OMA: Rotterdam—Child’s Crusade

This is the third post, in a series of six, titled OMA CONVERSATIONS. The series is the result of a collaboration between Drawing Matter and architect Richard Hall who, over the past two years, has conducted twenty-three in-depth conversations with key collaborators working with OMA during its formative years. Drawing Matter has long had an interest in the work of OMA in this period, in particular the role of Rem Koolhaas in establishing the model of a horizontal organizational structure and the purpose, and techniques, of drawing in its distinctive repertoire.

ROTTERDAM—CHILD’S CRUSADE draws from conversations with Kees Christiaanse, Paul de Vroom, Herman de Kovel, Ruurd Roorda and Willem Jan Neutelings—collaborators aiding in the formation of OMA Rotterdam. All are ex-students of Koolhaas’ studio at TU Delft, enlisted to fight in the Child’s Crusade.

Upcoming posts in the series include focused conversations with individuals working on the early big competition projects as well as external collaborators (‘satellites’)—who worked across the different OMA locations. Find more about the project, including a list of the upcoming posts, here.

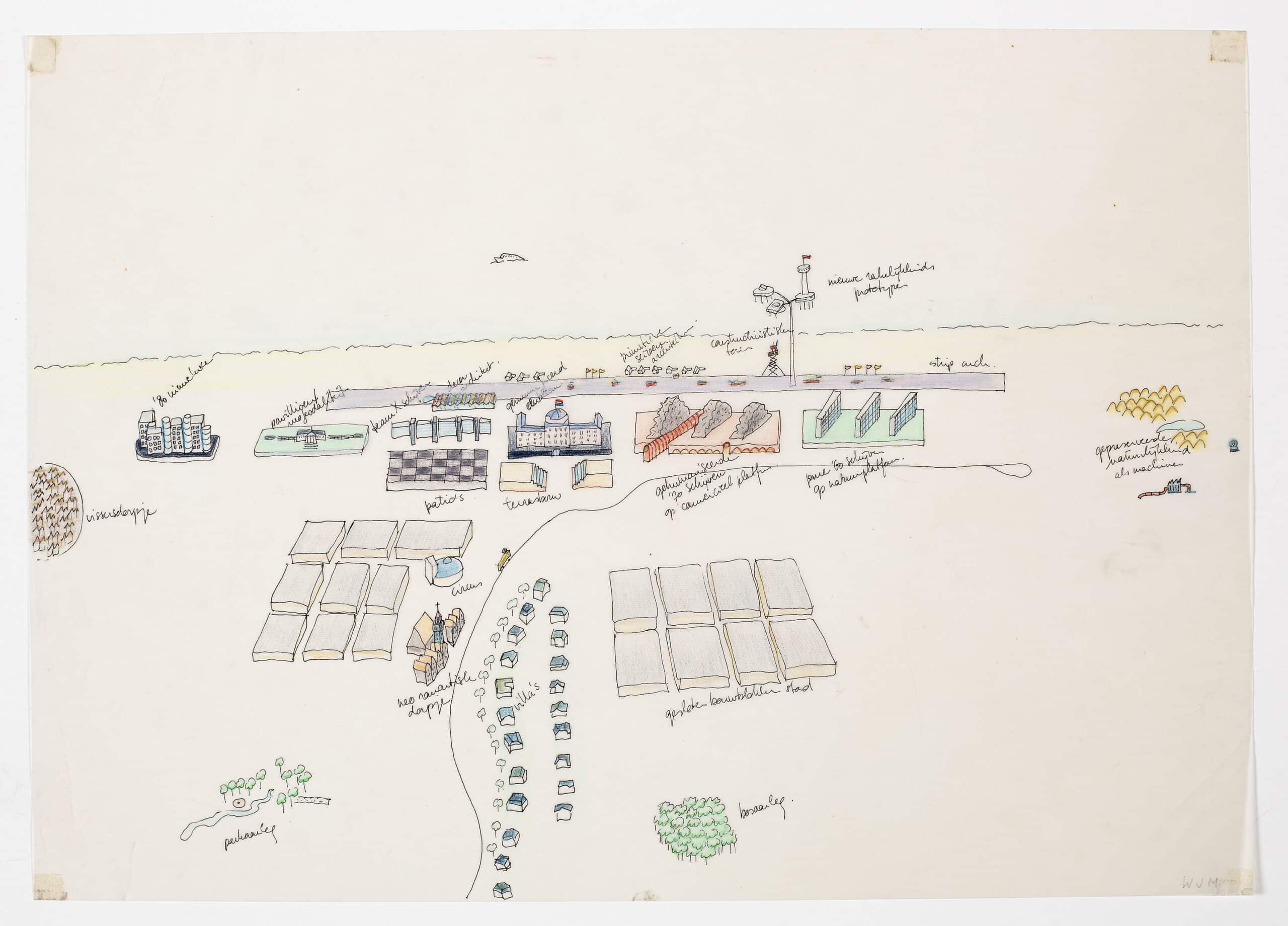

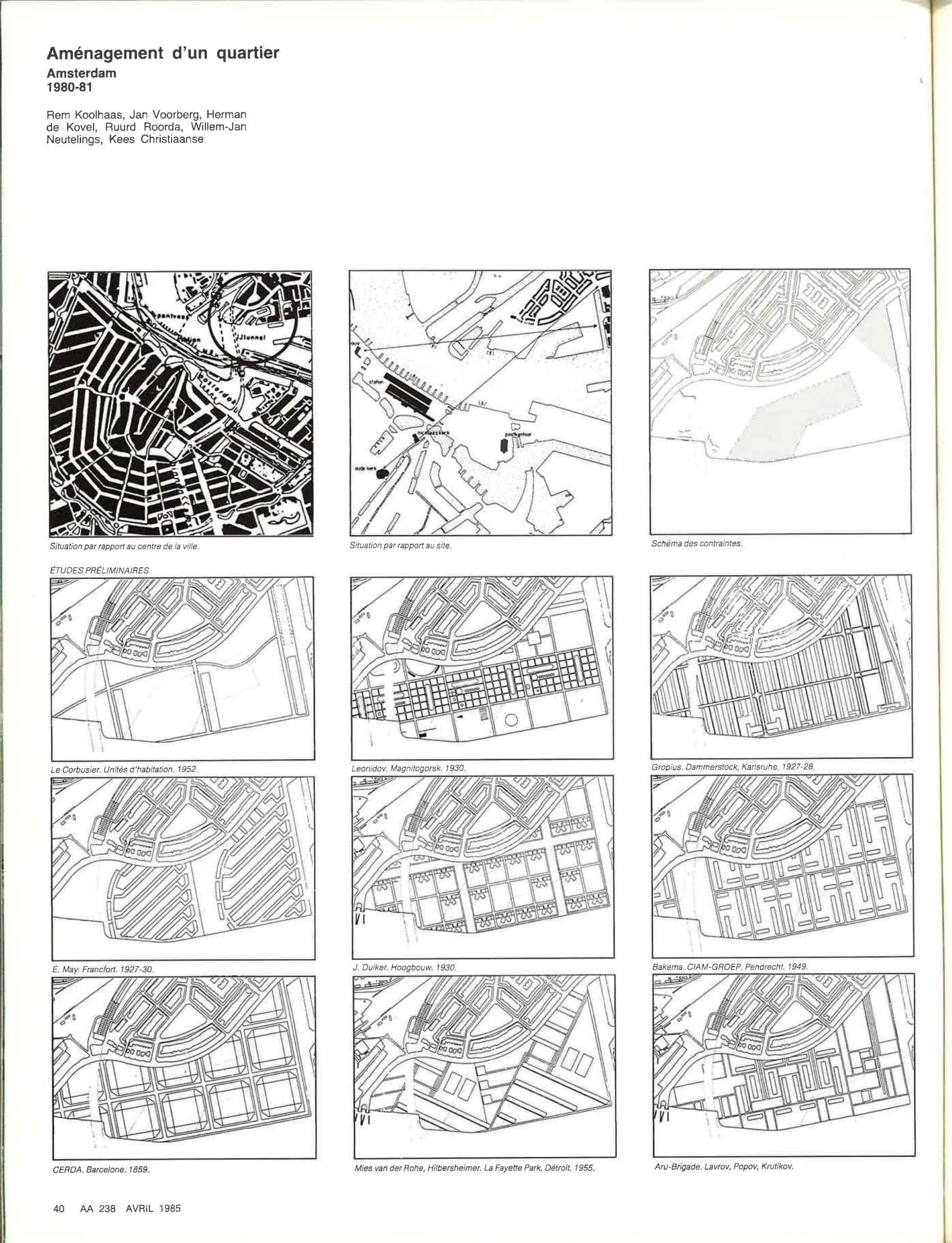

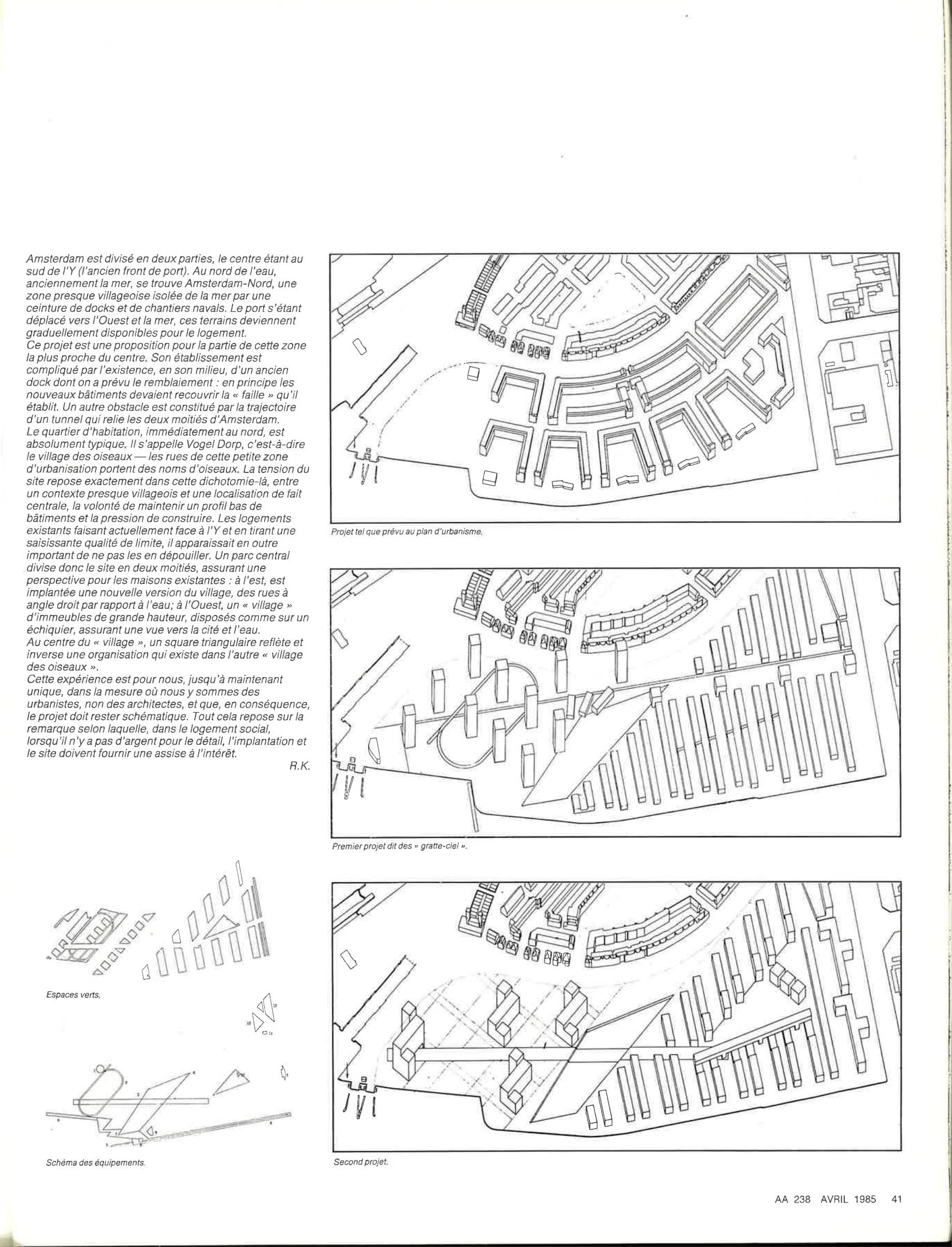

Following the publication of Delirious New York and the unsuccessful but highly acclaimed competition entry for the Dutch Parliament Extension in The Hague (both in 1978), OMA gained two public commissions in the Netherlands. The first was a high rise building study for a negligible site on the Boompjes in Rotterdam, the second as a wildcard facilitator of the master planning process for IJ-Plein in the former northern harbour of Amsterdam.

Suddenly, what had effectively been an intellectual enterprise was subject to a quantum leap into professional practice. This process was aided by Koolhaas’ encounter with Jan Voorberg—an architect practising in The Hague with an established knowledge of the Dutch regulatory system, who would become an instant partner in the fledgling Rotterdam office—and the initiative of a crack team of students from Koolhaas’ studio at TU Delft.

OMA’s aggressive campaign to build during this phase resulted in a mix of critical acclaim at the conceptual level, and battle scars in the realisation process. Both of these traits are apparent in the delivery of the office’s ‘first’ concrete victory: the Nederlands Dans Theater in The Hague (completed 1987).

‘Actually, the office was very much pre-occupied with trying to figure out how to transform from a paper architecture group into a practising architecture firm, without losing the former’s qualities. Rem called this ‘The Children’s Crusade’, meaning inexperience people trying to quickly conquer a successful position in the profession.’

