Hans Hollein & Spiritual Expression in Architecture

The defining characteristics of modern architecture took shape against a host of disorientating shifts in the 19th century. On the theoretical side, the instantiation and development of aesthetics as an autonomous realm strained a sacred harmony between beauty, truth, and goodness. On the practical side, technological, social, and cultural advancements wrenched apart a stable relationship between humanity and nature. All the while humanity was becoming conscious of a new kind of freedom which opened an incomprehensible horizon of possibilities for artistic creativity.

This new perspective from a world unhinged from the sun (as Nietzsche’s madman proclaimed) afforded art to be seen in a new light. No longer was its goal representation of the natural realm. It was, rather, expression of the human spirit.

The expression is exemplified in the group of post-impressionist painters appropriately referred to as the Expressionists. These included Cezanne, Gaugin, and Van Gogh among others, their quest often being discussed as the transposition of the emotion of the artist onto the subject matter of the artwork. They sought not to present objects as they were objectively seen, but to draw out a deeper meaning of their reality by emphasising the intangible or even spiritual qualities of an experience with them. This task is accomplished by skewing the linear aspects, flattening the forms, intensifying the colour palette, and overall distorting the views of the painting. In essence, the Expressionists’ decisive style was produced by the meeting of the artist’s innate spontaneity with the world of everyday life.

The Protestant theologian and philosopher Paul Tillich warned, however, that if the only expression taking place is the subjectivity of the artist, then the artist is only ‘like an adolescent who writes sentimental verses, without artistic validity,’ and the art becomes a shallow form of unbridled emotion.[1] He correspondingly expanded the definition of expressionism to include extra-subjective reality. It ‘refers to the artistic impulse…to break through the ordinarily encountered reality instead of copying it or anticipating its essential fulfillment.’[2] Expression is the moment when the divided world of human and nature, possibility and necessity, freedom and determination is united through a rupture. Art, in this conception, is a confrontation with being itself. It is a shift in reality, working through the human spark of creativity as it presents new possibilities to the world.

As such, it involves both a creative and disruptive aspect. The ‘expressionist element does something to reality; it breaks it; it pierces into its ground; it reshapes it, reorders the elements in order more powerfully to express meaning.’[3] It simultaneously breaks into the world and stitches it back together. It destroys as it creates; inaugurates possibilities as it disintegrates others. The dynamic collusion between these two forces—creativity and disruption—is what the Expressionists attempted to capture. And, by the first few decades of the 20th century, the expression of human spirit came to be present in nearly all forms of artistic endeavour, including architecture.

There were skeptics, of course, when it came to the possibility of expressionist architecture. Sigfried Giedion remarks with a preemptive confidence: ‘The expressionist influence could not perform any service for architecture.’[4] Regardless of modern advancements, architecture was resolutely bound to physics.[5] Even as technology produced innovative materials, the statics and dynamics of natural forces were surely too strong for humanity’s creative spirit to break through. Architecture was sentenced, one way or another, to ‘copy’ nature.

Yet, Giedion’s judgment has an even more profound insight buried within: it seems impossible to allow spontaneity to become present under the mathematically governed process of architecture. The very process of building involves moving from creative insights to the rigid world of precise determination, from bringing expressive chaos to material definition.

