Schmitz and Drévet: The Egyptian Pavilions at the 1867 ‘Exposition Universelle’

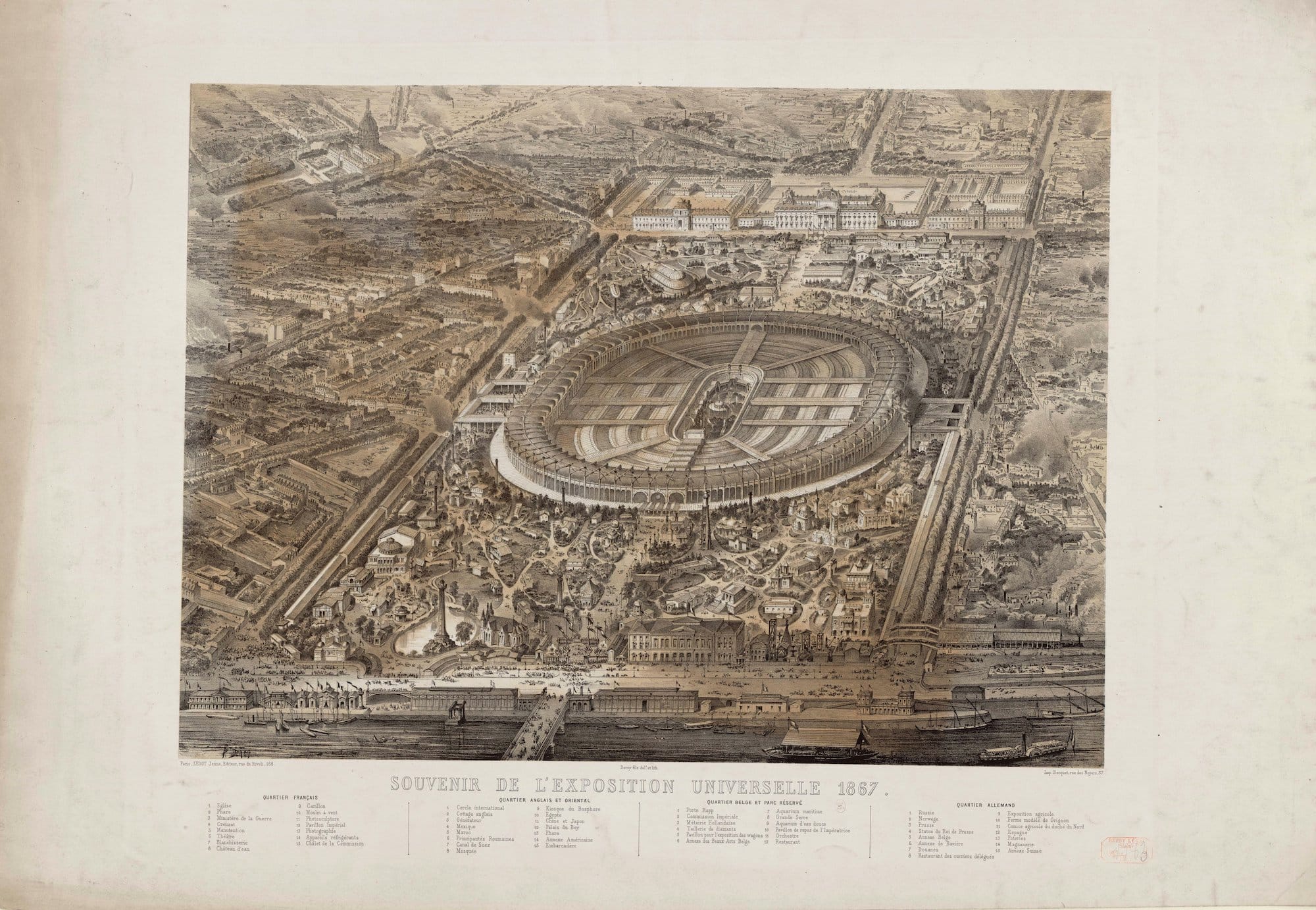

The 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle was one of the most frivolous and lavish events in late-19th-century European history. Erected along the Champs-de-Mars, it encompassed a huge, covered arena surrounded by dozens of pavilions and gardens.[1] It was conceived by Napoleon III to showcase of industrial and technological progress, to promote international trade and cultural exchange, while also celebrating achievements in science, industry, and the arts. One visitor to the exhibition, the perfumier Eugene Rimmel, likened it to a ‘seven months wonder’, lauding its brilliance and originality as evidence of the ‘natural progress of man’s genius.’[2]

An important aspect of the exhibition was the opportunity to study the cultures brought into contact with European powers through their colonial exploits. Another visitor to the exhibition, the English journalist, George Augustus Sala, described the variety of the displays in his dispatches to the Daily Telegraph:

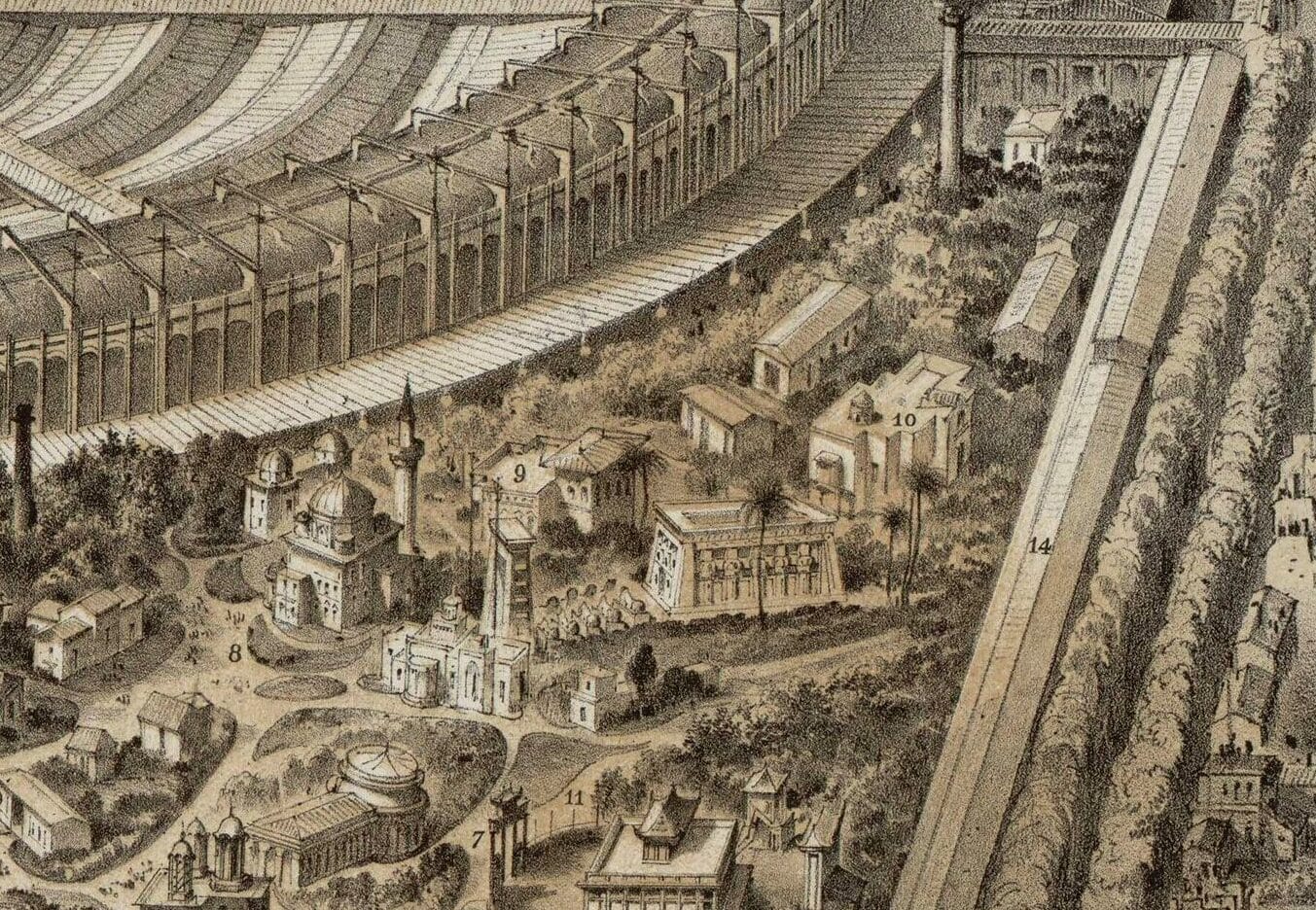

‘Egyptian temples, Turkish mosques, and Tunisian bazaars, lighthouses and laboratories, conservatories and aquaria, the picture-gallery and the lapidary’s workshop, the tavern and the theatre, the church and the coffee-shop, the Bible-stall and the showman’s booth, the toy-shop and the library, the stable and the labourer’s cottage—all the beautiful and curious and interesting objects brought together to the park must submit to one common lot, and come to one common end.’[3]

But this ‘common lot’ was not a neutral arena, and sections such as the Egyptian pavilion have been analysed by historians through the lenses of cultural othering, the trend of Egyptomania, and the ‘imperial gaze’. However, the Egyptians themselves were acutely aware of the political significance of the display, using it to position them strategically in terms of cultural, technological, and industrial relationships and to engage in diplomatic and geopolitical manoeuvring.

When Egypt was allotted around 6000 square metres in the ‘Oriental section’ of the exhibition in 1865, it was nominally still a province of the Ottoman Empire. At the time, Egypt was at the peak of its modernisation reforms and the Viceroy Ismail Pasha (r.1863-1879) seemingly embraced the opportunity to represent his county in Paris, hoping to shape Egyptian national identity.[4] As Sala described:

‘There was no mystery about Egypt’s place in the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1867. The energetic and apparently enlightened Viceroy spared no effort to glorify his dusky dominion in the eyes of the world in Paris. The countries generally assumed to be most backward in civilisation attempted to prove, so far as outward show and glitter went, in the Champ-de-Mars, that they were leading the van rather than bringing up the rear of the march of Progress. […] The Egyptian Viceroy ventured on a bolder geographical paradox. He strove to convince the Giaours that Egypt is in Europe.’[5]