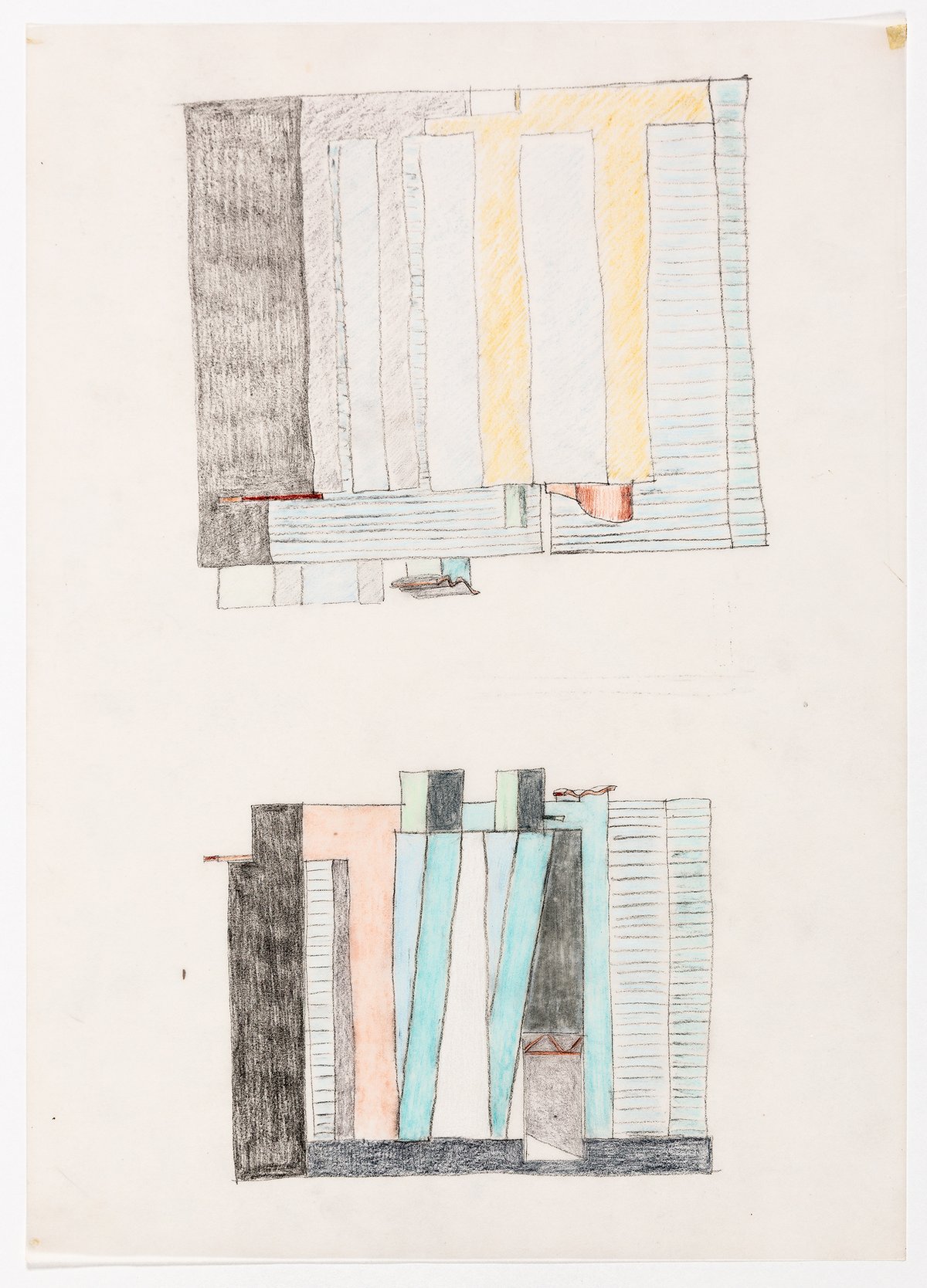

‘Being in a children’s-crusade, we had to become professional overnight. The culture of the office led, in the most interesting cases, to a complementarity merging of conceptual and technical drawing. There were draftsmen entering the office who made technical drawings, which fascinated us, because we thought that that was ‘the real thing’. This influenced the way conceptual and spatial visualizations were produced. I guess the visualisations became, on the one hand, more focused in their narrative and explanatory role, on the other hand, they had to be produced faster, because of the time-schedules of real projects and the increasing workload, which also led to new techniques. The meticulous character of the original OMA drawings and paintings, which were very time-consuming, did not work in this new condition. Also, I guess technical drawings became more narrative and conceptual under our influence.’

‘In the essential projects of OMA, Rem’s conceptual and design-guiding role was indispensable and dominant. He was very demanding and not interested in compromises. He also was willing to take a lot of risk. He was conceptually superior to all of us and very inspiring, but also not easy to work with. However, as I noted before, the great thing about Rem in comparison to many of his renowned colleagues is that he was not interested in whether a good idea was his or someone else’s. He always had a nose for—and opted for—the best idea, independent of its author. As he could do this, his leadership was accepted by the team, and it reinforced the willingness of the designers to work as a team. This is a kind of spiritual and intellectual generosity that not many people dispose of. And in the end, this character trait made up the unique quality of OMA, which produced so many successful designers.’

‘OMA put architectural design back in the middle of the profession. The work that was produced, the ideas, the way of working had a worldwide impact on architecture and design culture. If you look how many offices all over the world have been established by people who worked in OMA, who also translated their experiences into their own work in a way that was somehow still relative to what was done at OMA. It’s just amazing. It’s an enormous legacy, a major transformation and re-acknowledgement of the role of design, visualisation and communication in architecture and urban design.’

— Kees Christiaanse Transcript click here.

