Richard Neutra at Drawing Matter

– Editors and Nicholas Olsberg

Richard Neutra trained in Vienna, for a time under Karl Moser and Adolf Loos, did wartime service in Serbia, and spent six years working first in Switzerland with the landscape architect Gustav Ammann; then in Berlin—for the last two years as project manager for Erich Mendelsohn; and finally in Chicago with Holabird and Roche, and at Taliesin with Frank Lloyd Wright, before opening his Los Angeles practice in 1925. He combined his studio practice with a career as a critic, lecturer, and writer, and also established himself firmly in the international discourse on functionalism through his activities in Japan; with CIAM, the Bauhaus, Das Neue Frankfurt, the Vienna Housing Exhibition of 1932; and through his continuing presence in journals, where his early California works—the Jardinette Apartments, the Lovell Health House, his own VDL Research House, the Corona School, and the Von Sternberg Villa—were immediately seen as foundational works in the international movement for a new architecture. His presence in the Americas was pervasive throughout the 1940s and 50s—through his working and middle-class community planning, public schools, and health centres for Puerto Rico, a series of renowned villas in the California landscape, and through constant traveling and public lectures.

The archives have suffered losses from depletion and a disastrous fire in 1963, and while Neutra was a masterly and inventive draftsman, and drew for pleasure on his travels, he chose for a long time to regard drawings as simply part of the process of communication with the client, public and builder, meaning that the durability of these drawings was not essential. As a result, the small selection of drawings that have reached Drawing Matter provide relatively scarce examples of his hand at work.

read all writings on richard neutra.

to view the complete drawing matter collections of richard neutra, click here.

Drawings, 1931–1959

ALPHABET BOOK, c.1931

Two leaves in pastel crayon from a child’s alphabet book created by Neutra, probably for his son Dion, who turned 5 in 1931: ‘Chair’, with a sketch of the bent tubular cantilever side chair developed for the Lovell House around 1930 and patented in 1931; and ‘Houses,’ demonstrating a staggered sequence of linked dwellings very close in form to his minimum demonstration house for the Vienna Werkbundsiedlung of 1932 (designed in 1930–31), and in contiguities to the ‘One plus Two’ and ‘Diatom’ prefabricated systems on which Neutra began working on his return to America in 1931 from a long sojourn in Asia and Europe.

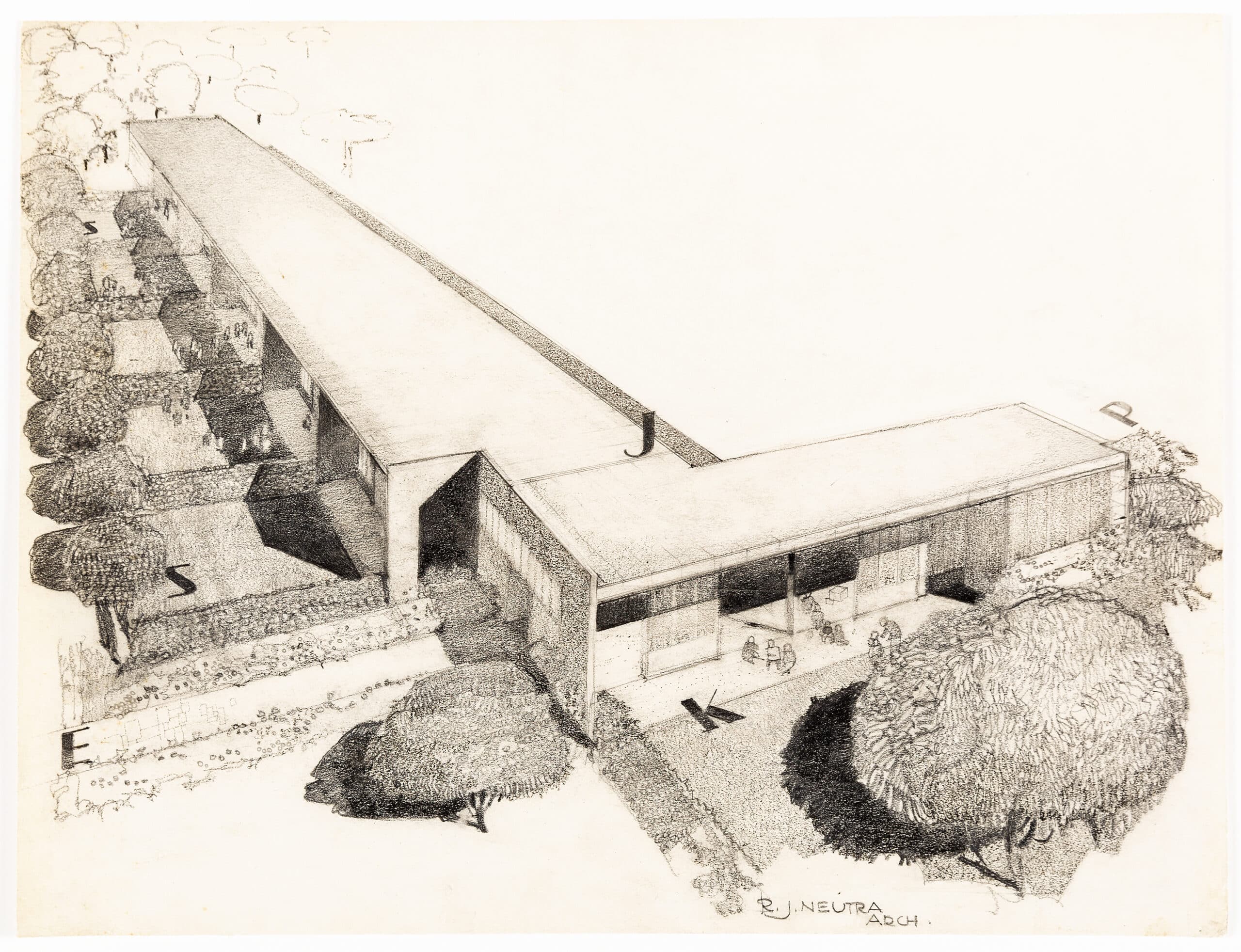

experimental unit, Corona Avenue School, Bell, California, 1935

A small group of drawings and photographs contemporary with this project for the addition to a public school of an open air-primary division and kindergarten. The design was completed in November 1934, and building work finished a year later. It was built in response to damages and dangers revealed by the Long Beach earthquake of 1933, but derives from Neutra’s earlier exploration of the ‘Ring Plan School,’ conceived as part of his hypothetical ‘Rush City Reformed,’ presented through model and drawings as one of the eight seminal projects in the Museum of Modern Art’s International Architecture show of 1932–34, and published internationally and in-depth in Die Form. Neutra notably explains the Corona project in depth in a special issue of Casabella in January 1936, almost immediately after its completion (a document that Giuseppe Terragni must have known as he commenced the similarly constructed Asilo Sant’Elia). A Drawing Matter scrapbook illustrates the pervasive presence of the school in the international literature of the first ten years of its existence. The project left a lasting and incalculable impact on architectural discourse and practice.

There are only a few visual documents in the Neutra archive from the time the school was designed, opened and first disseminated, so that the group in Drawing Matter becomes exceptionally useful in providing the source imagery of the project. A large pastel-coloured and peopled board, originally developed to illustrate the Ring Plan School and thus published in Casabella’s introductory Neutra monograph of January 1935, characterises the central idea of a ‘typical classroom for activity training’. It evokes but does not entirely represent the Corona Avenue scheme as finally designed. A rare bird’s-eye perspective in pencil, along with a photo-reproduced set of perspective, plan, and site plan, illustrate the form and functioning of the L-shaped scheme from its garden fronts, and two photographs show the corridor front of the project, and the kindergarten at work in the garden.

‘Prefabrication in Thin-Gauge Steel, Estate Josef Von Sternberg’, Northridge, California, 1935

The house for the film director Josef von Sternberg was for a large acreage of ranch land in California’s San Fernando Valley in which he and his star and companion Marlene Dietrich could seclude themselves and welcome friends within a protective plan. Neutra used curved boundary walls, silver paint, metallic and translucent surfaces, and reflecting pools to infuse the traditional shape of a California ranch compound with the aerodynamic sense of a speeding car and the diffused light and uncertain horizons, characteristic of the monochromatic sheen in von Sternberg’s cinema. Complicated and ever-changing design discussions began late in 1934; major design amendments were completed in March 1935; a period of rapid construction began in September, leading to the completion of the house on December 4th. Neutra describes it as the culmination of a ‘train of thought’ that began with his Beard House and California Military Academy in which construction would be simplified by using ‘prefabricated bearing walls of pre-assembled copper–sheet metal welded throughout–using flooring material for bearing walls.’

Although the Neutra archives at UCLA hold unusually extensive textual documentation—revisions, construction schedules, specifications for details and statements for publication and exhibition—only a single rough perspective sketch and a handful of detail working drawings are extant. This ink and pencil sheet provided the essential generative plan through which the final plan was enunciated, agreed upon, exhibited and circulated, along with a graphic sheet of printed axonometric views and photographs of the house in its raw state by the Luckhaus Studio. The villa—dominated inside by a two-story living and gallery space behind walls of opalescent glass, and with its moated watercourse heightening a luminous play of voids and solids—generated extraordinary European attention, notably in Circle (London), Casabella (Milan), and Stavitelske Listy (Prague), where a schematic version of the sheet appears.

The house was used by Neutra as a demonstration for contractors of numerous innovative systems: the deployment of sheet metal structure and cladding throughout, the water-cooling of roofs, and the concealed hygienic fittings of bathroom and kitchen. Von Sternberg conceived the house as a living gallery and studio for painting and sculpture, showing both his own work and his collection of African, Asian and modern works, notably a large group of Maillol and Archipenko, whose surfaces and lines are echoed in the shaping of the house and its landscape. There was a single owner’s bed and bath on the mezzanine, opening to a terraced pool. Though an emblematic example of the modernist villa at its inception, the house gained a second life in popular culture after the war as the home of Ayn Rand (from 1943 to 1951), and its purported association with The Fountainhead. It was demolished in 1971.

Case Study House 21, Los Angeles, california, 1947

A staple-bound set of over 100 sheets of blueprints, some oversize and folded, detailing construction and fittings for the last of Neutra’s four pilot projects for the first Case Study House programme of John Entenza’s California Arts & Architecture, published in the May 1947 issue with drawings and an elaborate text by Neutra describing its approach to modes of living, but never built. Neutra’s widely known experiments in prefabrication and compact dwelling from the 1930s were a critical point of reference for Entenza’s programme. The house—conceived largely as a wood and glass frame finished inside with durable washable surfaces—derived from Neutra’s hypothetical Alpha and Omega Case Study houses (published in October 1945 and March 1946), which first advanced those ideas.

It was planned as one of a linked cluster of three units at different scale and orientation for the north-east corner of the large site above Santa Monica Canyon that had been acquired by Entenza to demonstrate the programme, and on which his own house by Eames and Saarinen, and the Eames Home and Studio would appear in 1949–50. Commissioned by the novelist and screenwriter Roy Huggins, it was designed to serve as a home for a young family with secluded writing and sculpture zones for him and his wife, and a permeable relationship between indoors and outdoors, and between the children’s outdoor space and that of its neighbour (a larger unit built for the Bailey family, designated CSH 20 and published on completion in December 1948). This extended example of details and specifications—a rare, perhaps unique, survivor for Neutra for the type and date—indicating innovative material choices and maximising space through inventive fittings (such as folding and sliding doors) enunciates many of the systems and techniques that were eventually deployed in the construction of the Bailey house.

Click here to view the album in sequence.

NEUROLOGICAL SANATORIUM FOR UMBERTO DE MARTINI, ISEO, ITALY, c.1959

An example in crayon of Neutra’s freehand studies for structure within landscape, akin to his voluminous travel sketches, through which, late in his career he would use to methodically test vistas, sun orientations, and the colour and texture relations of built work to topography and vegetation. The drawing shows a section of the front range of patients’ rooms on the boundary of a never-realised project for a mountain sanatorium north of Milan, for a fashionable physician of uncertain reputation. It develops ideas for layers of a terraced dwelling that build on his earlier work, most keenly expressed in the Holiday House project of 1948. Numerous, more elaborate, painted views of the scheme have appeared from private sources, but no record seems to appear in the archive, and little is known about its scope or fate, except that it never appeared.

Gettysburg Visitor Center, Pennsylvania, 1958-62

The project was part of Mission 66, a programme to render National Park facilities in the USA in a modern vocabulary for modern times. Neutra—in part with his associate Robert Evans Alexander—undertook two parts of the scheme: the remarkable complex for visitors and Park Service employees at the Painted Desert, and the extraordinary reworking of the visitor centre, offices, entry landscape, and rotunda for the 19th century painted Cyclorama at the Gettsyburg Civil War battle site. This unique drawing, dating from the completion of a second design in June 1959, is the sketch perspective from which a larger pastel rendering was developed for presentation and publication—the original is within the archives of the National Park Service. Neutra’s own drawing—stippled and shadowed—suggests elements of the scheme that the promotional and overdramatised pastel cannot: stone walls based on historic prototypes, the mica particles sprayed on to cement surfaces to catch light, the emphasis on a vertical pattern to the ribbed building, the absence of a structural frame, the exact rendering of vegetation and rock, and the extraordinary openness of the outdoor assembly space under its canopy, which Neutra conceived as a forum for public addresses on peace and cooperation. Despite much protest, the building was recently demolished.

ImPrints and miscellaneous