Retreat and Commemoration: Heath’s Court, 1878–82 – Part 1

William Butterfield’s architectural practice, spanning the entire Victorian era, is the focus of Nicholas Olsberg’s new book The Master Builder: William Butterfield and his Times to be published by Lund Humphries in October 2024.

Over the next three weeks, Drawing Matter will reproduce a chapter within The Master Builder that focuses on William Butterfield’s Heath’s Court project. Each of the three weekly posts is illustrated with additional drawings of Heath’s Court from the Drawing Matter Collection.

In memoriam

On 1 February 1878 the artist Jane Fortescue Coleridge, wife of William Butterfield’s great friend John Duke Coleridge, ‘drove out’ from their house at Sussex Square in Paddington, then a country suburb of London, to visit the first winter exhibition of the vast new Grosvenor Galleries in Bond Street. While looking at the finest array of Italian Old Master drawings ever assembled in England, Lady Coleridge began to feel unwell and went home nursing an ‘ordinary cold’.[1] This took a turn for the worse the next afternoon, and a few days later she died from an infection of the lungs. She was taken to Heath’s Court, the Coleridge family home at Ottery St Mary, and buried in the great churchyard it stood beside, whose restoration Butterfield and the Coleridges had famously undertaken some thirty years before.

There, two years before, had been laid Butterfield’s friend’s father—and his own once ‘inseparable companion’—Judge Sir John Taylor Coleridge, and Coleridge then took on the south transept, long blocked up, for Butterfield to restore and ‘beautify’ as a memorial chapel to his parents.[2] The great clock would be restored, the walls cleared and decorated, and the windows revealed, with open pews for fifty. Butterfield’s plans were moving forwards at the time Jane died, and they were quickly adapted so that it could be dedicated to her memory, too, with a marble recumbent effigy commissioned from Frederick Thrupp, in which angels guard her head and an otter her feet. Nothing quite like Butterfield’s decoration had yet been seen: vivid, patterned walls in squares of simple geometric tiling inset with panels in tessera mosaic, like the floors of Murano and Torcello, carrying sinuous lines of blossom, leaf, tendril and stamen. All—including the tiny heads and quarries in the window lancets—were rendered in the same palette of gold, maroon and aquamarine, except for two columns of cobalt marble, amid a huge neutral field of alabaster white. A ferny Syrian cross was the only patent Christian symbol in this panoply of abstractions from nature.

‘A life design’d’: the plan

From mid-August to October for many years the Coleridges had stayed at Buckland in the Moor, where John Duke spoke of a landscape, sweeping and sublime, that he often wished for as ‘a lovelier home than Ottery’. But, he writes in 1870, ‘I have made up my mind to stay where my father and grandfather stayed’, and he began to discuss with Jane and Butterfield an expansion of that modest house to serve a long prospect of retirement, to welcome friends to lazy days and to stand—beside the church whose restoration the family had taken in hand—as a landmark to the growing dignity of the ‘house’ of Coleridge.[3] Diffident, solitary, never at home in the city, and uncomfortable with the burden of precedence attendant on her high rank in society, Jane had what was in the town mason’s opinion the remarkable quality of being ‘a lady one could talk to’, and looked forward to living there with nothing but a dog, a vista of skies, her collection of Old Master prints, her sketchbook, the working people of the village around her, and the ‘hilly field’ of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1797 poem ‘The Lime Tree Bower’ for company. She engaged so fully in the first discussions of extension that the new house was, with her sudden loss, accorded another sorrowful memorial duty: to provide, as Coleridge wrote to his friend the theologian John Henry Newman, a residence for her spirit, where he hoped to live out his years in ‘her house’ under ‘her roof’.

Coleridge had met Jane in 1842, and they married in 1846, when Coleridge was called to the bar. Living with his father near Regent’s Park and supporting his family in great part by writing criticism and short essays for weekly journals, he eventually established a lucrative practice in the western circuit. In 1861, he became a Liberal MP for Exeter, then served as attorney general in Gladstone’s first government, was created Baron Coleridge in 1873 when he became Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, and finally rose to become the country’s first Lord Chief Justice in 1880. As John Duke, Lord Coleridge’s income grew, and with his father’s retirement to the country, he and Jane moved to Paddington, eventually acquiring the place in Sussex Square which Butterfield then refined for them, working through the summer of 1868 to fabricate a large library for their vast collection of books and prints, an unaccustomedly spacious study, an entry and principal staircase to carry Jane’s life-size studies after Michelangelo and a famous dining room where fashionable London dined under Butterfield’s infamous wallpaper of ‘seaworms, slugs, and seaweed’.

The house in Ottery had originally been tied to the clerical college at St Mary’s Church as the chanter’s home, and was bought by Colonel James Coleridge on his retirement in 1796 to provide the ‘roof-tree’ under which his progeny would be reared, close to the school which his father had led, and among the meadows where he and his brother the poet had wandered in their youth. It had a famous moment in its history, when Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Fairfax met there in a panelled room in 1645 to sign the Convention that effectively commenced the Civil War.

