Nancy Goldring: Drawings and Foto-Projections

– Leann Davis Alspaugh and Nancy Goldring

The following interview is reproduced from the publication Distillations: Nancy Goldring, Drawings and Foto-Projections, 1971–2021, published by ORO Editions. The interview was conducted by Leann Davis Alspaugh for The Hedgehog Review.

The Hedgehog Review: In the 2014 summer issue of The Hedgehog Review, we ran two of your works ‘The Traveler Remembers Friday’ and ‘Borobudur Broken Heads’. You describe these as foto-projections. Can you say a little more about your process on these works?

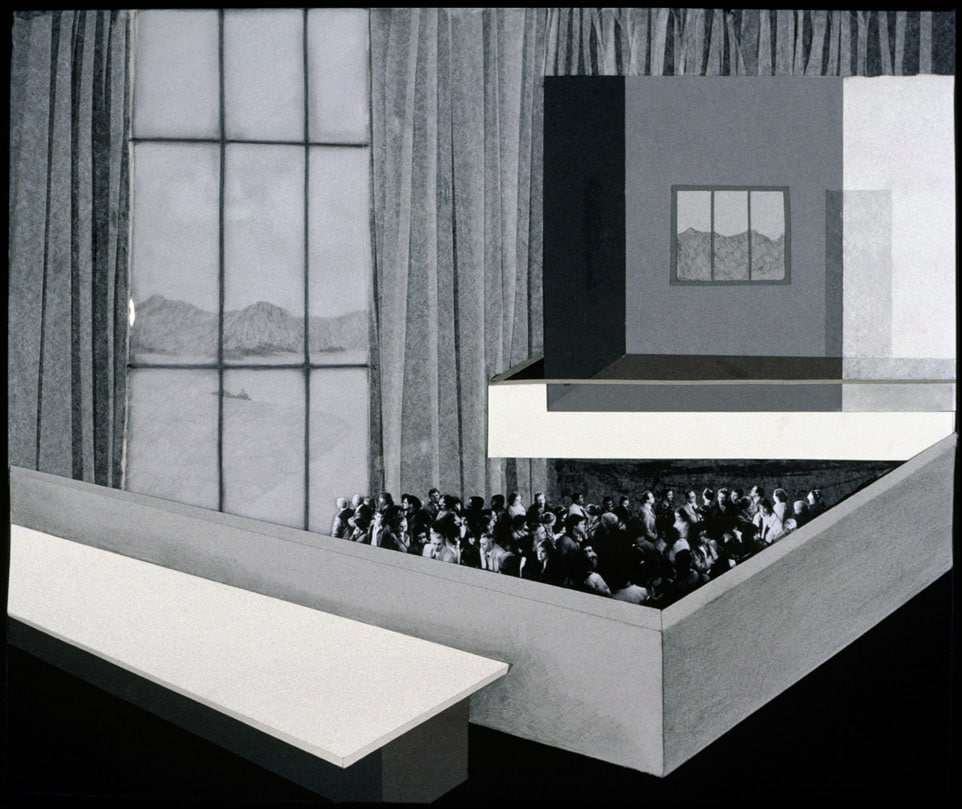

