Drawings as Cosmovisions

My decision to become an architect was triggered by my love of drawing. But during my university years in the 1990s, when digital techniques became widespread, nothing was more distant than the relationship between architecture and manual drawing. Without hand-drawn images, the connection between the body and ideas was gone, and so were the clues to how an architectural design was thought out. Only through the making of models did corporal exploration still have a place in architecture, but architectural models were considered expensive toys, slow to make, and below par in exactitude and digital reproducibility. Models help us understand many things, but it is almost impossible to start a project in three dimensions without first drawing it. Materializing a space requires drawing it in some way. The drafts of an architectural design are not only a letter of intent, but also an accumulative process of ideas and references that determine much of what can happen in future iterations. An architectural drawing is the place where imagination, the body, and memory all come together.

I recently found my very first drawings of an architectural space, done when I was seven years old, in an attempt to draw the office building where my father worked. The building had no facade, nor an external form, only the space I moved around in. In these maps, drawn during various visits, I recorded what happened in the spaces, such as the spot where I could find an unguarded packet of blank sheets of paper, or the number of steps needed to reach a distinctive window, helping me navigate through a maze of cubicles. In these drawings, stairs were events—the temperatures and sounds produced when stepping on different materials mattered. Colours were of utmost importance enabling me not only to find my way around but also to associate particular feelings with a space. This also applied to the furniture, which sometimes became allies, and other times were things not to return to. These drawings became a world of things, people and experiences. The office seemed like an endless universe, and the drawings allowed that universe to be mine.

Thanks to my lack of technical experience, I could insert in a single drawing the reading of the place in plan, with the measurements made by my steps, and simultaneously in section, when a staircase led to another world. I was even able to include through vague angles unmeasurable elements like farness, tiredness, and surprise. These drawings had no aesthetic value and were of no interest to anyone else, but like any drawing made by a child, they expressed many more things than we usually find in professional architectural drawings. When children make drawings of a space or place, they often represent a mix of things, people and experiences: i.e. the sun or rain, and distinctive elements like a ramp, a dome, or a waste bin. This rarely happens in professional drawings. We are well aware of the danger of visualizing architecture as images detached from their surroundings and indifferent to real activities and people.

The spontaneous sketches of my childhood had more to say than any architectural drawing I have produced in my thirty-year experience in professional practice: a corner where I could lie back unseen and someone saying hello were an integral part of the place. In those early drawings, there was no division between shapes and actions and every element in the drawing had something to convey. There was no architecture. Today, knowing that architecture must include more things than we normally consider, such as its relationship with the exterior, with resources, and with people, architectural representations seem not only insufficient but altogether wrong, because they separate constructions from the primary elements of subsistence. Against these partial views, we need to bring to light everything that architecture has concealed for years: its relationship with elements that have a bearing on our existence, such as water (hidden in pipes), waste (out of sight and therefore beyond our responsibility), the outdoors (denied), and the connection with others (those who come to mind and those who do not). For architecture to stop being an act of exclusion—and one of the most destructive industries on the planet—we need to imagine spaces that do not erase everything that happens within them.

In various courses I have taught at Yale, Princeton, and Harvard Universities focusing on private spaces in a shared world, I have asked my students to define their meaning of home. Their answers have ranged from specific spatial descriptions, such as ‘home is my bathroom, the only place where I can be alone’ or ‘home is my bed, where I work, eat, sleep, and interact with others’ and metaphorical narratives like ‘home is my mother’ or ‘home is my rent.’ In all cases, the students usually describe their homes as the place that defines them and explains their relationship with the world at large. I have always been struck by the fact that the reactions of young architects refer to interests that have little to do with what follows in their later professional journey. We make houses in one way and think of our own house in a different way. To surmount these contradictions, we have to stop regarding architecture as mere construction, and start acknowledging its immaterial aspects. In this way, memories and fantasies can have a place in it.