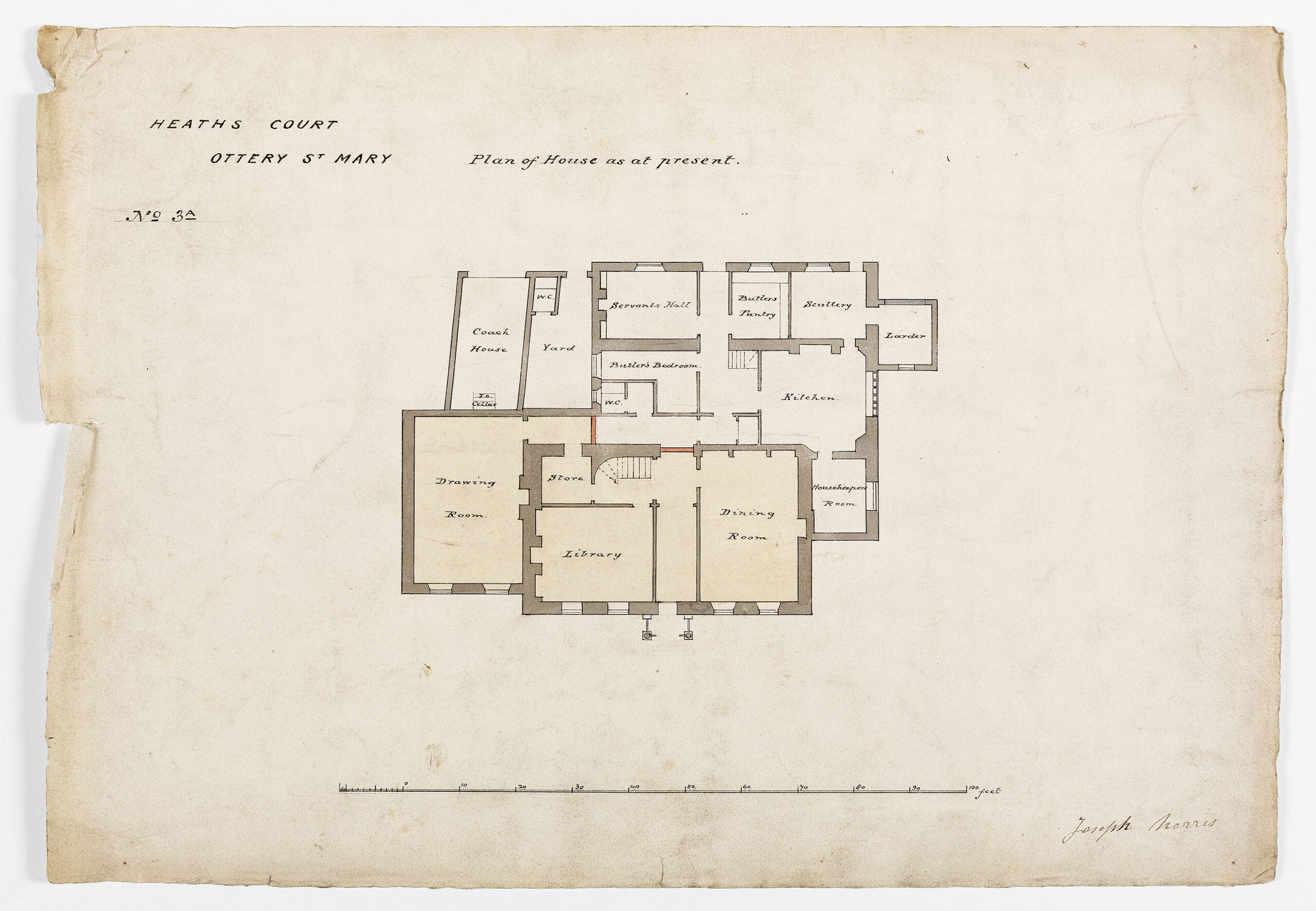

The house seemed to have changed little before 1836, when Sir John Taylor Coleridge inherited it, but in time for his retirement in 1858 he extended service areas to the rear and converted a little garden room to the west, added earlier, into a drawing room. Coleridge was wedded from the start to retaining this original ‘Chanters’ House’, with its echoes of great events in the Civil War, of a father with whom he had been as confidential and intimate as a friend, and of a wife whose loss could be partly recovered by suffusing it with her memory. There would be no great halls, grand avenues, splendid carriageways, ascending entries or fine ballrooms.

He was looking for a home which could furnish his retirement with ‘lettered ease’, welcome his many friends to an atmosphere of ‘stillness, quiet, and delicious idleness’, fit the figure of a man who stood 6 foot 3, and accommodate one of the largest private libraries in England, all the while leaving its principal rooms from the seventeenth century intact. But Coleridge asked that it also represent the particular ‘aesthetics’ of its history, proprietors, site and setting. This was the term his great-uncle Samuel Taylor Coleridge had been first to use in discussing the fabrication of beauty, demanding that art seek ‘unity in variety’ and express an innate truth to itself, an intuitive aesthetic that we might call ‘character’. The sense of how this aesthetic richness might emerge from the comforts of ‘a life design’d’ was strikingly imagined in Tennyson’s ‘The Palace of Art’, a popular poetic fantasy of the ideal ‘English home’ whose adornment would recount ‘cycles of the human tale’ and whose Socratic ‘sounding corridors’ would echo with the discourse of the learned. [4]

