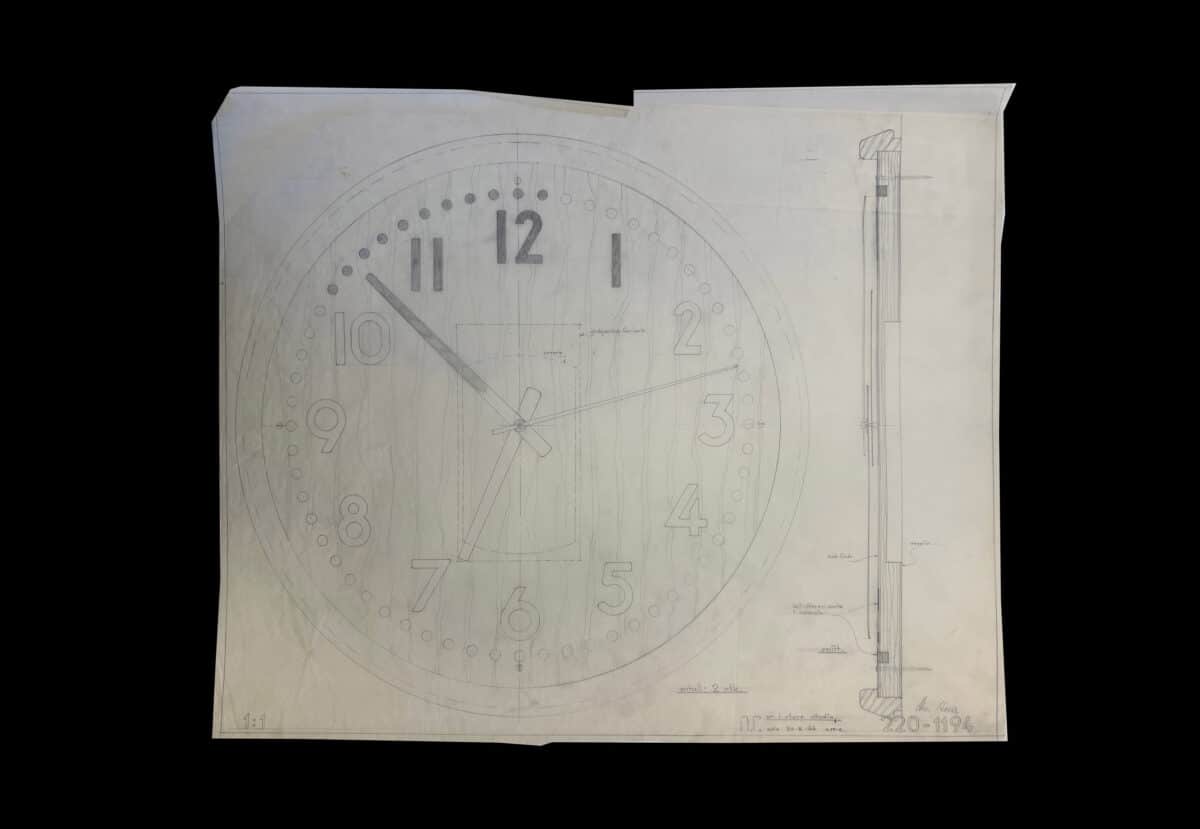

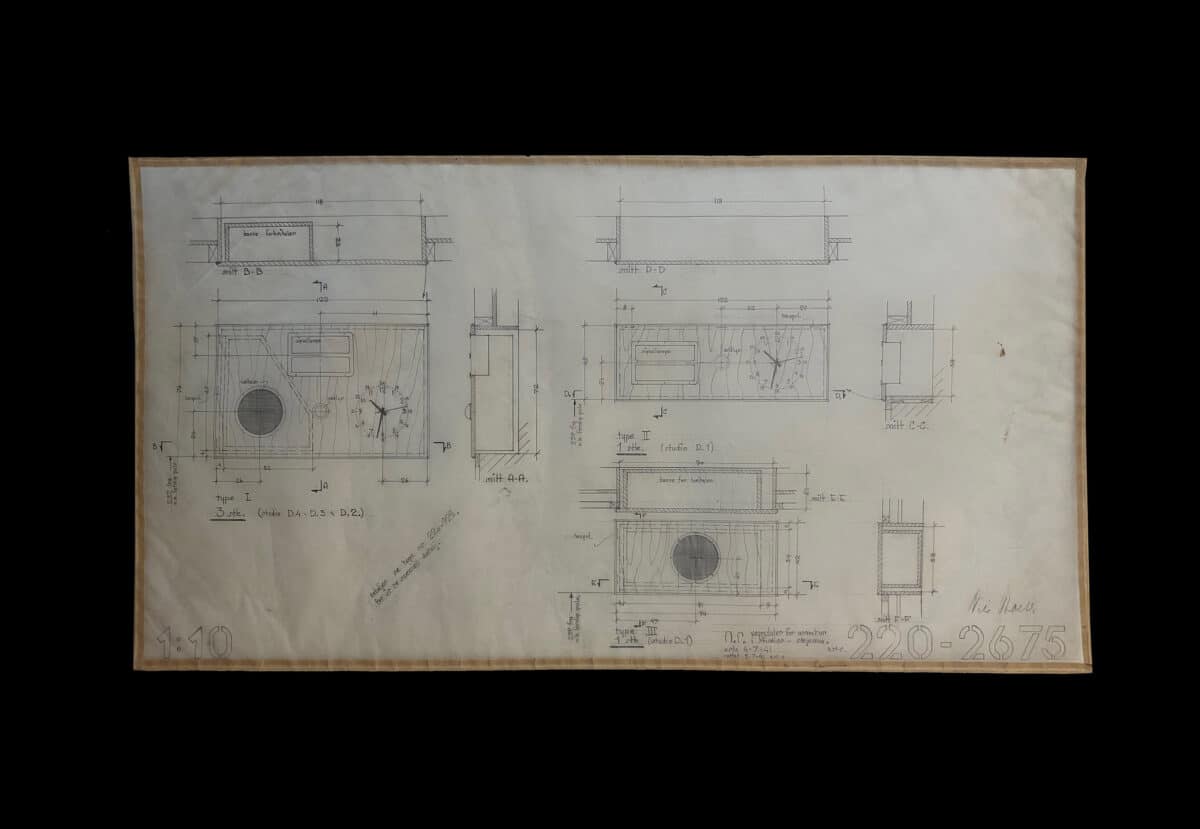

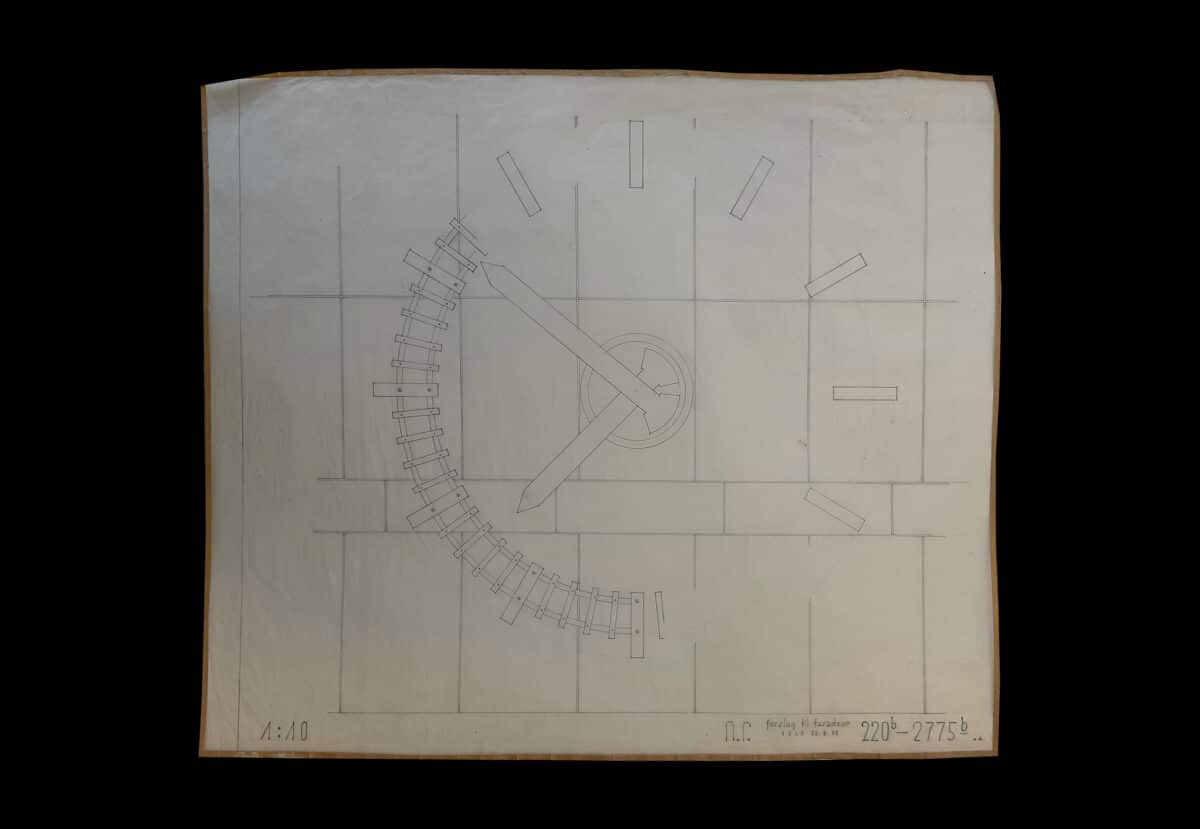

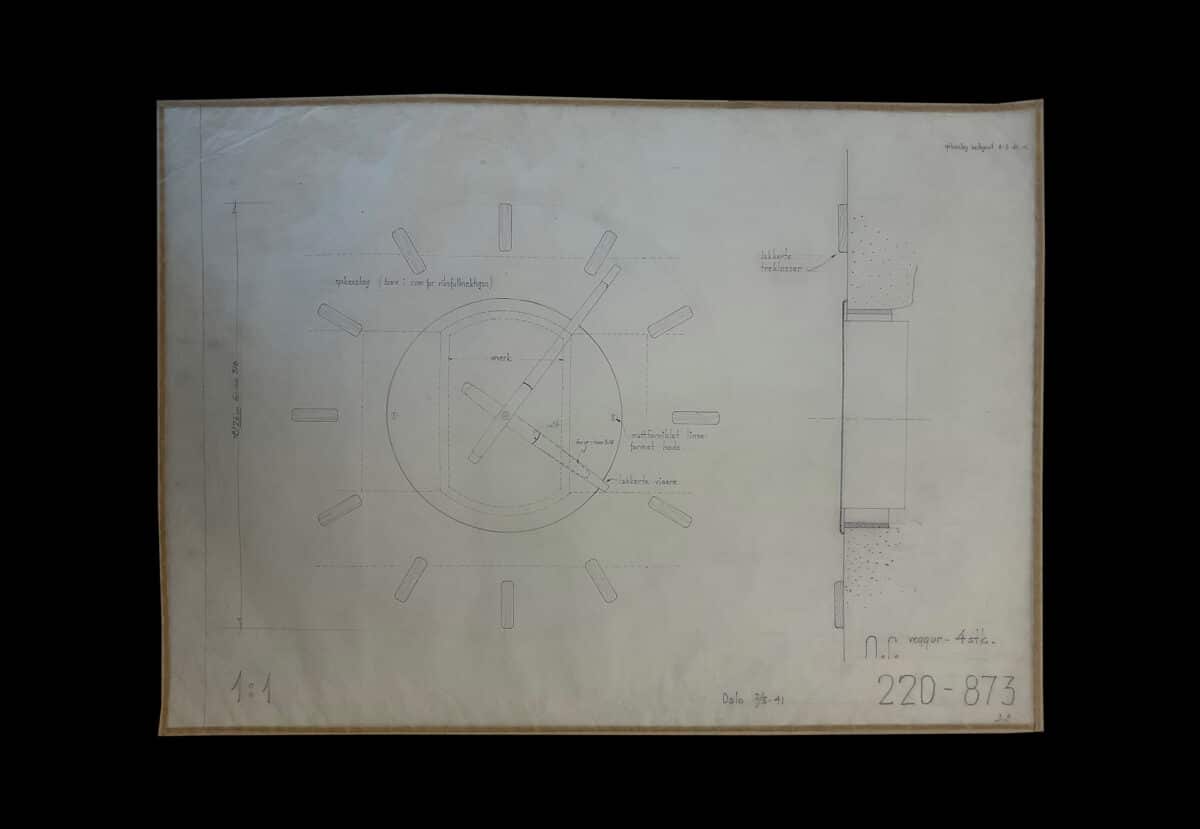

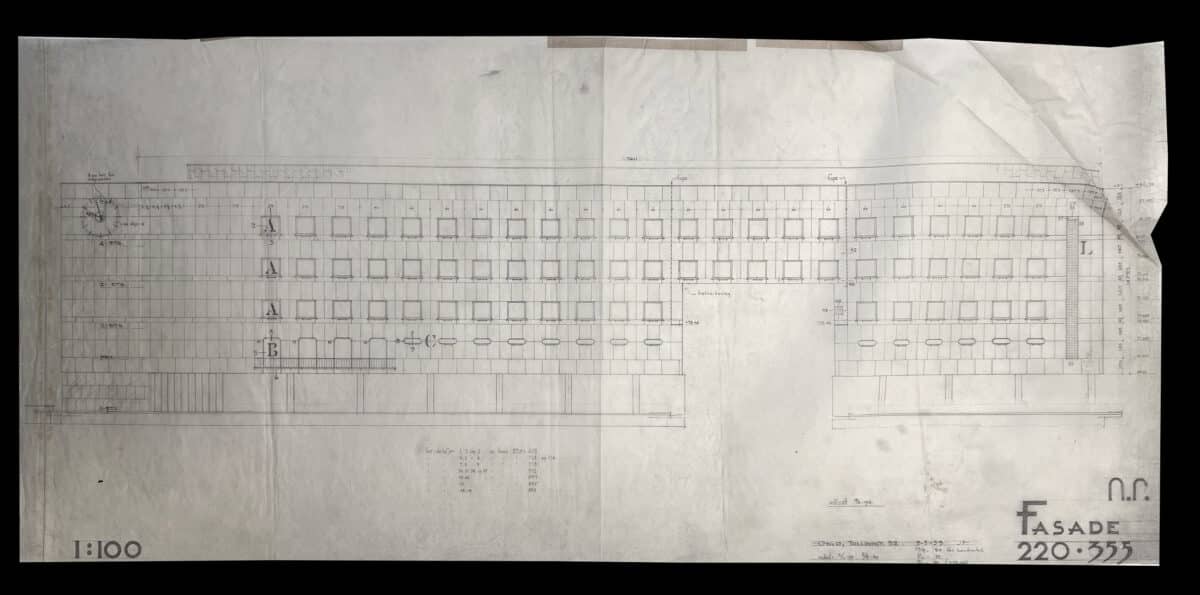

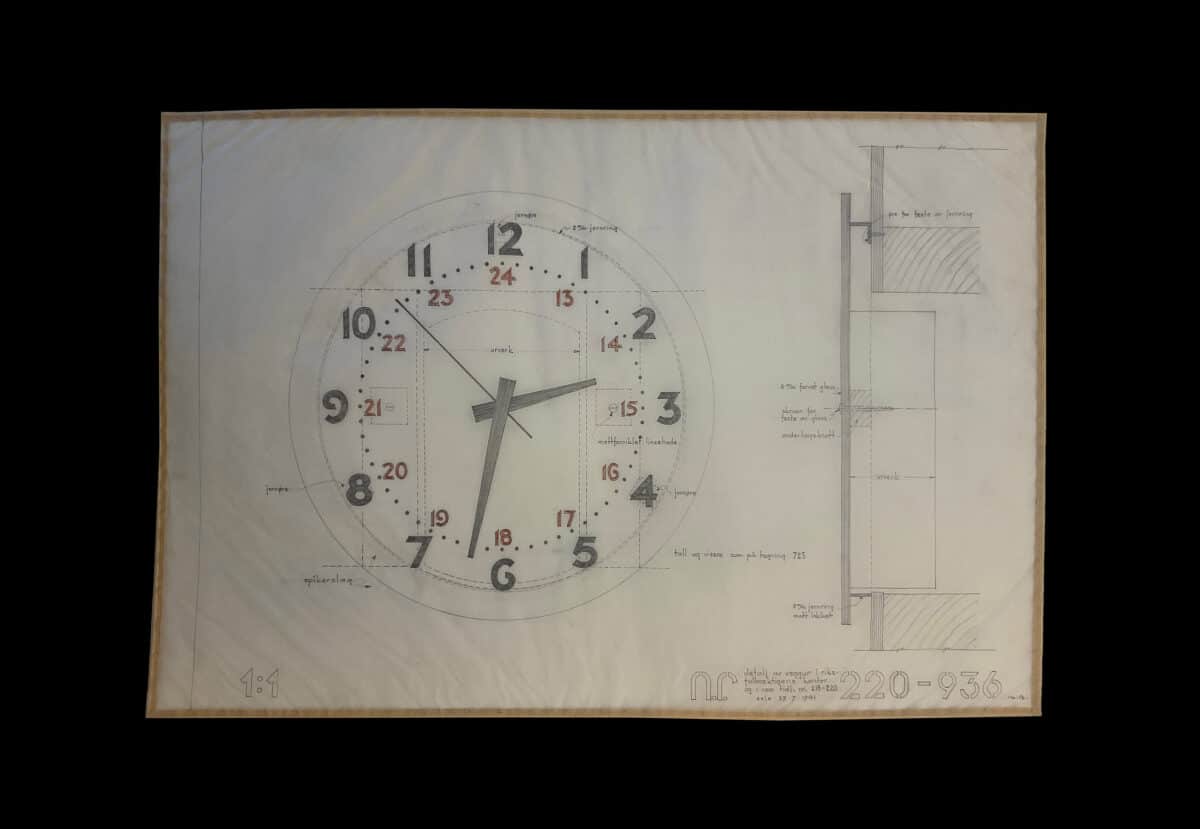

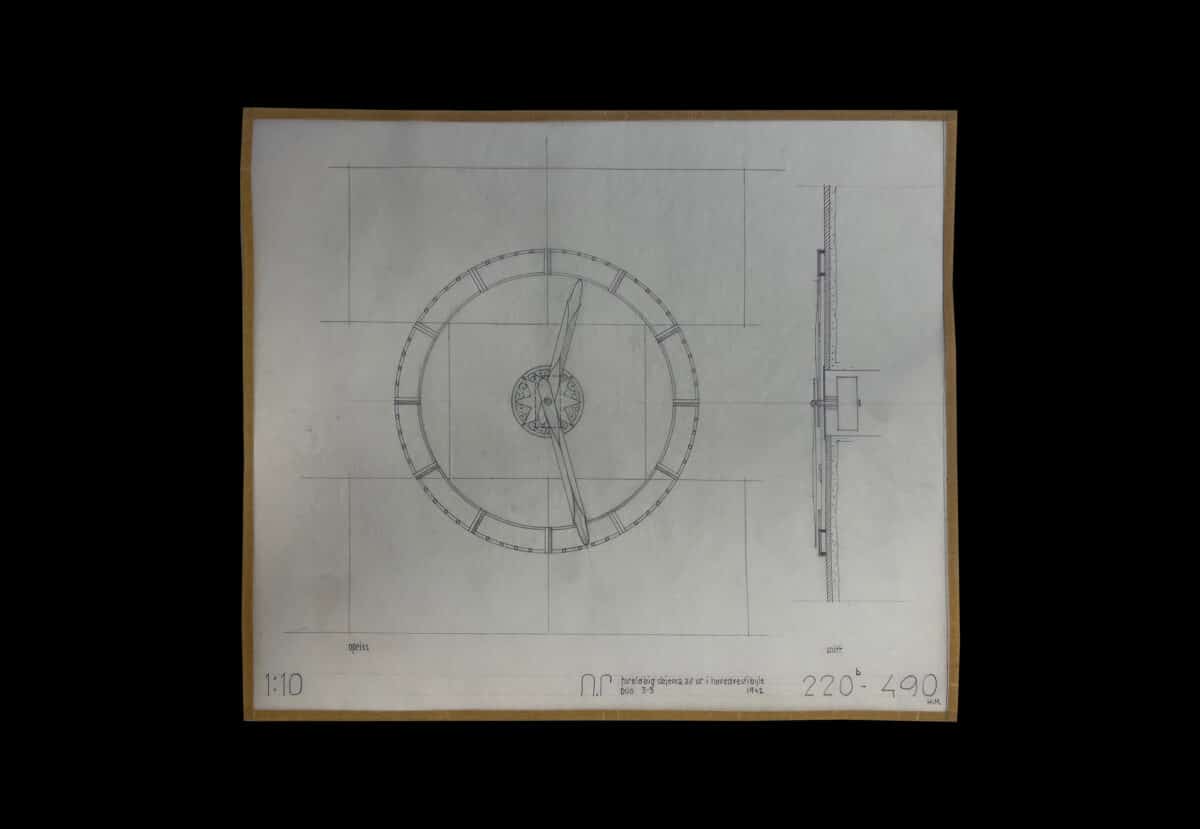

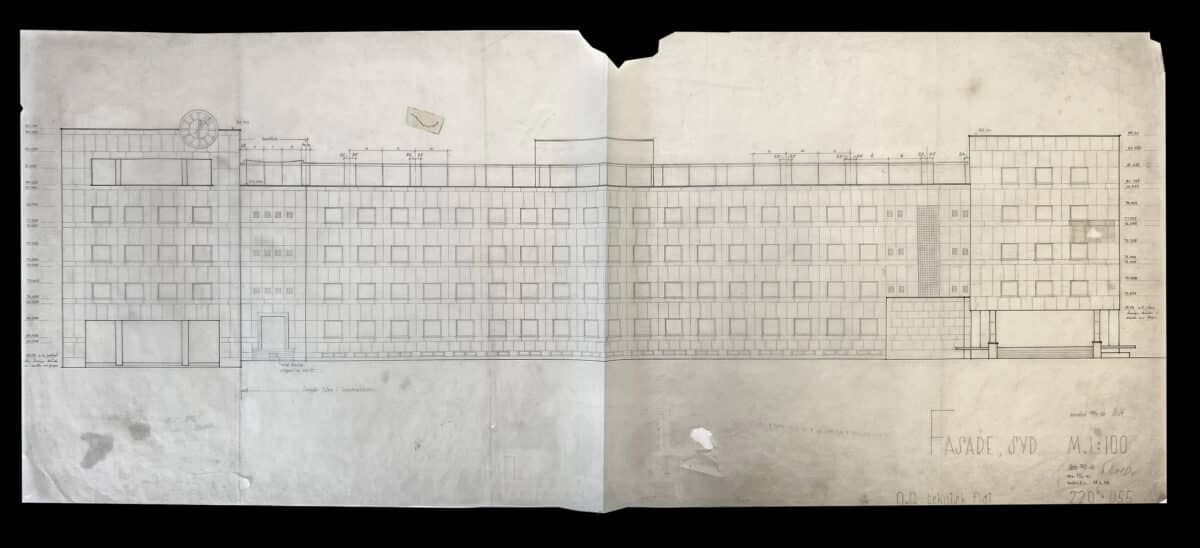

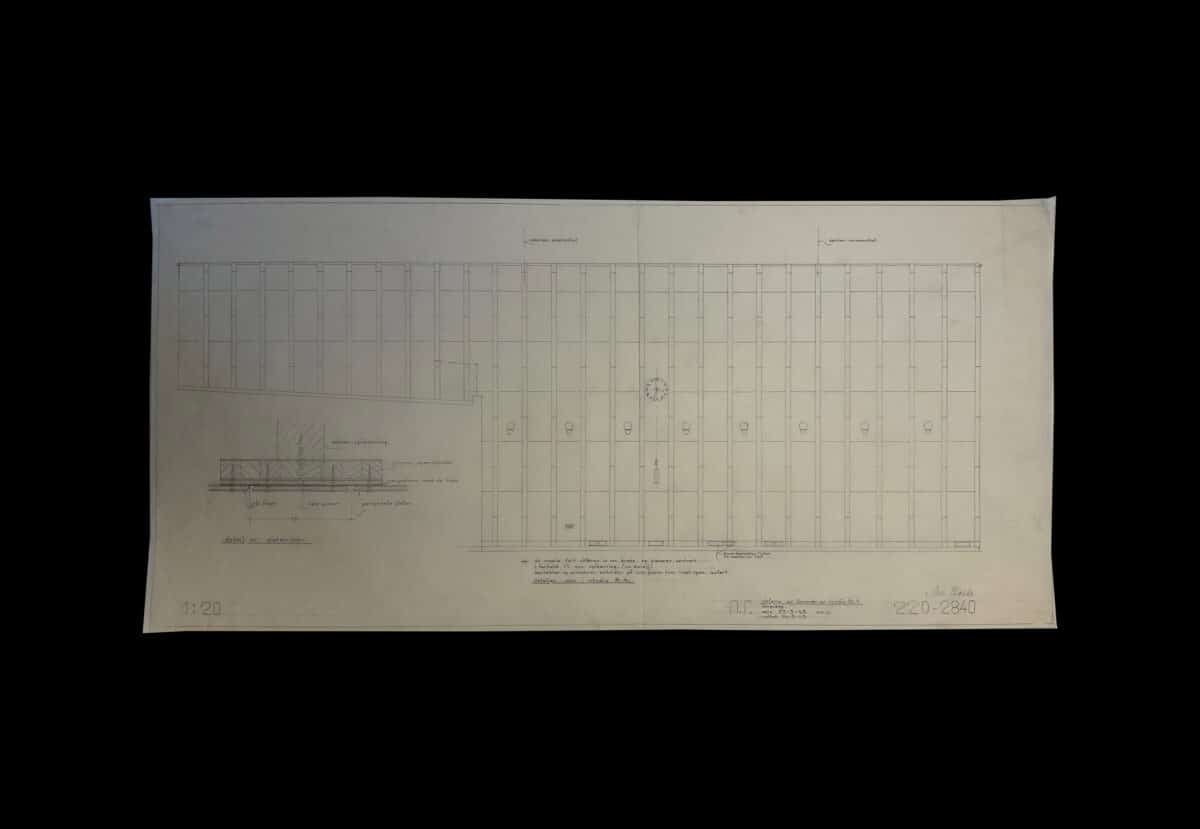

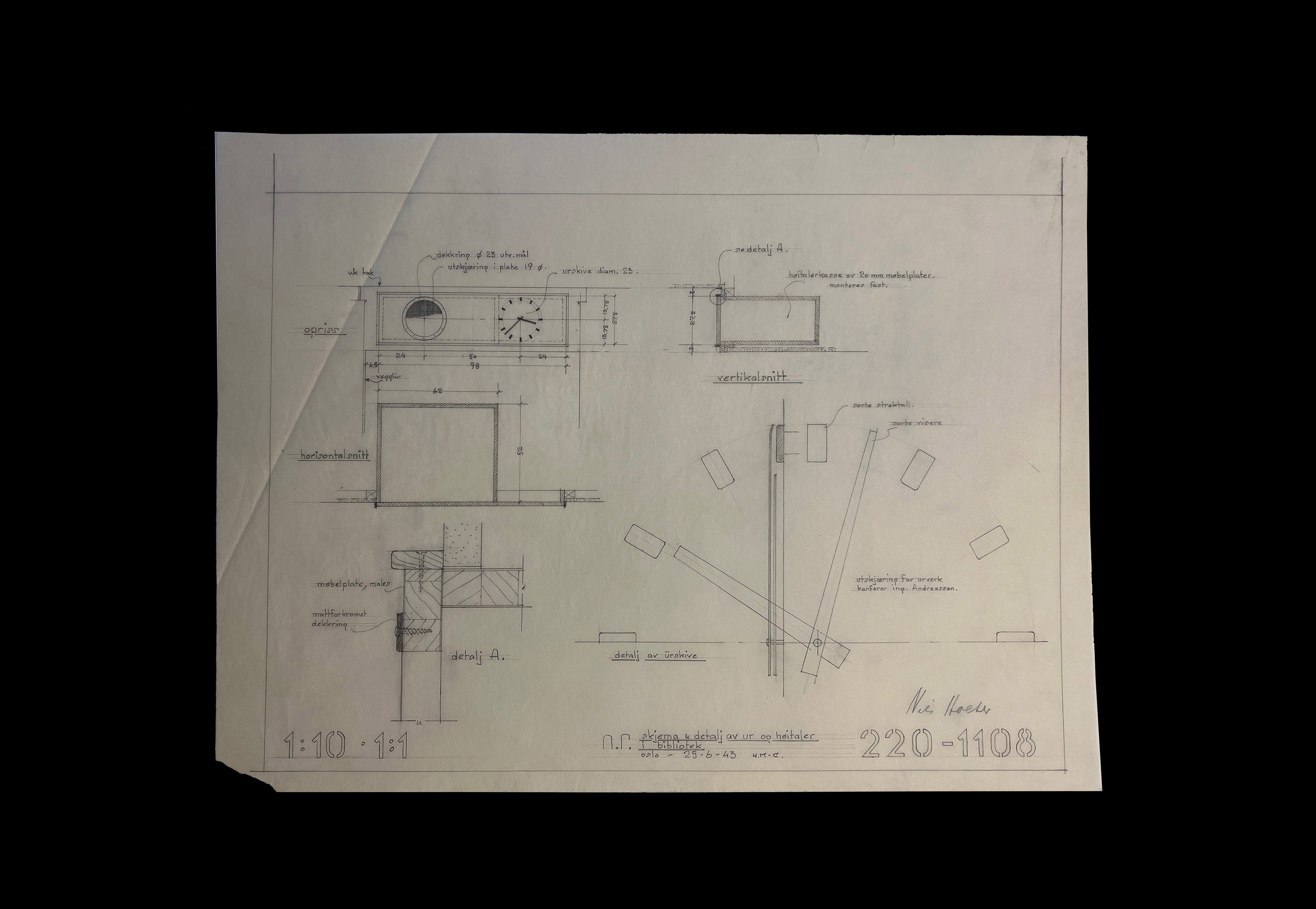