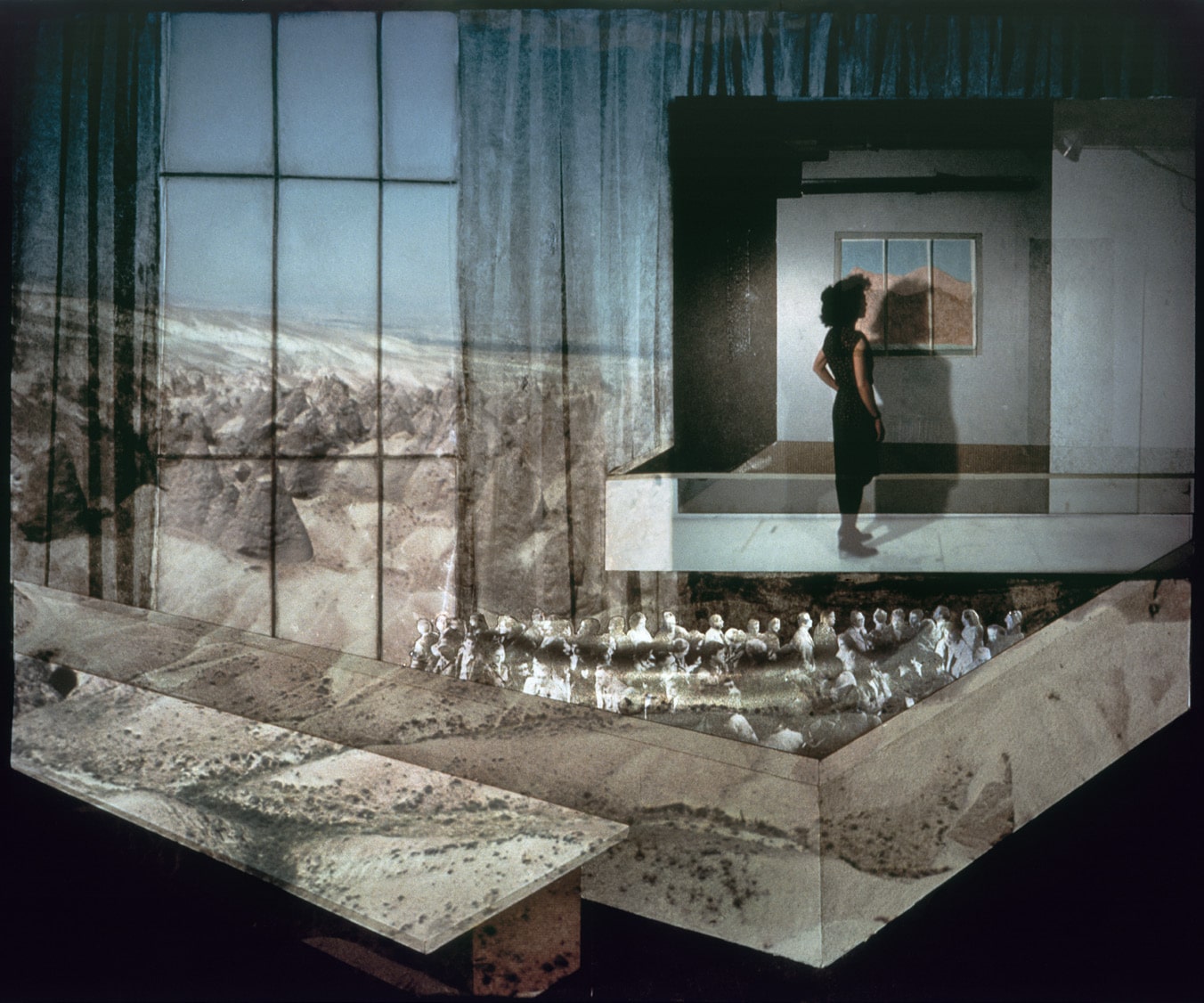

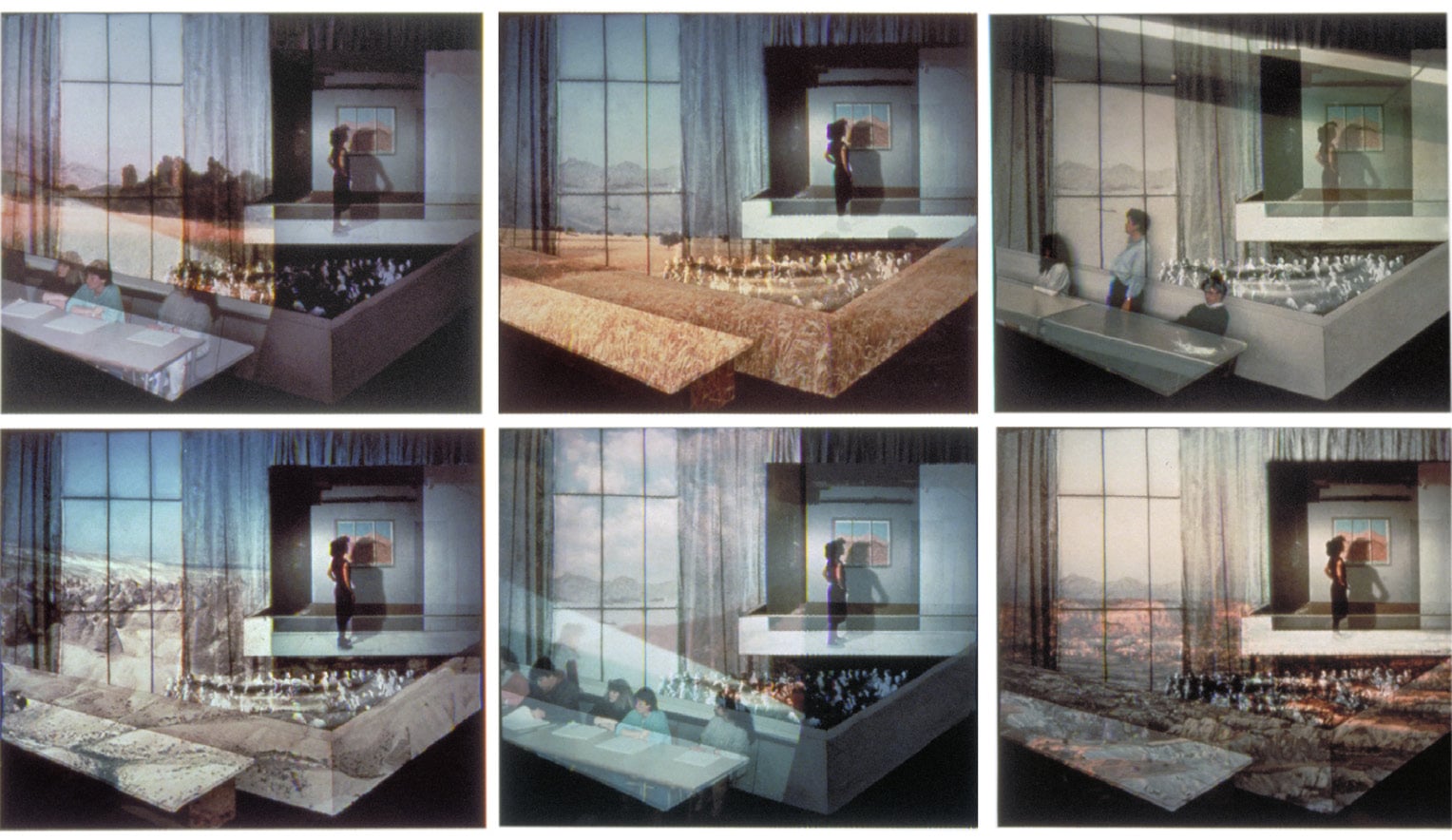

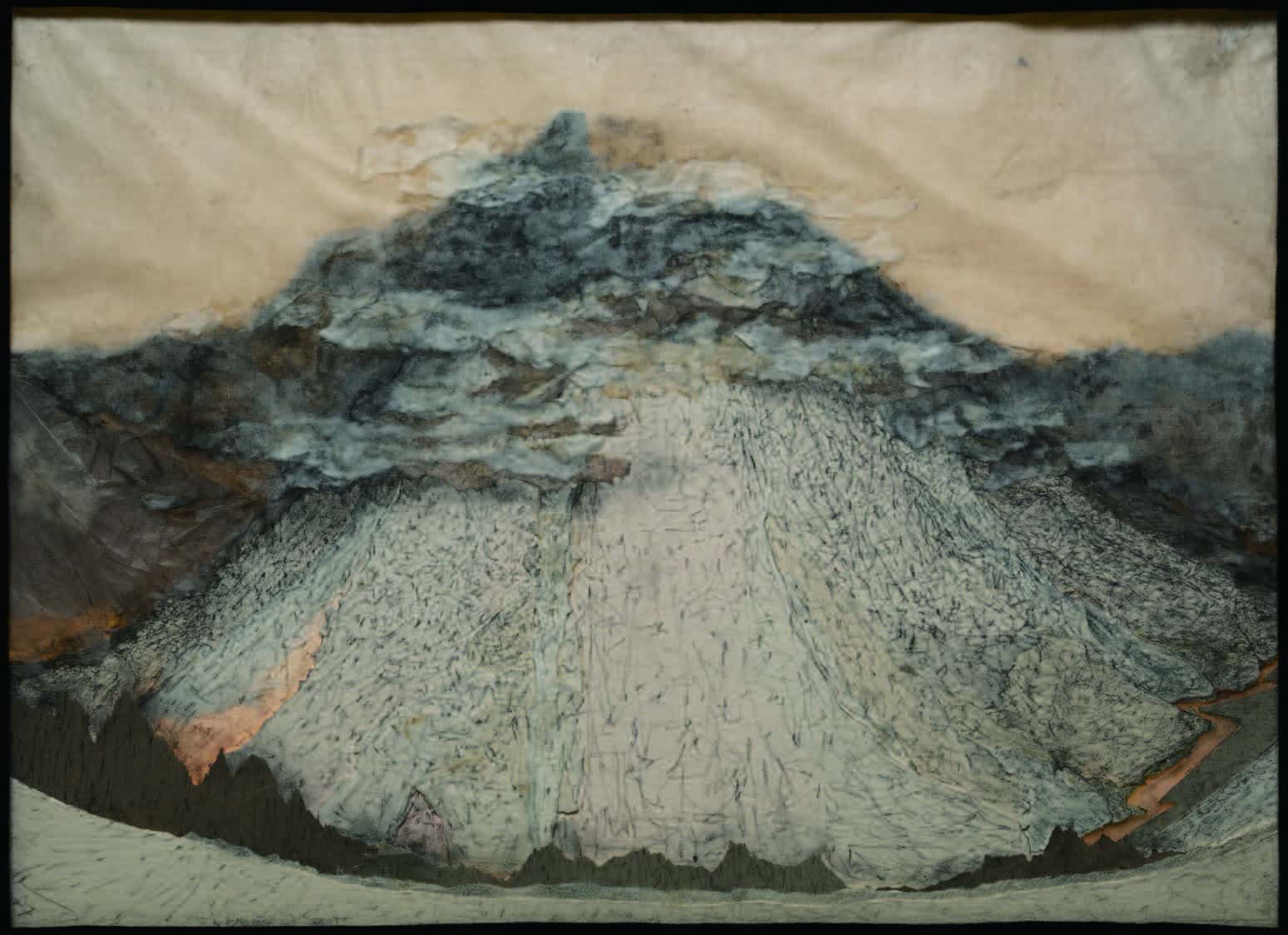

Nancy Goldring: While my personal approach to making art has remained relatively consistent over the last forty years, it is important to understand that I have no prescription or formulaic system. Rather, I have contrived a way of working that will generate the images I have in mind. The process is therefore always evolving, based on invention and discovery. Generally, to develop my thought or render the image I begin the process with sketches and, ultimately, a finished pencil drawing. I then transpose that drawing into a low relief using paper, cloth, mylar, threads, etc. Using multiple slide projectors, I project fragments of slides that I have taken previously in situ back onto the relief, which functions as a kind of screen. Working in the dark with a large format camera, I photograph the model with the superimposed projections to produce what I have called ‘foto-projections.’ Each image, therefore, has the same relief model as its architecture, and different slide information. The sequence of foto-projections suggests various modes of looking—contemplation, rumination, or reverie.

