Sketches from Algiers

In October 1975 I returned to Cambridge to complete my architecture course. I had spent my year out in London with MacCormac and Jamieson, an exciting time as it was early days for this young practice and I was one of their very first assistants. In fact, I nearly didn’t return to finish the course, but it was just as well I did. That summer a Chilean architect and his wife had arrived in Cambridge after fleeing Pinochet’s Chile. Fernando Castillo had been a prominent architect in Santiago as well as rector of the Catholic University and political activist, and had been offered a teaching post in the Cambridge School of Architecture. He agreed to take it on providing he could combine it to fulfil another offer made to him at the same time, by the Algerian government to advise them on housing policy in Algiers. In short, I was amongst the lucky group of students who got to work on this project. How he managed to persuade the government that the advice would in reality be his students’ rather than his own remains a mystery, and I have no idea if our ideas were in any way useful to them or to the inhabitants of Algiers.

The fourth year was traditionally the ‘planning’ year, when students were required to look further than the design of individual buildings and to learn about wider issues such as the urban environment. To do so in the context of what we then called a ‘developing country’ was an exciting challenge indeed. Under the direction of Fernando Castillo, Tim Sturgis and Catherine Cooke, and with termly trips to Algiers paid for by the Algerian government, sixteen or so of us explored a mixed-use and rather downtrodden area of the city (Hamma-Belcourt, where Camus had spent his childhood), devising ways to improve and develop it as a coherent and self-sufficient part of the capital.

