Name(r)s of the Animals and Drawers

In Hoc Signo Vinces exhibition and a drawing workshop

‘Barely Traced, the true drawing escapes.’[1]

On a late night while reading Latife Tekin’s Zamansız (Timeless or Without Time)–a tale of love embedded in a lake, unfolded within the obscured semblances of a weasel and an eel–I found myself moving my lips, whispering: ‘Frii-iii-er-frii-ii-frii’. As I read the words printed on the paper, I hear their sounds in my head. I seem to pause and recite the affectionate meddling sounds of the lake: semblances of the birds, the eel, the weasel, the woman, the… :

‘Frii-iii-er-frii-ii-frii [… ] Frii-iii-ak-frii-frii […] Tıkı tıkı korr Korr Korr tıkı tıkı […] Civoyk civoyk tıkı tıkı tıkı […] Viginn viginn vigi gıd gıd vıgank […] Şişşşşşşt […] Çınnnnnnnn çın Çıngıl çıngıl çıngıl […] Kırs kırs meee meee kırs kırs eee […] Tak tak tak, Korr Korr Korr Civoyk Civoyk Civoyk […] Eeeeee eeee ninni de ninni […] Çarp çarp çarp! […] Tak tak tak civoyk civoyk civoyk! […] Hışş hışş hışş […] Vii vii viii Vick vicik vicik […] Sısssssss-sss fırıl- fırıl -fırızzz fır […] Cıp cıp cıp! Huvişşt huvişşt huvişşşt! […] Zınk zınk zınk! […] Viginn viginn vigi vigang! […] Vigi vigi vigang vigang! […] Cıks cıks cıkss! […]-Rogg rogg rogg! […] Farş farş farş uğn uğn uğn! […] Kırkç kırkç mee! Tak tak mee! […] -Çınnk çınnk frii! Gırç gırç Frii! […] Şşşşşşşt’[2]

*

Now, I am visiting Larissa Araz’s exhibition In Hoc Signo Vinces (2024) [in this sign thou shalt conquer] on display at Versus Art Project.[3] Taking its leave from the political questions of the naming of three native animal species in Anatolia by the Western scientists exploring the Ottoman Empire, and then the change of their names by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Turkey later on, Araz examines this question in four separate sections: ‘Scientist’, ‘Language’, ‘Animals’, and ‘Hunters’. Araz delivers her work as follows:

In the ‘Scientist’ section, the audience is greeted with wall paintings and zinc plates hung on them. These charcoal-drawn wall paintings depict the sketches and records made during the period of exploration, emphasizing the transience of those records, while the patterns on the zinc plates depict the role of contemporary technologies in the creation, distribution, and control of knowledge.

In the ‘Hunters’ section, visitors are invited inside through a video of a fire creeping through a door gap. Images of hunters placed around the fire question the visual representations of hunting and prey.

In the ‘Language’ section, there is a cabinet inspired by the display formats in natural history museums. A tree, compressed inside as if squeezed in, is placed within it; developed inspired by the drawing ‘The Tree of Life’ by zoologist, philosopher, painter, and explorer Ernst Haeckel. The tree symbol used to define the families and origins of species has evolved into an image also used to separate races and families over time.