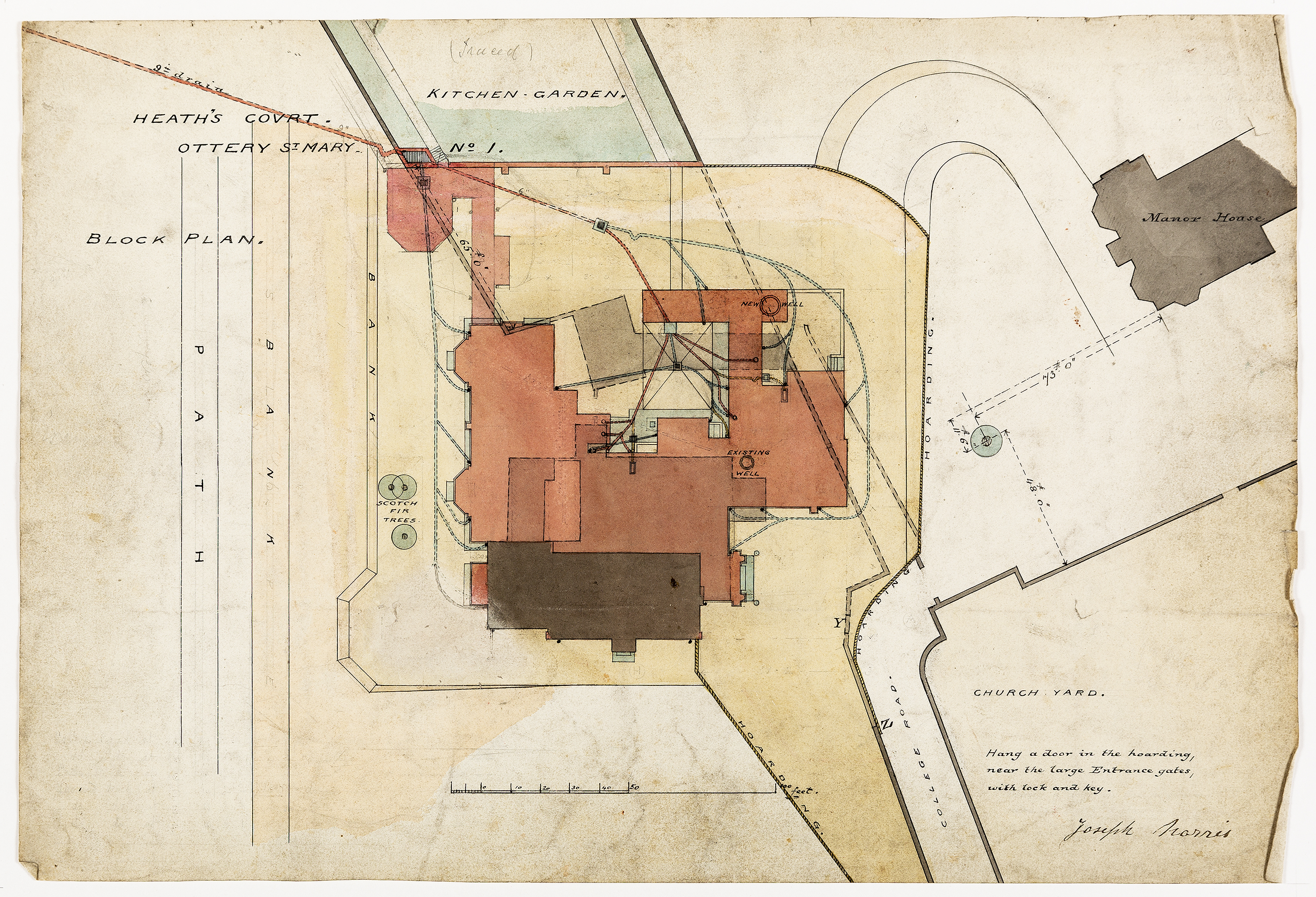

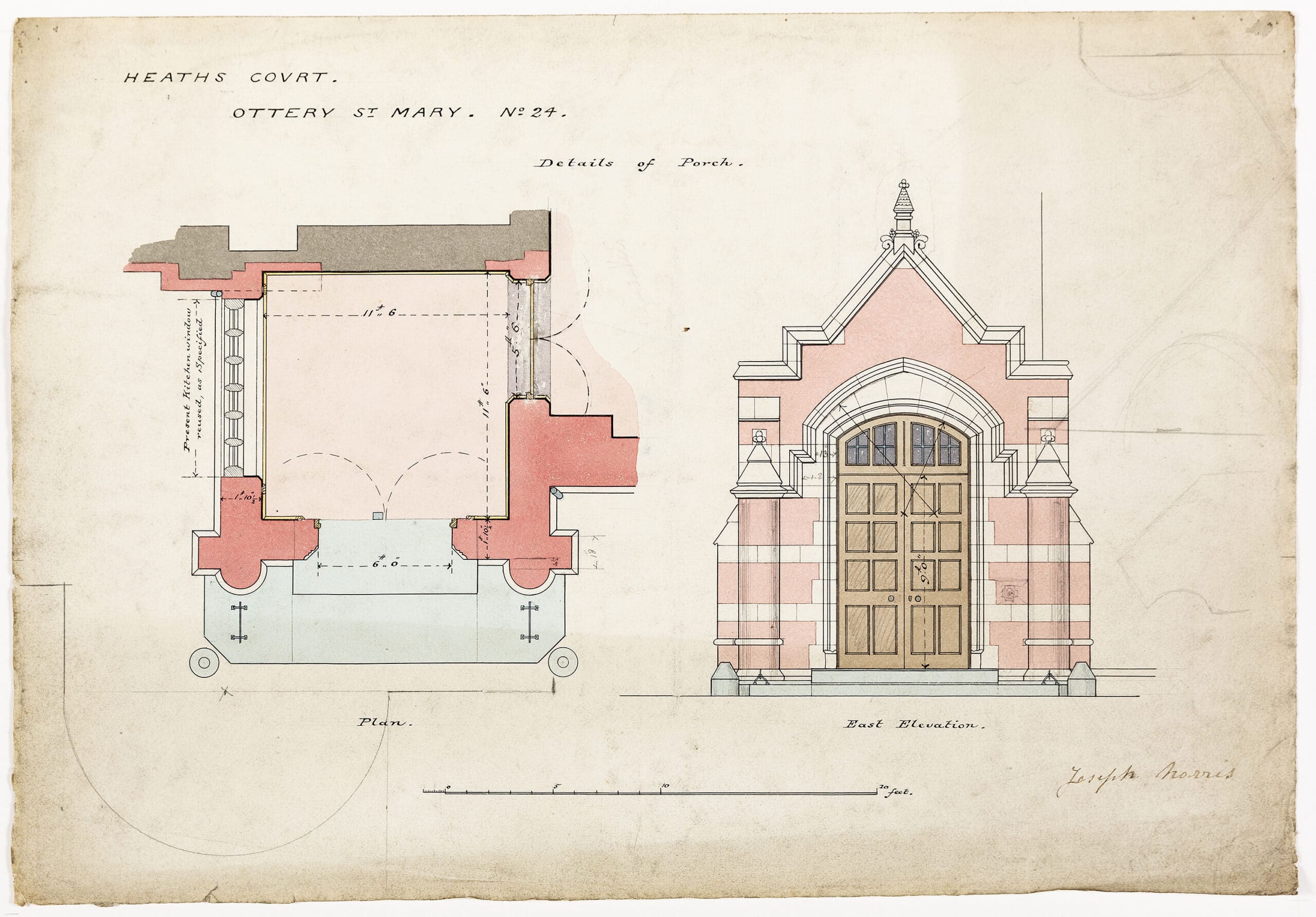

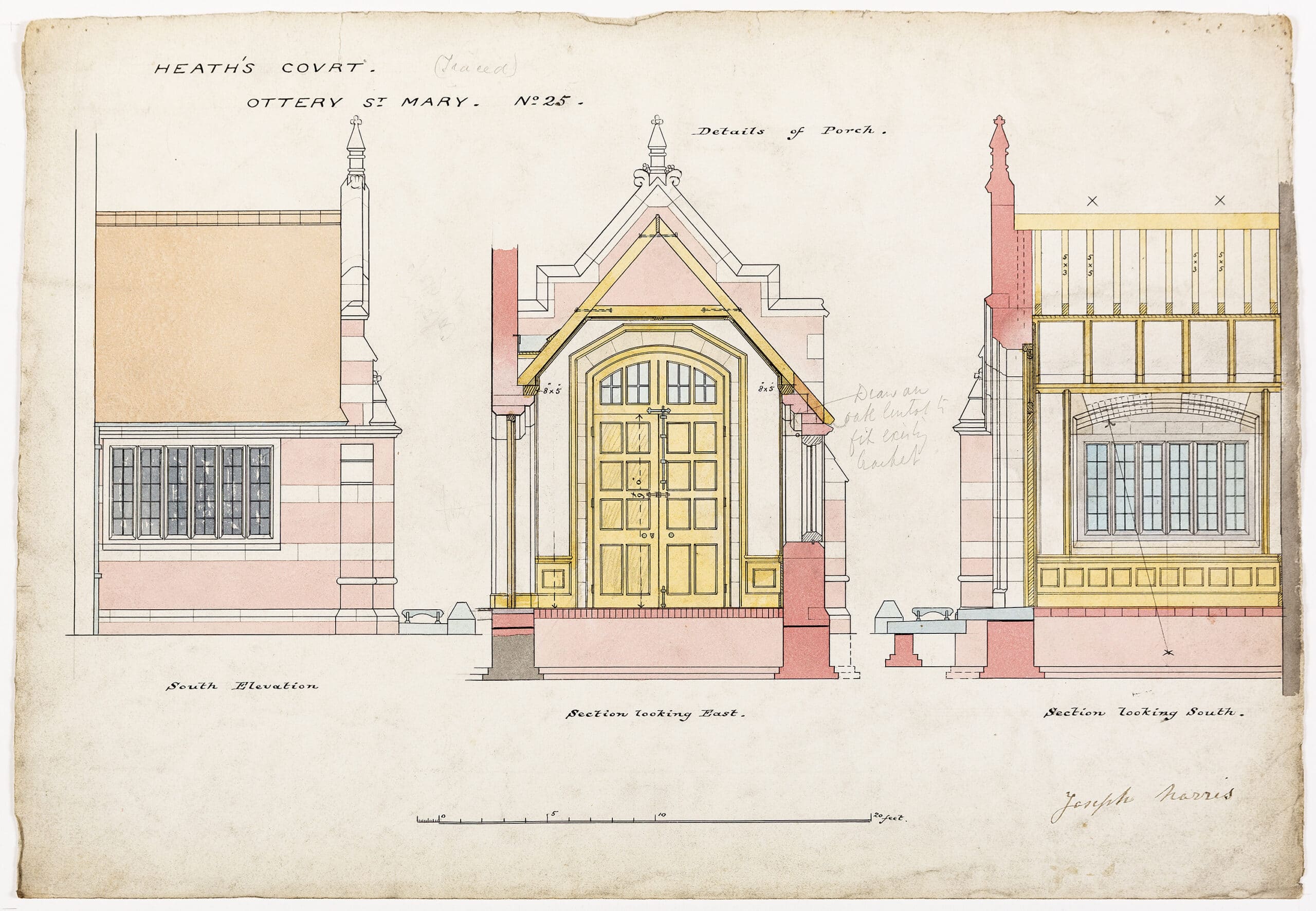

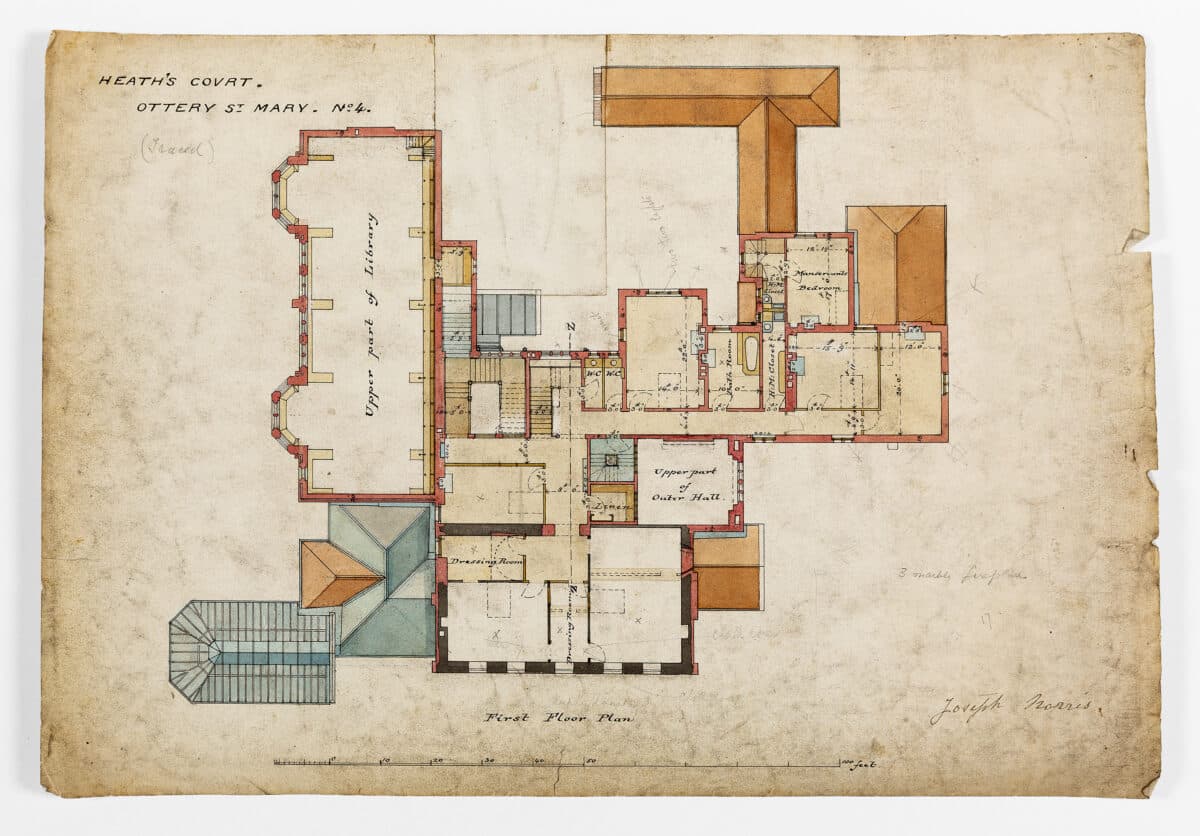

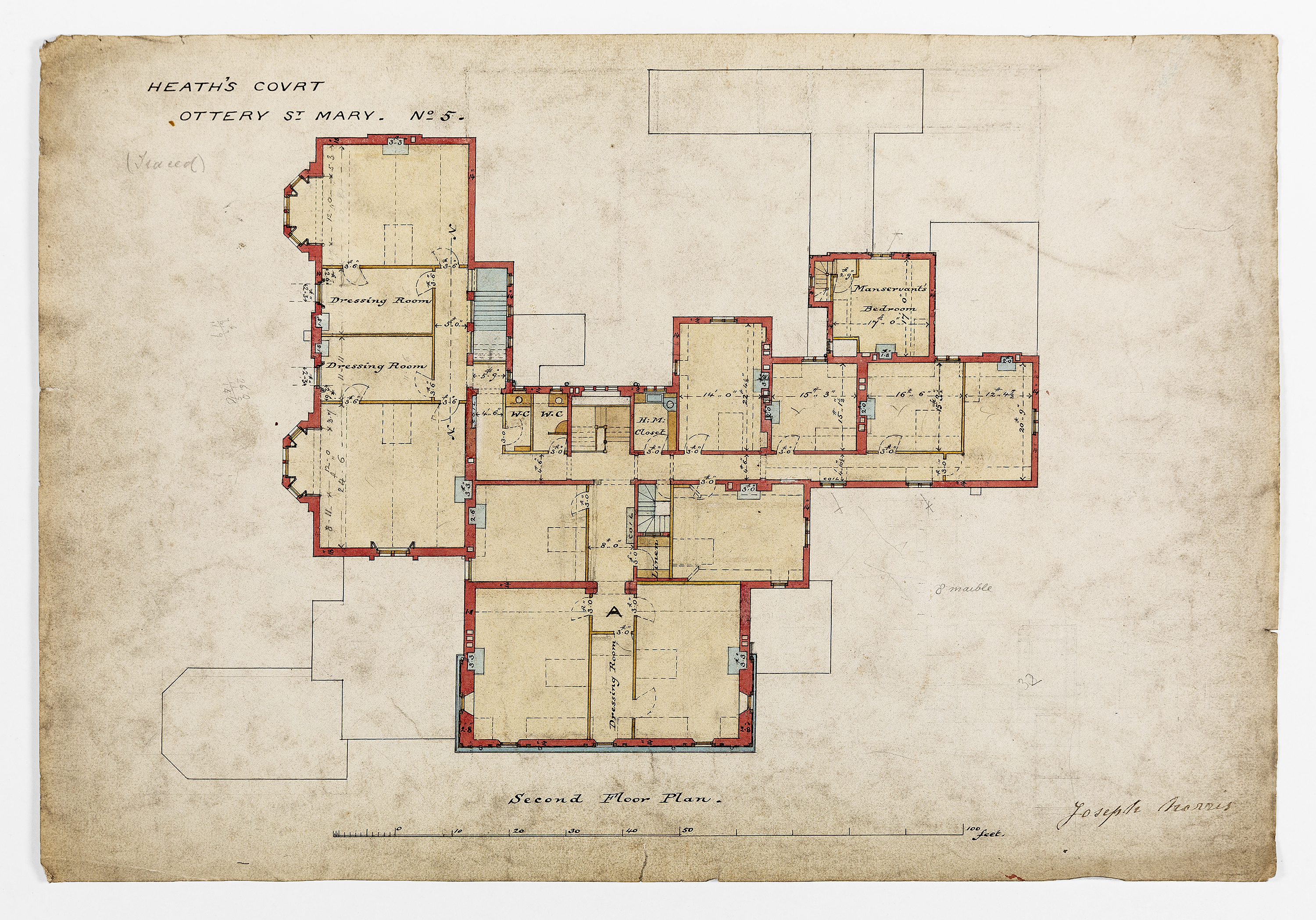

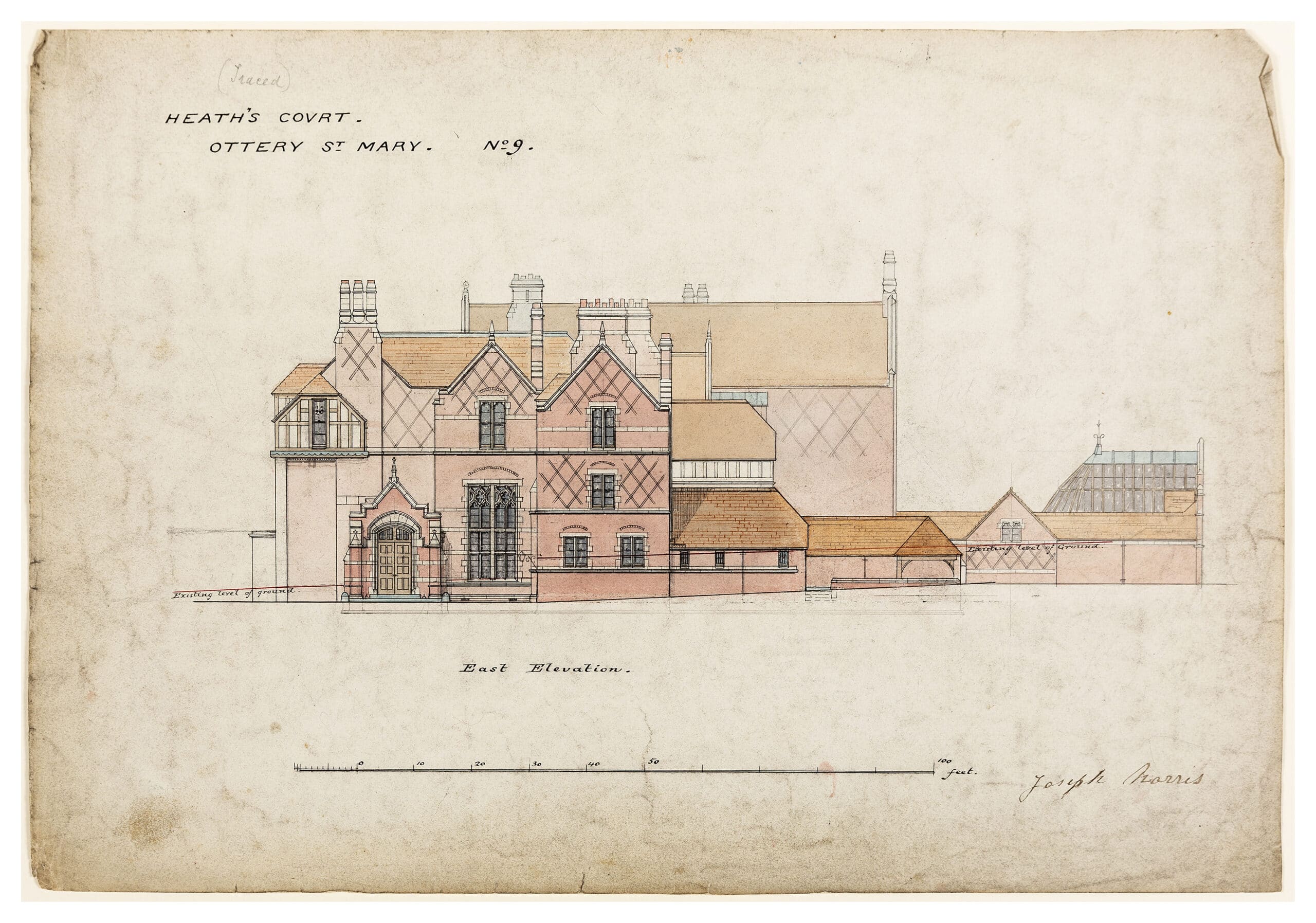

Client and architect were so close that we must imagine them virtually working together. Contract drawings were mostly completed by late summer of 1880. Butterfield and Coleridge were looking at wood samples in