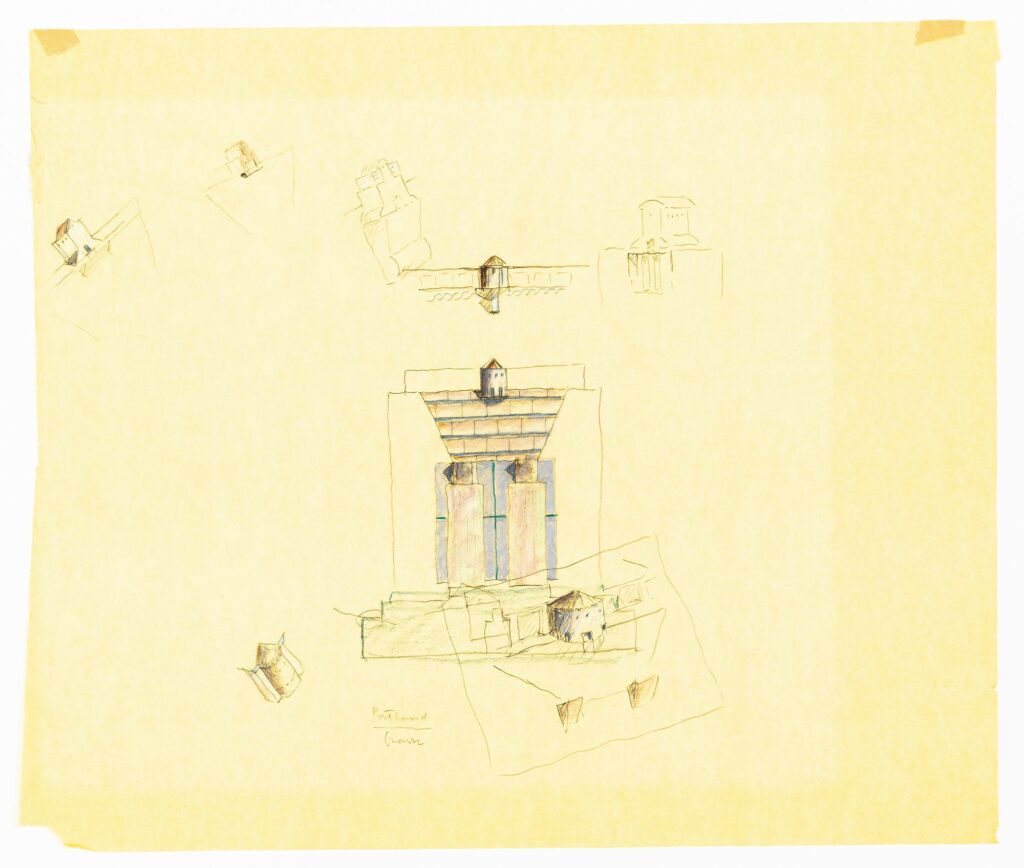

Michael Graves’ Rooftop Village (1985)

A notable aspect of the early criticism is the degree of vehemence with which the local architects opposed the scheme. ‘This is a dog building, a turkey,’ said the noted architect John Storrs, ‘I regret that we always have to face east for ‘the word.’[1] Another Portland architect, A.D. Benkendorf said, ‘I hope that others concerned about the future of downtown will join with me in urging the City Council to send ‘Graves’ Temple’ back to the East Coast.’[2] Pietro Belluschi, the one architect of international stature among these professionals, was hardly kindly. In a letter addressed to the City Council on behalf of the Portland Chapter of the A.I.A., Belluschi termed the Graves design an ‘enlarged juke box or the oversized beribboned Christmas package.’[3] He urged that the Graves build the building somewhere else, such as Atlantic City or Las Vegas, ‘Or better yet he should live a little while among us and absorb the genius of our city, and then begin anew.’ It was a statement that Belluschi would later regret. In general, however, the opposition was resigned. Said one respondent: ‘Psychiatry and architecture have always competed in the definition of mental disorders. This rivalry becomes visible in public buildings as megalomaniacal masonry, and I personally fail to see why our City Council should be hindered in its faithful adherence to tradition.’[4]