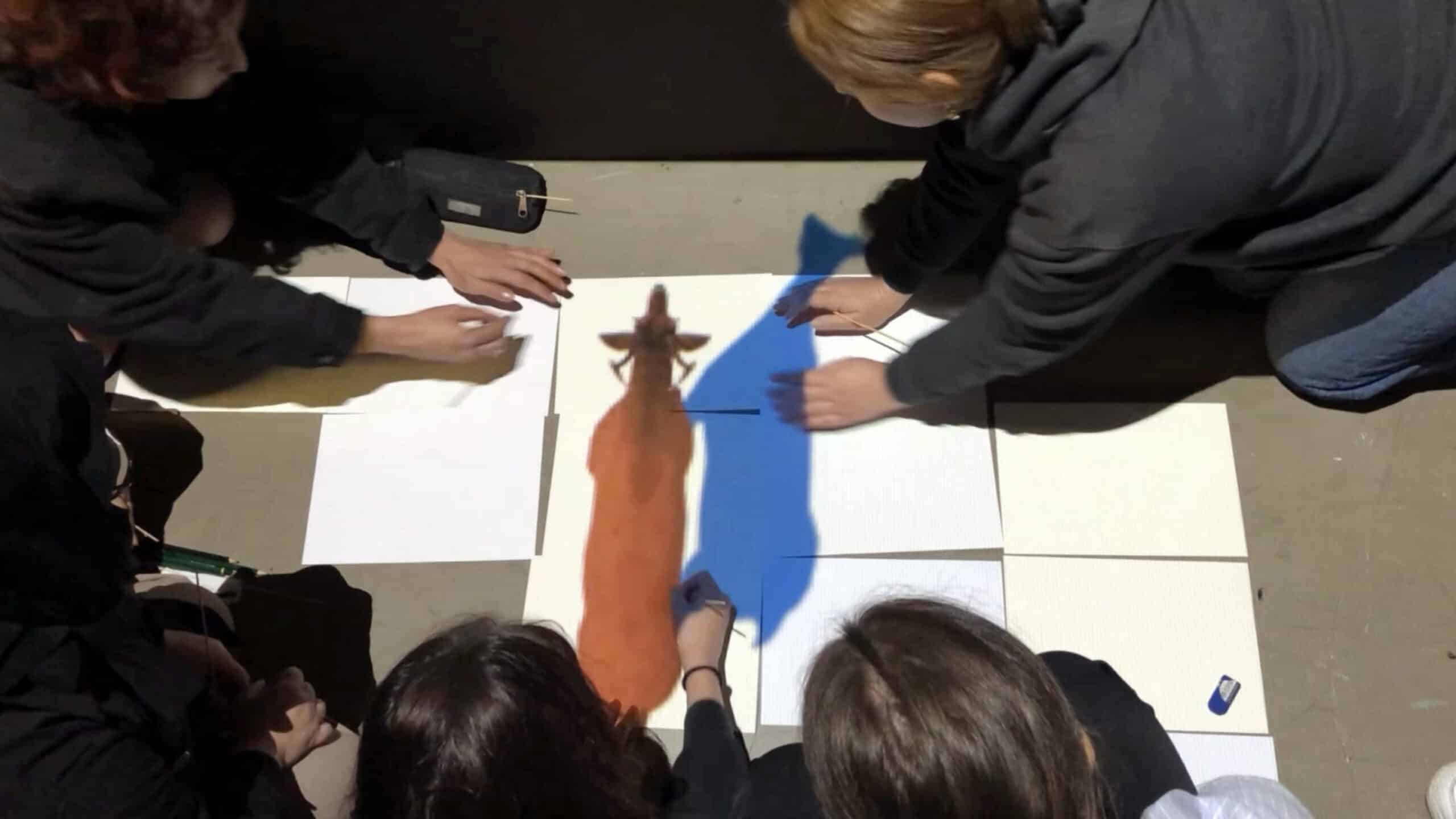

Roe, wild sheep, and foxes walking along the corridor make up the ‘Animals’ section. These animals, walking with ghostly transparency, engage in a dialogue with the viewer about their relationship with the region they belong to.[4]

In the ‘Animals’ section, I negotiate with animals projected on the ground, crossing from one side of the wall to the other side of the wall. I do not pass the corridor. I recall a serene tranquillity–I recall no sounds of their steps passing through the space, touching the ground. As they walk, as their hips and tails slightly move from one side to the other side, I am filled with affection. I fear something might unexpectedly disturb this tranquillity. Yet, the passage of the animals repeats and repeats without any disturbance. Trusting this recurrence, I feel an urge to kneel. As their strong shadows move along with them, I wonder whether I can reach between the animal and its shadow.

