PostDigital Collage: Naivety as an Ideo-aesthetic Technique

It was 2005, a moment of crescent belief in technical progress and modernity prior to the upcoming financial crisis that took place two years later. The early 2000s saw the progressive implementation of photorealistic modes of architectural representation through which firms were able to intensify the instrumentalisation of spatial design. Perspective renderings were identified with business and profit—neoliberal postulates—and characteristics such as smoothness, glossiness or high resolution represented notions of reliability and exclusivity. Drawing, then, supposed a direct anticipation of spatial experience, a guarantee that allowed observers to understand straightforwardly what was going to happen next. As if it were any other commodity in the market, realism intended to clarify for prospective clients what to expect from architects with little room for interpretation.

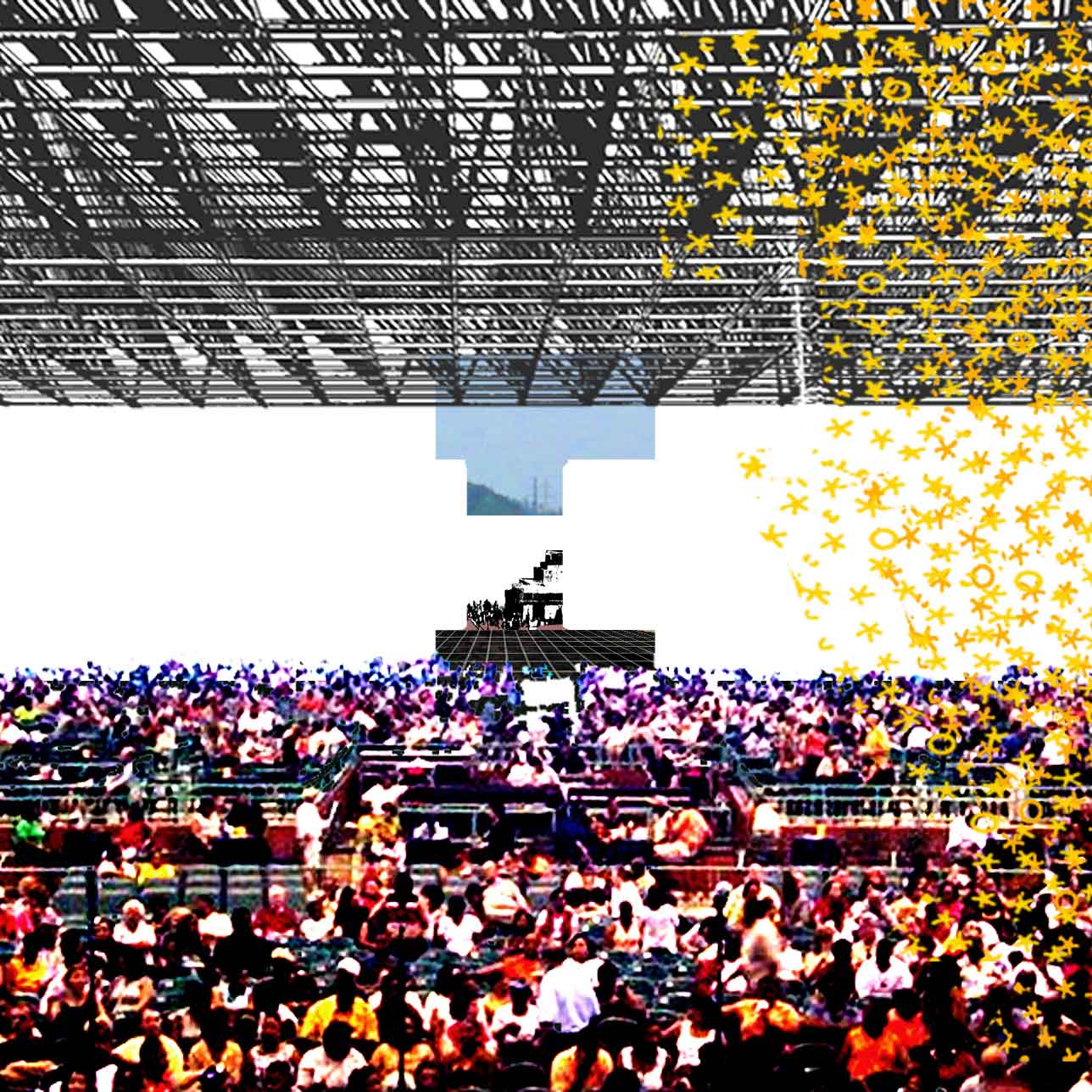

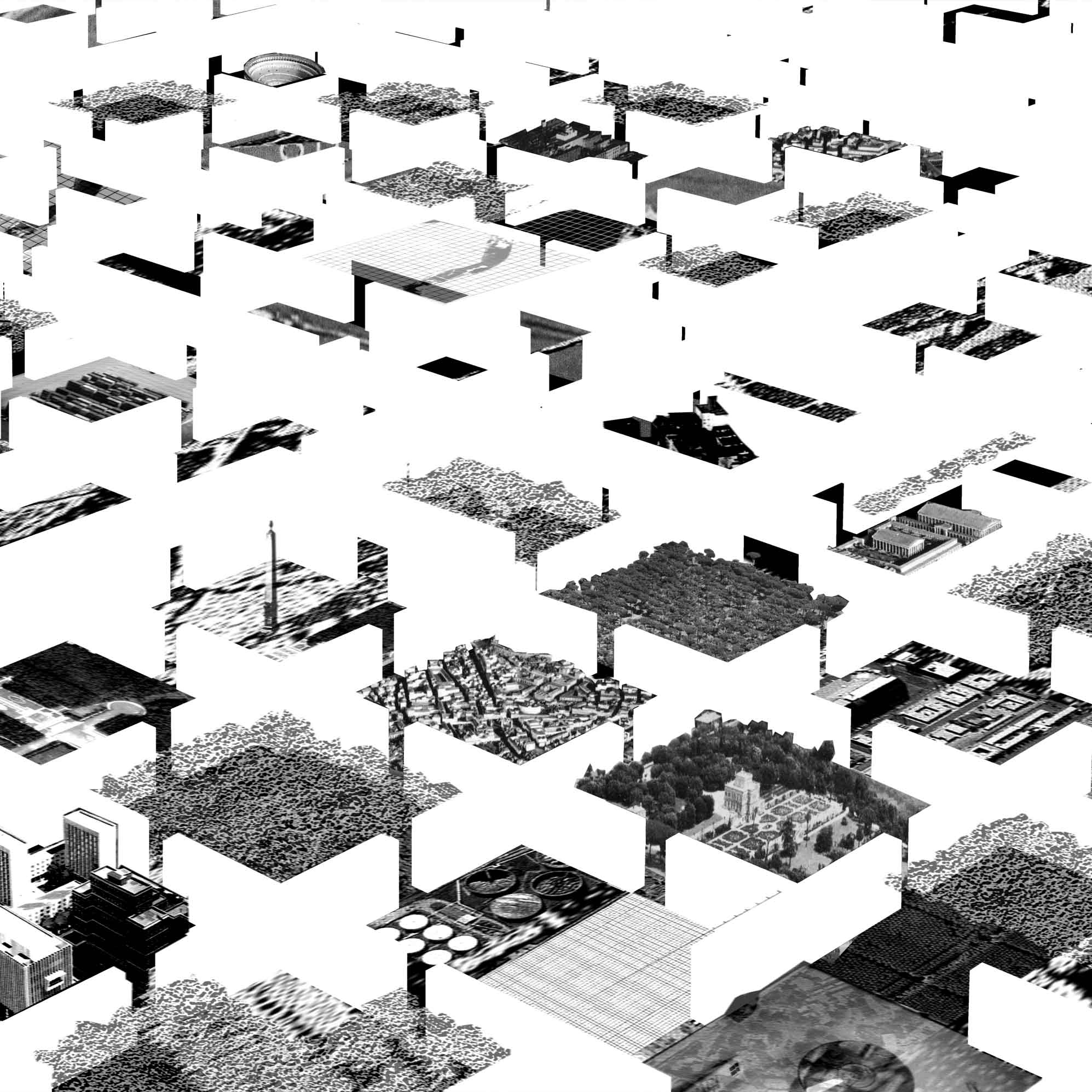

Within this context, the role of drawing as experimentation, as an open act of abstract composition and representation of ideas was losing its space. PostDigital collage, as first labelled by Sam Jacob, disrupted the line of technological progress in a quest for a visual chunkiness that recovered the mechanical assembly of readymade pieces—the analogue collage—as a valid compositional method.[1] At technological levels, the emergence of PostDigital collage identifies a change of paradigm through the adaptation of cut and paste logics to the digital environment. How did it happen? The advent of an image-based society through social media and global image repositories made available an unprecedented amount of graphic information. Visual overabundance linked with the proliferation of software such as Adobe Photoshop allowed users to quickly obtain images and the editing of fragments enabled the transition from cut and paste to CTRL-X, CTRL-V and edit. The reintroduction of flatness suggested an unexpected technological shift from realism to abstraction that opened the way for mechanisms of citation and intertextuality that contrasted with the dominant continuity and depth of renderings.

