Materia 2: Corrugated Iron

This text is the second in a series by Gordon Shrigley titled ‘Materia’ in which the architect meditates on the physical and semiotic nature of a number of everyday construction products. Forthcoming texts will include thoughts on oxide-red paint, in-situ concrete, fired brick, plate glass and plastic. The first text in the series, on render, can be read here.

First cast then bent, one flute at a time, the corrugated iron panel; a cheap obdurate material, has spread like a ‘pestilence over the country’, [1] leaving in its wake a monstrous legacy, that both seduces and repels in equal measure by folding the horizon of architecture within itself, into one easily transportable moduli.

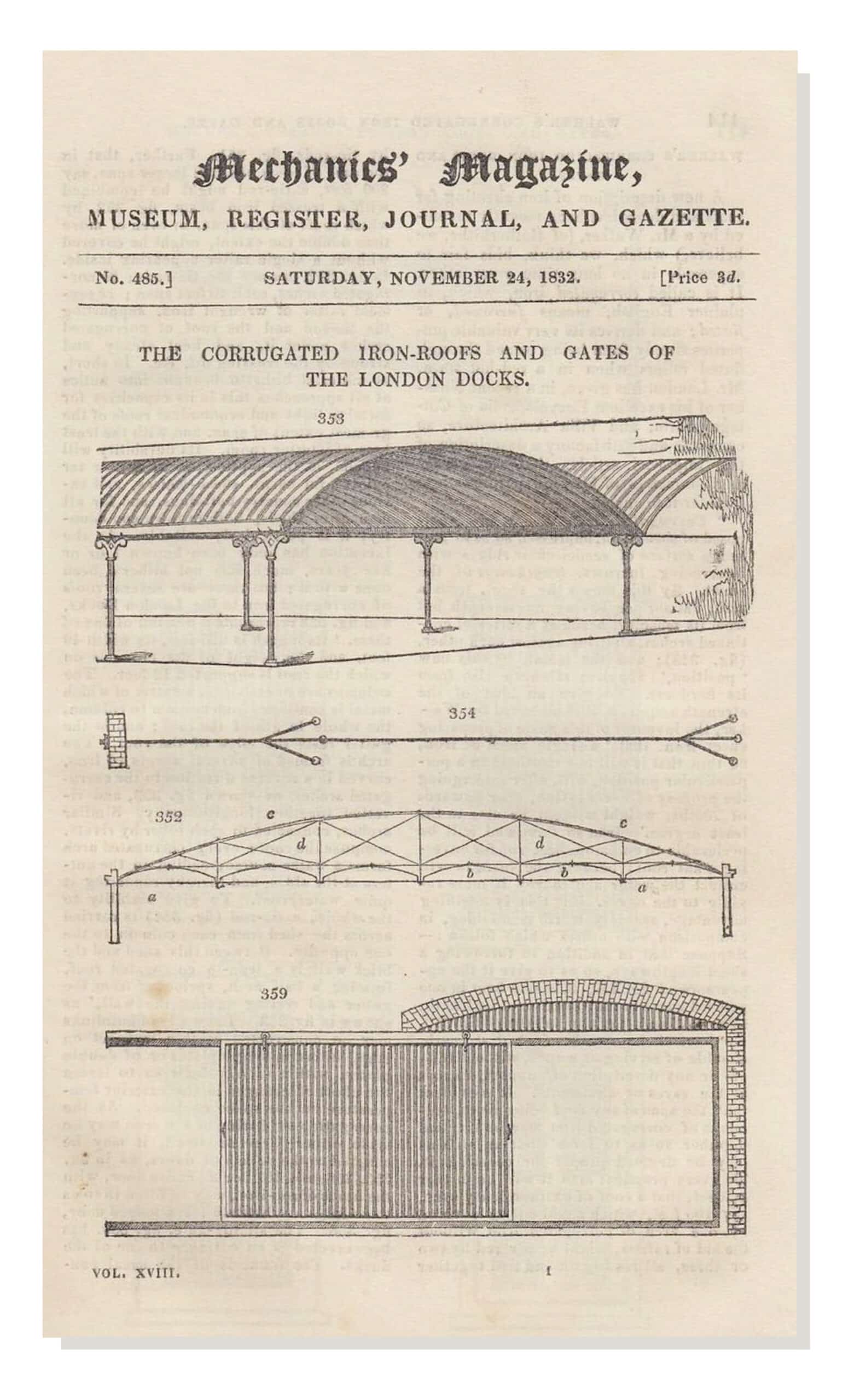

In 1829, Henry Robertson Palmer, then engineer to the London Docks, filed patent number 5786 for: ‘My improvement or improvements in the construction of warehouses, sheds, and other buildings… [consisting of] the application of metallic plates or sheets, in a fluted, indented, or corrugated form, to the purposes, in relation to buildings.’ [2]

The radical simplicity of Palmer’s invention was in discovering that by mechanically pressing down onto an iron sheet to create a series of parallel furrows, the strength of each panel was significantly increased. He further ventured that by curving each panel in the direction of the grooves also improved the rigidity of each panel in two directions too.

Palmer’s first demonstration of the properties afforded by his invention was his design, completed in 1830, for a large open-sided rectangular canopy that, due to its use of curved corrugated sheets, did not require the use of a wood or iron support structure.

The sight of a large, only millimetres-thick roof, effortlessly spanning 12 metres between cast iron columns without any discernible support, was, one can imagine, a sight to behold; as nothing quite as daring as this had ever been seen before and signalled the dawning of the Victorian age of invention.

Palmer’s near-magic structural feat also changed the future of architecture.

From the moment of the invention of the corrugated panel, tectonic culture effectively collapsed into one point, one singularity: the genesis of the panel as archetype as both material and ideational reality. Simply, once the idea of the corrugated iron sheet is realised and the radical implications of a self-supporting pre-fabricated rigid panel is recognised, there is no going back to a time before the panel.