‘I came back in the autumn and then he started the office. He had no office space, so we started in Jan Voorberg’s apartment—that was his partner at the time—in The Hague. Then he rented an office in Rotterdam where it was just me and Jan Voorberg. Rem joined us three days a week in Rotterdam and the other days he was in London. After two months we needed extra people. Rem knew about Paul (de Vroom) because of what he was studying for his final project, and I asked Kees Christiaanse to join as a student worker. We knew each other from TU Delft. As you know, Rem makes no distinction between students and qualified architects. It’s all the same for him. So, Kees started before he finished his studies. It ended up taking him seven or eight years before he was able to complete his diploma.’ (Herman)

‘This (blue box) is essential for my connection to Rem Koolhaas. When I met him, I was working on an urban research project together with my fellow student—and later office partner—Dolf Dobbelaar. We were investigating iconic urban planning, and these plans were collected into a suitcase because I was homeless. I needed a suitcase every night to work when I stayed with friends.’

‘…I started to make objective projections of grids—I was obsessed with grid systems—on to my final diploma project site, without designing anything. This very much intrigued Rem, so he asked me to use the same kind of method for IJ-Plein. These are some of the systems I projected, you can see: left above, Ildefons Cerdà’s Ensanche in Barcelona; below, Tony Garnier’s Cité Industrielle; right above, Ernst May’s Siedlung Westhausen; and underneath is the planning Le Corbusier did based on the Unité d’Habitation. I projected something like 22 of these projects.

Together with Rem and Jan Voorberg, we decided which ones we would choose for the IJ-Plein. Of course, not everything is usable on a specific location, so we agreed which were suitable and we projected them onto the site. For IJ-Plein we also went to Amsterdam to use this technique with the residents. In The Netherlands, people from the neighbourhood had a big say in the development process. That was really the democratic way of Holland in the ‘80s. It was all about talking to each other. We went there in the evening and introduced these studies.’

— Herman de Kovel and Paul de Vroom Transcript click here.