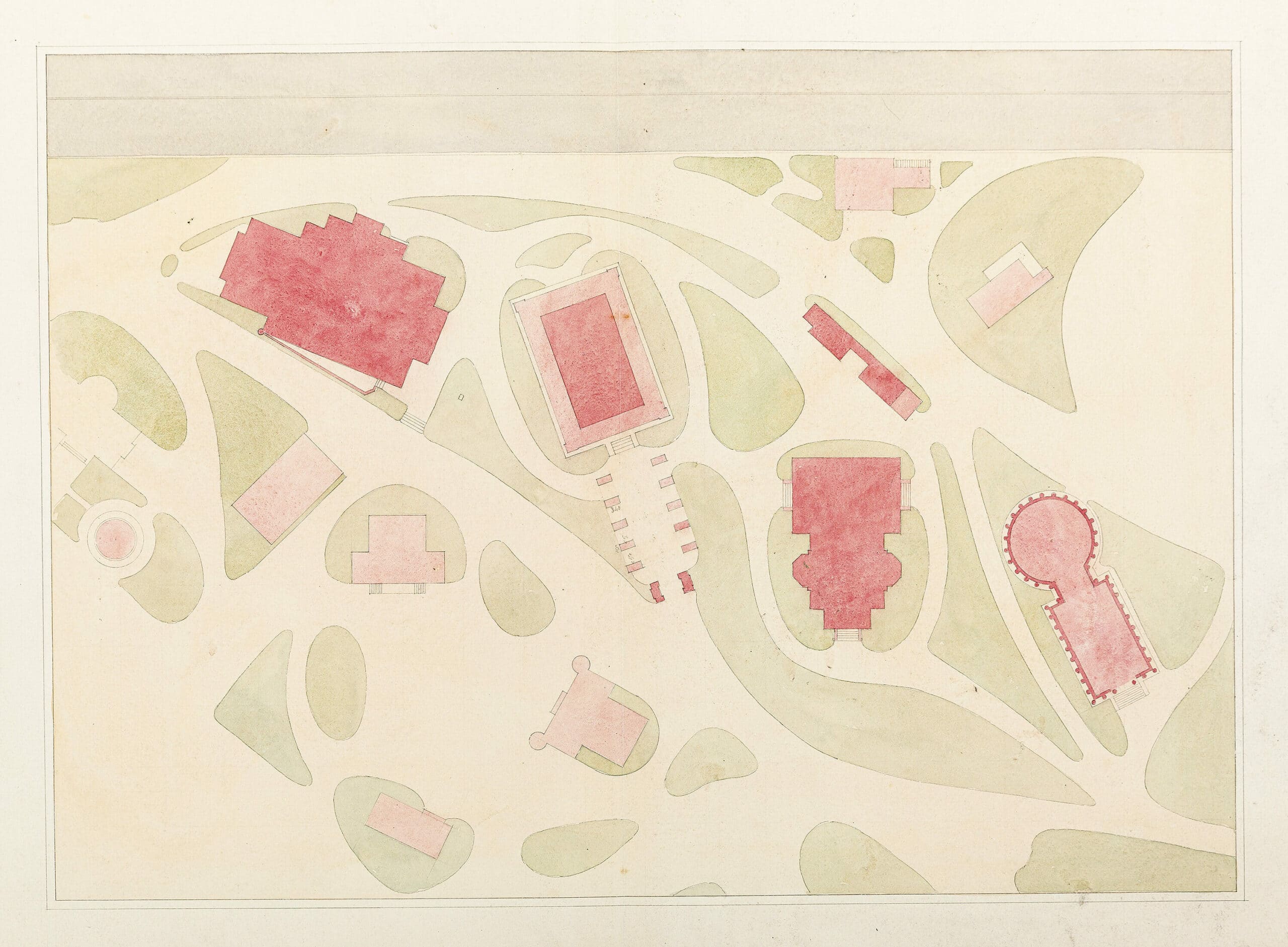

Recently, Drawing Matter added to its collection a large group of drawings by Édouard Schmitz and Jacques Drévet which includes material for several of the pavilions designed for the Egyptian section of the 1867 Exposition. Although he was chosen as the official architect for the project, Drévet had never visited Egypt, and so relied on the information and drawings made by Schmitz, himself a Frenchman based in Egypt.

