Child’s Play: Adolfo Natalini’s ‘Disegni Per Bambini’

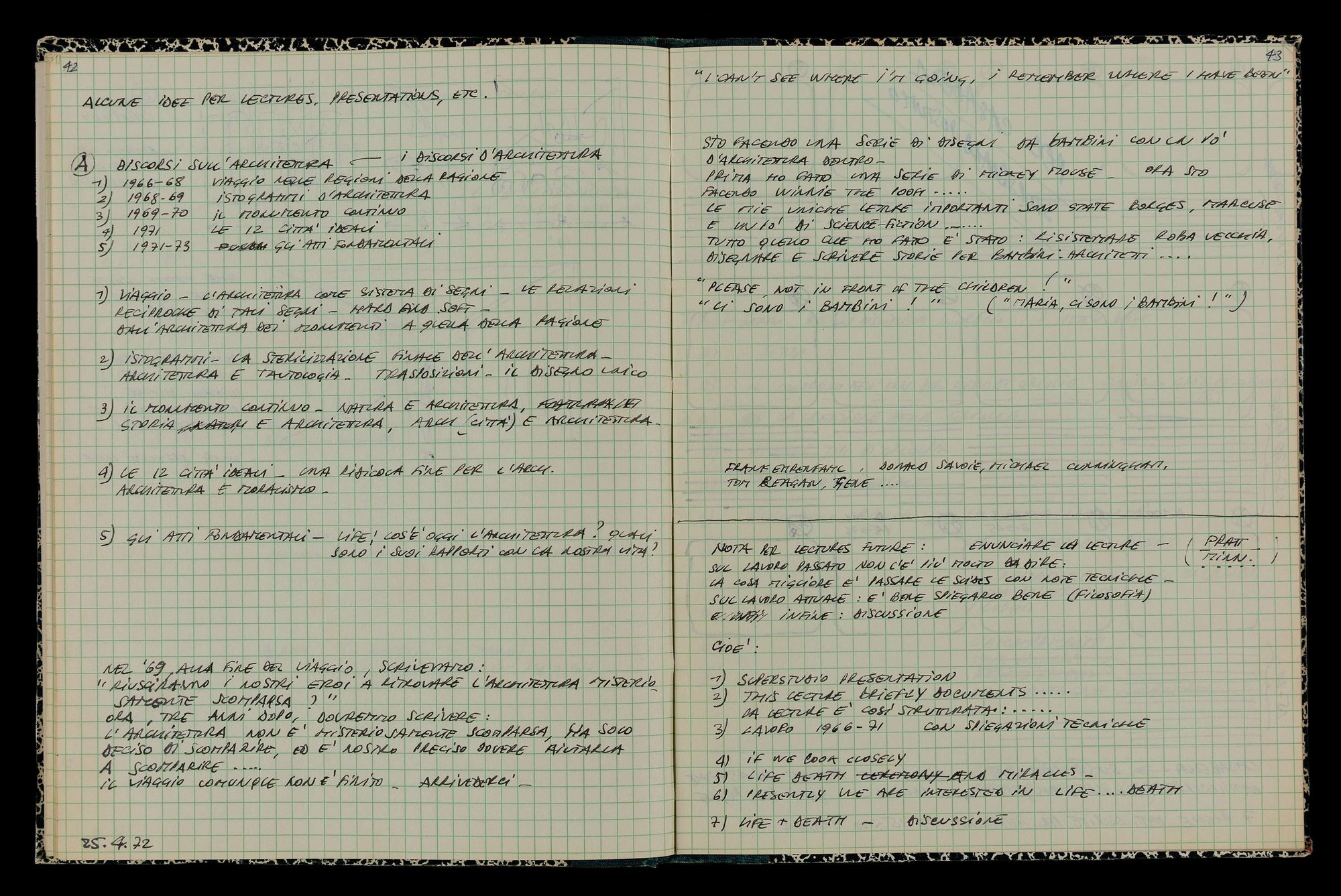

In 1972 Adolfo Natalini spent a few months in the United States. The main event of his visit was the seminal exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape in New York MoMA (May 26 – September 11, 1972). Nevertheless, Natalini spent these months not only working on perhaps the most existential project of Superstudio, The Fundamental Acts, but also curating and re-curating his own and Superstudio’s work through a series of talks and exhibitions. These months’ thoughts and activities are largely recorded and explored in his Notebook No. 17, appropriately carrying the specific title Quaderno Americano (the American Notebook). The notebook presents a series of notes and ideas for lectures, exhibition layouts, storyboards and studies for imaginary landscapes that, true to Superstudio’s origins, explore the ‘regions of reason’ and fantasy, or rather the regions that emerge between reason and fantasy. These varying forms of texts and media are common occurrences in Natalini’s notebooks; nevertheless, in the Quaderno Americano they take on a different, perhaps ‘American’ turn when ‘a friendly little guy’ (as his creator used to call him), Walt Disney’s renowned cartoon character Mickey Mouse, turns up all of a sudden.

