Trevor Dannatt: St Mary’s Grove — Through the Door

This is the sixth part of Adrian Dannatt’s series of reflections on his family home, frequently remodelled and extended over 45 years from 1955, by his father, the architect Trevor Dannatt. Read the introduction to the series, here.

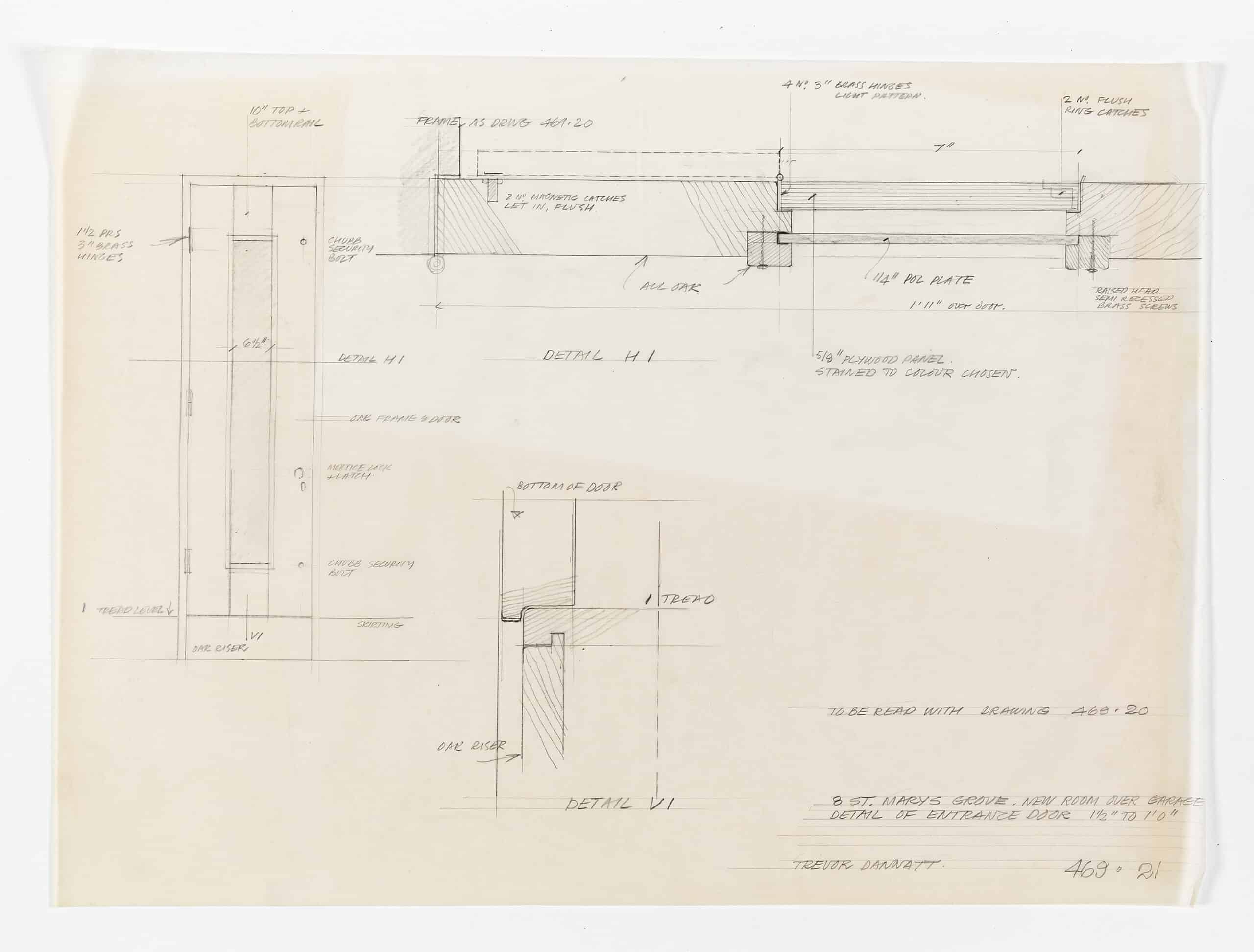

Entering the house the first thing one sees is the entrance door to my father’s study—the second floor of his extension, above the garage. Trevor was rightly pleased with this notable portal, its very narrowness is as if tailor-made to his own thin, long Giacometti-like frame. Admire the judicious choice of wood, now nicely aged, and especially the central glass panel with its hinged, red-painted wooden shutter. For my sister and me, and visiting friends, this was a central part of our childhood; when the red panel was closed it meant Trevor should not be disturbed, he was at work within, if it was open and one could see through the glass, we were welcome to visit. Next to his own door is an antique Saudi Arabian one picked up in Riyadh when supervising the building of his King Faisal Conference Centre and Hotel. These two juxtaposed wooden doors give some idea of the sophistication and historical range of his aesthetic sensibility.

A detail of the famous (perhaps notorious in our household) wooden ‘privacy panel’, Trevor’s version of the ‘green baize door’. That red is, of course, the obvious colour to make sure people stay away. But it is also a classic architect’s shade of the era, somewhere in that elegant zone between late modernism and postmodernism; a colour as suited to Gae Aulenti and Aldo Rossi’s furniture as Jim Stirling’s ‘Red Trilogy’ or the red-stained wood in Siah Armajani’s ‘Reading Rooms’ from precisely this period, 1977–1984. The more I think about this door the better it becomes, as both a design and human metaphor, with surely something of my father’s deadpan wit, humorous exaggeration, in its bright red flag warning; ‘I am an old curmudgeon, keep out, but not really.’ There is also the beauty of its finish, that lovely little bronze latch for opening-and-closing, a detail also to be found at Pitcorthie House which he designed in 1966.