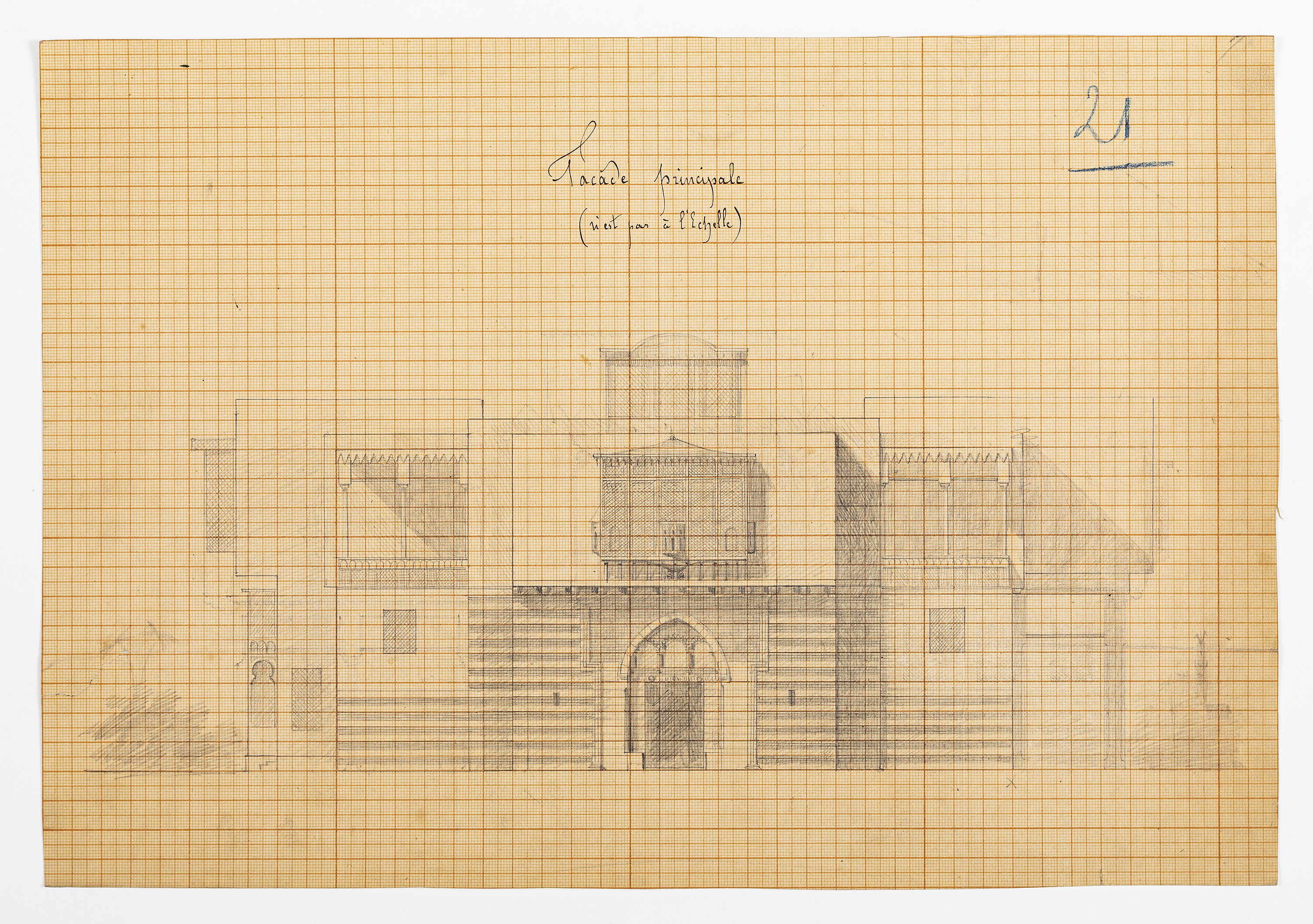

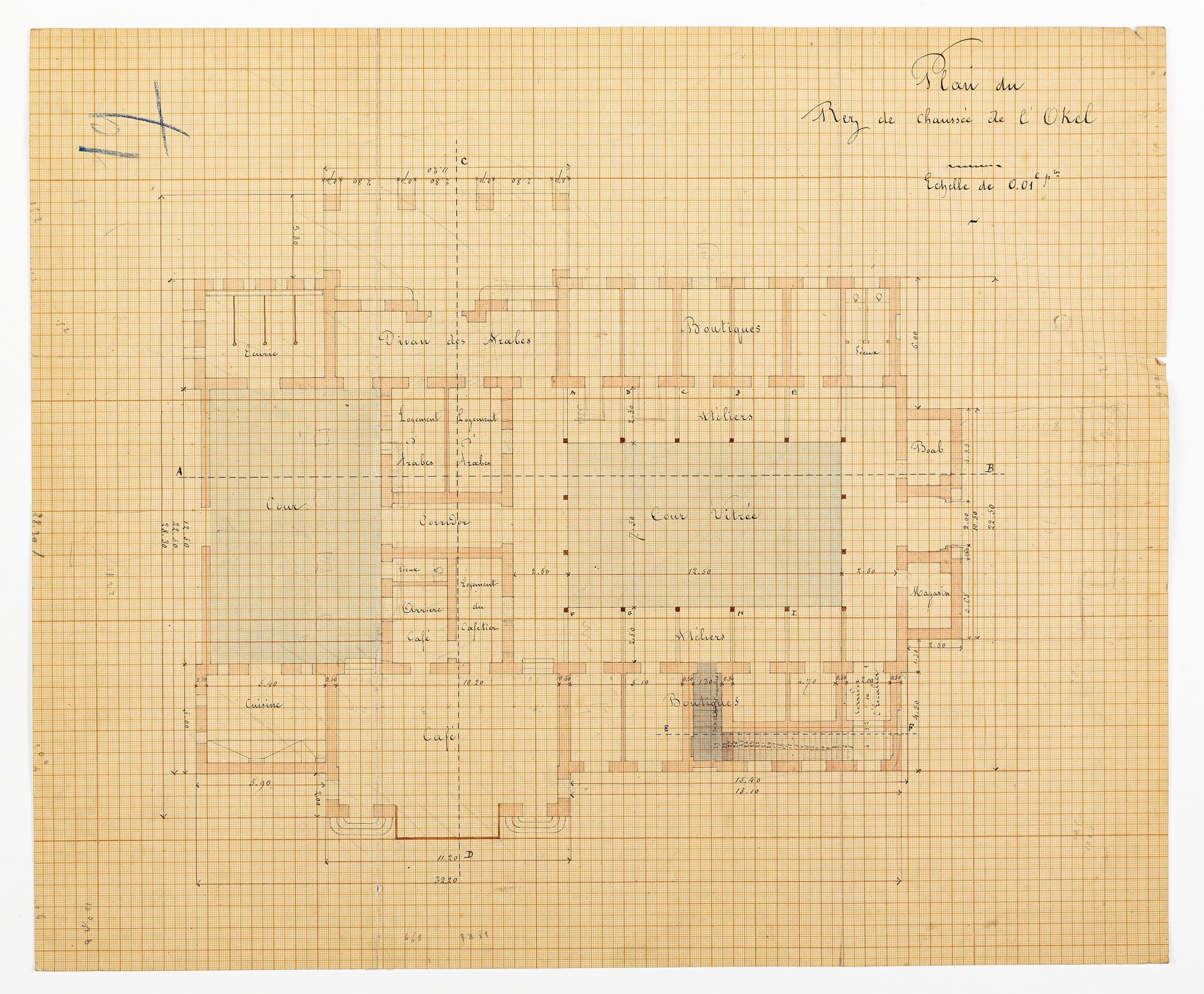

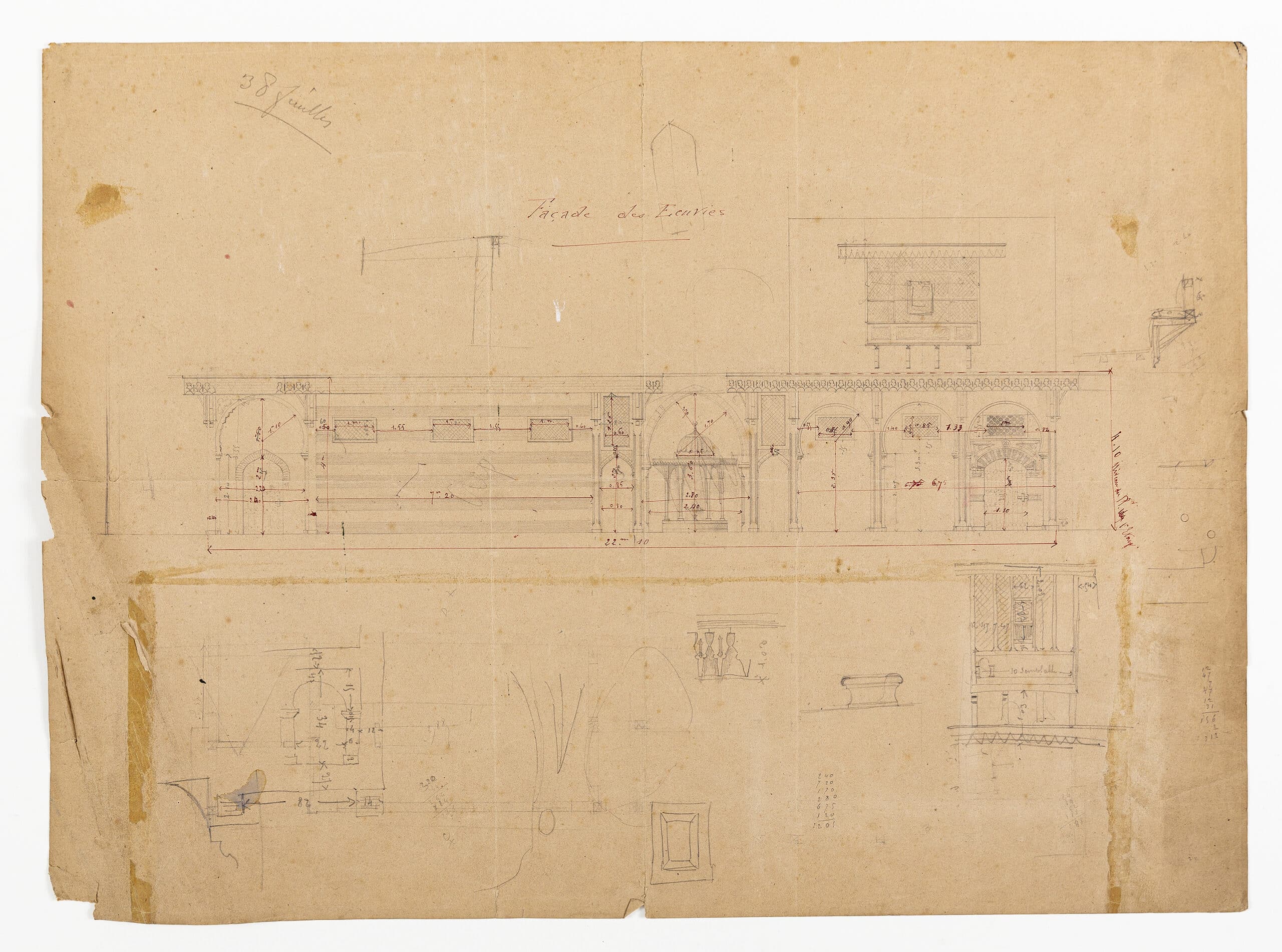

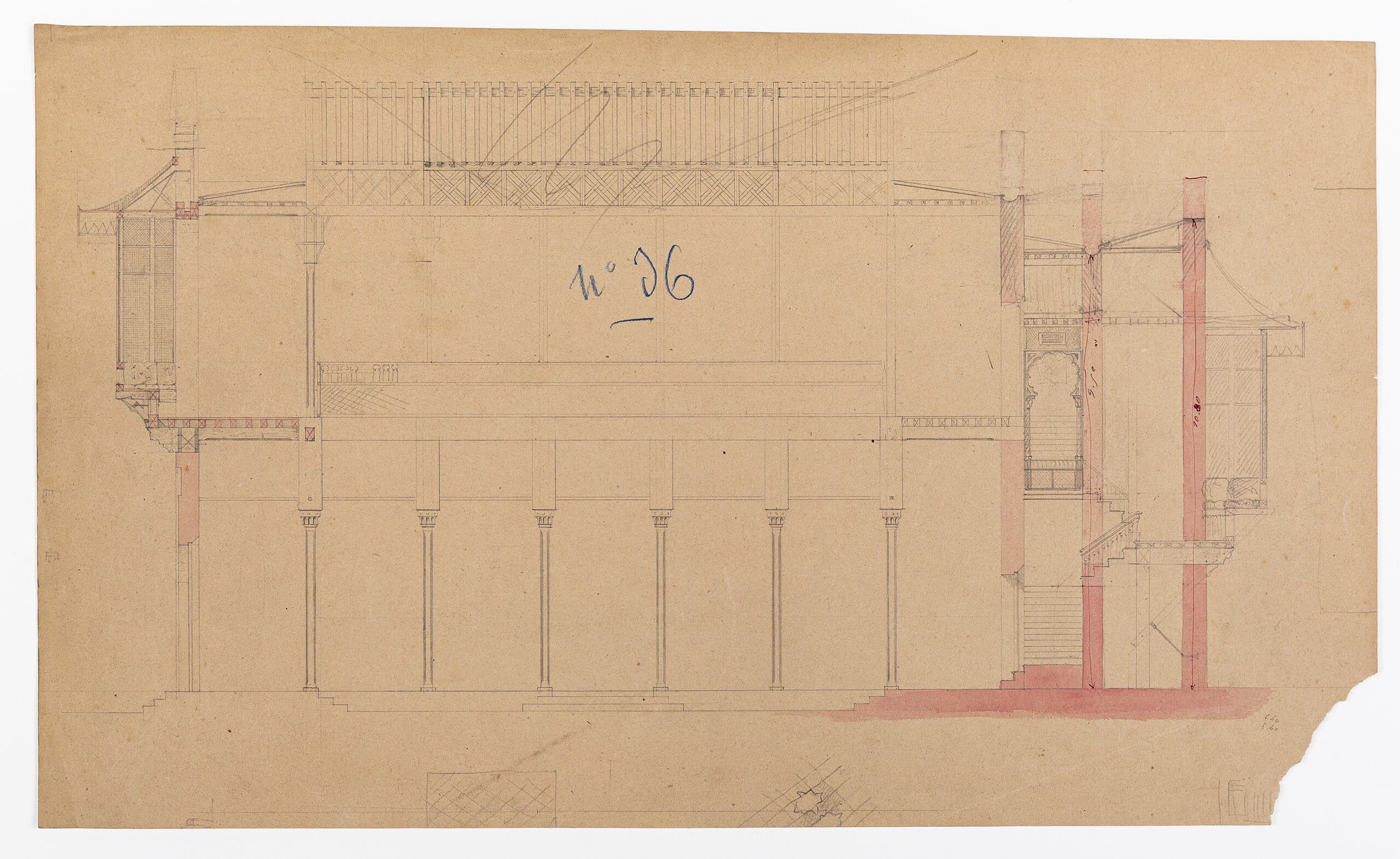

The Egyptian section aimed to represent thousands of years of Egyptian history in four main buildings: the Temple was home to an extensive museum, the Selamlik (Viceroy’s Palace) contained rooms of the Viceroy and exhibited a relief map of Egypt, the Okel (caravanserai) housed a public café, rooms for the Egyptians brought to France to exhibit their crafts, an anthropological exhibition, and the stables showed dromedaries and donkeys. The nearby Isthmus of Suez pavilion meanwhile represented the massive engineering project that was in the process of being constructed at the time, further illustrating the close ties between Egypt and France.

