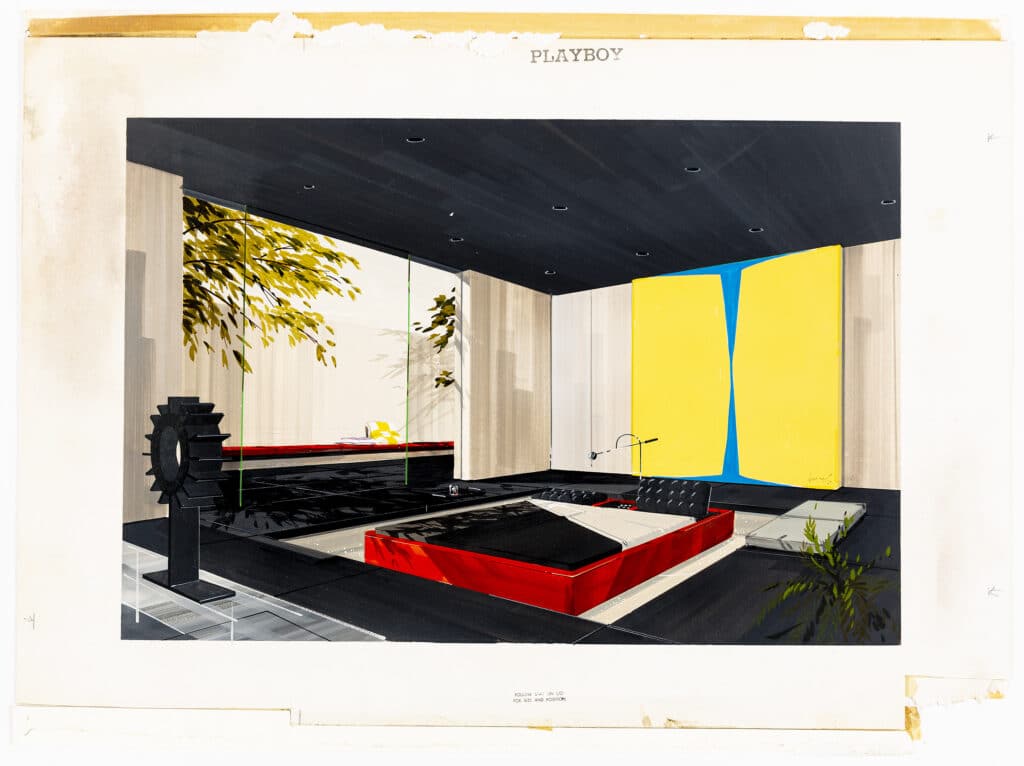

Robert Bray: Design for a Playboy Duplex Penthouse, 1970

Watch Philippa Lewis’s recent lecture, ‘From Drawing to Text’, on how we tell stories from architecture, for The Berlage Center for Advanced Studies in Architecture and Urban Design at Delft University of Technology here.

Geoff Freeman, sales director of a Northamptonshire shoe company, arrives at JFK Airport for his flight back to Heathrow. Tired, and not relishing the prospect of seven hours in the air, he wanders over to the newsstand and spends $1.50 on the January 1970 issue of Playboy. It feels a bit risqué, but he justifies it to himself: 304 pages will see him occupied till he goes to sleep, plus it has a story by Graham Greene, and The Quiet American is one of his favorite books. This is true, but he is also curious to look at the magazine.

Carefully folding the magazine inwards to conceal the alarmingly explicit bodies on its cover, he makes his way to the departure lounge. He only unfolds his purchase when he is on board the Boeing 737, a Scotch in hand. Besides the Greene story, there is something by Tennessee Williams and a ‘candid conversation’ with Raquel Welch that he reads because he enjoyed her playing Lust with Dudley Moore in Bedazzled. He uneasily flips through the rest, pausing only to be baffled by the suggestion in the ‘Modern Living’ page that he should ‘hail the new year’ by holding a Roman Revel in his ‘pad’, where:

a phalanx of fun seekers show up in appropriately wanton moods and costume […] A satyr sporting fur slacks and carrying pipes of Pan would undoubtedly insist that his wood-nymph date wear nought but a see-through gown.

‘Christ, not in Northampton’, he thinks, and makes a mental note to jettison the magazine before he gets home. Rosemary would scream blue murder if she saw it – months and months of ammunition for that women’s lib coven of hers. Geoff Freeman shoves the magazine in his briefcase and goes to sleep.

Many hours later Christopher Freeman rifles through his father’s briefcase in search of free pens from American hotels. Finding Playboy instead, he scurries off with it to his bedroom and telephones his friend Barry to ask him over. Christopher’s father is sleeping off his jetlag in front of the TV. His mother and older sister Mandy are out at a WLM meeting and won’t be back for hours and hours – there’s some conference in the offing they’re very worked up about.

Sitting side by side, the boys pore over pictures of the Roman Revel party, failing to convert any girl they know into a ‘mini-togaed swingstress’, or indeed imagine themselves as ‘horizontal hedonists’ in laurel wreaths. ‘Dream on’, says Barry, who is marginally less of a nerd than Christopher, since he owns purple loon pants and an Air Raid Warden’s overcoat. But the pages where Playboy plans a Duplex Penthouse provide them with an easier fantasy. There are no accompanying shots of pneumatically bosomed girls – the text simply refers to females as ‘fond companions’ or ‘special someones’. What really turns them on, here, are the gadgets: electronic, transistorized, motorized, and automatic. Christopher reads from the page:

A coolly elegant urban haven that combines the intimate privacy of a Roman atrium with architectonic spaciousness.

