Pan Scroll Zoom 10: Studio Othenin-Girard

This is the tenth in a series of texts edited by Fabrizio Gallanti on the challenges in the new world of online architectural teaching and, particularly, on the changing role of drawings in presentations and reviews. In this episode, Guillaume Othenin-Girard discusses his studio at the University of Hong Kong which explored the Mei Foo Sun Chuen estate.

Quarantine drawings

A chronicler is a person who bears witness to historical events as they happen. Most often a chronicle is written, sometimes it is factual, but always retains a certain fiction that comes from its author’s point of view. For the students in the BAAS 4th year design studio to bear witness to the covid-19 pandemic, it was fundamental to respect a certain sequencing that chronicling the moment demanded: (1) to observe, (2) to understand, (3) to act. Drawing has the capacity to compress all three phases together; it allows us to project ourselves and to act at a distance. Drawing takes us beyond mere facts and brings out underlying issues. During the pandemic, we became the chroniclers of our isolation and began to understand that it threatened the very idea of the collective, revealing and intensifying latent fragilities within our relationships with others – and otherness.

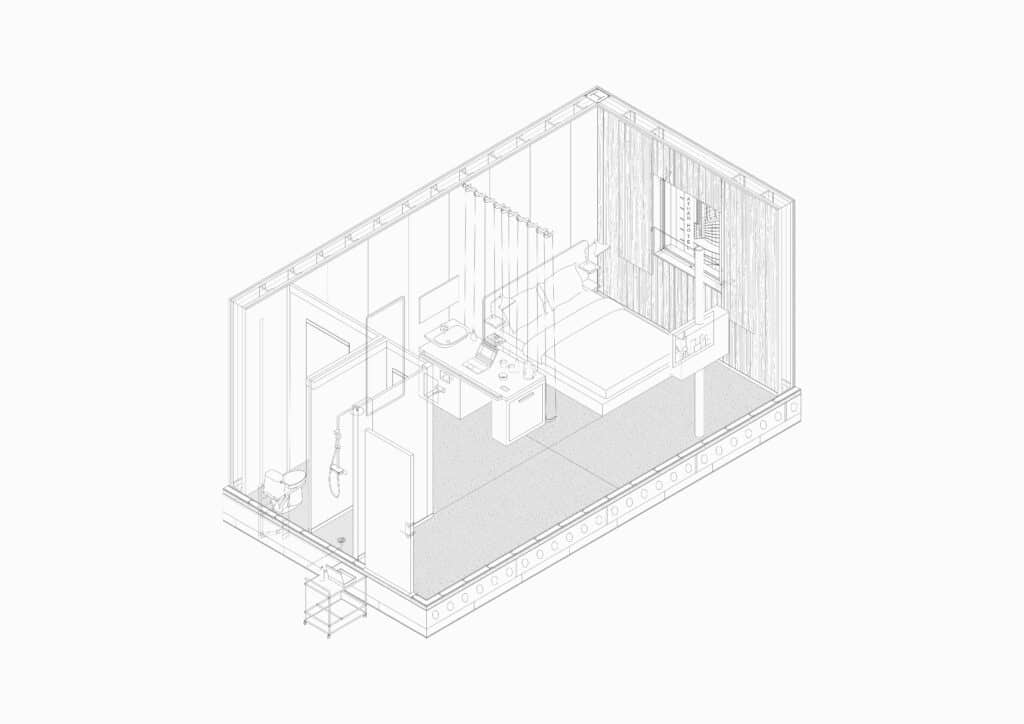

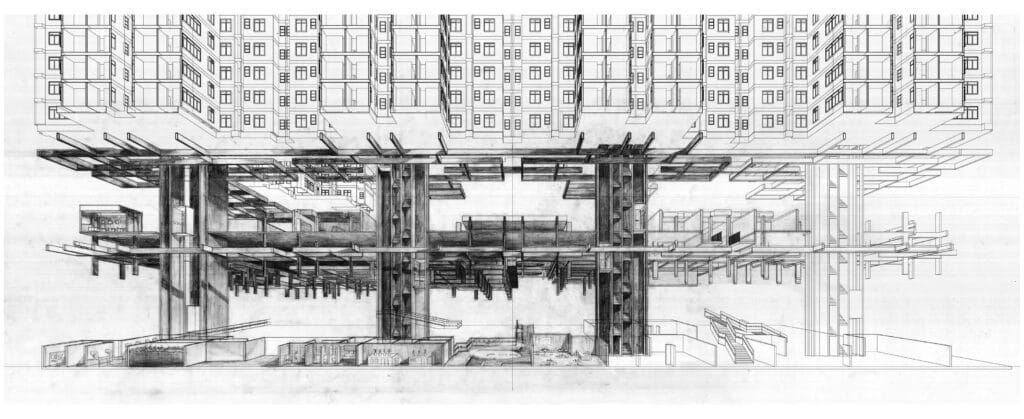

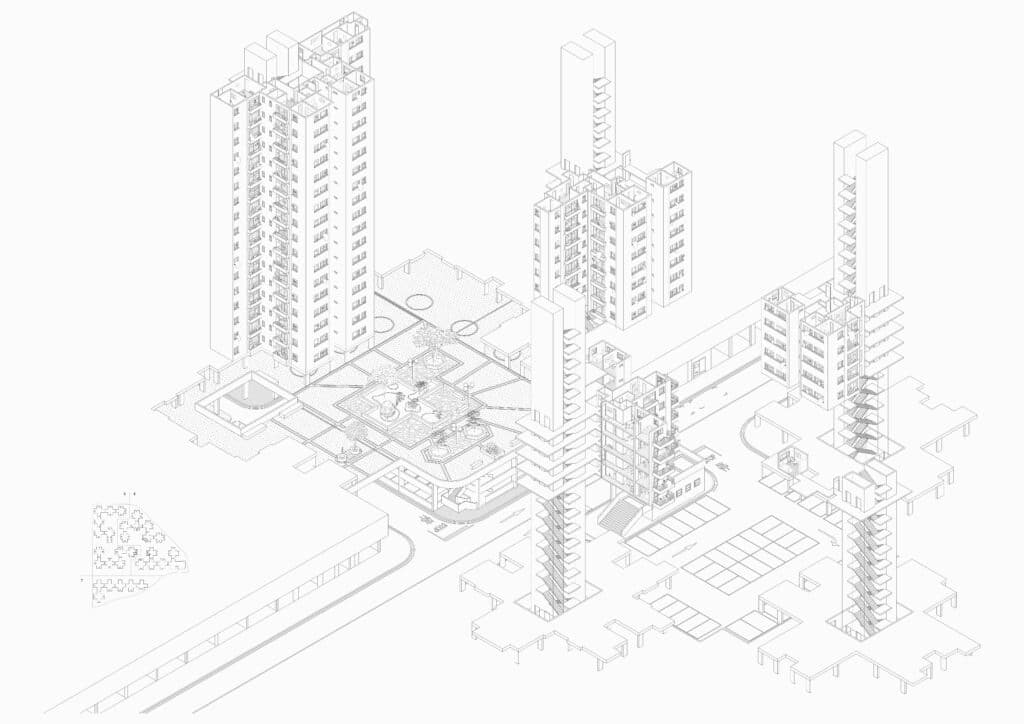

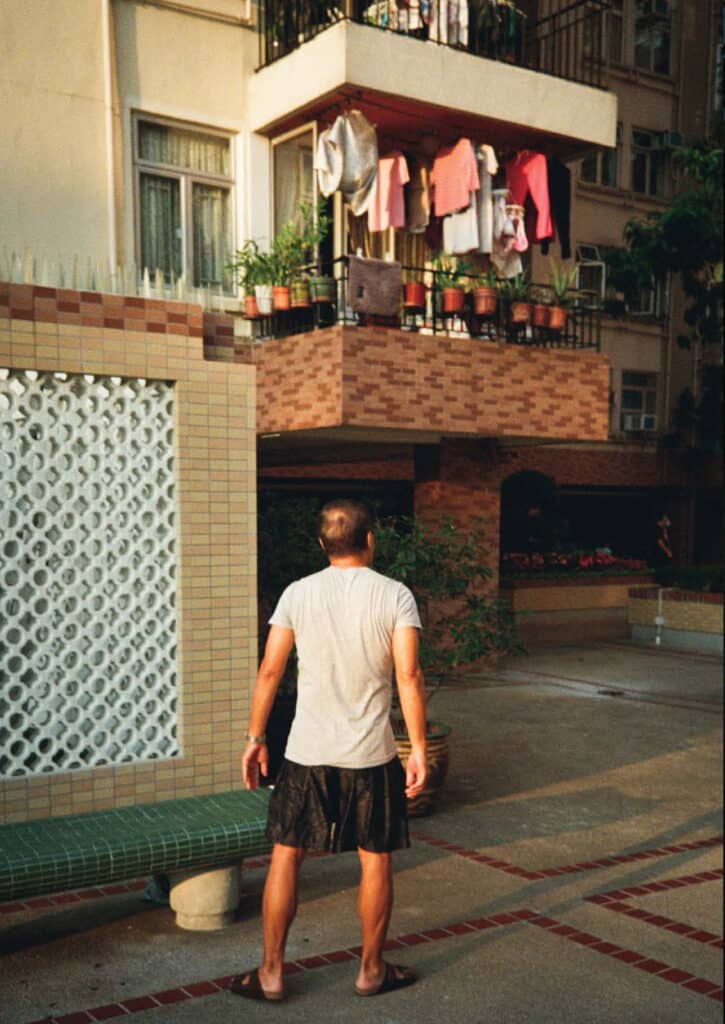

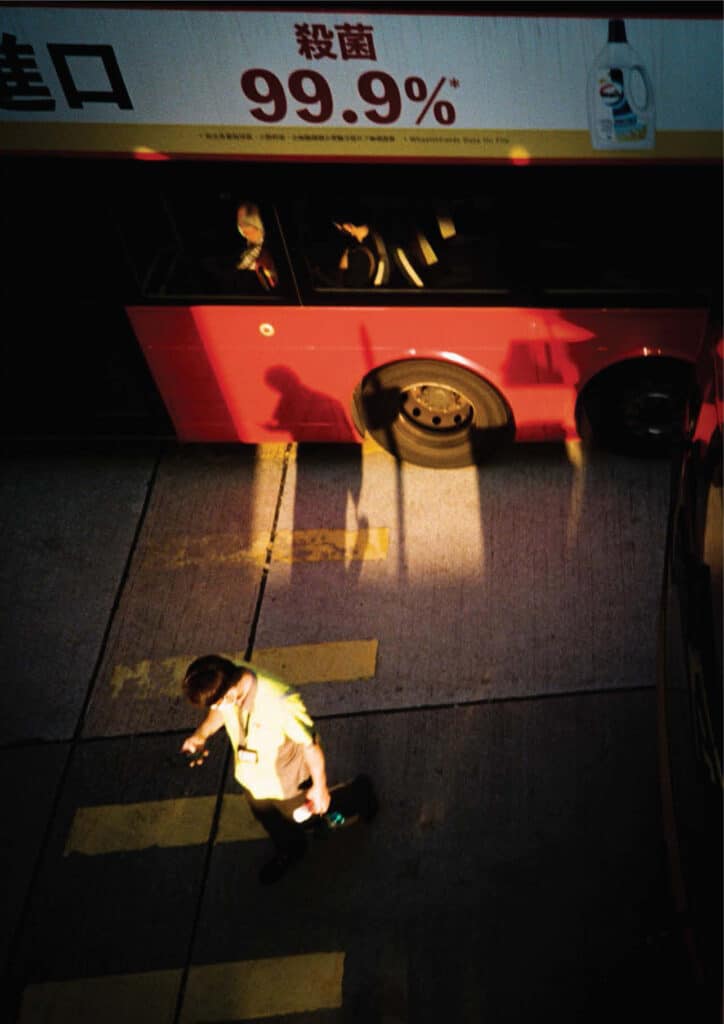

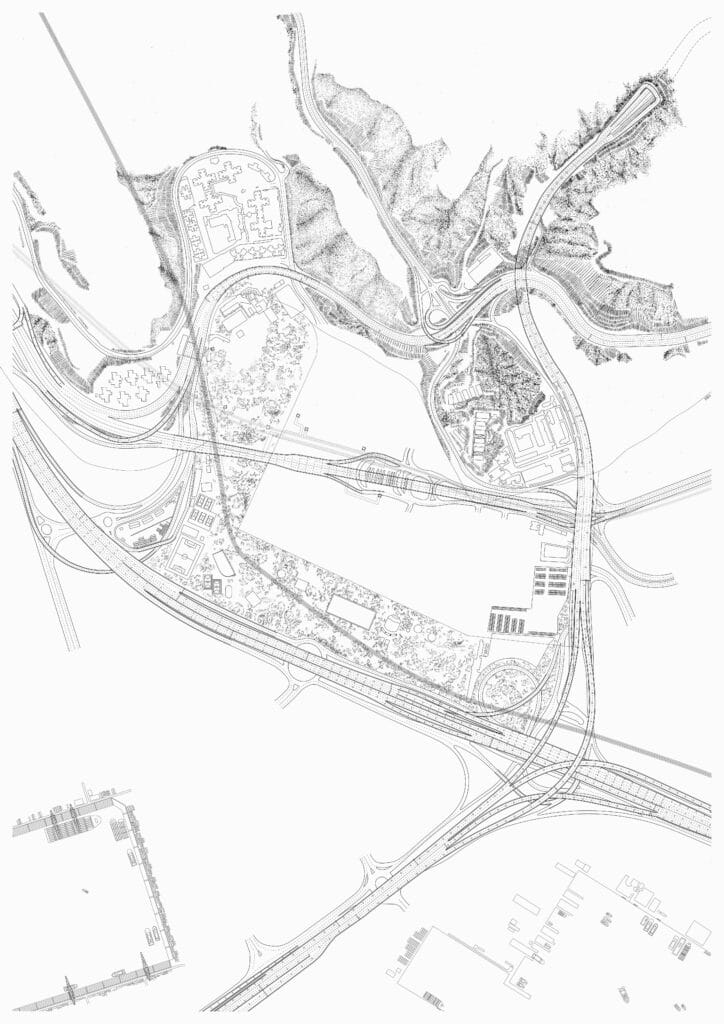

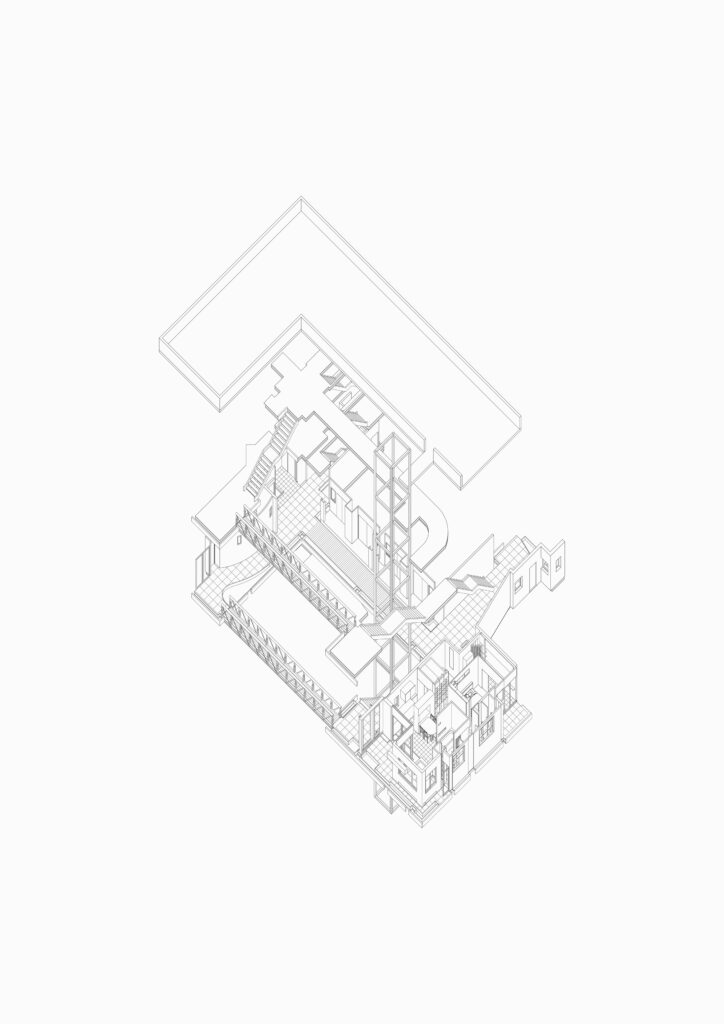

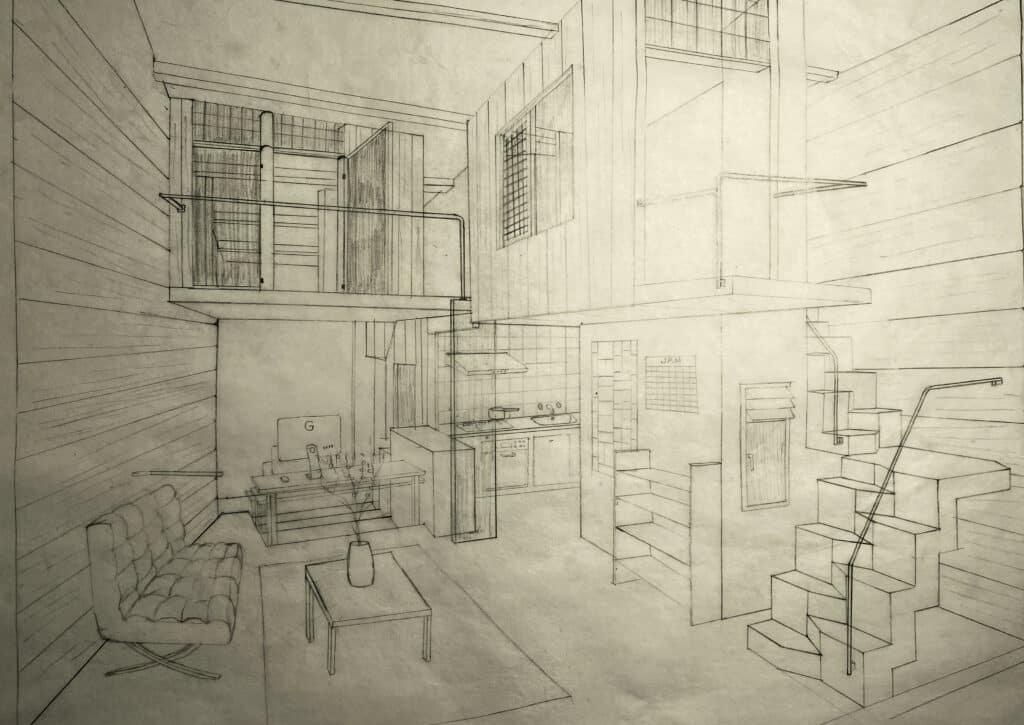

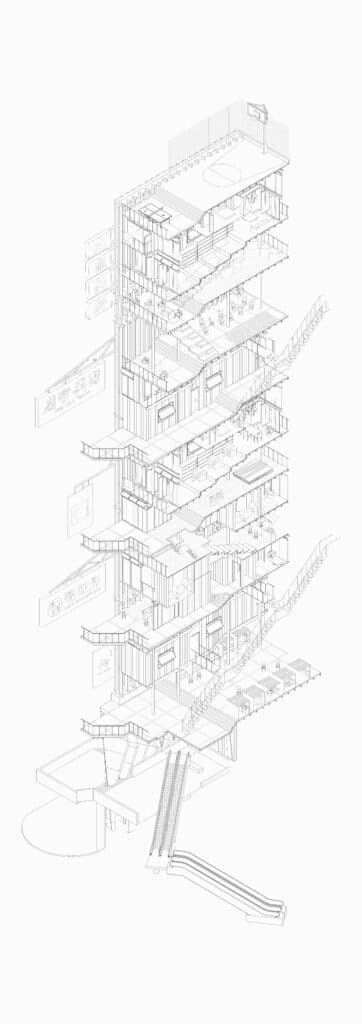