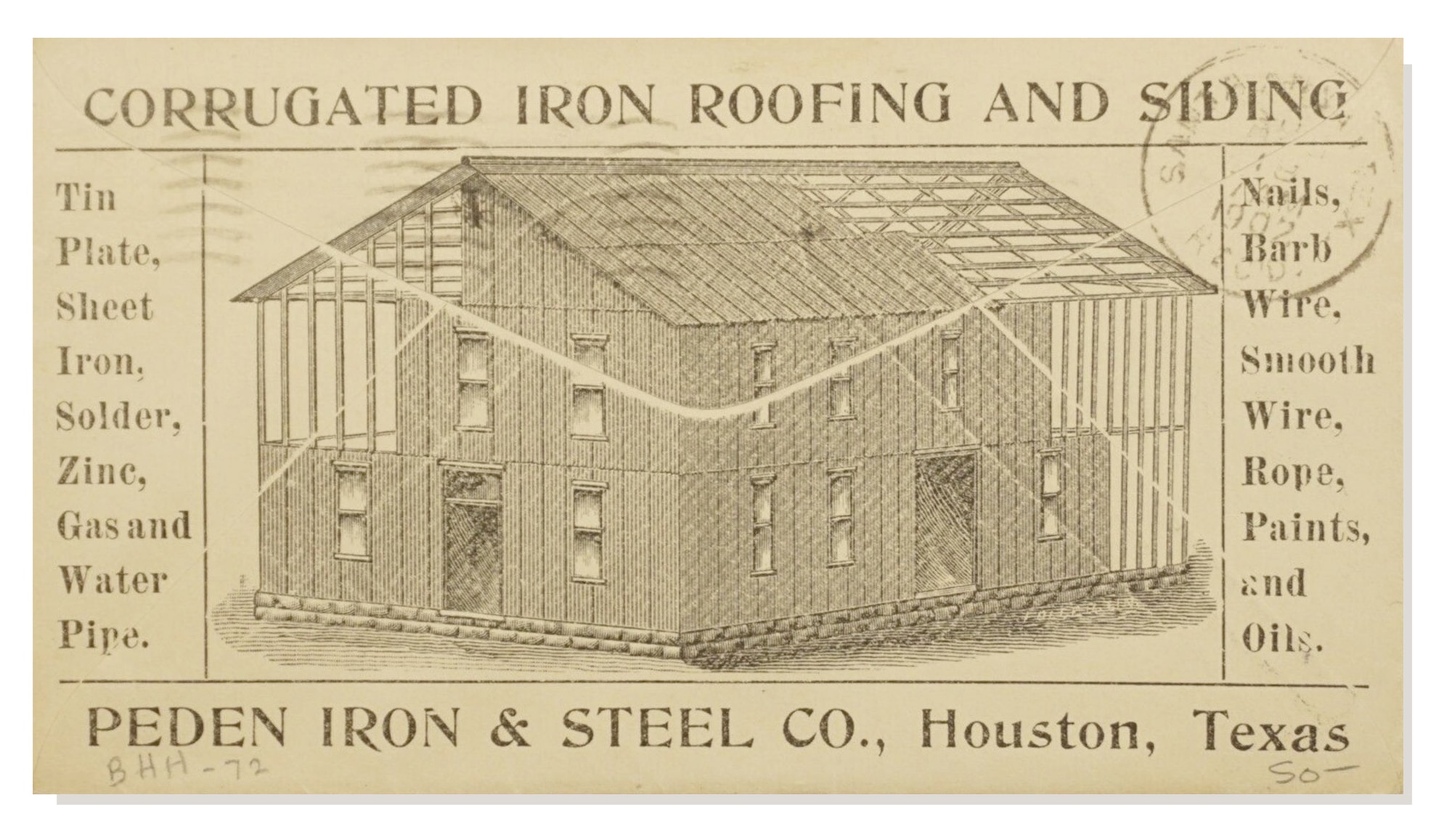

In 1860, Palmer’s patent eventually ran out, allowing neither prayers nor demonstrations to halt the advance of William Morris’s prophesied pestilence. The result was that corrugated panels spread not just throughout the country, but also to the outermost edges of the Empire; corrugated iron provided the perfect rough and ready solution to the urgent need for cheap and quickly constructed space. This form of construction also allowed the newly invigorated entrepreneurial class to bypass the power of the Guild and its coveted traditions of lengthy apprenticeships and hand-made craftsmanship. Anyone with a stout enough constitution and rudimentary carpentry skills could erect a corrugated iron building in relatively short order.

The gauche utility of corrugated iron also distinguished it from the peccadillos of architects of the time and their much-lampooned obsessions with questions of aesthetics and decorum over pragmatic simplicity. Yes, Henry Robertson Palmer was an engineer, a man of substance, fully immersed within the ideology of pragmatic action and hence not weighed down with the seemingly effete flights of fancy of architects and their adherence to the idea of history as rampart.

Furthermore, in line with the much-vaunted ethics of utility of the period, the invention of corrugated iron also reinforced and reproduced materially the aura of Victorian self-sacrifice. Corrugated iron’s inherent crudity of manufacture, its raw pitted finish, first painted and then galvanised, signified a brut sensibility that was unencumbered with any then known notions of machine-made beauty or grace. The sense that corrugated iron sheets represented a no-nonsense anti-aesthetic therefore, provided the ideal material base to project Pax Britannica onto the world.

The Imperial Century: 1815–1914, required the manufacture and mobilisation of a cheap, durable and easy to construct instant space, to house all the jolly good fellows who bravely signed up to administer British commercial interests. It was largely within corrugated bungalows and tin tabernacles that the various field agents of the Empire carefully applied the symbolic capital of English exceptionalism, state violence, famine and faith to subjugate the colonised.

Simply, after the invention of corrugated flat and curved sheets, buildings could be manufactured from lightweight engineered modular parts, easily fixed together wherever and whenever they were needed and then dismantled and moved to another colony.

