Brunswick Centre

It is a truism that aggressive building contractors treat architectural drawings with contempt; McAlpine’s were no exception and it being my temporary responsibility in 1969 to negotiate a procedure of actually constructing the visible fair faced in-situ concrete of this vast structure, I arrived at The Brunswick’s site office ready for a dressing down. And I got it, with their project manager berating me with his ‘riot act’ and throwing our meticulously accurate drawings around his wretched little site office with abandon. However, I did notice that these otherwise contemptible sheets had been carefully marked-up and this gave me the one advantage I needed in a difficult confrontation. Pushed as to ‘Exactly what do you expect us to do with these – these pretty pictures?!’ I replied that all we wanted was for McAlpine’s to build the in-situ concrete as accurately as it has been drawn. This brought on an almost apoplectic rage; but this guy knew he was beaten. Unfortunately for McAlpine’s, Patrick and his small team of assistant architects had so carefully documented this very radical building that it was cheaper to build it as documented than to start again with a conventional in-house design!

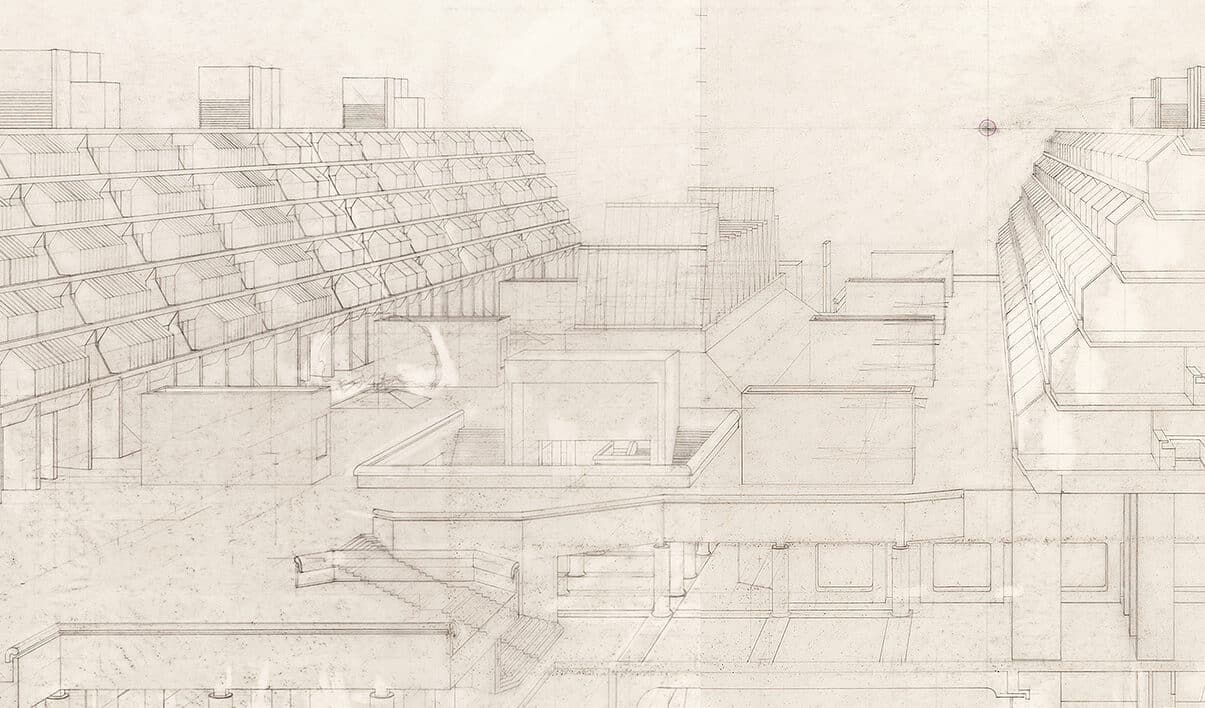

All of this had entailed us in the best part of two years of intense studies of how best to articulate The Brunswick’s in-situ concrete structure. Of course, those ranges of cream stuccoed terraces at Regent’s Park were Patrick’s template, but translating Nash’s refined urbanity into painted in-situ concrete adjoining Coram’s Fields was fraught with possible shortcomings. Patrick somewhat diffidently proposed a system of almost Cyclopean grooves to be cast into the concrete as each stage was poured: and despite the obvious shortcomings of introducing fragile timber fillets into brutally manhandled, fair-faced concrete formwork, Patrick stuck to this idea: his own very personal rebuttal of Reyner Banham’s Brutalist imperatives. Consequently, a set of very accurate groove-setting-out drawings were required and I prepared these over many months: these numerous large external elevations and sections of the entire project imperceptibly tightened Patrick’s overall design and by the time McAlpine’s finally terminated Patrick’s commission it was already too late for them to do anything but build The Brunswick as drawn.