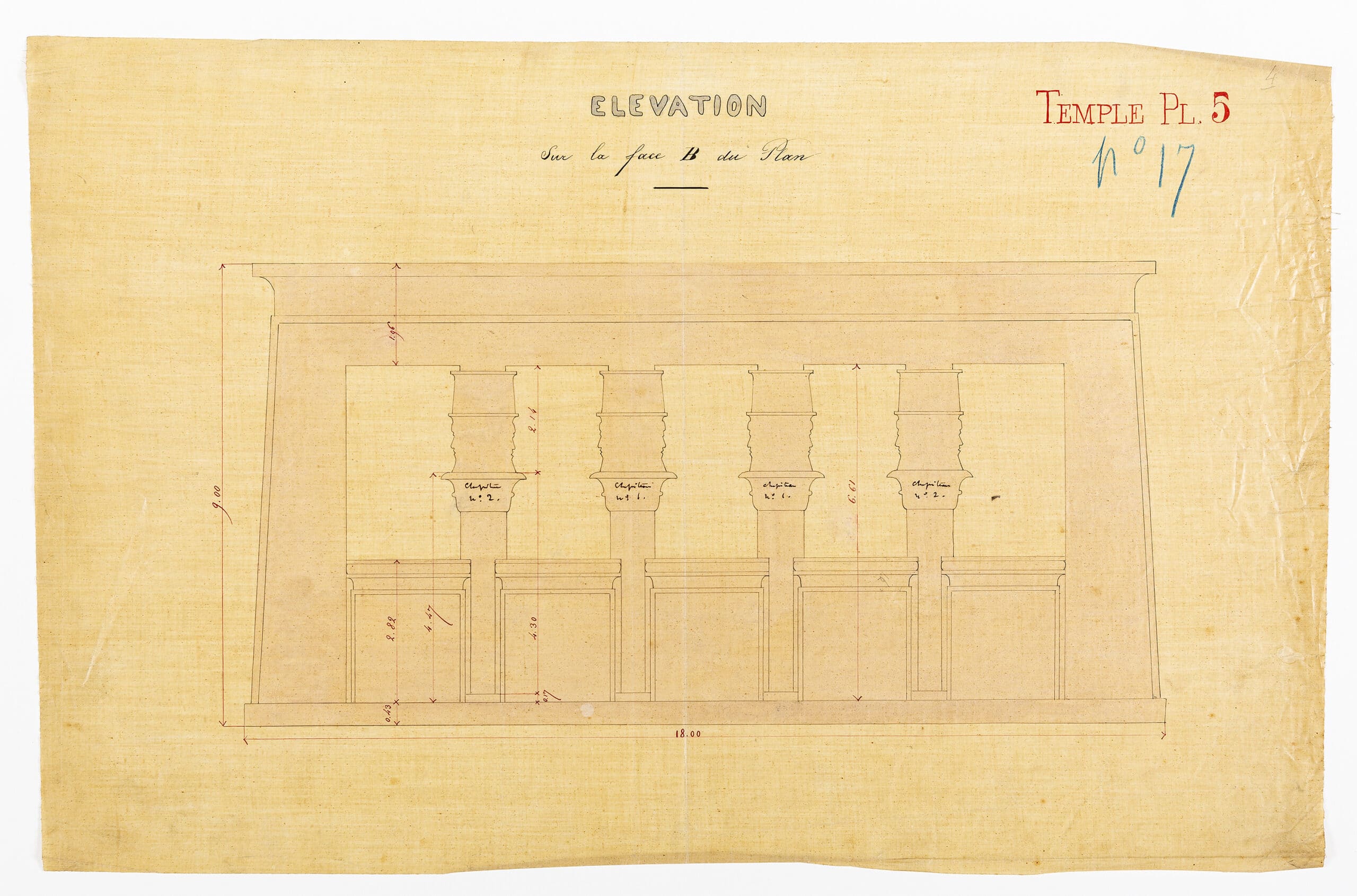

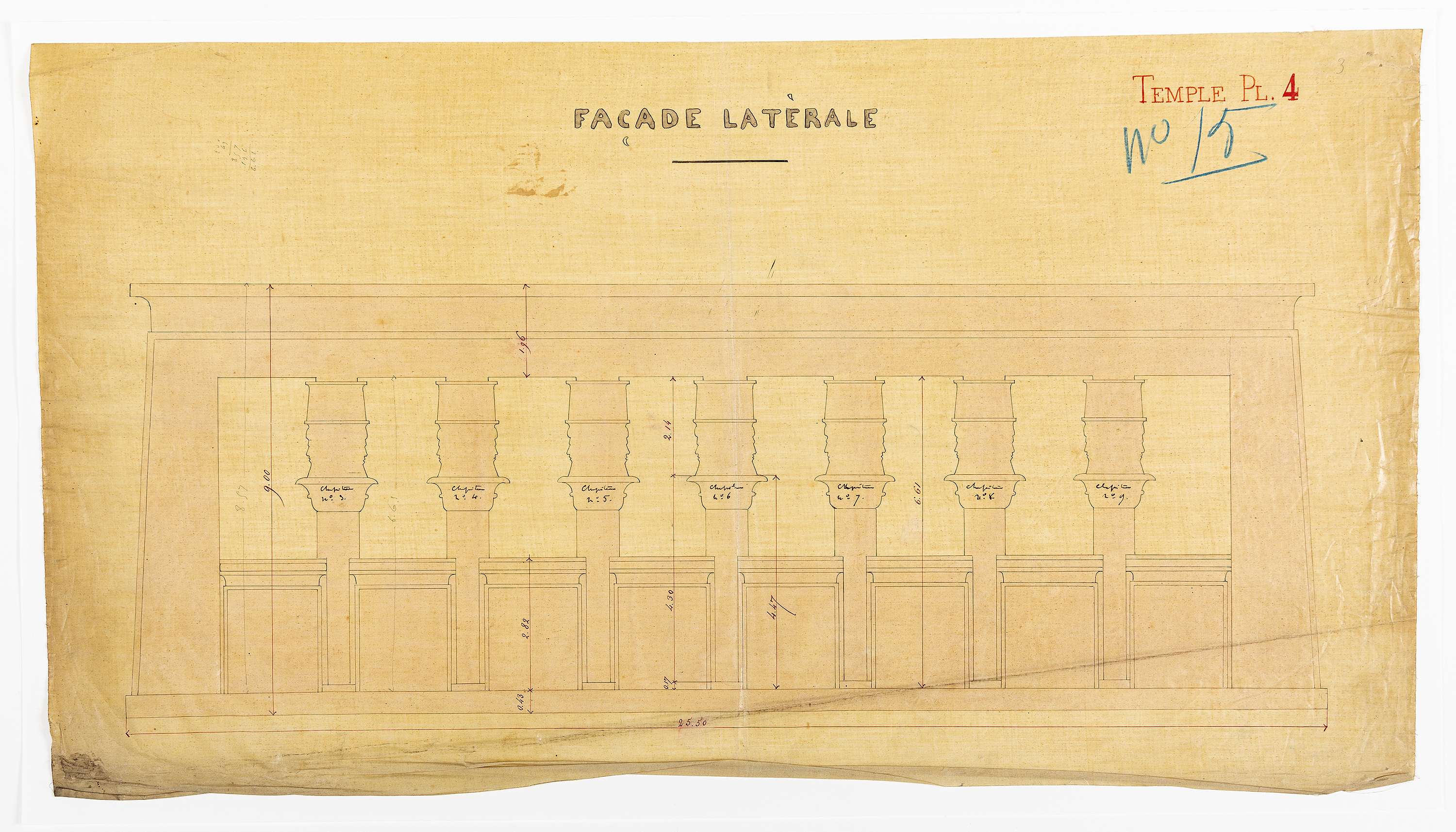

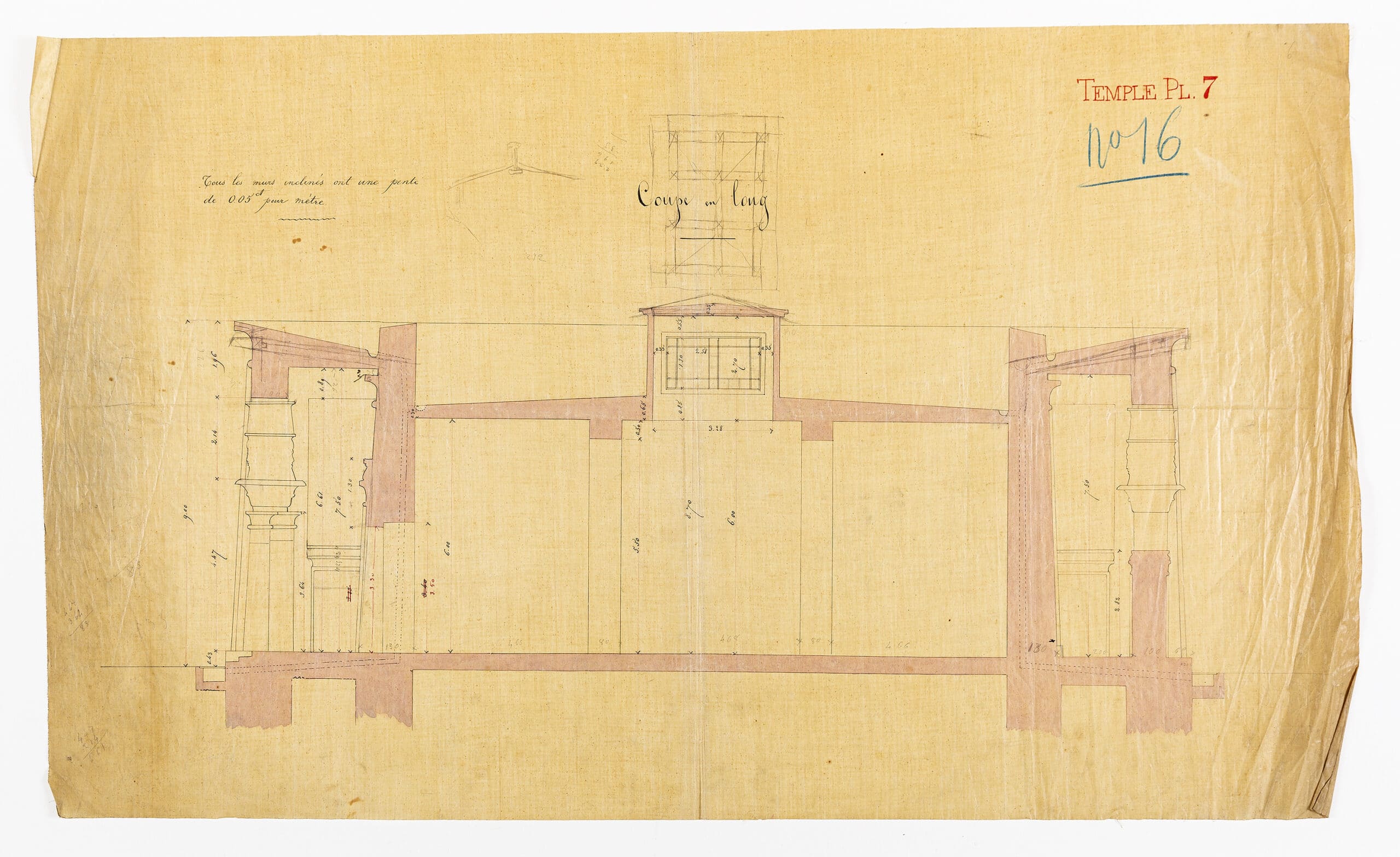

The Temple

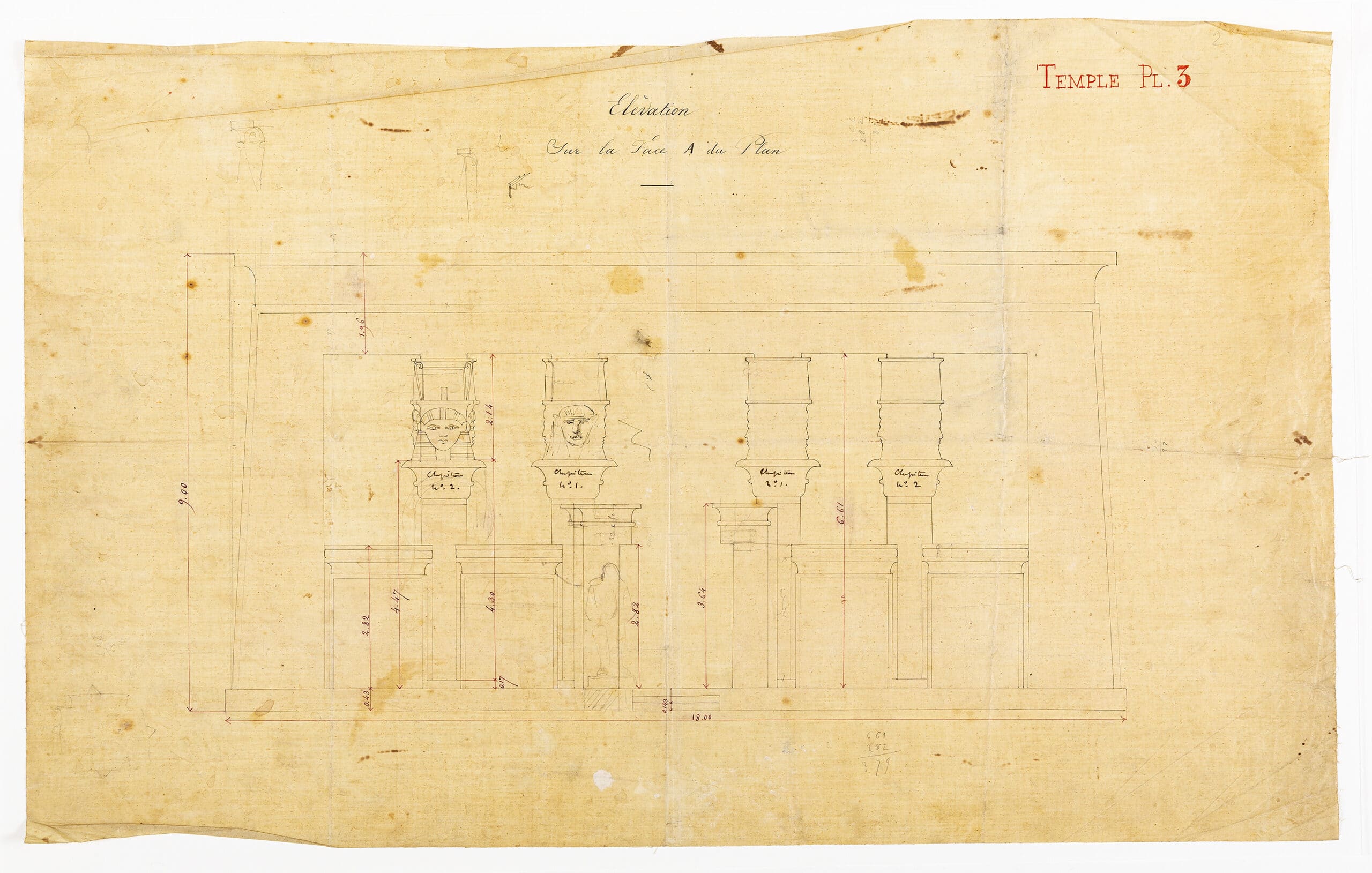

The pharaonic temple positioned Egypt as the cradle of civilisation, combining the most brilliant periods of the Pharaonic architecture and lessons from Egyptian archaeology.[6] The building was a partial replica of Emperor Trajan’s temple at Philae, but rather than being an exact copy, it was a Western eclectic study summarising various Egyptian artistic traditions in one model.[7]

Adorned with hieroglyphs, the temple included a central chamber (Secos) and was surrounded by an exterior gallery supported by colossal, decorated columns that blossomed into lotus flowers. The archaeologist Auguste Mariette, who had been employed as General Commissioner of the pavilions, explained how the temple gives the visitor an idea of what Egypt was like in its three characteristic periods: the interior rooms represents the oldest era contemporaneous with the pyramids, the exterior walls reference the art of the New Empire (of Seti and Ramses) and the decoration of the colonnades was borrowed from the reign of the Greek successors of Alexander, the Ptolemies. An avenue of sphinxes, preceded by a Pylon, led to the entrance of the temple. Made according to custom, there were two seated sphinxes to each side of the temple door facing the visitor. The Pylon, a triumphal arch over eight metres high, was ornamented with a solar disc between two vipers and emblems of the south and the north.[8]

The temple was, above all, a museum that exhibited a variety of antiques. It offered a diverse sample of Egyptian Art from the Bulaq Museum, notably the jewels of Queen Ahhotep (reportedly catching the eye of Empress Eugénie who asked to keep them).[9] Rimmel vividly described the collection in his notes:

‘In the interior has been placed a very interesting museum, contributed by the beautiful, Boulak collection, and continuing several statues prior to the time of Phidias. […] One of the most curious objects in this museum is Queen Aah-Hotep’s jewel-case, discovered at Thebes by Mr. Mariette, the indefatigable explorer. It contains golden bracelets ornamented with figures engraved on a turquoise-blue ground, necklace with symbolical signs and flowers, and a supple chain of admirable workmanship, to which a suspended three golden bees. […] We also notice, as being very interesting, three gold hatchets, and six silver ones found in a royal tomb, a beautiful poniard formed of four female heads, enriched with lapis-lazuli and cornelian, a dark bronze blade covered with inscriptions and inlaid with flowers, and a Queen’s diadem ornamented with sphinxes.’[10]

