John Lautner: House and Studio for Edgar Ewing

On presenting himself as a potential apprentice at Taliesin to Frank Lloyd Wright Jr., Lautner heard no objection except the sly comment that he would be ‘too big for the rooms’. Everything about his approach to visualising a design speaks to the distance from which this towering figure saw the world, reading a site at the scale of a painting, structure as the triangulation of larger earthly geometries, and shelter simply as the cover from which to study a vast horizon.

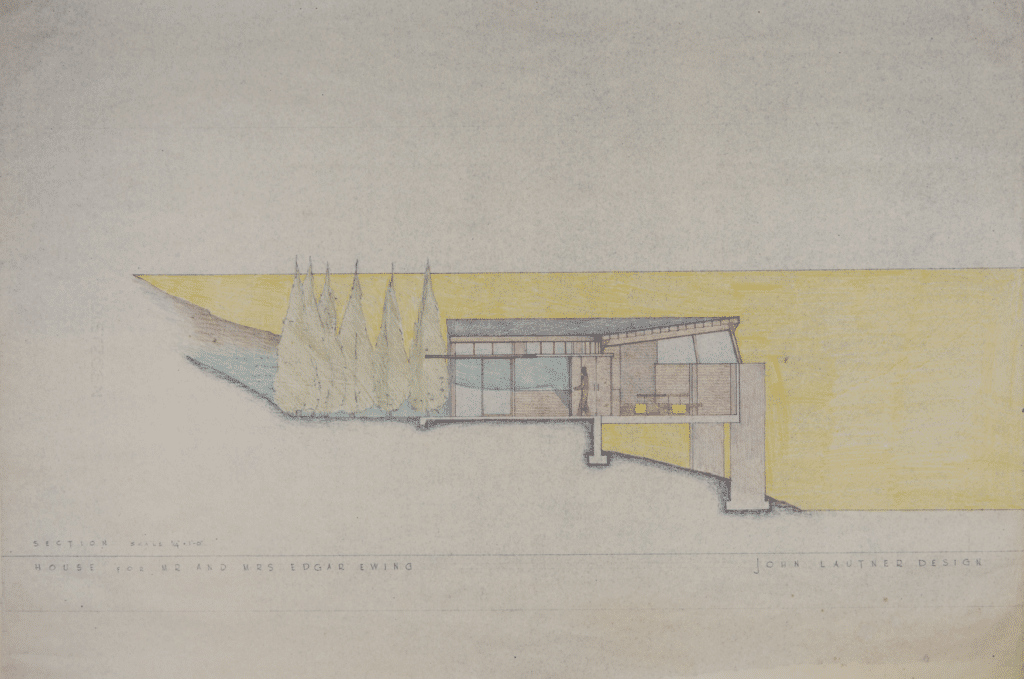

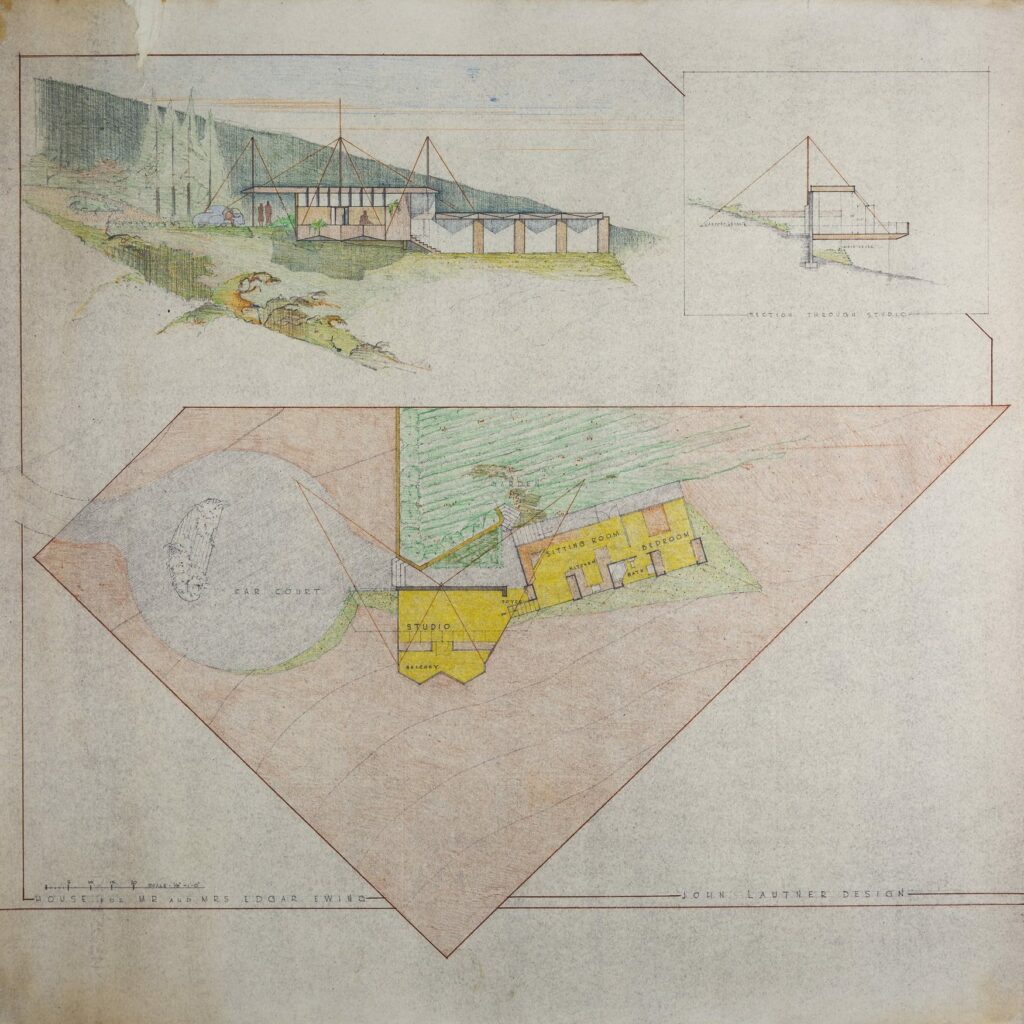

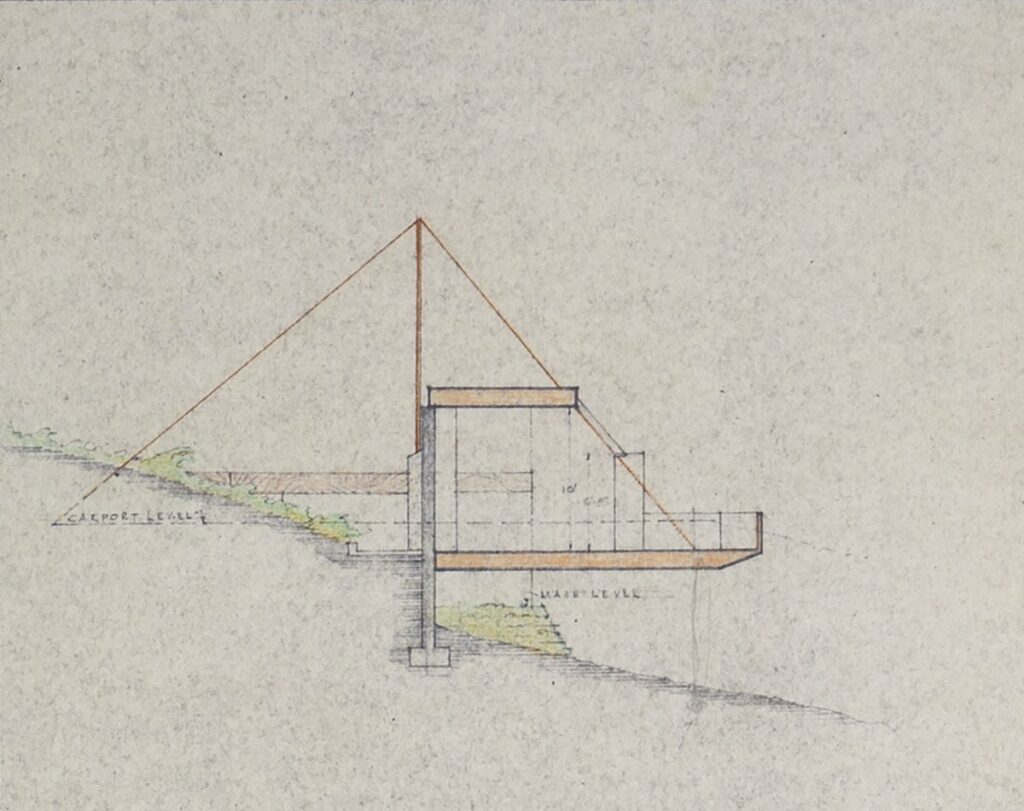

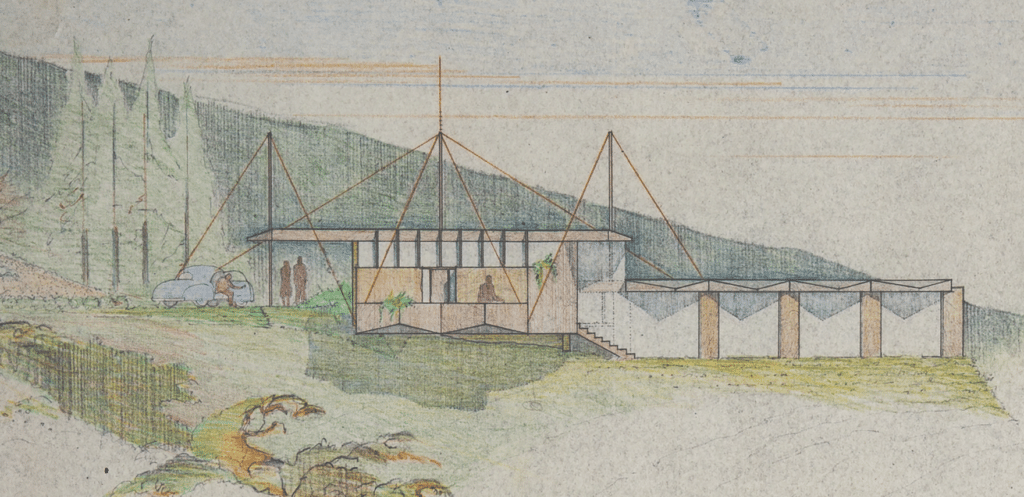

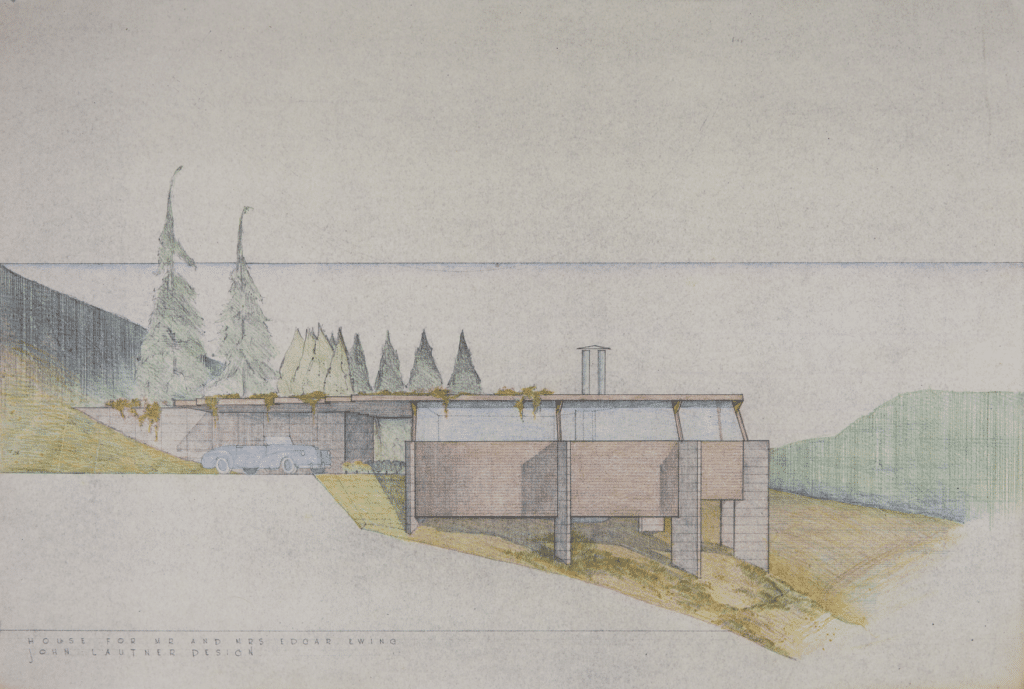

Lautner’s first set of drawings for a studio and home for the painter Edgar Ewing appear on a single sheet. Driven by a combination of material shortages, a vast building boom, the need for rapid construction, and the availability of virtually unbuildable precipitous and unstable hillside sites, the design draws upon engineering and fabrication techniques developed in the flourishing local aerospace industries, and on many of the surplus materials discarded by them. It is the last in a series of houses, each radically different in plan, in which Lautner used masts and stays to suspend the roof, so that walls could be constructed in lightweight materials; light, air and vista maximised; floors simply floated above the ground; and foundations reduced to a minimum.

