Jessie Brennan

An image

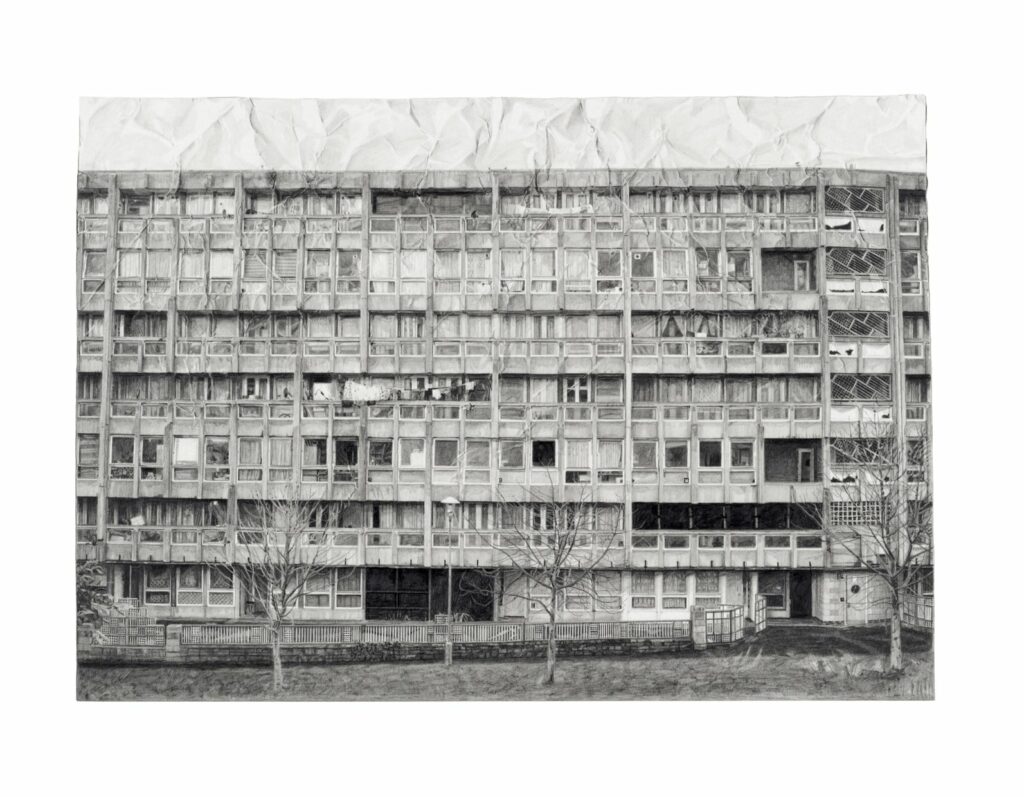

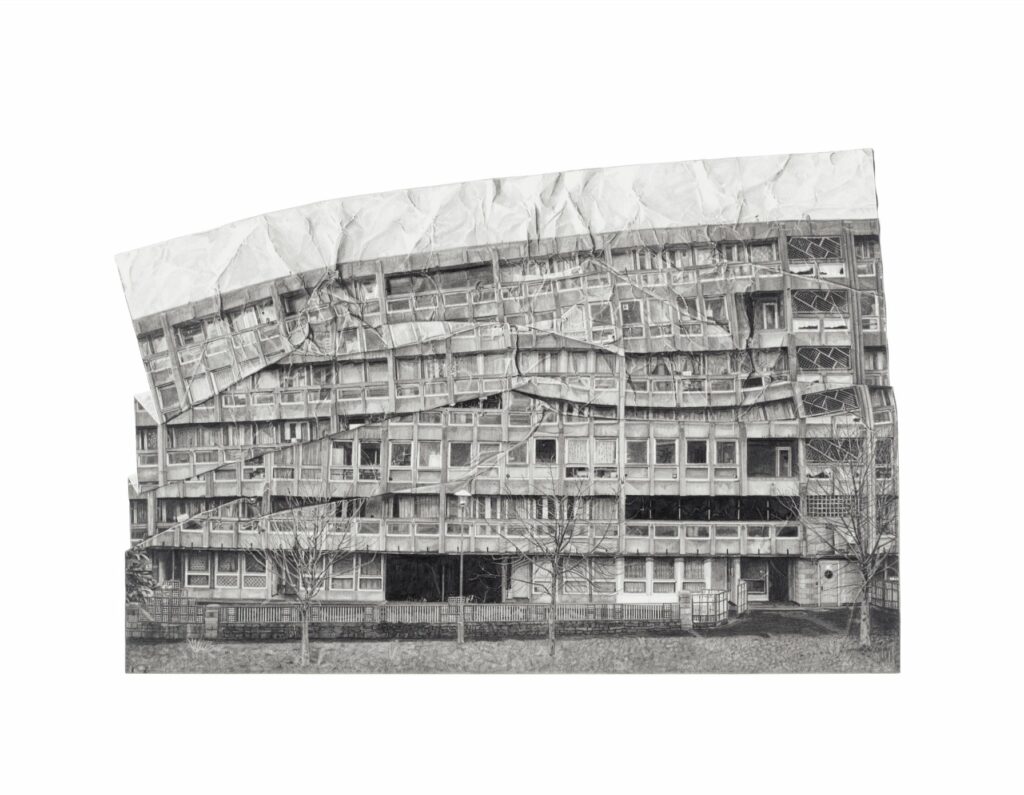

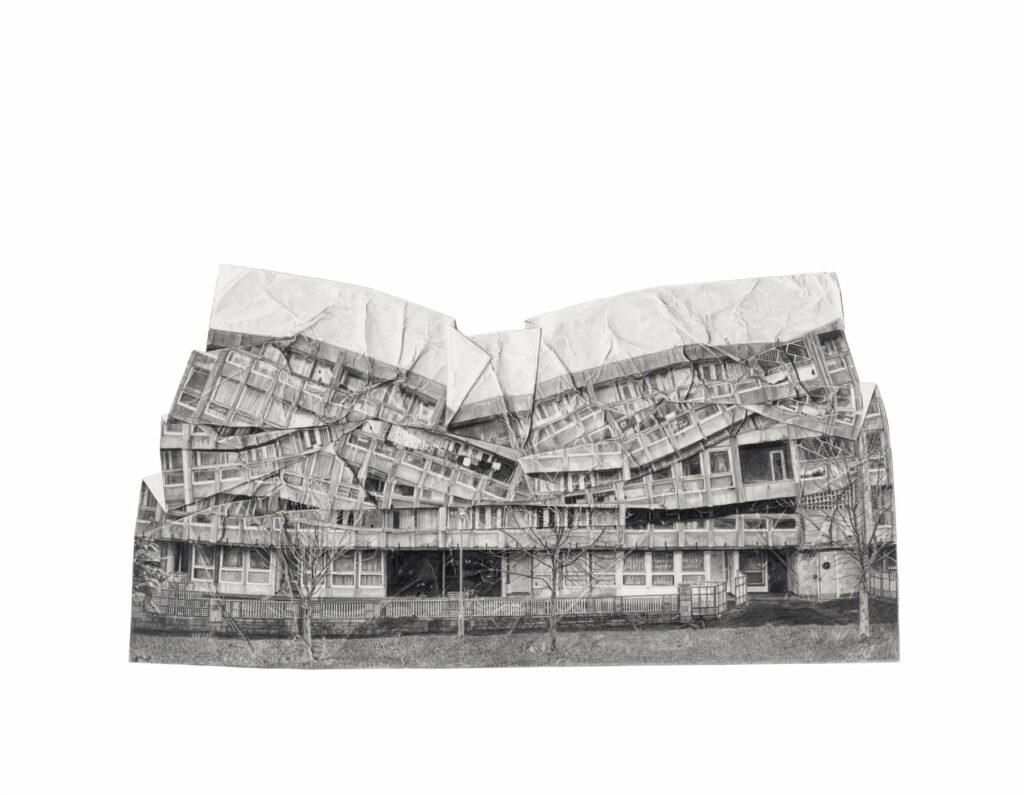

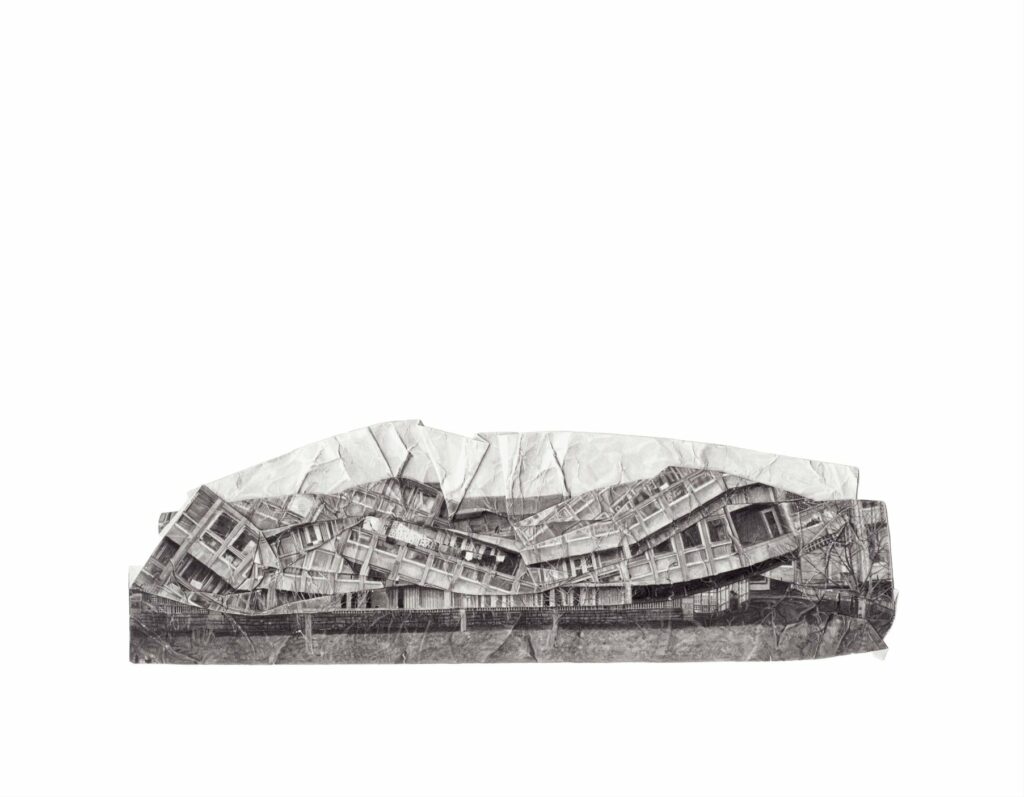

These drawings are an act of imagination. Like stills from the filmed footage of a detonation, in each frame a building slumps further down the viewfinder: present, going, going… gone.

Or so it seems. On closer inspection, it emerges that the building is still there. It is in fact a piece of paper bearing an image of the building that has been crumpled, crushed and compressed. It is only a visual conceit that has reduced a seven-storey structure to the point of flat-lining. It is not the architecture but its image that is dead.

A practice

The technique, in pencil on paper, is so meticulous that it appears to aspire to photographic reproduction. Across the grid of the elevation, every particular is given: curtains, blinds, net, lace, blank windows, washing lines, concrete, glass, air. It produces an image that does not occur naturally in human perception. Such a level of detail sustained over every part of the subject creates an impression of hyper-reality.

This documentation of minutiae could seem obsessive and impersonal, but there is tenderness in the smooth application of the graphite that transforms cold accuracy into humane attentiveness. The delicacy of the marks makes us alert to every element that they represent. There are innumerable textures, infinite tones of light and shade. This is worth looking at. We become aware we are contemplating a still life and, moreover, a vanitas.

A record