THR: What is your art background? Formative experiences?

NG: Though I was always drawing as a child growing up in St. Louis, I never officially studied art, opting for art history in college (art wasn’t an acceptable major at the time). Perhaps most formative was my experience studying in Florence, first at the university and later on a Fulbright. I spent most of my time with what would now be called ‘conceptual architects.’ It was an exciting moment during which traditional categories were being challenged and boundaries between disciplines were beginning to dissolve—for example, one didn’t have to be a photographer to incorporate photography into their work or an architect to produce images of ‘place.’ We were all intensely politically engaged. Perhaps naively, together we proposed new approaches to making art, believing that artists and architects could collaborate to transform public space without relinquishing our individual artistic endeavours. It was an exciting (if short-lived) moment, and the two years in Italy had a profound effect on my way of thinking and working when I returned to the US.

And then there was the Renaissance. I have long been exploring ways of representing the three-dimensional world on a flat surface or in relief form. In Italy I was able to research the origins of linear perspective first-hand (the subject of my Fulbright). By examining and elaborating on that system in my work, I hope to reveal its basic cultural meanings and to ponder its stunning irrationality, while proposing new ways of describing space inclusive of time.

Also important in my formation was my encounter with the late art historian Leo Steinberg in the early 1970s. He was/is the writer I most admire, and his early support of my work encouraged me profoundly. His focus on ‘looking,’ together with his unrivalled use of language and breadth of culture helped form my thinking about making art.

THR: It seems that your work has many influences—surrealism, pictorialism, photo montage, collage, even video. Can you tell us more about your artistic influences?

NG: I have always been intrigued by syncretic images. So rather than specific ‘isms’ or particular media, it might be more accurate to say that I am interested in recombinant approaches. Does it really matter whether it is a painting or a photograph? I find American viewers are most interested in how images are made, but I am more concerned with finding an appropriate language for the image—whatever medium works best.

And rather than looking at general trends or movements, which are useful designations but always diminish the individual work of art, I feel more comfortable thinking about how specific artists have affected my vision. The art works from which I have learned most or with whom I have found affinities span an enormous gamut—from Assyrian reliefs to the Theodosian Obelisk base of 390 AD, to Piero della Francesca, Parmigianino, and Mondrian. The early work of Vito Acconci, Gordon Matta-Clark, and James Turrell were as important as that of architects’ Alessandro Anselmi and Massimo Scolari. Perhaps the artist/architect Michael Webb, of the group Archigram, whose exquisite drawings grapple with notions of infinite space while focusing on the quotidian, has had one of the most profound effects on my image-making.

On another level, much of my work also connects with what I am reading, almost like osmosis, it seeps in subliminally—whether the poetry of Wallace Stevens, the writings of Michael Taussig, or the novels of Javier Marias. I may borrow a title of a poem or deploy a structural device from someone—and allow it to find a visual equivalent.

THR: Describe how you use the idea of layers in your work.

NG: I don’t think of them so much as layers but rather as alterations in the surface of things. By shifting the weather or state of mind—by changing the sky, the shadows, the scale, or the proximity of the viewer, I can alter one’s experience of the place. The diverse images in a series are all ‘true.’ The trick is to make the projected layers meld into a cohesive, convincing image of place—whether an actual locus or merely a moment from a dream remembered—that resonates with the original site and that reveals aspects of the place in a way that a single snapshot can’t. When the projections work, they all fit together like a jigsaw puzzle—creating a credible, if implausible world.

THR: Much of your work has come out of travelling. How does being an artist influence your perceptions of other cultures? How does what you see and experience abroad enter your work?

NG: I began travelling when I was fifteen and never stopped. Because most of my work comes from what I see around me, if I am in New York City, Peridenya, Sri Lanka, or Sarteano in Tuscany, my work involves finding a way to evoke, depict, or represent what I experience in that place. Though careful observation comes first, my process involves research: detecting palimpsests in the architecture or observing how people move and inhabit the place. Of course, as an outsider one can never fully understand the history and culture of another place, but perhaps my work can be understood as document of the attempt to do so. It also registers where art fails to achieve full understanding. And perhaps its tiny successes indicate the importance of the attempt.

