Hans Hollein: Infinite Space

Between 1959 and 1964, the sculptor and designer Walter Pichler (1936–2012) and the architect Hans Hollein (1934–2014), working in dialogue, introduced a radically adventurous new plasticity to form, questioning the functional idea of architecture as shelter and its symbolic role as monument, as well as calling for the architect to work as a freely creative mind. As they put it in a 1962 manifesto responding to the circumstances of the space and media age:

Today, for the first time in human history, … when an immensely advanced science and perfected technology offer us all possible means, we build what and how we will, we make an architecture that is not determined by technology but utilises technology, a pure, absolute architecture. Today man is master over infinite space.

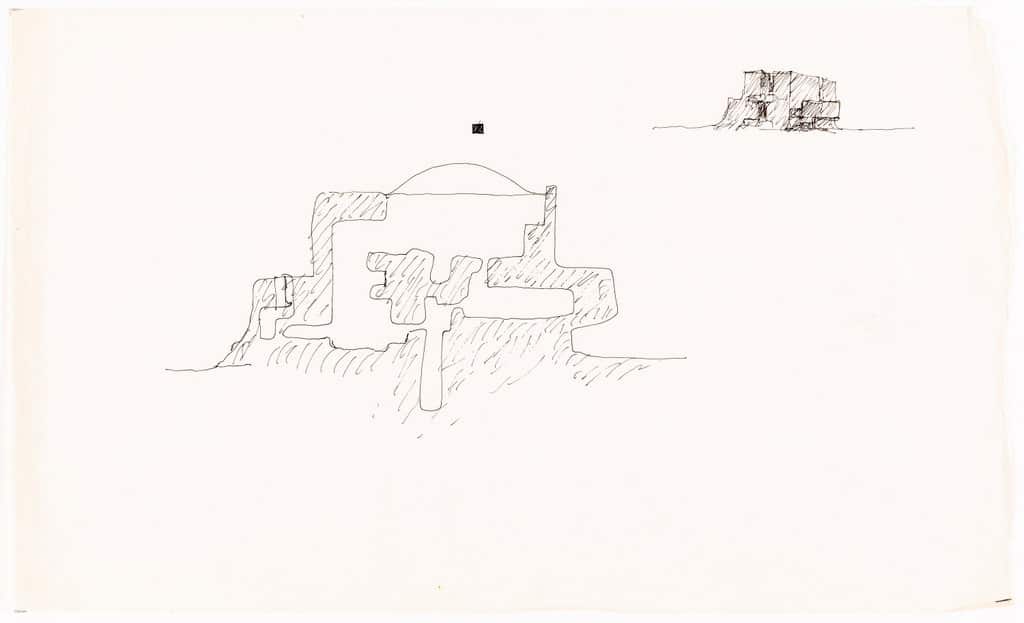

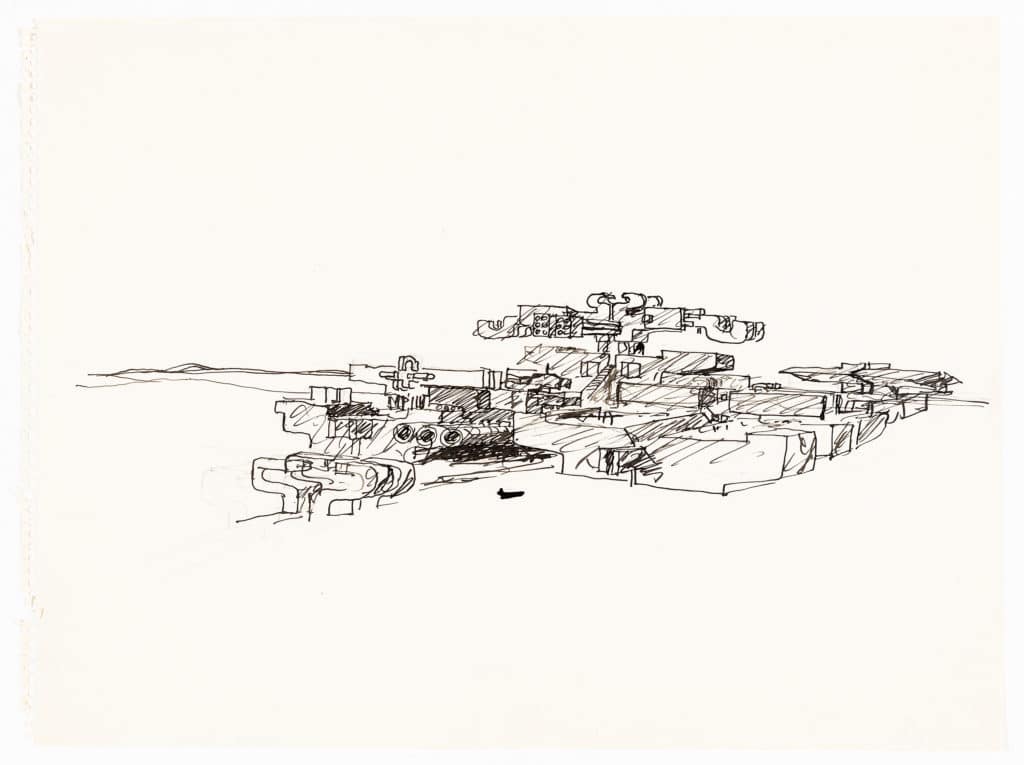

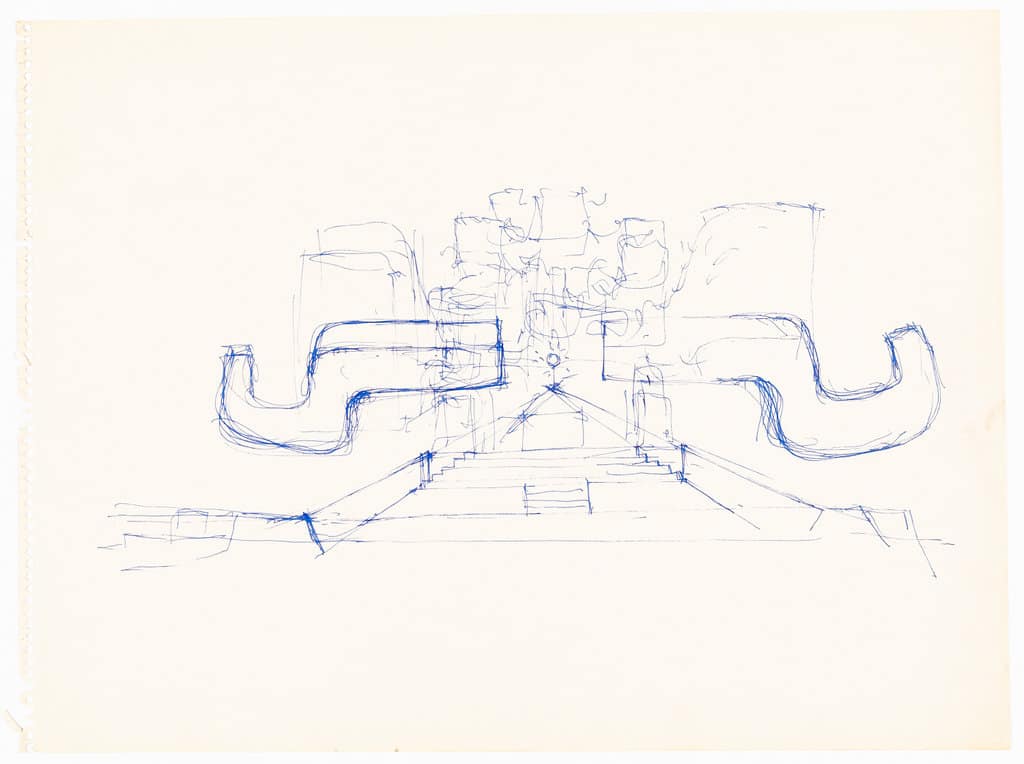

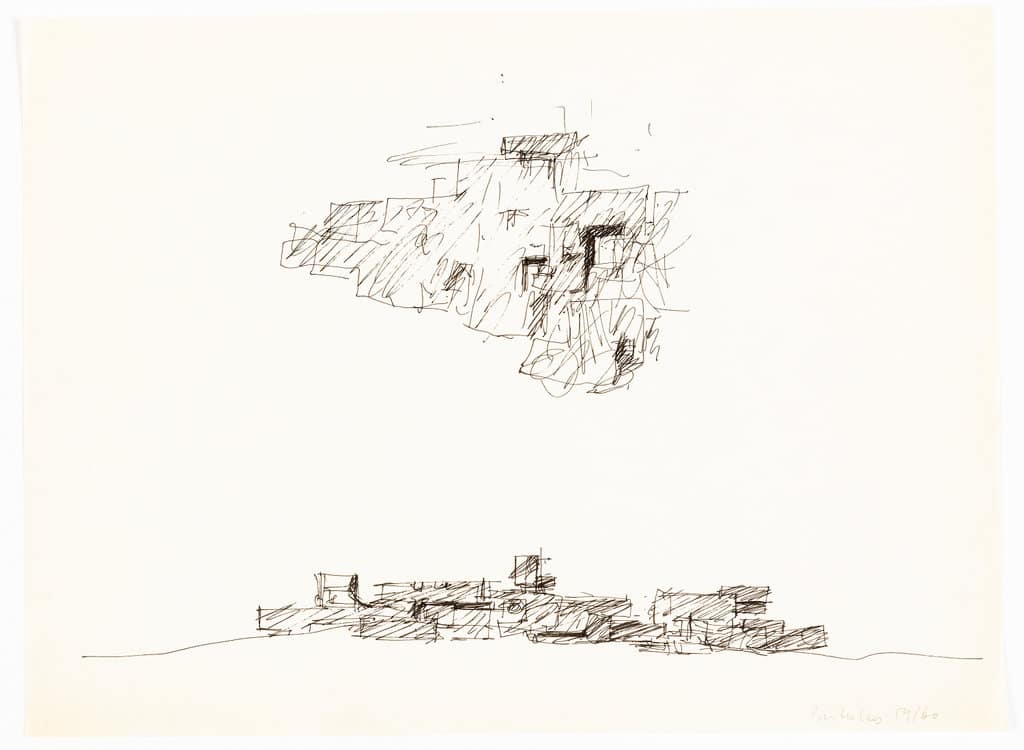

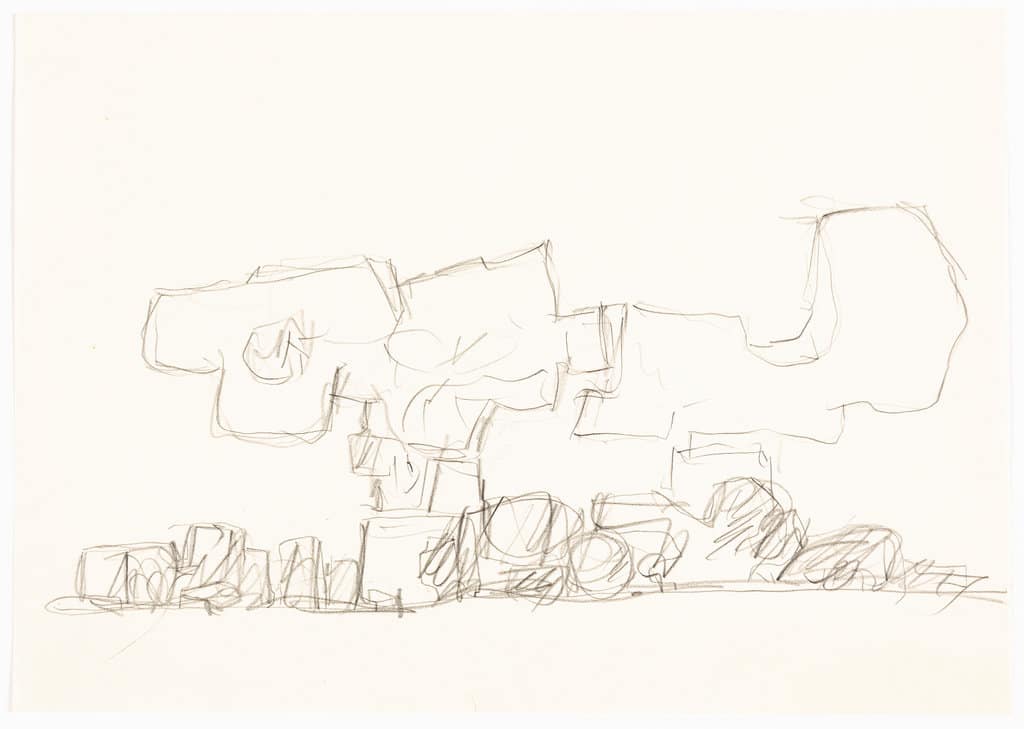