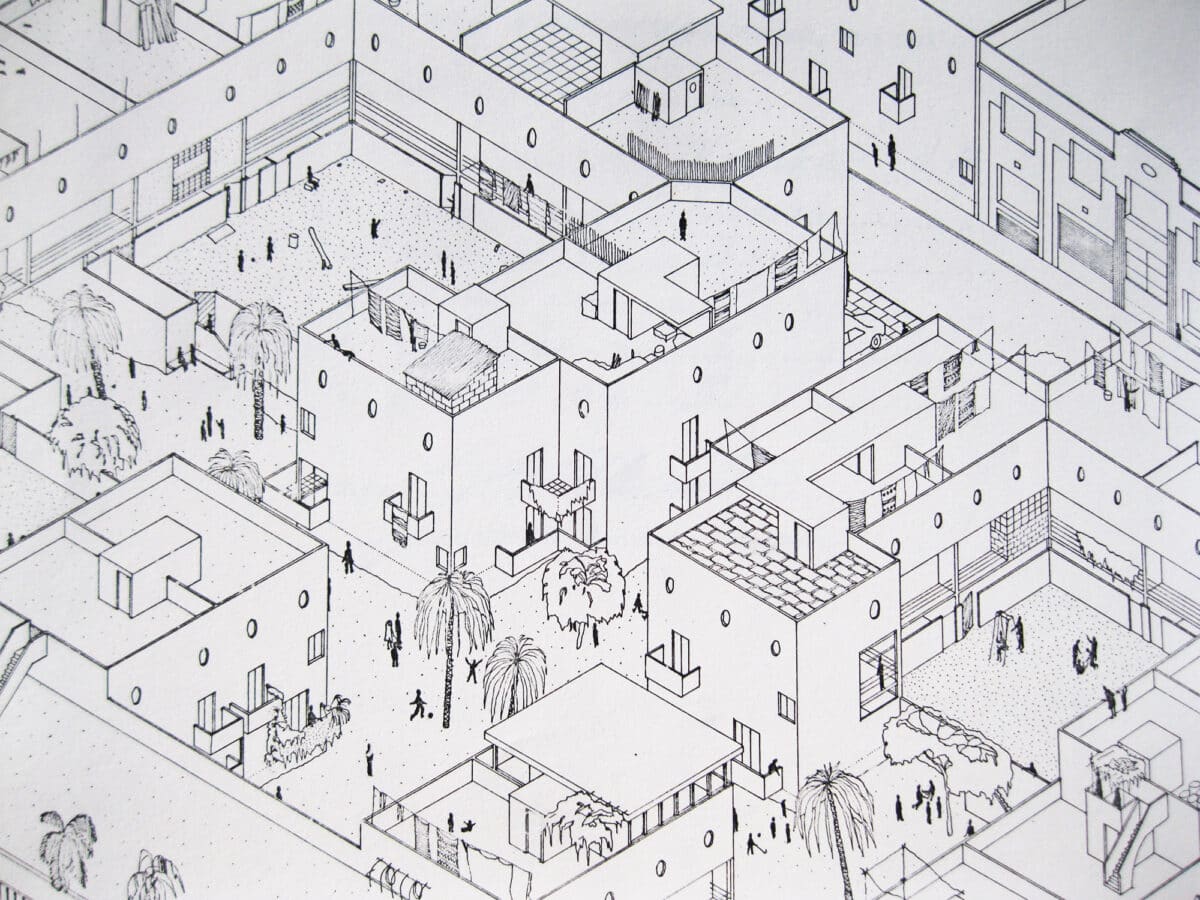

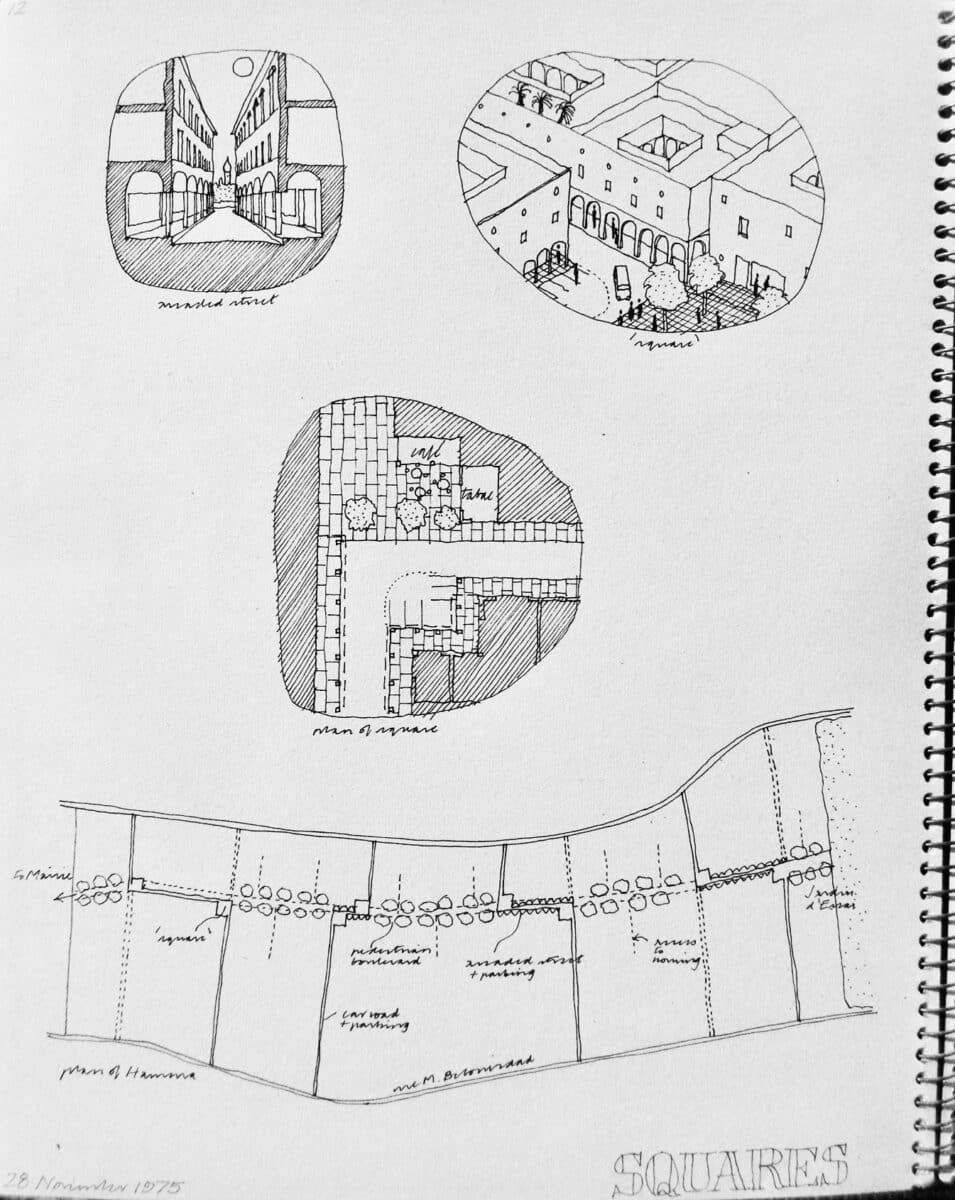

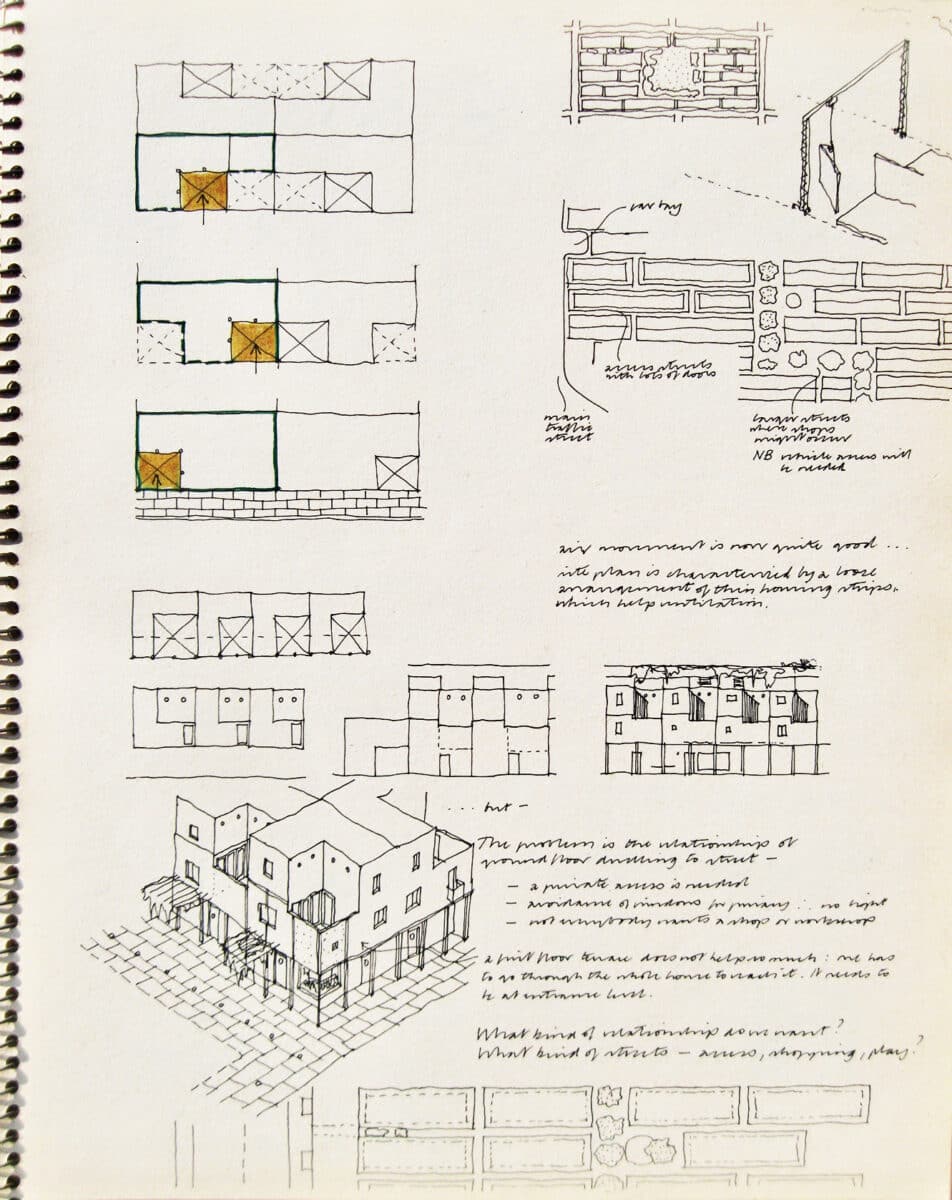

We proposed low-key and incremental interventions, keeping housing to two- and three-storeys rather than the higher blocks being planned; we suggested traffic systems that favoured pedestrians over cars; we tried to show that a rich, dense fabric of mixed use was preferable to the sterility associated with zoning. Once we had formulated a general planning strategy for the area under question, each of us went off and designed a building. One student chose an office block, another a school. One more adventurous student ventured to design a mosque for the district. I chose housing.