The series visualises the destruction of Robin Hood Gardens, Poplar. Designed by Alison and Peter Smithson in the late 1960s, the flats were slated for demolition commencing in 2015. At the time of writing, the process has not yet begun. By documenting the appearance of one section of the building, the first drawing – ‘The Order Land’ – is effectively a traditional, if partial, record drawing. The subsequent three drawings purport to record – but they bear witness to the performance of destruction rather than its reality.

Record drawings are Janus-faced. They document the status quo because of an unknown future. Although they are inherently retrospective, record drawings also imply something yet to come. The second, third and fourth drawings of this series – ‘The Scheme’, ‘The Enabling Power’, ‘The Justification’ (titles referring to the Compulsory Purchase Order issued by the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in 2013) – make this manifest.

In these record drawings, the genre’s pivotal position between retrospection and prospection is accentuated. Although the four images apparently show the destruction of Robin Hood Gardens, when viewed in reverse, they suggest its resurrection. A crumpled drawing can be unfolded in a way that a lost building cannot be restored. The series reflects on the documentary potential and purposes of record drawing itself.

A provocation

The Smithsons designed a high-rise, high-density social housing scheme that would incorporate the humanising elements of a traditional city street. It embodied a belief in social and architectural progress. Now the site is scheduled for demolition and redevelopment, which will result in the displacement of council tenants in favour of private owners who can afford luxury apartments. Objections to such social cleansing have proved as ineffective as objections to the destruction of a structure widely regarded as one of the most important buildings in the history of British modernism.

A Fall of Ordinariness and Light was commissioned in 2014 by the Foundling Museum for the exhibition Progress as a contemporary response to Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress. It takes its title from Alison and Peter Smithson’s 1970 publication, Ordinariness and Light. The subject matter of the series is typical of Brennan’s work, which often focusses on sites of physical and social change, where inhabitants are affected by circumstances beyond their control.

Visualising the demolition of a building associated with a strong and protective welfare state exposes the contradictions of urban ‘improvement’ and questions the premise that progress is cumulative. These trompe l’oeil renderings point to the paradoxical vulnerability of a concrete structure and critique the casual disposal of the residents’ homes.

Practice and politics come together: the drawings are the product of intense labour, manifested through their detail and finish. What makes something worth this degree of work? If the image of the building is worth this endeavour, what is the value of the ideals that the architecture expressed? What is the value of having a home, and what is the price of losing social housing? Like Hogarth’s cautionary tales, this series of drawings presents a modern moral subject.