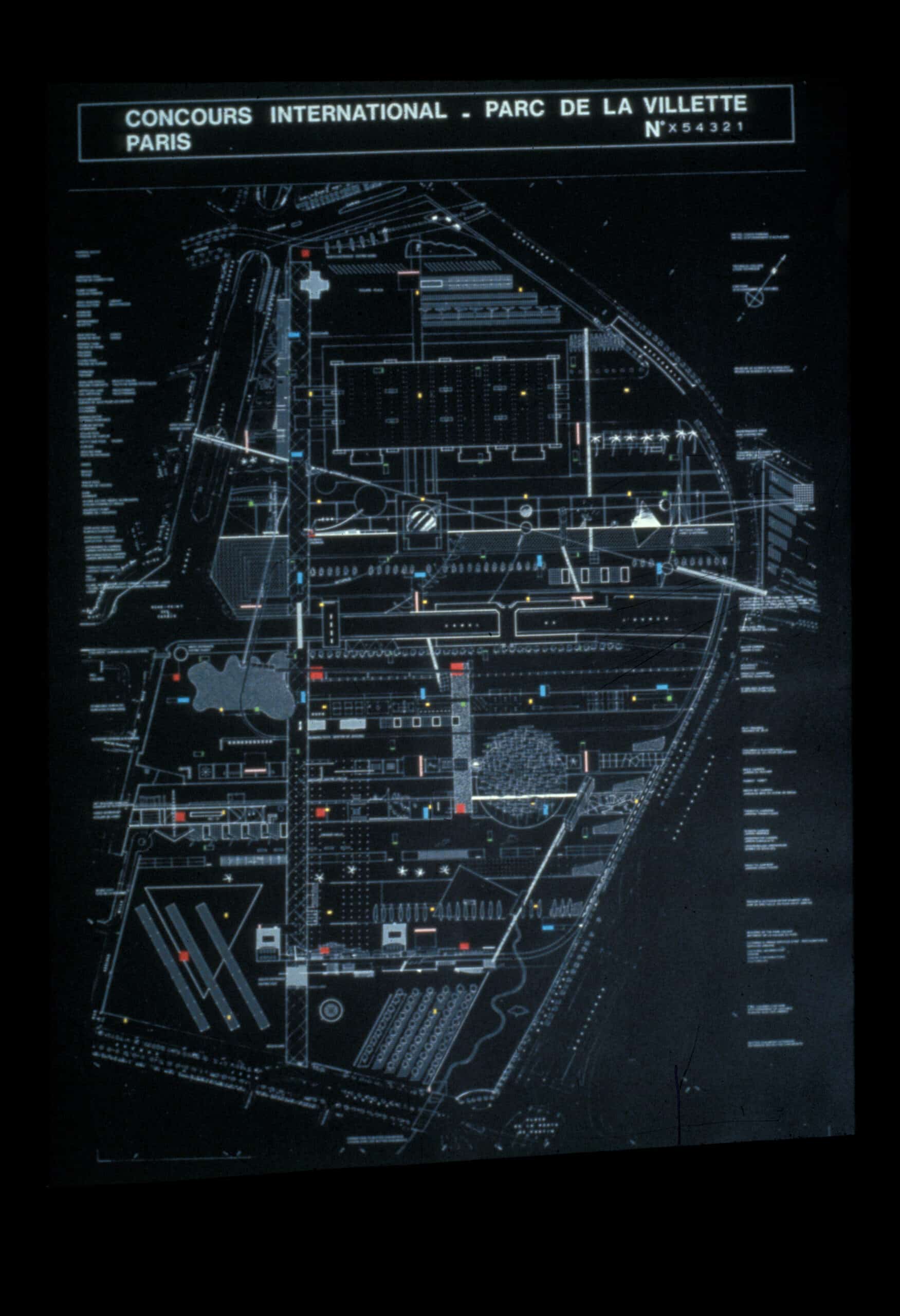

‘I drew it and it was made into a silkscreen. We put Letraset colour stickers on to highlight the confetti; the point grid. As I remember, one evening we went for dinner at Rem’s apartment—that was the only time I went there, together with Kees—and then Rem explained the way he wanted it. How he wanted me to draw the trees, in elevation. It was based on very ancient drawings of palaces with gardens. This is really a project that we all worked on. I think the point grid thing was done by Elia: the overlapping of grids based on the distance that was mentioned in the brief for certain services.’

‘Putting things together and putting people together; grasping their best ideas and making something new out of it. That’s important. But, if you ask me, I think Rem taught me to think about things and write them down—to remain rationalised—and also try to get to your own weaknesses. For me, he has been very influential.’

— Ruurd Roorda Transcript click here.

‘This drawing is one that I made, I guess. Sometimes there’s a name on it, it happens not so much. This is a drawing of the version in The Hague, where we merged the concert hall and the dance theatre in one building. But of course, it never happened because there were two clients and two architects. This is a very simple drawing with a felt pen—a fine liner—on transparent paper. We used fine liner a lot because it was an easier way to ink. Before you would use pencils, but the pencils of course didn’t give gives a lot of contrast, so then you would ‘ink’ the drawing with a Rotring pen—the old pens to line drawings—but you can’t do a real hand drawing with them: it’s too scratchy. So, the other option is to use fine line pen. The felt pen was an invention from the late fifties and the sixties, which then became more common.’