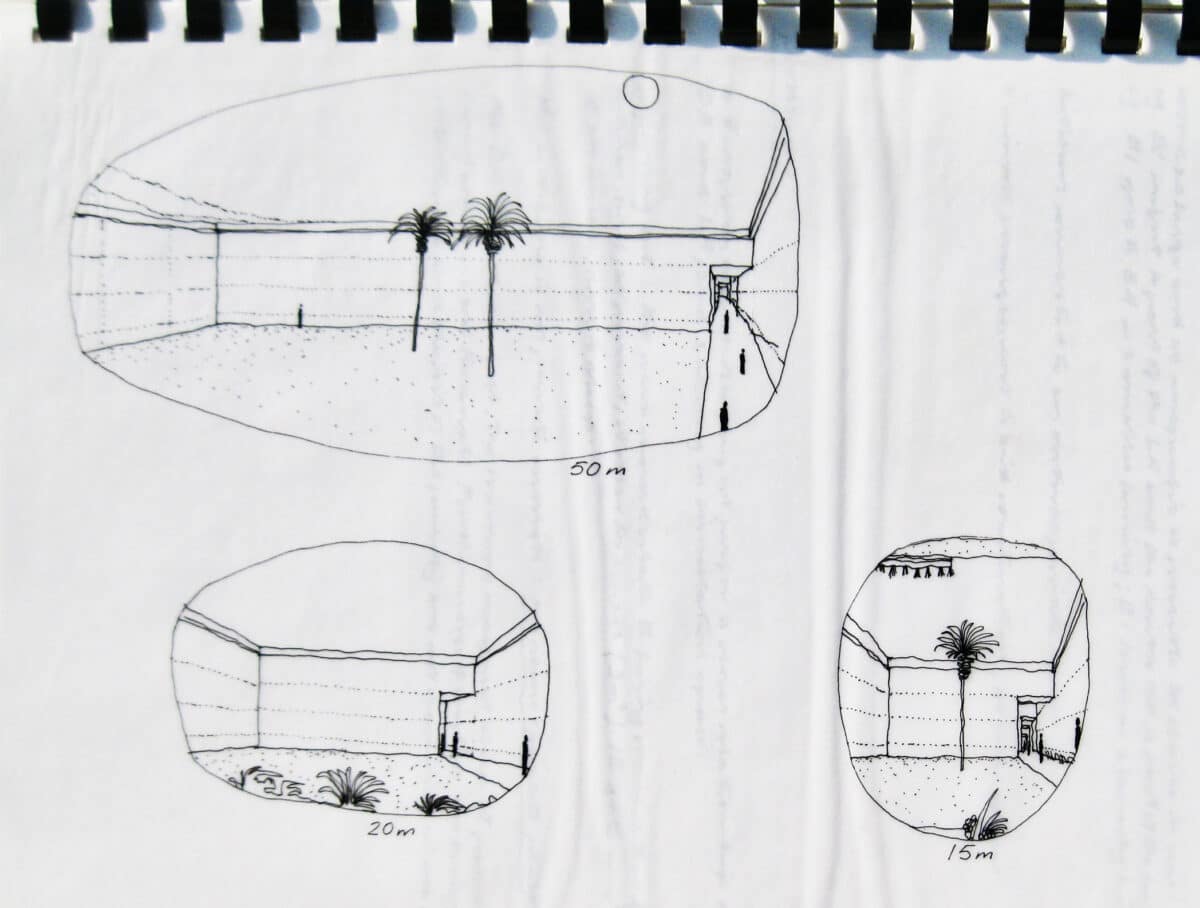

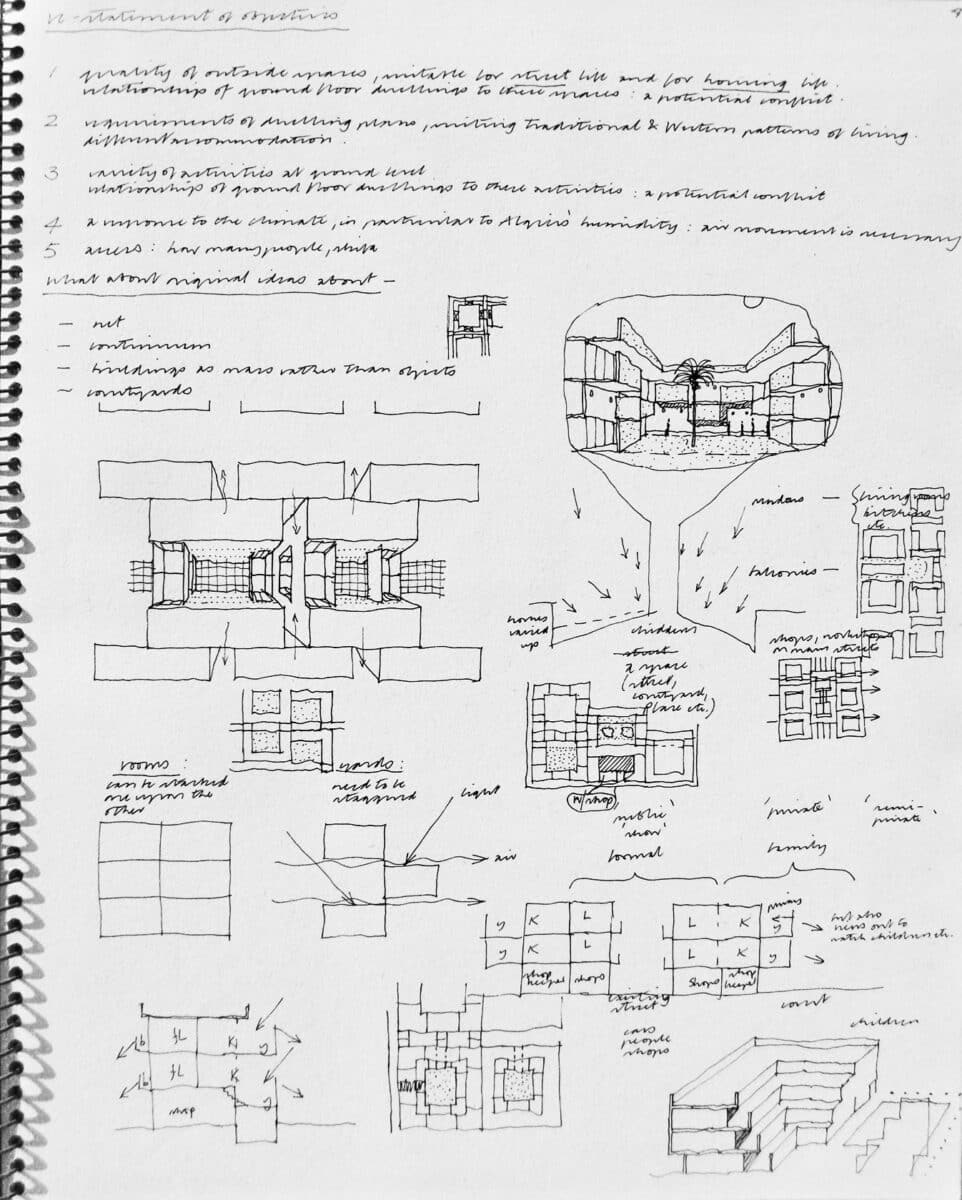

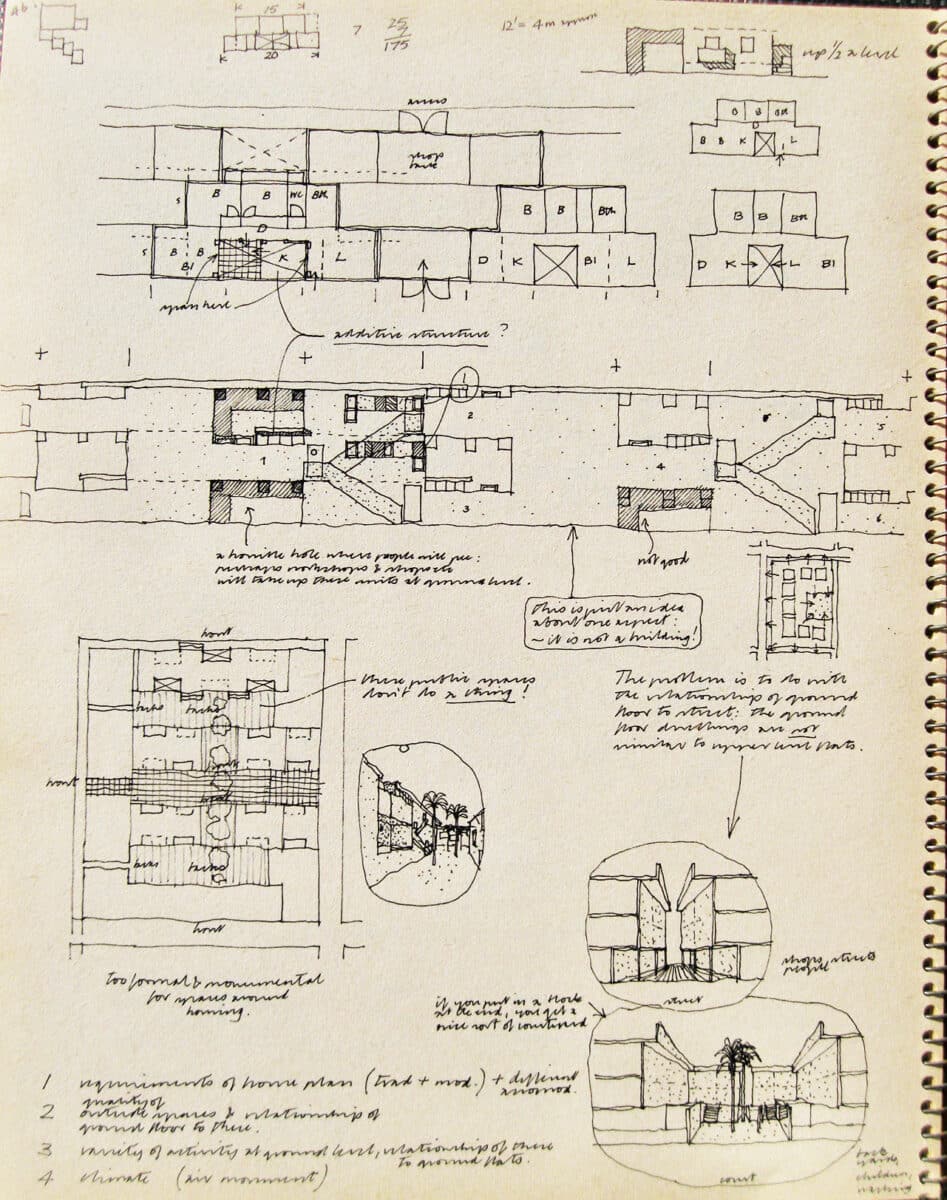

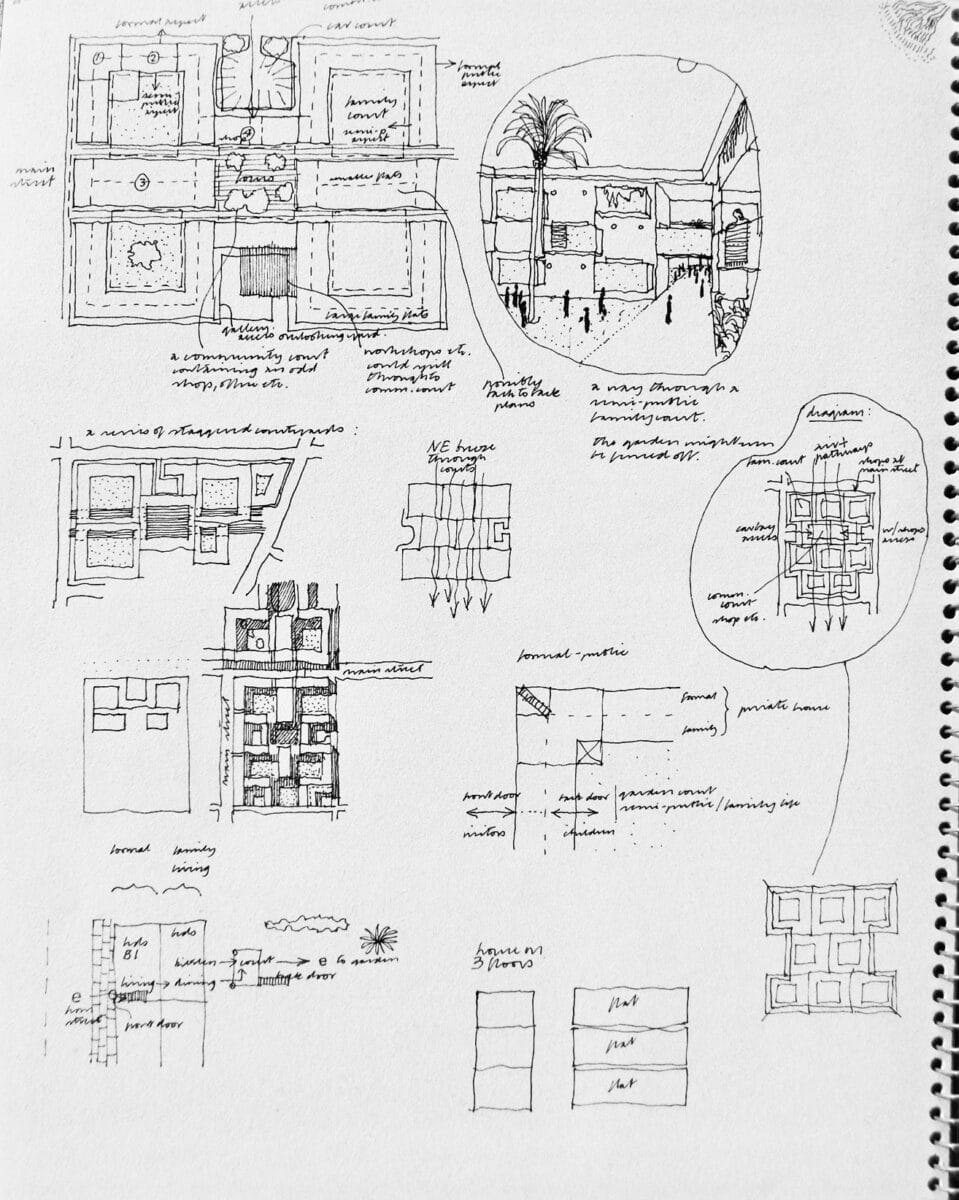

Much of my work is recorded in a ‘Cantab spiral notebook’ I kept at the time. Squarer than A4 in size, this sketchbook amazes me now with its detailed sketches, diagrams and notes, most of them done with a 0.2 Rotring pen and often so miniscule that they are hard to decipher with eyes no longer young and sharp. What I earnestly wrote in words embarrasses me now in a way that my sketches do not, yet I can’t help thinking my sketches show a rush to foregone conclusions without the proper investigative groundwork.