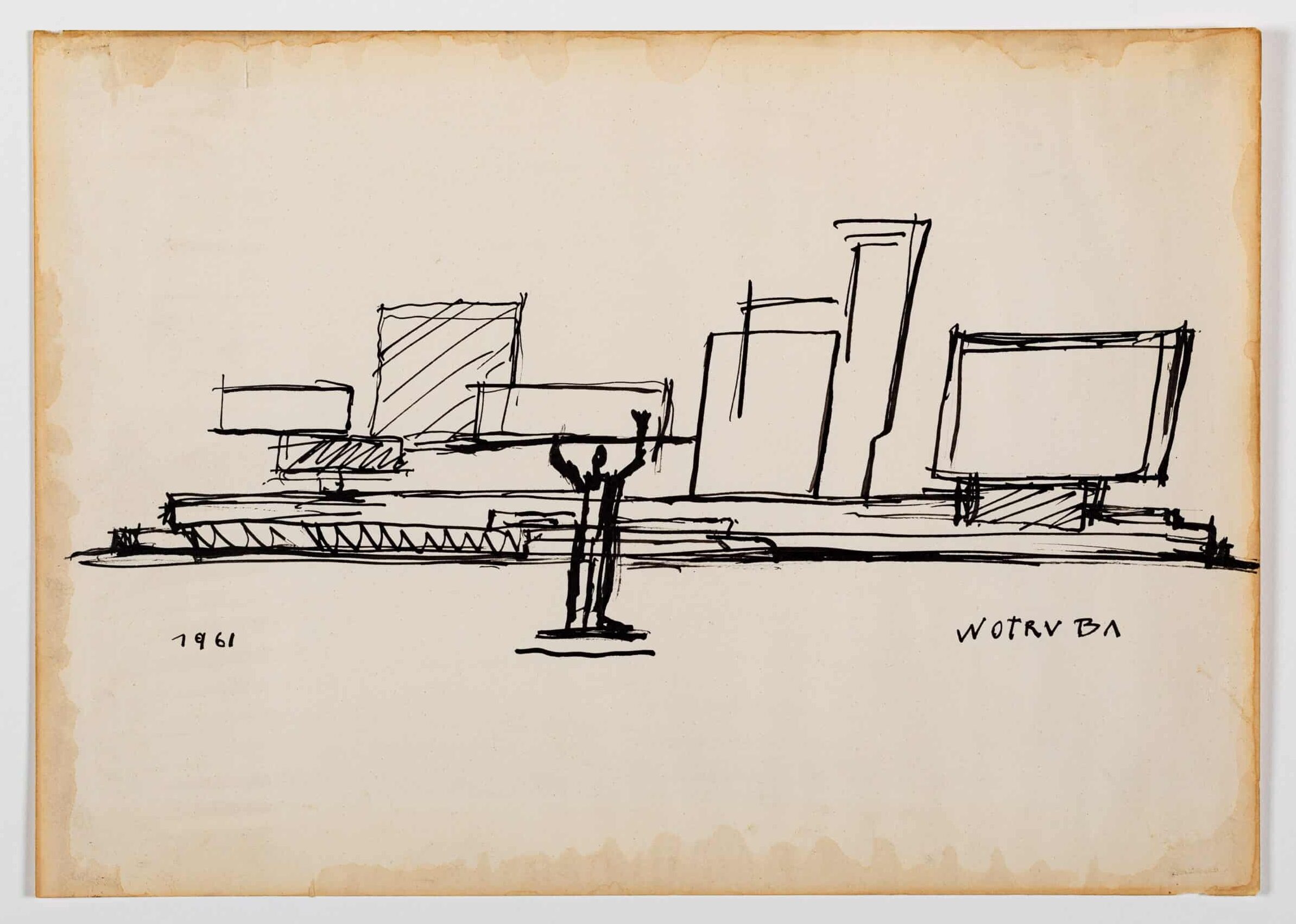

Perhaps, though, the spirit’s lasting influence was not in breaking through in the built world in defiance of its natural limitations, but, rather, in quietly creeping into design—doing so through architectural sketches.