*

Should we call them by their proper names? I remain in silence, kneel and let them pass through my hands, my arms and my body.

*

Catherine Ingraham, in her book Architecture and The Burdens of Linearity (1998), referring to Jacques Derrida, discusses the anxiety of patriarchal genealogy in relation to giving proper names, or, as called by Derrida, ‘the first violence of language.’

‘The giving of a proper name is thus a dream of self-identity, a fantasy of presence, within a system of differences that has always already deferred and severed this name from its property and its self-sameness. The inheritance from father to the child is typically the passage of a proper name, and with it one’s property, either real or felt. To systematically pass along name, history, property, and the proper procedure for this passage is the reason, Derrida more or less states, that writing as an inscriptional system came into being. It was a tool that could be used to record increasingly complex patterns of descent and family history.’[5]

Cross-reading Levi-Strauss’ ‘A Writing Lesson’ and Derrida’s ‘The Violence of the Letter’, Ingraham sets forth that architecture (as an inscriptional system) operates similarly–‘inscribe[s] these patterns, these narratives of family residences, into space’, through marks and lines.[6] About the idea of marks and lines, Ingraham finds ‘everything tortuous’ and ‘nothing succinct.’[7] In her reading, the relation between proper, property and propriety is critical. Ingraham elaborates on this relation with an example of a client (owner of property) who expresses her/his wishes ‘in the (proper) terms that architecture has already put in place: living room, bedroom, bathroom’ based on appropriate occupancies of spaces which later on could be claimed for these proper acts.[8]

*

The power of the proper name to create an authorial and historical passage of meaning from one generation to the next is a serious matter, as it holds the impetus ‘to stop the play of language.’[9] What if unnamed? Would it still be possible to call them?

*

‘Şişşşşşşt […] Çınnnnnnnn çın Çıngıl çıngıl çıngıl […] Kırs kırs meee meee kırs kırs eee’[10]

*

I recall another passage by Ingraham: ‘The proper name, which is not just the name of a person or thing, not just a noun, is also the means by which something exists or comes into existence. To paraphrase George Bataille, only the animals that got a name were saved (by Noah). The amorphous something / someplace of someone or something before it is named is precisely that: amorphous, without form, without formal place, without formal existence.’[11]

Do historical significations, classifications, passages conventionally seem to show the tendency to ‘claim’, ‘save’ and ‘archive’ things, relations, forms, styles that can be catalogued and filed under proper significations and abandon the ones that cannot be? Do they declare them to be ‘alive’ or ‘dead’ by saving them under proper significations or by abandoning them? What remains of the not saved (the abandoned)? What remains of the saved? It is perhaps one of the stigmatic questions. Are the remnants images of likenesses or indexical traces on the ground or bones, fumes, ashes, memories, names, …, us…? What of ‘the abandoned’? ‘The shadows walk’; architecture seems also to be haunted and haunting with a deep feeling.[12]

*

In what ways would a drawer engage?

*

At this moment, I think that we might remind ourselves of some of the discussions on paintings of Veronica. Veronica, etymologically derived from ‘vera’ meaning true and ‘eikon’ meaning image, is used to refer to sacred images, that are thought to bear the ‘true’ impression of Christ’s face. Along with Veronicas, Shroud of Turin is a cloth that is believed to be Christ’s actual burial shroud, imprinted with Christ’s dead body, resulting in an image that emerges through direct contact with the body. Withstanding the representation of likeness, embodying essence, Veronica is believed to bear the trace of a corporeal, living touch.

*

acheiropoieton, meaning ‘not made by human hands’.