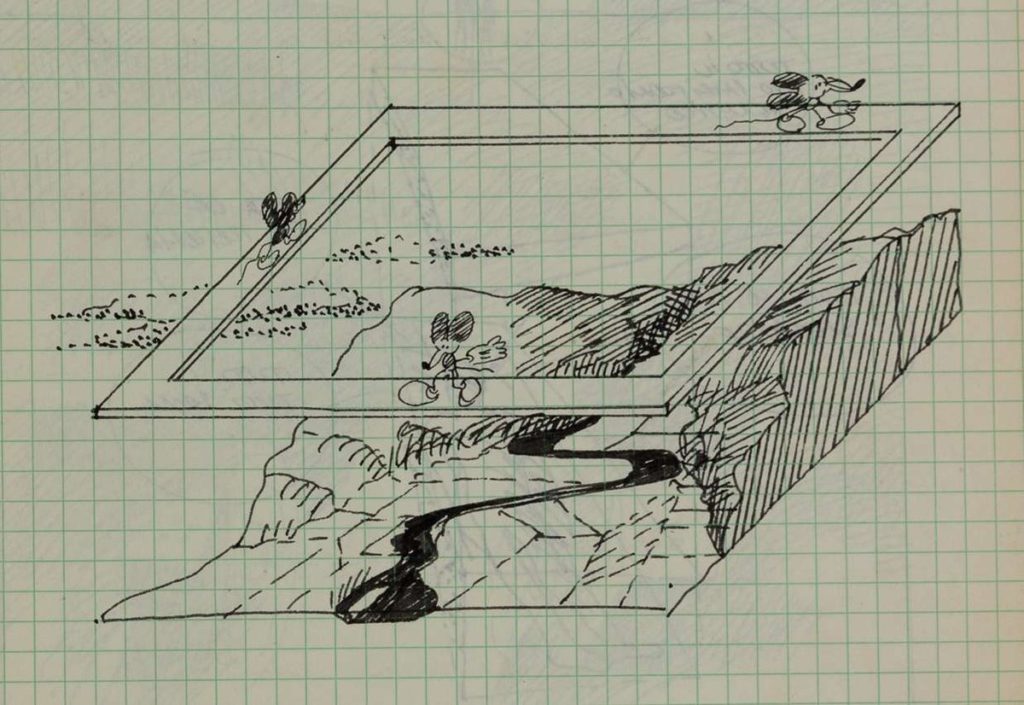

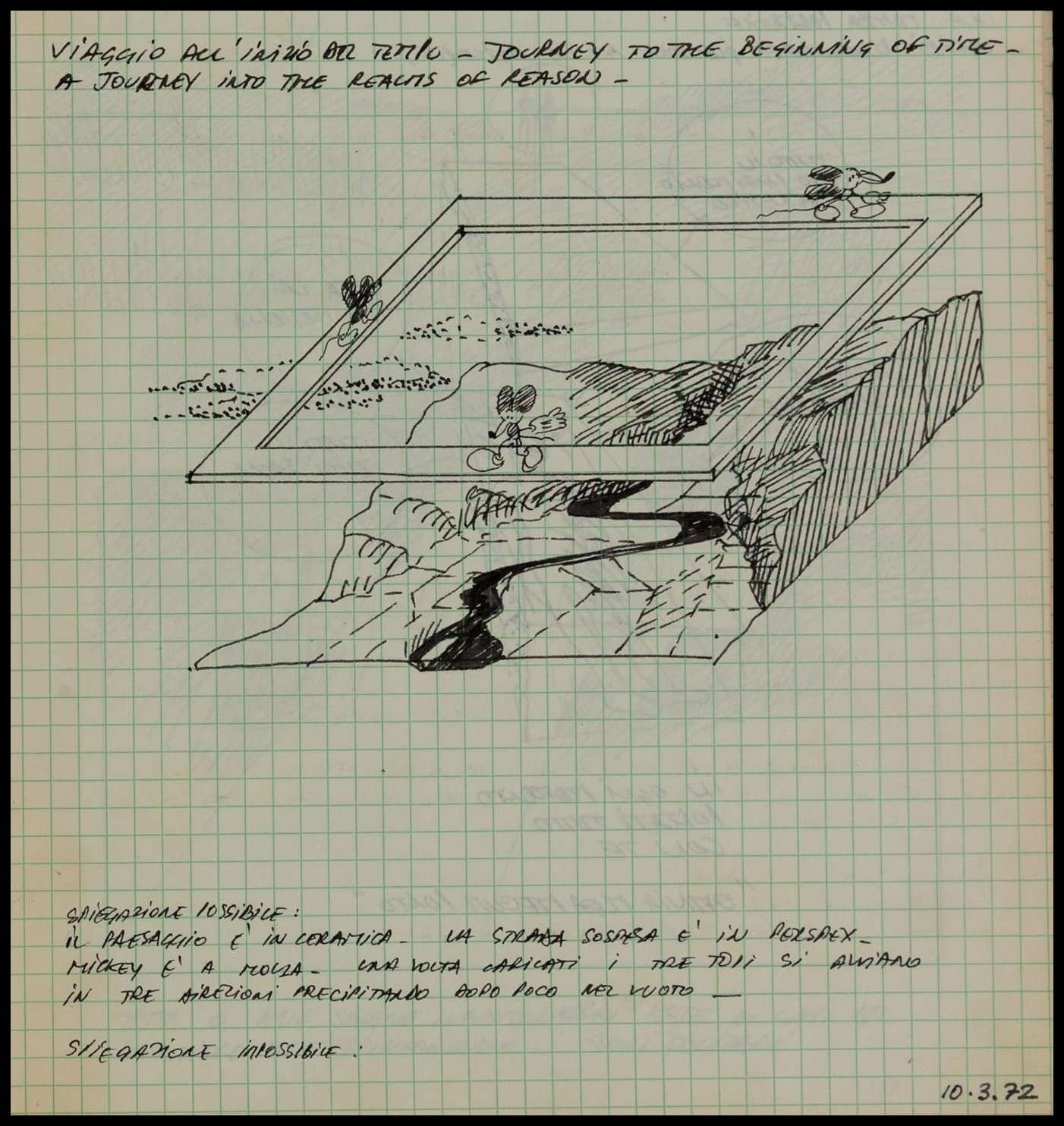

He appears in the very first pages of the notebook following a sketch of thoughts on a kind of Truman Show-type project. Una Vita Intera (An Entire Life) questions the boundaries between real life and representation, proposing the real-time recording of a man’s life from the moment of birth until his death. Immediately following this rehearsal of a project, Mickey circles and scouts a landscape seemingly pulled out from Supersurface (1972).

THIS SELF-PORTRAIT IS MY ARCHITECTURE.

THIS ARCHITECTURE IS MY SELF-PORTRAIT IS THIS ARCHITECTURE IS MY SELF-PORTRAIT IS THIS ARCHITECTURE IS MY SELF…[Quaderno Americano, p. 3 (10.3.1972)]

Natalini offers a ‘possible explanation’ for the realisation of this sketch where Mickey for the first time inhabits a Superstudio landscape across three dimensions, at the same time introducing himself as a third dimension in the nature vs. architecture dualism that has driven Superstudio’s inquiry from the outset of their explorations.

POSSIBLE EXPLANATION:

THE LANDSCAPE IS [DONE] IN CERAMIC. THE SUSPENDED PASSAGE IS IN PERSPEX.

MICKEY IS A CLOCKWORK. ONCE CHARGED THE THREE MICE WILL BE LAUNCHED INTO THREE DIRECTIONS FALLING LITTLE BY LITTLE IN TO THE VOID__

In both the Voyage in the Realms of Reason (1966) and The Continuous Monument (1969) storylines, the opposition between nature and architecture has posed as the backbone of the question of a new architectural sensibility.

Above these two, and in the light of the extreme conjunction of ‘project’ and existence of the Vita Intera (foreshadowing the Fundamental Acts storyboard that follows) Mickey appears as a shadow upturning and challenging the phenomenal balance that the previous Superstudio projects explored. This small fictional creature, a symbol in American – and by now global – culture of the eternal child, adds on top of this universal dualism between ‘mother nature’ and the ‘disciplining’ of architecture the dimension of fantasy as an expression of desire.