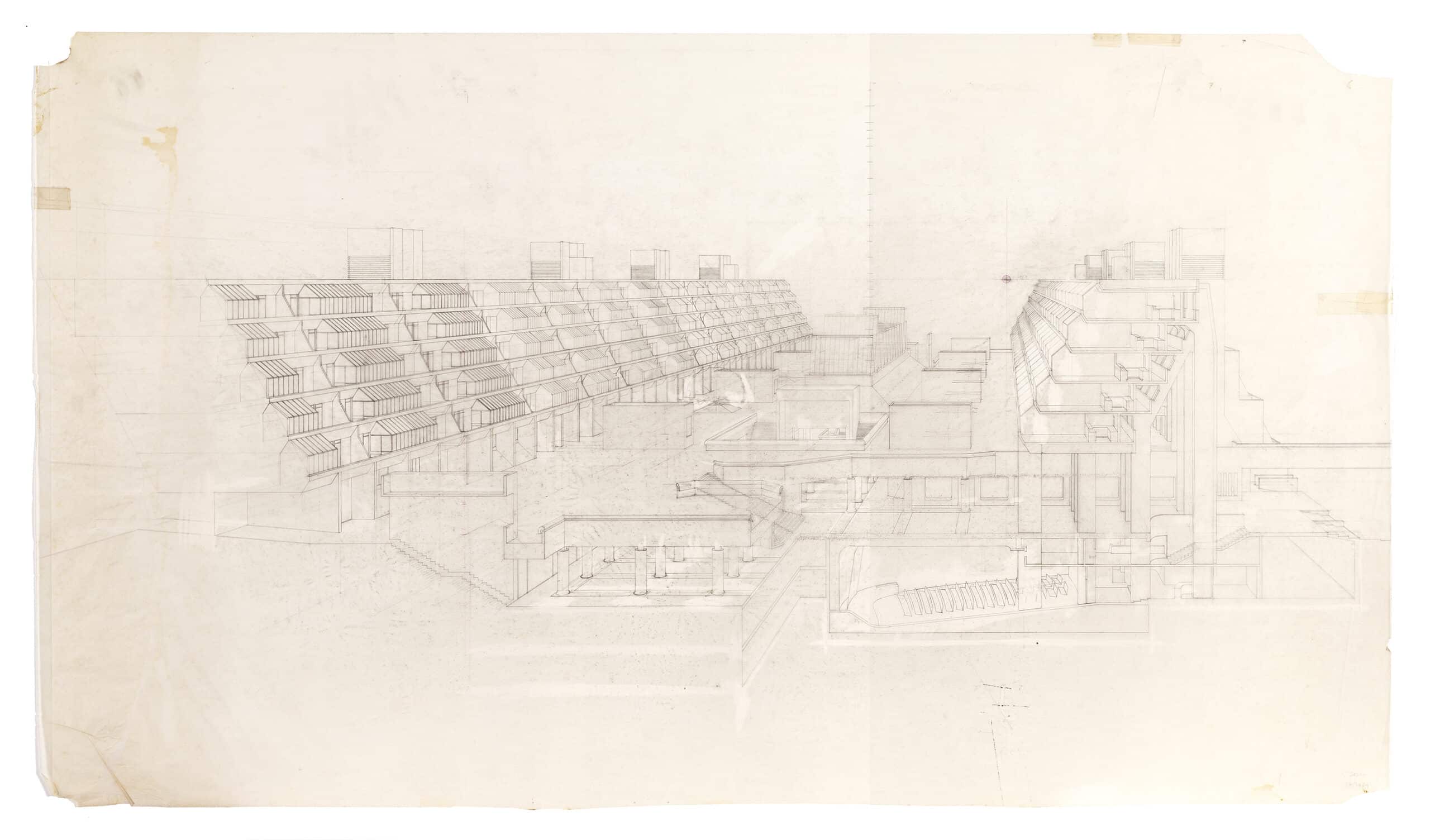

In early autumn 1969 and as the end of his engagement loomed, Patrick one morning announced that he would now write an account of his great project and for this he would certainly need a fountain pen and hurriedly left the office, soon returning with a brand new black, gold-capped British Parker ‘51’ and a large bottle of their blue ink (really quite strategic, as blue script at that time could not be photocopied). Patrick, by now back sitting at his austere late eighteenth-century round table and faced with his new pen, ink and a stack of quarto sheets, asked if I would now care to draw a very large perspective of The Brunswick as it was intended to be when completed, to accompany his forthcoming text.

Here the accessible complexity of 1960s London comes to the fore. On depositing my monthly salary at the ANZ Bank in Cornhill (and where a cheque drawn on Messrs Coutts was invariably noted) an extended lunch break also allowed for a brief visit to the BM’s Print Room and a few minutes viewing the print-sellers Craddock & Barnard’s always changing window. On one of these outings I first encountered Canaletto’s wonderful 1741 etching, ‘The House with the Peristyle,’ with its inclusive intimacy achieved by this master’s deceptively simple device of lifting the horizon to just above the pediment and just below the roof line. Here Canaletto draws us into his busy vernacular foreground beneath a ruinous peristylar tenement while also balancing our gaze with a distant capriccio of Venetian monuments (inevitably, now a rare and expensive print: wish I had got one when they were still remotely obtainable).

