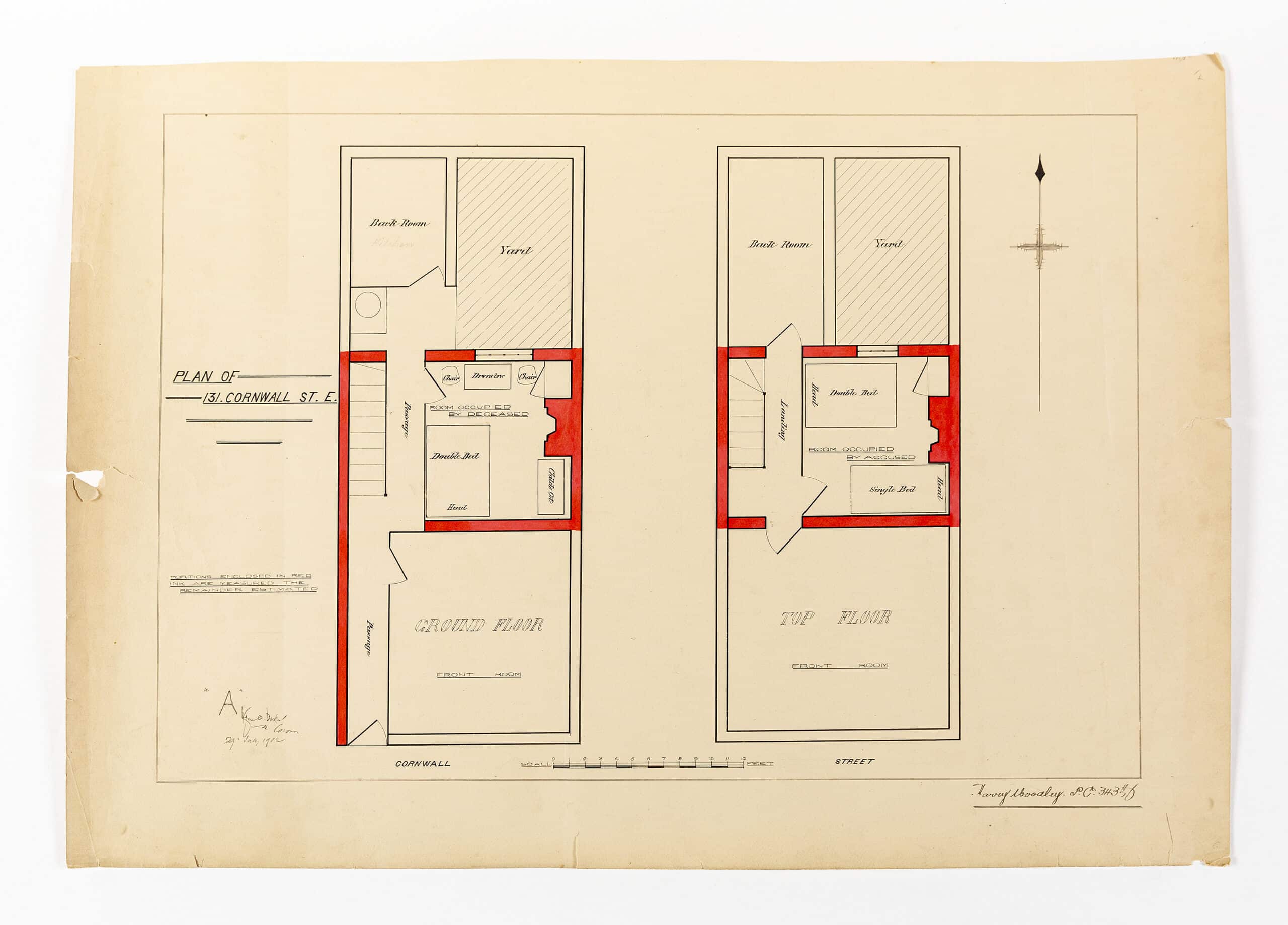

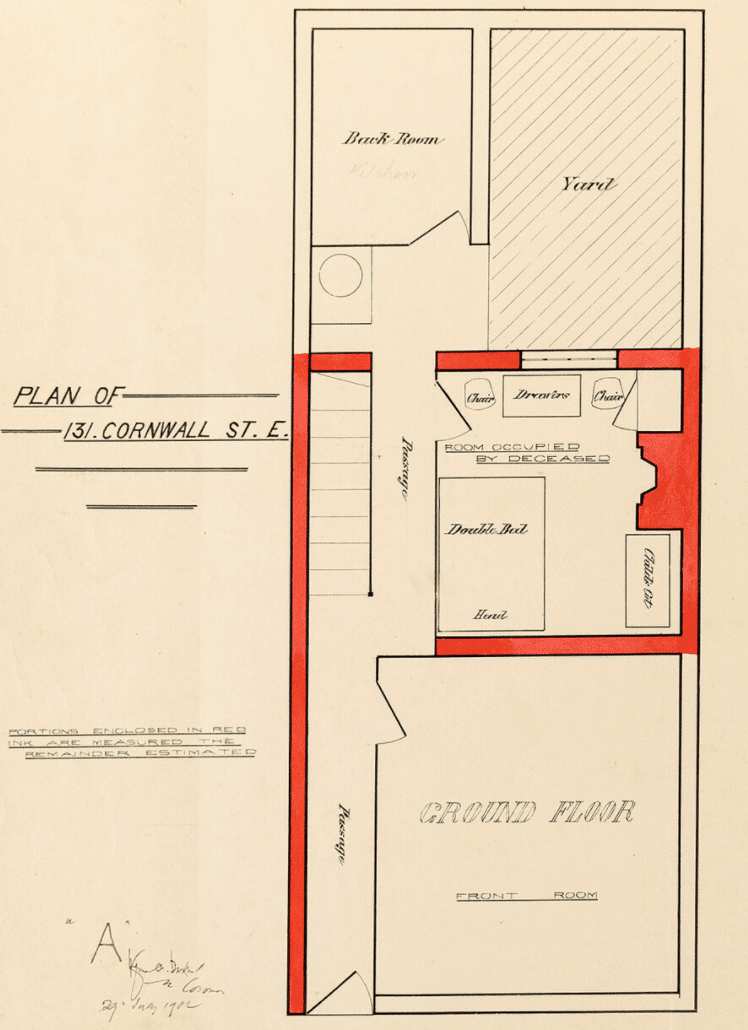

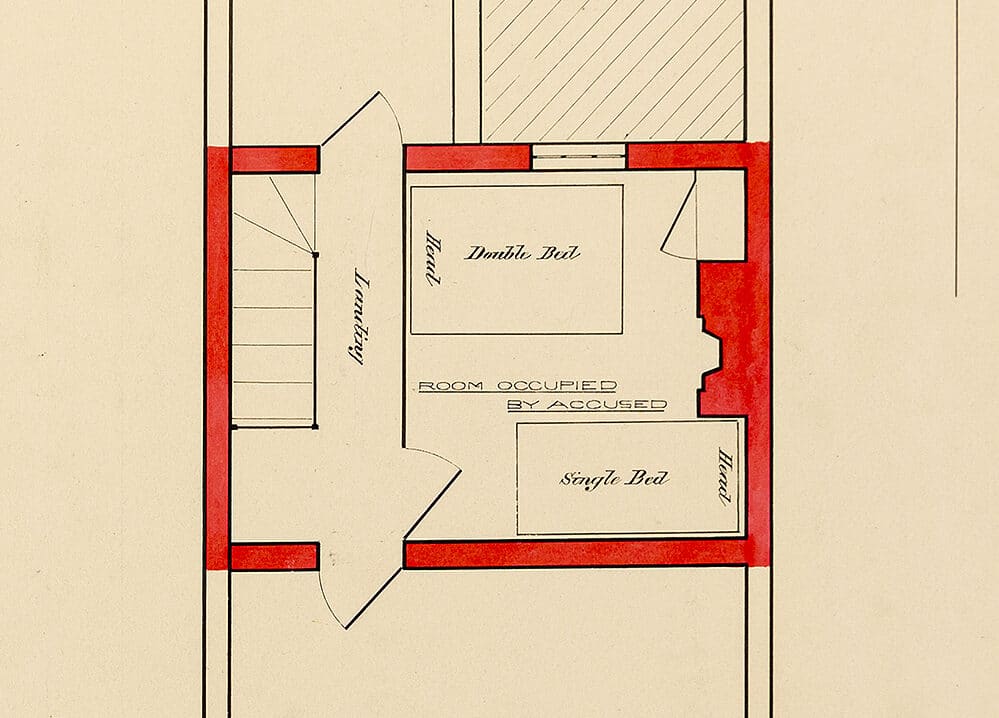

PC Harry Woodley: Plans of No 131 Cornwall Street, 1902

Extracted from Stories from Architecture: Behind the Lines at Drawing Matter by Philippa Lewis, published by MIT Press © 2021. Preorder the book here.

