W. R. Lethaby: The Church of Sancta Sophia, Constantinople

This is the third text in this series, where Hugh Strange visits key texts throughout W. R. Lethaby’s life.

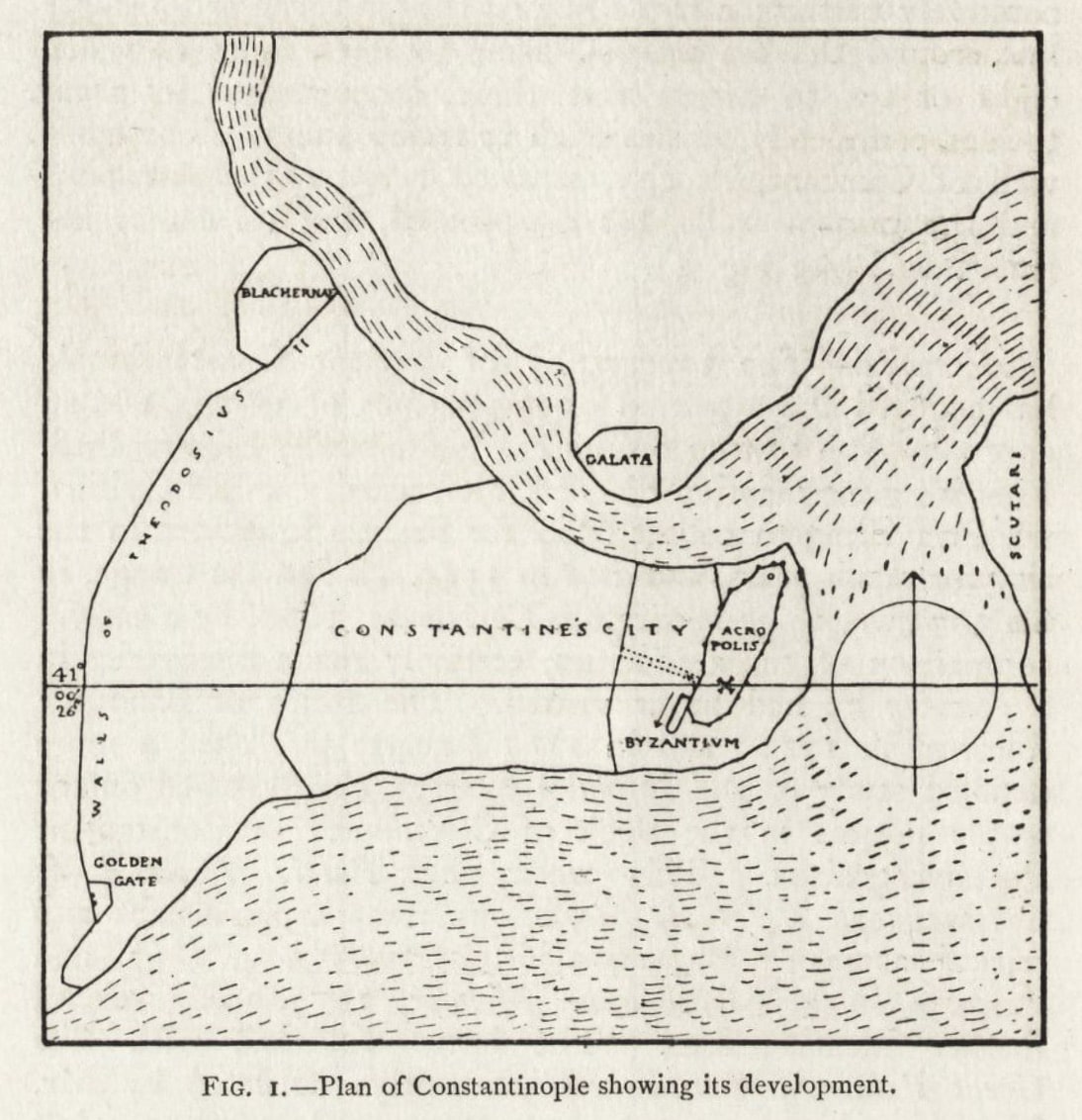

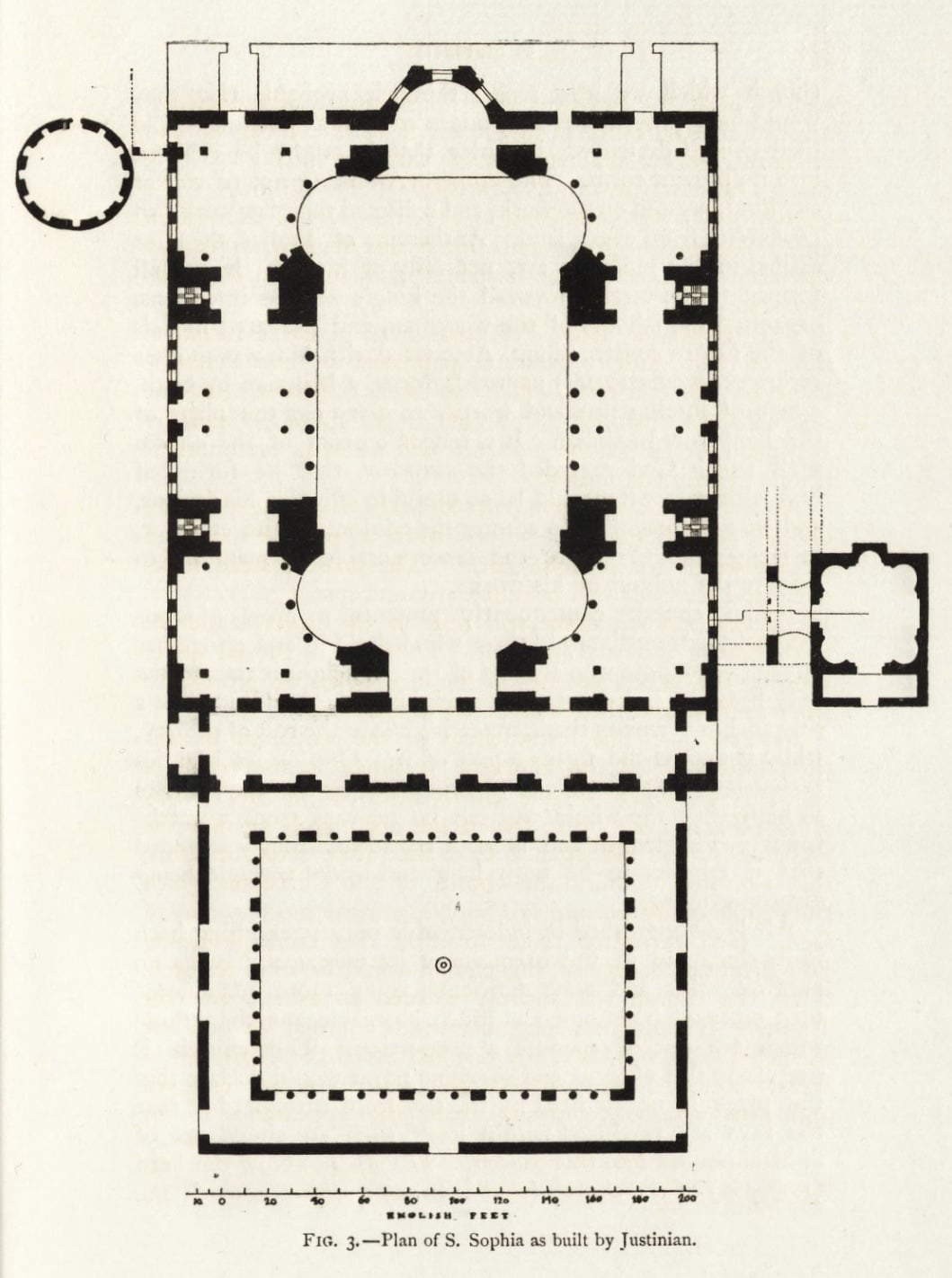

William Lethaby’s second book, The Church of Sancta Sophia, Constantinople: A Study of Byzantine Building, published in 1894, could hardly have started on its subject more emphatically, ‘Sancta Sophia is the most interesting building on the world’s surface’. Co-authored with Harold Swainson (a colleague from their time working together at Norman Shaw’s office), the publication presents a detailed appreciation of a remarkable building and, in contrast to the loosely structured quality of his first book, Architecture, Mysticism and Myth, we are presented with a clear and in-depth study of rigorous scholarship.

