The Lovell Health House: Richard Neutra’s Revolution in Building

‘Paris, 1927. I was in Lurçat’s studio on the rue Bonaparte looking for the first time at reproductions of the ‘Health House’ of Neutra. We young followers of the new architecture were both admiring and astounded by this signal of a revolution in building.’

Willy Boesiger, introducing Richard Neutra. Buildings and Projects (Zurich: Girsberger, 1951).

Beginnings

Richard Neutra was raised in Vienna, where his father owned a small steel foundry that produced machine tools and parts. In 1911, he entered the four-year architectural programme under Carl König at the Technische Hochschule, working for part of his second year in the independent studio of Adolf Loos, whom he assisted in site inspections for two pioneering residential projects, for Steiner and Scheu. He interrupted his schooling in July 1914 to enter military service, serving for two years in occupied Serbia before his health collapsed, which brought him back to Vienna. There, too weak to return to active duty, he was able to complete his schooling, receiving his professional degree in July 1918. After two years of occasional practice and advanced study—while convalescent in Slovakia, Zurich, and Vienna, notably with landscape designer Gustav Amman and the progressive ETH professor Karl Moser—he moved to Berlin in October 1920; by then, his health was largely restored. During three productive years in Germany, he qualified for practice, became a member of the Werkbund, built an exurban cemetery and housing colony during a short term as city architect of Luckenwalde, and eventually joined Erich Mendelsohn in the autumn of 1921. There he worked for two years, in design of the landscape plan for the Einstein Tower and as project associate on three seminal advances in modern building: the ‘Mossehaus’ for Berliner Tageblatt; a group of concrete suburban single dwellings in Zehlendorf; and an unbuilt commercial centre for Haifa, in which the new Zehlendorf language of plain bands of low-slung concrete and ribbon windows would have been deployed at an urban scale.

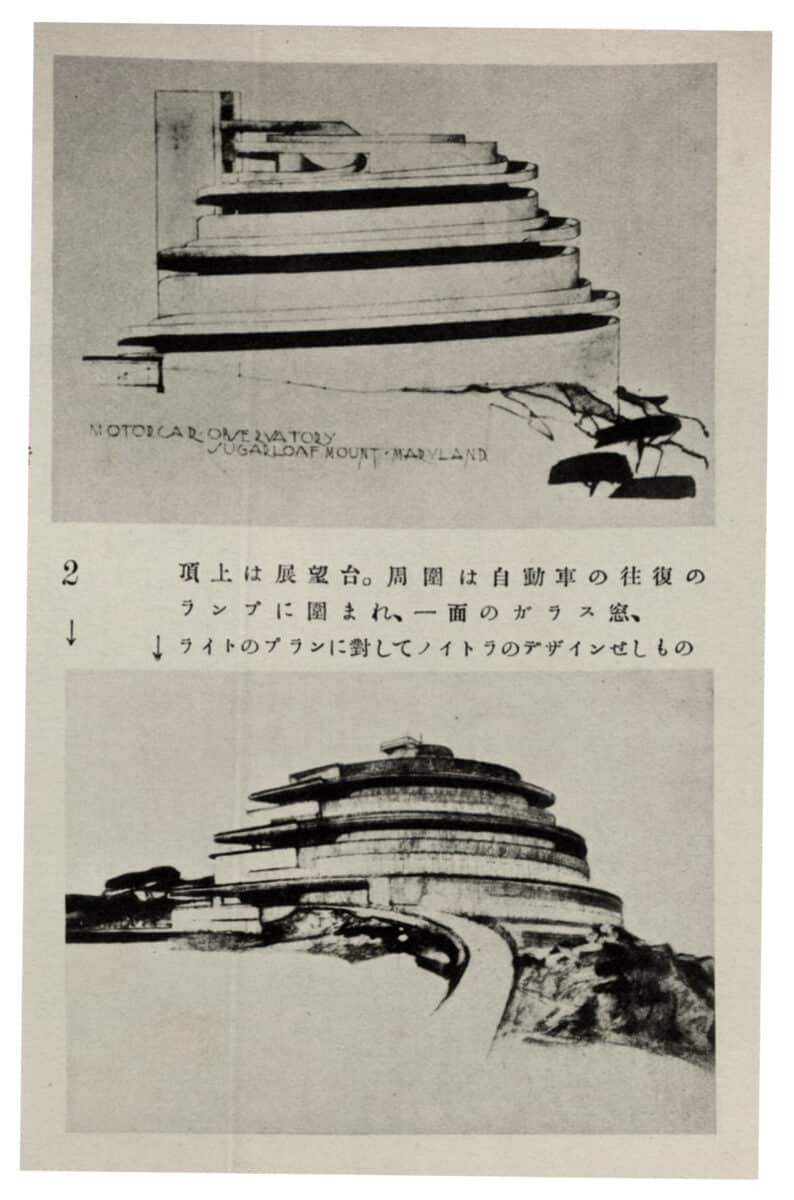

Looking to learn advanced industrial building systems and report on them to European practitioners, Neutra left Berlin for New York in October 1923 and worked there briefly before moving to Chicago for a job as draughtsman with Holabird and Roche, with his own experience on the steel-frame Palmer House hotel being exceptionally instructive. He had long been an admiring follower of Frank Lloyd Wright, and did not hesitate when, in summer 1924, Wright, then isolated at Taliesin and virtually devoid of new work, offered the chance to move in and work with him, alongside Karl Moser’s son Werner and the Tokyo architects Kameki and Nobu Tschuhuria. Wright assigned to him the remarkable spiral Automobile Objective for Gordon Strong, which Neutra developed with great independence, basing it on Wright’s slight conceptual sketch, and blending the two sensibilities—linear and plastic—of Wright and Mendelsohn (whom he introduced to Wright at Taliesin) into a fully developed set of studies, working drawings and perspectives—a number of which he retained and published in his own name. At the same time, he played a critical role in bringing Wright’s new work to a new generation of German editors.

Neutra left Wisconsin to follow the Tschuhurias to Los Angeles in February 1925. There, he joined Rudolph Schindler, an architect whom he had known briefly in Vienna as one of the circles of Adolf Loos, and who had settled in Los Angeles, initially as project manager to Frank Lloyd Wright. Neutra and his wife and son took the secondary apartment in Schindler’s remarkable house of slab concrete on King’s Road. He worked by day as a technical draughtsman for a commercial firm downtown and by night on two extensive theoretical studies.

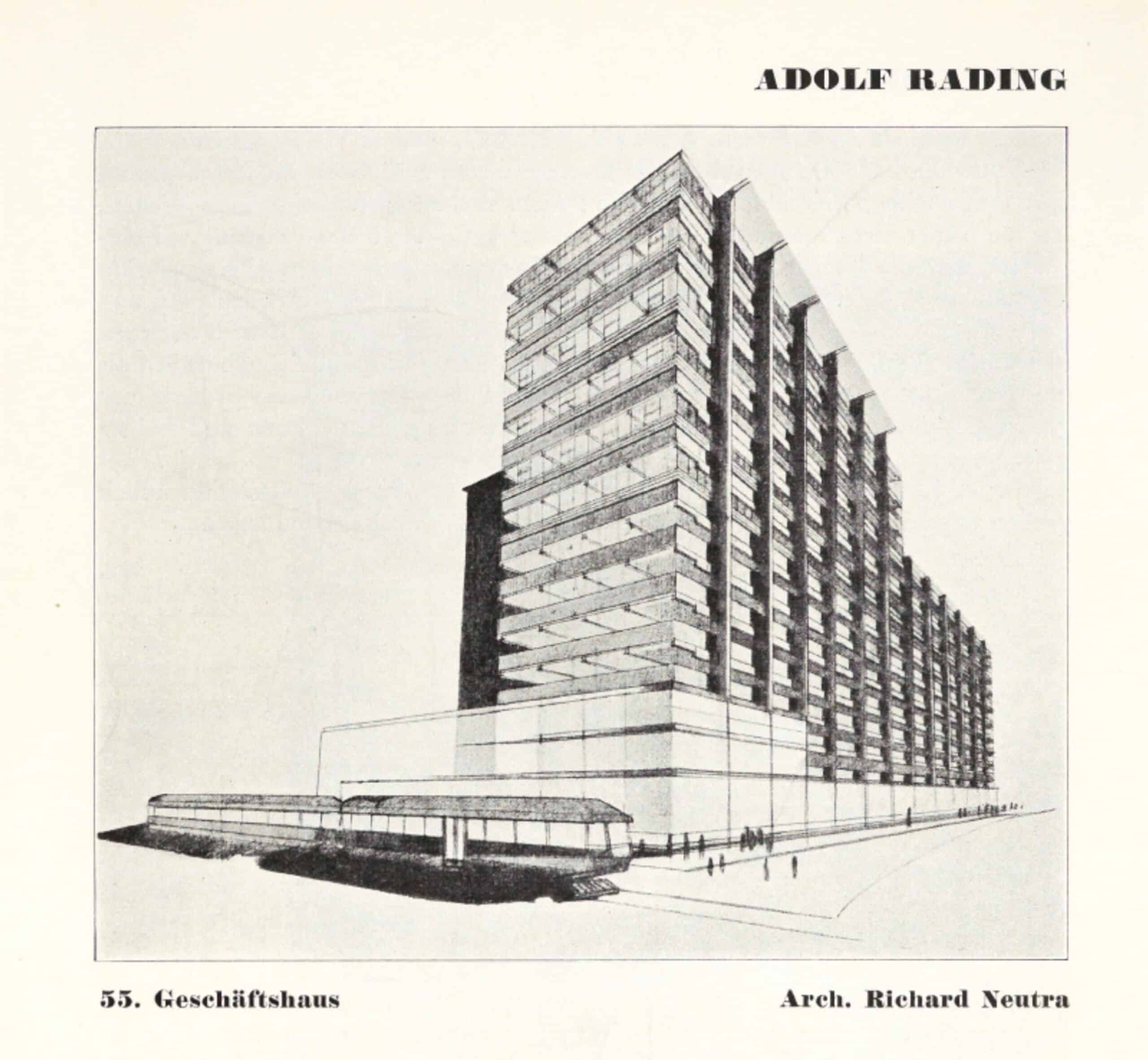

One was an evolving model for the architectural equipment of a motorized metropolis, Rush City Reformed, elements of which were widely published in German-language journals over the next seven years, starting with a ‘commercial building’ dating from his time in Berlin, fully rendered in 1925, and then published by Gropius in his widely circulated 1927 edition of the Bauhausbuch on International Architecture, identifying its author as an Austrian architect. It was then picked up by the European press in 1928 as an icon of the functionalist future—Neutra now defined as American—reaching France, Russia, Denmark and Italy when it took the cover of a special issue on modern architecture for Karel Teige’s ReD in Prague, and was accorded an emblematic place by Fritz Rading in Fritz Block’s seminal book on advances in construction, to which Neutra himself contributed a major technical essay on steel structure.

That essay grew out of his second major project, also conceived in Berlin, which was to introduce the progressive European architectural community to the new industrial scale of American building practice. This he did both through columns in monthly journals, notably Die Form, Das Werk, Baugilde and Das Neue Frankfurt, and in two major photographically illustrated books, the first on construction, which appeared in 1927 as Wie Baut Amerika? and the second, in 1930, exploring the general development of a new spatial and formal language (or ‘Stilbildung’) of architecture in America, as part of a series on Neues Bauen in der Welt,commissioned by the great Vienna art publisher Anton Schroll and designed with El Lissitsky.

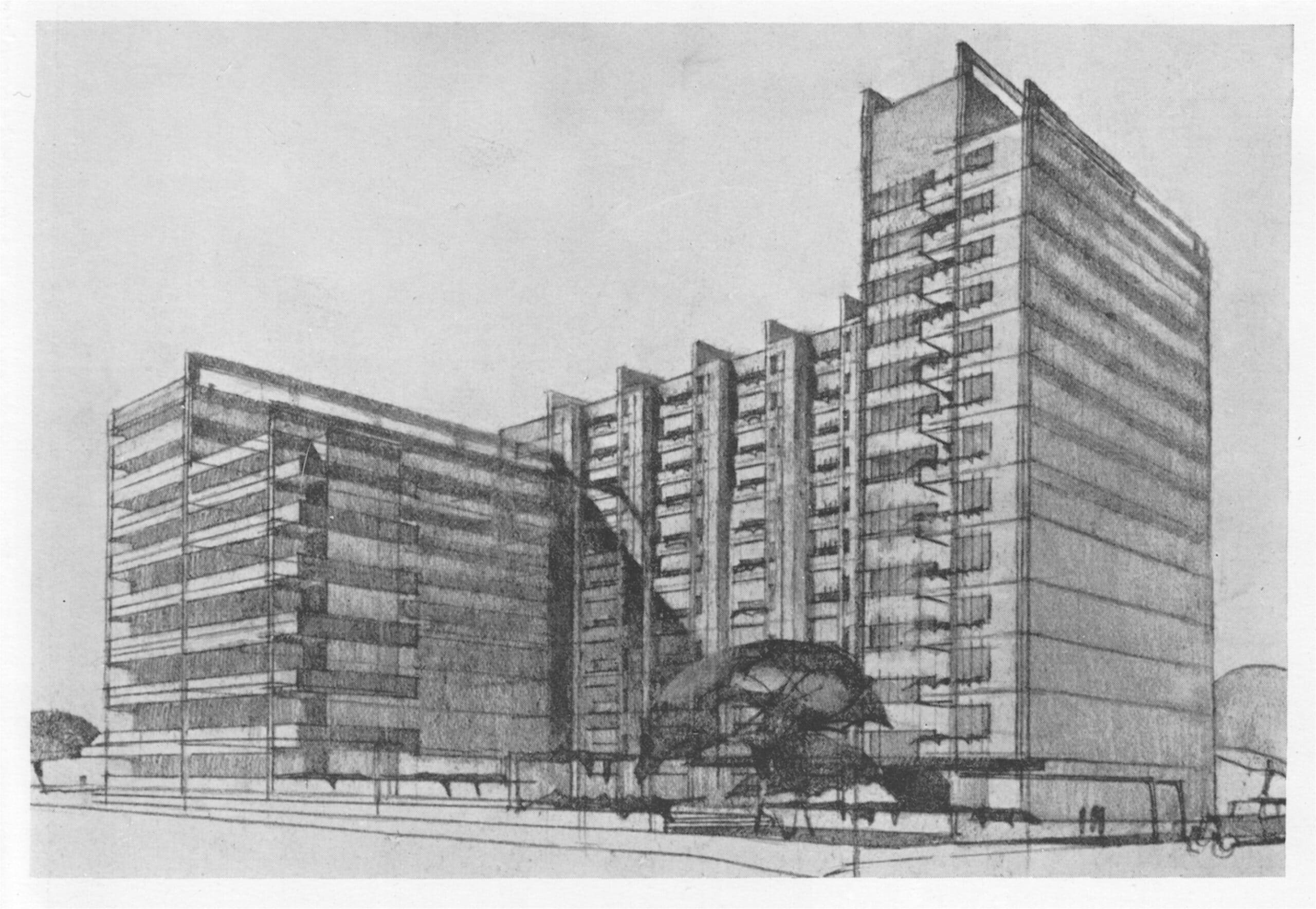

Early in their time together, Neutra and Schindler established a working association to solicit and design public works, a short-lived partnership for which only one significant joint project—their widely acclaimed submission for the League of Nations Palace in 1926—was forthcoming. When a second major project appeared in 1926-27—three large ‘garden apartment’ buildings in Hollywood for a developer working in the rental market for economical, minimal units to serve working professionals in the film and allied industries—Schindler was so deeply engaged in the work involved with his great summer house and teaching studio on Catalina Island for the costume designer Ethel Wolfe that the work fell almost entirely on Neutra’s shoulders, and the projects soon became his own. With them—the first significant works under his own name—he attempted to introduce himself to the world as an American modernist architect and—somewhat to Schindler’s discomfort—did so with remarkable success.

The smallest of the three complexes—43 units in three wings of glass and concrete known as the ‘Jardinette’—was designed and built at pace. Though a second, larger project moved into an advanced stage of design, the developer absconded shortly after ground for it was broken. ‘Jardinette’ itself was completed late in 1927, just as Neutra began work on the Health House, which drew heavily upon its constructive systems. A rich set of photographs by Willard Morgan encouraged an extraordinary reception for Jardinette, from the daily press in the United States and popular art publications in Britain, who acclaimed it as a hygienic, healthy prototype for the modern city, stripped of the historical and decorative references of a typical masonry American tall building; while architectural writers throughout Europe and Russia—introduced to the principles of the three schemes by Neutra himself in a long illustrated essay, with plans and elevations, in Das Neue Frankfurt in April 1928—saw its formal and material innovations as a revelatory expression of Functionalist planning, construction and housing principles.

Sigfried Giedion heralded its interrelationship of indoor to outdoor as a pioneering example of his ‘Befreites Wohnen.’ Walter and Ise Gropius were so fascinated by its continuous line of windows that they travelled to Los Angeles to see and photograph it. L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui placed it alongside villas of Mies and Loos as icons of l’esprit nouveau on a poster to announce their first issue. And it persuaded the organisers of CIAM (who knew him well) to invite Neutra to serve as their first US representative and to introduce his ideas—alongside Gropius and Le Corbusier—to the central debate at the Brussels meeting of 1930 on patterns of urban dwelling. By that time, Neutra’s perspective drawing for the largest and least developed of the three complexes—four staggered volumes bathed in light and furnished with garden balconies, set back to surround a large landscaped common entry court—had gained extraordinary currency of its own, recycled as his model ‘Apartment House in Rush City’. In that guise, it appeared both in the real estate sections of the American popular press and in the international professional discourse, becoming widely, if briefly, known as a reference prototype for new urban dwelling.

Thus, though Schindler was five years older, Neutra had arrived in California with a wider body of professional experience, quickly established extraordinary international visibility, and worked through the Twenties within a dense European network of architects and editors in the artistic avant-garde. He brought intense discipline and rigour to the working process, where Schindler’s brilliance lay in something closer to improvisation; and the inherently bourgeois and rather dour Neutras tended toward a quiet and sober life while the charming and playfully Bohemian Schindlers filled the nights with companionable society. It was hardly surprising that by the time Neutra left for Japan and Europe in 1930—uncertain of his future—their friendship had essentially collapsed. Although Schindler consulted on some aspects of construction—by the time Neutra took up the design of the great Lovell Health House in 1927 the project was entirely his own, and his extraordinary skill and success in disseminating interest in it—starting well in advance of it taking shape on the ground—built upon an already prominent European reputation for writing about and presenting imaginative advances towards the neue gestaltung—a new spirit of design.

Studies of the Demonstration Health House, 1927

The Demonstration Health House was one of four projects commissioned from the two Austrians by the naturopathic practitioner and health advocate Philip Lovell, whose weekly columns on ‘Care of the Body’ in the Los Angeles Times had built up an extraordinarily profitable clinical practice. Schindler was entrusted with a weekend house in the mountains, whose roof infamously failed, and the justly famous seaside house at Newport Beach, completed in 1927. Neutra was given the design of Lovell’s clinic in Los Angeles, and, in an agreement signed in summer 1927, the family’s principal dwelling, or ‘city house.’ This was to serve as a place of daily living for the Lovells and their two young boys; for hospitality; for the schooling of young children on the principles of open-air learning, play, and performance practised by his wife Leah Press; and as a demonstration of domestic hygiene and well-being, particularly in relation to fresh air, natural light, physical exercise, and ready recreational access to water and the out-of-doors.

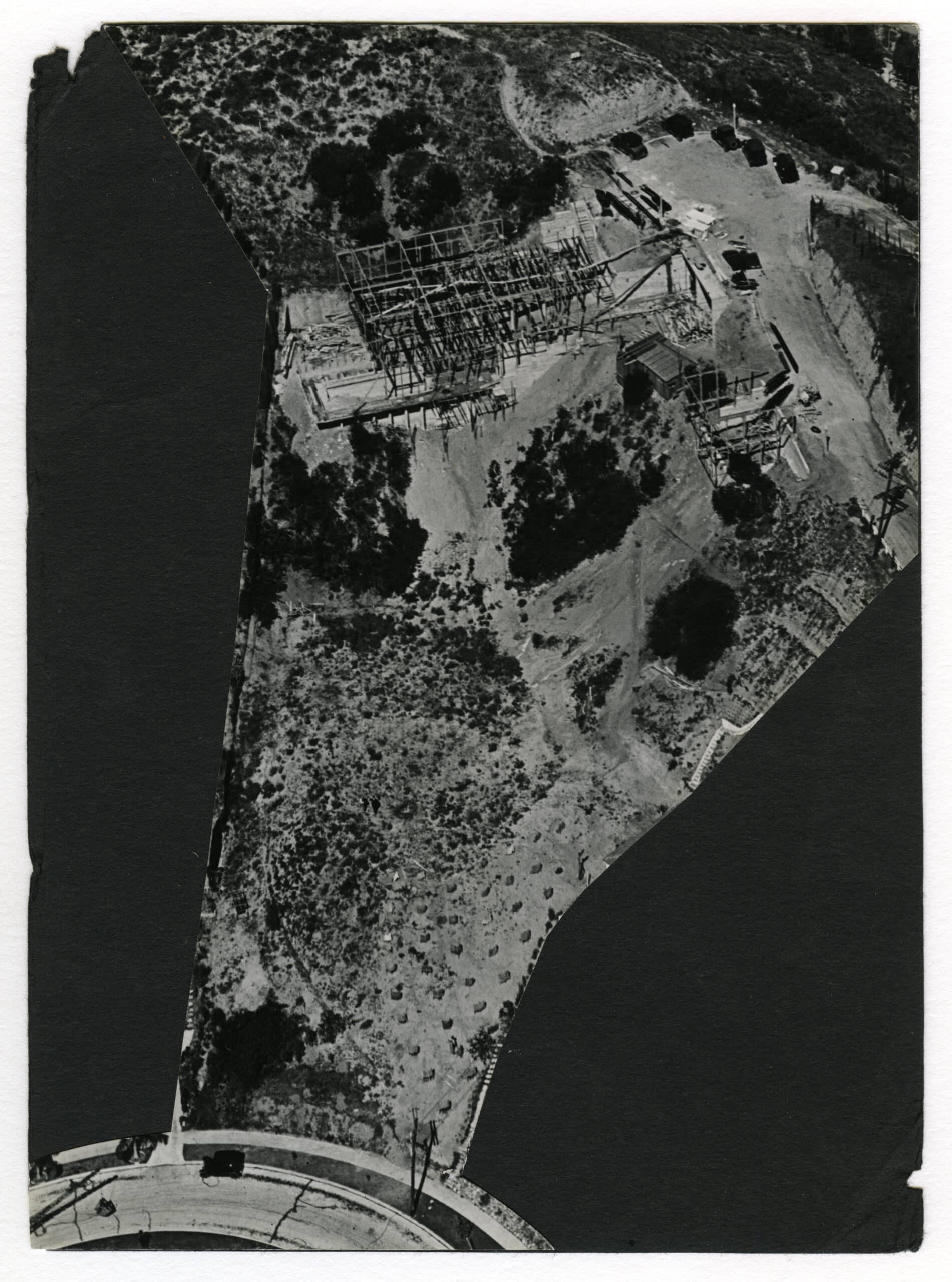

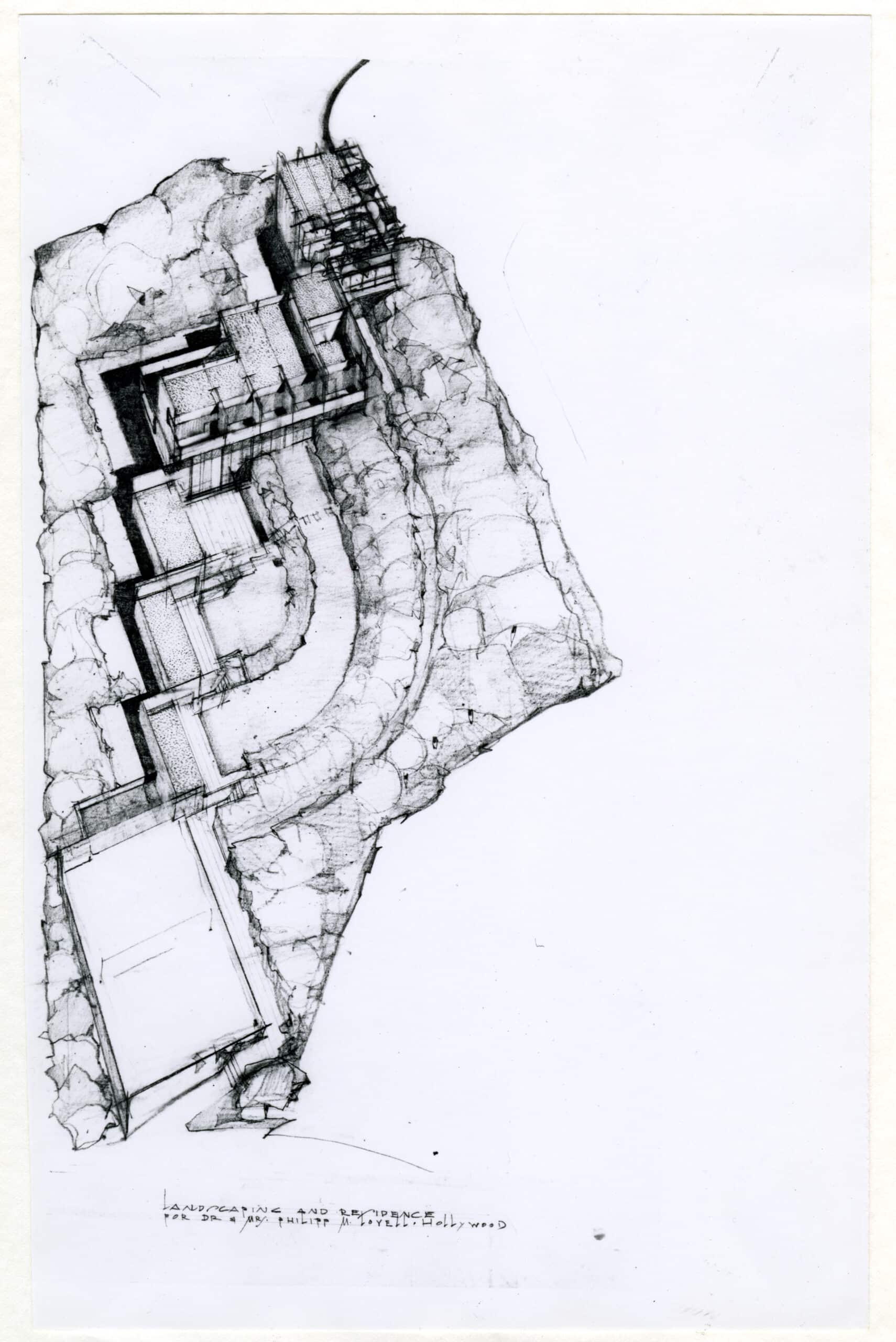

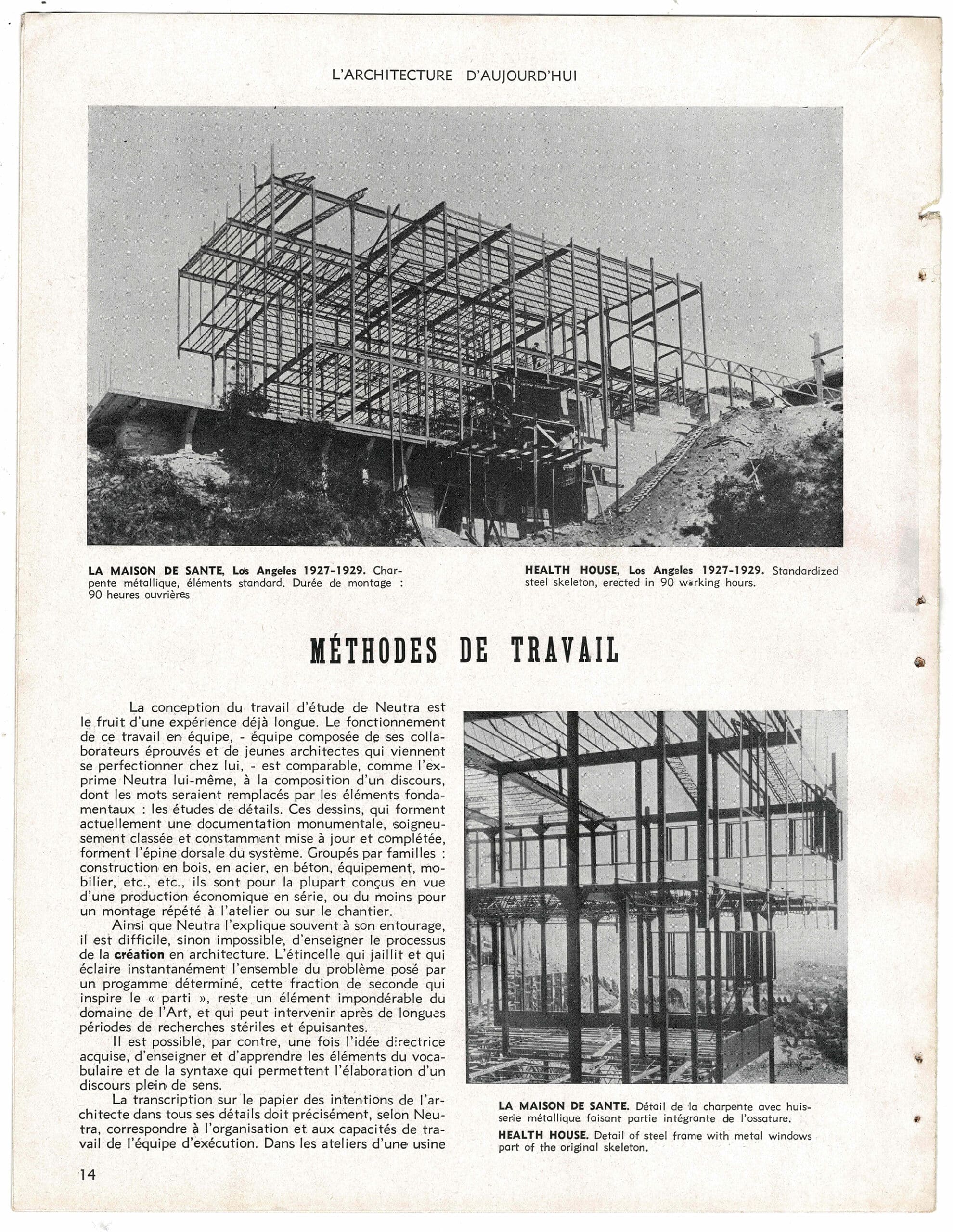

The site—a steeply sloping triangle of chaparral—was on the far boundary of canyons and steep hillside rapidly developing into housing tracts on the northern fringe of Hollywood. It fell at the end of a cul-de-sac, bordered the public wilderness of Griffith Park to the north, and straddled a profoundly unsettled and poorly drained cleft in soft ground. Photostats of a lost aerial perspective show a first concept from 1927 in which two adjoining volumes rest, though lightly, on the upper corner of the site. The lower mass, apparently a single terraced floor rising on posts above a covered court, already begins to suggest the eventual design, in which the structure is organised as a platform across the gully. External recreational and social space falls away within a landscape of curving paths and boundaries, which will persist with ever-increasing subtlety as the plan develops. A construction photograph from the air shows the plot as the prefabricated ‘slender skeleton’ of the final building rises, at extraordinary speed, in summer 1929.

As Neutra tells us, this efficiency in building was the conclusion of a long and patient process of trial, error and testing: ‘Plans were prepared and experimental studies carried on during a period of two years until the most reasonable and economical solution of the problems in hand was decided upon. Detrimental haste was avoided thanks to the owners’ patience for the systematics of such an experiment.’[1]

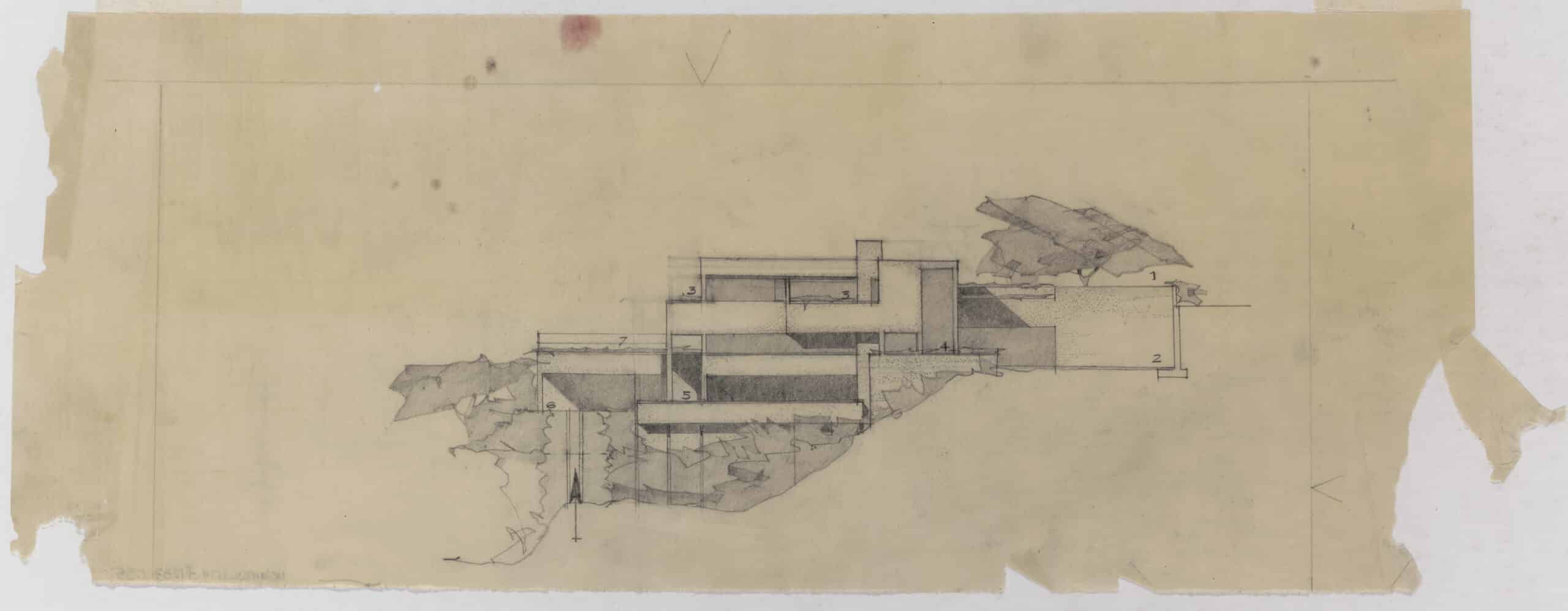

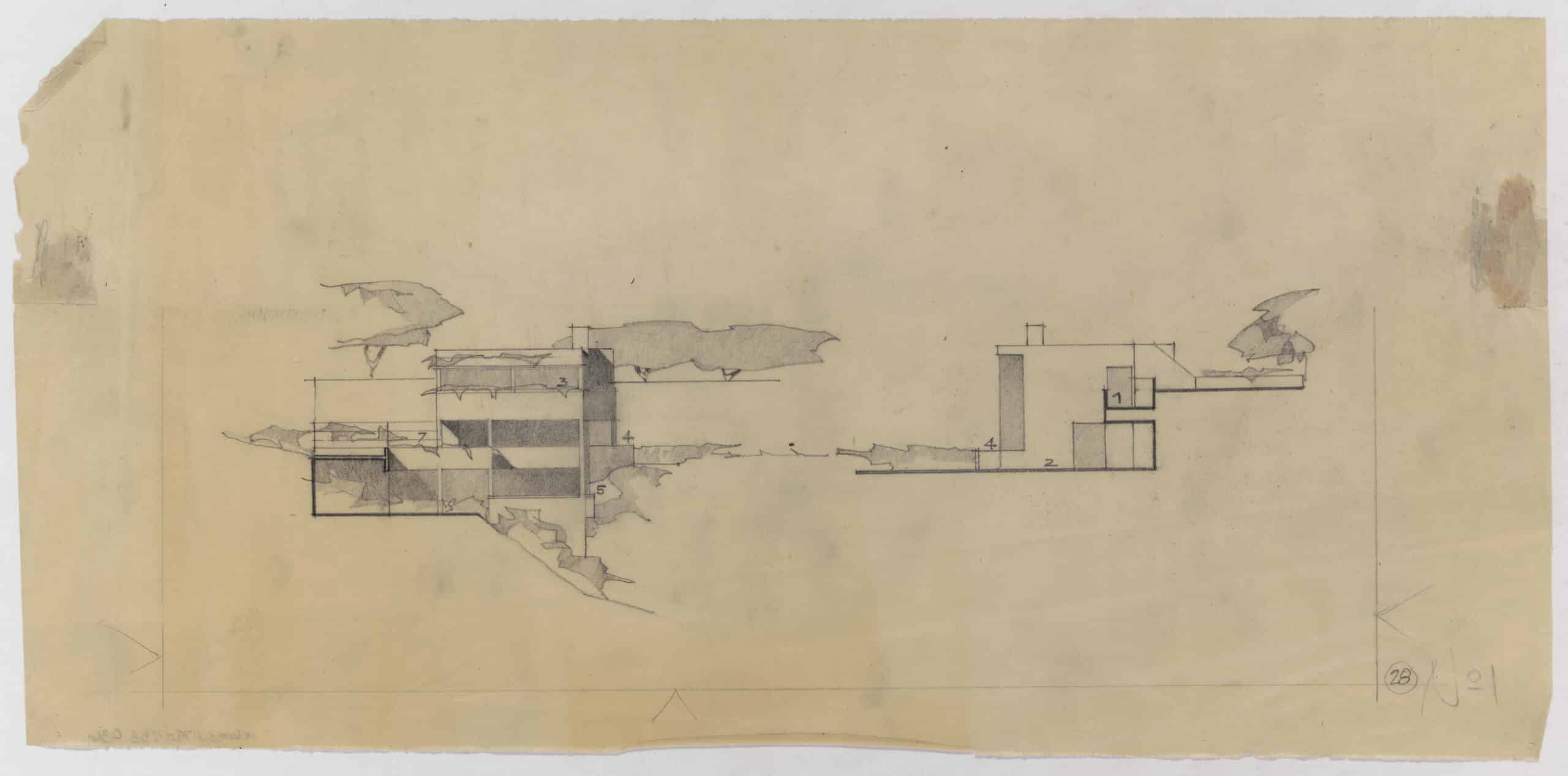

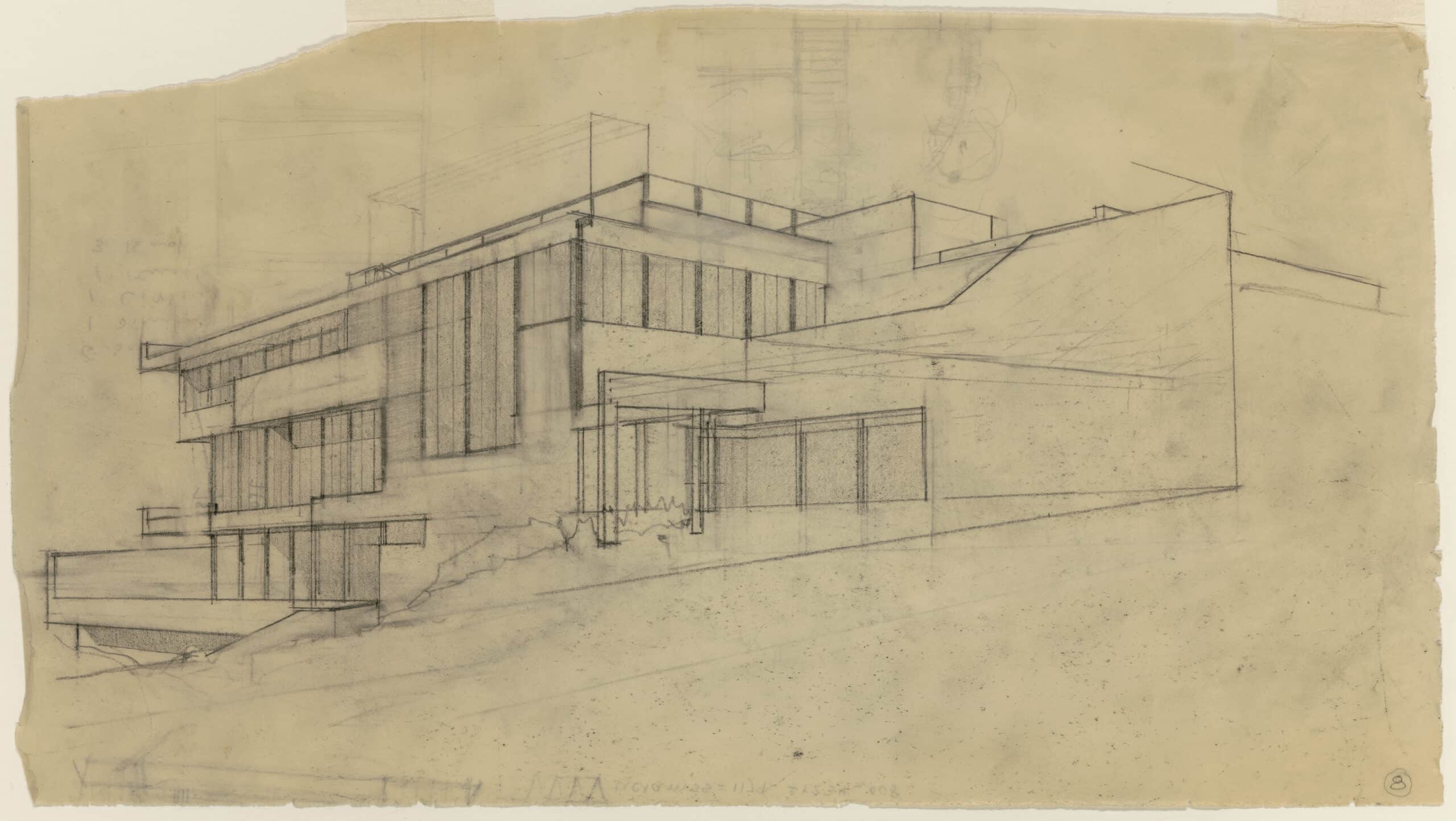

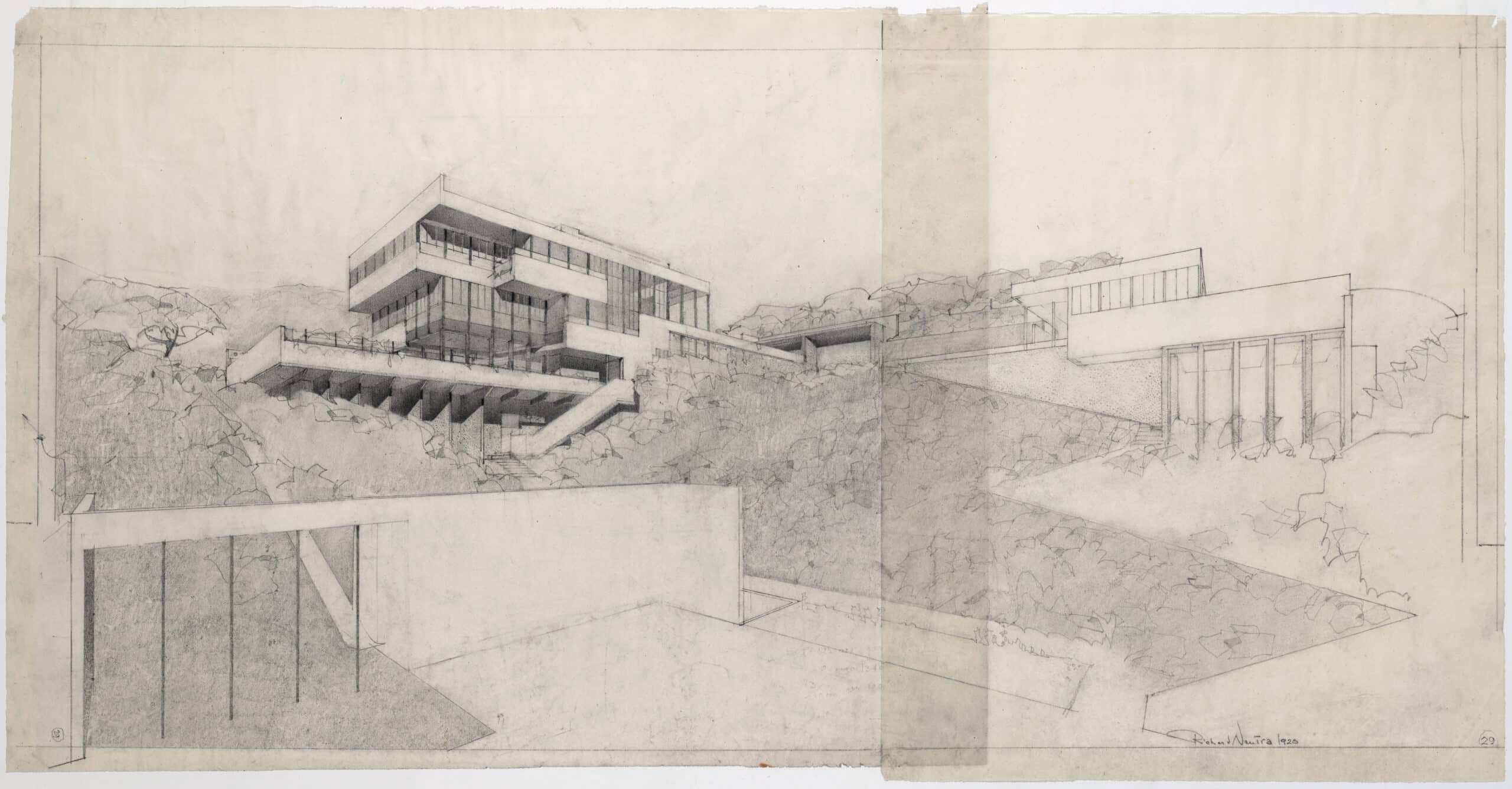

In two sheets for a second concept, the volumes float above the ground on what seem to be steel stilts or pilotis. These are presentation drawings intended for display and circulation, in which the fall of light and shade is clearly rendered, and a key to notes on the use and fabrication was to be provided. Marked for publication, they are probably the source drawings for the ‘first pictures’ famously circulated among the neighbouring studios of the architect André Lurçat and editor Christian Zervos of Cahiers d’Art in Paris by Neutra’s brother-in-law, writer and fellow architect Roger Ginsburger. It is these revolutionary images, appearing late in 1927 and confirming rumours that a ‘floating house’ of glass was to be made by Neutra in California, that at one stroke—in the words of the Swiss architect Willy Boesiger—‘burst open the portals of a new era in architecture.’[2]

With the broad lines of a definitive design emerging, Neutra decided to present the scheme in plan and full perspective, with a short introduction, in one of his columns as American correspondent for Das Neue Frankfurt—at that point the leading international advocate for ‘The New Design’—calling the project ‘a contemporary building work for human physical development’. By the time the magazine appeared in May 1928, this scheme, recording the state of design at the end of the previous year, had been significantly modified, and working drawings for much of the finished design were already detailed. But the essential developments from the second scheme, resting the core of the complex on a cantilevered concrete base rather than steel stilts and granting a distant separate wing for garage and kindergarten, are now evident.

At this stage, the design—seen most clearly on the original colour-shaded drawing which the magazine reproduced—showed an expansive approach to the footprint of the building, with a long line of terrace beneath the road at the top of the eastern slope, and a separate swimming pavilion leading off the house to the west. The perimeters of this design would be cut back to meet requirements from city planning officers, the pool would move to a lower terrace below the house, and the main volume would gradually be brought somewhat further down the slope.

Refining the Design, January – April 1928

Among the experimental ‘systematics’ to which Neutra referred was an intensive period of study and exchange for which a remarkable little archive of sketchwork and ‘discussion drawings’ survives. It seems to date from an intense period of revision between the time of the rendering for Das Neue Frankfurt late in 1927 and the sign-off for contract drawings on 8 April 1928. Different layering and articulation were explored with the Lovells as they suggest new modes of use for the spaces and connections. They may only hint at the extent of studies undertaken to reach a definitive design, and they may not form a fixed sequence, but we can see the design adjusting to Leah and Philip Lovell’s fluid and unusual thinking on recreational space, sleeping conditions and the use of external ‘rooms’.

An early development study shows the programme now compressed within the container and the entire house sited so that the central living floor is close to street level. A later sketch breaks the house free of the box, thrusting out a projection on the lower floor for the pool, setting back an open terrace (soon christened the ‘flower court’) off the living floor, and lowering the house on the site, but adding an open roof pergola so that he same general skyline remains as a form that that spoke to verticality in the first sketch starts to be marked by its horizontals in the second. The principal access—at this point, a winding stair seems to be suggested—is still unresolved.

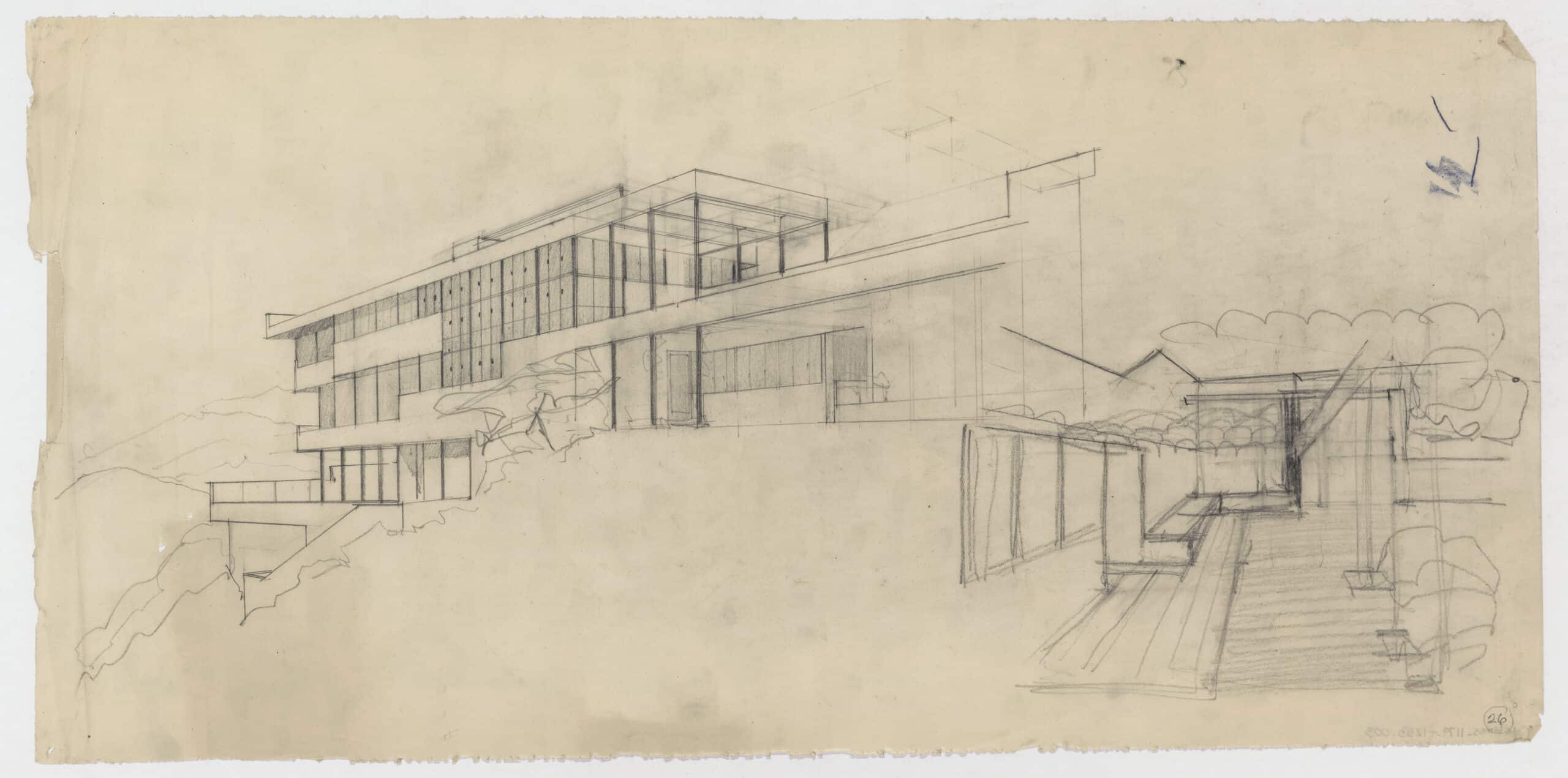

This sketch begins to study the fundamental late ideas in which an approach path in the form of a roof terrace travels like a bridge into the upper floor from a short flight of steps dropping from the roadway, with a free-standing concrete beam and open pergola in front of it to shield and signal the approach and to further anchor the structure. There is now a sense, both felt and seen, of a continuous horizontal through-line, stepping down, into and above the void. The idea of the ‘flower court’ bordering the enclosed library section of the social space is more fully developed, and a rough sketch at a different scale is added to show the rear terrace for the guest and housekeeper’s rooms on the north side. A length of low concrete banding still serves to mark the dado of the living room at its southwest corner.

In a late study for the north and west faces of the building, that band disappears to leave continuous panels of curtain wall at the culminating southwest corner of the social space, providing a sheer boundary where the natural prospect is most dramatic, and recalibrating once again the play of mass and line to restore a powerful episode of the vertical. In this near-final configuration, the swimming pool carries the gymnasium floor out on a terrace to the west above a row of concrete elbow braces, with a protective wall to the north to baffle the canyon’s evening wind.

Unfolding the Space

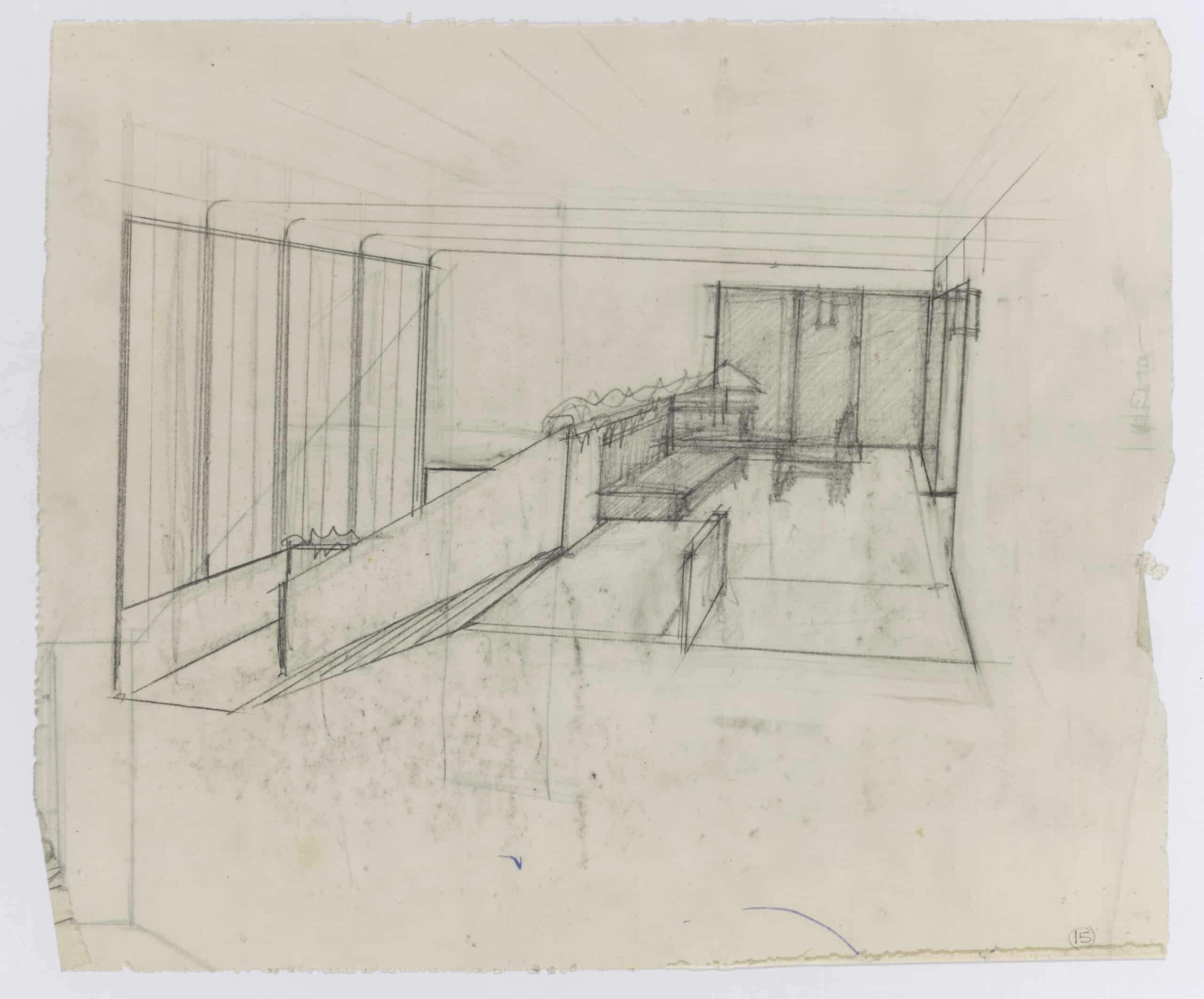

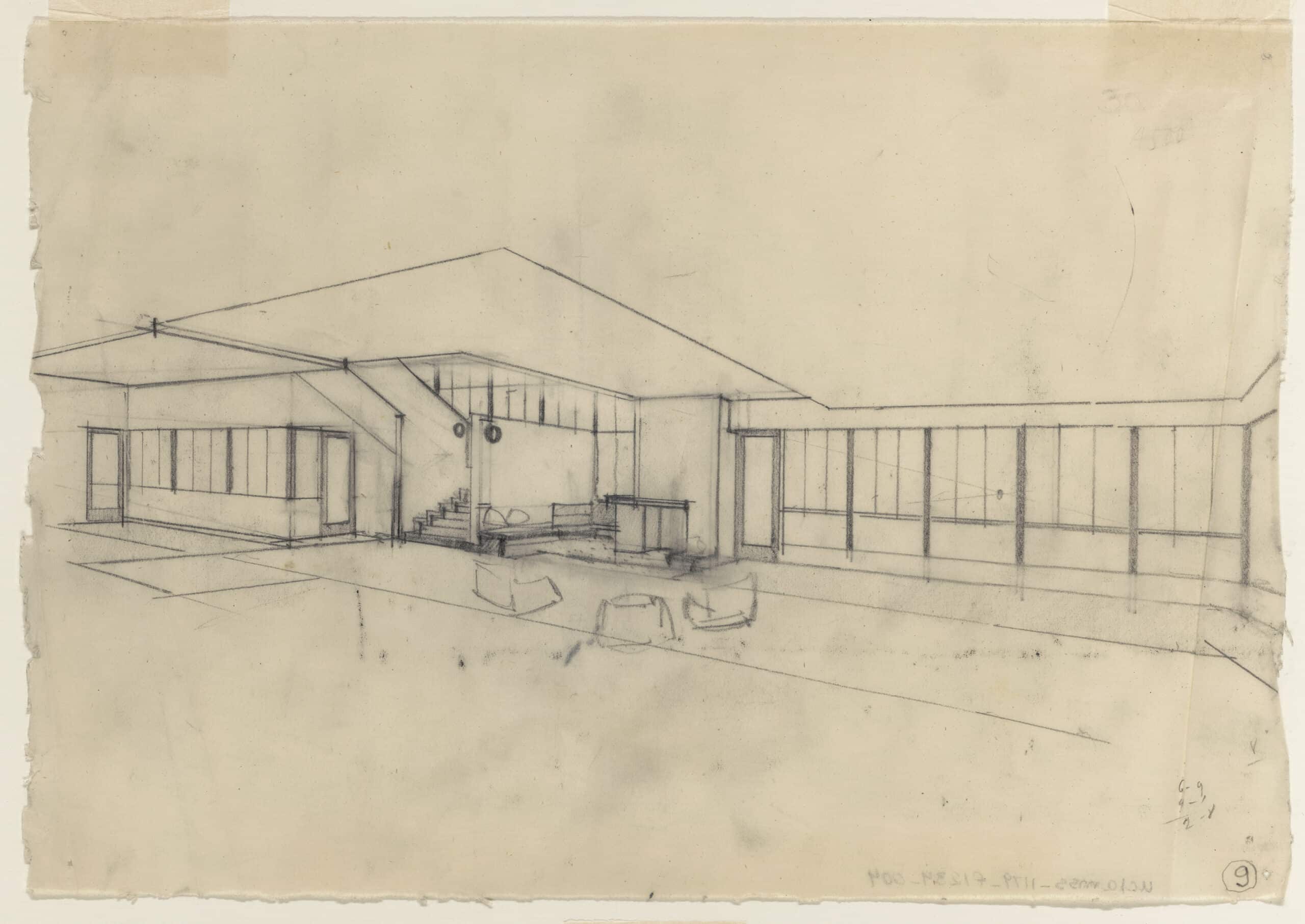

Functional and furnishing studies for interior space followed, envisaging movement and showing a mastery of spatial perspective. Lovell remembered his own most important contributions centring on daylight, drainage and the flow of air, with sleeping porches attached to each bedroom; on the house as a ‘social space’ where guests of all ages would mingle and linger; on the use of low, moveable, seating and tables in which posture was relaxed; and on removing the impediment to movement of doors, walls, or servants. He found it took some time for an architect from the Viennese bourgeoisie to fully accept the lack of division, enclosure and hierarchy. In rough studies, some made on large sheets of tracing paper in discussion over the drawing board, the interior experience of the social space and its fluent patterns of use were visualised, governed by the idea of uninterrupted open volumes, with only a few light, low-slung pieces of furniture: these are only faintly sketched on the sheets to suggest their mobility.

A sketch of the entry gallery looks at the possibility of placing a small office outside the door to the principal bedroom: this would eventually be built into the dressing room suite within, and the gallery left as an interior court of flowers. A tiny perspectival study through the living floor looks across the entire space to the South, intensifying the place of the staircase and hearth as a hub for the whole, with a seating alcove set into the towering shafts of light between them, and the famous automobile headlamps built into the wall for night lighting. Three exterior doors are projected at this stage of the discussion. Only the two to the east remained in the final plan, opening out to the external flower court and enhancing the sense of continuity in the western section of the room. To the east, Lovell and Neutra take advantage of the low ceiling created by the floor of the entry hall above to create a sheltered space and cabinetry on the north wall for a hand library. A very large sheet was laid on the drawing table to discuss the management of space in the main body of the social quarters. Looking to the west, we see a window appearing above the seating alcove—somewhat lowered on the final project—and a light screen separating the western section as a dining room—something that would be removed in the final plan to allow for an uninterrupted space. Dining tables were then placed on the porch leading off the end of the room to the north and bordering the kitchen and pantry. The treatment of the doorway opening to the wide passage between the kitchen and the guest suites across from the stairs to the right is still under study. This hallway, leading to the steps that descended to the gymnasium and pool below, was a fundamental element in the pattern of use. The systems were so innovative and the layouts and fittings so precise that Neutra drew and detailed all the working drawings by hand, and went on to contract and supervise the site and building work himself.

Dissemination, 1928–32

Given the nature of the experiment, Neutra invited Willard Morgan to photograph and film the entire process of construction, leaving behind an archive of the building in progress that is unparalleled for its time. Morgan’s formal images, taken with the view camera late in the process, became the iconic record of the project. Though professional studios were engaged for a small number of images on Neutra’s return from Europe in summer 1931 and summer 1934, when the landscape was better developed and the interior of the house slightly (and sadly) softened, the house rather wonderfully became and remained best known through representations of it, raw and unfinished, as it neared completion in the autumn of 1929.

The house was ready for public viewings, at which Neutra lectured, in December 1929. The first of Neutra’s extended presentations of the project—each very different in form, tone and content—appeared between May and November 1930 in four of the leading art and architectural journals of the United States, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and France. In March of 1931, the critic Roger Ginsburger in Paris followed up with a more reflective critical study, including a portfolio of extraordinary fine art prints from Morgan’s photographs, and a fully illustrated account of the building appeared at the same time in a special issue of Japan’s Shinkenchiku. Neutra then worked with his publisher in Stuttgart to present a definitive monograph, in a dedicated issue of their journal Moderne Bauformen for August 1932, just as photos of the house began to be seen across the United States as a fundamental element in the Museum of Modern Art’s ‘Modern Architecture: An International Exhibition,’ and in a large model built to Neutra’s specifications that was installed to culminate a visual history of human habitation in the new museum of technology at Rockefeller Center. At the same time, it circulated throughout Europe as the essential American work in the first edition of Alberto Sartoris’ enduring worldwide survey of Elements of Functionalist Architecture.

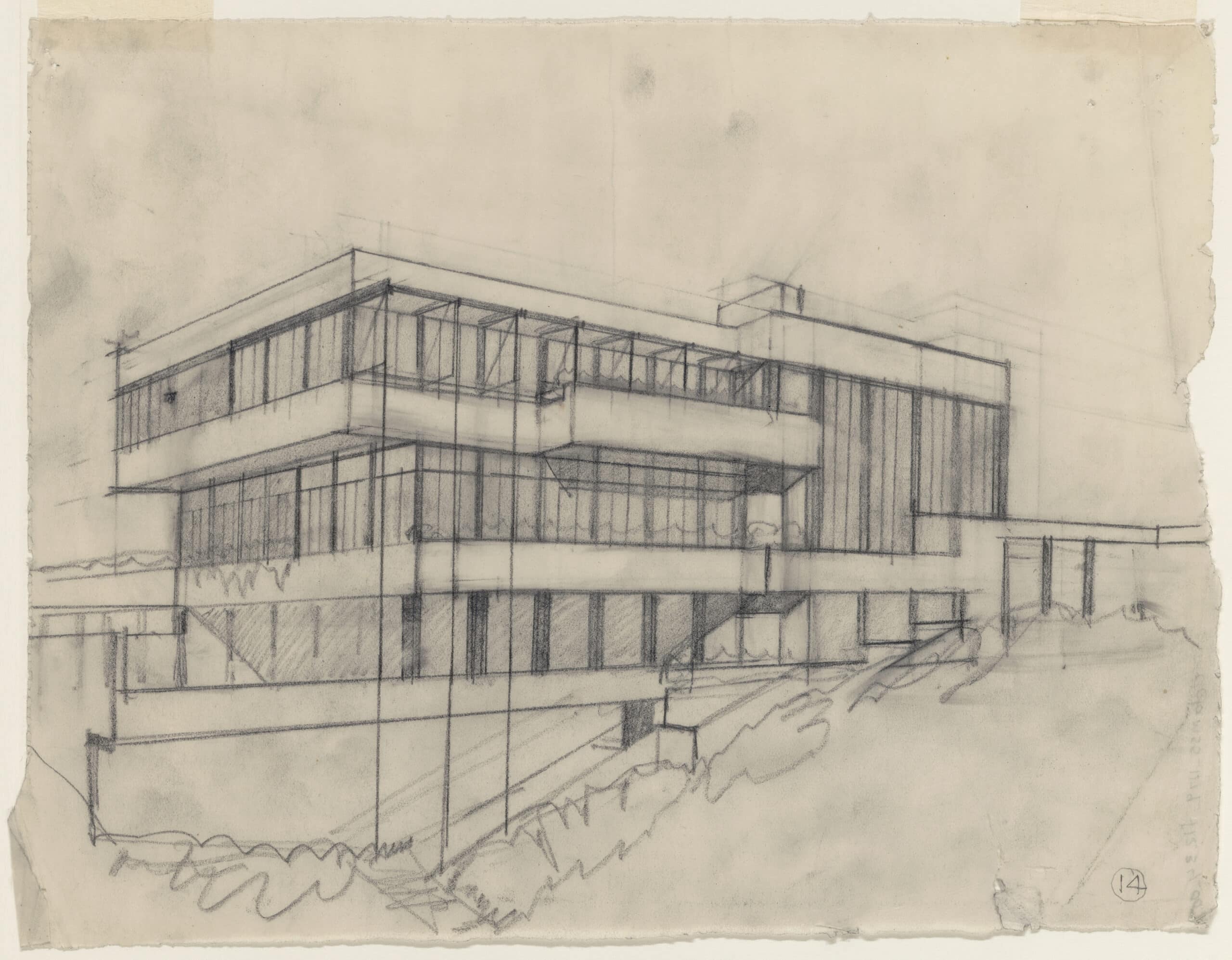

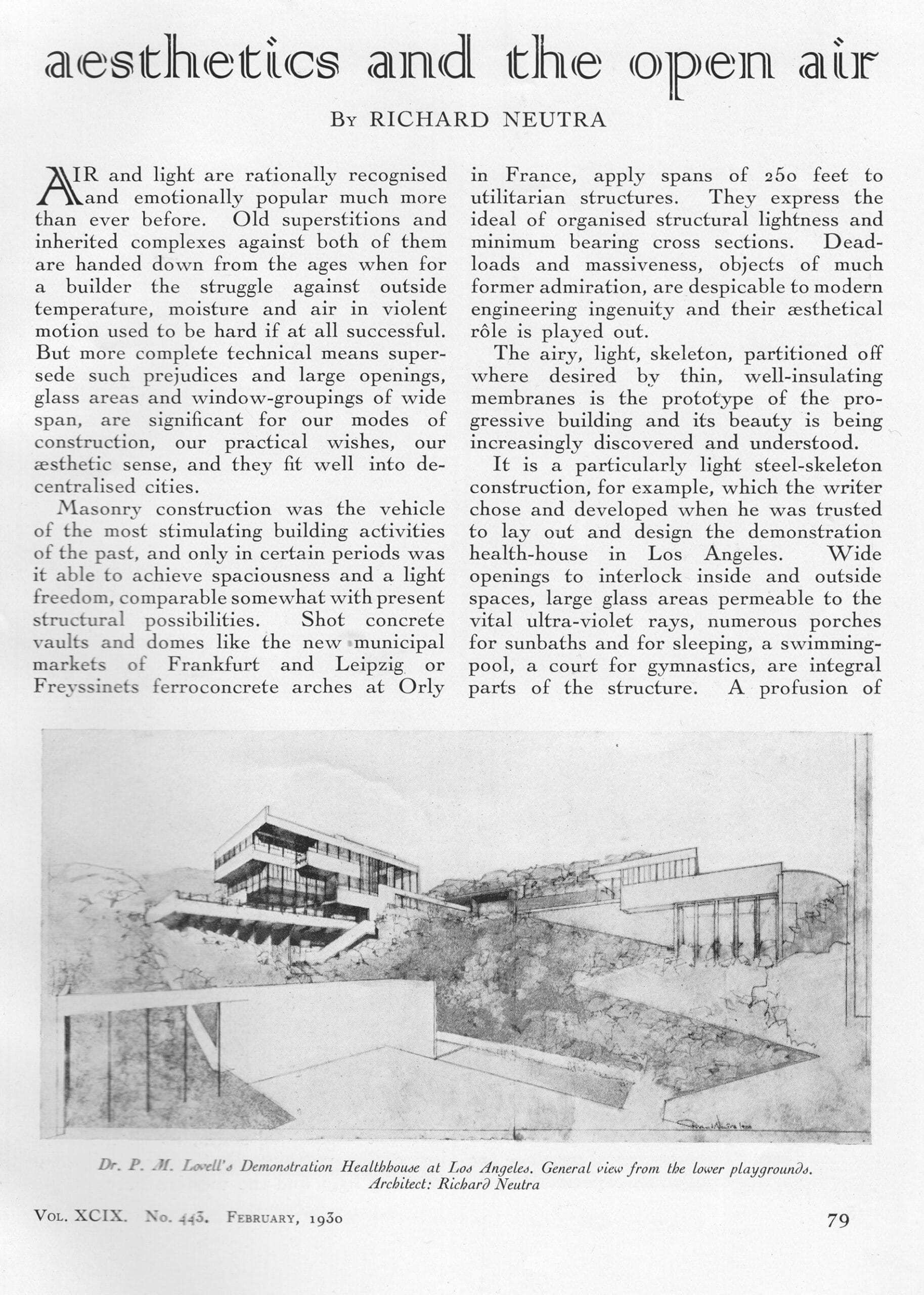

Before this extraordinary dissemination of photographic imagery into the architectural world, Neutra had chosen to make his first presentation of the completed work to a general audience, in a popular journal of art, and to show it not through Morgan’s construction photographs but by the pencil rendering in his own hand, which he appeared to have produce at the same time as his working drawings in April 1928. Thus it appeared in February 1930 in The Studio, the great illustrated monthly, with a readership across Europe and the United States (through a subsidiary in New York then called Creative Art), that had once revolutionised architecture and design as the organ of Art Nouveau and the Arts and Crafts Movement, and could now exemplify with the Health House the emerging new spirit in architecture. His accompanying essay on the aesthetics of the open air was something like a popular manifesto, addressed in the same everyday language as the lectures he gave to the public on the days of opening.

The above is a remarkable drawing. While some elements remained uncertain, the design of the house itself was fixed by April 1928. Hence—as a detail from the original sheets displays—Neutra could fully (and almost magically) visualise the work, 18 months before it first took shape on the horizon, simply through virtuoso handling of the weight, texture and angles of pencil points touching paper. The lines of the framework are sharply delineated, the contrast in sunlit luminosity between opaque planes of concrete and the transparent sheen of windows is precisely evoked, and shadows mark exact patterns of recession and projection under the noonday fall of light. While many of the iconic photographs of the built work will adopt the same viewpoint established by Neutra in this drawing, the limits of photography are clearly evident, since none represent the logic and effects of the house in its landscape with comparable fidelity or finesse.

Persistence: An Architect of Today, 1933–1946

Neutra had left California for Japan and Europe in the early summer of 1930, to study and lecture, uncertain whether his future course would bring him back to the United States. The shadows of repression were already falling across Europe while he and his family were in Vienna late in 1930, where he worked with Josef Frank on plans for the great middle-income housing exhibition of 1932. Gradually, they did return to Los Angeles, where in summer 1931, in the depths of the Depression, he reopened his practice with a new agenda, turning principally to the exploration of prefabrication, multiple dwelling systems, and standardisation to meet an urgent and growing housing need for all levels of income.

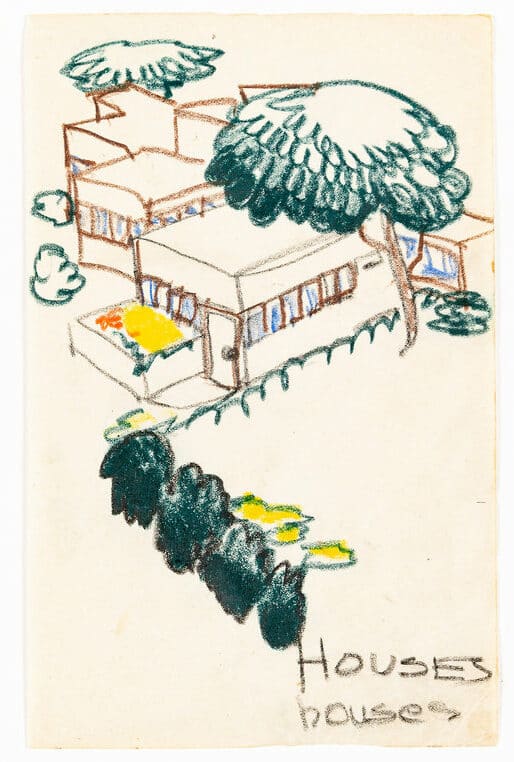

A drawing for an alphabet book for Neutra’s son shows one of these many ideas for clustered groups of dwelling, this one closely derived from his prototype house at the centre point of Frank’s Vienna exhibition; a handful of pertinent single models on these lines were produced in the course of the Thirties, using both steel and plywood (clearly anticipating the postwar Case Study programme with which he was initially and closely involved), along with an extraordinary set of three compact apartment houses for Westwood. But his ambition to work on a larger scale was not fully realised until the invitation to construct an entire new town for 600 households engaged in wartime industry at Channel Heights in 1943.

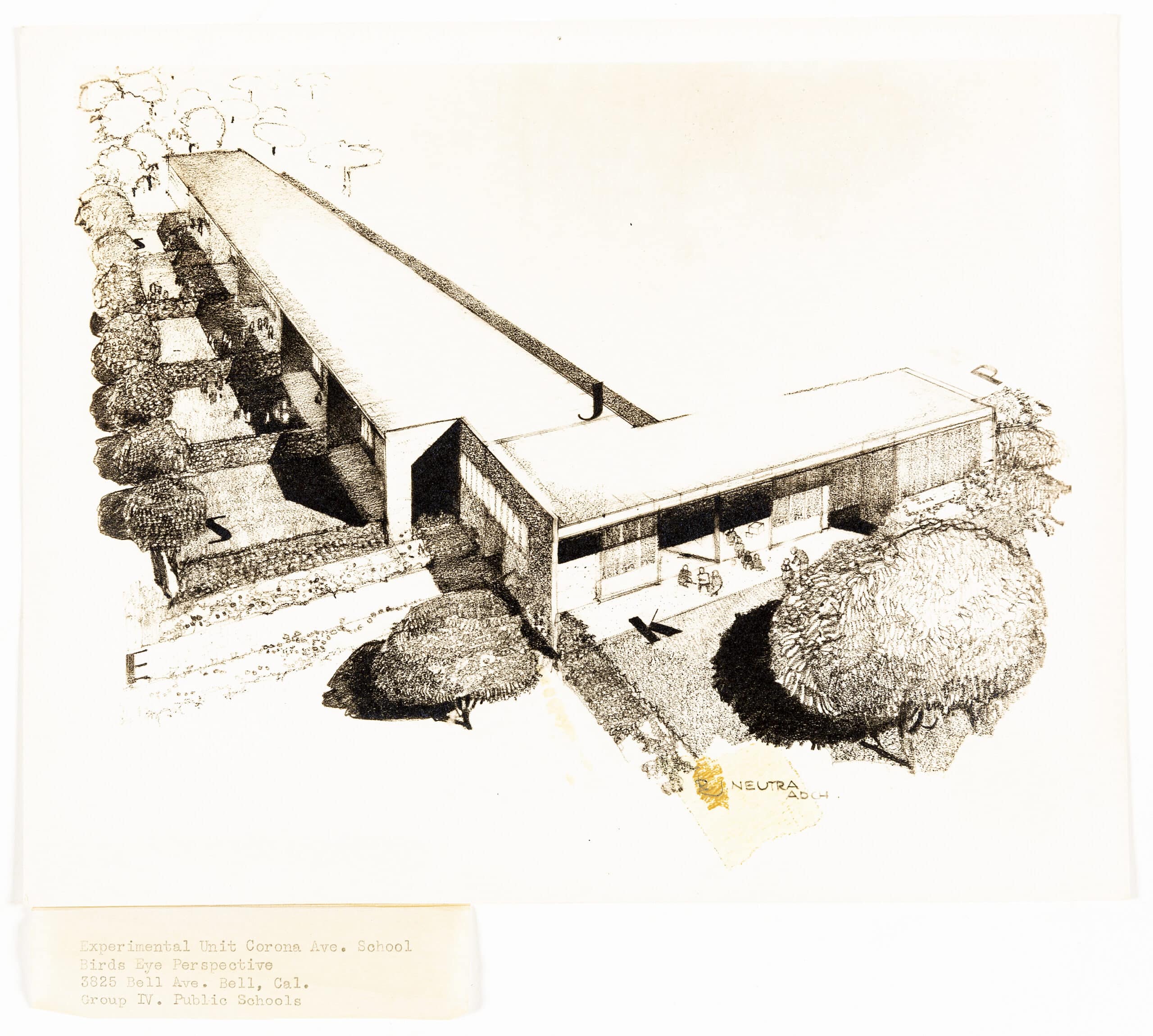

Meanwhile, he had adapted his model ring plan school for Rush City to begin a programme for schools and clinics, with his first built public endeavour—an ’experimental unit’ for a primary school at Corona Avenue—generating extraordinary worldwide interest. In that design, the formulation of the Lovell house as a site of learning through ‘activity’, and through the experience of movement between light and shade, open ground and shelter, played a fundamental role. The school proved to be the germ from which grew more than 30 years of Neutra projects for junior colleges, schools, and parks, community and medical centres throughout the US and Puerto Rico, providing the source of his exceptional postwar importance to the countries of South America.

He returned to the Lovell house in 1931 to furnish it with curtains and with two famous chair designs—one of which is sketched in the alphabet book; but in this atmosphere of social commitment, interest in the somewhat eccentric and expensive villa for Lovell as a domestic model for the United States slowly diminished, and he rather readily passed internal improvements for the Lovells to his former student Gregory Ain. But the intriguing possibilities raised by its constructive systems remained highly pertinent to the inquiries of the Thirties, especially in France: Jean Badovici of Architecture Vivante ran a portfolio on the house in autumn 1933, and its structural system was presented and discussed at length in Chantiers in the spring of 1934; while in Italy the editors of Casabella returned to it in January 1935 to launch an extraordinary two year series of articles on the work of Neutra, looking at the built projects that followed and developed from its example. The writers in Casabella recognised—as Neutra himself realised only upon completion of the Lovell house—deeper layers of healthfulness within them, as their natural, phenomenological and psychogeographic intelligence induced a therapeutic effect.

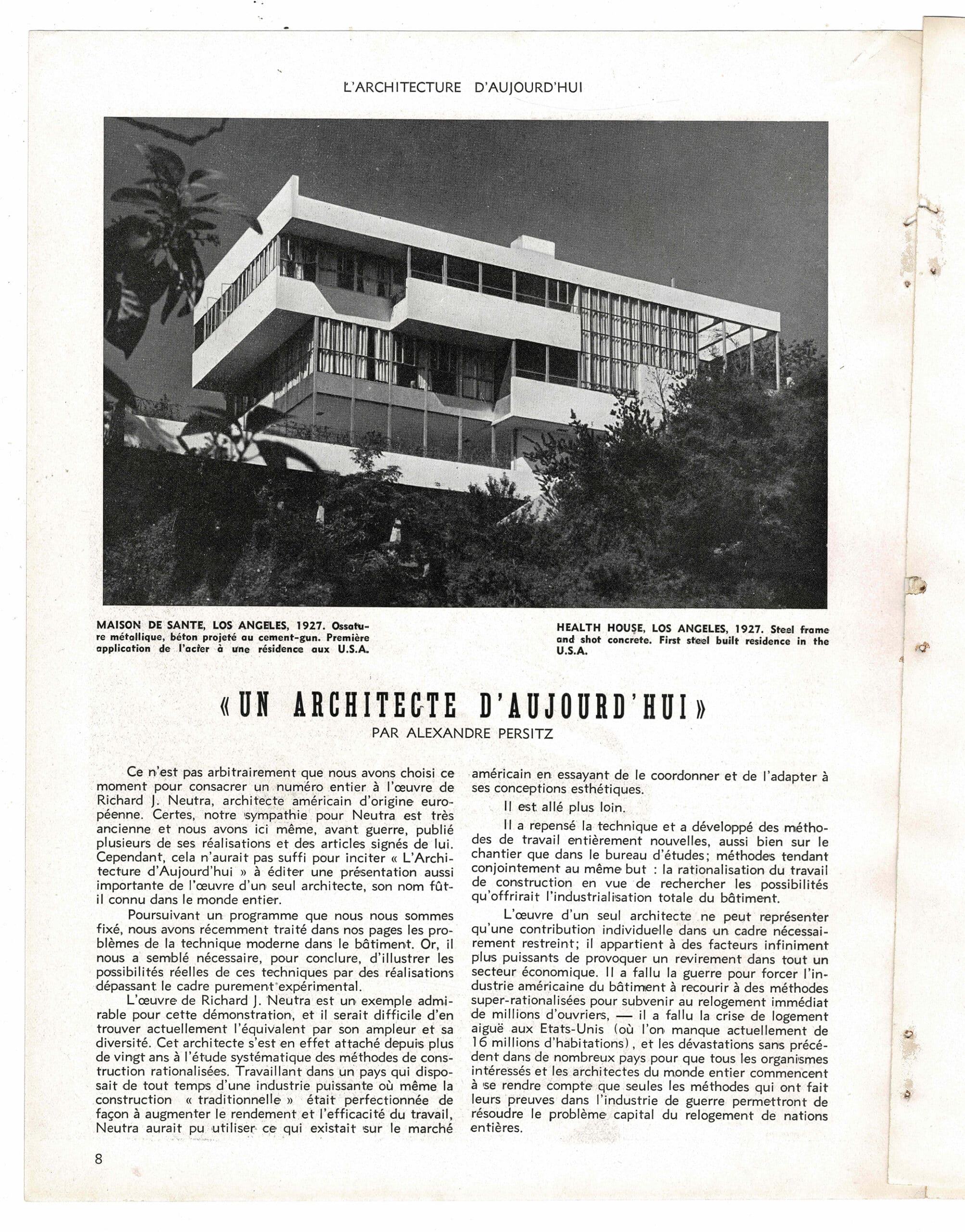

The Health House was still a fundamental point of reference to L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui when they studied it in detail for a comprehensive special issue on Neutra, issued just as the discussion of postwar reconstruction began in 1946. Alexandre Persitz reminded readers of the revolutionary impact the Health House—though now glazed, draped and overgrown—had upon the generation of 1925 and boldly asserted in his title that with it Neutra remained, nearly twenty years later, ‘Un architecte d’aujourd’hui.’

Notes

- Richard Neutra, ‘Aesthetics and the Open Air’, The Studio, vol.99, no.443 (February 1930), 79-84.

- Willy Boesiger, 1950, in Richard Neutra: Buildings and Projects (Zurich: Girsberger, 1951), 18.

The above text is adapted from Nicholas Olsberg’s contribution to the recently published monograph Richard Neutra and the Making of the Lovell Health House, 1925-35, ed. by Edward Dimendberg (London: Lund Humphries and Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2025).

All original drawings for the Lovell Health House are from the Richard and Dion Neutra Papers, UCLA Library Special Collections and are shown by permission of The Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design, courtesy of Raymond R. Neutra.

*

Nicholas Olsberg was Director of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal and founding Head of Special Collections at the Getty Research Institute. He holds an honours degree in Modern History from Oxford University and a doctorate in Nineteenth Century history from the University of South Carolina. He has written books on the work of Herzog DeMeuron, Carlo Scarpa, John Lautner, Cliff May and Arthur Erickson, has been a columnist for the Architectural Review and Building Design and has contributed to the curatorial programme of Drawing Matter Collections since its inception.