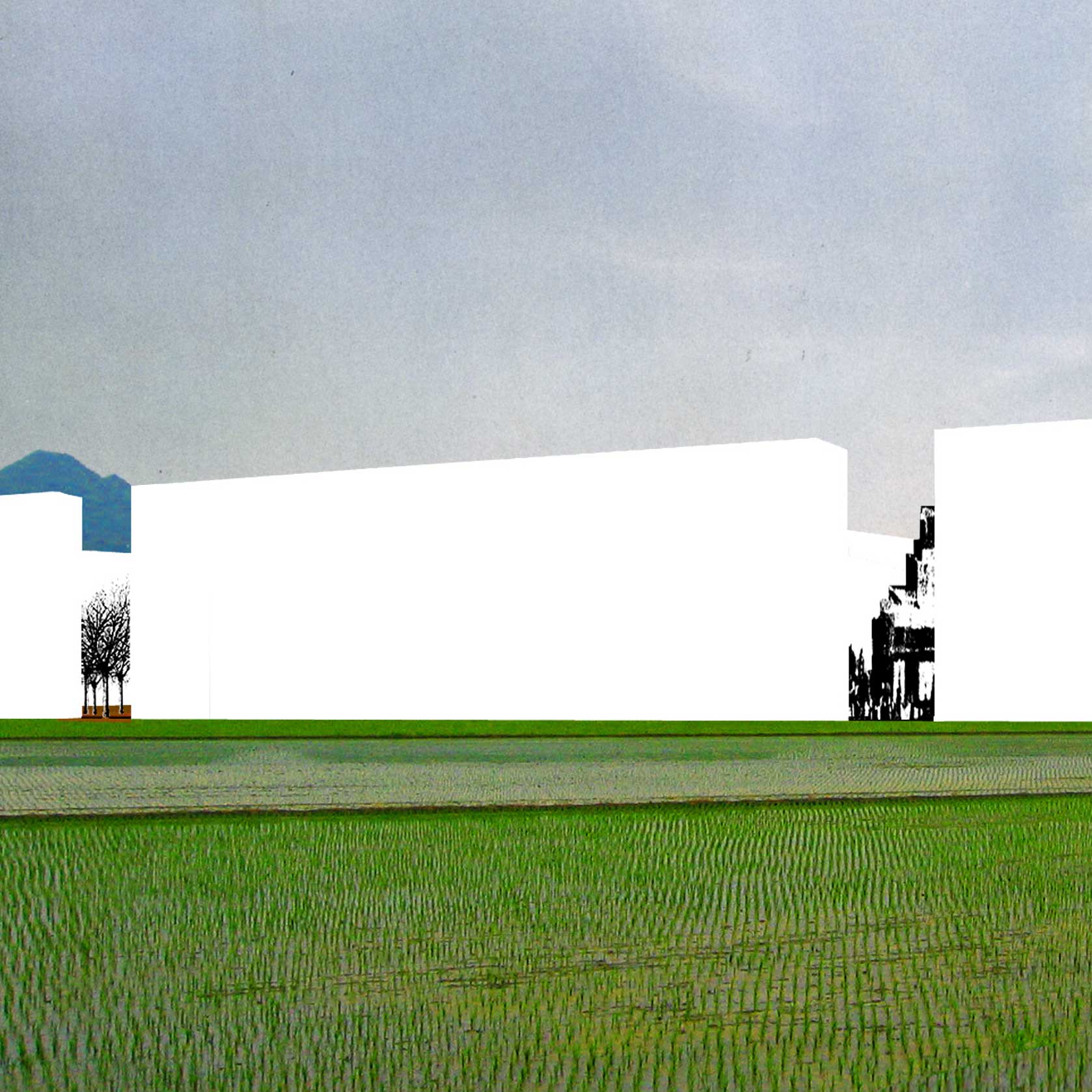

The City Walls drawings for a new city in South Korea by DOGMA and OFFICE KGDVS are an early—if not the earliest—public example of PostDigital collage. Context remains essential to understanding what the City Walls drawings mean. DOGMA’s conceptual and theoretical premises were disruptive and modern in a period of growing technological disbelief. Having understood the new media reality, an image-based reality, PostDigital collage offered the possibility of stating difference. According to marketing theories, the idea of ‘product differentiation’, first coined in 1933, refers to the process by which an item is distinguished from others to make it more attractive to a certain pool of prospective consumers.[2] Differentiation between products can be achieved by means of material contrast, but differences must also be specifically stressed through oral or written descriptions to create an additional sense of value for the user. If DOGMA—or any other office—intended to be different, then, first they had to look different.

The shift from literacy to images—from critique to emotions—as a consequence of the new media environment in architecture was in this case the visual manifestation of an ideological statement: the quest for change through difference; ideological difference conducted through visual contrast.[3] Inscribed within the tendencies of contestation against neoliberal models in the early 2000s described by Michael Meredith as ‘indifference’, DOGMA’s collages relied precisely on difference as political expression.[4] The apparent naivety of their compositions showed up as an ideo-aesthetic technique that having understood the rules of the market located itself in a position of advantage towards potential professional-academic targets.