the beginning of October, and later that month Joseph Norris costed the project and supplied a timetable, based on commencing groundwork in January, with occupancy in August 1882. In the New Year holiday of 1881, Coleridge moved into his sister’s house at the Manor behind the church; books, art and furniture went into sealed storage in the front rooms of the old house; and the extensive outbuildings, kitchen, offices and other rooms erected in 1849 were demolished.

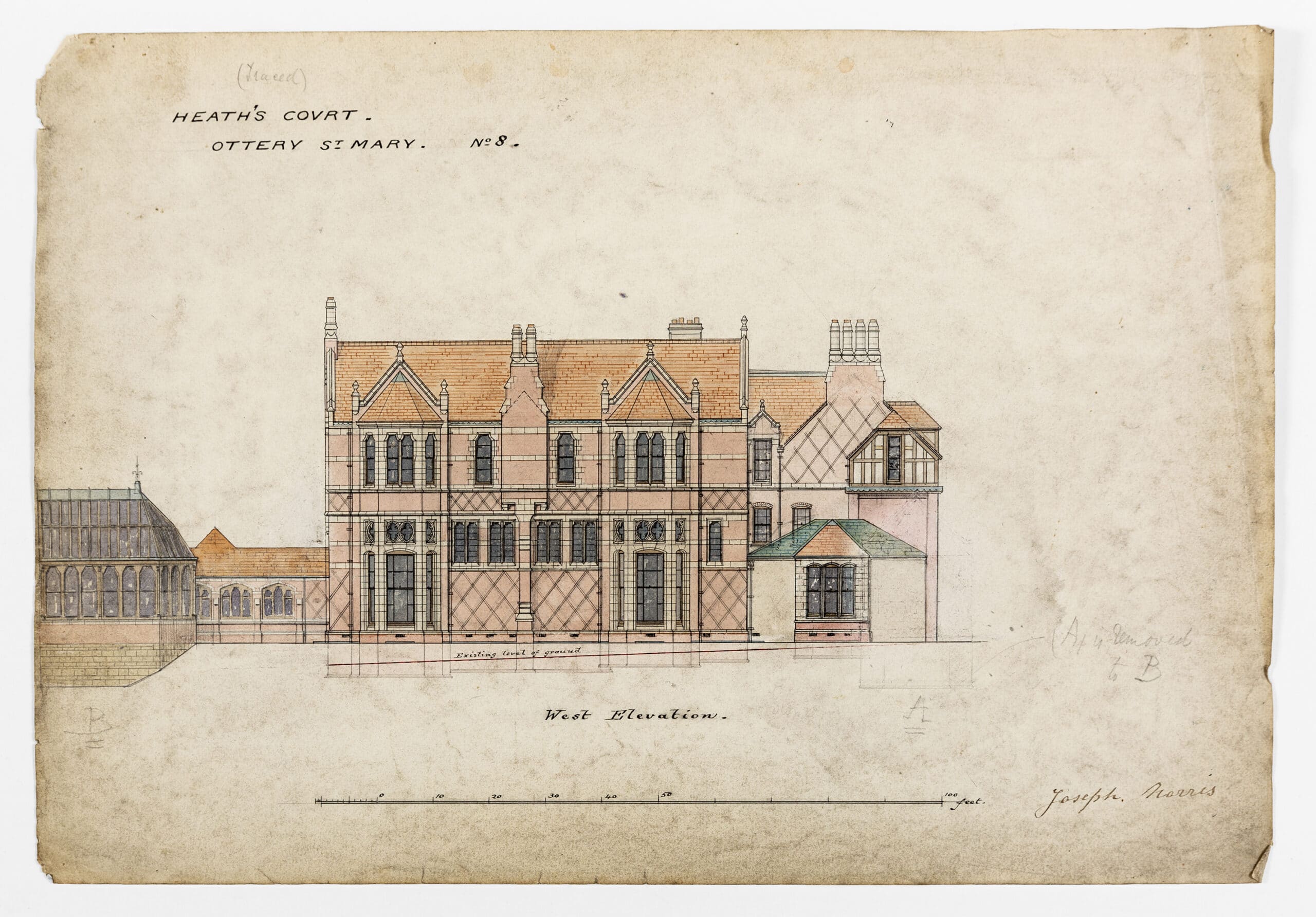

The task of levelling the ground and managing its landscape was enormous: drawings show a 14-foot drop from east to west under the built footprint and 15 feet falling from north to south. A vast system of terraced landscape to the west of the house was needed to accommodate excavation and fill, laid down in Butterfield’s familiar pattern of precise parallel lines, with trees scrupulously protected. Work slowed in the first summer campaign of 1881, as the conservatory was entirely rethought, and again in the following year when Coleridge had a long period of painful illness. But reports in November 1882 say the house was then almost completed, and a grand ball for 150 was held in the library to welcome the new year of 1883. Gates and walls continued to be built until August that year, when Butterfield submitted a final bill. The total cost was just under £17,000.