Entering the Study

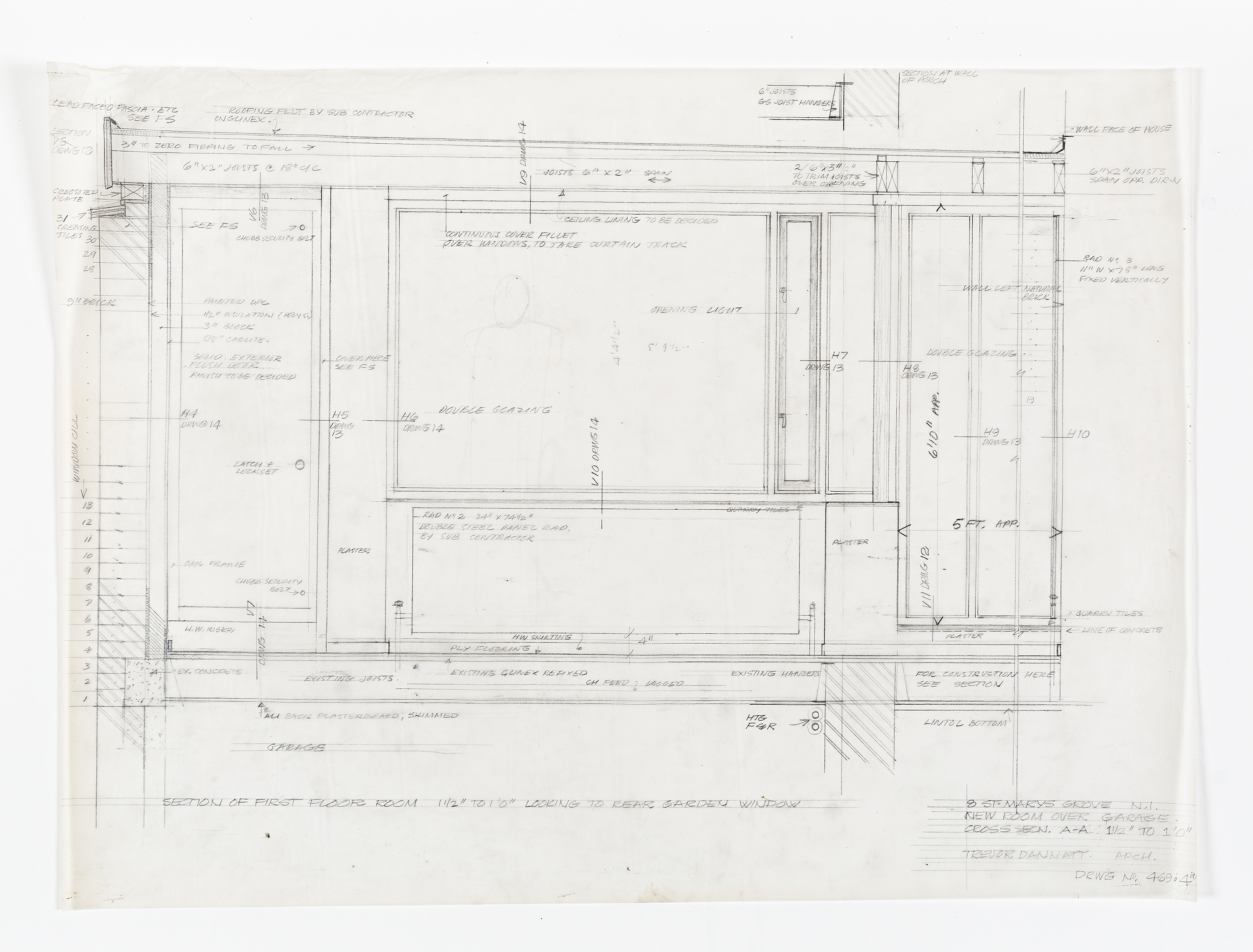

Entering Trevor’s self-designed studio, he hoped one would immediately notice (or merely sense) that the original outside brick wall of the Victorian house had been retained, unchanged, unpainted, exactly as it was outside. He was particularly proud of this continuity, a singular surface to make inside and outside read as one. He also just loved the gloomy texture and age of the old wall, weathered for a century and now brought within the warmth and shelter. I often point this out and I am surprised how unimpressed most visitors prove, ‘that’s the sort of thing that only an architect would understand or find remotely interesting.’ So be it. For to quote Genghis Kahn: ‘The strength of a wall depends on the bravery of those who defend it.’

The use of this continuous worn wall, the exterior as interior, the old within the new, the dark ordinariness, established for Trevor the ideal tone, intention, of his extension. I enjoyed a recent BBC R4 programme The Hidden History of the Wall by the cultural sociologist Rachel Hurdley, which dealt with ‘what walls tell us about how we live’ and how ‘walls which we often take for granted, define the spaces we inhabit’.

If the outside-inside wall surely conjures a touch of Wright, whom Trevor memorably met through his great friend Edgar Kaufmann Jr, so does the restrained woodwork of the windows, the spacing, pacing. And the blinds Trevor designed, deployed, and adjusted by a system of cords, seem very Taliesin, especially in their somewhat Japonaiserie textured material—what is this stuff?

Curiously enough, in my sixty years living in this house I never once saw these blinds closed. In fact, I don’t think I had even noticed them before; I drew them (drawing matters!) for the very first time in order to take this photograph. Did Trevor ever draw them, were they ever used? I think not. And why are they here when this particular corner of the house receives barely any light, let alone direct sunlight? I think Trevor must have loved the material and design of his blinds so much that he installed them regardless of necessity. A full forensic investigation might be able to discover the nature of this fabric, flecked like handmade paper, surely oddly elegant. They manage to be ‘timeless’ whilst also totally late 1970s, the sort of thing Bruce Goff might have installed in a Kyoto hotel; an altogether pleasing discovery, I shall draw them regularly just to admire that wall of paper… or whatever.

– Adrian Dannatt