Unveiling the Enigma: Jan Henriksson’s Örebro Riksbank, 1987.

– Felicia Liang and William Wikström

Jan Henriksson playfully crafted an evocative scenography for the financial world of the 1980s, deviating from the pursuit of uniformity with various forms that break free as autonomous figures within a larger context. Two of Henriksson’s drawings for the Central Bank, Örebro Riksbank exemplify his unique position in 20th-century Swedish architecture. These two drawings manifest his mastery of complex spatial arrangements and a profound understanding of symbolism, offering a glimpse into his evocative worlds, and the tensions and contradictions that prevail in his architectural language.

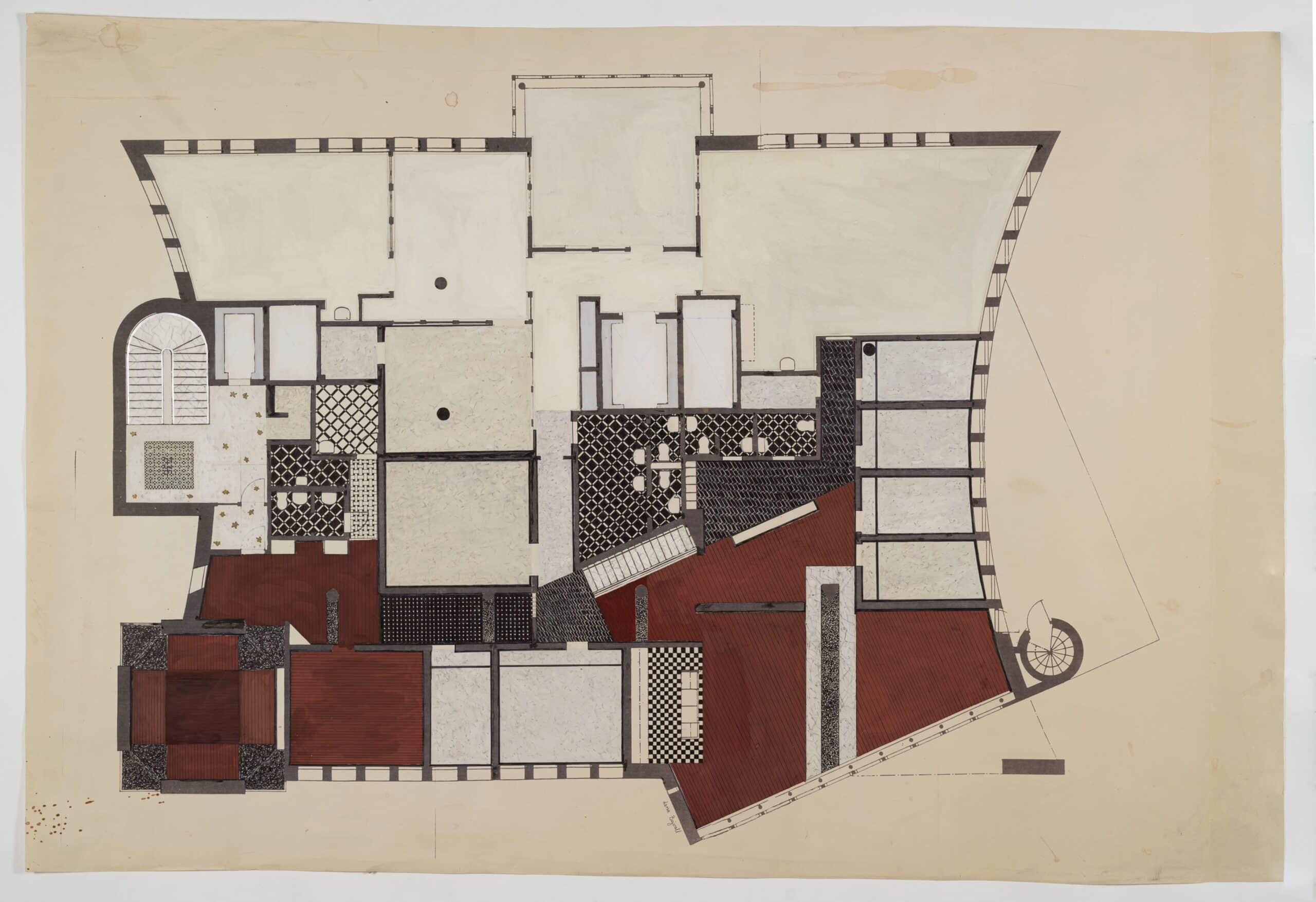

The first drawing, the first-floor plan of Örebro Riksbank, showcases a multifaceted collage with a wide variety of patterns and materials: wine-red parquet, black brick, a star-studded motif on white marble, black-and-white mosaic, chequerboard, black granite, and even unassuming parts. Within this mosaic, a smaller pattern emerges with the enigmatic equation ‘2 + 35’. Deep within the building lies a hidden world of concealed chambers—a testament to the culture of bank secrecy.