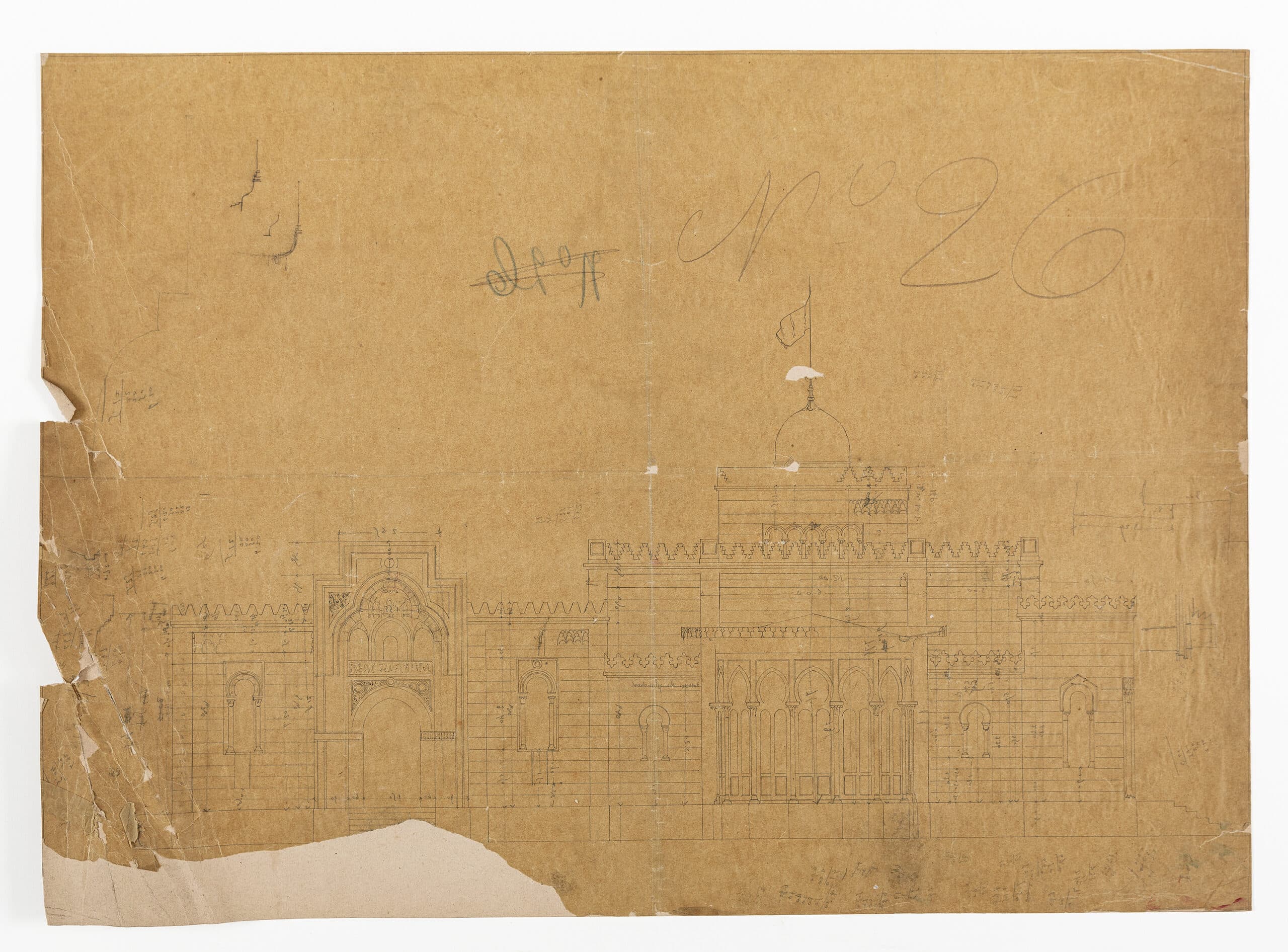

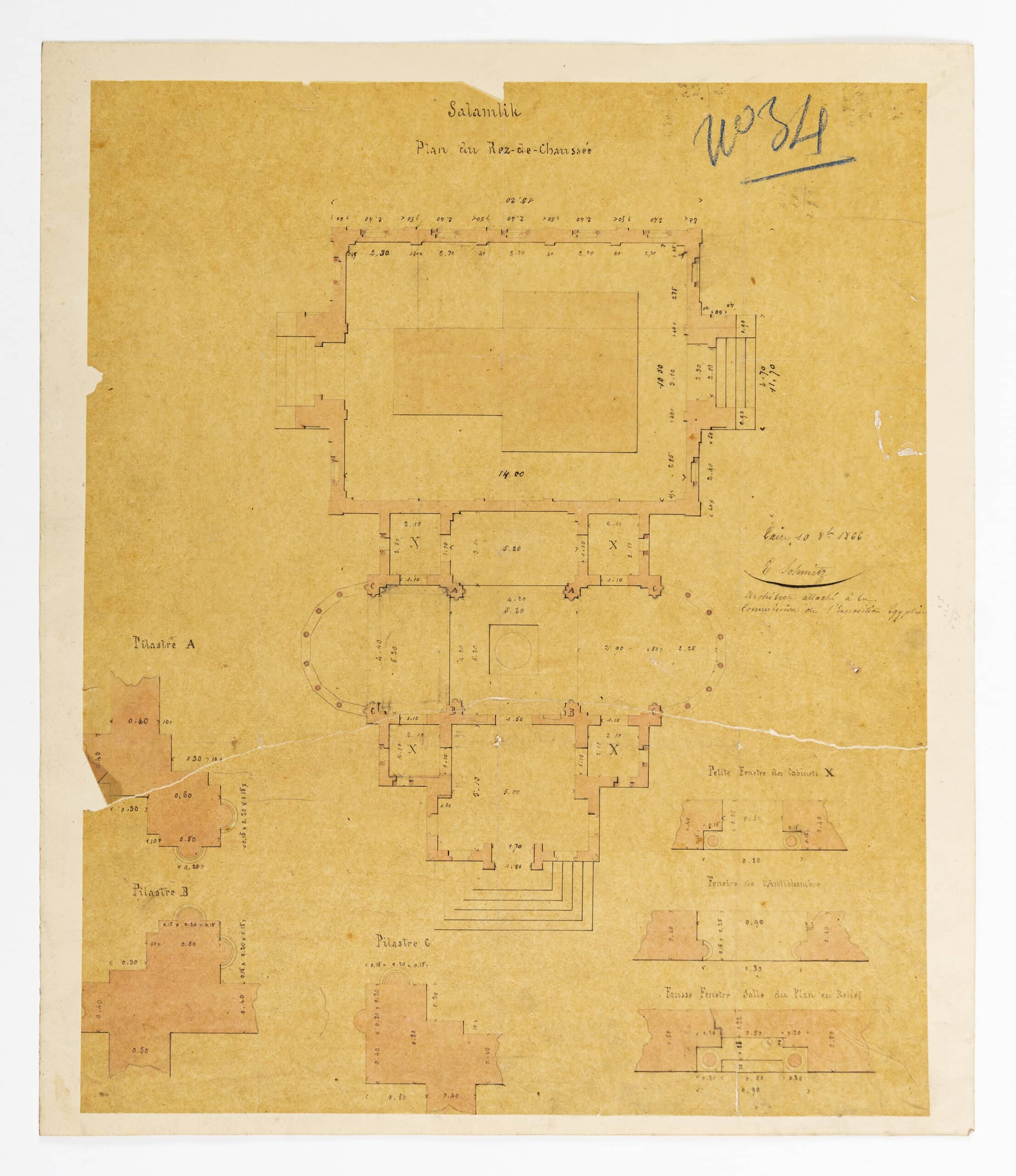

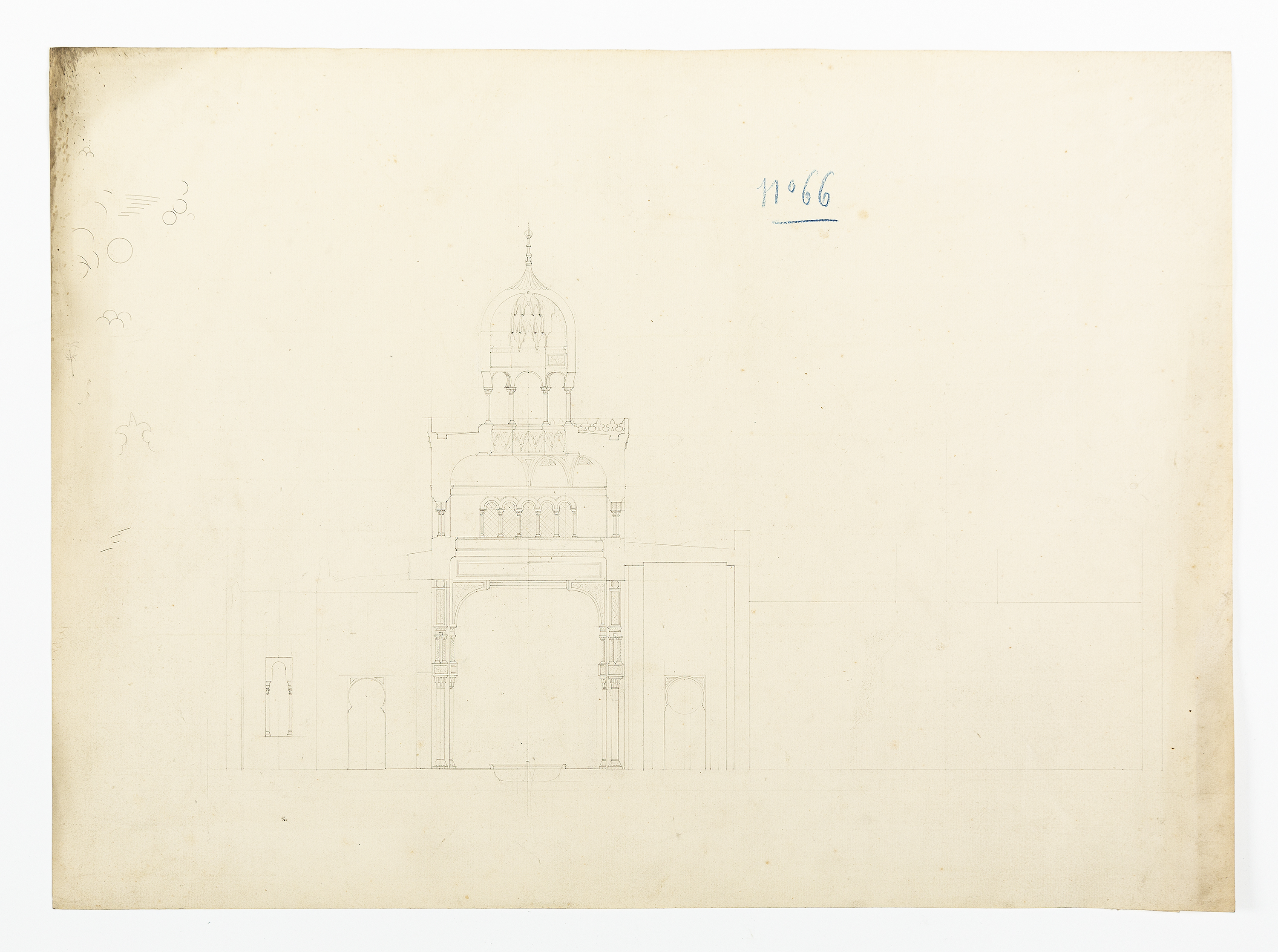

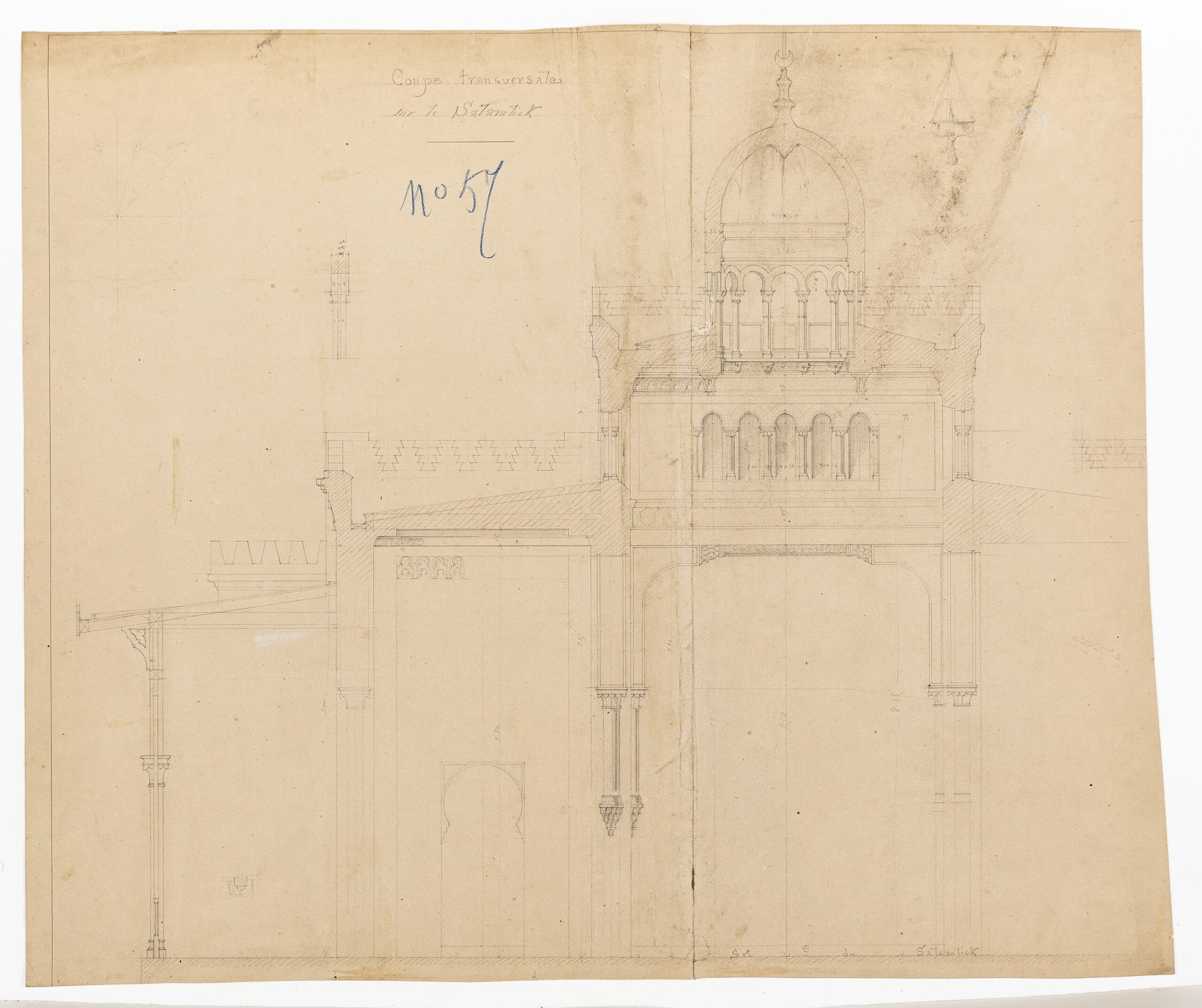

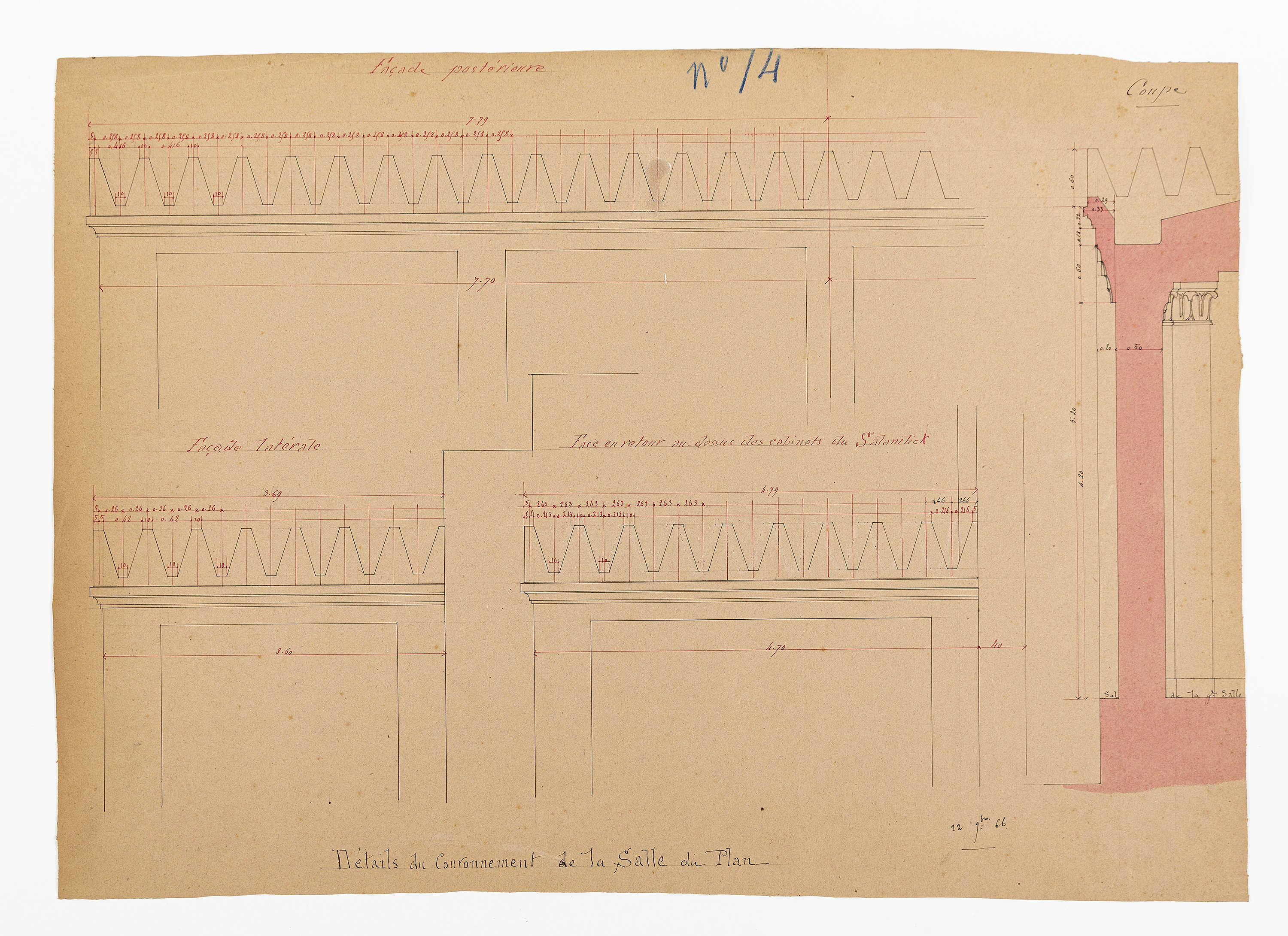

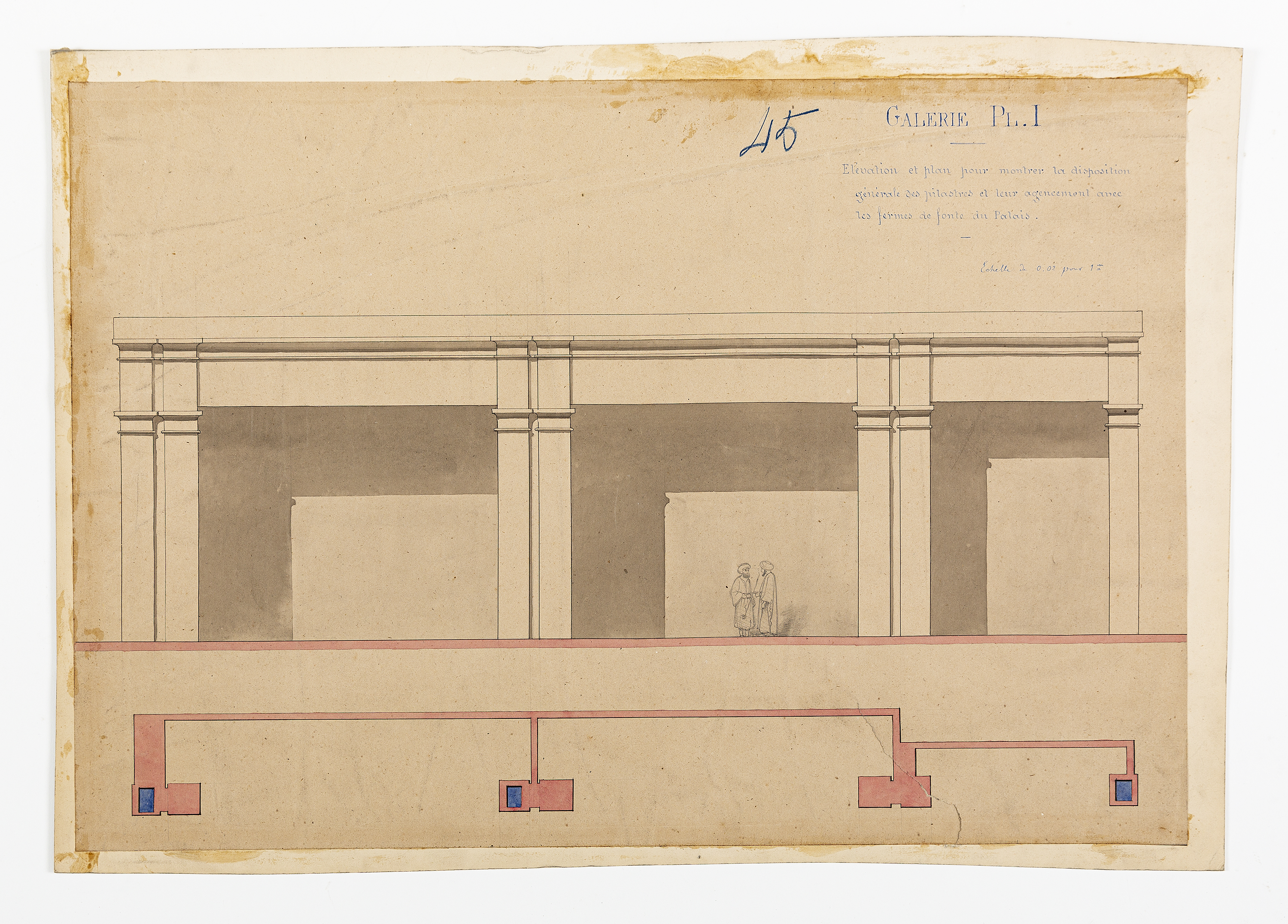

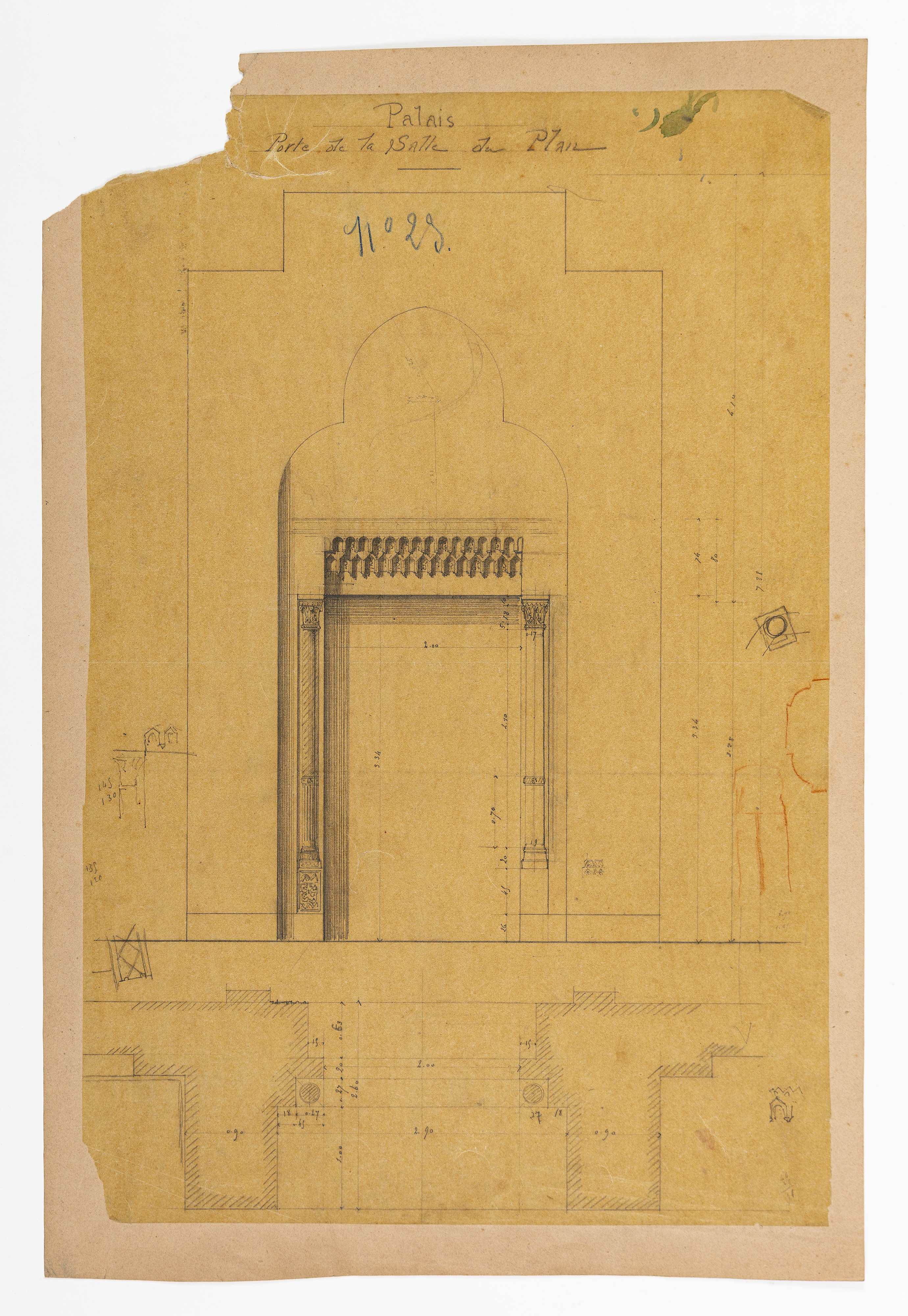

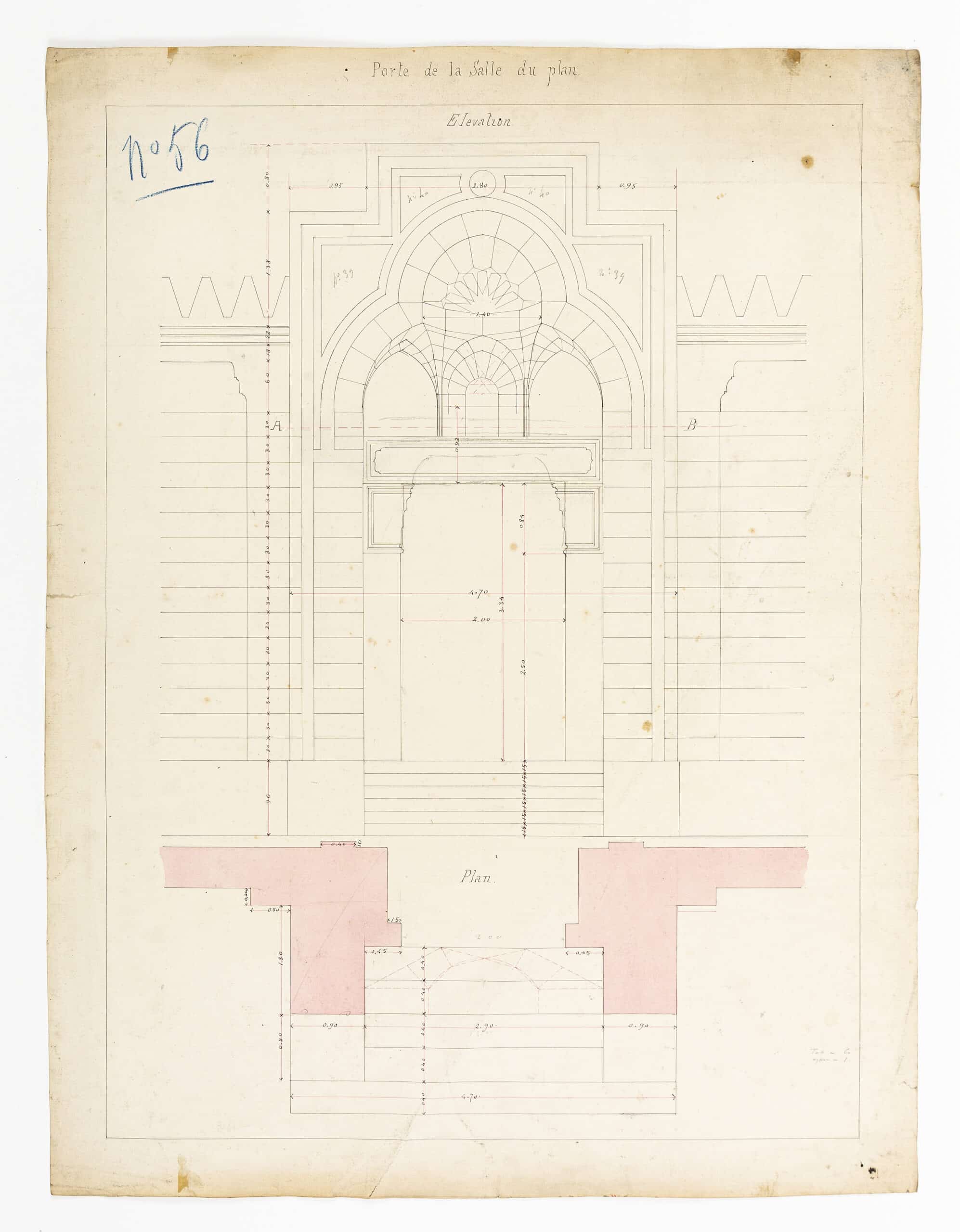

The Selamlik

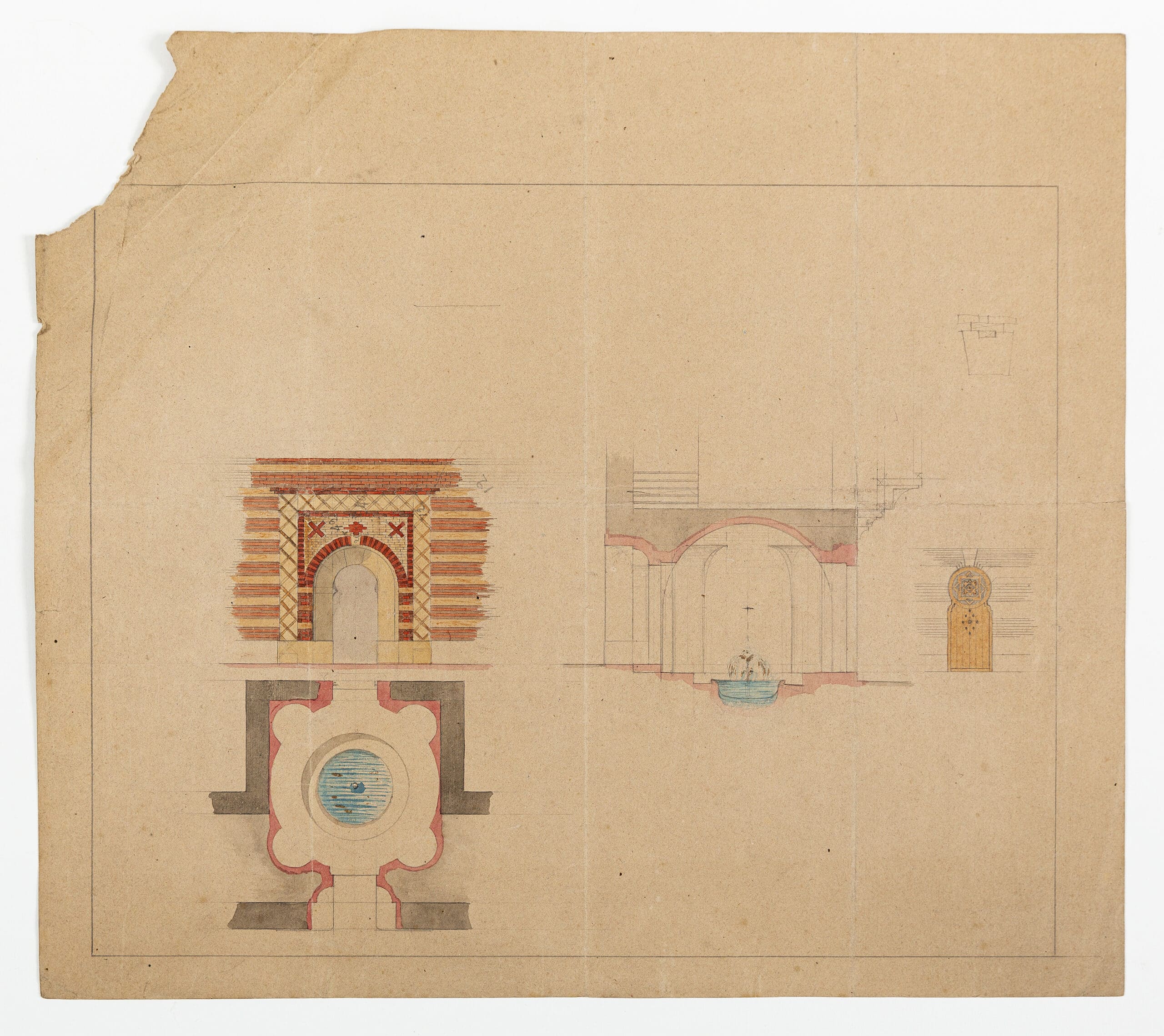

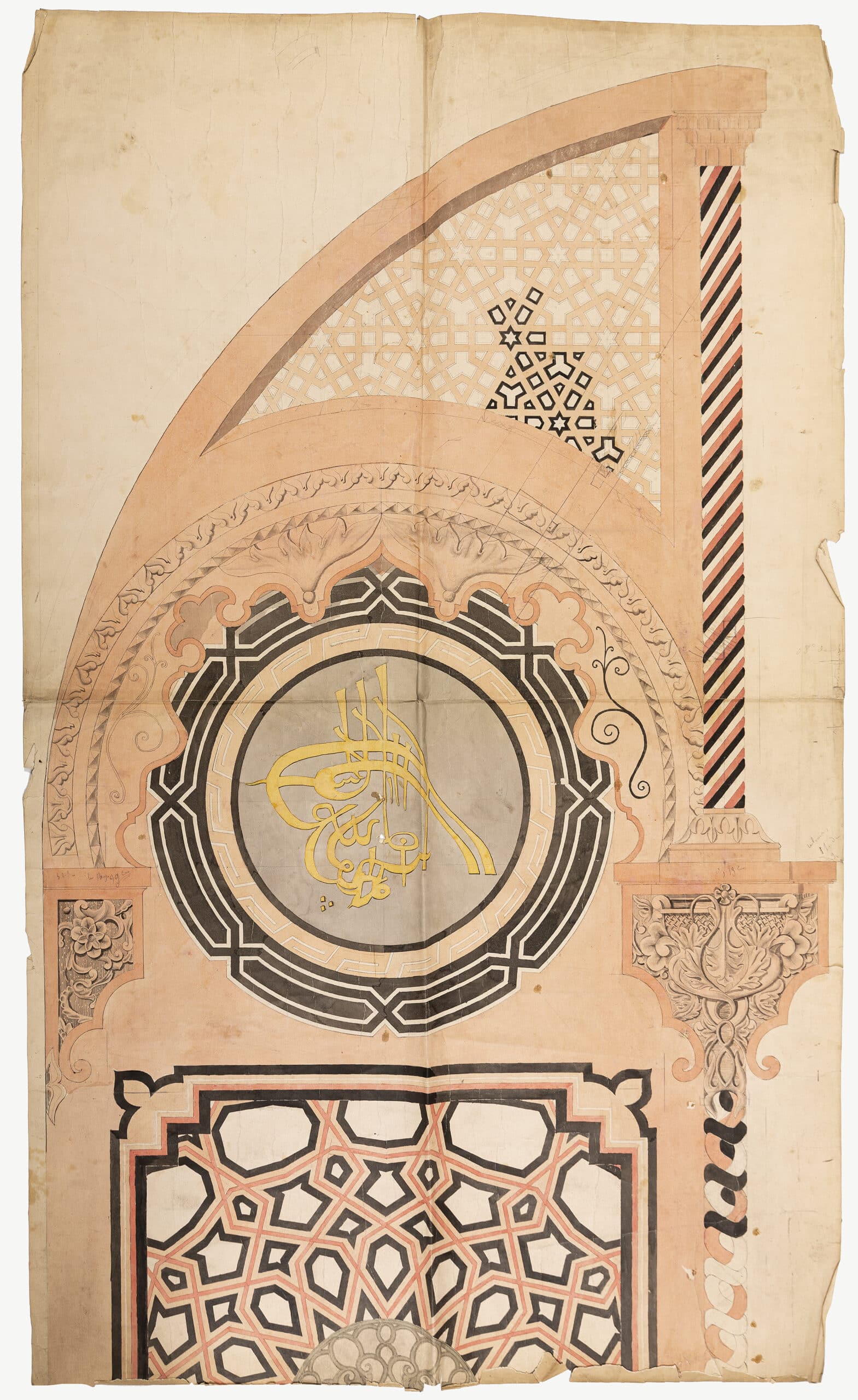

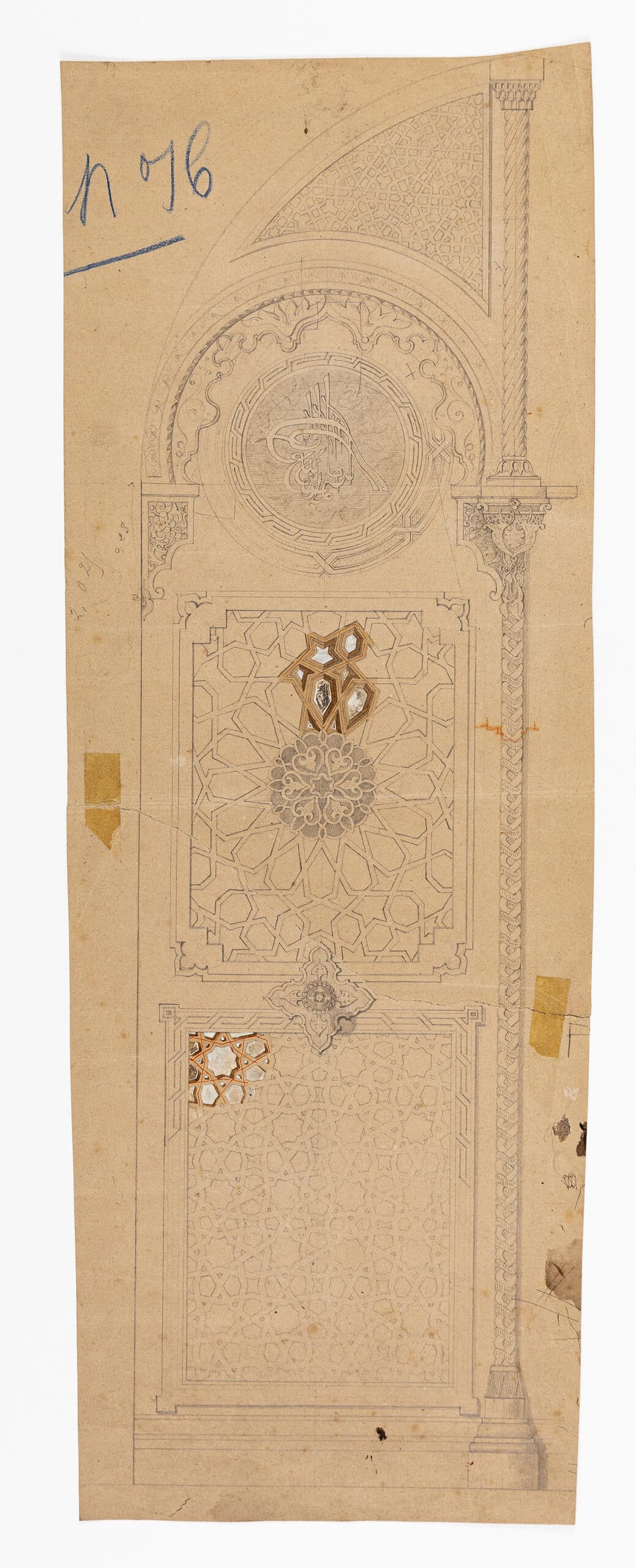

The Selamlik represented Egypt’s Islamic civilisation with a secular building made from wood and plaster, decorated with blue and red bands on a white background and surmounted by a cupola. The building was designed by Schmitz, while Drévet was responsible for the interior decorative scheme, including mosque lamps, a gold crescent at the top, a fountain in the centre, and arabesque ornaments. The Viceroy specifically requested the arabesque ornaments to be reproductions of those in the Gamalieh palace where he was born—an explicit sign to legitimise his dynasty as the heir of the Islamic tradition.[11] The building, ‘full of grace and lightness’, had numerous doors carved into niches, graceful domes in azure and gold, and wooden rotundas decorated with stained glass stood out on the side.

The explicitly political display inside the Selamlik underscored the country’s revival and modernisation which started under Ismail’s grandfather Muhammad Ali. This was also reflected in several relief maps of Lower and Middle Egypt, as well as a plan of Alexandria commissioned by the Viceroy. The reliefs exhibited the natural features of the country and its wealth of geological resources.[12]

