ETH Zurich: Casting the Cornice in Ticino

– Emma Letizia Jones and Erik Wegerhoff

From the fifteenth century onwards, the Swiss region of Ticino was famous for its stuccatori – the skilled decorative plaster workers that migrated down to Italy in search of work ornamenting the great palaces and churches of the Renaissance. Further generations of these craftsmen made their way over the Gotthard pass to France and Germany, and eventually to Britain and Ireland, where they adorned the country houses of the eighteenth-century aristocracy with plaster mouldings and grotesques modelled after the antique.

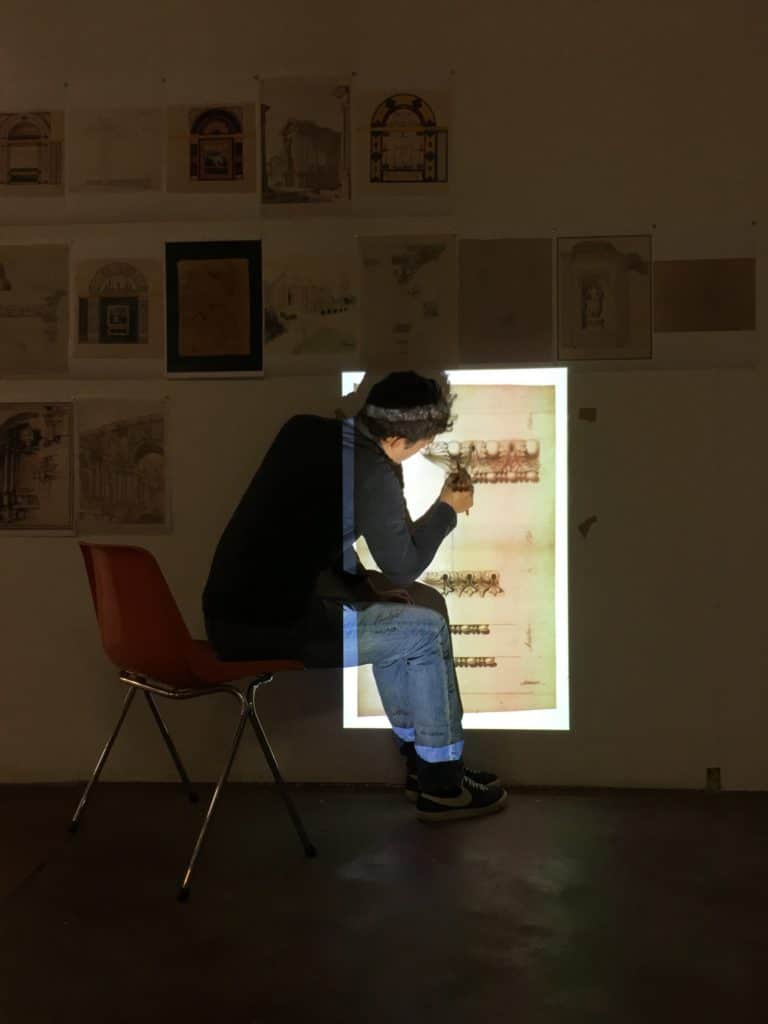

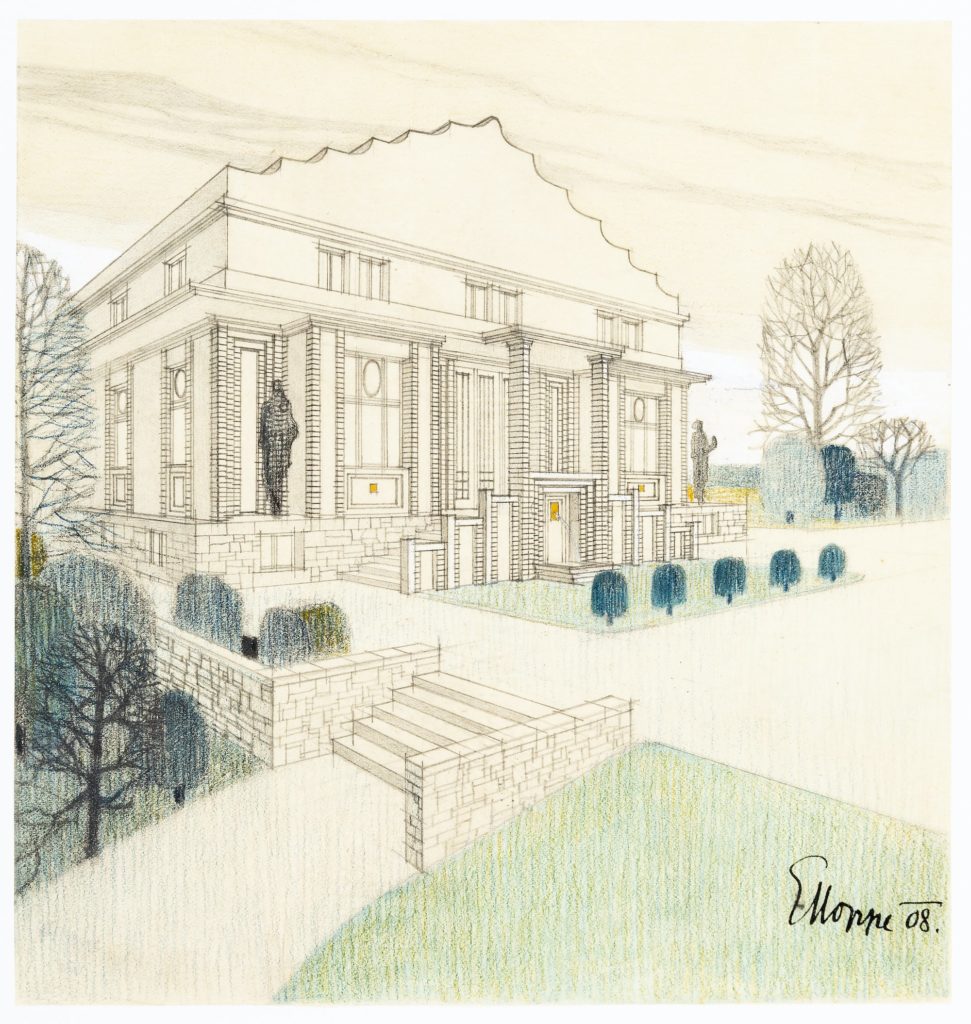

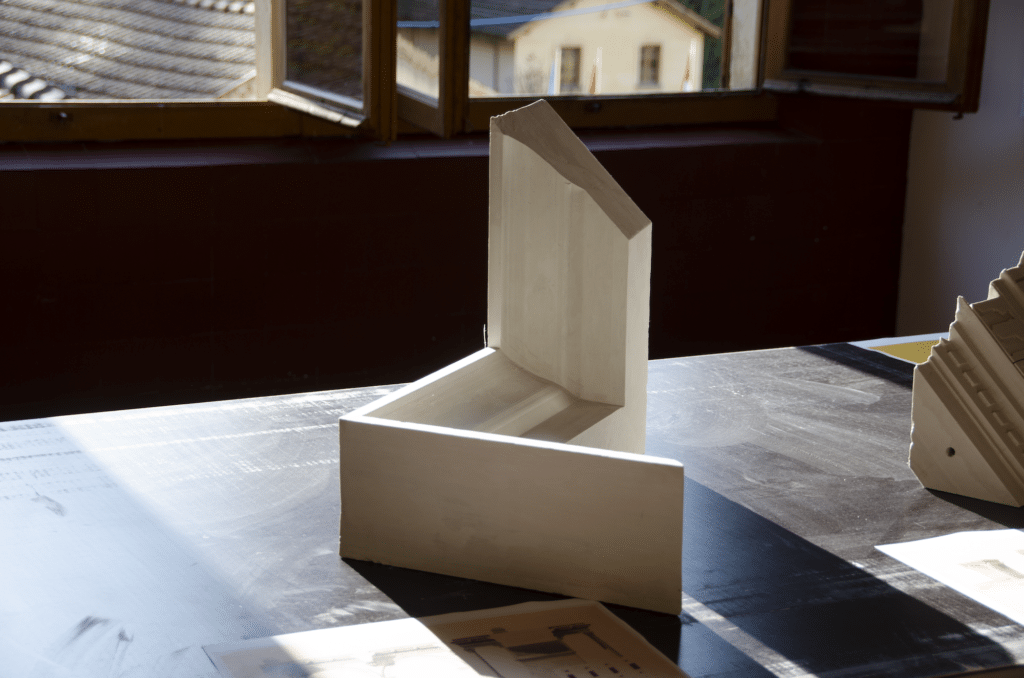

In October 2019, instructors from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich), together with eleven students, travelled back to Ticino to spend a week at the remote village of Aquila, home of the former local chocolate factory Cima Norma. Staying and working in this idyllic post-industrial complex, the students spent full days in a temporary workshop set up in one of the complex’s large iron-framed halls, casting architectural cornices in plaster. Through a creative process of translation, the students transformed the cornices depicted in drawings from different historical periods selected from the Drawing Matter archive into three-dimensional plaster objects for display, learning from historians of the region, local craftsmen from the valley, as well as other experts in plaster running moulds, casting and art fabrication. Students built their own tools to realise profiles and mouldings of their own invention, in response to these drawings. They then confronted the ornamental profiles they created with the functional factory context through a series of photographs.