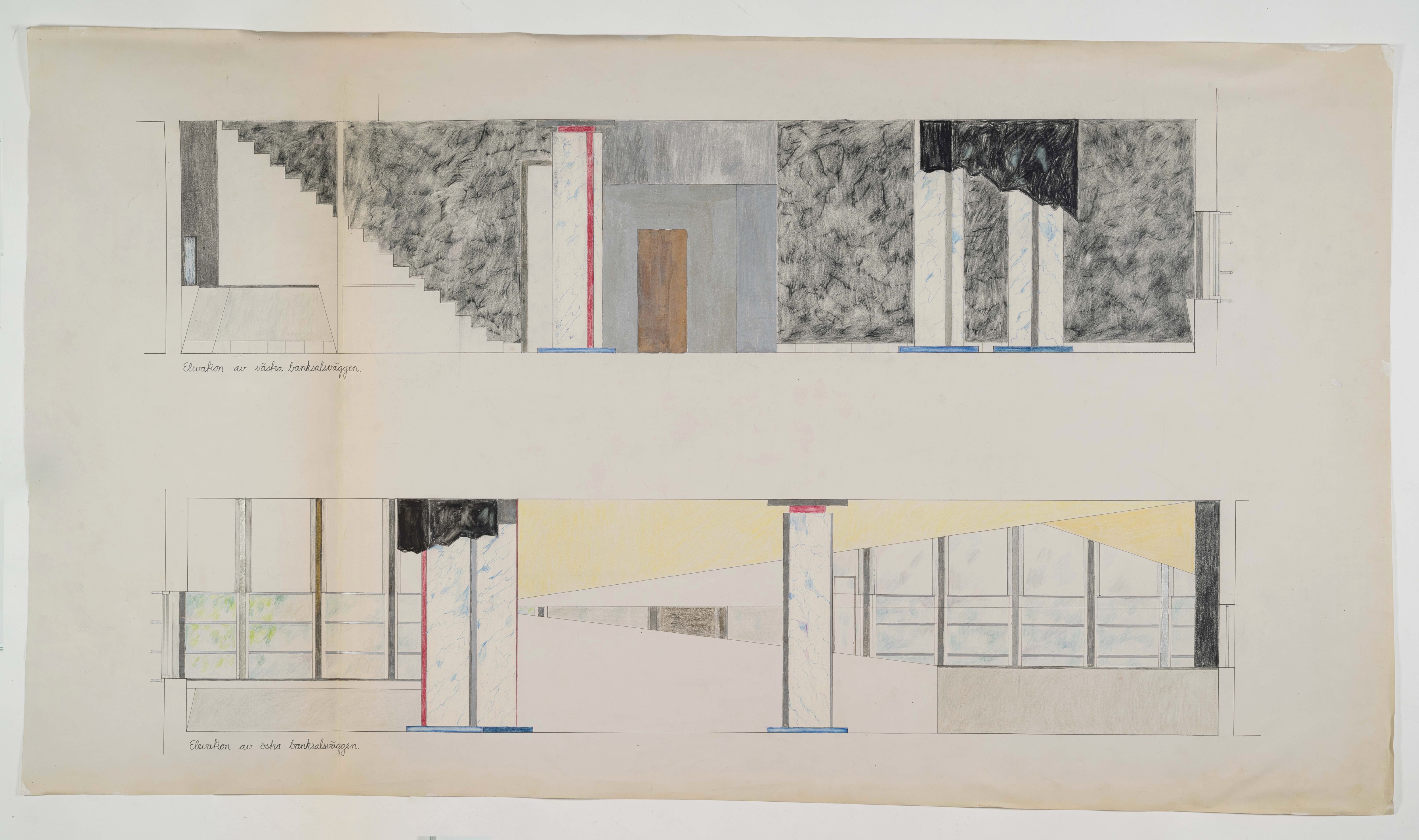

This intriguing interplay gains complexity in the west-side bank hall elevations, the second drawing of Örebro Riksbank. Confined spaces seem to appear when looking at the patterns that traverse the walls along various axes as columns emerge with shadows leaving imprints on the floor—reminiscent of those in Peter Celsing’s Villa Klockberga from 1969.

As a young architect, Henriksson began his career at Peter Celsing’s architecture firm. Following Celsing’s passing in 1974, he took on the task of completing Riksbanken in Stockholm (1976). A few years later he was assigned to design the equivalent bank building in Malmö (1978) together with Danish architect Paul Niepoort.[1] Örebro Riksbank marks Henriksson’s third project of this type in Sweden, granting him unparalleled expertise. Guided by his design visions and driven by the visual impact of surprise and wonder, our senses are stirred by the unexpected and unexplained. What is a door, a floor, a wall? What should be sought to be comprehended in a building where nothing conforms to the standard? Every column is slightly different from the next, yet they all exude a sense of uniformity, reminiscent of a figure wearing a marble-patterned suit, complemented by a red hat and a lengthy scarf, presenting additional enigmas for consideration.

A wall is covered with a render that makes it appear nearly matte, and rich in pigment. Intensely cluttered with circling lines the texture resembles a stucco lustre-covered surface, invoking a sense of mystery and history. In glaring contrast, a gleaming silver-like surface emerges, piercing the darkness, and shimmering like a treasure chest. Here, the secrets of the bank vault are revealed to the visitor, as we start to imagine the treasures concealed in these spaces. Every line is meticulously drawn in clear pencil strokes without a trace of accompanying shadows. The absence of shadows accentuates elements that step forward just as prominently. Through the presence of architectural elements such as various windows, embrasures, and staircases, we anchor ourselves in a tangible reality that forges a connection to the human scale. A conscious choice of focusing on feelings and experiences, as well as the attention to proportion, lighting, and material selection infuse life into the building.

Beyond the excesses and branding culture of the 1980s, there is something romantically enigmatic about Örebro Riksbank—this building cannot be easily deciphered. This is a departure from established principles of order and design, an exploration of complexity through diverse materials and effects. A sense of liberation, unburdened by the market’s more commercial demands.

Notes

- Paul Niepoort and Jan Henriksson, ‘The Bank of Sweden, Malmö’, Arkitektur, Vol. 79, No. 4, (May 1979), 23-27.

Felicia Liang and William Wikström are both architects and assistant curators for the Collection at ArkDes—Sweden’s national centre for architecture and design.

This text is one of the selected responses to the Open Call: Storytellers, Observed—an inquiry into the origin and circumstances of a single drawing (or series of drawings), observing the ways by which each achieves the specific purpose for which it was made. For further information click here.