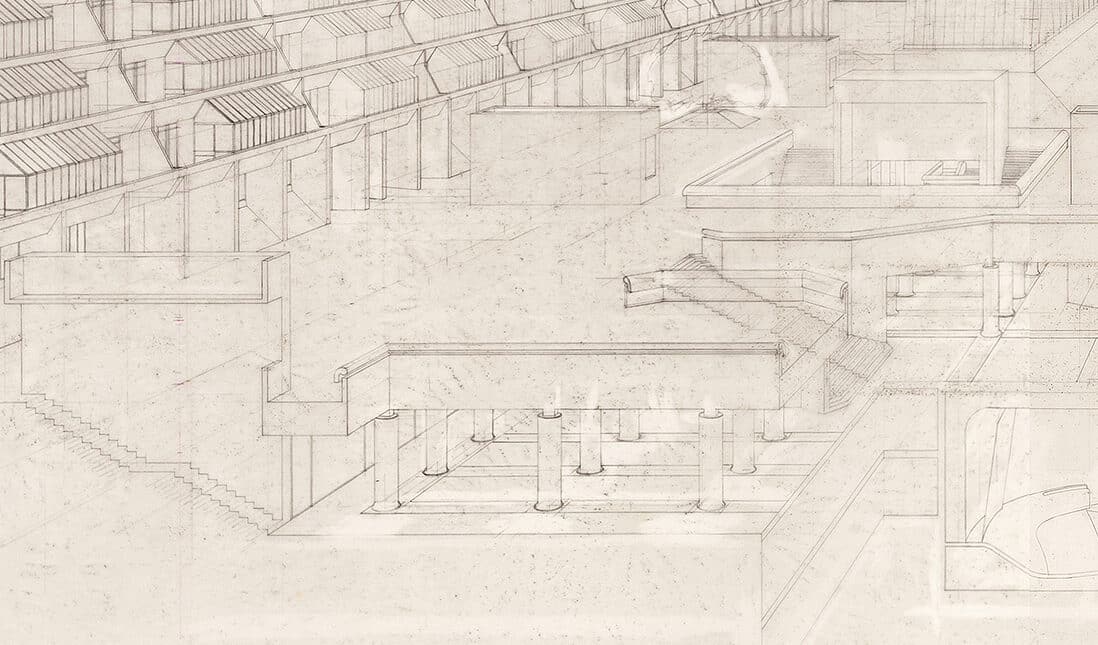

Emboldened, I now set up a pencil esquisse (now almost certainly lost) and Patrick immediately grasped the potential of such a juxtaposition: where a detailed cross-sectional perspective through his elegiac portico facing onto Coram’s Fields and shown well below an elevated horizon at the roof line of the paired internal gradins also allowed for a legible overall rendering of the civic inclusiveness of the whole assembly: here was the possibility of an intriguing drawing of an only-just-forty-years-old Patrick Hodgkinson’s radically new urban ‘Type Specimen’(and so far, far beyond either Sant’ Elia or Chiattone!). Of course, none of this was to be in the pompous manner of Le Corbusier who, once the galley-slaves had mechanically set up his huge perspectives, then traced them off freehand for publication replete with wayward biplanes and expensive cabriolets.

K.F. Schinkel was however much discussed, particularly the austere engraved plates of Charlottenhof and the Altes Museum in his immortal Sammlung and in which, significantly, Schinkel’s dramatic perspectives also employ intentionally modified horizons similar to those of Canaletto.

Meanwhile our author wrote on and on with remarkable surety, seldom crumpling a sheet and always turning all completed pages face-down on leaving his round table. Intermittently, Patrick would bring his chair over and sit silently observing as my full size draft emerged from the myriad of construction lines needed to proportionally adjust scaled working drawings into any type of perspective system, and as this was not a projective drawing made in accordance with a traditional method (such as Pozzo’s) much patient sighting well back from my drawing bench was needed before we could both confirm the intuitive rightness or otherwise of this by now five-foot-long pencil drawing as each stage was set down.