In classical architecture, the cornice is defined as the crowning element of the building: an external moulding forming one of three principal members of the classical entablature, above the frieze and the architrave. Crystallised and abstracted into pure decorative stone by the Greeks, the cornice nevertheless contains the visual traces of an original timber structure that would have served to throw rainwater off the face of a building, and to form a communication between wall and roof. Because of its adherence to strict proportional rules, the cornice is an essential ‘finishing’ to the outward presentation of a building: a crowning feature without which the predefined proportional relationships of each part of the classical façade cannot work. By the eighteenth century, the cornice in this definition had been incorporated, along with other emblematic classical profiles, into a strict system of rules to be learnt by rote, on which the student or practicing architect could rely when needing to imbue his building with a classical ‘correctness’ of character. Yet despite the rather academic treatment of such profiles in architectural circles, the definition of the cornice had nonetheless continued to expand from the Renaissance onwards to eventually refer to any horizontal continuous moulding that forms the projected crowning feature at the top of a wall, internal or external, or other architectural element – a door, window or pedestal, for example. Much more than a decorative feature, the cornice also played a crucial role in mediating between an individual building and its urban environment. Within a room, cornices, by virtue of their formal allusions, could equate interior space with public space. Horizontal cornice lines could tie an urban fabric together, or break it apart.

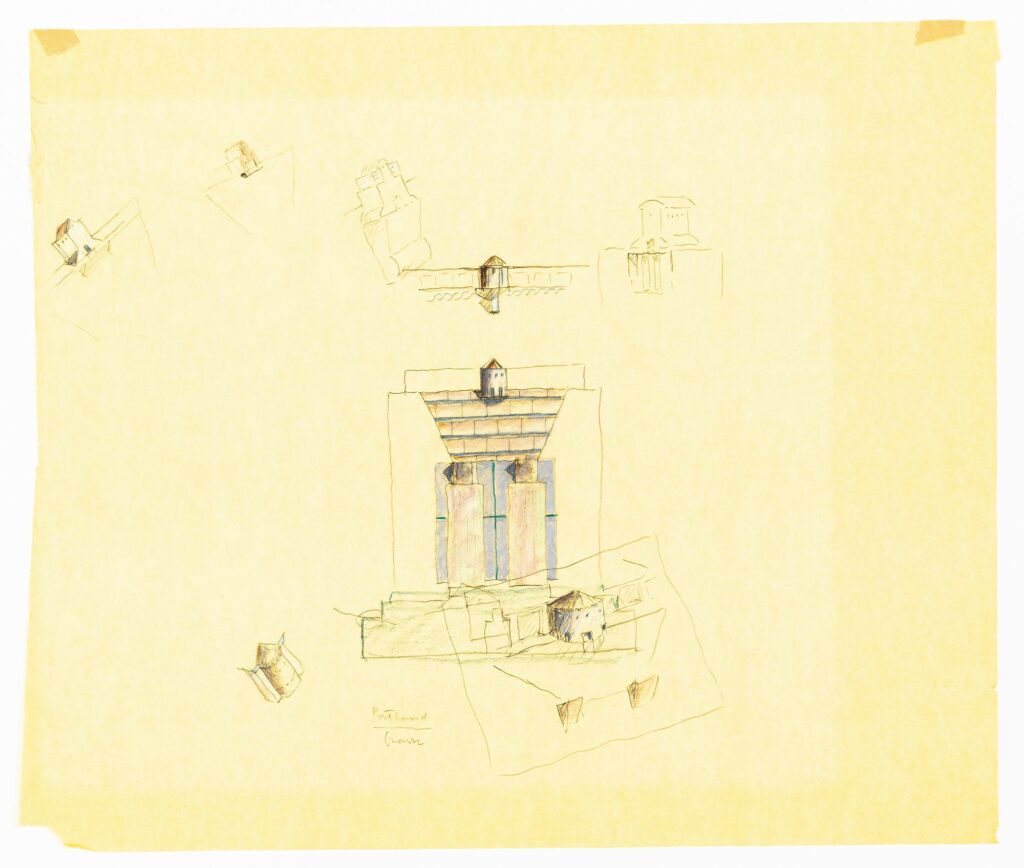

After being drawn, measured from ancient classical models, and theorised over centuries, the cornice was finally banned from modern architecture by such figures as Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier, only to make a triumphant and prominent reappearance in postmodernism. In our workshop in Aquila, drawings picked by students from the Drawing Matter archive featuring cornices from Antonio da Sangallo, Henri Labrouste, Hans Poelzig, Mies van der Rohe, Michael Graves and many others, acted in this spirit as the impetus for the invention of new kinds of profiles and mouldings. This prompted a final interrogation of what role the cornice may yet have to play in contemporary architectural design and discourse.

Student responses to drawings in the collection:

Workshop organisation: Emma Letizia Jones and Maarten Delbeke, Chair for the History and Theory of Architecture Prof Maarten Delbeke, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich), with Kathrin Füglister and Moritz Lehner.

Guests: Giacinta Jean, Giovanni Nicoli and Alberto Felici (SUPSI), with Carina Kirsch (Kunstgiesserei St. Gallen)

Students: Lorena Bassi, Gabriel Eggenschwyler, Ella Esslinger, Guy Keller, Mirjam Kupferschmid, Thorben Müller, Guillaume Pause, Patricia Pervan, Jonas Schüpbach, Moritz Schmidt, Ikonija Stanimirovic