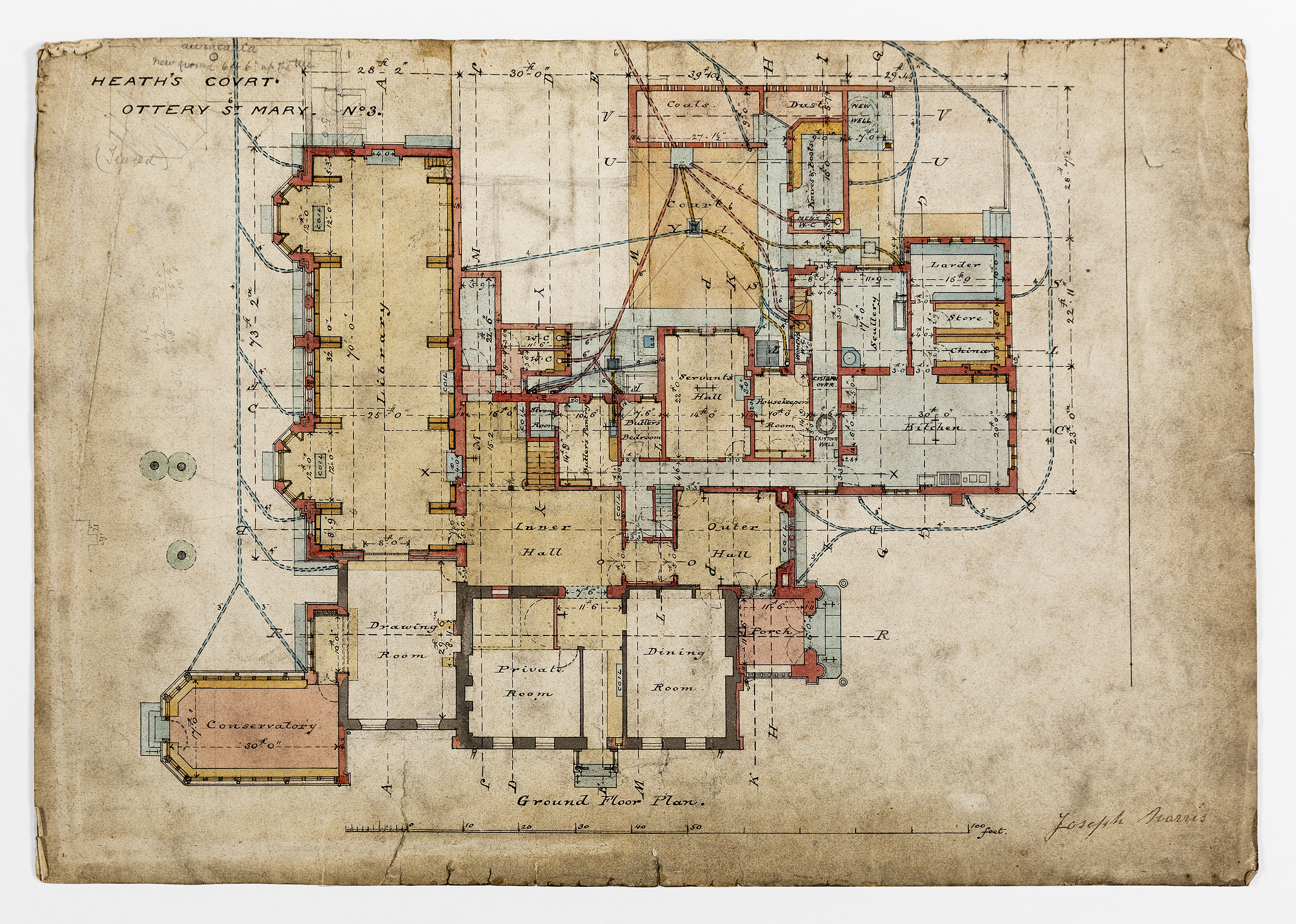

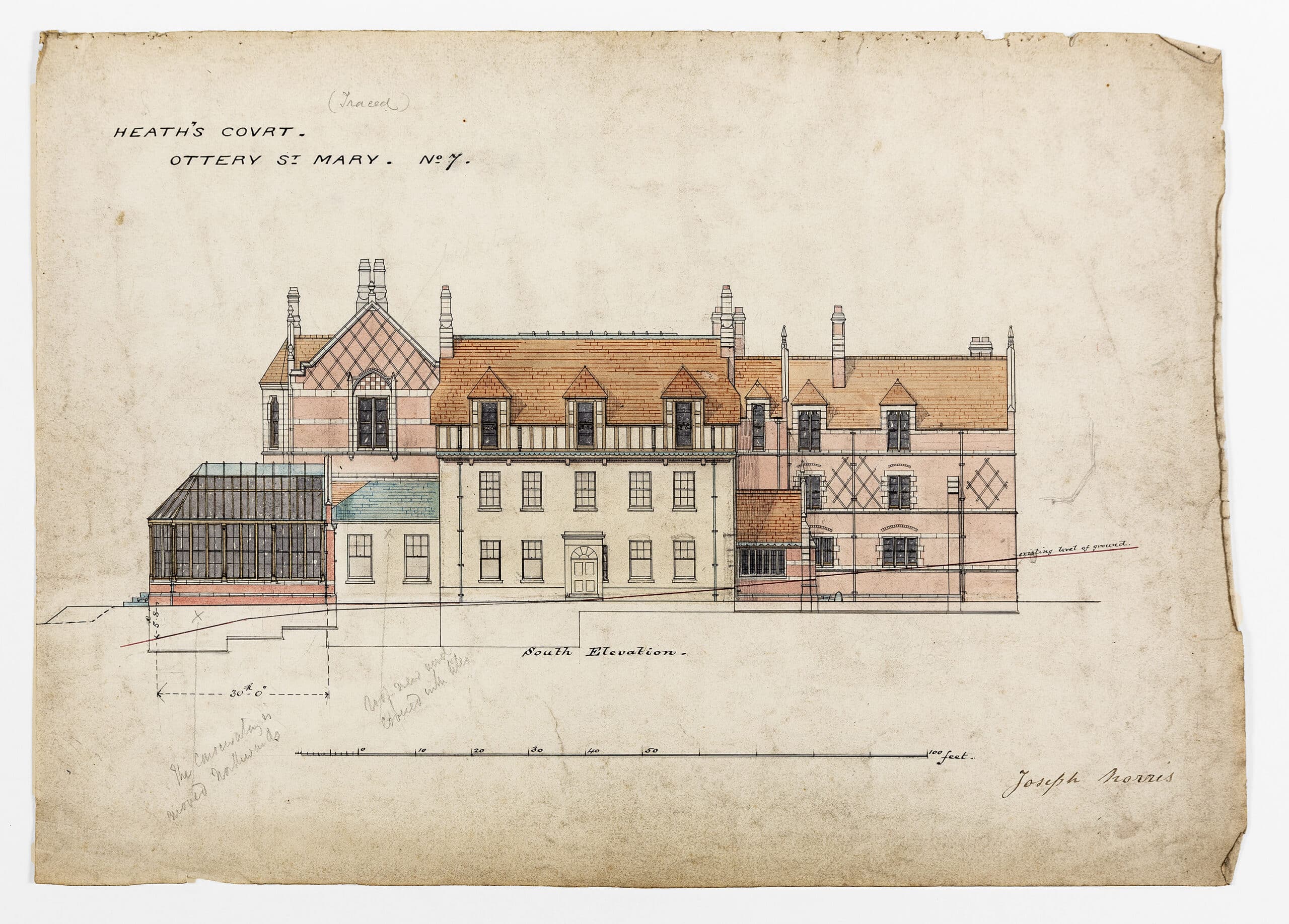

The great entry porch at the centre with the massive east window of the hall beside it indicates very clearly where the central two-storey circulation path runs behind it. A new north block of kitchen, services and staff bedrooms lies on the right, continuing to the west for some distance behind the old house to enclose the passages through the inner core; an arched entry separates it from a long low L of sheds and other ‘offices’ forming the north-east corner of a service court. The small dining, drawing and private rooms of the old house to the left face south with a passage and door to a sitting garden; the original visitor and family chambers above are left intact; but an entirely new bedroom floor at quite a different scale rides over it, marked out from the generations of building beneath by an assertive end gable and continuous timber framing. There were ten bedrooms in addition to the manservants’ suite on the second floor and another six on the first.

Nothing in either approach to the house, from the north courtyard or west gardens, reveals the other element of this scrupulously divided building, in which the separate parts are folded into a single cube. This is a tall symmetrical pavilion on two floors, running south to north on a newly graded platform above the meadows to the west, with a range of high wide windows, the most important of them set around two projecting bays. Within is a galleried library the length and width of a nave—70 feet long, 22 feet high and 25–30 feet wide—with two huge principal bedrooms above, lying under 20-foot coved ceilings. Here, pattern, scale and proportion, echoed precisely in the courtyard entrance façade, have a life and character entirely unrelated to the original house, luxuriating in the burnt-orange clay brick of the district.

The general plan ensured that servers and served, the workings of the household and its pleasures, were scrupulously kept apart, yet the overlapping of the volumes makes for extraordinary efficiency. There is only one moment on each floor where the two lives intersect, seen in the 10-foot-square shaft that breaks the inner from the outer hall, where the service stairs and lift appear, and where what Butterfield calls the kitchen corridor is carried out to the east. It is a system that allows food to flow into living and entertaining with a minimum of visible traffic; but it also permits Butterfield to provide staff with the extraordinary comfort of a 30-by-40-foot kitchen, scullery and pantry, at the cool north-east boundary of the home. The first plan was for a conservatory on the south-west corner, entered from the simple drawing room that had been added by Coleridge’s father in the 1840s; but by August 1881 the conservatory was expanded, with an aviary and promenade, and moved north to an outlying site, 54 feet long, that required excavating a much larger level platform for the house.