I see too many shades of Le Corbusier, of some of the early North African housing projects by Candilis Josic and Woods, and of other Team X projects – all relevant maybe but I was jumping to conclusions made by others rather than following my (and my colleagues’) investigations. Yet, I do remember the Casbah being a major inspiration to us all, at least those of us involved with housing. I was determined to use this old part of the city as a model, not just for its dense, low-rise urban form but for its basic element, the courtyard house on three or more floors.

My mission, I recall, was to create in Hamma a casbah, an improved casbah relevant to a twentieth-century westernised Muslim society. My sketches abound with references to Islamic domestic architecture, chiefly shady courtyards with colonnades and pools of water etc etc. Including lush vegetation and palm trees in my sections and elevations helped a lot, of course, and sharp, dark shadows added the right atmosphere. Where the house plans began to resemble those of housing schemes I admired in London (for instance, those designed in Camden under Neave Brown, even Bill Howell’s terrace in South Hill Park, where I had lived during my year out), I persuaded myself that this was the good side of Western civilisation influencing the more traditional, Muslim patterns. Some circular windows even appeared at one point because, I’m afraid to confess, I knew Robin Nicholson was going to give us a crit and I liked Stirling’s Runcorn housing (heaven knows why). These out-of-place features didn’t survive in my final scheme, I’m pleased to say, and I returned to more traditional rectangular windows with French-style shutters, painted blue.

I had visited some of Fernand Pouillon’s housing schemes in Algiers and had been impressed by them enough to copy some of his features. I even went with a student friend to meet him in his office but cannot imagine now what he must have thought of us and our naive questions.

At the end of the year, Fernando asked me if I would give him my sketchbook. Much as this touched me, I could not bear letting it go. I felt mean for years, and still do, but at least I still have it, almost half a century later, a record of how students used to work in the pre-digital days of paper and Rotring.

– Eric Parry