The drawings around which Stories from Architecture are written are all part of the Drawing Matter collection. Some of the texts were first published as ‘Behind the Lines’.

It was a short walk from Shadwell police station: right into David Lane, left into Cable Street, right into Dean Street, and up to Cornwall Street, which was overshadowed by soot-black railway arches and gloomy even on that scorching July day. PC Harry Woodley ran his finger round the collar of his serge tunic, which was sticking unpleasantly to his neck, and scanned the terrace to see where No 131 might be. Women sat on the doorsteps of the old two-up, two-down houses, gossiping, staring vacantly into space, or eyeing up potential customers. Doorways gaped open in the vain hope of ventilating the overcrowded interiors; some had boards propped across the bottom to prevent the smallest children from running out into the street. Older children, ragged, hatless and sometimes shoeless, muddled around in the dirt. The air was fetid. A very few of the houses shone out as beacons of respectability, with clean, curtained windows and ornaments on the windowsill – a plant pot, or wax fruit and flowers displayed under a glass dome. Mostly, however, it was a scene of broken windows and brooding despair; all too familiar.

PC Woodley often tried to imagine what the houses on his beat would have looked like when new – not particularly well built, but tidy and homely and not, as now, stuffed to the roof, oozing with people. For the past couple of decades London had been flooded – was still being flooded – with people desperate for somewhere to live, even if it was a small single room costing six or seven shillings a week. He recognised that he was also part of that flood; he was born in Essex, his wife Mary in Berkshire. He thought of his own lodgings at 11 Parfett Street up in Whitechapel. Four floors, though the basement was hardly fit for human habitation, and four households, with not a single native Londoner: the cabinetmaker, Judah Charmskis, recently arrived from Minsk with his family; the capmaker, Morris Shaer, from somewhere else in Russia, with a wife from Germany; and the district nurse, Emily Burke, from Clifton in Somerset, who shared a room with her sick friend, Alice Warren, from Sheerness in Kent. He often wondered how the people in No 10 managed. When he’d chatted to the census enumerator the previous year he’d found out that no less than thirty-four people lived there, most of them from Russia and Poland, with twelve children under ten. How did they stay sane?

The door of No 131 was opened by a woman who said her name was Ann Harris, quickly adding that she lodged with her husband, niece, and children in the front room on the first floor. She seemed anxious when she saw his uniform, but PC Woodley explained that he had come to draw plans of the rooms where Mrs. Smith had died, and where William Brake, the man accused of killing her, lodged. They were ‘required for the trial at the Old Bailey, by order of the Coroner’.

His statement was met with a tearful outpouring verging on the hysterical. She’d only been living here for eight weeks and now this. She’d been drinking in the Railway Arms just the night before with Mrs. Smith – ‘Mog’, as everyone called her – and then she went and got murdered. She’d seen Brake’s knife. She’d seen him cut his tobacco with it. She’d seen the body. She’d seen the blood.

PC Woodley nodded sympathetically and stepped into the house. Briefed by the Detective Sergeant back at the station, he made straight for the back room on the ground floor and shut the door against Ann Harris and her wailings. He measured it carefully: 9 ft. by 10 ft. He had read the statement given by Margaret Smith’s daughter, Alice, who lived nearby in Sage Street, and knew that Alice’s children, five-year-old Maude and three-year-old Henry, slept with Margaret in the double bed, as did Alice’s sister, Ellen – all of them lying head to toe, like sardines in a tin. Why did Alice farm her children out to her mother every night? He guessed, sighed, and thought of his precious only child, little Elsie, safely at home with Mary.

He did a rough sketch of where the furniture was in preparation for the proper plan that he would draw back at the station; the quiet hours spent concentrating on lines, lettering, and colouring offered a welcome escape from his usual duties. PC Woodley sometimes wondered about the usefulness of the plans he made – perhaps, without them, members of the jury would not be able to conceive of living in such small overcrowded rooms. When he’d finished he was always struck by how neat and impersonal they appeared, completely belying the mayhem that had taken place.

The vision of Margaret Smith lying stabbed and bleeding on the floor while her grandchildren slept in the bed was horrific. He thought again of Elsie and quickly left the room, wondering if he would ever become inured to death and violence. PC Woodley was all too familiar with the tensions of living cheek by jowl, in poverty. Bad blood between lodgers, drunken husbands, careless infidelities, cat fights, thievery, debts, prostitution – he’d seen it all.

