Tolerance

Too many people have talked about how profoundly the production of architecture has changed in the wake of the digital revolution. Far fewer have noted how architecture has resisted the seductive flourishes of digital production and maintained a dogged continuity with social and historical space. Bricks remain bricky even when laid by a robot. Timber remains fibrous despite the scorched traces of the laser cutter. These remain the rare marriages of new technologies with ancient tectonics, for architecture continues to evolve within the present, dragging a past into the future full of conflicted meanings and associations.

Occasionally architecture is also revolutionary, rupturing with the past to establish the unencumbered new. Paper architecture has long been a byword for the avant-garde, for the unbuilt as much as unbuildable architectural rhetoric. Yet even in revolution, the representation of architecture uses the same abstract notation of orthographic plans, sections and elevations established during the Renaissance. As with all architectural (r)evolutions, the primary battleground since that time has been in drawings and, dare I say it, on paper. The architectural drawing sits ambiguously between revolution and tradition.

The past three centuries have seen a complete transformation in industrial production and society and, in the last twenty years, communication has done the same. Despite these changes, the architectural drawing–the plan–has endured: architects still examine the plan to understand its underlying spatial and conceptual ideas. This survival places the plan in the realm of a quasi-language rather than professional technique, a system possessing its own rules and codes, unlinked to the phenomena it represents. In this case, the common language that bridges the architectural imagination with a constructed reality lies in the conventions of the plan. Like musical notation, the architectural drawing is composed and read by the initiated, a semi-open code of ideas and instructions specifying exact execution or inviting interpretation. It is a means of creation, production, reproduction, execution and one of very few means of production to endure despite more than five centuries of changes in culture and technique–from steel point and quill to graphite, mechanical ink pens and finally CAD, which replaced the hand in the closing decade of the twentieth century. Augmented realities and AI now put it all into question.

The first time I entered an architectural office was in 1989 for a summer job I had taken before starting architecture school. The office of around forty people was quiet and busy with designers either standing or sitting on tall stools and hunching over drawing boards arranged at assorted angles to suit their users. My first task was to change fire exits on a plan from single doors to double doors. A simple if rather banal task for a young would-be architect. I was shown to my board and handed my first Rotring pen, scale ruler, blue clutch pencil and, crucially, a small packet of razor blades to erase the offending doors scattered across the A0 tracing paper drawing.

Like all skills required of a good draftsman or woman, scraping away a very thin layer of ink without damaging the paper requires practice. I clumsily gouged away more paper than ink with the razor and eventually cut through my finger. The rest of the day was occupied with removing dried blood from the complex field of fine black lines that formed the primary ground floor plan, known as the general arrangement drawing, or GA for short. Needless to say, I developed the art of erasure ahead of the full range of drafting skills, but for the record, in time, those also improved.

Over the following five years, both at architecture school and in offices, we would draw for several hours a day, gaining speed and precision alongside an awareness of the nuances of architectural drawings. Ink on trace was the modus operandi of a British practice, but occasionally one would use film, a heavy-duty translucent plastic sheet that looks like tracing paper but behaves in a completely different way. Film is tough stuff. It was used for long-term drawing that would be updated over years – say, the ground plan of a major building. But film does not absorb ink, it stays liquid on the surface for what seems like an eternity when facing a deadline, and it can be erased with a special rubber (or eraser, probably electric, for our American colleagues). At the other end of the scale, in smaller offices, one would use pencil on detail paper, thin and soft, a cousin of tissue paper favoured for wrapping luxury goods. With pencil and detail paper (mounted over a sheet of cartridge paper backing to soften the stroke), the work of the draftsman felt more personal, more subtle. One could do the whole process with a single tool. Light construction lines ghosting out the drawing followed by a firmer stroke especially at the start and end of each line while rotating the mechanical to keep the point sharp. With pencil, not only was drawing faster, but the sheet of paper acquired a texture and reflected the hand of the author more directly. One could discern the work of the manic, rushed architect chasing construction site deadlines from the subtle marks left by the reflective practitioner. These were the tools of our trade.