The human subject has been present in Superstudio’s preceding works but perhaps most particularly in Supersurface: An alternative Model for Life on the Earth, which they presented in the aforementioned MoMA exhibition. But even before that, it is there in the conventions of reason and geometry, or as the simultaneous oppressed and oppressor of nature within the monumental. However, the point of tension that these two pages mark, can be considered as bringing to the centre-stage of Natalini’s inquiry the human subject as the architect rather than user of architecture by questioning the boundaries between reality and representation, between the ‘natural’ and the ‘constructed’, and acknowledging the mis-en-abyme relation between the architect’s creative desire and the tools that he employs: the fundamental real and the constructed architectural. As the inscription at the top of the page states: ‘This self-portrait is my architecture. This architecture is my self-portrait is an architecture is…’

A twentieth-century iteration of the eternal child archetype, the puer aeternus, Mickey stands for innocence as well as mischief. Originally inspired by characters such as those portrayed by actor Charlie Chaplin and nineteenth-century American writer Horatio Alger, he represented the naivety of the poor but honest antihero who eventually prevails over all hardship. [1] Like a child, however, he is at the same time resourceful and restless. In the American context of the Quaderno Americano, he is also a symbol of pop culture as the result of commodification and consumerism. At once a rebel and a commodity, Mickey Mouse represents the utopia of the American-come-universal Dream on all levels: the innocence and playfulness of the eternal child as well as the commodification of the (children’s) dreams. [2]

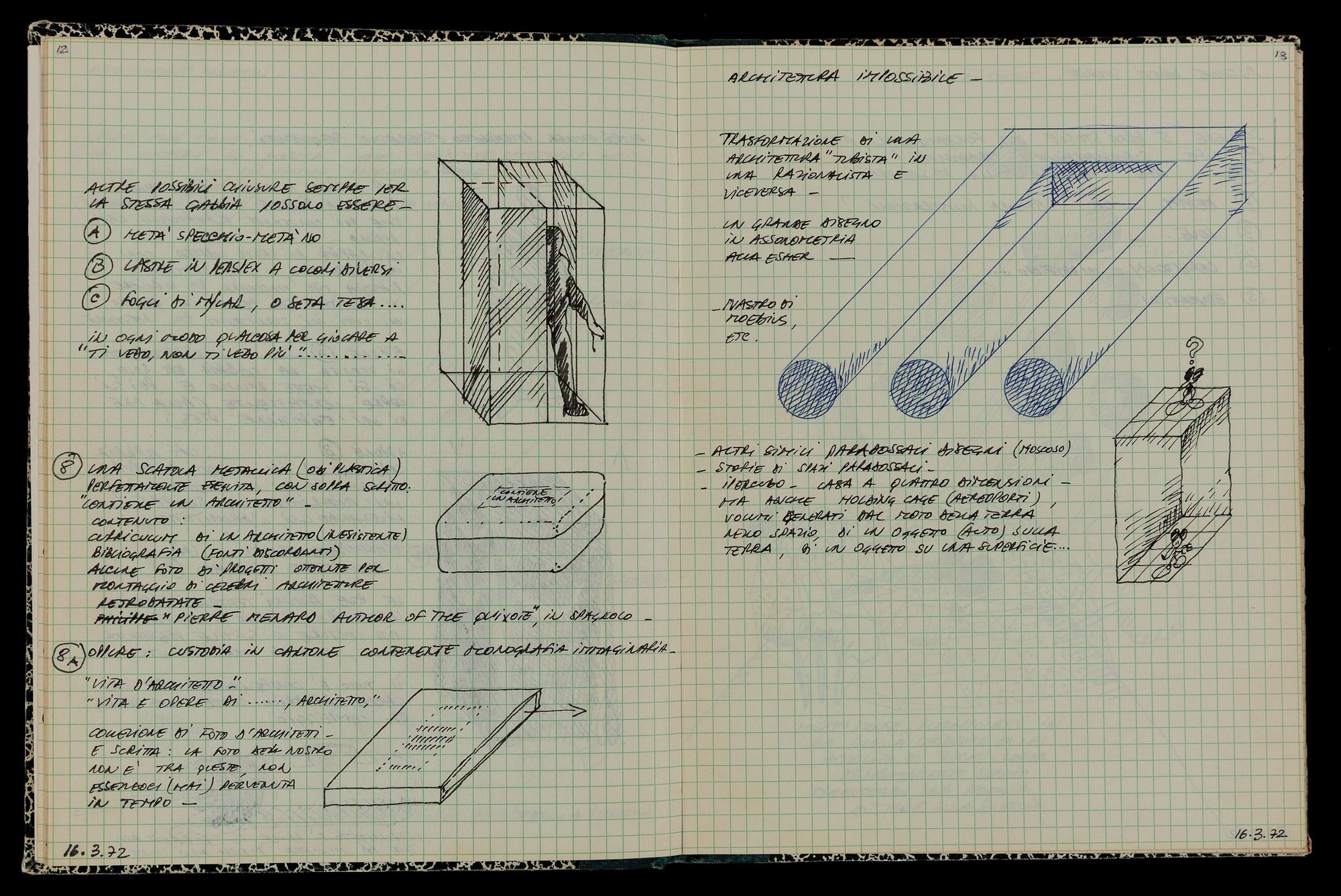

On one hand Mickey presents himself as an ‘architecture’; a spatial and cultural construct. On the other hand, his dark figure becomes the ‘keyhole’ that allows us to peek into a reflective architecture which no longer reflects the contrast between nature and architecture, but rather the ‘likeness’ between the architect and his work. There is therefore an existential commentary that one may discover in these sketches. Drawing emerges as a field of playful exploration, where the representational play of the architect is uncovered for what it is (with or without Mickey): a space of representation that operates on a condition of both innocence and mischief, on the conjunction of personal fantasies and geometric conventions. Appropriately, Mickey’s next ‘cameo’ presents him entrapped within and without a gridded box, across a page that explores a series of containers – and consequently definitions – of the architect.

OTHER POSSIBLE ENCLOSURES FOR THE SAME CAGE COULD BE

A – HALF A MIRROR-HALF NOT

B – PERSPEX PLATES IN DIFFERENT COLOURS

C – MYLAR SHEETS, OR TENSED SILK

IN EVERY WAY SOMETHING THAT WILL PLAY WITH

“NOW I SEE YOU, NOW I DON’T”…8 – A METALLIC BOX (OR PLASTIC)

PERFECTLY EXECUTED, WITH WRITTEN ON IT (SIC)

“CONTAINS AN ARCHITECT”

CONTENT:

THE CV OF AN ARCHITECT (NON-EXISTENT)

A BIBLIOGRAPHY (DISCORDANT FONTS)

SOME PHOTOS OF PROJECTS DERIVED FROM

THE MONTAGE OF FAMOUS ARCHITECTURES

BACKDATED —“PIERRE MENARD AUTHOR OF THE QUIXOTE”, IN SPANISH

8A – ALTERNATIVELY: A CASE MADE OF CARDBOARD CONTAINING AN IMAGINARY MONOGRAPH

“LIFE OF THE ARCHITECT”

“LIFE AND WORKS OF ……, ARCHITECT”A COLLECTION OF PHOTOS OF ARCHITECTS

WITH THE INSCRIPTION: THE PHOTO OF OUR [ARCHITECT]