The contradiction between the variety of cosmovisions and the unidirectionality of monothematic representations is evident in the differences that exist between the two types of drawings conceived during the colonization of America in the late 16th century. The first consisted of plans of buildings designed in Spain to construct, from a distance, new gridded cities over lakes and mountains full of preexistences. The second offers a series of maps jointly drawn up by native scribes and colonizers seeking to make a new world legible. In the drawings sent to the colonies from Spain, buildings appeared on a blank slate, to be erected with no reference to the landscape or the culture. In contrast, the maps known as ‘Geographic Relation of New Spain’—commissioned by the Spanish Crown to explain the territorial organization and lifestyles of the conquered lands—show an overlap of interpretations where everything could be included. These drawings done in America were made by locals, in the tradition of Aztec, Maya, and Mixtec codices, and by Spanish officials who only understood European cartography methods. The maps of Zempoala and Teozacoalco (1580) combined Indigenous conceptions of space with the record of minerals, astronomic references, medical cures, and the temperament of the inhabitants. In these pictorial manuscripts, Catholic religious symbols coexisted with ancestral rituals and with different ways of counting years or describing the fertility of soils. Rivers, mountains, and vegetation were living entities that accompanied humans. In these maps, it is not rare to find birds and insects larger than cathedrals, and plants imbibed with a human spirit. The drawings are not only expressions of different ways of understanding the territory and its relations but are in themselves the creation of a new place that can fit in many worlds. They reflect the idea that being in the world is to ‘be with,’ not to ‘be in,’ and simultaneously create a new gaze and a new place. The drawings bring together various forms of existence, in combination with spatial compositions born out of personal narratives, words composed of the material and the symbolic, where there is no difference between customs and constructions, nor between bodies and the earth.