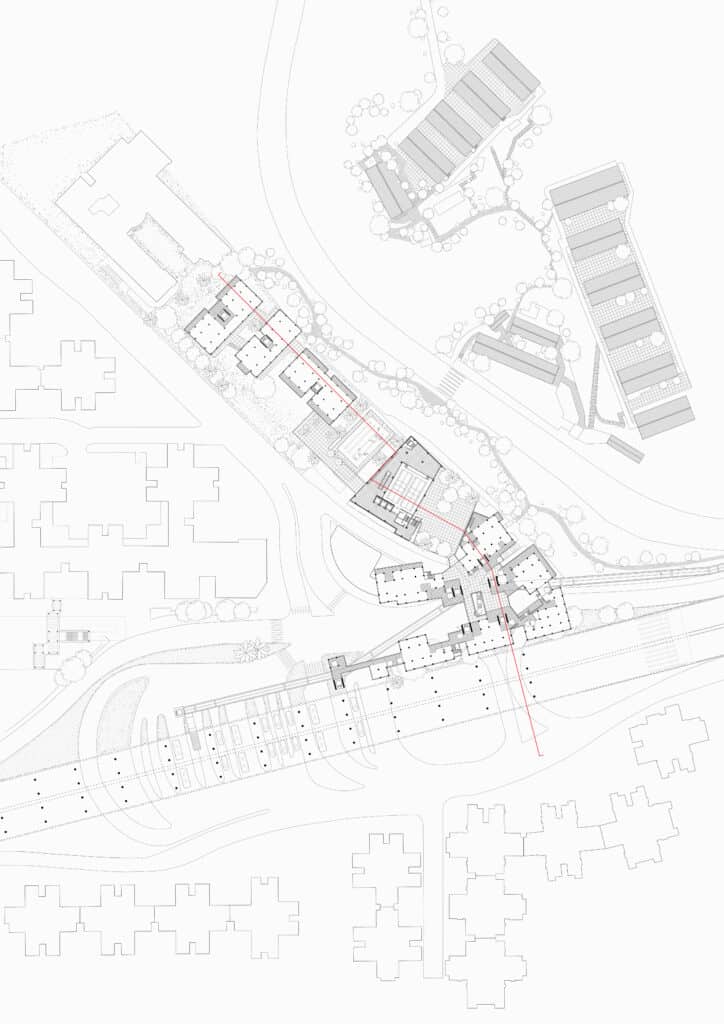

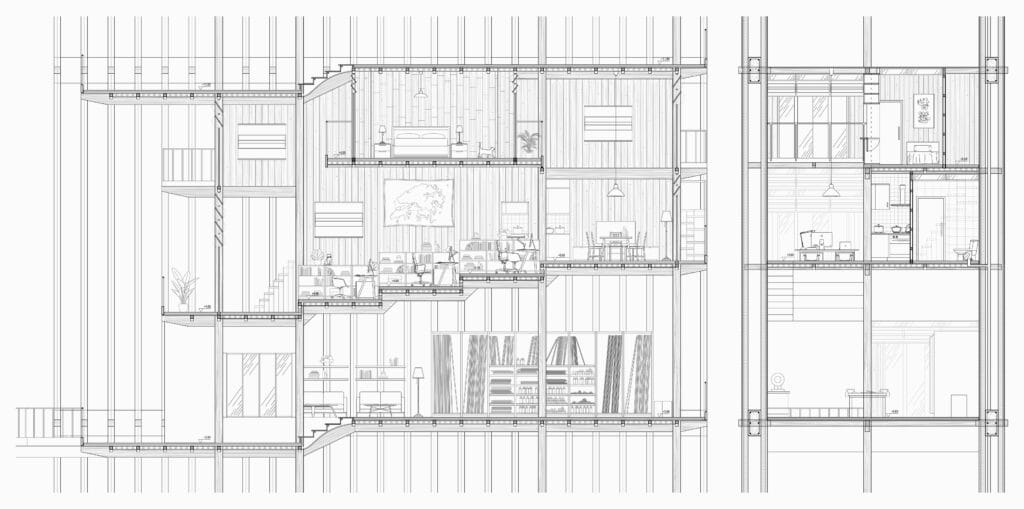

During spring 2020, the students realised that it was their responsibility to make the most of the singularity of the pandemic situation. The site for the studio was the Mei Foo Sun Chuen estate, which provided the platform for an inquiry into collectivity through the architectural problematics of housing. We used the specific circumstances of quarantine and distance to question the relationships between interior and exterior, both from an urban and a domestic perspective. We envisioned scales of collectivity and gradients of intimacy, considering housing as a collection of domestic fragments that were brought together around a narrative created by each student observer. Entrances, circulation and communal areas, were understood to be places that fostered invisible links within a community, creating opportunities for formal and informal encounters.

How can we think of an architecture that mixes together ways of living that, in the time of a pandemic, becomes a ‘threat’ to the domestic? How can we not fall prey to the interior as synonymous with an architecture of security? The Mei Foo estate deals simultaneously with both intimate domestic and a vast territorial scales through the repetition and variation of the single units. On the one hand it is an ‘urban landscape’, but it is also a collection of individual dwellings: ‘interior landscapes’. Mei Foo speaks to the importance of housing and the individual unit as a repeated element within a wider territory. The studio presupposed that the unit is the nucleus of the city. The intimacy of the interior and the urban are intertwined.

