L’architecture des réalités mises en scene: (re)construire Disney

Drawing Matter asked Fabrizio Gallanti, Director of the arc en rêve – centre d’architecture, for an informal commentary on the content and presentation of their current exhibition L’architecture des réalités mises en scene: (re)construire Disney, open until January 2025.

We are arc en rêve. We do exhibitions. In Bordeaux, South-West of France. Somehow, they’re about architecture. We don’t cater just to architects. Our current show is very green. It is very curvy. The show is not just green, it is Go Away Green. If you squint your eyes some of the curves might look familiar. Yes, Mickey’s ears but anyway there is a large inflatable head in the entrance giving that away. You get lost in our gallery, but that was the intention. The exhibition that you find inside our venerable main gallery, built in stone exactly 200 years ago, is titled L’architecture des réalités mises en scene (re)construire Disney. In French that is, because we are a French institution. The building where our galleries are located, used to be a warehouse for goods coming to the Bordeaux port from the French colonies, in the Caribbean islands and Africa: it is known as l’Entrepôt Lainé. Entrepôt means warehouse, Lainé comes from Joseph Louis Joachim Lainé, a minister of Louis XVIII, who commissioned it. That Lainé came from a family of slave owners, based in Saint-Domingue, Haiti since the independence in 1804.

The exhibition in our Galerie Principale is curvy, because we designed and then built curved walls, extrapolating our floorplan from the shape of the head of Mickey Mouse, notoriously composed of three circles. And then we painted the plywood walls with the same colour that is used across Disney’s theme parks for their technical facilities. They patented it: Go Away Green. Some visitors wrongly assume that it is the colour for green screens, used for CGI or weather reports on TV. Actually, it is not. The Disney corporation has mobilized behavioural researchers and engineers to come up with a hue that makes the buildings where trash is kept or machines pump out heating and cooling almost invisible to your eyes, that instead are so-so attracted by Winnie the Pooh doing a photo-op with raving kids. We learned this fact and so many more from the curator of the exhibition, Saskia van Stein. She’s Dutch. She teaches at the Design Academy in Eindhoven. She is the director of the Rotterdam Architecture Biennale. She knows a lot about Disney. Disney the corporation. But also, Disney the man, Walt Disney. And his brothers, Raymond and Roy, who were so important for the company to thrive before and after Walt’s death.

When Saskia was a kid, living in Iraq because her parents worked there, she watched over and over the Silly Symphonies short animations issued by Walt Disney Productions between 1929 and 1939, using a Super-8 projector. She told this anecdote to the audience gathered for the opening lecture of her show, last March. In the exhibition, we project some of these short animations, also because they are copyright-free and in the public domain, since just a few years ago—nobody wanted to deal with the lawyers at Disney. L’architecture des réalités mises en scene (re)construire Disney stems from the long-standing interest by Saskia van Stein in the persona of Walt Disney and in the ways with which his legacy has infused the development of the largest entertainment company in the world. She is pursuing a PhD on that topic. The concept at the core of her ongoing research, which makes it a crucial contribution to the architectural field, is composed of two symmetrical elements. The first is that in the creation of the Disney identity, Walt was heavily influenced by his exposure to historic buildings, first discovered during the eleven months spent in Europe, just after the end of World War 1, as a driver for the Red Cross Ambulance Corps. The mixture of rococo references, the appropriation of old European fairytales and folk stories, the Bauhaus-style design for the studios in Burbank, inaugurated in 1940 and the usage of advanced techniques for animation, editing and sound created a unique identity for the Disney corporation.

The second element is that the brick-and-mortar operations of the Disney corporation, starting from Disneyland that opened in 1955 in Anaheim, CA, until today with 12 theme parks in USA, Europe and Asia and Disney cruise ships and Disney resorts and hotels have had an impact on the ways with which architecture, design and urban planning operate. Wandering through the exhibition and registering the reactions of the public, one can say that Disney has an even stronger influence on our psyche. The power of influence can be attributed to one neologism, coined in 1952 when Disneyland was being developed, ‘Imagineering,’ a registered trademark: how to engineer the imagination of consumers, an intention that has become persistent in the current late capitalist era. Does the word ‘experience’ ring any bells?