IS NOT BETWEEN THOSE, IT WILL (NEVER) BE THERE IN TIME–[Quaderno Americano, p. 12 (16.3.1972)]

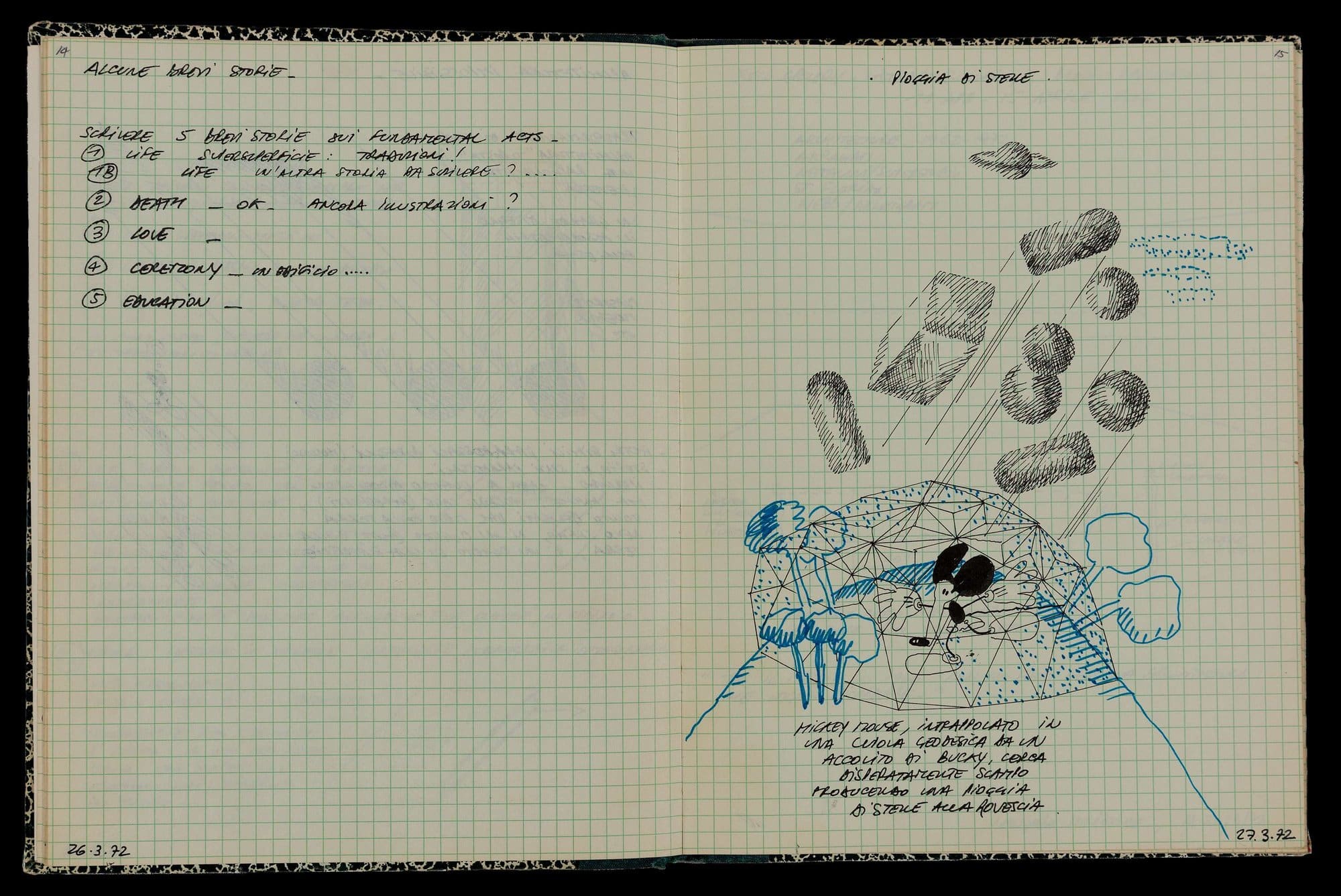

A few days later (27.03.72), Mickey is trapped again in a different setting, echoing the Arizona Crater project drawings for an exhibition of the same period in Providence:

. STAR SHOWER .

MICKEY MOUSE, TRAPPED IN

A GEODESIC DOME BY AN

ACOLYTE OF BUCKY’S [BUCKMINSTER FULLER],

DESPERATELY SEEKS ESCAPE CAUSING THE BREAK OUT OF

A STAR SHOWER

In the Quaderno Americano the Mickey sketches do not emerge from a single project. Rather, they weave around studies for the various projects that occupied Natalini’s mind at the time, almost as a kind of escape for the architect himself. They are never a project in themselves but a playful reflection on the very idea of being an architect, disguised as a running commentary on the projects explored. Eventually Natalini somewhat more explicitly reveals the significance of the sketches: architects are like children.

“I CAN’T SEE WHERE I’M GOING. I REMEMBER WHERE I HAVE BEEN”

I HAVE BEEN DOING A SERIES OF CHILDREN’S DRAWINGS WITH A LITTLE BIT OF ARCHITECTURE INSIDE _

FIRST I DID A SERIES WITH MICKEY MOUSE _ NOW I AM DOING ONE WITH WINNIE THE POOH…..

MY ONLY IMPORTANT READINGS HAVE BEEN BORGES, MARCUSE

AND A LITTLE BIT OF SCIENCE FICTION……..

ALL I HAVE EVER DONE IS: REPOSITION OLD STUFF,

DRAWING AND WRITING STORIES FOR CHILDREN: ARCHITECTS ….

“PLEASE NOT IN FRONT OF THE CHILDREN !”

“CI SONO I BAMBINI !” (“MARIA, CI SONO I BAMBINI !”)

FRANK EHRENFAHL , DONALD SAVOIE, MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM,

TOM REAGAN, GENE ….

So what is it exactly that confirms the ‘childishness’ of the architect? Is it the naivety of believing in the imaginary worlds their drawings uncover, or the very cunning involved in the act of crafting these utopias? In essence, and to validate the accuracy of the simile, it is about both: the architect is a character of oppositions just like Mickey Mouse. This is a case so often evident in Superstudio’s work, negotiating architecture and nature, geometry and feeling, and in Natalini’s case: pop-art painting and architectural drawing.

This double nature is nowhere made clearer than in the act of drawing, considered in turn as a ‘child’s play’. Georges Didi-Huberman proposes play as a ‘theory of knowledge’ that takes place through operations of disconnection and composition: the smashing and reassembling of the toy is considered as a process of conquering and reordering knowledge [3]. It is in representation then that the re-territorialization, the ‘repositioning of old stuff’, takes place through a process of destruction and (re)composition. The play of the re-organization of the real through the fantastic in architecture is only possible due to the doubling of drawing as a disciplining convention grounded within reason and a field of invention animated by imagination. This process of ‘connaissance’ through the image of representation inevitably extends into the architect: the toy he plays with is not purely external to his subjectivity. Rather, it relies in his own participation. Similarly to Mickey’s adventures in the Quaderno Americano, Natalini’s ‘adventures’ in the US seem to have involved a process of reflection not only on architecture as discipline, through new emerging projects, but also on his own standing as an architect reflecting on the American context. Like Mickey, he too inhabits the Superstudio ‘landscape’ through the repositioning and re-presentation of his ‘older’ architecture for talks and exhibitions.