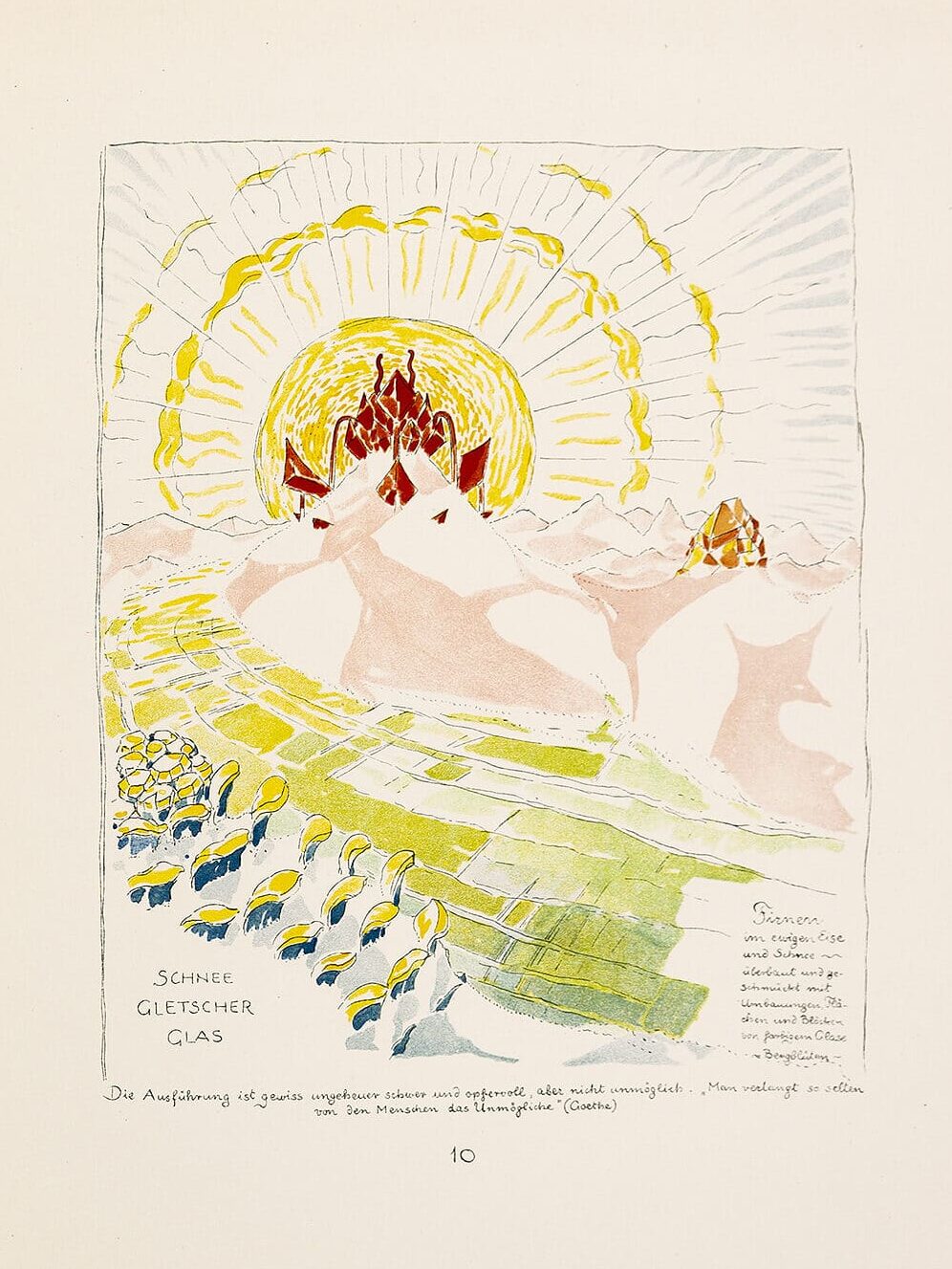

There are the more obvious examples of designers who played a formative role in what came to be recognised as a moment of expressionism in architecture. Bruno Taut, for one, epitomised many of the defining features of the expressionist painters. His sketches present a world beyond nature while simultaneously being grounded in nature. It is an ‘alpine architecture,’ pushing the grand adventurism of mountaineering to new heights in building. All the basic features of expressionist art are developed into this more-than-natural state, such as considering colour a material in itself.[6]

But there are also several expressionist intonations to be had in the second half of the 20th century. Hans Hollein, in a key lecture from 1962, emphatically claims that ‘architecture is a spiritual endeavour, realised through building.’[7] It is the ‘expression of man himself—at once flesh and spirit.’[8] The ‘expression’ strives to indicate an irreducible spontaneity of spirit, the seat of human creativity. It is what most powerfully discloses the escape of humanity from the determinative machinery of cause-and-effect in the natural world. Something approaching Tillich’s notion of expressionism is at play here.

The linking of spontaneity to spirit has deep roots in modern aesthetics. It seemingly originates in Immanuel Kant’s earthshaking Critique of the Power of Judgment, and receives decisive developments in the German Idealists, especially in F.W.J. Schelling and G.W.F. Hegel. A key advancement in these thinkers is the shift from the Aristotelian-based metaphysics of substance to the modern metaphysics of subjectivity. Here, the basis of reality was no longer understood to reside in a stable, eternal, and incorruptible core of all entities, but in the dynamic expression of an Absolute subject, who moves all dimensions of reality—history and thought, culture and truth, essence and existence—through an exertion of will.

In fact, by the middle of the 19th century, the categories of spirit, will, and reality (being) collapse into each other. It is in this vein that Arthur Schopenhauer, in World as Will and Representation, says that the expression of spirit (as will) is the ‘highest aim of art’ and that, in its unique expression, architecture brings to lucid perceptiveness the most basic ideas of the ‘will’s objectivity.’[9] These include aspects such as natural forces (gravity) and properties of natural materials (rigidity, hardness). In this reasoning, we only understand these features of reality through the expression of will in architecture. We learn what gravity is through attempts to defy it. Spirit thus not only lives beyond the cold determination of nature; it makes natural processes intelligible through its unique freedom.