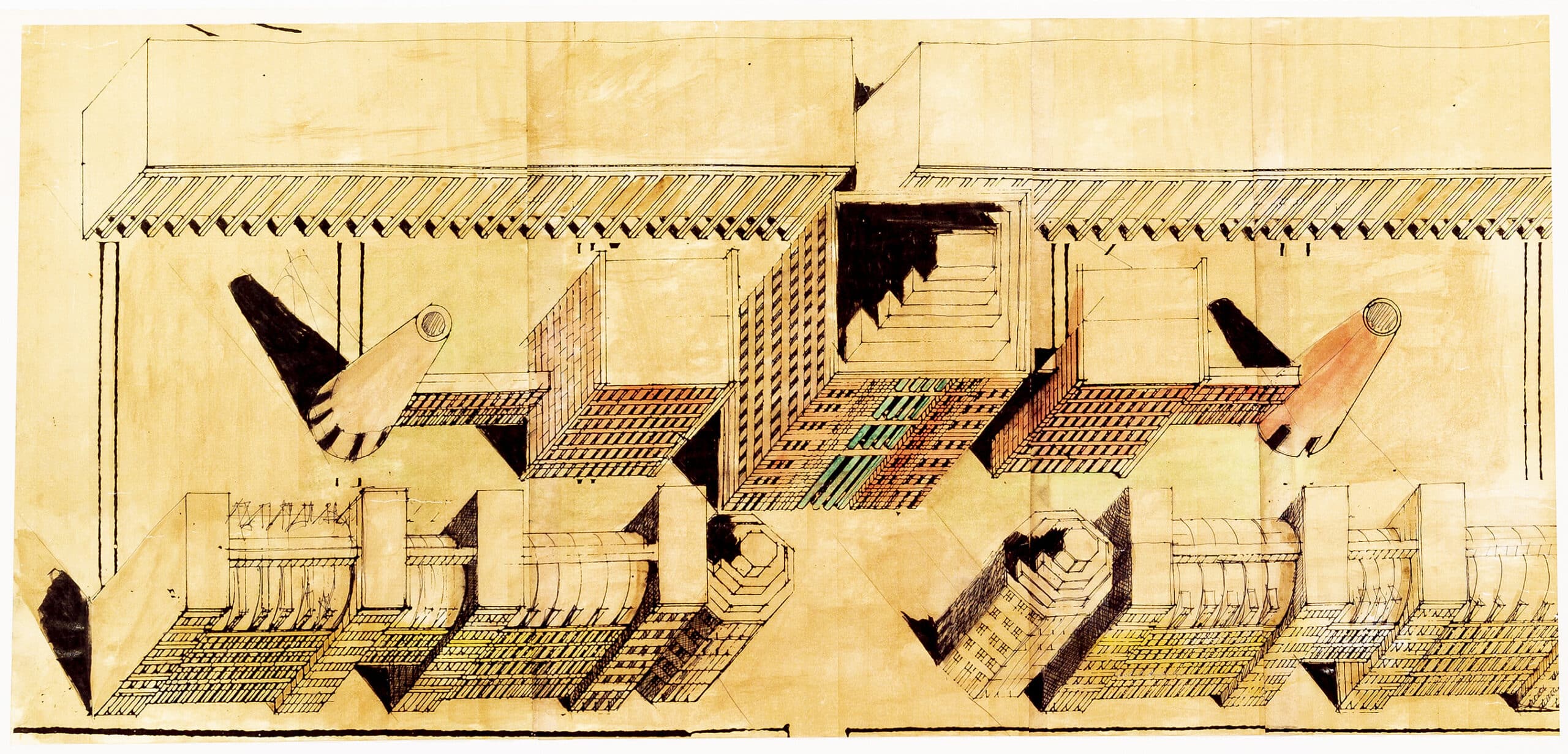

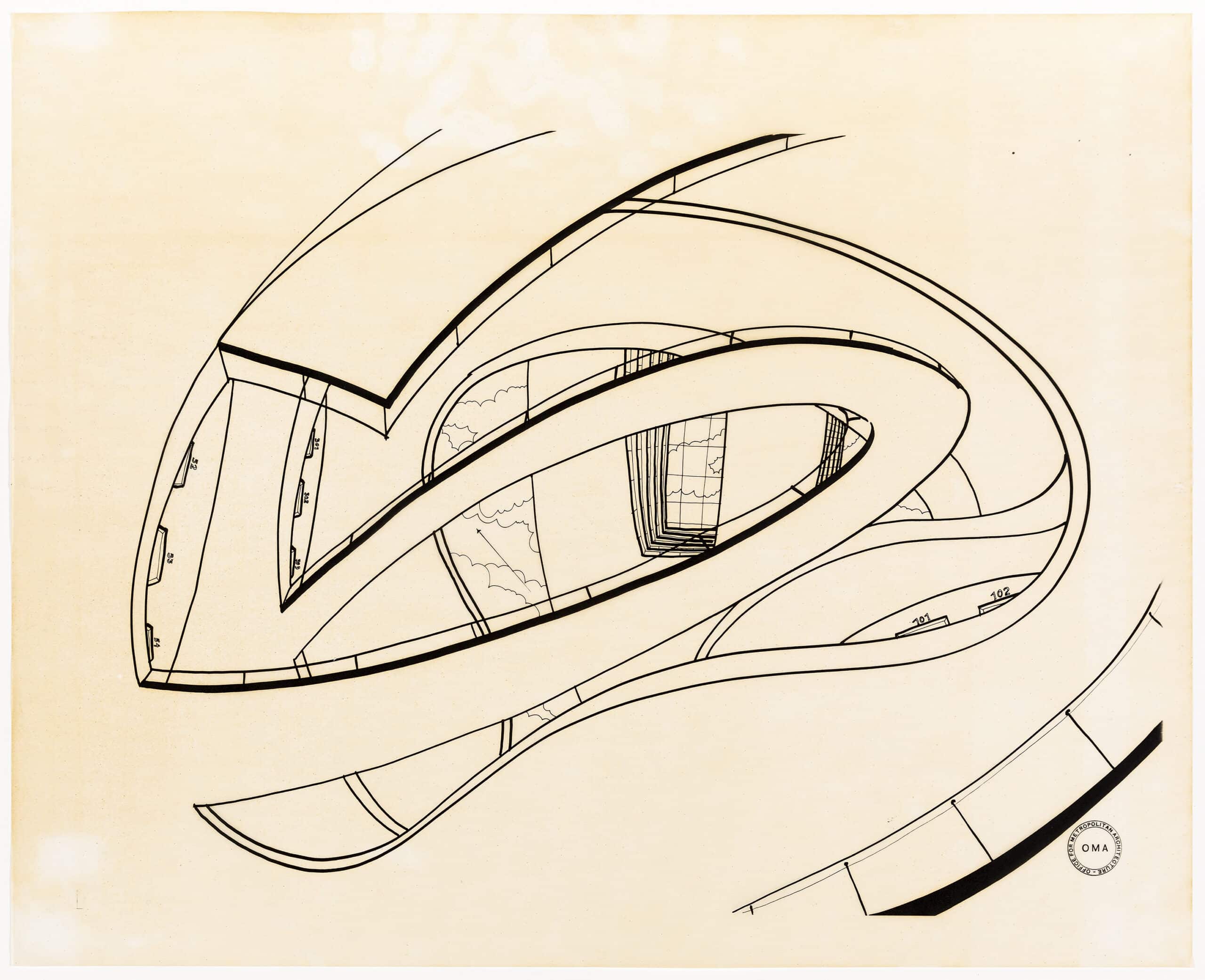

In the exhibition, the curved walls, sometimes with circular cut-outs in them, and the round plinths undulate across the six rooms of our gallery, accompanying the nine chapters that organize the items on view. In the minds of curators, exhibitions are like books that occupy space, where the logic between illustrations and text is inverted. In an exhibition objects and works of art create the narrative, and captions or explanatory wall-texts are in support. That is why in L’architecture des réalités mises en scene (re)construire Disney there are chapters. You don’t have to follow them in order, the convex or concave side of the curves makes one easily lose any linear sequence. Chapters are ‘Creative Beginnings,’ ‘Appropriating Inspiration,’ ‘Disney during WWII’—when the company on the brink of bankruptcy was saved by producing propaganda movies, ‘Disneyland, from Map to System,’ ‘Cultured Nature,’ ‘Expansion as a Model,’ ‘Val d’Europe, Nouvelle Ville,’ ‘Perpetual Systems’ and ‘Virtual Disney Worlding.’ The chapter on Disneyland Paris, the only European park inaugurated in Marne-la-Vallée in 1992 is an addition to the first iteration of the exhibition that was on view at the New Institute in Rotterdam in 2021-2022. It presents early designs—never implemented—by Aldo Rossi, Frank Gehry, Venturi Scott Brown and OMA. It showcases the bland historicist neighbourhoods that have sprouted around the site, where 17.000 persons work: one can argue that New Urbanism is entirely derivative from Disney residential operations, such as Celebration, the gated community in Florida.

It sardonically highlights the gift that Michael Eisner, the legendary CEO, offered to the then president of France, Jacques Chirac when the deal was signed, an original celluloid frame of the sorceress gifting the poisoned apple to Snow-White. This and other seducing objects—the model of the futuristic house in plastic