*

Zeynep Sayın writes that these kinds of images that track the trace of the corporeal touch and that seem to ‘erupt from a nameless depth’ have a kinship to the traces that animals leave on the ground and liken to the traces left by fire and ash in space, and that they are perturbing for the modern eye as there is an ungraspable field that goes beyond the visible.[13] It is the corporeality of the image that is, through the traces of bodies of the past, charged in their absence with a proximity that is, in turn, charged with a fright for the unknown.[14]

*

As I kneel, as I stretch my hand out through the projection of the animals, I feel the animals passing on my body. I wonder, in what ways do the animals touch the ground, touch my body?

*

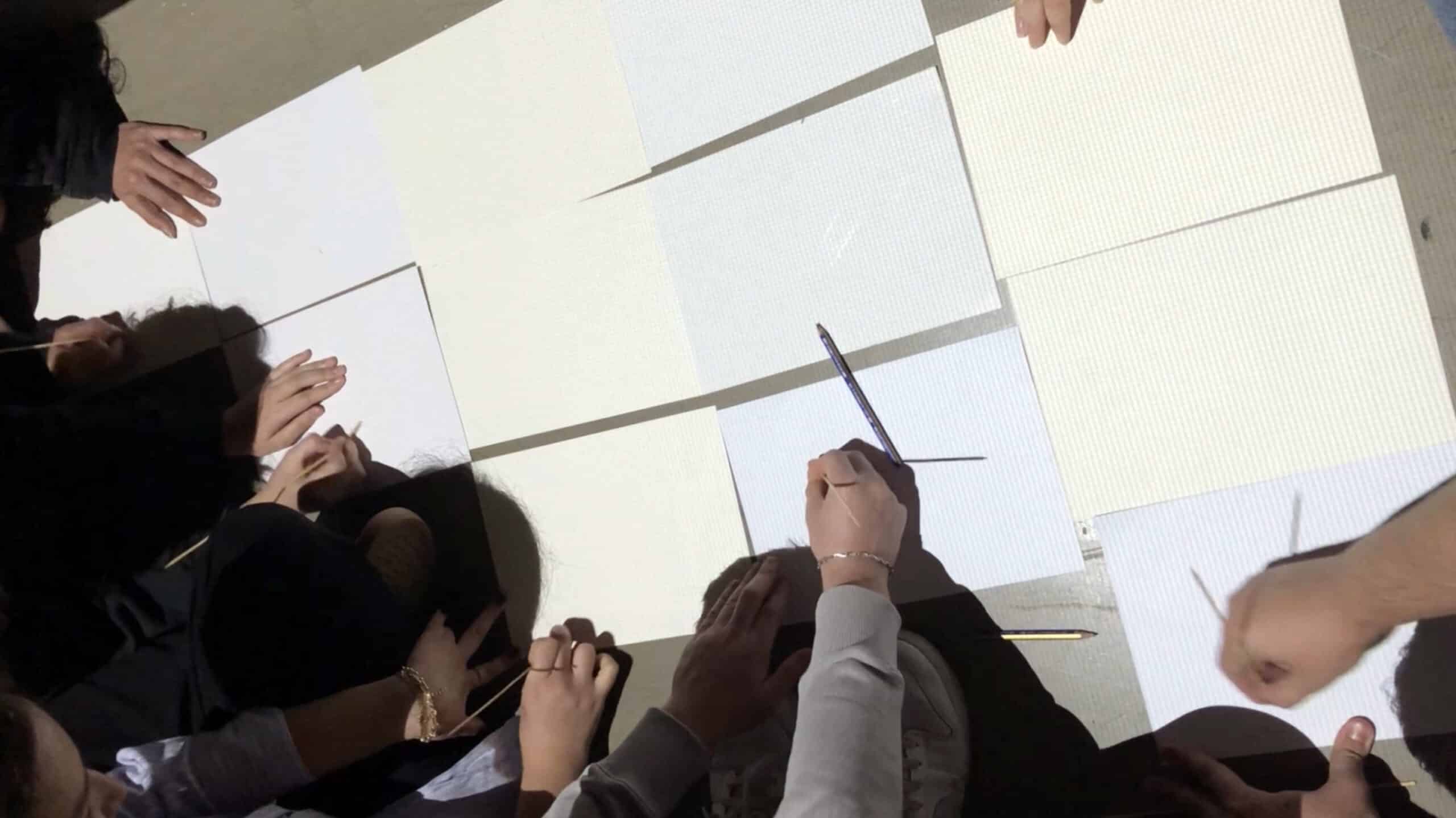

Some days later, I am back at the gallery with some of my elective course DrawingConstructions participants.[15] Prior to engaging with the ‘Animals’ section, we visited the room of the ‘Hunters’, the room of the ‘Scientist’ and the ‘Language’. We observed the video installation, we looked at the engravings and charcoal drawings of the animals displayed in frames or directly drawn onto the walls.

*

With DrawingConstructions, we intend to take the role of the ‘drawer’, to track the trace of the corporeal touch that seems to ‘erupt from a nameless depth’ and to enter into the ungraspable field that goes beyond the visible.