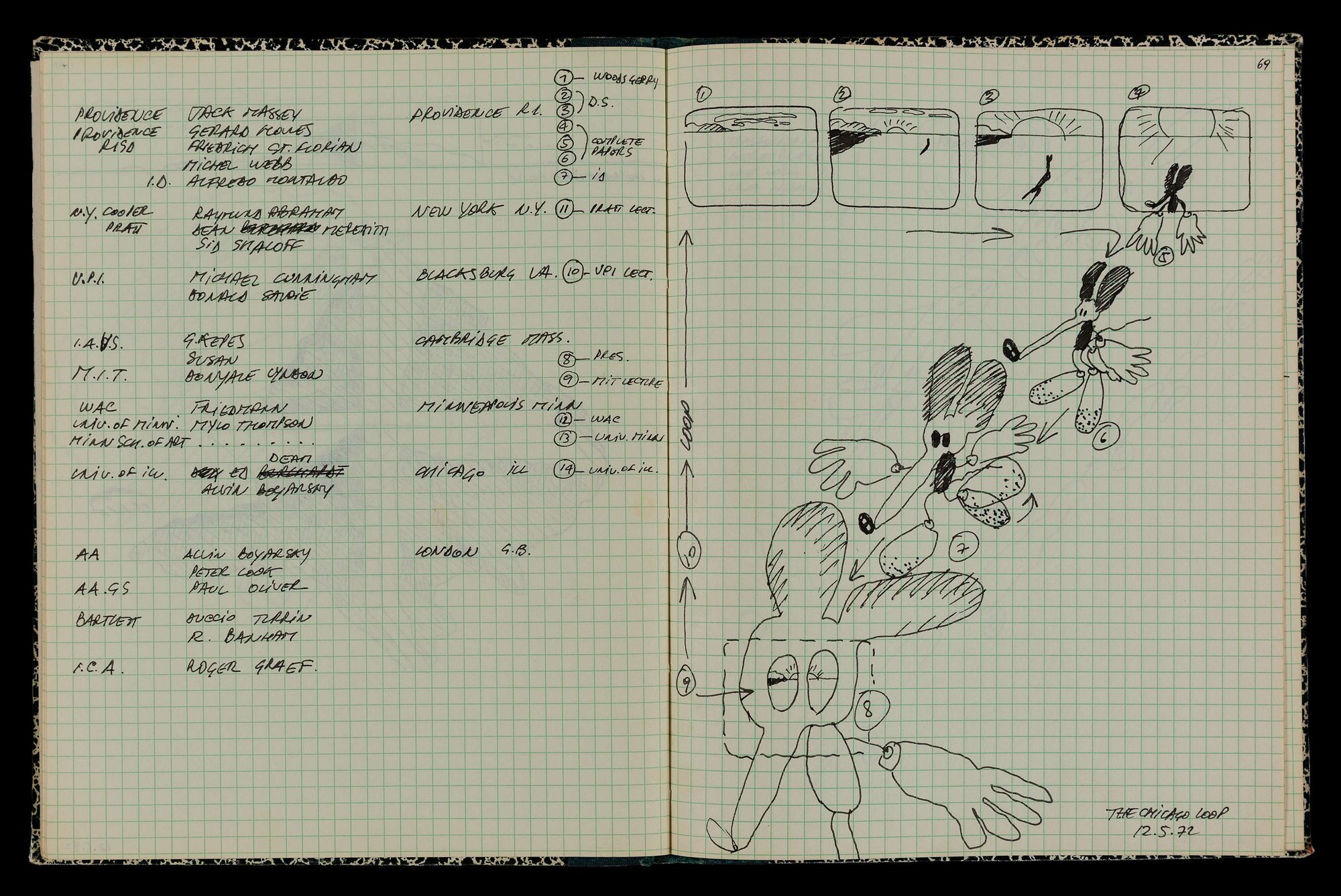

The Chicago Loop: Mickey, the eternal child or the ‘eternal architect’, is depicted actively negotiating this space of representation as the liminal condition between not only reality and invention, but also between the self and the other. He emerges from a vast, empty landscape, gradually getting closer. He eventually escapes the frame of the representation, only to enter it again, alternating between the positions of the spectacle and the spectator.