It is worth defining what kind of plans we are looking at. In German, the plan refers to all the technical drawings leading to construction, whether horizontal or vertical. In English, the plan refers specifically to a horizontal section while the whole set of construction documents, including plans, sections, elevations and construction details, is commonly referred to as working drawings. Adding the verb ‘working’ lends a particular kind of technical and ethical purpose. These are not objects of contemplation, of aesthetic quality; they are work and they represent more work to be done. They may be seen as a means to an end and nothing more. But of course this has never been entirely true. The architect has always invested the working drawing with more than pure information and data to share with builders. Either deliberately or inadvertently, the working drawing is laced with conceptual and ethical values that underpin the architecture. The architect’s plan combines everything that is common to the language of architecture, its traditions and conventions, with what is personal and unique, like a form of handwriting.

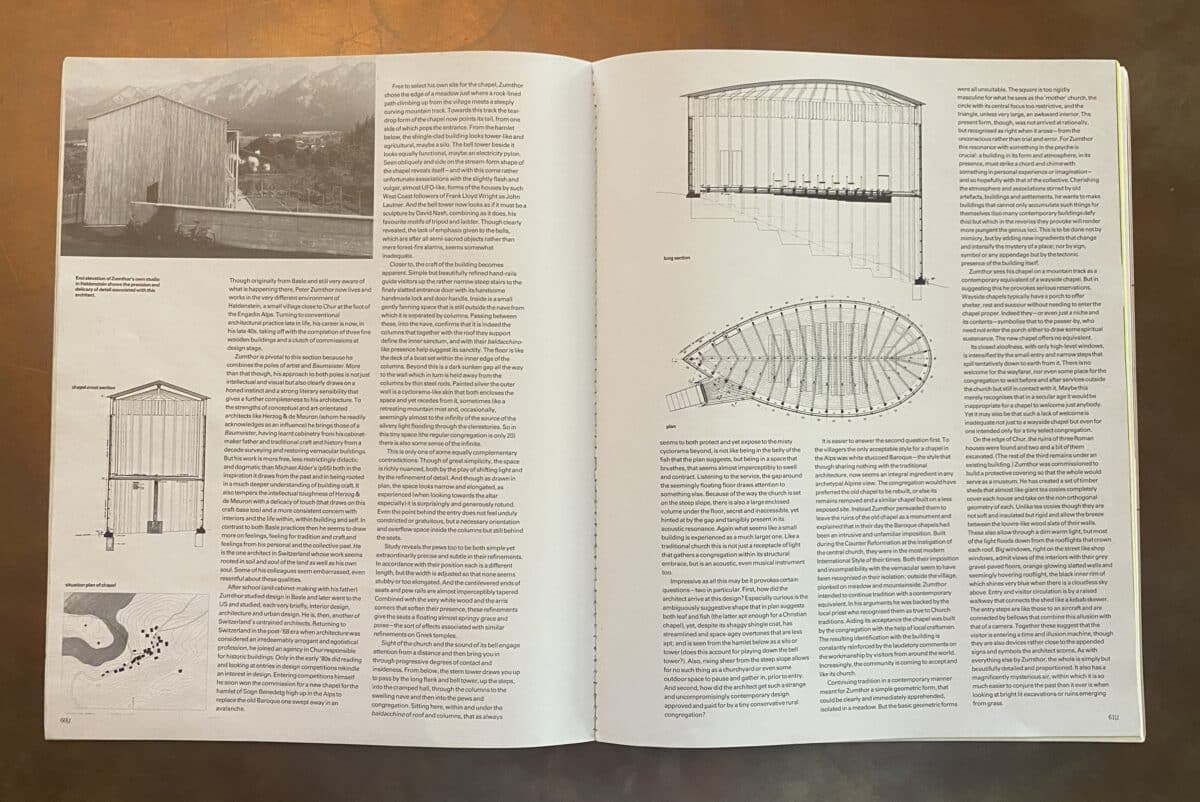

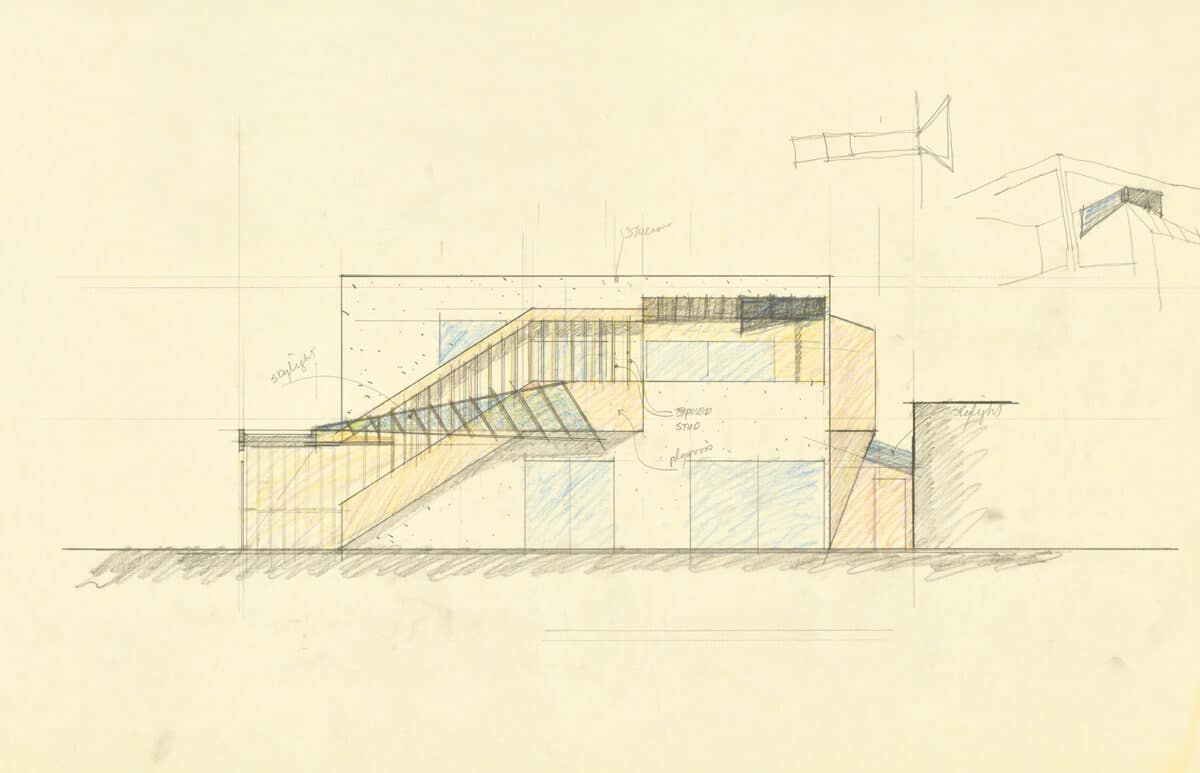

As a student, seeing Peter Zumthor’s drawings of Saint Benedict Chapel in Sumvitg, Switzerland (1989), published in a 1991 issue of Architectural Review, was particularly memorable for their combination of precision and atmosphere. These were not black lines on white but shades of grey lines on grey background. I had not seen the building (and still haven’t to this day), but I believed (and still do) that the qualities of those drawings would be found there, regular but sensual, austere without being cold. Like many of my peers, I had fairly promiscuous architectural taste and studied Frank Gehry’s early work with equal enthusiasm. One doesn’t need to travel from Switzerland to LA to find the difference between the timber buildings of either architect. Both work predominantly with softwood frames, but their construction traditions and inventions couldn’t be further apart, and their working drawing techniques bring out that difference. Although both use pencil, Zumthor’s drawings are above all complete works in their own right. The mise-en-page perfectly places the subject on the sheet. Layers of overlapping lines, from barely visible grid lines to the heaviness of elements cut by the imagined section to