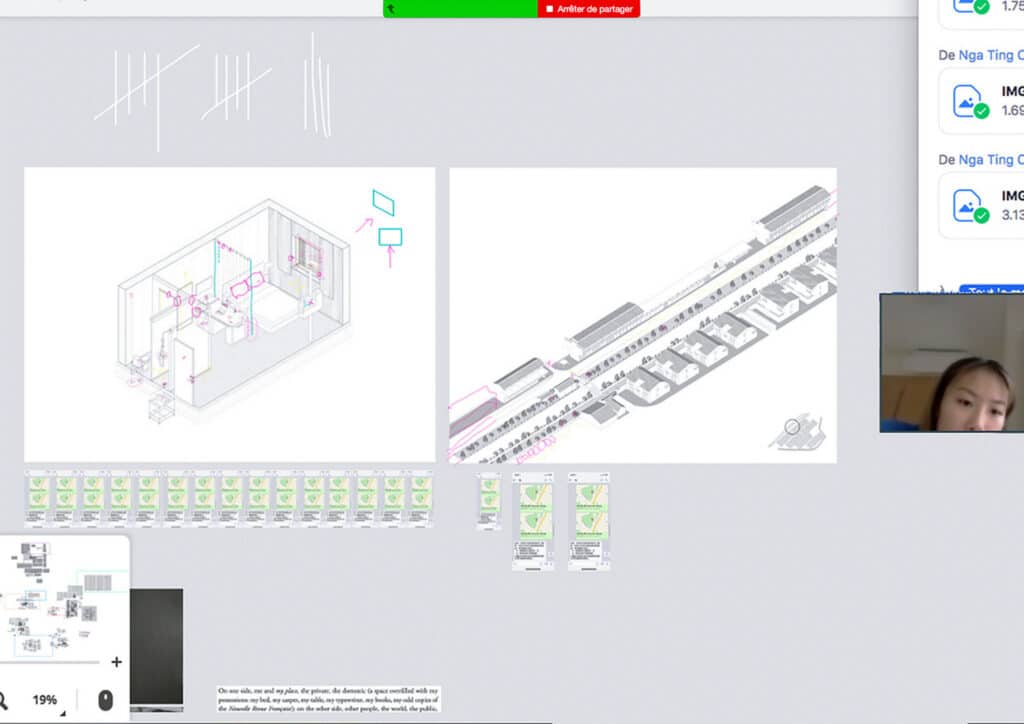

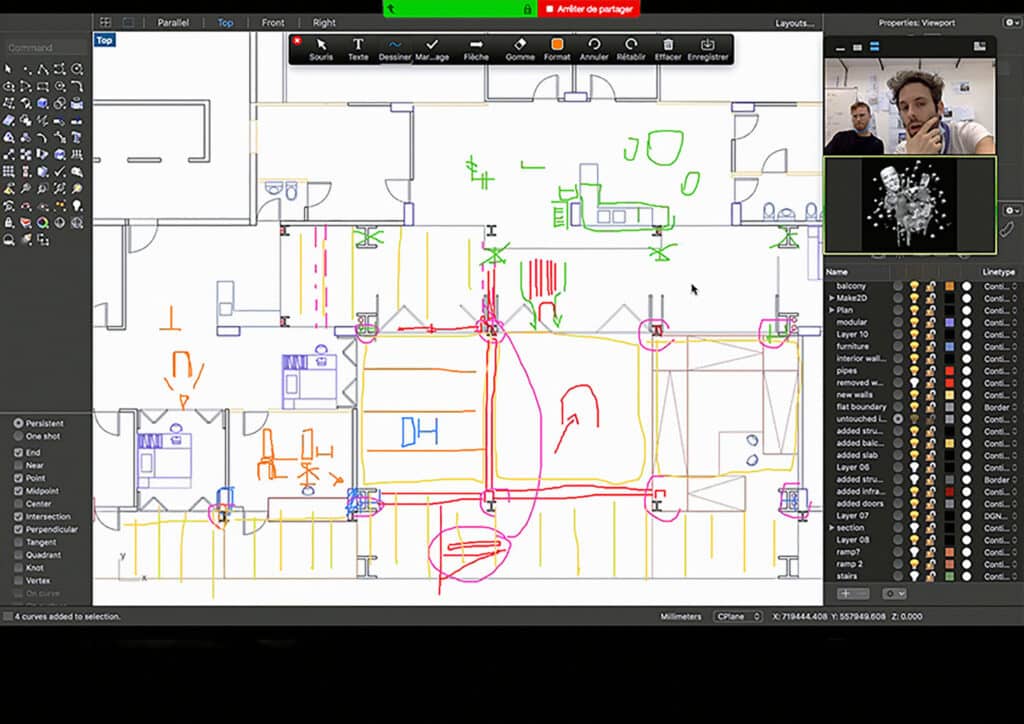

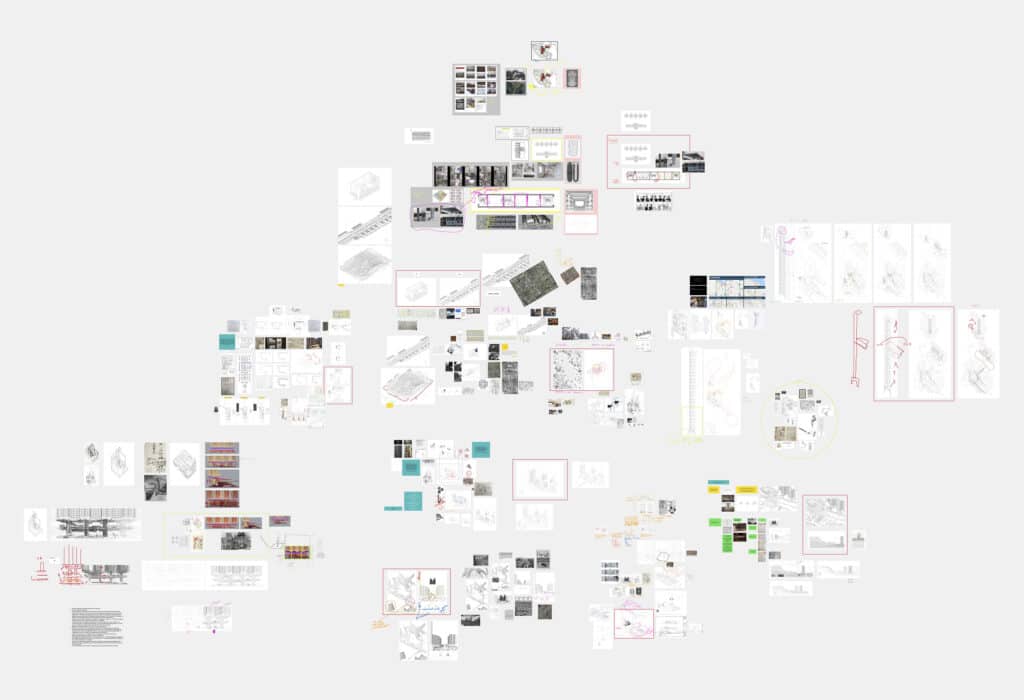

The introduction of Concept Board (conceptboard.com) – a digital display wall – as an alternative drawing tool provided the studio with some sense of group cohesion. Students were able to upload, annotate and discuss each other’s proposals. Moreover, Concept Board added an extra dimension to the conventional studio display wall: memory. It kept track of what had been posted several weeks before. On our wall, each ‘image’ is the bearer of a thought, a progression. Placing one’s drawings into space allows for collective reflection and a shared narration of the phenomenon. To draw is to construct a thought and a critical regard at a given situation.

For the studio to draw a phenomenon is not just to illustrate it or repeat it. Rather, drawing as a form of research puts forward the importance of assessing architecture through multiple scales beyond that of the building. The studio aimed to reveal the inherent capacity of the architect to think both as a maker and a territorial agent, thus triggering an awareness of the designer’s social and environmental responsibilities within the design process.

If the pandemic reinforces the idea of equality – anybody could be infected – confinement reinforces a feeling of injustice in the hearts of people, for its disparities.