One morning, Patrick produced an engraved plan of Montpazier by J.H. le Keux which he had carefully photographed from an old journal. So, here was the actual archetype of The Brunswick, Montpazier, a remote mediaeval bastide in south-western France? However, what is so compelling here is that Patrick brings forward an idealised town plan drawn in the nineteenth century and far removed from the actual Montpazier that he had many times visited (and even extensively photographed with a bellows field camera and tripod during AA vacations). This is as final a proof as I can submit in defence of The Brunswick as being the very English conception of a very English architect (and, Montpazier was commenced by Edward I in 1285!). Now, does setting aside Banham’s ex cathedraattribution to Sant’ Elia et al, really seem so improbable? Small wonder that, on our scooting along one afternoon in the Aston (a dark blue DB3 DHC) somewhere near the AR’s offices in SW1, Patrick exclaimed, ‘Look, there’s Peter Banham crossing the street: and to think I could have hit him had I seen him sooner!’

With the draft of my perspective now completed, it only remained to trace it off onto a large sheet of matt surface plastic drafting media: this was done as carefully as possible so as to avoid the accretion of smudging which bedevils this so-called wonder material. Actually, it would have been much better traced onto that extremely fine Finnish detail paper that Utzon always insisted on and Patrick also knew of from his time in Aalto’s studio as an assistant on the Helsinki Pension Bank project: it is perfectly stable and it photographs much better. The whereabouts of my original are not presently known: what we do have here is this January 1970 archival print (very likely unique) plus my now somewhat battered pencil draft on good old-fashioned tracing paper.

Patrick, with his commission now much reduced by McAlpine’s and with nothing definite in the offing, gradually closed down his office at 32 Porchester Terrace W2 and in early 1970 I returned overland to Australia and an uncertain future as a solo architect in an anything but ‘mass society’. Just before I left London, we went to lunch at a crowded old fish cafe in an alley near Drury Lane: here only one dish was offered, a completely delicious large oval plate of boiled turbot and lobster sauce served with just one wine, a modest but excellent Riesling. The ancient bubble-glass windows were steaming up and the waitresses were pretty quick; and all this for only three quid a head!