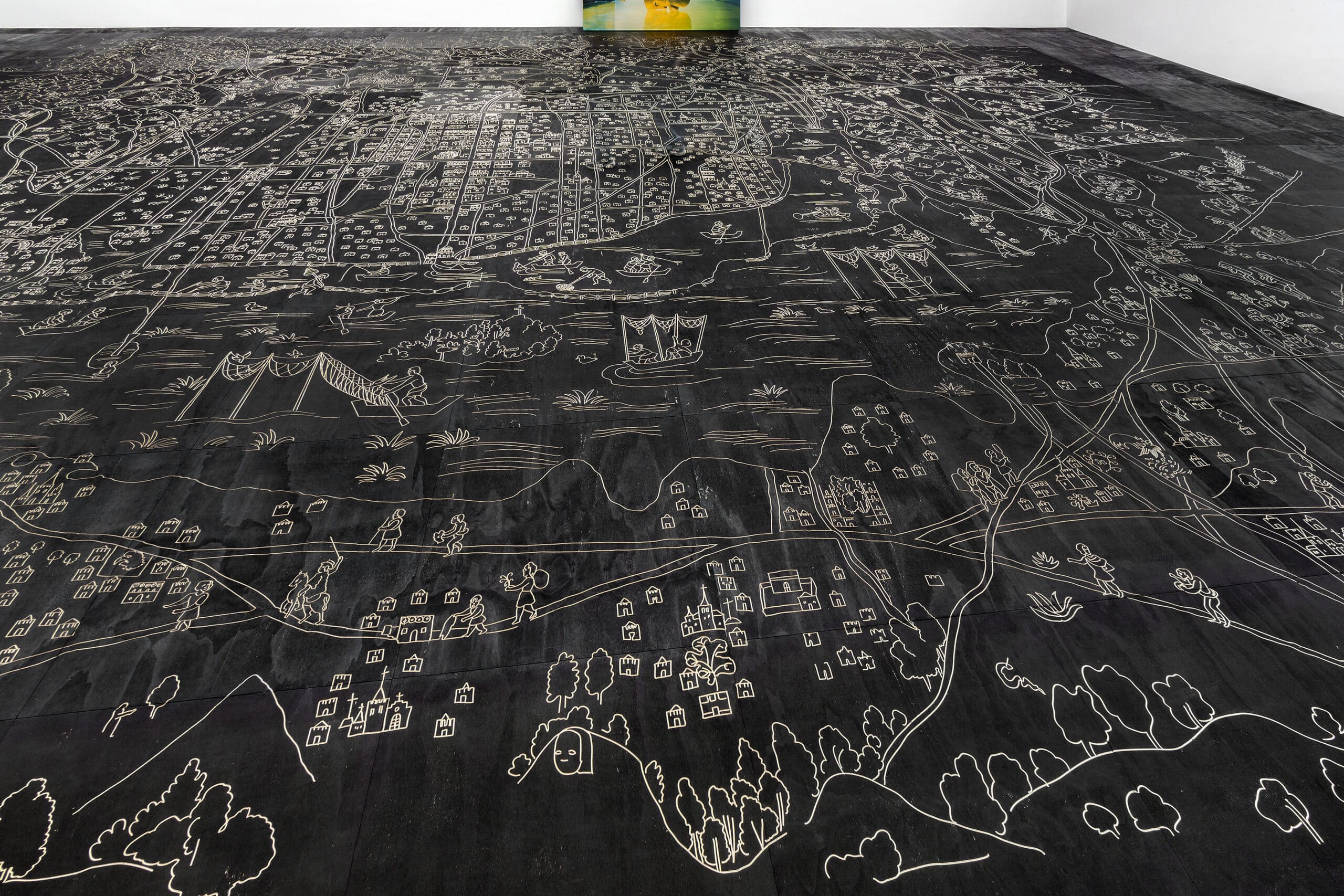

In recent years, the Mexican artist Mariana Castillo Deball has made a reinterpretation of these maps, engraving them on wood on a large scale on the floor of exhibition spaces, and adding not only layers of information through her gaze but also a corporal reading through the movements of visitors. In Vista de ojos (2014) and Finding Oneself Outside (2019), Castillo Deball highlights the rift between what Spanish cartographers wanted to represent by recording the territory to identify the rich resources and the dangers of colonized lands, and what indigenous scribes identified as territory: a portrait of the community, of its past and its beliefs. With the work of Castillo Deball, the recording of territory yields a new landscape to be treaded and read in different ways.

For drawings to have the power to take us to places that do not yet exist, we have to imagine them as living works, as layers of dissimilar interpretations, places where the forms of constructions are of the least importance. A series of paintings completed by the Argentinian artist León Ferrari from the 1980s to the early 2000s shows something very close to a world with no forms, such as an extended bed for everyone, with bathrooms, persons, trees, tables, spaces in which to be alone, and spaces for living together, without cars, and no hierarchies. His drawings Barrio, Ciudad, and Dos calles are labyrinths of cities—with no doors—that trigger thoughts on new ways of building without enclosing. Ferrari uses huge sheets of paper as if they were collective bedding. In his drawings, the world is an assemblage of dispersed objects, there are no distinctions between spaces for some and spaces for others, and though there are many beds, there is no rest. Spaces appear as a framework without social, gender and economic divisions. People are visible from above; through the far aerial reading akin to our contemporary view of the urban fabric, with inhabitants regarded as quantifiable figures, devoid of personality and feelings. I like to think that the absence of passion in Ferrari’s figures is a critique of our current society and spaces, not an exemplification of our essence. I prefer to consider that his drawings show not the type of places that define us but those which we want to escape from. What’s interesting about Ferrari’s maps is that one can enter and exit the spaces freely, with no boundaries: we find washbasins scattered all over the city, beds and chairs for everyone.

The first step towards achieving a world not divided into different spheres is to introduce our differences in the way we depict spaces, so that our needs and the multiplicity that we are and which surrounds us are present. Throughout history, architecture has been the shelter and the carpet of people in the world. But if the relationship between constructions, human behaviours, and dreams has no place in our drawings, how are we going to achieve a world of our own that is also a world for others? How can there be room for ‘the different’ if we keep using the same solutions, the same mute drawings? Improving the interaction between buildings, people and the environment implies expressing other things, and for others; addressing what we still systematically omit in our professional drawings, and by extension in our cities. To create communities, do we only need beds entrapped in tiny cubicles, but with unlimited use of the Internet and shops disguised as public space? We need drawings that no longer disguise the distinctions between the oppressed and the oppressor, the improvised realities and the fixed constructions, and the individual desires and the collective needs. We need architecture as a way to think, drawings as a way to find, and buildings as a system to connect and no longer divide.

Fernanda Canales holds a PhD in Architecture from the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid, an MA from the Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña in Barcelona and a BA from Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City. Fernanda is the author of the books Shared Structures, Private Space (Actar), Architecture in Mexico 1900-2010 (Arquine), Mi casa, tu ciudad (Puente Editores) and Vivienda Colectiva en México (GG), and has published essays in AA Files, El Croquis, The Architectural Review and Perspecta, among others. She has taught design studios at the Politecnico di Milano, GSD Harvard University, Princeton and Yale School of Architecture.