‘Is that where they got the idea for the Roman orgy party, d’you think? The living room has a reflecting pool – that’s pretty gross, bet it gets full of fag ends – but, listen to this bit!’ Putting on his best attempt at an American accent, Christopher continues:

When the painted panels have been flipped out of the way by remote control, the room becomes the sounding board for the latest in audio technology – four-channel stereo tape.

Four electrostatic speakers are connected to a 600-watt amplifier that puts out 150 watts IHF music power per channel. You can select whatever sound source suits your fancy…

Barry, whose stereo record player from Boots is rarely silent, says he’s not sure about a four-channel stereo, he’ll ask down the record shop. ‘How much money do these guys earn to own all this gear’, he mutters. Christopher continues:

Platters that require very delicate handling are stored by hand in padded bins below the manual turntable.

‘Hey, did I tell you that pig, my sister Mandy, left my Easy Rider album on the radiator and it melted? Mum suggested I turn it into a flowerpot. Man, just imagine not living at home’. Barry tries. He could see many advantages, among them not having to face his mother’s pink flowery wallpaper in the lounge. Chris reads on, his American accent by now becoming rather Irish:

In the center of your sight-and-sound set up are three color TVs with 25-diagonal-inch screens (while you are watching one show, you can be transcribing another on set number two and have the third one free for closed- circuit monitoring).

‘D’you know a single person with even one colour telly?’ Barry howls. ‘I’ve seen them for sale. A Murphy 19 in. costs 285 guineas. Closed-circuit monitoring – in our flat, why on earth would I want to see any more of my family than I do already? Might be good on the front door though. I could split out the back when Gran came round.’

‘My Gran’s loopy. Here, listen to this: the phony can even have films at home.’

Both 8 mm silent and sound movie and 2 x 2 in. slides (all with synchronized audio tape) can be electronically projected onto any of the three TV screens. However, when a 16 mm or 35 mm film is on the evening’s agenda, a 6 x 12 ft. projection screen can be lowered in front of the entertainment wall.

‘I must be a deprived child, my entertainment wall is just Athena posters. Here Barry, here’s a question for you:’

How do you turn on the myriad flush-mounted ceiling lights installed throughout the penthouse? These too can be controlled from your electronic wall, through the use of a unique card system that enables you to instantly illuminate all or specific areas by simply inserting a perforated card into a slot hooked up to a minicomputer.

‘What would you do with a computer in the house for heaven’s sake?’

Barry, a voracious reader of computer magazines, wonders if this Playboy bloke already has the DEC PDP-11, and if there is any mention of the game Spacewar!

‘How d’you know about all this electronic stuff anyhow?’

‘Just do.’

‘Okay, listen. It says:’

All cards are labeled and stored in the wall and, for convenience sake, room lights can be turned on and off by a concealed button.

‘Shuffling through cards sounds a pain, think I’d rather have a switch I could find easily. God, it says here that incoming phone calls first register on the entertainment wall and an answering service takes the message or transfers the call to the area you’re in. Do you think that’s a real person or a machine? Knowing Playboy, it’s probably some blonde bird in a bikini sitting behind a motorized wall.’

‘What’s that great yellow box hanging from the ceiling?’

‘Dunno, something to do with the kitchen. Let’s look at the bedroom.’

‘Hang on, is that the bathroom?’

‘Yup, apparently it’s a ‘multi-mirrored master bath featuring a sunken soak tub set in a radiant heated floor,’ and if you push the mirrored doors you’ve got a wood-lined sauna for two, complete with sun-lamp. D’you suppose it’s sexier if it’s sunken? Clever drawing of the mirrors, though.’

Barry leans closer to the page, ‘Blimey, it says that the bedroom is kinetic. That’s freaky, but how?’

Chris, reverting to his Midlands vowels, reads with a degree of wonder in his voice:

This is 1970 and being turned on electronically by whatever feeds you and your date’s audiovisual fantasies is really the name of today’s bed game. Once the floor-to-ceiling painted panels on the wall behind the head of the bed are flipped back, a battery of projectors connected to the control panel between the headrests can – if you so choose – turn the room into an electric circus of swirling colors that contrast with blinking strobes fired in time to your choice of far-out sounds. Or, if a softly romantic mood is what you’re after, the room can glow like an ember, the walls and ceiling pleasantly pulsating, while you’re serenaded by sounds more soothingly conducive to matters in hand.

‘Jeez. Mandy’s friend’s boyfriend says strobe lighting can give you an epileptic fit; still, better on your bed than in a club. By the way, it says that all the gear in the bedroom can be operated from a prone position.’

Barry and Chris try to imagine themselves in this bedroom, with wavering success. Silenced, they each continue reading for themselves about the patio terrace leading out from the master bedroom:

Out here you can kindle a late-evening fire, sip a nocturnal dram or two and listen to a mobile Italian-designed Brionvega AM/FM hi-fi unit adjacent to the fireplace.

‘God, I’d be happy with just that hi-fi, forget all the other stuff. It only costs a thousand bloody dollars. Almost the price of a house. I don’t suppose there are people who really live like this.’

Chris snorts. ‘Hold it, this page says, “What sort of man reads Playboy?”‘

‘James Bond?’ Barry suggests.

A man who entertains with imagination. A hospitable young host, his guests are always treated with the best. From the delectable buffet to the well-balanced bar, his frequent soirées are always party perfect.

‘Sounds like a bit of a poof to me.’

‘It says here that Playboy is read by one out of every three men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-four who earn $15,000 a year and over. Wonder how much that is in pounds. My dad’s fifty-one, well past it. Can’t think what he’s doing buying this rag. He does drink whisky, though. While I was waiting for you, I counted fifteen advertisements for whisky – give me a Watney’s Party Seven any day.’

Extracted from Stories from Architecture: Behind the Lines at Drawing Matter by Philippa Lewis, published by MIT Press © 2021. Order the book here. Some of the texts were first published as ‘Behind the Lines’.