When Hollein declares that architecture is about a ‘spiritual endeavor’ he has his feet firmly planted in this tradition. Architecture is about bringing the spontaneity of spirit to spatial expression. It is not about beauty, not about proportion or form. ‘Architecture is cultic, it is time [Mal], symbol, sign, expression.’[10] And, it does so through an exertion of will: over order, over technology, over nature. ‘Architecture is elemental, sensual, primitive, brutal, terrible, mighty, dominating.’[11]

An issue arises, however, within the subjectivity of the architect. Spirit is spontaneous even to will. It is always out ahead of any control, always leading in unpredicted directions. In light of this spontaneity, the will struggles to merely be intentional, much less to remain effective in bringing about its ends. A primary task of the artist is to capture the spirit, to catch a glimpse of its fire, to hold it in its hands without getting burned. Expressionists sketches seem to be a means for this ‘capturing’ to occur.

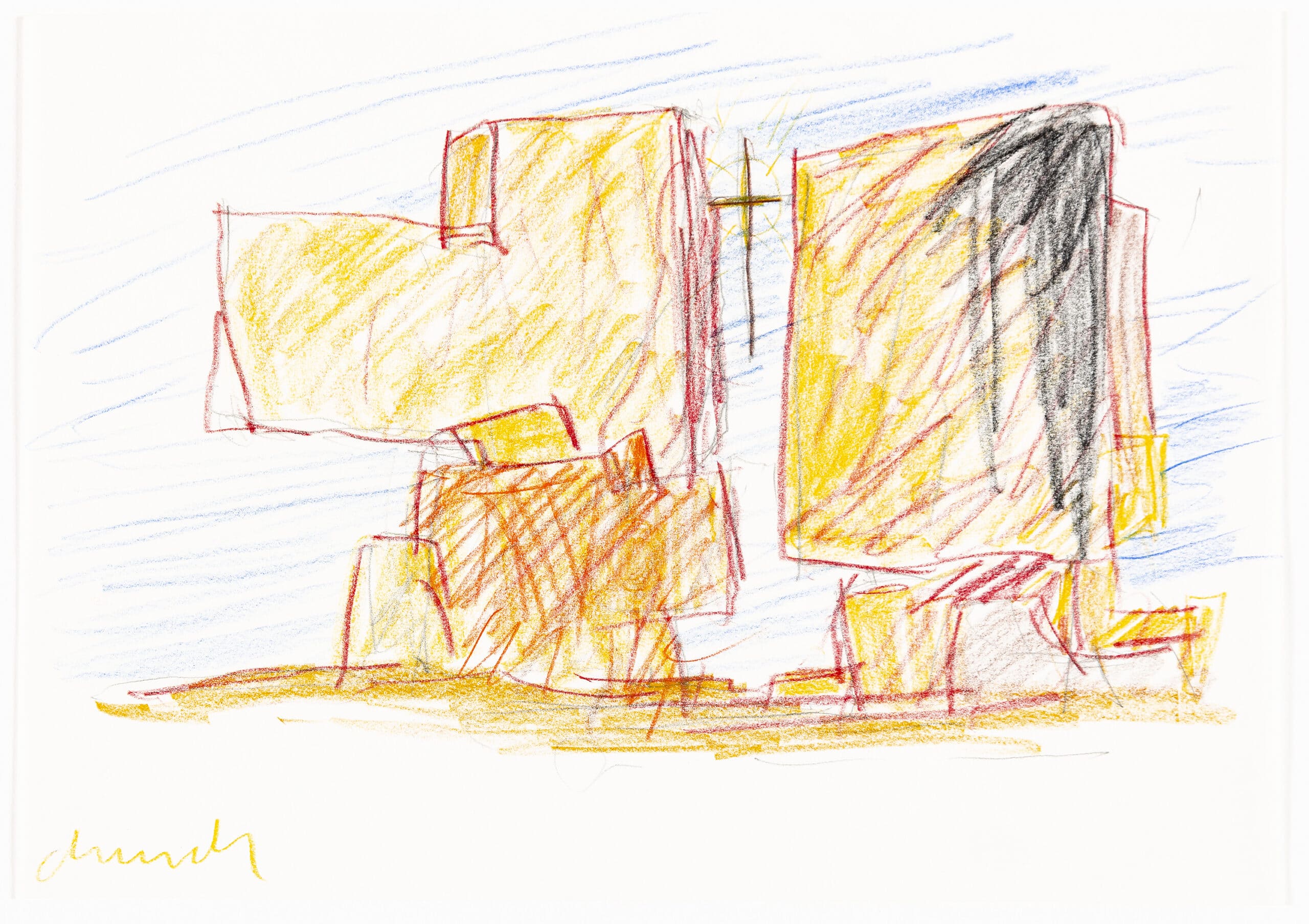

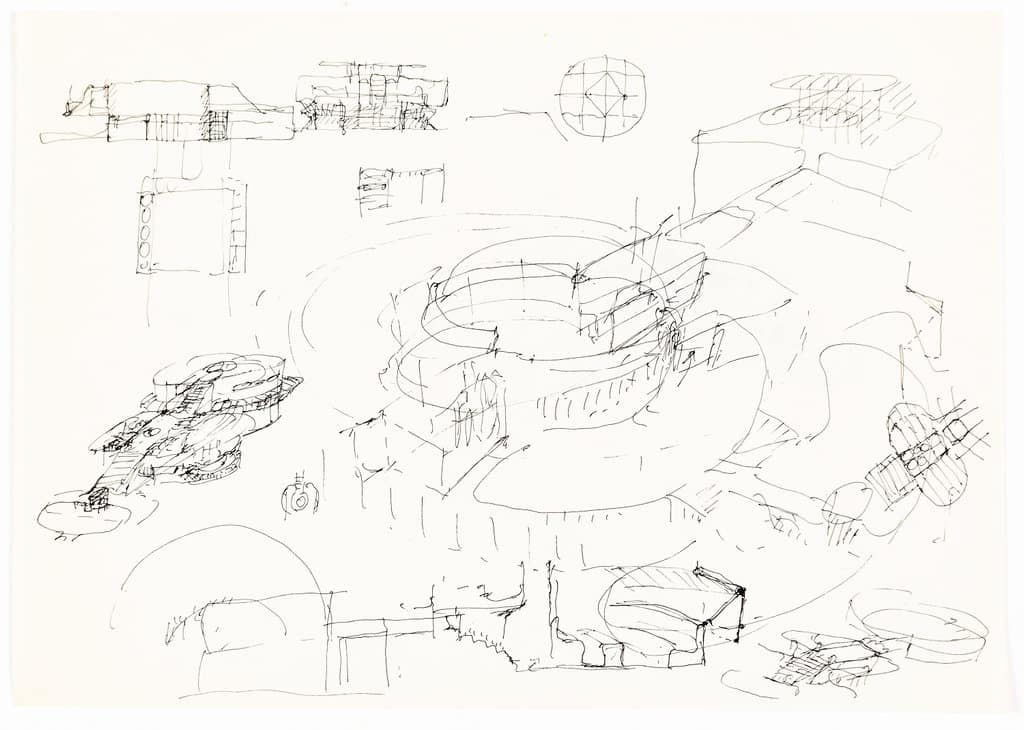

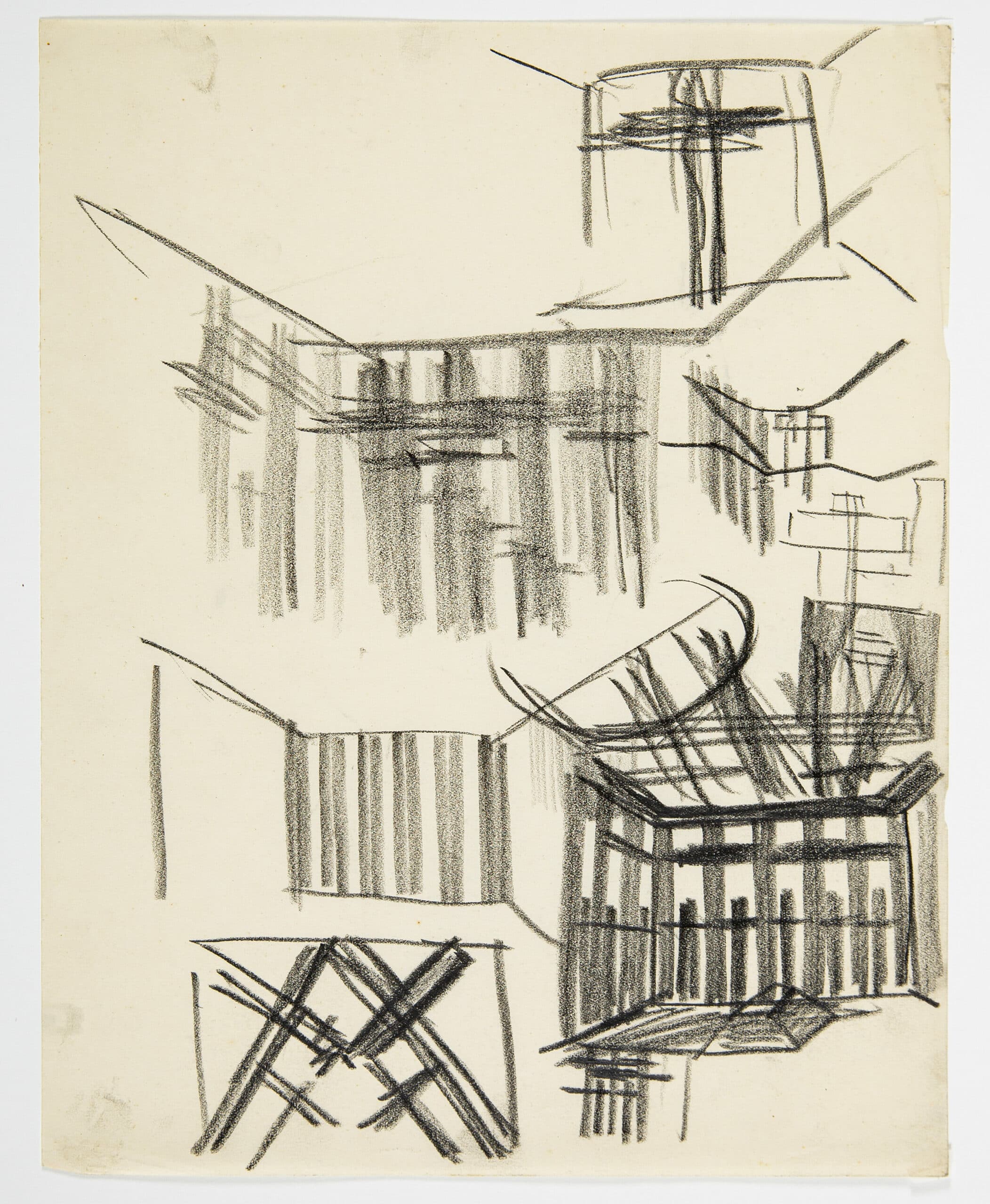