*

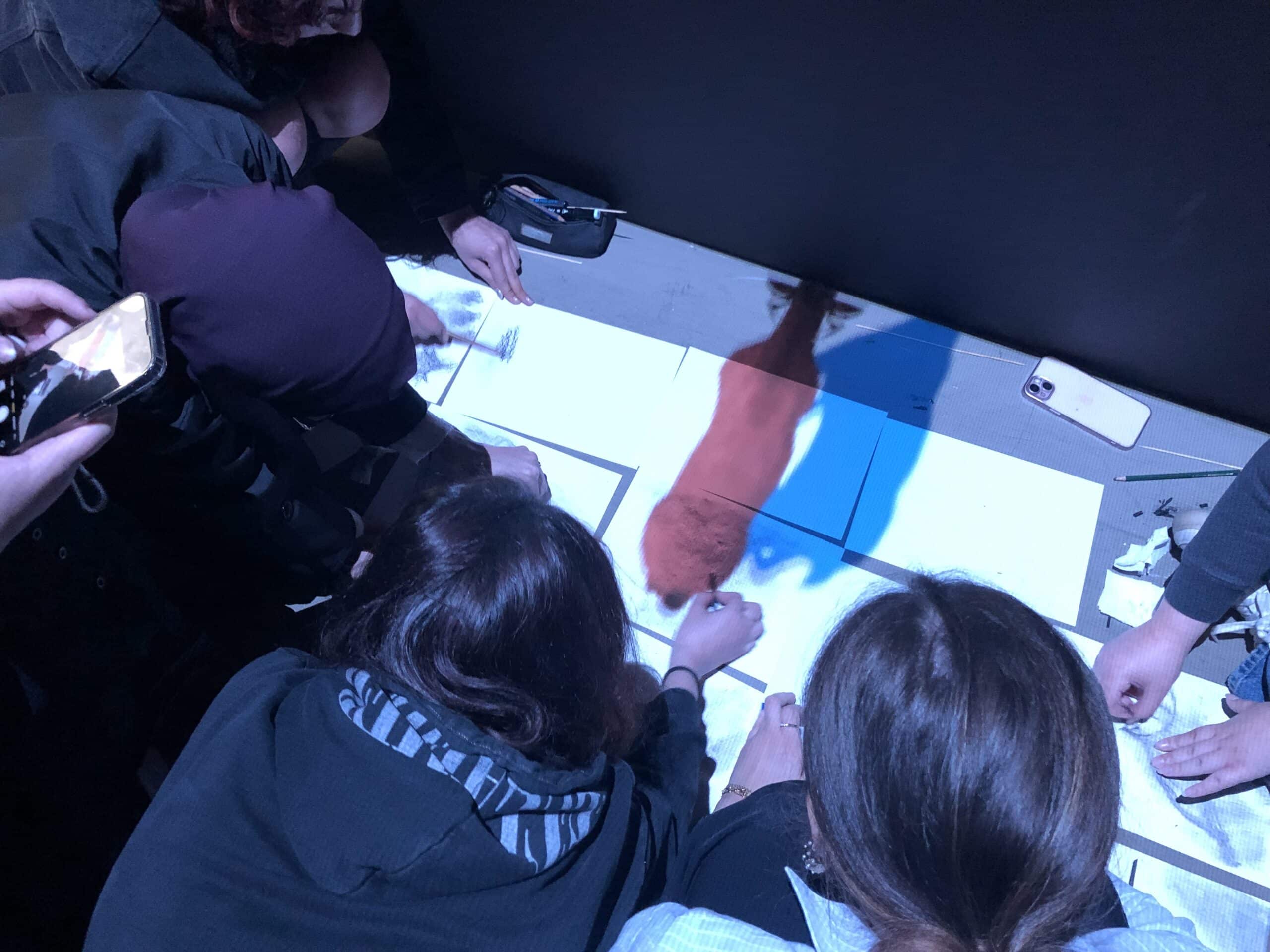

We all kneel, lay papers on the ground and wait. It is an affectionate wait–waiting for the animals to pass in their tranquillity. A procession that is replayed and replayed. There… are we hunting? We are afraid of accidentally taking the role of the hunter; we hope to engage in the role of the drawer. Rather than capturing or arresting the image, we intend to let the drawing escape the gaze. With wooden sticks in our hands, we kneel, try to move along with them, try to touch their movement. Some of the animals pass very quickly. We continue to carve the traces into the flesh of the paper. As we carve into the paper, the sticks do not leave any stained marks, just a cut into the paper. We do not see our carvings.

*

After a while, we go over our carvings with charcoals, pencils, and soft pastels to reveal all the carvings on the paper. Our drawings could be considered to be technically an engraving, but our way of drawing diverges from the ones we have seen in the room of the scientist in terms of its intention to evade a representational attitude. Rather, we think of Hélène Cixous’ statement ‘barely traced, the true drawing escapes.’[16]

Notes

- Hélène Cixous, Stigmata: Escaping Texts (London: Routledge, 2005), 16–17.

- Latife Tekin, Zamansız (İstanbul: Can Yayınları, 2022),13–25.

- Larissa Araz, In Hoc Signo Vinces, 2024, <https://www.larissaaraz.com/inhocsignovinces> [accessed 20 February 2025]