The Selamlik also housed private apartments for the Viceroy and the highlight of Egypt’s presentation was Ismail himself. In the Selamlik, where he had private rooms to rest, he was seated on a divan ‘smoking from his long Oriental pipe’, graciously welcoming notable Parisians with ‘the charm of his serious and fine spirit’. Among his guests were the French Emperor and Empress and the Imperial Prince, who toured the exhibit with Mariette.[13]

The Okel

Located behind the temple, the Okel represented contemporary Egypt and its industry. The building was designed for visitors to encounter ‘Egypt’s living types’ as Gabriel Richard noted in his L’Album de L’Exposition Illustrée. Designed by Drévet based on Mariette’s suggestions, the two-storey building was recognisable from afar, designed after prototypes in Aswan and was composed of mashrabiya screens, doors, ornamented ceilings, and arabesques.

Covered galleries ran around the building where merchants from Cairo were installed and set up their trades: they offered rich foods, precious gems, brilliant carpets, and all kinds of ‘Oriental curiosities’ for sale. Egyptian artisans demonstrated different crafts, sold them in the shops and there was a café offering complimentary coffee, a chibouk (a Turkish tobacco pipe) and shisha (water pipe) to visitors. Rimmel describes a barber who was ‘shaving his countrymen in true Oriental fashion’:

‘Among those artisans one who attracts a great share of attention, is the turner, a grave old man, who slowly guides with his left toe the blade of the lathe, whilst he wields with his right hand a bow which causes it to revolve. A more primitive apparatus it is impossible to imagine; it has probably been handed down from father to son since the time of the Pharaohs.’[14]