In Hollein’s sketches, lucid glances of the spirit’s radiance take place. One of the more obvious (and explicit) glimpses erupts in a sketch from the 1960s that coincides with a series of purposeless explorations of ecclesial design.[12] The sketch has an overall presence of expressionist style: there is a frantic excitement in the pencil marks, reminiscent of Van Gogh’s brush; the forms are flattened in Cézanne’s characteristic manner; and masses themselves are even brightly coloured in orange and red in the vein of Gaugin, highlighting the dynamics of the material’s finish as much as values of shadow and light. At the centre of the composition, a cross floats between two large architectural masses.

Too much should not be drawn from Hollein’s specific symbol of a cross and expressionism in Tillich’s sense. Less important is the kind of symbol; and even less any connection to a defined religion. More important is what a symbol does: it disrupts through creative force. It breaks into reality. And, in doing so, it stands as the foundational core of the artistic expression.

In Hollein’s sketch this is most evident in the way the building forms around the symbol. The architectural forms submit to the cross’s disruption. The materiality of the building parts to open space for the symbol’s presence. It appears to push its way forth from behind the forms, disrupting some original balance and harmony for a more precarious arrangement. Those with the smallest mass support those with the largest, all of which held impossible together in a conglomerate of cantilevers. The overlap between the cross and the structure on the left even makes it seem this exertion is happening now, actively, in the sketch.

Equally so, that the symbol is expressive of human spirit, and not mimetic of nature, is apparent in the gestures of light of this sketch. The cross is adorned with a halo and emits a glow. The symbol radiates out from itself; but the light does not follow. It stubbornly shines from the left foreground, neither toward nor away from the symbol. Light effectively disregards the cross. But, everything that the light touches has been radically shifted according to its eruptive value.

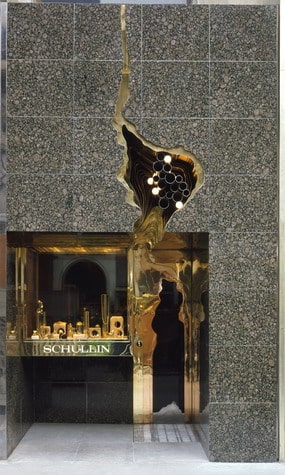

The disruptive force of expressionism can also be seen in Hollein’s built works. The Schullin I jewellery store (1974) is a clear example, as a sculpture erupts from within, nearly tearing the façade in two. The Retti candle shop (1965), as well, presents a ruptured storefront, although in a less dramatic (or, more controlled) fashion.