the regularity of the hatching, speak of patience, resilience. Nothing is left to chance. Tolerance has certainly been considered, but this is dimensional tolerance, technical tolerance where it is required by the material that masks another kind of intolerance. Every element in the architecture has been considered and honed. Mistakes do not form part of Zumthor’s architecture. In LA, however, all of Gehry’s lines are broadly equivalent, democratic and, above all, quick. The drawing shows what is necessary and no more. There is no time for hatching. This is no meditation over reduction and craftsmanship but instead fast, intuitive riffing on well-known commercial vernacular. The notation and construction are economic, even expedient, the results refreshingly direct. There is plenty of tolerance both dimensionally and also ethically, allowing the carpenter to complete the task according to prevailing rules of commercial construction. Gehry’s working drawings are loose and opportunistic. But that shouldn’t confused with less attention to construction. On the contrary, both architects show a deep knowledge of materials and a wider socio-economic context. Gehry’s apparently laconic plans embody the tradition of American framing just as profoundly as Zumthor’s drawings suggest the craftsmanship for which he and the Swiss are so famous. The drawing is not only a means to an end, it implies the means.

‘This is how space begins’, writes Georges Perec in the opening of Species of Spaces, ‘signs traced on the blank page’, but such direct, unmediated creation is no longer possible. When I finished my studies in 1997, the craft of architectural draftsmanship already seemed about as useful as calligraphy. Today, paper is the final resting place for the line after a life of digital gymnastics. Layers, classes, attributes, nurbs; so many decisions before space can begin. The stroke of the pencil or pen has been replaced by the click of the mouse, the rectangular expanse of the drawing board by the infinite zoom of the screen. And yet the orthographic projection of the plan remains the lingua franca of architecture. The plan is both the thinking and the letting go, the conception and the communication with the maker, taking the architectural imagination into the world line by line. Although it is no longer drawn in the original meaning of the word – that is, by pulling a pencil across a surface – the plan retains a