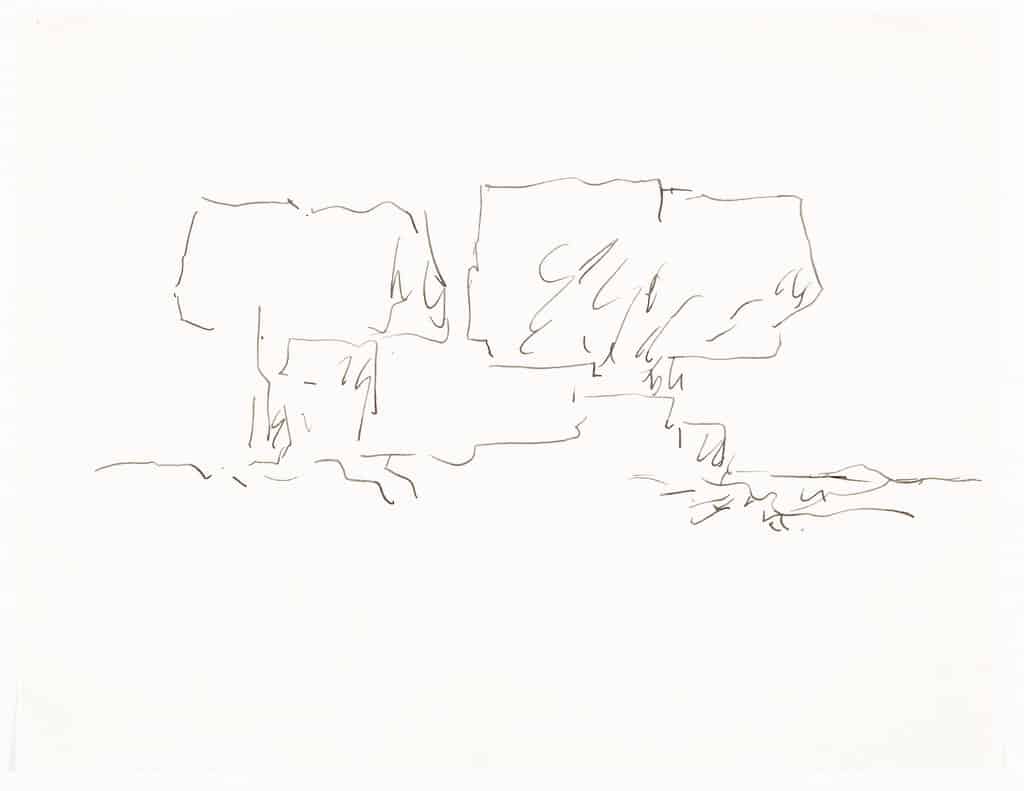

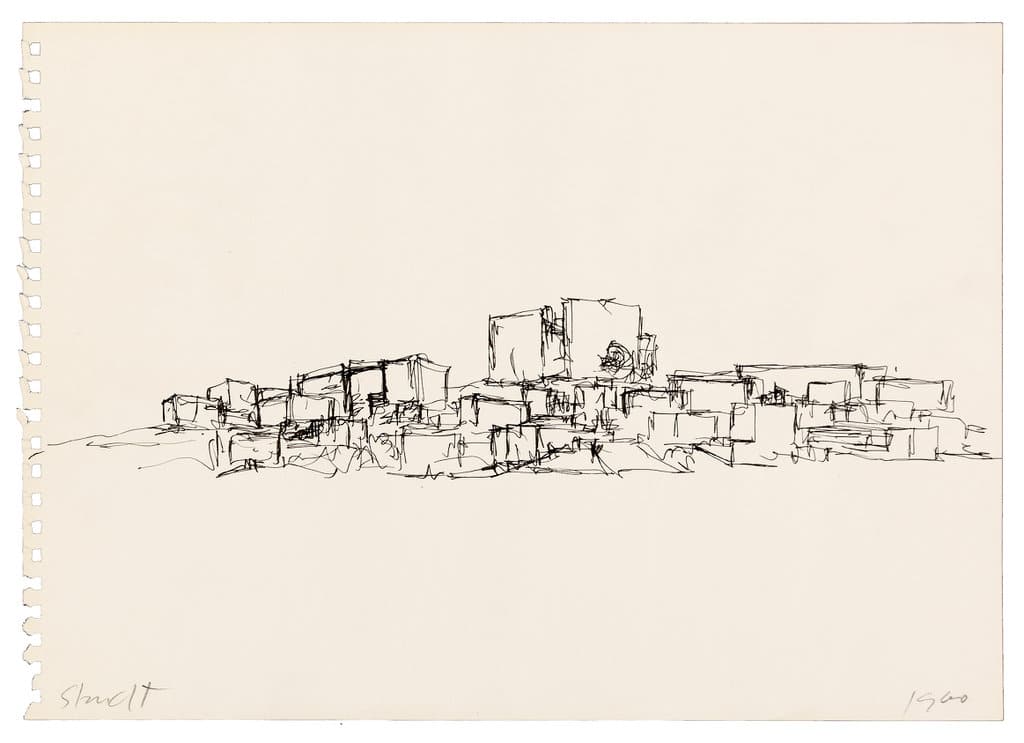

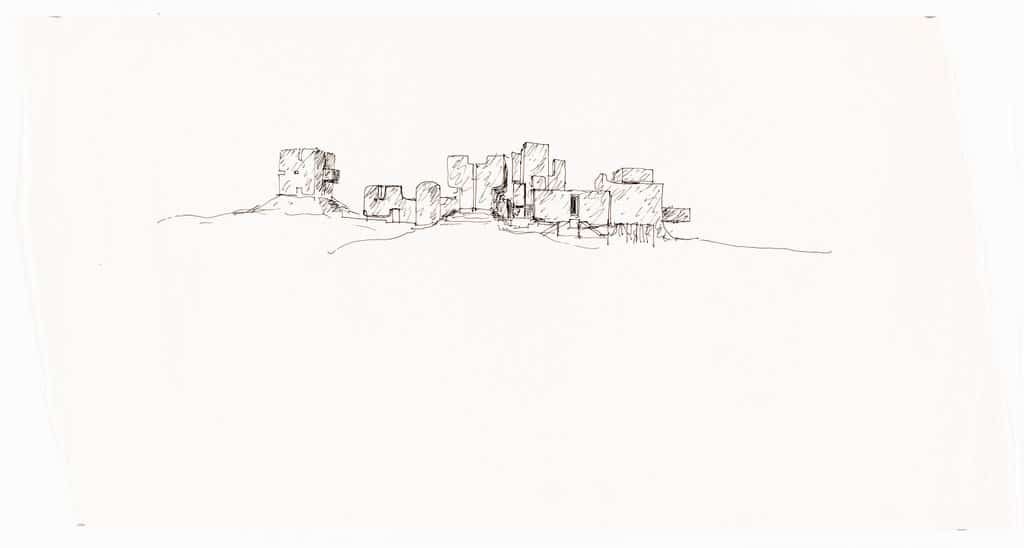

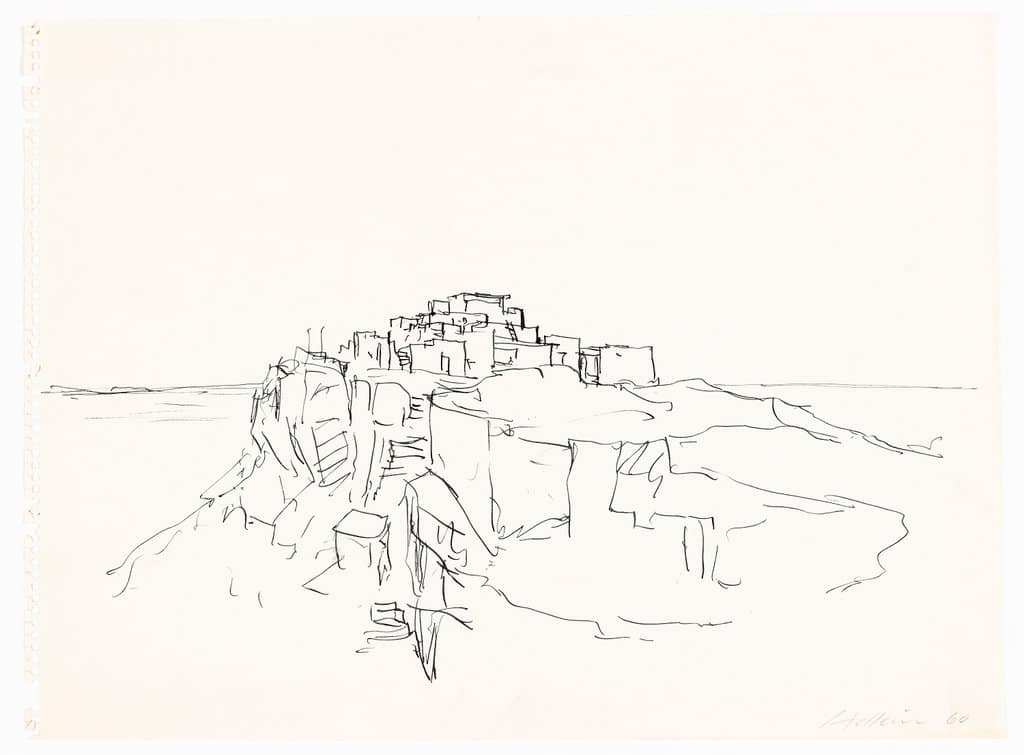

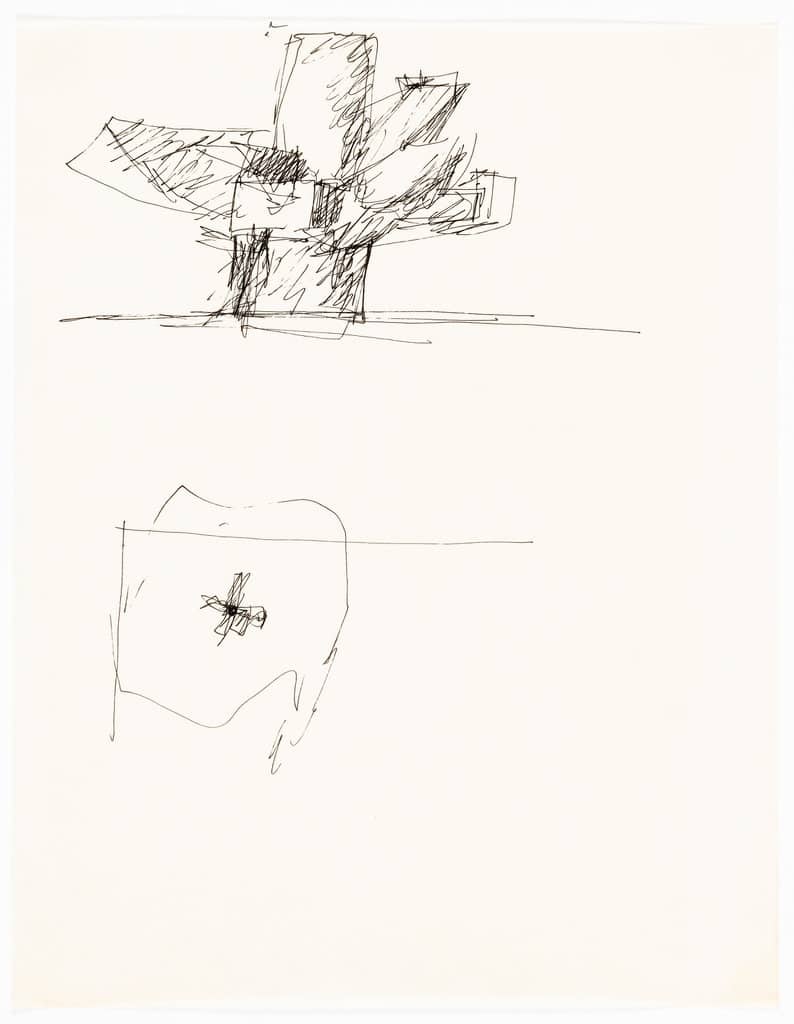

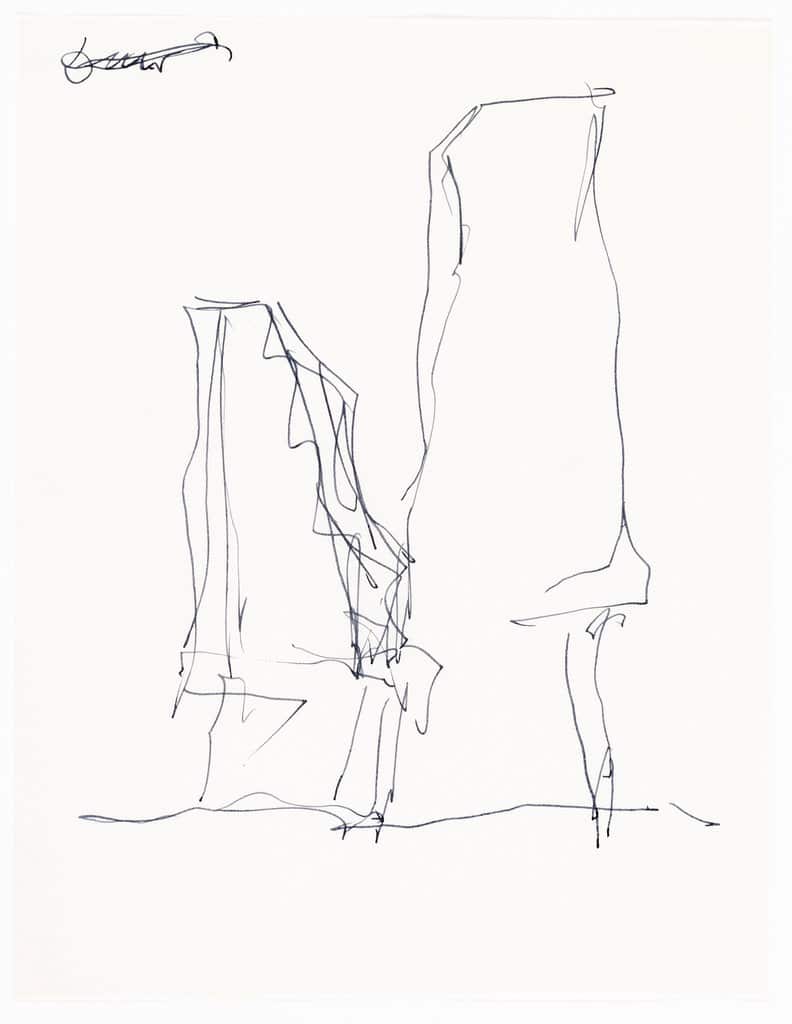

In propositional studies executed primarily through drawing, projects overlap so that the spatial inquiry becomes a continuous body of work moving from single objects placed in a landscape to vast urban clusters, often called simply ‘City’ or ‘Building’. These experiments include dwellings that might consist of communication cells, secluded enclosures or watch-towers; sacred spaces that would be constructed from the interstices between colliding monumental forms; ‘communication interchanges’; buildings that could take flight; entirely self-sufficient urban structures like the Mesa and Valley Cities Hollein imagined as he travelled through the American West; and the Underground City on which the two collaborated.

Asking questions rather than proposing solutions, their work falls across a deliberately uncertain line between art and architecture, the mechanistic and biomorphic, the domineering and humane, the ironic and ideal. Hollein in particular remained through his work, publications and correspondence, a central source of inspiration for the generation of architects aiming to reinvent their field.

– Constant