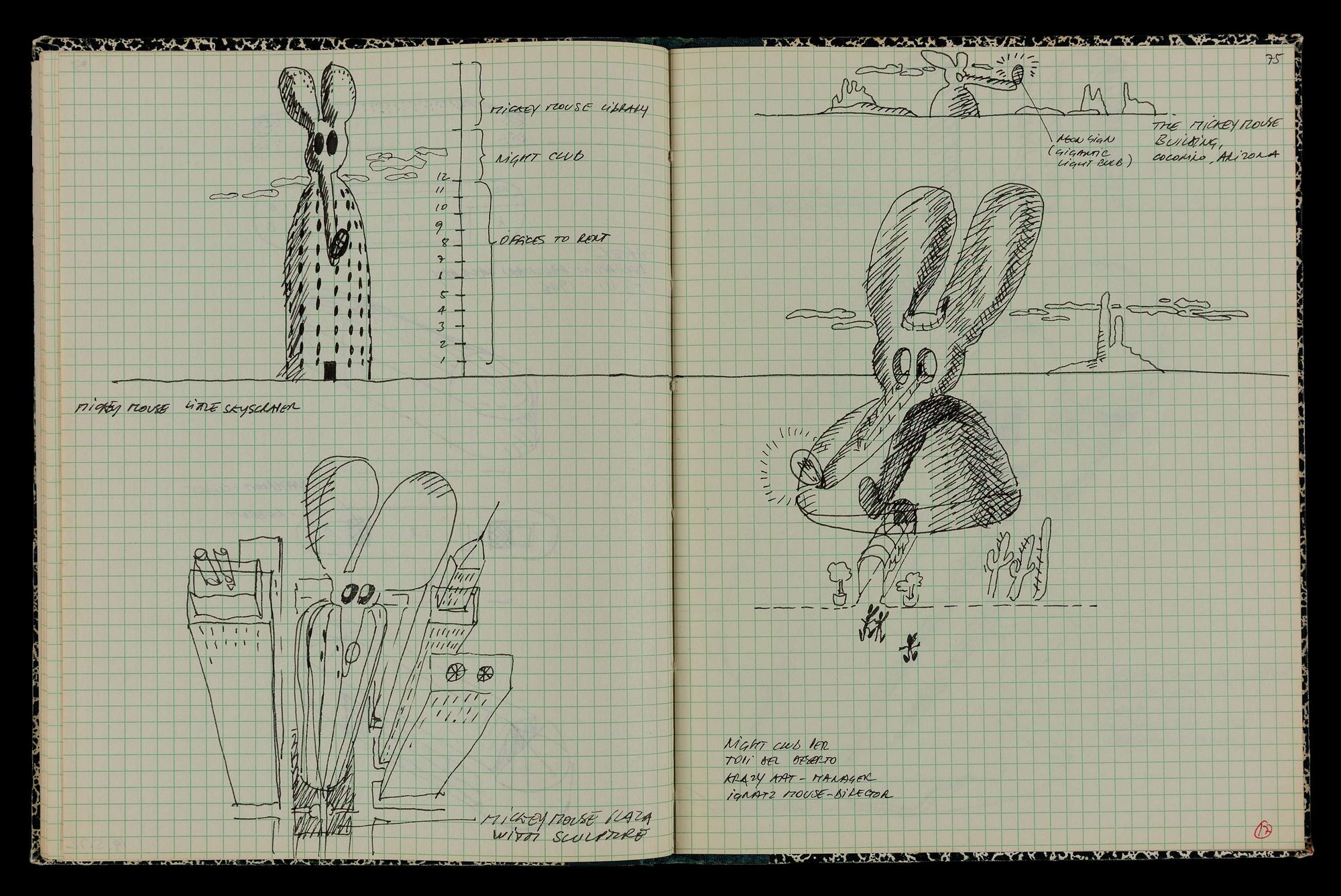

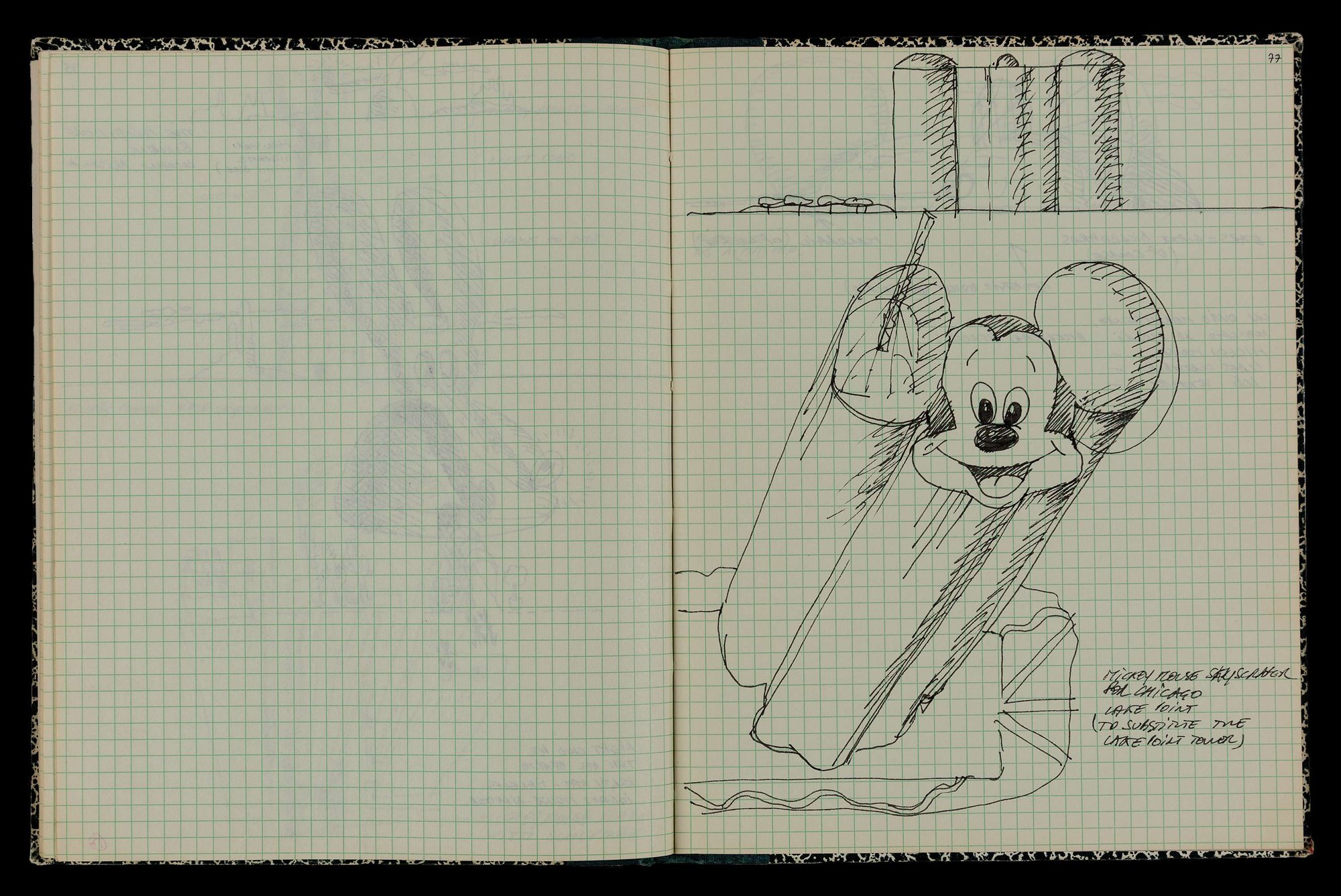

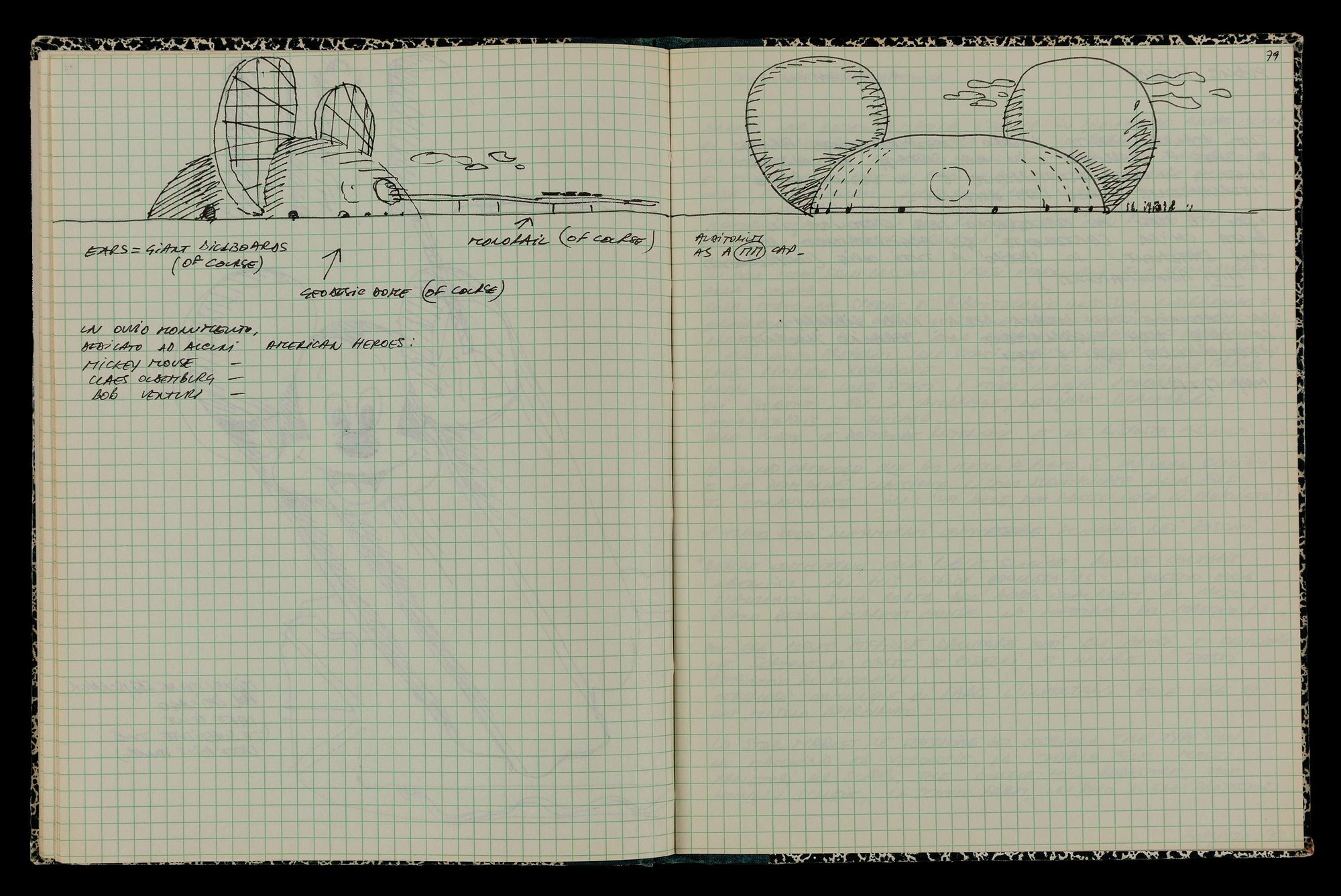

Pages 74–79: Studies for a series of ‘Mickey-morphic’ architectures. Two versions of a Mickey skyscraper (one particularly proposed to substitude Lake Point Tower in Chicago), a ‘Mickey Mouse Plaza’, a club for the ‘mice of the desert’ in Coconino Arizona, to be managed by Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse, and a Mickey Mouse cap auditorium, as an ‘obvious monument dedicated to a few American heroes’: Mickey Mouse himself, the pop-art sculptor Claes Oldenburg and Robert Venturi – ‘of course’ however, including a geodesic dome. Mickey presents here for Natalini a distillation of American culture in his own (artistic and architectural) interests: from the absurdity of Pop Art, to Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes and Robert Venturi’s discussion of postmodernist iconicity.