uniquely autonomous position in architecture between the architect and the built architecture. The great conceit of the plan – to imagine the work of architecture sliced horizontally to reveal simultaneously its solids and voids, its surfaces and nodes – is an improbable but powerful abstraction. After the point, the line is the most basic Cartesian form, yet in the context of the plan it is capable of representing a multitude of spatial ideas. The line may signify the physical and the abstract; it may suggest a surface, a gesture like the spread of a trowel or an invisible legal boundary. The line can suggest changes in the states of matter between mass and void or between a liquid and its container. Or the containment might exist in the lines themselves as they come together to make the working drawing, a register of a temporal dimension that encompasses both the pre-existing and the as-yet unrealised anticipated future. The drawing contains a latent architectural order; densely layered or monolithic, dotted to float above or thickened to suggest the imaginary slice through plaster, steel or concrete. The plan is the making of the architecture. It is the instrument by which the architect records what is found and proposes what will come. The plan is the means of conception and communication. In the end, the plan is not so much musical notation or handwriting as it is the fingerprints of the architect, both universal and unique. More than the sketch, which communicates intuition and first thoughts, the plan bears the imprint of the whole process through to every decision, whether invented or imposed from the outside. The working drawing contains the sum total of the architect’s thinking, time spent, compromises, imagination and skill synthesised and distilled in lines on paper.

*

This text appears in Tom Emerson’s recently published book Dirty Old River (Zurich: Park Books, 2025), 60–65. It was first published in 2013 in Der Bauplan: Das Werkzeug des Architekten (The Working Drawing: The Architect’s Tool) by Annette Sprio.

Tom Emerson studied architecture at the University of Bath, the Royal College of Art, and the University of Cambridge. Alongside his practice 6a architects, which he co-founded with Stephanie Macdonald, he is a professor of architecture at ETH Zurich, where he leads a research and design studio exploring the relationship between making, landscape, and ecology.

– Fabio Colonnese