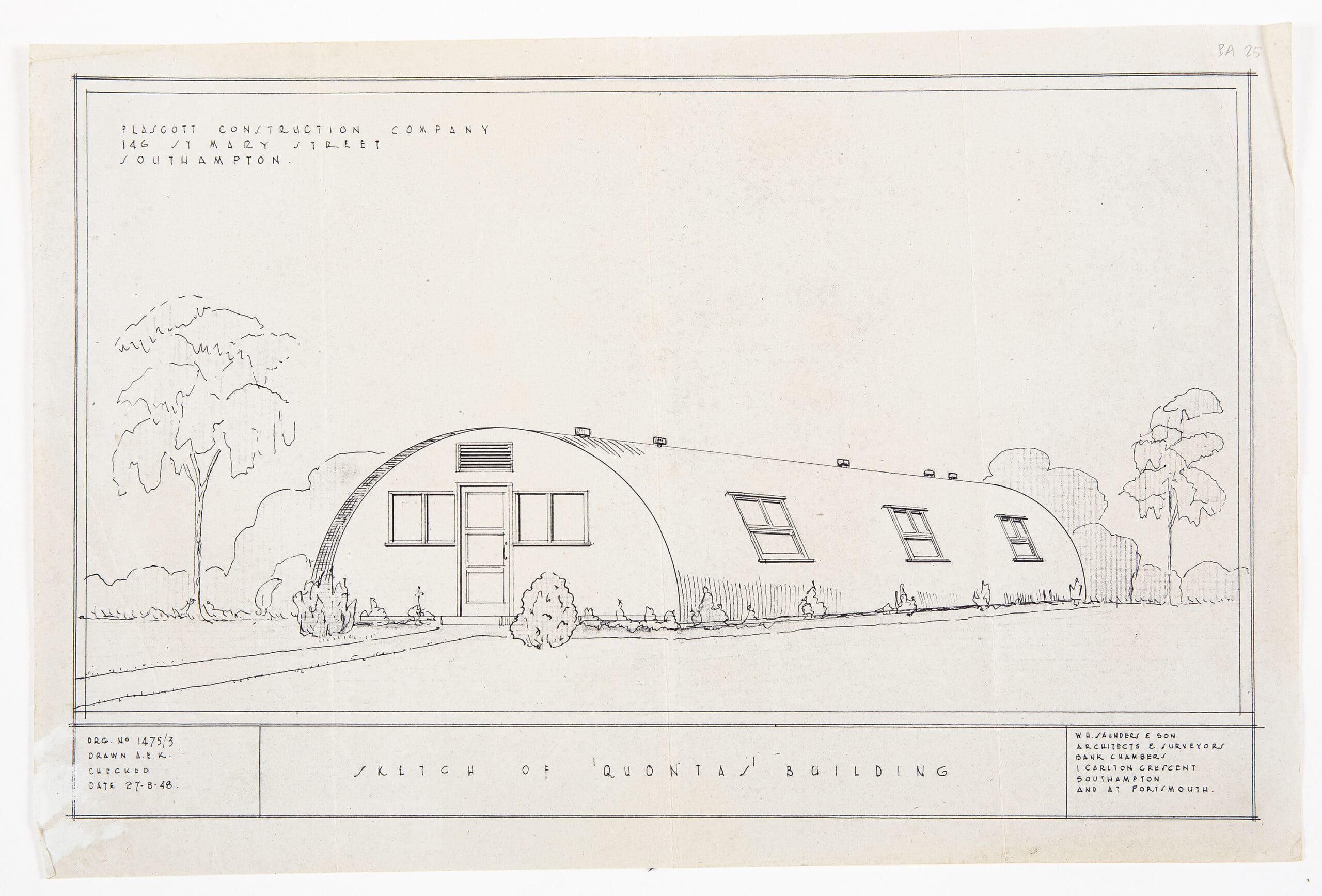

The invention, industrial manufacture and distribution of the corrugated panel established a moment of critical finality within the story of architecture. Once instantiated, the panel as idea became the underlying motive force for tectonic culture, rendering the hitherto sovereign tradition of the post and beam and the piling of one lumpen material upon another as ideationally obsolete. Even though trabeation has never really quite died out, the future, I would contend, from the moment of Palmer’s invention, belongs inexorably to the vocabulary of the Plattenbau. However much pre-fabricated building systems are known by their limitations, they still retain the potential to transform the medieval practices of building culture, into a mode of enquiry that is capable of providing panellised Mil-Spec living machines, on a par with armament and vehicle manufacture, for a variety of on and off-world sorties.