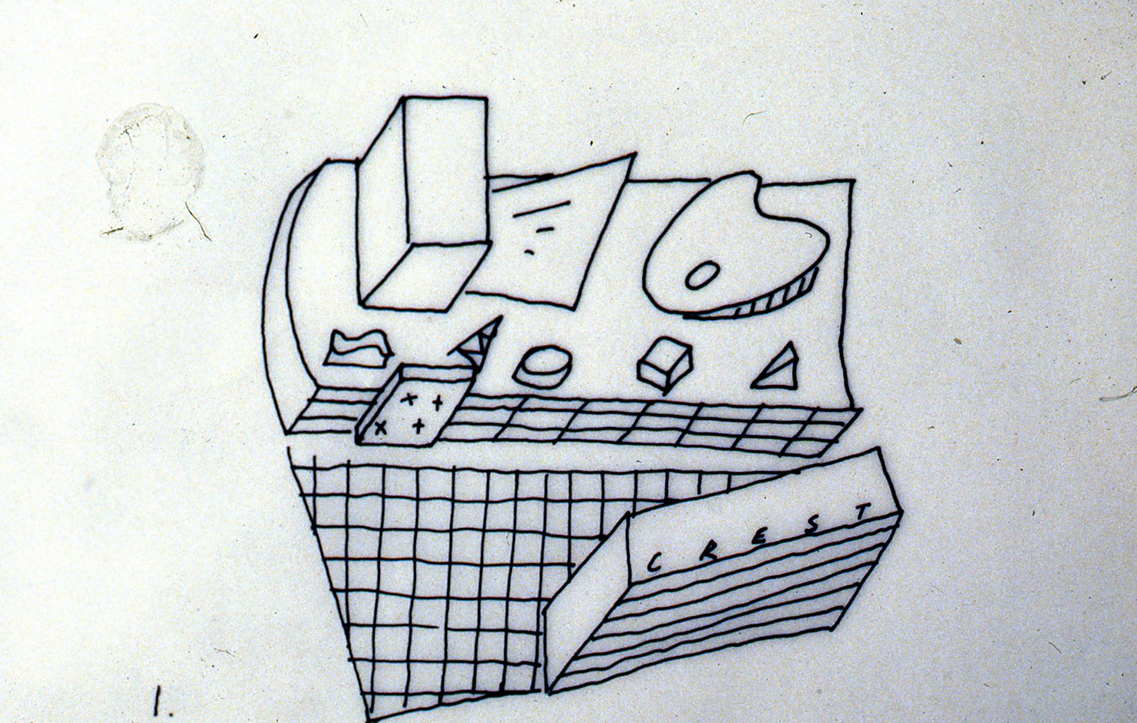

‘I was raised in Belgium and Belgium is the home place of cartoons, and the famous Tintin. So, I always made these kinds of drawings already when I was younger. What is very interesting in cartoons is that, with very few lines you immediately know that you’re in New York or in China or in Yugoslavia or whatever. They are able to capture a situation or context in very few lines and—not only the context itself—but also the spatial concept, the emotion or atmosphere of the scene. That always amazed me.’

‘Strangely enough, in the seventies when I was taught architecture, we were taught to draw in a very complicated way. The architectural drawings in the seventies were extremely complicated. You needed to do a lot of lines. If you had a lot of lines, it was considered very interesting…and the lines had to cross! I really didn’t understand why drawings had to be so complicated. So, I always liked cartoons as a drawing method to explain something. That was very rare, and since I was better in that than other things, I started to do that. Many people joined the office with their own specialties: one was doing this, one was doing that.’

‘I think that was a deliberate idea of Rem, to have all these different people in the office and to assemble from all these ideas, rather than to shape everybody into one single system. I think that worked very well. I don’t know how it is now, but I think it worked in the beginning. It was really very successful because it also attracted people to participate.’

‘I had no experience before OMA, so I don’t know how it was done, but what I experienced in the beginning of the eighties—this way of doing things, having an open studio with teams and so forth—I see that back in all these OMA people and even in the second generation. I think it’s similar and I think it works very well because most of these offices are relatively successful. There must be something to it. It’s also a sort of collective authorship. Of course, Rem Koolhaas is the big author, in the sense that he was always steering it. So, there is a sort of hierarchy and there is Rem as the main motor. But at the same time, I think the team is a collaborative and collective work structure, with a sort of collective authorship. I must say, I always felt that I was part of the authorship, rather than that you work for somebody in the background.’

— Willem Jan Neutelings Transcript click here.