The point is that the expressionism evident in Hollein’s sketches has, in a sense, been preserved in his built works. They have become defined in stone and steel. Perhaps the dynamism of the subjective elements—the excitement, the surprise, even the accompanying fear—has been muted in this built form; but the original impulse remains.

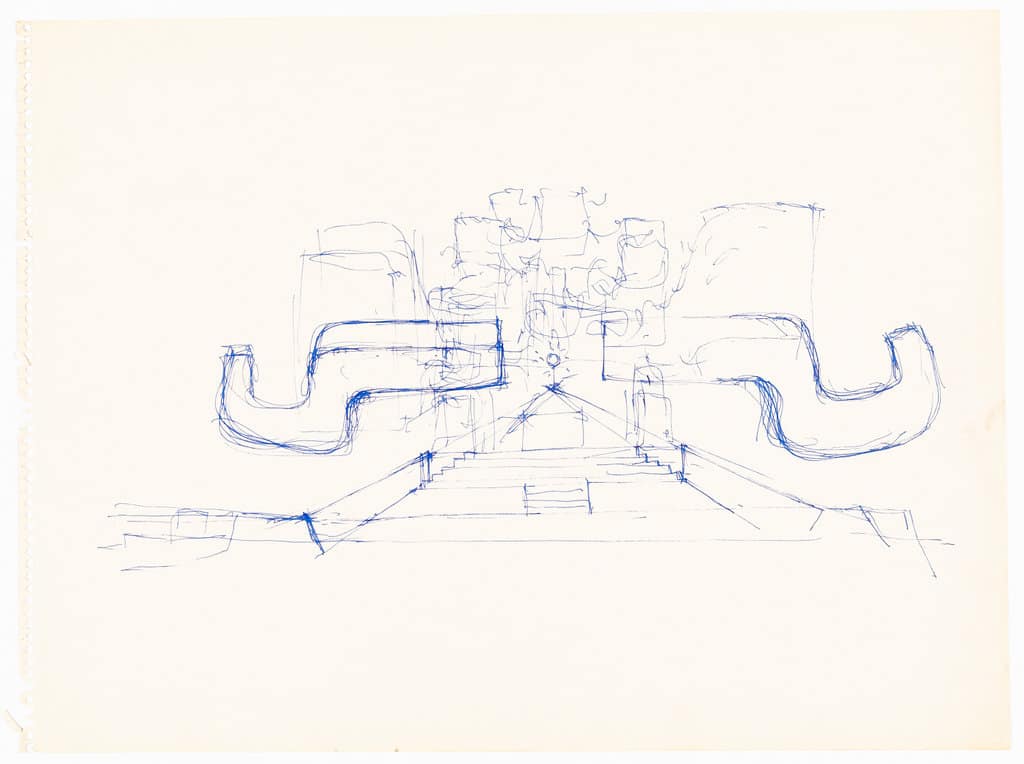

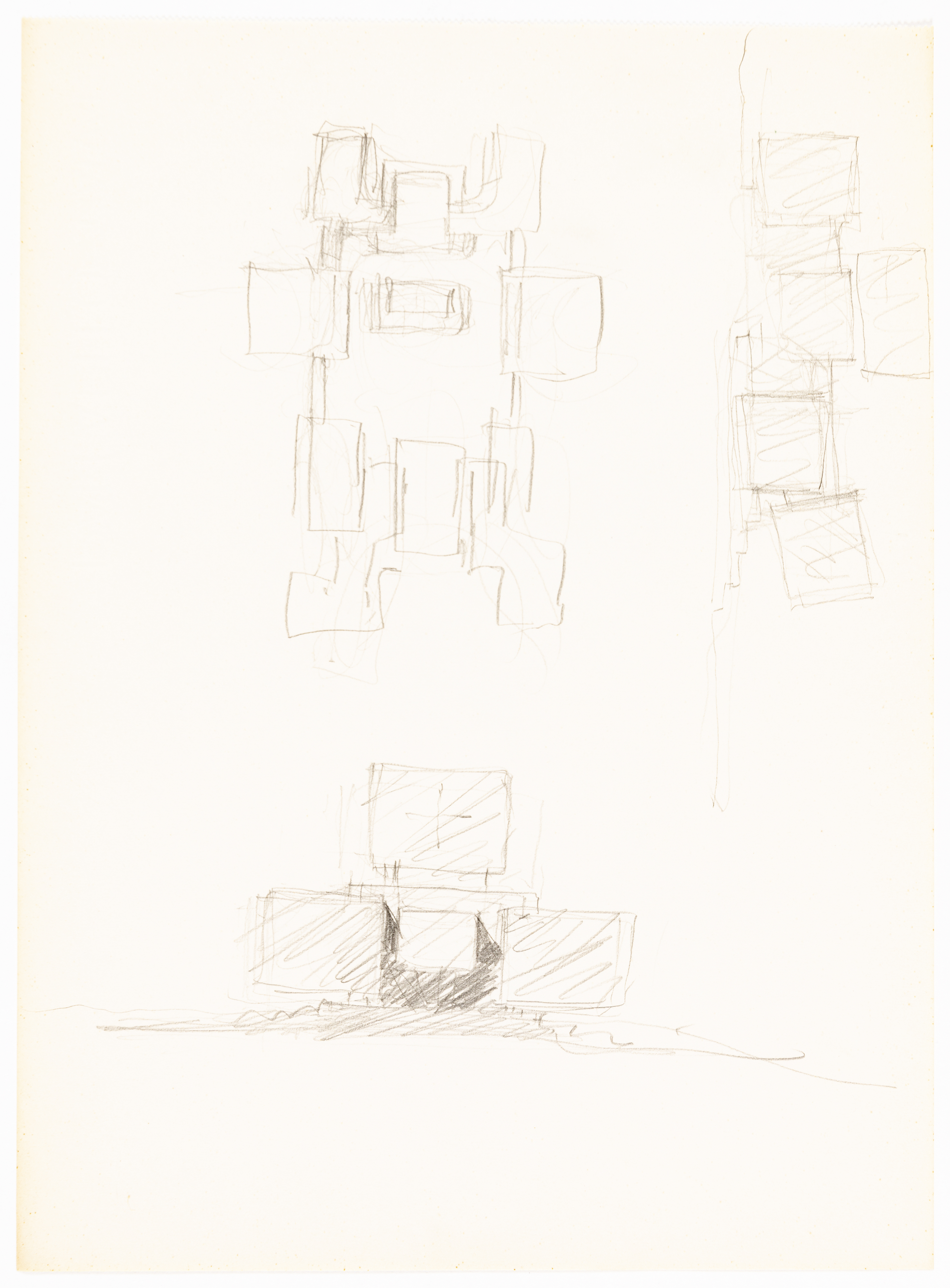

The dynamics of creation and disruption are what makes sketches what they are. A sketch is intentionally careless. It does not hesitate to not be certain. It happens almost as quick as the creative interruption, and can send creativity and all its final determinations in unexpected directions. In this way, sketches even help to shape the will, to bring artistic expression to a sharper focus. They retain spontaneity. And, in doing so, sketches reveal their permanence in the built world.

C.M. Howell is a PhD candidate in theological aesthetics at the University of St Andrews.

Notes

- Paul Tillich, ‘Visual Arts and the Revelatory Character of Style,’ in Paul Tillich: On Art and Architecture, ed. John Dillenberger and Jane Dillenberger (New York: Crossroad, 1987), 132.

- Tillich, ‘Excerpts from Systematic Theology,’ 159.

- Tillich, ‘Religious Dimensions of Contemporary Art,’ 177.