It is difficult to imagine from within our historical perspective the extent to which the first corrugated buildings caused both open-mouthed amazement and well-reasoned fear – considering corrugation’s later ubiquity. For some, corrugated buildings clearly expressed the revolutionary spirit of industrial Capitalism and its promise of the betterment of everyday life. But for other more notable critics, corrugated iron panels and iron buildings generally signified the coming death of architecture, as exemplified by the much-vaunted tectonic traditions associated with heavy quantities of well-honed brick, stone and wood, held together with congealed mud, wooden dowels and gravity.

We can perhaps sense too that the invention and use of corrugated iron panels, which were manufactured on a mass scale during the period 1860–1910, also signalled a moment when the cultural and economic power of the highborn architect was threatened and finally displaced by the coalescing interests of the emergent profession of the middle-class engineer and the buccaneers of industry and colonial adventure, who from this conjuncture, have been bound together in their twin desires to reshape the world in their own inevitably deracinated image.

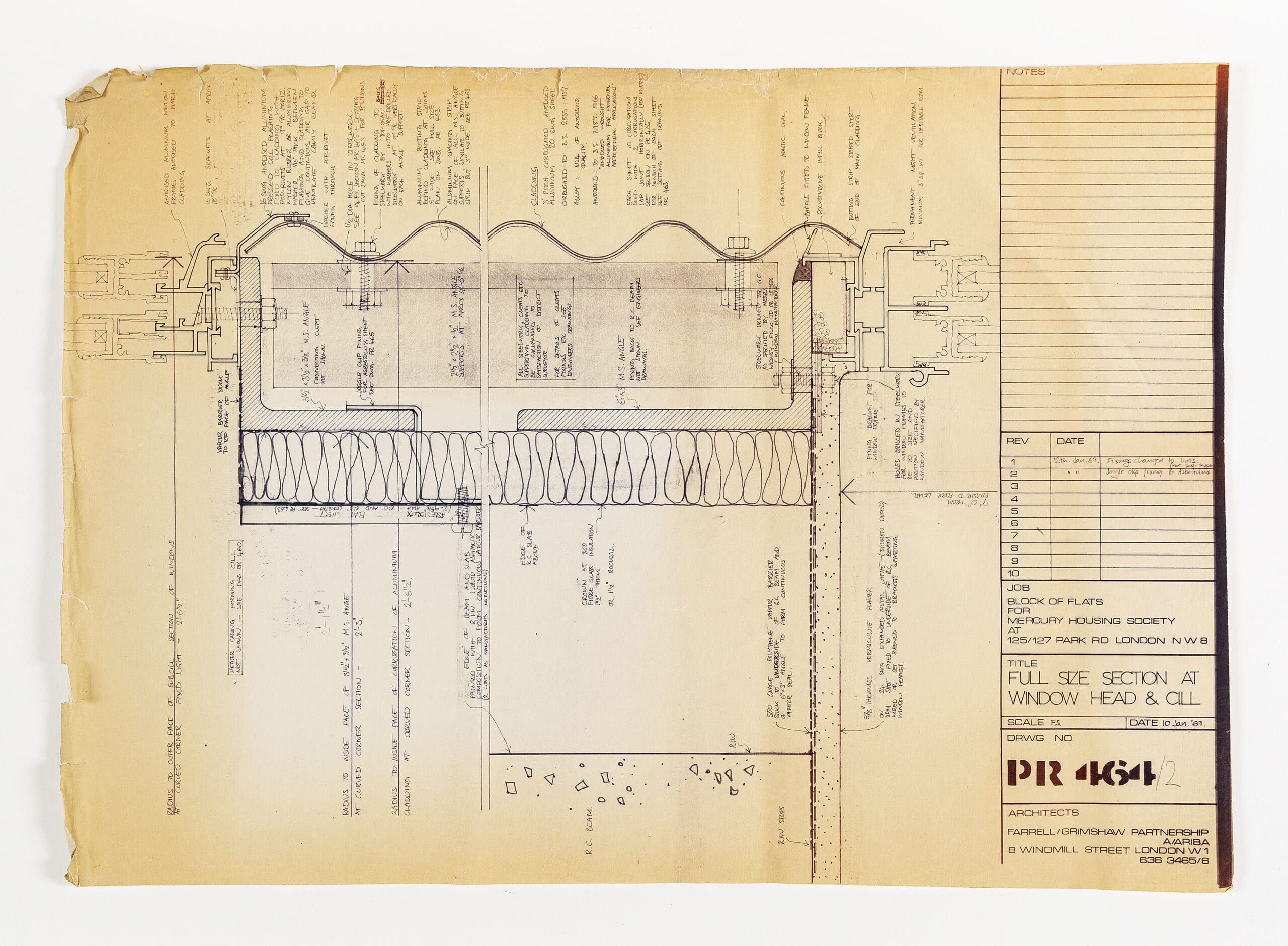

On first reading, then, the corrugated panel is another example, another moment of contestation between the old and the new, tradition and innovation, hand and machine and between rival social classes. But to frame the effect of the panel in such terms only is to blind oneself to the extent of the epistemological rupture that the panel as archetype has also created for global space production and for the practice of architecture generally. During the early part of the twentieth century, corrugated panels, now made of steel and not iron, shifted from being the futurist stalwart of Capitalism to just part of the backdrop of everyday life. Since 1830, corrugated panels have become a global phenomenon, the lingua franca of a universal architecture, built on the whole without architects. Nevertheless, the idea of the panel as a prefabricated component became, within early modernist architect’s hands (especially those who looked more to the Marxism of Hannes Meyer and Mart Stam than the phenomenological muteness of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe), central to the design and provision of working class mass housing and the production of space generally.

Contrary to expectation however, corrugated roof and wall panels were not destined to just slowly fade respectfully out of use, due to the onward developments of manufacturing technology. By the end of the twentieth century, corrugated panels would be known more by their infamy than their utility. Once the physical effects of Russell Harrap’s 1941 invention of reinforced asbestos corrugated cement sheet came to pass, the identity of the corrugated panel would shift from a useful to a monstrous entity.