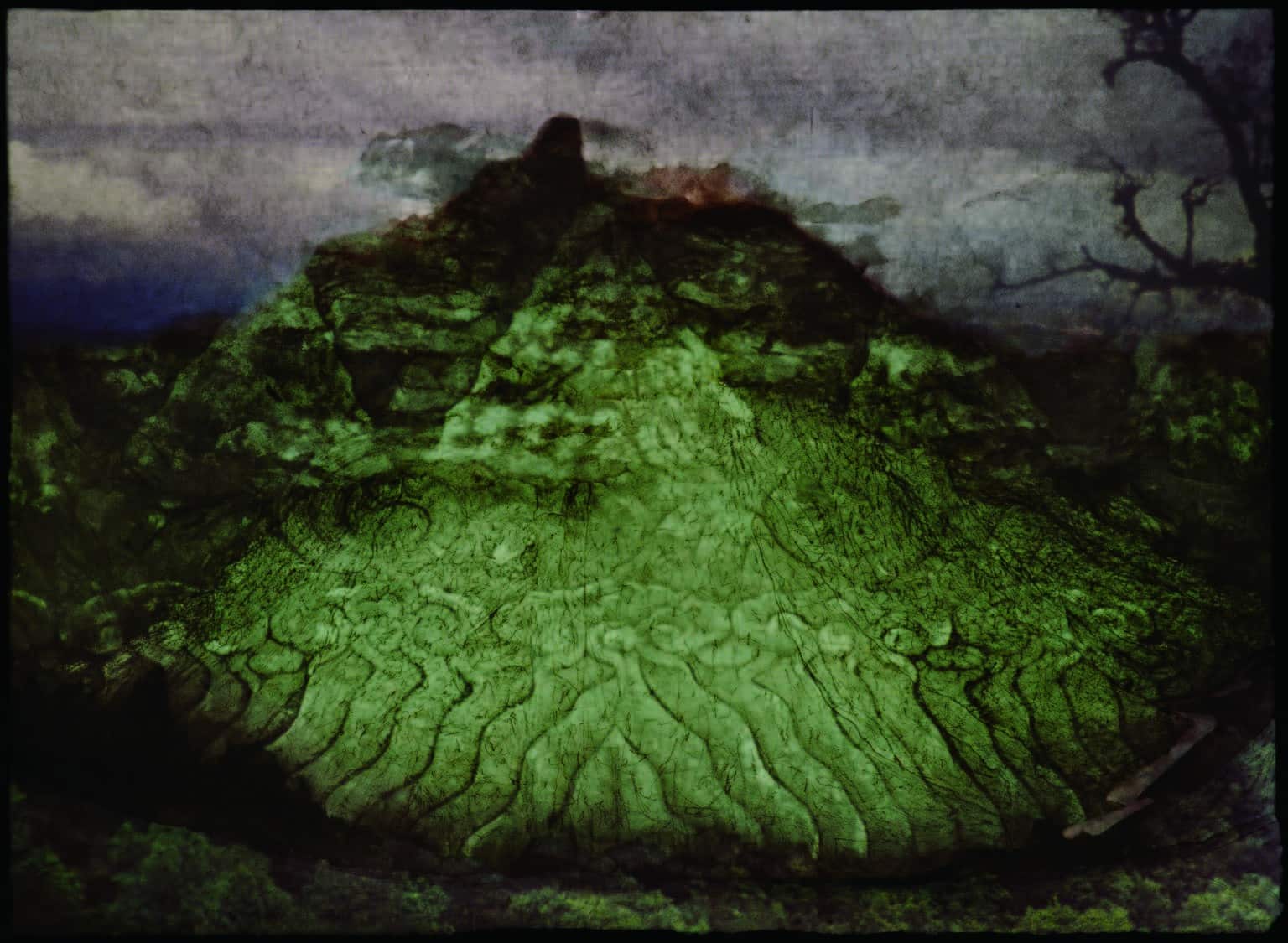

For example, the series ‘Place Without Description’ (an inversion of the title of a poem by Wallace Stevens) conjures a site I visited in western China near the border with Burma. From my perch high over the Yantzee River, I had observed how a secluded Tibetan monastery presides over the valley. Having spent time grappling with the Chinese modes of representation, I tried to experience this highly spiritualized site through non-Western eyes. As I did so, a different kind of relationship with the natural world emerged, as the viewer, untrammelled by a Western perspective system that privileges a single vantage point, is allowed to wander freely into the natural landscape.

THR: Have you recovered from the damage done to your studio by Hurricane Sandy? Has this experience had an effect on how you work, or has it entered your work in some way?

NG: I try not to think about it too much since the loss of thirty-four years of work is unfathomable. There was a moment, though, in which the destruction felt almost liberating—as if I could free myself from the past to better concentrate on things current. There seemed no point in trying to salvage work that had been submerged under nine feet of asbestos-contaminated briny water for a week, and I could only move on. I set up a temporary studio in a friend’s loft and got back to work.

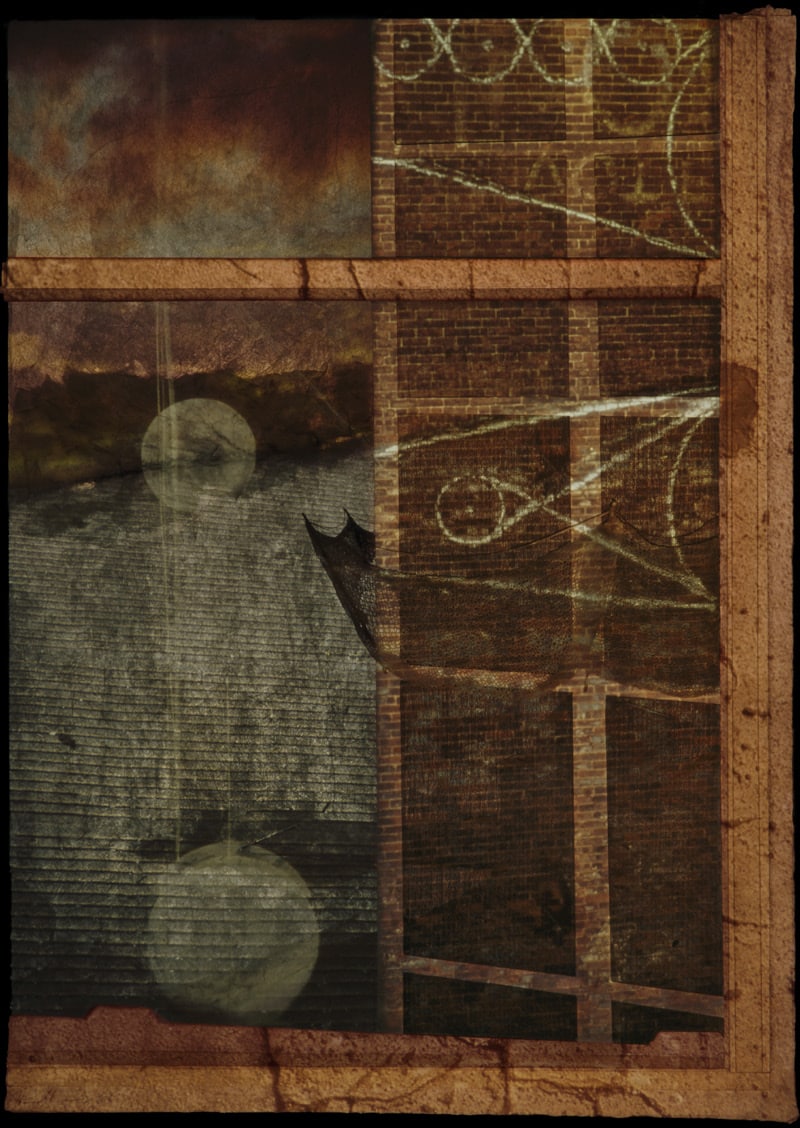

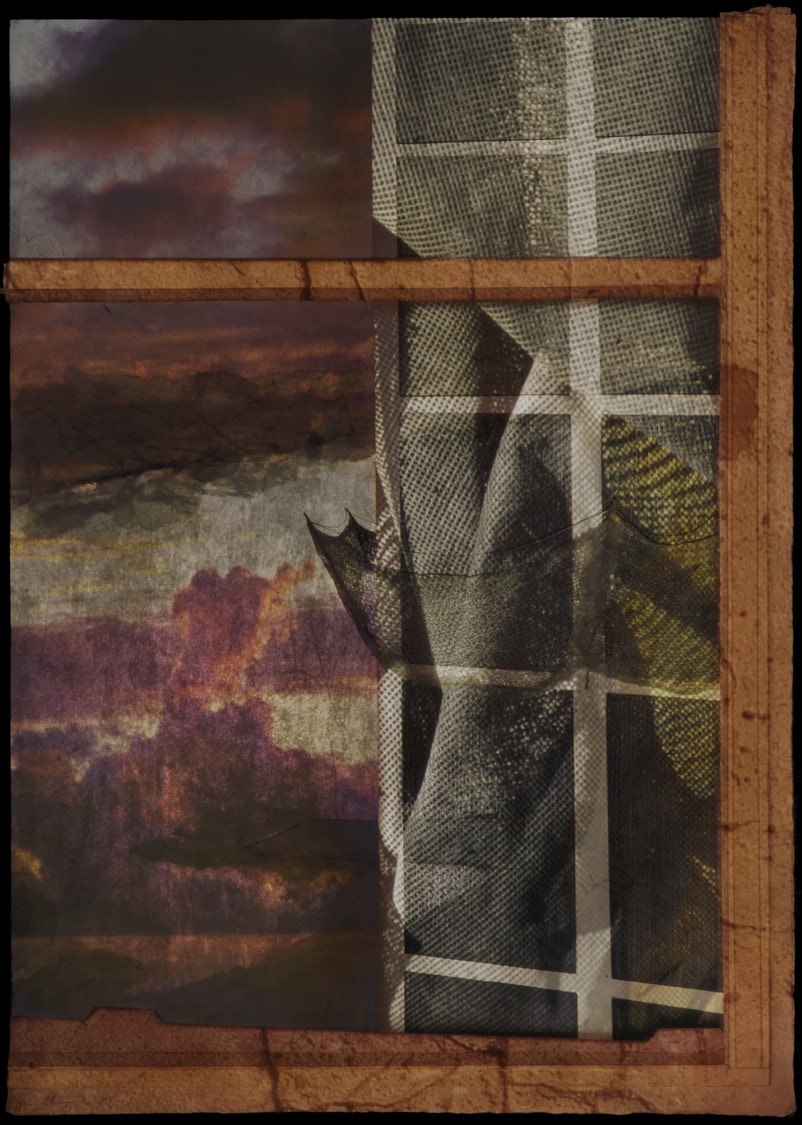

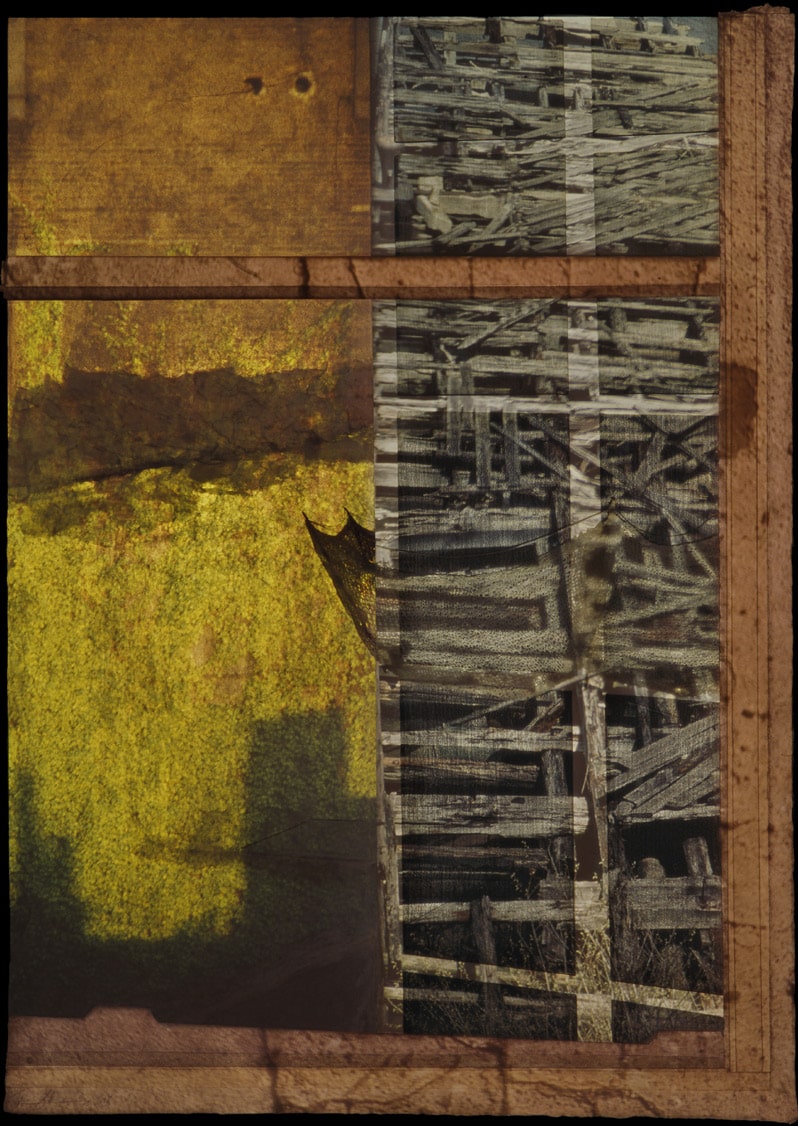

The night of the storm and the early morning after, I spent drawing what I had seen from the window: horizontal driving rain and a chaos of swirling lumber threatening to shatter my window. I had just completed a series entitled ‘Urban Amnesia,’ based on the view out of my studio window onto the Hudson. In this earlier piece I examined the way urban growth often destroys any sense of historical continuity and personal memory tied to place. Using the drawings inspired by the storm and the same view from my window, I developed a new series that I called ‘Urban Alchemy.’ My intent was to evoke the sea change that took place with the hurricane. I had never before attempted to record an actual event of such magnitude. The city had become vulnerable and its fragile infrastructure incapable of self-defence.

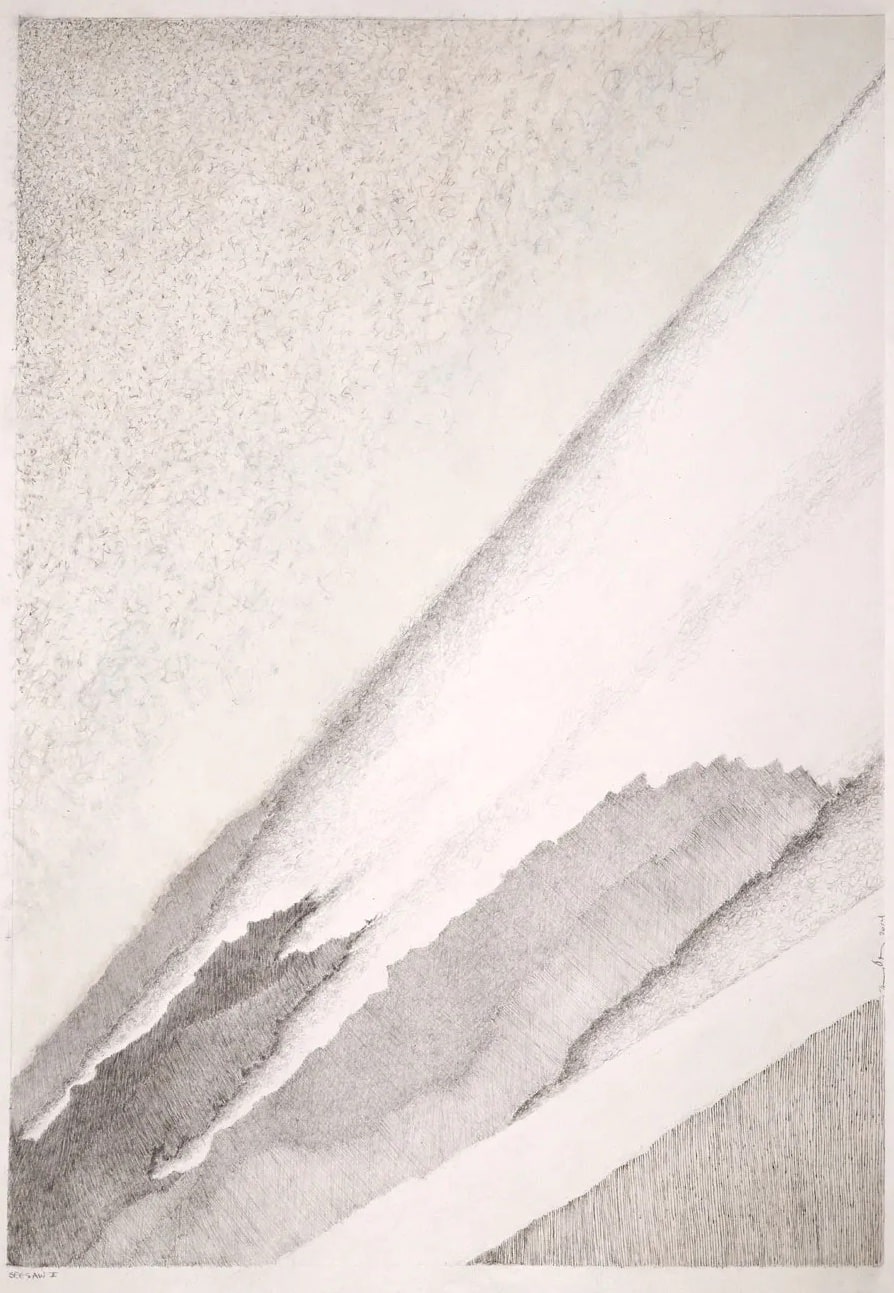

457 × 610 mm. Courtesy of the artist and ORO Editions.

I had also lost the studio where I had been projecting for thirty years, with all of its customised equipment. ‘Urban Alchemy’ is the first piece made in my new (too small) workspace in a friend’s loft. Having lost the studio, it occurred to me to wonder if I needed to continue this intricate and labour-intensive way of making art. Should I find another way to work? ‘Urban Alchemy’ answered that question for me.

THR: Tell us about some new work you are doing.

NG: At present I am in the midst of the final shoot of ‘Sea Saw’, a piece I began last summer while in a small town in Puglia, Polignano a Mare. Every day I drew the view from my balcony, carved into a dramatic cliff high over the sea. I couldn’t fit the spectacular view with its ever-expanding horizon onto the page—the drawing pad felt much too restrictive. To suggest its breadth, I turned the pad forty-five degrees so that the horizon sliced the page diagonally. The images invert the built townscape and the rocky natural setting to mimic the kind of dizzying precariousness that I felt in my perch over the sea. I hope to finish it by the fall to present the series at a conference on Italian landscape at the University of Leicester.

THR: What sort of contemporary cultural trends, if any, find their way into your art?

NG: The contemporary trends that might affect me directly are those most promoted in the highly commercialised art worlds of New York and at the international art fairs. I find it difficult to generalise about these ‘trends’ packaged like fast food for easy consumption. The trends I appreciate most are those smaller voices—work that can be found by lifting up rocks. The emergence of alternative online publications represents a positive force, offering alternative ways for many younger artists whose goal isn’t to fit into the system.

It is good news that one can see abstract painting again. There is a certain level of abstraction in what I do—I would situate the vision somewhere at the edge of abstraction like Mondrian’s ‘Pier and Ocean’. I feel as if my hybrid process is in itself, a sort of abstraction or a way of abstracting from perception and therefore the renaissance of this less literal form of representation and depiction promises new space for growth.

My work has often been shown in exhibitions with ‘conceptual’ artists. I share in common with them the notion of working in series of non-narrative sequences because it generates propositions about art and questions the nature of making it. For reasons that I will never fathom, conceptual artists today generally believe that one must relinquish the visual in order to focus on the concept. I have little in common with this strain and see no reason why visual thought should be considered a distraction from ‘the idea.’ One hopes mere looking can become a transformative experience uniting thought and feeling.