Graves did offer explanations of the symbolism he intended in the design of the Portland Building. Anthropomorphism would be represented in the building’s division into ‘head’, ‘body’, and ‘foot’. The paired pilasters would express the internal core of the building and they would only extend to the highest floor occupied by the city offices, therefore ‘supporting’ the final four floors that were to be leased to commercial tenants. The masonry garlands were to be interpreted as ancient symbols of welcome, and the statue ‘Portlandia’ would represent the city’s culture and industry. The green colour of the base was meant to represent foliage, the terracotta and cream-coloured middle section was to be suggestive of the earth, while the aqua-coloured roof would be analogous to the sky.[5]

Incorporating the overall elevation, colour and ornament of the design, the apparent symbolism of the building has been a source of critical concern and even misunderstanding. It was certainly Graves’ intention to include symbolic references in his scheme for the Portland Building, but some writers have read symbolism where none was intended or even possible. One example concerns the small group of structures that were to constitute a ‘village’ resting on the roof of the building. This design detail in the original drawing and model was removed as part of the well publicised submission of a second design solution meant to satisfy opponents of the original proposal. Five months after the building had officially opened, however, an interviewer for Progressive Architectureasked Graves, ‘The Portland Building, when first designed, was an acropolis with a small group of buildings on its head. What was the symbolic implication of removing them?’[6] This was a curious question, for although the structure had intentional symbolic meaning, the decision to remove the crowning buildings was a pragmatic one. Graves answered, ‘I thought it quite reasonable to describe with those buildings the paradigm of the city organisation. But it didn’t seem reasonable to the majority of the local fellows of the A.I.A. who were opposed to the building. So, now, in fact, the new symbol becomes the removal of that group of buildings.’[7]

Excerpted from The Critical Edge: Controversy in Recent American Architecture (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1985)

Notes

- Spencer Heinz, ‘Proposed City Office Building Design Called ‘A Dog’,’ Oregon Journal, n.d.

- Steve Jenning, ‘Chaotic or Poetic?,’ Oregonian, March, 1980.

- Belluschi’s letter and others from the local press have been published by Charles Jencks, ‘Post-Modern Classicism, the new Synthesis,’ Architectural Design, 50, 1980, 133-142.

- Lamar Tooze, ‘Keep Tradition’ (letter to the editor), Oregonian, April 16, 1980.

- See Steve Jenning, ‘Graves Aims at Building of Human Scale,’ Oregonian, March 16, 1980; Ian Blair, ‘Michael Graves’ (interview), Revue, Summer 1980, 25-29; Abraham Rogatnick, ‘An Interview with Michael Graves,’ Forum (Canada), September 1980, 4-5, 27-30; Joanna Cenci Rodrigues, ‘Interview with Michael Graves,’ Florida Architect, Fall 1981; Michael McTwigan, ‘What Is the Focus of Post-Modern Architecture? An Interview with Michael Graves,’ American Artist, 45, December 1981. Lisa fellows Andrus, ‘Taking Its Place on the Portland Skyline,’ Northwest Magazine,February 14, 1982, 6-8.

- ‘Conversation with Graves’ (roundtable discussion with Susan Doubilet, Thomas Fisher, David Morton, James Murphy), Progressive Architecture, 64, February 1983, 108-115, especially 114.

- Doubilet et al., ‘Conversation with Graves,’ 114. Of a different order is the symbolism that the building will project to the future as fantasised in Helene Melyan, ‘Temple of the Ancients, an Architectural Enigma,’ Oregonian, March 14, 1980, in which the author prophesied an archaeological symposium in the year 2980 devoted to ‘The Portland Dig.’