Drawing the Curtain: Entangling rendering and theatrical space

Pliny the Elder recounted the following story in Naturalis Historia:

The two great painters of classical Greece, Zeuxis and Parrhasius staged a contest to determine the greater painter. When Zeuxis unveiled his painting, the grapes he depicted appeared so real that a bird flew down to peck at them. When Zeuxis attempted to unveil Parrhasius’ painting he discovered the curtains themselves were painted, exclaiming, ‘I have deceived the birds but Parrhasius has deceived Zeuxis.’

A computer programmer once made the following observation to me:

You use your hand to draw like a machine. Your hand fails but the drawing succeeds. I use a machine to draw like a hand. The machine succeeds but the drawing fails.

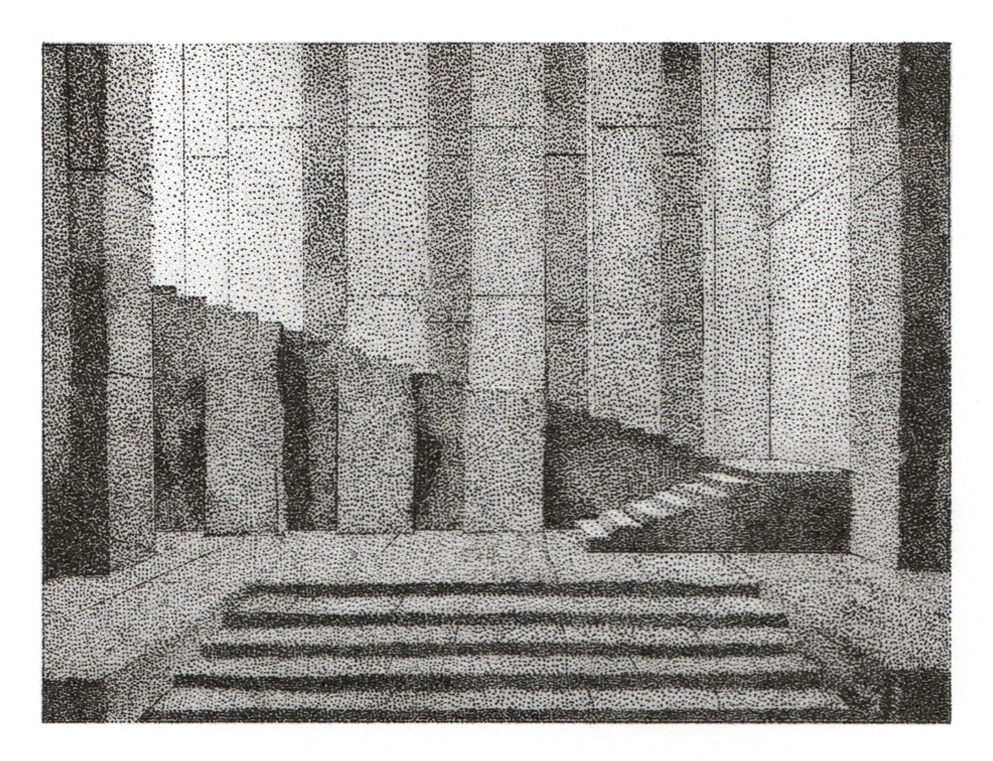

A pen and ink drawing on an inkjet print of a digital image that might be a scan or a photograph or a scanned photograph of a charcoal drawing depicting a space that was later built and photographed to look like the drawing that the drawing is of. Images have a way of complicating. Even before photography an 18th century student of architecture might have sketched the volute of a contemporary building that had been carved from a drawing taken from an engraving made from a sketch of a Renaissance example that was made from another drawing… ad infinitum.

Once something is remade – whether from an image or an object to become another image or an another object – shifts take place and a historical and material stratification builds layers that tend to lie beneath the face of thing we’re looking at, and so it complicates. Even to write these words I had to look at a drawing I made on paper as a digital image from a scan on a screen.

If you divide drawings simply into two categories: those that generate and those that remake (record, represent, reproduce), my drawings are concerned with remaking. I take an existing image – whether it’s a scan or photograph or digital rendering of a drawing, photograph, painting, figure, object, space – I convert it to greyscale and print a faint tonal base layer in CMYK with an opacity of about ten percent. Over the faint ghost print I make the drawing. The tiny stippled dots of the drawing bury the print whilst they extract the image. The final work is print and drawing that includes the subject image and its drawn representation. When scanned or photographed, the two strata of print and drawing become flattened into a single layer but both strata are still embedded into that new single image and so the image continues to complicate.

The particular image this essay is concerned with was first made with charcoal on paper by the Swiss scenographer Adolphe Appia in 1912. It was remade by me with inkjet print and ink pen on paper in 2015. Appia produced his drawing whilst developing ideas for a production of Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice at Hellerau. The frontal view (or parallel perspective) describes the setting for the scene when Orpheus descends into the underworld in search of Euridice.

Appia made his reputation by rejecting the long and tired tradition of European scenography that had been using single point linear perspective and its illusionistic capacity for creating depth with single enthusiasm since the Renaissance.

The basic structure of a traditional theatre (as well as its corresponding vocabulary) was inherited from Greece via Rome. The theatre (from theatron, meaning ‘place for viewing’) is divided into an auditorium, a dividing proscenium, and the stage or scenery (from skene meaning ‘stage’). The problem of this theatre structure is that the actors are on the stage and the audience are in the auditorium. The actors attempt to draw the audience into the fiction they are acting out, to pull their imagination out of their seats and into the suspended realm of disbelief of the stage. The threshold between those two spaces of the seat and the stage and the two separate realities they represent is embodied by the term, the ‘fourth wall’. It demarcates that invisible division between the two spaces and upholds the suspended disbelief. The modern rebellion of ‘breaking the fourth wall’ involves breaking down that illusion, to show the armature under the artifice.

To bypass these divisions (so the audience could cross the boundary with their imagination), Renaissance theatres used the visual lure of single point linear perspective to entice eyes so the mind followed (while the body stayed put in its seat). In theory the perspective (from Latin perspicere, ‘to see through’) helped the audience to see through the division so as not to see it at all. All three surviving Renaissance theatres – the Teatro Farnese (Parma), Teatro all’Antica (Sabionetta), and Teatro Olimpico (Vicenza) – used forced perspective to exaggerate ideal urban spaces described within a foreshortened stage. By forcing the perspective, the stage depth was visually exaggerated for audience members (while the actors walked around in a skewed nightmarish space). In effect, the theatres built out a three dimensional space according to the principles of a graphical device developed to produce the illusion of depth on the flat surface of a picture plane with the result that theatres became more like the drawings they were based on.

The orthogonal structure of single point perspective emanates from the point of the viewing eye where it reaches the rectangular picture plane before converging again towards a vanishing point in the pictorial distance. The basic failing of the Renaissance theatre is that single point linear perspective only works from a single point and breaks down when you stray from that point. In Renaissance theatres that money-spot was a single seat in the auditorium and the patron sat there. The further away you are from the patron’s seat, the more distorted your view becomes, progressively skewing into oblique angles that make no sense. The image fractures, the illusion dissolves.

By the early 20th century most sets had become simply illusionistic scenes in perspective painted on the back walls and side flats. Appia considered the effect to be flat and lifeless, that it left the audience stranded as passive spectators. His visionary turn was to introduce an architecture that made sense from all points of the stage and auditorium and to enliven this architecture with bold high-contrast lighting. Traditional theatres were lit by throwing light into the stage to illuminate the wall’s painted scenes. Appia instead devised a system to clad the whole theatre in white linen with thousands of lights behind it so that diffuse light could emanate from the space itself. In effect, the surfaces of the space became plastic light.

Just as plastic shading pushes and pulls the planes of a drawing, Appia’s mise-en-scène was defined through its tonal density that became a kind of three dimensional chiaroscuro, and so the stage perfectly reperformed his drawings. The density of the charcoal on paper became the density of light on set and when that scene was photographed, the grain of the black and white film capturing light re-enacted the granular blacks of the charcoal drawing. Ultimately then, the stippling of my drawing re-enacts the photographic grain and the dot matrix of the print that lies beneath. Through the 72dpi resolution of a screen (which is its own ‘fourth wall’) the images become virtually indistinguishable. The imagined space of the charcoal drawing and the built space of the photograph become one. The flattening space of the screen collapses material distinctions.

To make things more complicated still, digital drawing tools have now evolved to disguise themselves almost without detection. They can render the effects of lenses, they can render the lens itself, and with enough time and processing power, they can render all the atoms of its glass. It is the infinite resolution of impossible detail, though, that also reveals its artifice.

Architects were quick to make use of these digital rendering tools, tantalizing their clients with an image resembling a photograph of a finished building before any bricks had been laid. And so the temporal perspective is further dissolved, the strata are shuffled and shuffled again when the building is eventually realized according to the render and photographed from the same point of the render’s view. Photography will tend to re-enact the render because renders anticipate cameras, they produce spaces of pictorial hotspots, not unlike the patron’s seat in the Renaissance theatre, where the grand view emanates from the single point. Whilst pictorially-led, theatrical architectural spaces are nothing new – in Rome, for example, piazzas set up frontal views of church façades clad in fine stone with brick behind – these spaces are overtly theatrical in structure, their frontality is always readily apparent. The image-led spaces of the built render-world, however, are disguised. Their images hide themselves, coaxing us covertly towards their sequences of hotspots. Under cloak and dagger they make a stage of all the world, a space of endless images, all drawn like the curtains of a theatre.

Thomas Hutton is an artist and writer based in Bassano in Teverina.

This text was submitted in the long form category (1000-1500 words) of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2020.