- Ibid.

- Catherine Ingraham, Architecture and The Burdens of Linearity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 21.

- Ingraham, 21.

- Ingraham, 4.

- Ingraham, 32.

- Ingraham, 32-33.

- Tekin, 19-21.

- Ingraham, 32.

- Eugene J. Johnson, ‘What Remains of Man – Aldo Rossi’s Modena Cemetery’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol.41, No.1 (Mar 1982), 38-54.

- Zeynep Sayın, İmgenin Pornografisi 3rd Print (İstanbul: Metis Yayınları, 2013 First Published in 2003), 19.

- Sayın, 31, 47.

- SDrawingConstructions is an elective course and an experimental Collective drawing project initiated and led by Bahar Avanoğlu at Istanbul Bilgi University since 2017. (https://pair-folio.com/drawingconstructions)

- Cixous, 16-17.

*

With special thanks to Larissa Araz, Mert Ünsal and Alkım Ekermen.

Participants of the Workshop: Alaa Alrnawout, Dilgesu Arıcan, Selin Cengiz, Bilge Duru, Imene Chanez Hemal, Deniz Özkan, Burak Sezen, Emre Şimşek.

*

Bahar Avanoğlu (PhD, ITU) is an independent architect-researcher with an interest in the esoteric practices of architectural drawings. She teaches design and drawing studios at Istanbul Bilgi University and MEF University, and initiated DrawingConstructions as an experimental project in 2017. She is the editor of Şiir/Mimarlık: Binanın İhlali (İletişim Yayınları, 2022) and co-organizer of the exhibition Unbuildings (İstanbul, 2024).

– Bahar Avanoğlu