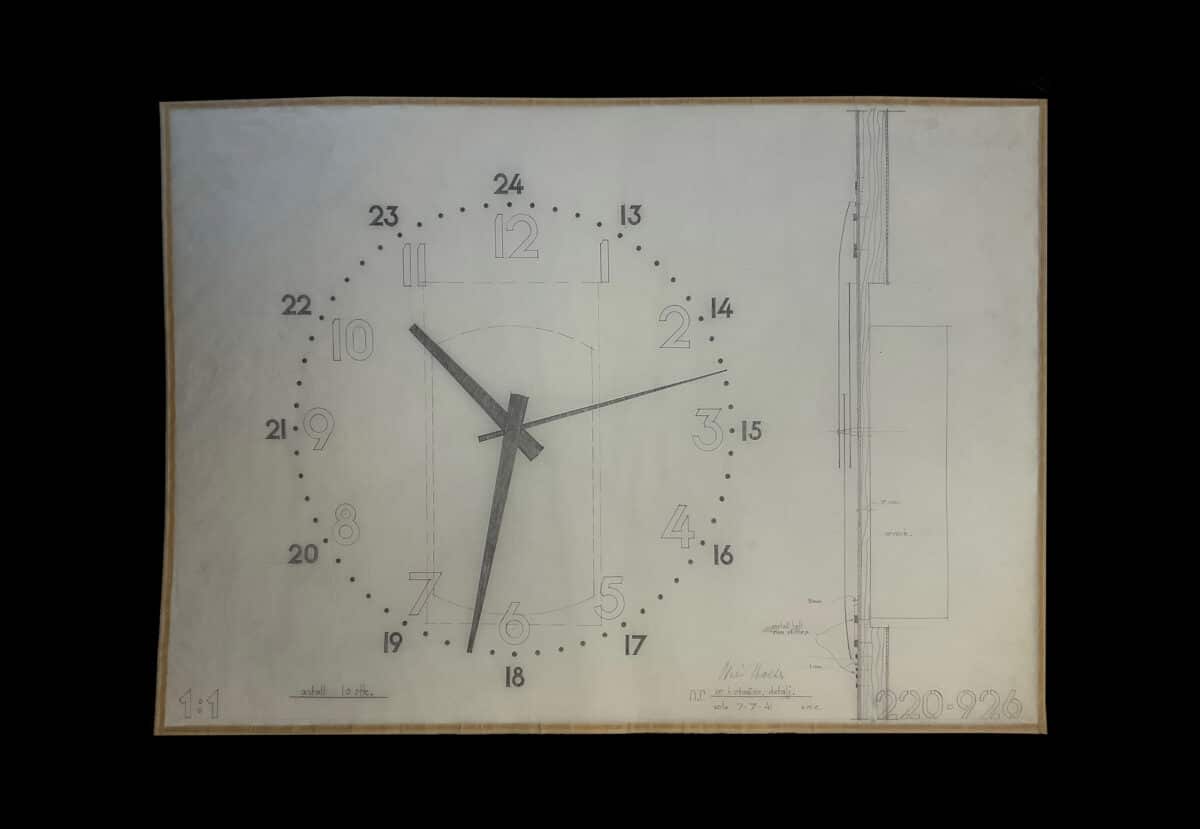

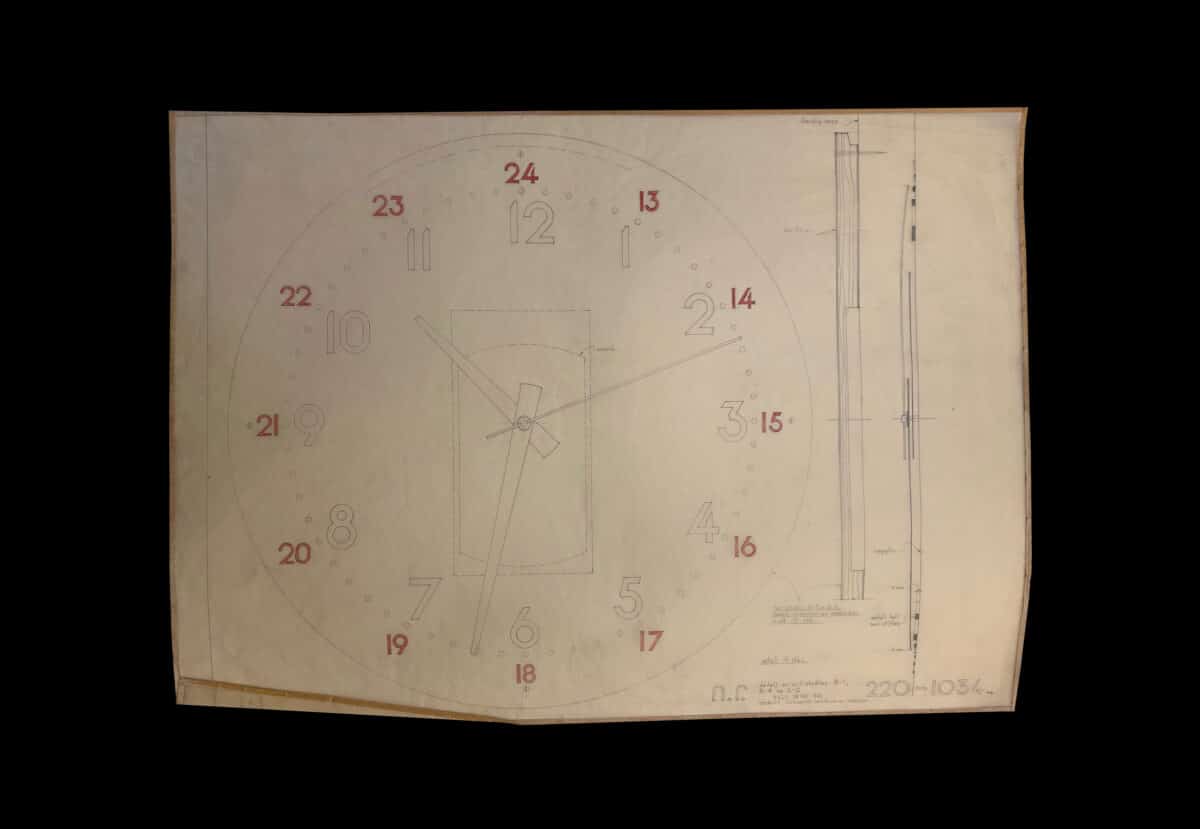

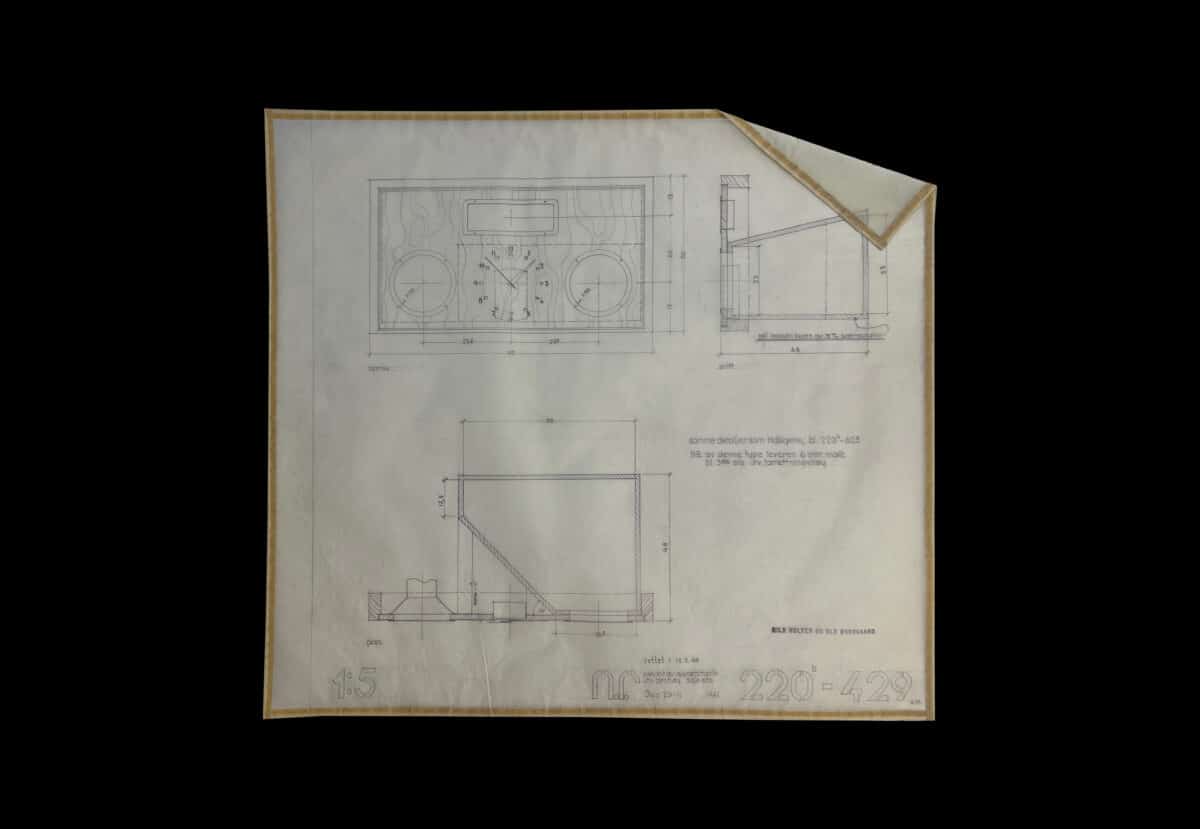

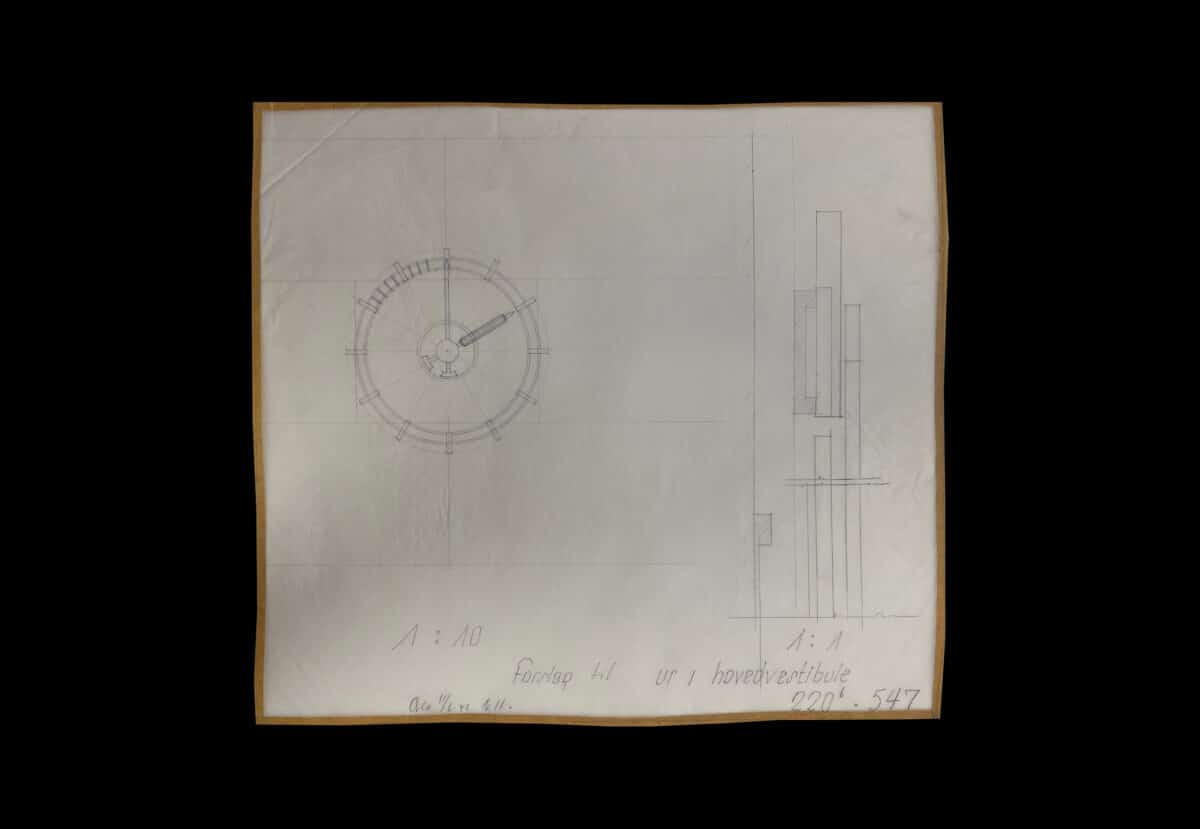

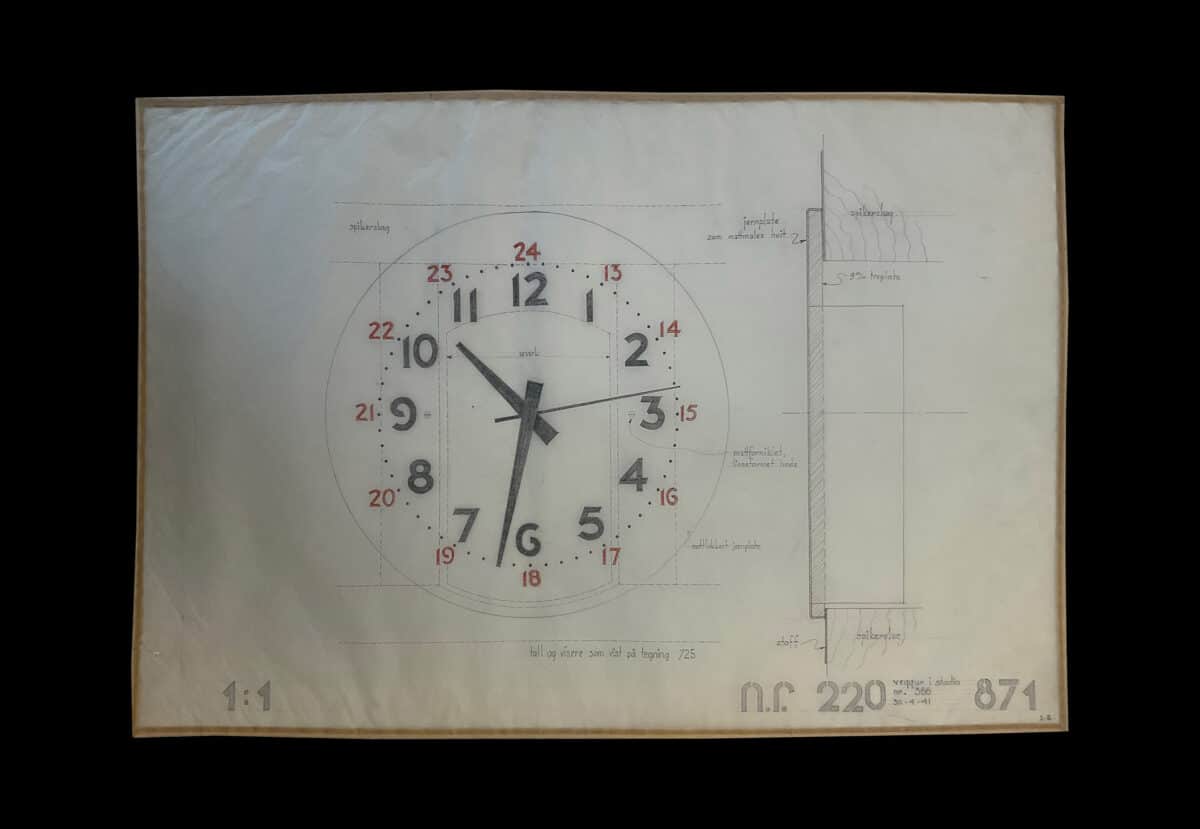

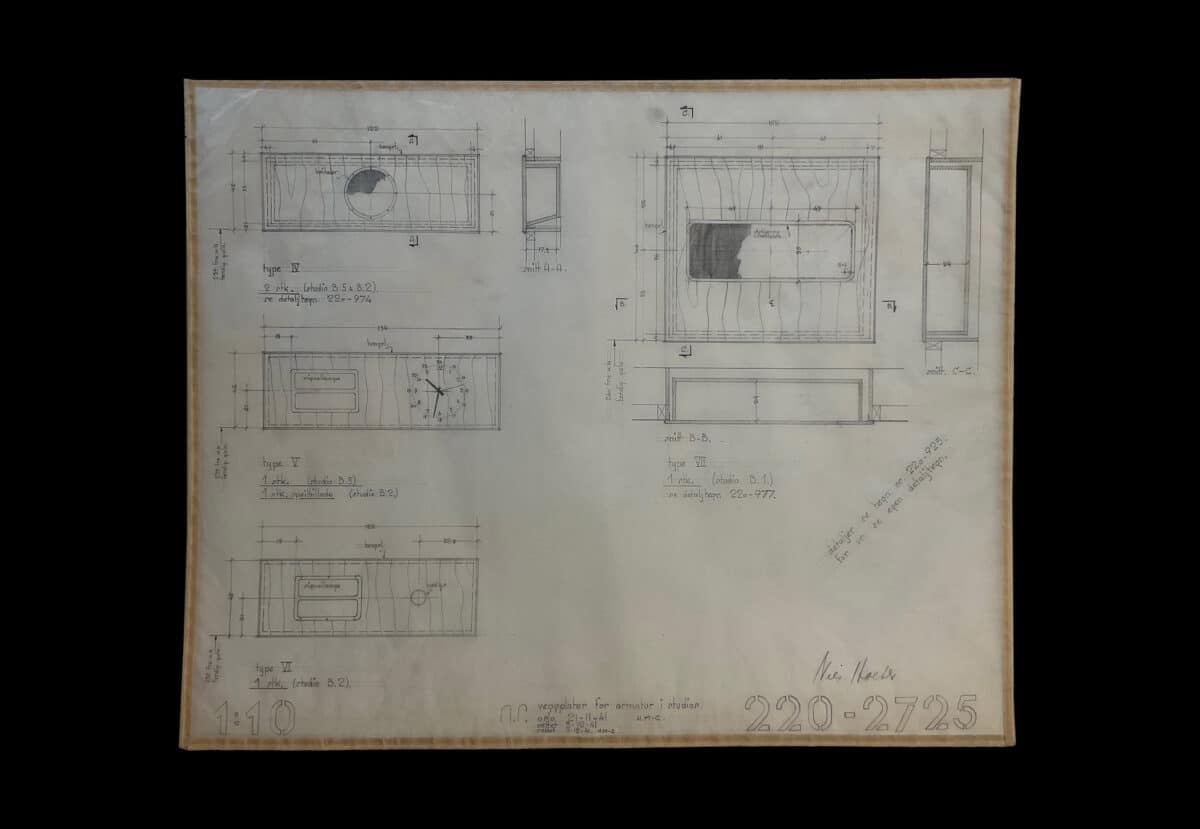

All drawings were done by Nils Holter Office during the NRK project period 1941-47, each made in pencil on paper with the initials of the draughtsman who drew it. Drawings from Nils Holter’s archives/Jan Bauck Arkitektkontor. Photographs courtesy of Jørgen Johan Tandberg.

In the summer of 2024, and after several failed attempts, I was granted access to the archives by the late Nils Holter, the modernist architect behind the NRK broadcasting building in Oslo. The building was erected between 1938 and 1950, following a 1935 competition; it was at the time a completely new and radical building typology in Europe, and given the novelty of broadcasting technology, Holter’s task was really to plan for the unforeseen demands of the new media and its spatial requirements. With the explosive growth of modern media, it was then extended and transformed for nearly eight decades, all according to the rapidly changing technology for radio broadcasting. Finally deemed obsolete and sold to a real estate developer in 2020, the exact fate of this national monument is now uncertain. The drawing archives have been in the private ownership of several generations of Holter’s younger associates and were largely left untouched in their original drawers since the 1940s. A particularly fascinating discovery was the numerous drawings of beautiful clocks for studios, meeting rooms and common areas, which seem to have been a major preoccupation within Holter’s practice. Designed before, during and after the German occupation of 1940–45, they are a testament to a particular period in Norwegian design history, but also to the role of telecommunications and radio in our understanding of time, and to the development of a national standardised time.

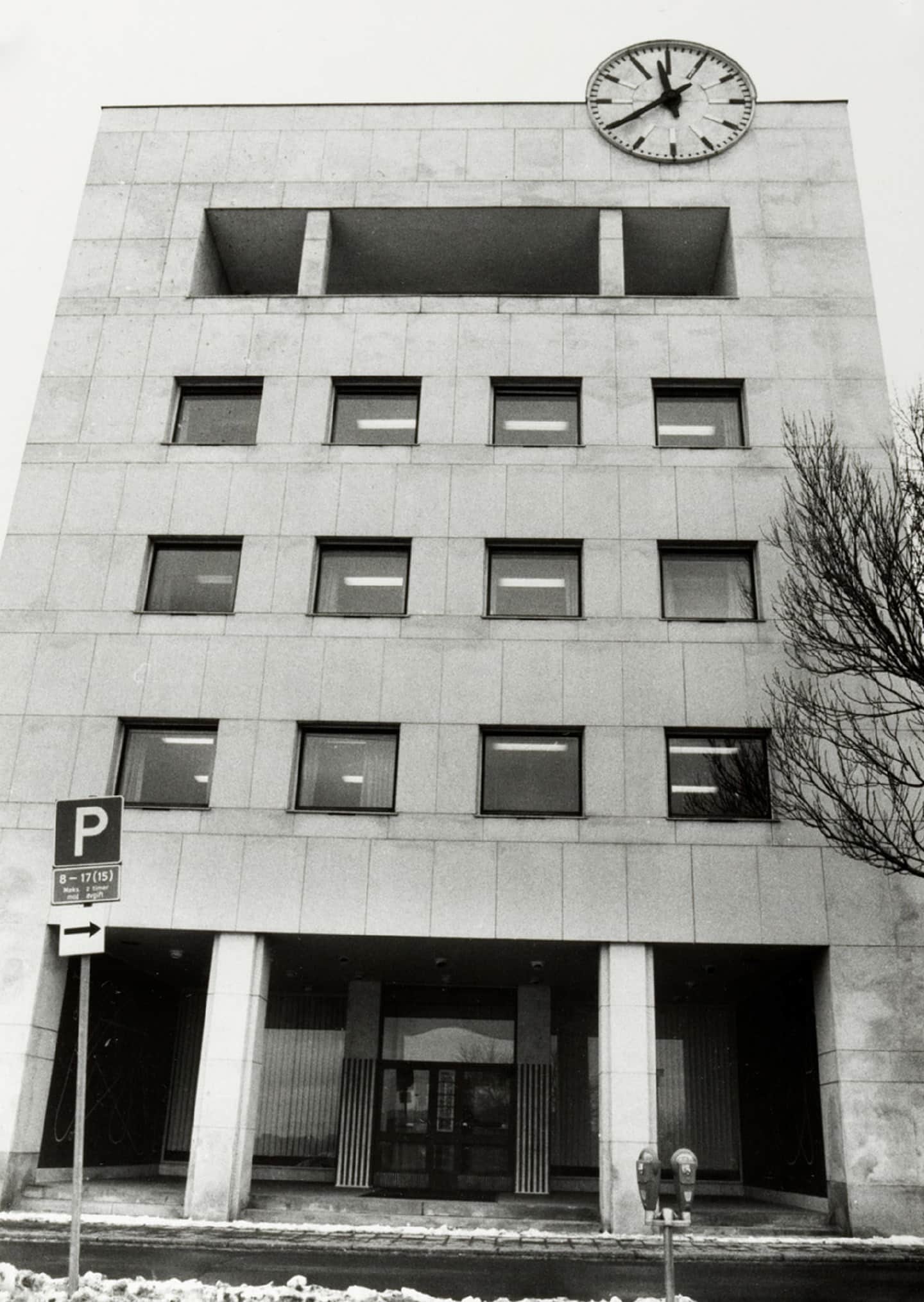

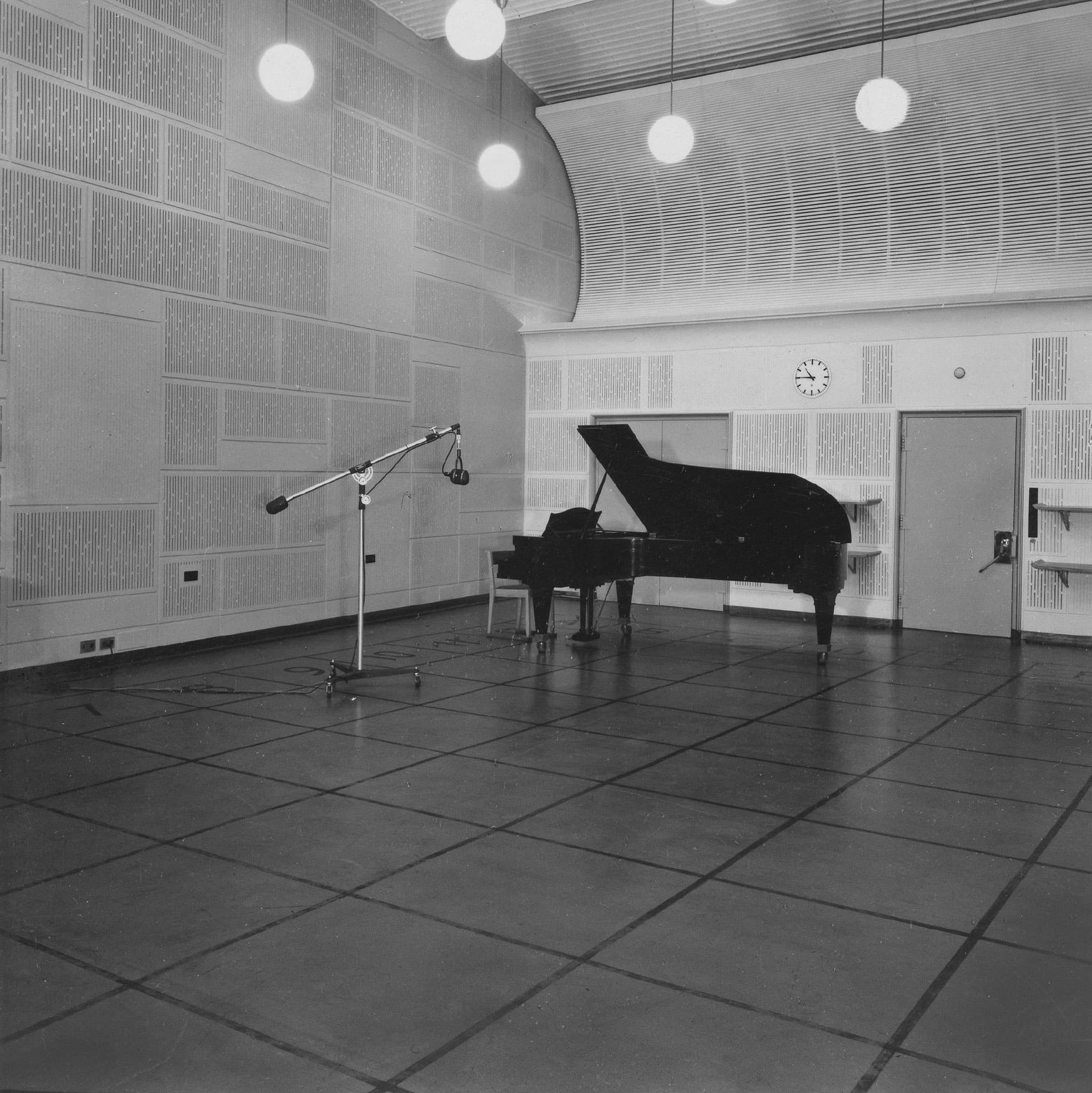

Most visitors to the NRK broadcasting building in Oslo in the late 1940s would approach from the east, by Suhms gate by way of Kirkeveien. Their first glimpse of the building itself would be the large clock on the south-eastern corner of its oldest wing, with dark metal hands, hours and minutes mounted directly onto the pale granite façade. Currently, it is only this corner with the clock that can be glimpsed from Kirkeveien, between foliage of the large trees planted on the site in the 1950s, now nearly as tall as the building itself—and in the fall of 2024 through scaffolding. Yet the surrounding area was less developed in the 1940s, and the entire eastern façade of the broadcasting building could most likely be seen from hundreds of meters away, both from the east and from the south. Arriving at the building’s main visitors’ entrance, another equally large clock could then be perceived perched at the top of the technical wing B, at the short south-eastern façade. This wing had been ordered, designed and built during the German occupation, and together with the extension of the middle wing, it changed the main orientation of the building to face Suhms gate, creating the necessity for a new clock in this direction. Passing through the front doors to the vestibule, an earlier clock, originally designed in 1941, backlit and mounted on curved, polished stucco, overlooks the interior of the reception area, slanted downwards from over the glass doors to the performers’ corridor to face visitors directly. From here on, clocks, as bespoke and delicately designed parts of the interior, are nearly always within sight throughout the old building, carefully integrated into the walls of corridors, studios, control rooms, offices and meeting rooms.

The façade clocks of the broadcasting building had a symbolic effect, placing it in the company of major public buildings such as the Oslo cathedral (as transformed in 1850), the central train station Østbanehallen (1882) and the city hall (1931–50). Yet the great number of visible clocks in the old broadcasting building also reveal the urgency of their practical purpose, in an era before clocks were set automatically through satellites. The comparison to early train stations is particularly relevant: in the same way that passengers arriving at the stations were reliant on keeping the same time as their train’s conductor in order not to miss a departure, the many clocks of NRK at Marienlyst subjected employees and visiting performers to a single, standardized time in order not to delay broadcasts. Lewis Mumford writes that ‘The clock, not the steam engine, is the key-machine of the modern industrial age’.[1] But there is another relation between the new and efficient means of transportation, and the invention of wireless communication: their effect on the perception of time, and the development of standardized time.

Together with the many lamps that signalled passers-by to silence by notifying them that a radio transmission was scheduled, the clocks’ omnipresence within the broadcasting building reveals the medium of radio as a child of modern standardisation and planning processes, and they indicated an ambition on behalf of the early corporation to be shaped by efficient, contemporary organisation methods. And where the traditional façade clock of a public building acted as a reminder of institutionalised power, symbolically claiming ownership of a shared temporality, this was an effect that at NRK would become magnified by the thousands. The sociologist John B. Thompson argues for the importance of ‘despatialized simultaneity’ as an effect of the new electronic media.[2] The concept of time had previously been tied to that of distance, or how long it would take for a message to travel from one place to another. As messages could be transmitted and received nearly instantaneously, ‘the experience of simultaneity was detached from the spatial condition of common locality’.[3] This, in turn, led to the invention of standard time: it was no longer possible for any area to operate with their own, local time when connected to major transregional or international communication projects. Presented orally to the nation through radio, and later visually through TV broadcasts, the NRK’s audiences were consistently reminded of an official and standardised time, a reliable and shared temporality broadcast on an increasingly regular basis. Rules for standardised time had existed in Norway since 1895, but until the arrival of the new media of radio and television, there were relatively few points of contact between this standardised time and the population. The Marienlyst clocks were in this way really where the time of the broadcasting corporation started becoming the acknowledged national time, at least to the public. Later, as NRK began regular television broadcasts from 1960, an NRK clock would soon grace the TV screens across the country in between airings. ‘Setting the time according to NRK’ is a well-known expression that has survived from the pre-satellite era of early radio and television.

Clocks grace the façades of several of the early broadcasting buildings, but far from all: there were clocks at the Norddeutsche Rundfunk in Hamburg (1931), the BBC Broadcasting Building in London (1932) and the Maison de la Radio in Brussels (1938), but not on the buildings that had become particularly important references to Holter and the NRK engineers, such as the Haus des Rundfunks in Berlin (1931), the Funkhaus in Vienna (1939) and Radiohuset in Copenhagen (1945). There are also no façade clocks on any of the awarded proposals in the competition to design the Norwegian broadcasting building in 1935, including Holter’s winning entry. Tracing the location and time of occurrence of the clocks on the Norwegian broadcasting building as they appear in drawings is therefore revealing certain key historical moments in the building’s history. For example, the original façade clock is absent from the initial planning application of 1938, and it first appears as a careful pencil sketch in the early façade drawings from 1938/39, otherwise drawn in ink. It becomes more prominent in later drawings, then moved to an extension which was ordered by the new leadership in 1941, during the German occupation (as the granite facades of the broadcasting building were not mounted until 1943, no earlier design of the clock could yet have been installed on the building when the extension was constructed). Behind the clock as installed, this new front of the building featured a windowless stair between floors of the executive offices to allow for secret meetings between members of the Nazi leadership. The clock is therefore located in an area of the façade without windows, increasing its iconic effect while also softening an otherwise tough, and very prominent corner of the building.

The second building phase, designed in the first years of the German occupation, changed the layout and composition of the broadcasting building drastically, giving it a new front façade. Where the first building phase had only a very short façade for the main entrance, on the short end of the original wing A, the extended middle wing M, facing Suhms gate, now became the building’s face towards visitors. In a 1941 planning application this façade featured a large clock placed above a new entrance to the M-wing (May 30, 1941). This was where Holter had planned the vestibule for another large studio open to the public; this studio was not built, although the vestibule was, and so the clock was never installed in the location indicated by the application drawings, but is instead moved to its final, and more prominent position at the top front of the new technical wing B in drawings dated later that year. Rising partially over the façade, it became visible also to visitors approaching the building from the west. In photos from May 1943, it has still not been installed, and its absence testifies to a decline in building activity at Marienlyst that followed the Nazis’ initial ‘optimism’ in the occupation’s first period from 1940. The clock was in the end only detailed and built in 1946, when the ‘free NRK’ which had been based in London was re-joined with the occupied NRK at Marienlyst.[4] It is one of a series of alterations and improvements made in the immediate post-war period, to remedy the sudden drop in both construction endeavours and building maintenance that followed the German declaration of ‘total war’, where all productive facilities were re-organized towards more direct warfare-purposes.[5] Arguably the clock, as installed after the occupation ended, also brings some attention away from the symmetry of the façade towards Suhms gate.

Clockworks (‘uranlegg’) for the interior of the broadcasting building were delivered by local engineer A. H. Andreassen, and as often before, German broadcasting buildings gave the Norwegian broadcasting corporation a standard for comparison also before the occupation.[6] The national architect Hans Fredrik Crawfurd-Jensen in 1940 confirms that the equipment to be delivered by Andreassen was the same used in the various German broadcasting buildings, manufactured by the firm ‘Telefonbau und Normalzeit G.m.b.H’ which Andreassen represented in Norway, and which was state of the art at the time.[7] Andreassen first delivered his tender to deliver clocks for the broadcasting building in 1938, but the commission was delayed until January 1941, also at the recommendation of the national architect, based on an expectation that the technology would be more efficient by the time the building works had progressed far enough for the clocks to be installed.[8] Within the broadcasting building, a ‘main clock’ (sometimes referred to as the ‘mother clock’) was to be installed in an amplifier room on the first floor. In addition to being connected to the series of clocks throughout the building (a total of 80 clocks was forecast to be installed), it was to emit a sound that could be used to broadcast to other transmitters across the country for them to synchronise to a nationwide NRK time. 33 other clocks for the interiors are specified within the original contract, to be installed by January 1st 1941, and with an option for 29 more clocks at a set price, to be delivered later. The tender requested that all the clocks, located mainly in studios, corridors and control rooms, but also in the executive offices, were to be ‘barely audible at a distance of one meter’, in order not to disturb the sound of the radio programs themselves.[9] The Oslo watchmaker Alf Lie (1887–1974), trained in Germany and the USA, had overseen the upkeep of NRKs clocks in their previous locations, and he would again be solicited to deliver services to NRK in the new building. The collaboration with Lie reveals the rudimentary state of the technology in this period. From his watchmaker’s shop in Oslo, Lie would keep another ‘main clock’, from which he would regularly transmit the time to Marienlyst through a special phone line, the installation of which was commissioned by the Nazi technical director Fritz Gythfeldt directly and paid for by the broadcasting corporation. The firm of Andreassen, delivering the clocks, would then keep all the NRK clocks synchronized with the signals sent by Lie to Marienlyst. Delivering the nation’s shared time was in this way done through German mechanics but run according to Lie’s small shop in Prinsens gate 22 in central Oslo.[10]

In the architects’ drawings, the clocks stand out as a repeated compositional motif: their circular shapes in the room elevation drawings mirror the spiral staircases of the plans, the circular integrated speakers, and the spherical hanging lamps of the interior sections. Four different sets of initials appear on the drawings of clocks for the broadcasting building coming out of Holter’s office, apart from Holter’s own (N.H.): D.B., H.M.C., H.M. and J.F., and as with other interior details and fittings, the clock designs appear to have been the subject of a great amount of working hours charged by the practice to the corporation, in the period of the German occupation especially. They were very far from todays’ notion of mass-produced and off-the-shelf objects: most of the clocks were repeatedly re-drawn at a scale of 1:1 and were completely integrated parts of the interiors. Rather than repeating a single design across the building, the architects created variations and explored options for the clocks in each of the rooms and studios. In addition to a variation in clock sizes and colouring, whether the hours on the clocks were numbered or not varied, as did whether the numbering showed 12-hour time, or both 12-hour time and 24-hour time. Some hours were marked by dots and some by strips, with or without rounded corners. Some clocks were without a casing, integrated into the boards mounted on the studio walls, only hands and hours showing, others had a matte-painted metal watch face that gave them a visual contrast to the rest of the interior. In some of the studios, such as studio C2–3, the clocks were installed as parts of larger technical devices, ‘speaker boards’ or ‘instrument boards’, containing both a clock, a speaker and a signal lamp, all mounted together. Although the architects experimented with curves and geometric ornamentation on the clock hands and faces, all clocks installed in the broadcasting building were ultimately very minimal in their designs, with sans-serif lettering.

Rumour was that the thousands of architects’ working hours billed to the German occupying government in the design of these elaborate details were really a form of ‘filibustering’ to delay construction work: in effect killing time by drawing clocks. What is certain is that the architect had to navigate within the intricate power plays that plagued the corporation—between German Nazis, members of the Norwegian fascist party, and employees loyal to the government exiled in London—and unsure whether the building would in the end belong to the third Reich or to a liberated NRK. With most of the original broadcasting studios now demolished or transformed over time—often by Holter’s own practice—nearly all the clocks are also lost. Apart from the large clock in the main reception, the two backlit clocks of the vestibule of the large music studio are upon inspection perhaps the most lavish of those remaining today: they were designed in 1947, with the new investments in the building after the occupation ended, and they consist of opal glass watch faces that were sandblasted at the rear, surrounded by polished steel trims, and mounted onto full height mirrors placed symmetrically in the room. The hours are not marked with lettering, only as strips in white to the rear of the glass clock face, arms slender, in black steel.

- Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1934), 14.

- John Thompson, The Media and Modernity. A Social Theory of the Media (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995), 32–33.

- Ibid.

- Drawing 220b – 838. September 9, 1936 – October 30, 1936. Holter’s archive.

- Joshua Hagen, Robert C. Ostergren, Building Nazi Germany. Place, Space, Architecture, Ideology (Lanham: 2020, Rowman & Littlefield).

- Architect Johan Noodt at Holter’s office, who had previously worked with both Blakstad & Munthe Kaas and Finn Bryn, was at this time responsible for the correspondence with Andreassen.

- The company had delivered to broadcasting facilities in Stuttgart, Berlin, Königsberg, Breslau, Frankfurt, Freiburg, Cologne, Munich, Nurenberg, Bayreuth, Karlsruhe, Dresden, Leipzig. The commission of Andreassen came recommended by Crawfurd-Jensen, as Andreassen had delivered clocks for the telegraph building in Lillehammer for which the national architect had also been in charge. Letter from A. H. Andreassen to Riksarkitekten. February 7, 1937. NRK archives. Letter to the building committee from Fr. Crawfurd-Jensen. October 4, 1940. NRK archives.

- Letter from Fr. Crawfurd-Jensen to Holter and Overgaard, February 2, 1948. NRK archives.

- Letter from A. H. Andreassen to Riksarkitekten, February 7, 1937. NRK archives.

- Originally, Astrofysisk Institutt at the University of Oslo was to deliver the time, but this arrangement appears to have changed during the war.

- Letter from A. H. Andreassen to Riksarkitekten, February 7, 1937. NRK archives.

- Originally, Astrofysisk Institutt at the University of Oslo was to deliver the time, but this arrangement appears to have changed during the war. Img_1736.

Jørgen J. Tandberg is an associate professor at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design. His PhD thesis explores the architecture of the Norwegian broadcasting corporation in Oslo, as the built infrastructure of an early technological mass medium. It is part of the ongoing research project ‘Provenance Projected: Architecture Past and Future in the Era of Circularity’.