Moving upstairs, to where William Brake had lived, he walked into a crammed room that was identical to the one below – except for the disheveled figure who lay snoring on one of its two beds. This turned out to be Margaret Smith’s brother, Charles McCarthy, who’d been lodging in the room with Brake for the past fortnight. McCarthy groggily explained that he was a stevedore down at Shadwell Basin, but work was thin on the ground because the big ships couldn’t get into the docks any more. There had been no work for two days, so he’d be off to the public house shortly – the publican would give him a sub. But why that bastard Brake had killed his sister was a mystery to him. The two of them had been ever so friendly in the kitchen the night before. Mind you, Brake was usually half-drunk. He’d said he was going to sign on as a boatswain to a new ship that morning. Why hadn’t he? Then they wouldn’t have seen him for six weeks or more.

Harry had signed the temperance pledge some years before, but there had been a time during his twenties when he was rarely out of the public house. He knew their appeal only too well: anything to get out of a dismal home for a bit of cheer. You couldn’t avoid them – he could think of five in Cable Street alone. But drink made many men violent – women, too, come to that. Cuts, bruises, and black eyes were frequent sights, though stabbing to death was something else. Thank the Lord, he thought, for his steady job as a policeman. The pay was low and the shifts long, but he’d reached the ripe old age of forty-one and in less than ten years he had his police pension to look forward to. He and Mary planned to go back and live in the countryside.

Reckoning he was finished, he went downstairs. Ann Harris emerged from the kitchen at the back of the house. Would Brake swing for murder, she wanted to know, and added that if he wanted her opinion he’d killed Mog because he owed her money. Harry Woodley was non-committal, but to change the subject he asked who else lived in the house. Apparently, the front room on the ground floor had been empty for a few days and George, Mog’s son, lived in the back room upstairs.

‘Such a nice lad, just back from fighting in South Africa. I tell you he had some horror stories. He said that the camps where they’ve interned all the Boers make Cornwall Street look like Buckingham Palace. Up to ten people – women, children, old men unfit for service – herded into a single tent in the dreadful heat, with scant rations. They’re all falling sick and dying. At least here we’re not starving to death. Well, not really. Poor George, he had to help the doctor move the body. And little Ellen, called back from her cotton spinning all of a sudden – she’d left for work before this hall happened. She and George both’.

PC Woodley felt a sudden need to get out of the house and made for the open door. Brake had confessed his crime, so the jury would find him guilty. It seemed to him a clear case of murder, in which case he would hang. If it turned out to be man-slaughter, he would be in for years of penal servitude with all the flogging and hard labor that entailed. Whichever, he deserved it.

Notes

Harry Woodley joined the Metropolitan Police Force on April 13th, 1885 and left on August 15th, 1910. His last posting was to H Division (Whitechapel) as a Police Constable, during which time he was tasked with making crime scene plans for Old Bailey trials (National Archives MEPO 4/343/199).

The full transcript of William Brake’s trial can be found at oldbaileyonline.org (reference number t19020909-582). It took place on September 9th, 1902 and he was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to twelve years’ penal servitude.

The 1901 Census, available at censusonline.com, has the information on Harry Woodley’s lodgings at 11 Parfett Street as well as for 131 Cornwall Street. Charles Booth’s Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People in London, undertaken between 1886 and 1903, was an exhaustive survey of working-class life.

The original notes and data are held at the London School of Economics (reference Booth/ B/25). George Duckworth (Virginia Woolf’s stepbrother) walked around the Cornwall Street area in the company of Inspector Drew, District 8, Aldgate, St. George’s in the East, Shadwell on February 1st, 1898, and made notes on the state of the housing and its inhabitants on pp. 182–191 of his notebook. ‘The Maps Descriptive of London Poverty’ were part of Charles Booth’s Inquiry. An early example of social cartography, each street is colored to indicate the income and social class of its inhabitants. Part of Cornwall Street is black – ‘Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal’, the remainder is dark blue – ‘Very poor, casual, chronic want’. There is a very small amount of light blue at the western end of the street – ‘Poor. 18–21 shillings per week’. Parfett Street, where Harry Woodley lived, was principally colored purple – ‘Mixed, some comfortable, some poor’.

The 1890 Police Act granted policemen pensions after twenty-five years’ service and also introduced pensions and gratuities for widows and children of policemen. In 1901 the starting salary for Metropolitan police constables was raised to 25s. 6d. a week.

Emily Hobhouse’s ‘Report of a Visit to the Camps of Women and Children in the Cape and Orange River Colonies’ was delivered to the British government in June 1901.