Drawing allowed us to inhabit both our own condition and to project ourselves into others’. Drawing trains our analytical mind along with our imaginative one. Through this lens, constructing the drawing means constructing one’s empathy and relation to the world. Though, to connect the drawing of the extraordinary circumstances of quarantine with the ordinary circumstances of the Mei Foo estate reveals an inseparable relation within our collective human condition, which is the ongoing confrontation with the ‘other’. Were we ever as aware of the ‘other’ as we are now? Can we ever forget it?

The nature of this collective experience refuses abstraction and generalisation, but rather demands attention. To abstract tends to forget not only the body, but the body situated in space, the individualised body caught up in tangible relationships that are not interchangeable, and not relativizable in the last instance. Whereas, to draw attentively does not reduce the individual to a theoretical construct. To draw attentively is to measure specificities and engage with the concrete problems that a person faces as an individual living in a community of others.

Guillaume Othenin-Girard (MScArch, ETH) is an architect and an Assistant Professor of design at the Department of Architecture at the University of Hong Kong since January 2020. His research and teaching explore among other fields, the transformative role of drawing in investigations of the relationship between territory and architecture.

Students

Nga Ting Cheung, Yi Go, Ka Chun Lai, Hin Fung Sherman Lam, Jennifer Cheuk Wing Lam, Ruoxi Li, Yin Li, Kent Mundle, Xiao Tang, Ka Lee Tsang, Long Ting Yu, Rochelle Charis Yu.

Teaching Assistant

Kent Mundle

Research Assistants

Jingxi Cen, Hoi Ming Du

– Fabrizio Gallanti, Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample