The Sasada Lab

For the past two years, our Writing Prize has attracted a large number of thoughtful texts from participants all over the world. This year we partnered with the Architecture Foundation to sponsor one of their three writing prize categories. The Drawing Matter category, titled ‘Architecture and Representation’, invited entrants to submit a short piece of writing on a drawing or series of drawings that they had studied or made.

The relationship between our hands and the production of architecture is a rich, complex and somewhat mystical exchange. To Kant, these formidable tools are ‘a window to our mind’. [1] Their crafted physical outputs offer a lens into both a designer’s processes and thoughts. Anyone who is creative is aware of the compelling nature of a sketch, with its ability to draw you into an idea, capture your attention and transport you to an alternate reality in an abstract yet utterly overwhelming way. In an ever-more digital era, amidst the cacophony of hyper-realistic renders and virtual realities that dominate architectural media, such intense feelings are few and far between.

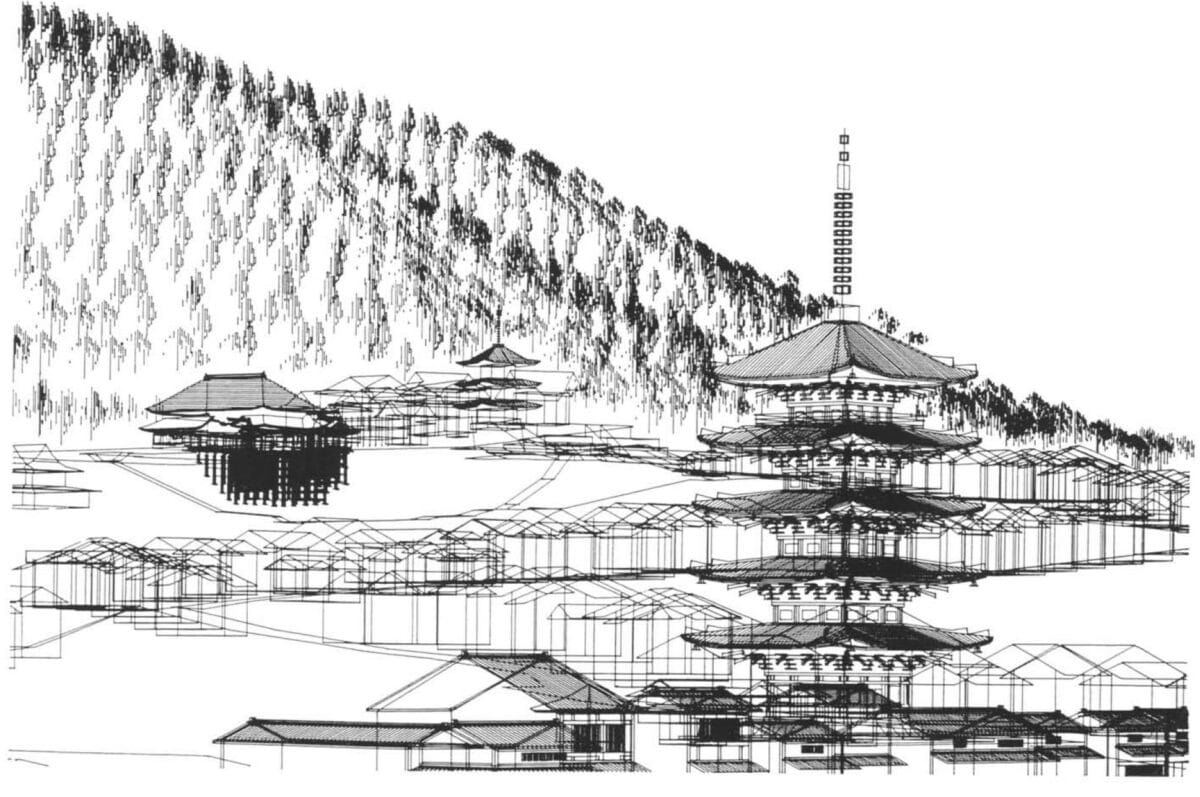

Tsuyoshi Tee Sasada posited in his text for the journal Computer-Aided Design in 1987 that computer graphic development should not search for ‘realism’ but for ‘a realism of drawing’. [2] The Sasada Lab was a prominent Japanese CAD research unit during the 1980s and 90s that aimed to ‘develop design media that informed the designer and the design with the goal of improving the final [outcome]’. [3] An early output of the Sasada Lab was a paper on ‘drawing natural scenery’, which explained the challenges of digitally replicating drawings that convey the irregularity of natural landscapes whilst minimising the use of computing power to capture the essence of the subject in a manner akin to a hand-drawing; a so-called ‘realism of drawing’. [4]

These drawings, in a somewhat picturesque style, frame Japanese cityscapes with their surrounding topographies ambiguously. Like a sketch, they engender our attention through an absence of resolution; they are real because we have to make them so. The economy of the wireframe drawing is responsible for these characteristics and produces a variety of effects to that of sketching, such as the subtle ‘blending’ of architectural and non-architectural space, which strips the drawings of visual hierarchy. This is not by chance. The Sasada Lab’s precise dissection of the processes of hand drawing was the principal reference for the programs they developed, and resulted in compositionally rich, interrogative, and – through the digital layering of information – intensely analytical drawings.

These drawings are not about making our digits more digital, outputs more realistic, or computers free labour. [5] They are about something far richer: emulating the qualities designers attempt to achieve through their hand drawings. The Sasada Lab drawings are fundamentally about being immersed in a world that is full of opportunities and suggestions, not statements, and should be applauded for their frugality, ambiguity and speculative qualities. The intense feelings that these digital drawings evoke are refreshing and poignantly illustrate that whilst the ‘hand is a window to the mind’ the digital can also be a window for the mind.

Felix Wilson is an architectural assistant currently practicing at Fraser/Livingstone Architects.

This text was selected as highly commended in the Drawing Matter category, ‘Architecture and Representation’, of the Architecture Foundation Writing Prize 2022.

Notes

- Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), p.149.

- Tsuyoshi Tee Sasada, ‘Drawing Natural Scenery by Computer Graphics’, Computer-Aided Design 19 (1987), p.212.

- Tsuyoshi Tee Sasada, ‘The Sasada Lab Department of Environmental Engineering Graduate School of Engineering’, ACADIA Quarterly, Vol.17, No.4 (1998), p.5.

- Sasada, ‘Drawing Natural Scenery by Computer Graphics’, p.212.

- Daniel Cardoso Llach, ‘Perfect Slaves and Cooperation Partners: Steven A. Coons and Computers; New Role in Design’, Builders of the Vision: Software and the Imagination of Design, (New York and London: Routledge, 2015), p.50.

– Matthew Blunderfield and Dank Lloyd Wright