Perfumery and cosmetics were Rimmel’s area of expertise. His detailed descriptions allow for an immersive journey back to the 19th century certainly convey his interest:

‘by the side of fine cosmetics, such as kohl, a black powder, which is employed by the modern as it was by the ancient Egyptians for the purpose of making the eye appear larger, and adding to its brilliancy; henné, which is used to give a roseate hue to the finger, and Schnouda to raise a transient blush on the cheek, we see the dilka or ostrich grease, with which the Nubians anoint their whole body until it shines like a well-polished book; the crocodile glands, which do service for must in the Sennar, and the aromatised cocoa oil, which is carried about by wandering tribes in an ivory horn.’[15]

The upper floor was an anthropological gallery, organised by Mariette. Over 500 skulls and half-a-dozen whole mummies that were unravelled in several sessions, were on display. The mummies were already in sarcophagi and only intended for the study by anthropologists who had to request access through Mariette. The skulls were classified by dynasty and location. Mariette declared proudly that ‘nobody could fail to see the service which such a considerable collection of material can render to the science of anthropology.’[16]

Praised as ‘the most splendid and the most complete’ display, the Egyptian pavilion attested to Ismail’s success in positioning his country as heir to the glorious Pharaonic and medieval Islamic civilisations as well as a modern, civilised, and secular state. The French press proclaimed that Egypt could ‘be among the most civilised countries in Europe’ and the Suez Pavilion firmly reinforced this sentiment. After the Exposition, however, it became increasingly