- Sigfried Giedion, Space, Time and Architecture: the growth of a new tradition, 5th ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), 486.

- Wolfgang Pehnt, Expressionist Architecture, trans. J.A. Underwood and Edith Küstner (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 8.

- Deborah Ascher Barnstone, The Colour of Modernism, Paints, Pigments, and the Transformation of Modern Architecture in 1920s Germany (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021).

- ‘Zurück zur Architektur,’ 1962, accessed 22 July, 2023, http://www.hollein.com/index.php/eng/Writings/Texte/Zurueck-zur-Architektur.

- Hans Hollein, ‘Walter Pichler/Hans Hollein: Absolute architecture,’ in Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-century Architecture, ed. Ulrich Conrads (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1964), 181.

- Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Presentation, vol. I (New York: Routledge, 2016), 210; 4.

- ‘Alles Architektur,’ 1967, accessed 2 August, 2023, http://www.hollein.com/index.php/eng/Writings/Texte/Alles-ist-Architektur.

- Hollein, ‘Absolute architecture,’ 181.

- Cf., Eva Branscome, Hans Hollein and Postmodernism. Art and architecture in Austria, 1958-1985 (London: Routledge, 2018), 137.

From the Drawing Matter collection: architectural expressionism and the cross as symbol. Register for full access to the catalogue here. – Eds.

– Nicholas Olsberg