P.S. The period between 2005 and the 2020s saw the widespread use of PostDigital collage as an architectural representation method, a process that implied positioning collage as a no longer niche contestational device but rather as a generic object. In an article in the Italian journal Piano b published in 2021, DOGMA stated the following: ‘A few years later, we gradually abandoned the use of their work when we realised it had become an unbearable trend, devoid of any meaning.’[5] Quick translation: collage was useful while it was exclusive; if it became a trend, they might prefer to do something else…

Notes

- Sam Jacob, ‘Architecture Enters the Age of Post-Digital Drawing’, Metropolis, March, 2017 <https://metropolismag.com/projects/architecture-enters-age-post-digital-drawing/ > [accessed 4 September 2024], and Mario Carpo, ‘PoMo, Collage and Citation: Notes Towards an Etiology of Chunkiness’. Architectural Design 91, no. 1 (2021), 21.

- See Edward Chamberlin, The Theory of Monopolistic Competition: A Re-Orientation of the Theory of Value (Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1962).

- See Joseph Bedford, ‘Instagram, Indifference, and Postcritique in US Architectural Discourse.’ In The Hybrid Practitioner: Building, Teaching, Researching Architecture, edited by Caroline Voet, Eireen Schreurs, and Helen Thomas, 261–74.

- Michael Meredith, ‘Indifference, Again,’ Log 39 (Winter 2017): 75-79.

- Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, ‘Paint a vulgar picture. On the Relationship Between Images and Projects in Our Work’. Piano b. Arti e Culture Visive 4, no. 2 (2019), 15.

Alejandro Carrasco Hidalgo is an architecture/architectural history researcher at Universidad de Alcalá (UAH, Madrid) and Visiting Academic at the University of Basel, Switzerland.

This text is one of the selected responses to the Open Call: Storytellers, Observed—an inquiry into the origin and circumstances of a single drawing (or series of drawings), observing the ways by which each achieves the specific purpose for which it was made. For further information click here.

– Peter Sealy