Lautner’s studio drawings can, like the man himself, be sometimes more blunt than graceful, but they almost invariably carry two eloquently stated hypotheses: one pragmatic and the other ideal. Here the different segments of the drawing make the practical and ingenious economy of the scheme apparent through site plan and section, while the elevation renders the resulting transparency and the diagonal relationships between the structure, the fall of the land and the cast of the sky in transcendental terms. At the same time, the broken pentagram laid out in the graphic arrangement of the three segments on the page suggests that the building is simply participating in a large and subtly constructed geometry of the sublime, in which divisions and multiplications of the 15-degree angle serve as a kind of modular breakdown of the path to infinity.

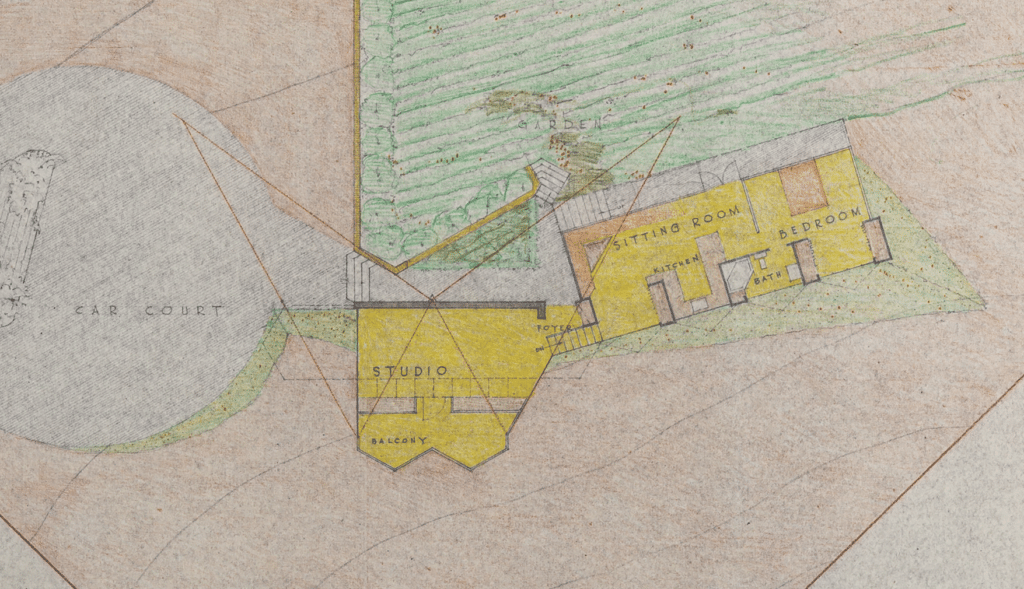

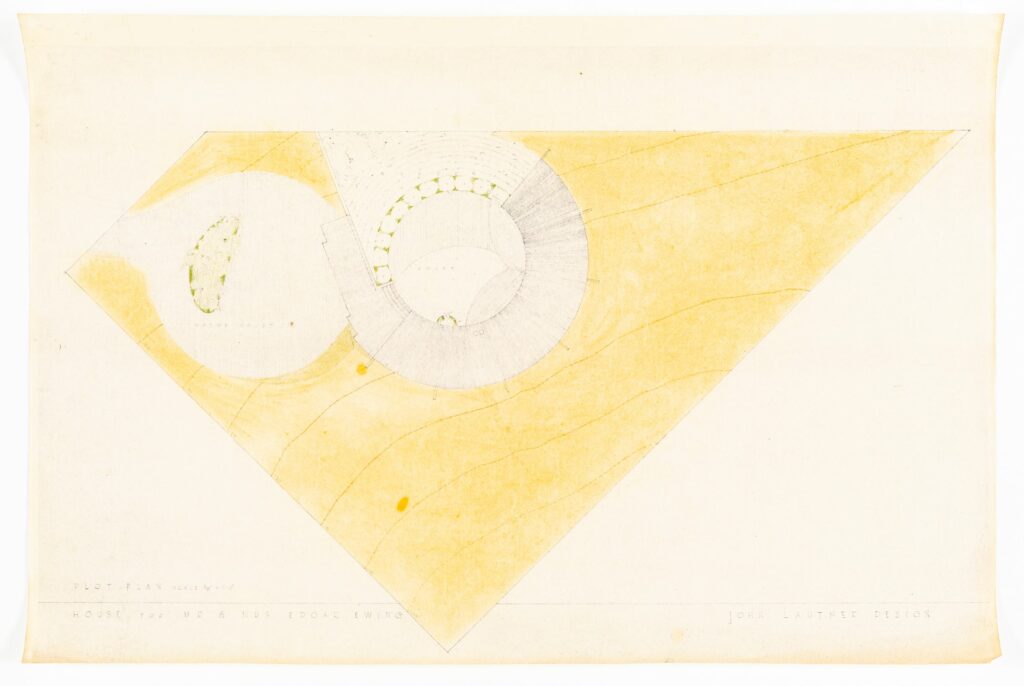

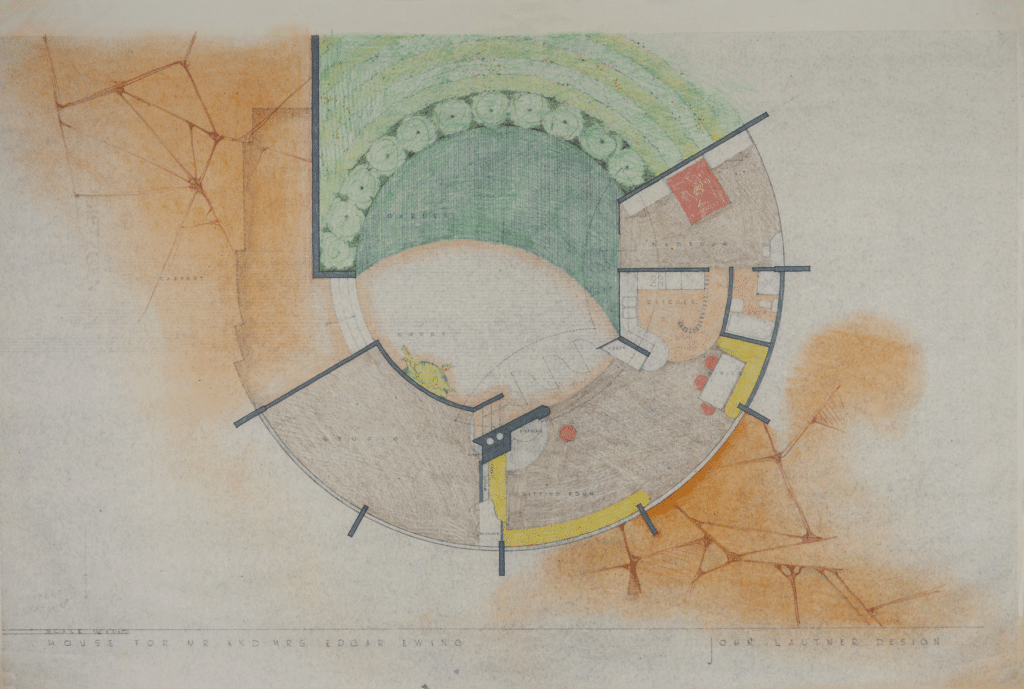

Lautner’s second scheme was probably drawn up as the great steel strike and Korean war rearmament restricted the use of metals and lumber in housing, and it follows a very different pattern. Now looking (as the site plan expresses) at the contours rather than the lines of the site, Lautner uses overlapping fragments of circles and interspersed drums – at fourteen different radial scales, from the planting terraces and awnings to the chimney funnels, cabinets and chairs – to organise a more substantial, supported rhyming structure and to orchestrate the landscape around it. A more detailed plan makes an entirely different analysis of the topography, setting the circles not within the curved and moulded surface of the terrain but in counterpoint to the underlying geological geometries. Here vivid red lines emphasise the angularity of what lies beneath, drawing attention to the tiny rings that form as the facets of the rock converge – and which establish the circular principle governing the design – as well as to the slopes of the crystalline, which Lautner echoes in the canted window walls.

Neither of Lautner’s schemes was ever built, and the drawings remained with the clients. Some years later, Ewing’s dealer happened to meet the architect during a long layover in a distant airport. Captivated by the passion with which Lautner talked about architecture, and by a vision as large as the frame that housed it, he suggested that Ewing gift him the drawings in lieu of an unsettled account. They have since been sleeping quietly for sixty years.

We post them here in honour of Karol Lautner Peterson (1938-2015), who did so much to keep her father’s legacy of reinvention – with its passionate commitment to finding an architecture that could match the changing terms of the times to the unchanging logic of the earth – so vividly alive.