The resulting fatalities from the use of asbestos stands at over one hundred thousand deaths per year. A large number we can imagine includes building workers, making the asbestos corrugated panel arguably the deadliest construction product of all time and certainly worthy of Morris’s description of corrugation as a pestilence.

Apart from the notable flowering of corrugated cladding during the High-Tech period, the legions of anonymous warehouses and the courageous avant-garde, the story of corrugation appeared at one point, to have largely concluded. However, against all odds, corrugation is back with gusto; many recent developer-led buildings now use corrugated metal panels or subtle allusions to the original sinusoidal cross section of Palmer’s invention, as a decorative façade motif. This recent manifestation signifies an attempt to connect with the aura of practical utility associated with early industrial manufacture, by ‘quoting’ the veritable art brut character of bare corrugated sheets. The re-emergence of corrugation is however without the ideological rigour of High-Tech and corrugation is now reduced to a form of architectural confetti, displayed for its ‘looks’ only.

The narrative arc of iron, asbestos and steel corrugated sheet is clearly complex and worthy of lengthy study and deliberation as it encapsulates the industrial revolution, the history of British colonial expansion, the conflict between Ancien Régime architects and a new class of engineers, the self-build practices of the poor and mass death.

No other building material comes close to the ubiquity and infamy associated with Palmer’s invention and Harrap’s later material innovation. Nevertheless, for architects, it is not just to the cultural history of corrugated iron that we should look for its wider significance, but to the idea of the panel itself as archetype for an architecture that is yet to be fully realised.

A future for the art of architecture is perhaps then only ensured if we choose to learn the lessons of Palmer’s radical solution, on how to create a lightweight dockyard roof to keep large quantities of imported tobacco, spice, ivory and coffee dry.

Notes

- William Morris, On the External Coverings of Roofs, in: Architecture Industry & Wealth, Collected Papers by William Morris (London: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1902). p. 267.

- For further information regarding Palmer’s patent and the development of corrugated iron see: Pedro Guedes, Iron in Building, 1750–1855: Innovation and Cultural Resistance (doctoral thesis, University of Queensland, 2010). Elizabeth Induni, Corrugated Iron Buildings in Britain: Cultural Significance and Conservation Challenges (doctoral thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2019).

– Gordon Shrigley