clear that Ismail’s accelerated modernisation programmes came at a great price: the country was in enormous debt leading to the establishment of Dual Control by Britain and France. And though the splendid displays and buildings at the Paris Exposition were framed as optimistic, cultural celebrations and national self-definition, it is fitting that Charles Edmond ended his account of the Exposition with a warning: ‘we must not forget that (…) the earth does not always shine with the same brilliance, and, while humanity is eternally young, people age.’[17]

To explore the more drawings by Schmitz and Drévet for the 1867 Exposition, register for the Drawing Matter catalogue here.

Anja Segmüller was one of Drawing Matter’s interns this summer. She is studying BA History at the University of Oxford.

Notes

- Bela Menczer, ‘Exposition, 1867’, History Today, 7 (1967), 433–4.

- Eugene Rimmel, Recollections of the Paris Exhibition of 1867 (London: Chapman and Hall, 1870), 1.

- George Augustus Sala, Notes and Sketches at the Paris Exhibition (London: Tinsley brothers, 1868), 22.

- Alia Nour, ‘Egyptian-French Cultural Encounters at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867’, MDCCC 1800, 6 (2017), 35.

- Sala, ibid., 42–3.

- Nour, ibid., 43.

- Hippolyte Gautier, Les Curiosités de l’Exposition Unvierselle de 1867 (Paris: Delagrave et Cie, 1867), 28.

- Gautier, ibid., 57–8.

- Nour, ibid., 43.

- Rimmel, ibid., 240–1.

- Nour, ibid., 45.

- Gautier, ibid., 58–9

- Nour, ibid., 47.

- Rimmel, ibid., 238.

- Rimmel, ibid., 245.

- Auguste Mariette, Exposition Universelle de 1867: Description du Parc Égyptien (Paris: Dentu, 1867).

- Charles Edmond, L’Égypte à L’Exposition Universelle de 1867 (Paris: Dentu, 1867).