by Monsanto, one of the main attraction at Disneyland; the breathtaking birds-eye renderings by Carlos Diniz for Disneyworld in Florida; the intricated blueprints of work-flows and organizational charts; the US flag with one less star so as not to have to comply with the official guidelines for its display; early merchandise; numerous artists’ contributions; the cartography of an entire island in the Bahamas, purchased and renamed to become a stop for the Disney cruises result in what feels as a stylish and seductively incongruous garage sale, as if the curator was sharing with the audience her own collection, and perhaps, her personal obsessions.

The explanatory text of ‘Perpetual Systems’ summarizes the objective pursued by the exhibition: to elucidate the methodology of the company where movies, places and goods are mobilized to impact us. ‘The core of the Disney formula can be surmised as follows: the narration and staging of perfect pasts, to produce meaningful change in the present, to inform and mold desires towards the future. This self-perpetuating, cycling of the real and the imaginary operates through the recursive feedback between fictive media productions, and tangible consumer goods.’ Recursive feedback, as with all the pictures of Walt, retouched ‘à la soviet’ to cancel the cigarette in his fingers, ultimately the cause of the lung cancer that killed him in 1966, aged 65.

Open for business until January 2025.

Fabrizio Gallanti is a curator and architect with experience in architectural design, education, publications and exhibitions. He is the director of arc en rêve – centre d’architecture in Bordeaux (2021).

The curator of the L’architecture des réalités mises en scene: (re)construire Disney exhibition, Saskia van Strien, wrote the piece Disney: The Architecture of Staged Realities for Drawing Matter, focusing on the fascinating Disney blueprint from the DM collection included in her exhibition The Architecture of Staged Realities.

– Peter Blake