Most of the drawings where the amendments were minor were simply left in the previous configuration; but east and west elevations were revised to convey the profile of the new long cloister with its aviary, and the winter garden turned to face back as an apostrophe at its furthest end. Approaches and perimeter walls were not fully defined until February 1882, with steps, gates and walls to the churchyard, a diapered high brick fence between carriageway and gardens, and a resplendent brick gate at the entrance from the college road.

Notes

- The obituary by Dean Richard Church of Jane Fortescue Coleridge is in The Guardian, 13 February 1878, and notices of the funeral proceedings in the Western Times, 15 February 1878.

- The chapel is described at its opening in the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 16 September 1878, The Guardian, 18 September 1878, and Building News, 20 September 1878.

- The project history of Heath’s Court is drawn principally from biographical sources and recollections, especially volume 2 of Ernest Hartley Coleridge, Life and Correspondence of John Duke Lord Coleridge Lord Chief Justice of England, William Heinemann, London, 1904; Lord [Bernard] Coleridge, The Story of A Devonshire House, T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1905; and from newspaper reports, notably Western Times, 31 January 1881, as work commenced, and Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 30 November 1882, as it reached completion. Butterfield’s letters to Coleridge on the project—in the Coleridge Family Papers, British Library—date mostly from the initiation of tender in autumn 1880 to his final accounts in spring 1883, including letters relating to the work at Alfington church in 1882. Of the many memoirs, exchanges of letters and recollections describing the house and its proprietor, those drawn upon the most extensively are William Pinckney Fishback, Recollections of Lord Coleridge, Bowen-Merrill, Indianapolis, 1895, and Charlton Yarnall (ed.), Forty Years of Friendship as Recorded in the Correspondence of John Duke, Lord Coleridge, and Ellis Yarnall During the Years 1856 to 1895, Macmillan & Co., London, 1911.

- Alfred Tennyson, ‘The Palace of Art’, 1832, revised 1842.

Nicholas Olsberg was Director of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal and founding Head of Special Collections at the Getty Research Institute. He holds an honours degree in Modern History from Oxford University and a doctorate in Nineteenth Century history from the University of South Carolina. He has written books on the work of Herzog DeMeuron, Carlo Scarpa, John Lautner, Cliff May and Arthur Erickson, has been a columnist for the Architectural Review and Building Design and has contributed to the curatorial programme of Drawing Matter Collections since its inception.

In the second episode of series two of British Art Matters, Dr Christina Faraday speaks to Nicholas Olsberg about his insightful and comprehensive survey of Victorian architect William Butterfield.