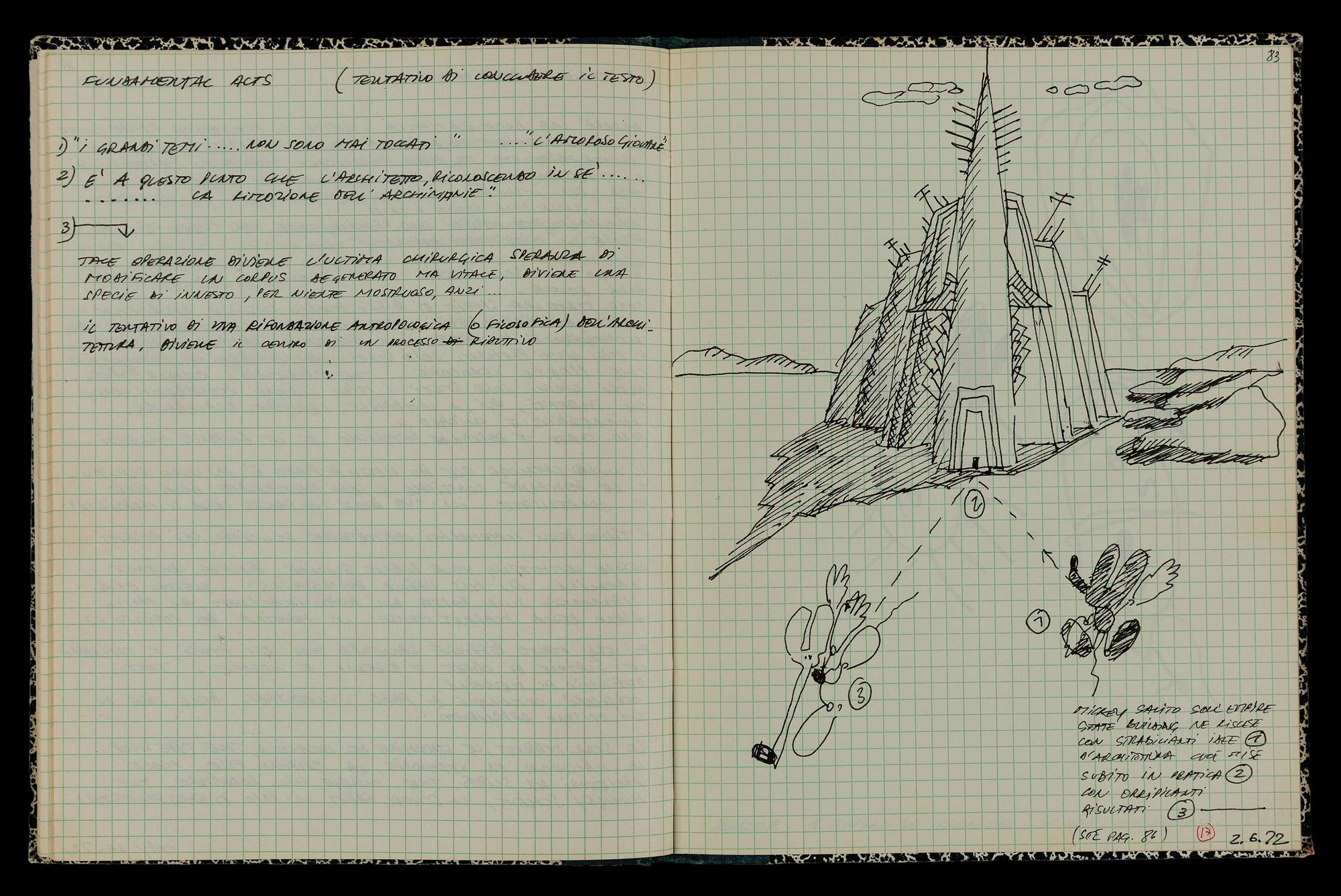

Like all of Superstudio’s work, Natalini’s incarnation of Mickey as the ‘eternal child/architect’ is a creation painted with humorous and ironic shades. He is thus a real antihero: there to be liked and critiqued, as is architecture itself – and, by extension, the architect – in Superstudio’s work. Mickey’s adventures in Notebook No. 17 are therefore concluded in the most ‘Superstudio’ way. After pages and pages of studying the Fundamental Acts storyboards, Mickey reappears to ‘put to practice’ the ‘amazing’, yet borderline ‘horrific’ ideas that he came up with in the United States, which are summarised by the overlooking presence of the Empire State Building. In doing so, this animated hero too finds his way into the filmic narrative device of the storyboard and deeper into Superstudio’s fantastic realms of reason and ‘reasonable absurdity’:

GOING UP THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING

MICKEY COMES UP WITH AMAZING IDEAS (1)

OF ARCHITECTURE THAT HE PUTS

IMMEDIATELY IN PRACTICE (2)

WITH HORRIFIC

RESULTS (3) _

(SEE PAGE 86)

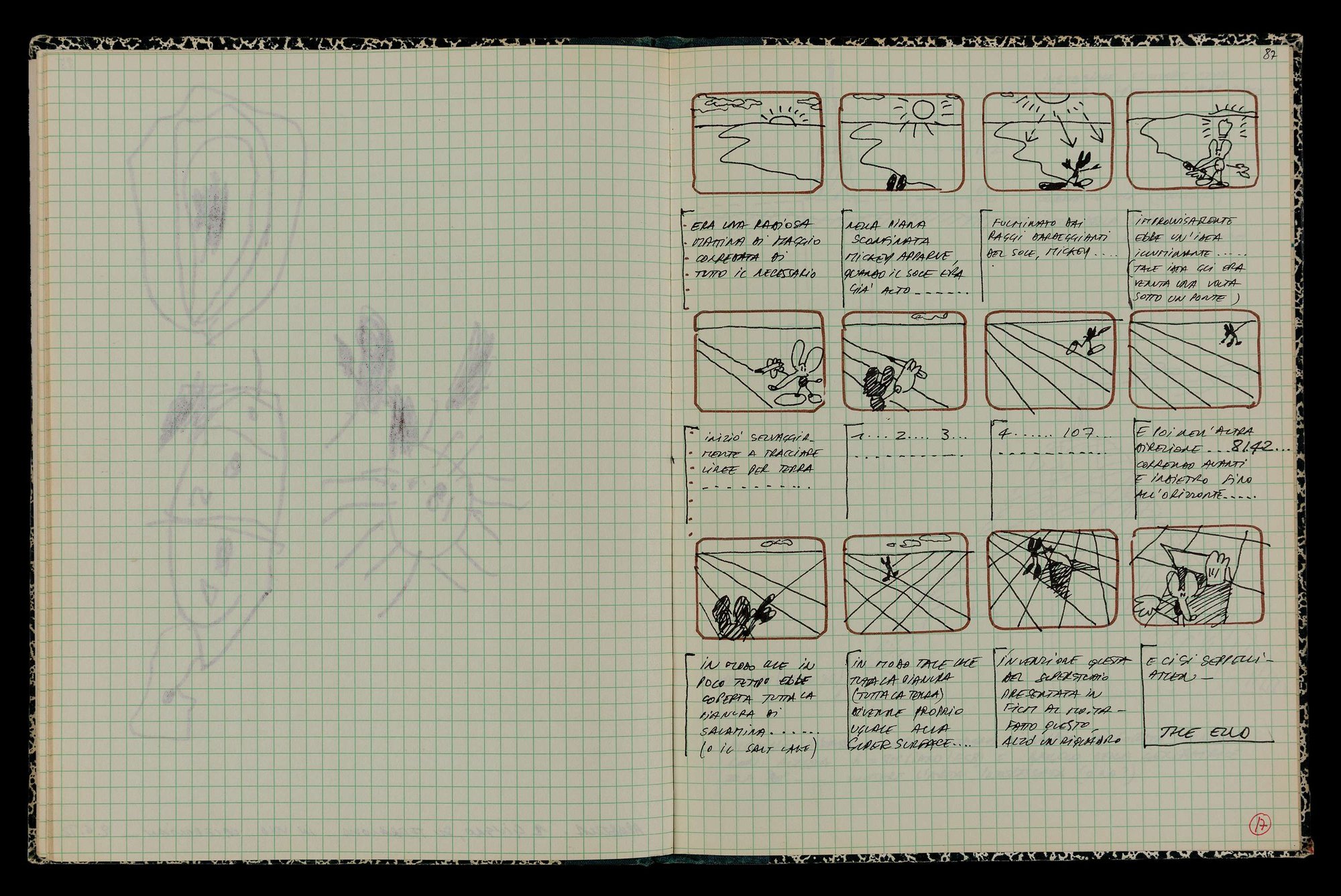

IT WAS A RADIANT MAY MORNING ACCOMPANIED BY EVERYTHING NECESSARY

MICKEY APPEARED IN THE QUIET OPEN WHEN THE SUN WAS ALREADY HIGH……

STRUCK BY THE DARTING SUN RAYS, MICKEY…

SUDDENLY HAD AN ILLUMINATING IDEA…..

(ONE TIME HE HAD HAD SUCH AN IDEA UNDER A BRIDGE)HE STARTED FRANTICALLY TRACING LINES ON THE LAND

……….1… 2… 3…

…………..4…… 107…

…………..AND THEN IN THE OTHER DIRECTION… 8142…

RUNNING BACK AND FORTH ALL THE WAY TO THE HORIZONIN A WAY THAT SOON HE HAD COVERED ALL OF THE PLAIN OF SALAMINA (OR SALT LAKE)

IN SUCH A WAY THAT THE WHOLE PLANE (THE WHOLE LAND) BECAME EXACTLY THE SAME AS THE SUPERSURFACE

THAT INVENTION BY SUPERSTUDIO THAT HAD BEEN PRESENTED IN A FILM IN MoMA.

HAVING DONE THAT HE LIFTED A SQUAREAND THERE HE BURIED HIMSELF –

AMEN –THE END

Notes

- Bruce David Forbes (2003), ‘Mickey Mouse as Icon: Taking Popular Culture Seriously’, Word & World 23(3), pp. 242–252.

- Henry Giroux (1999), ‘The Mouse That Roared: Disney and the End of Innocence’, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Georges Didi-Huberman (2000), ‘Connaissance par le Kaléidoscope: Morale du joujou et dialectique de l’image selon Walter Benjamin’, Etudes Photographiques 7, https://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/204?lang=en. Accessed 15 August 2017.