The book established a new direction in Lethaby’s output. He went on in the years following to publish a number of works of architectural history including Leadwork, Old and Ornamental, and for the most part English; Medieval Art from the Peace of the Church to the Eve of the Renaissance, 312-1350; and Westminster Abbey and the King’s Craftsmen. Alongside these in-depth studies was a commitment to the care of existing buildings through his significant involvement with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, and, from 1906, lasting twenty-two years, his role as Surveyor of the Fabric at Westminster Abbey.

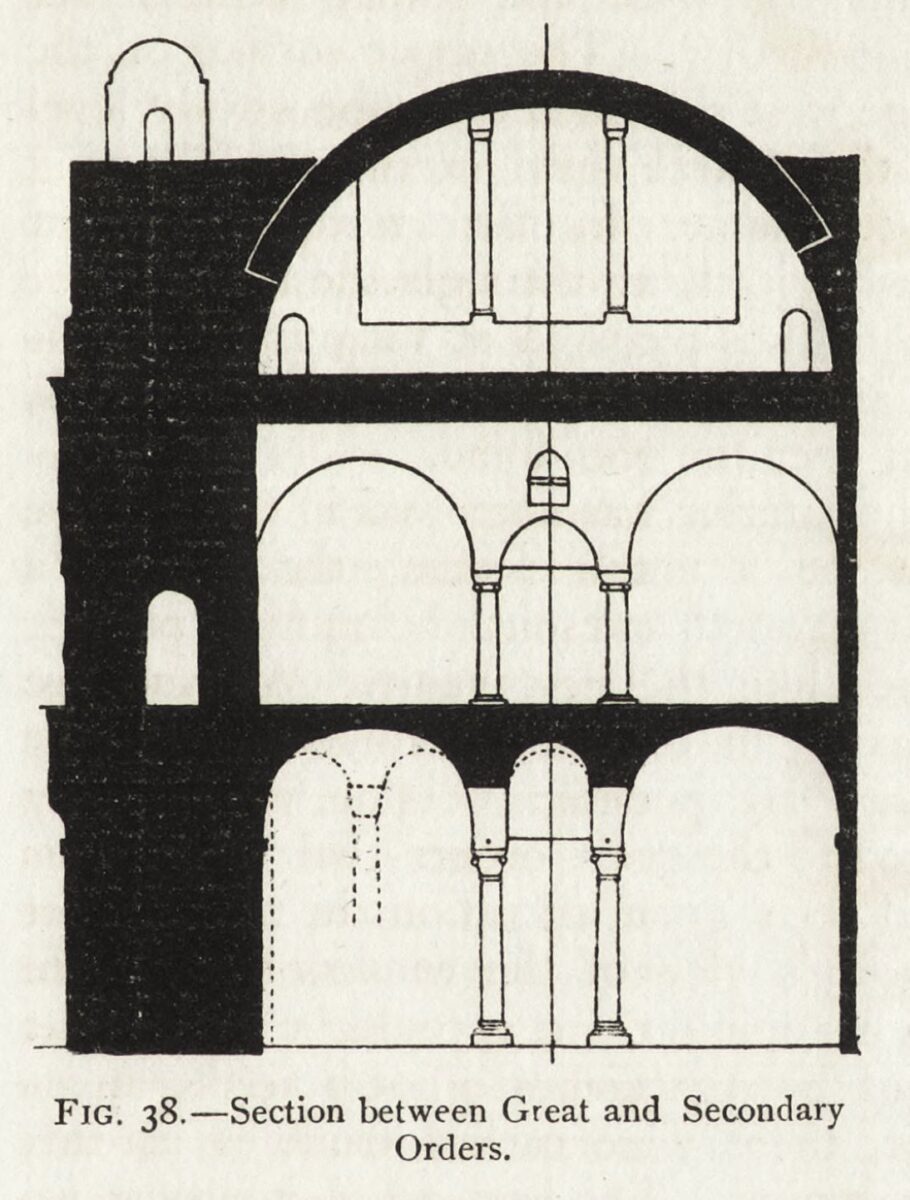

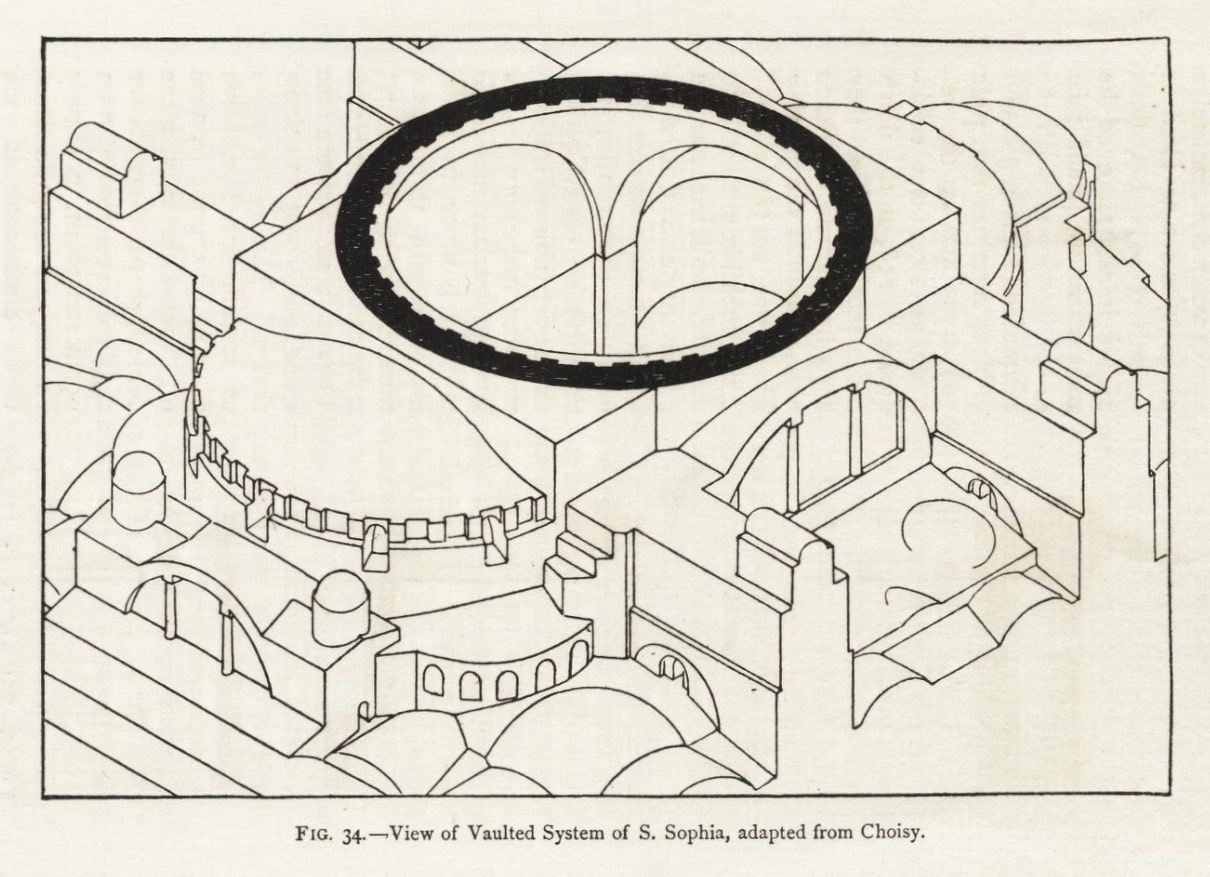

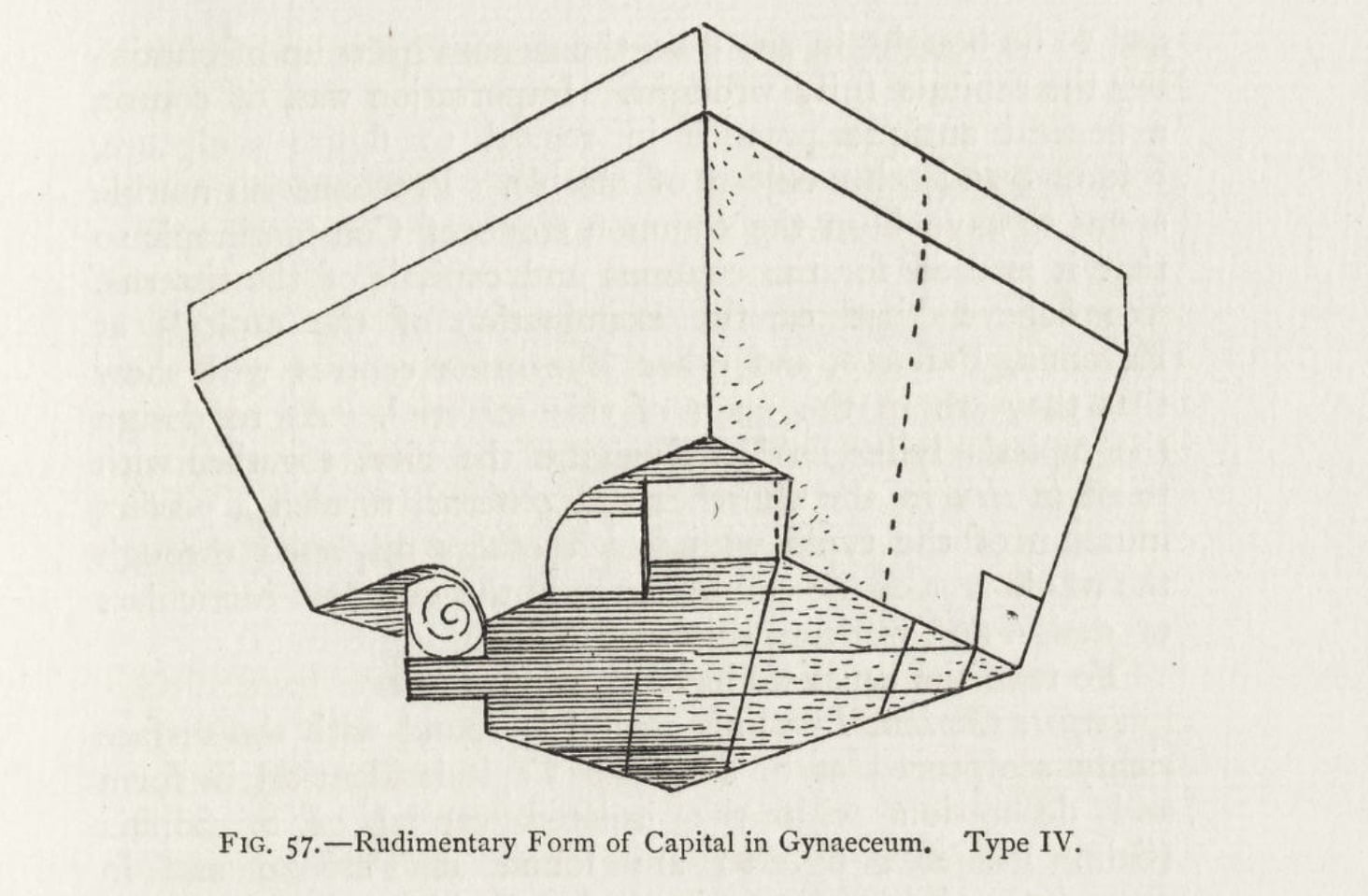

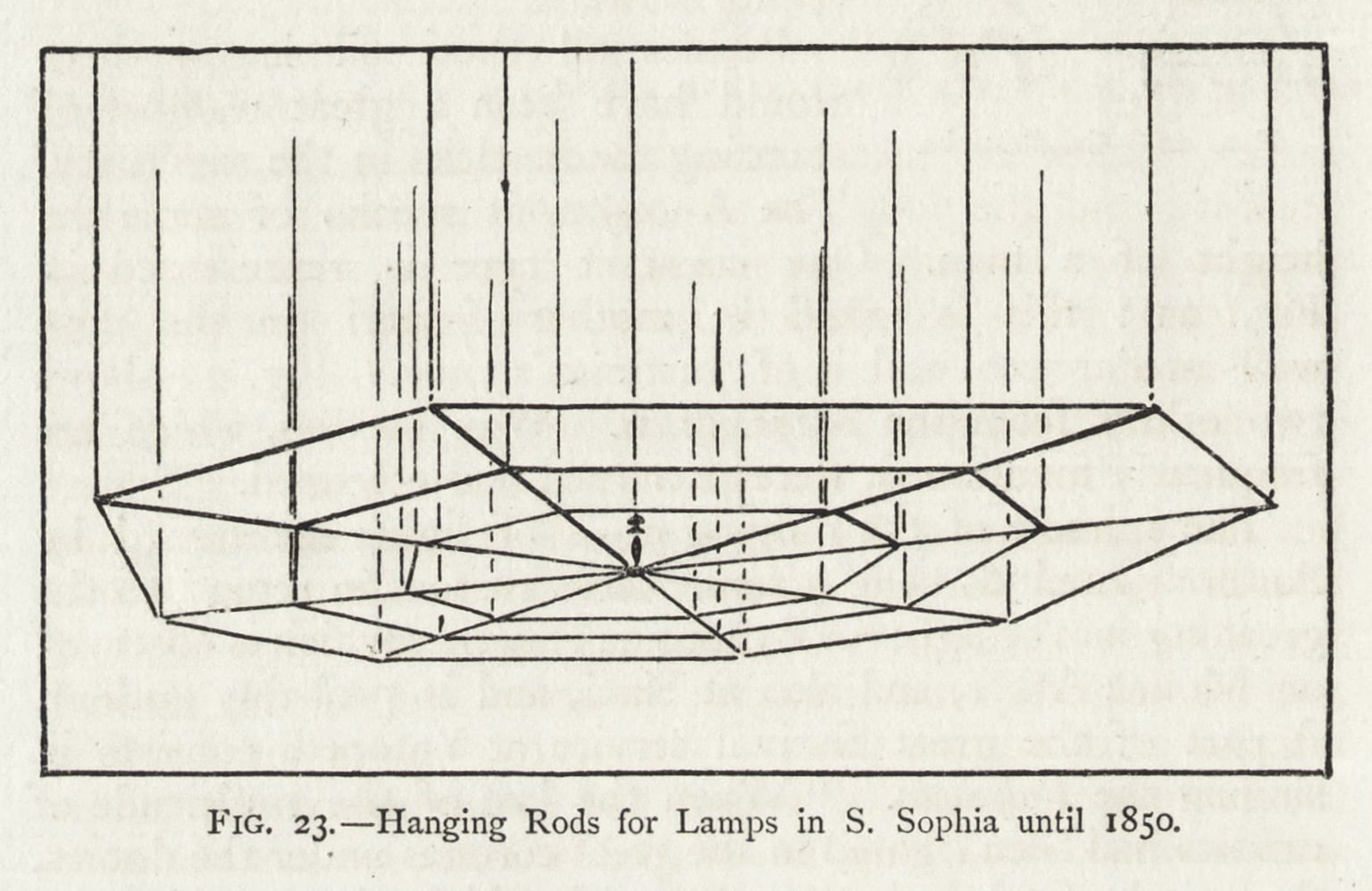

Commencing with the historical development of the church, the book reveals with care and thoroughness the building’s spatial organisation, construction and ornamentation; the text clearly illustrated by a series of line drawings by Lethaby. Throughout, the authors reveal the relationship between architectural effect, architectural history and construction, for instance, carefully describing the historical significance in the church’s architecture of the integration of arch and column, articulated through the development of a new order of column capital, ‘the problem was […] to teach the column to support the arch.’.

The authors identify as fundamental to the success of the building both the vision of the client and the structure of labour relations within the construction workforce. Of particular interest in this respect is Chapter X, ‘Building Forms and the Builders’. Having depicted the church’s spatial layout and decoration, the authors proceed to recount the roles of the master builders, Anthemius and Isodorus, together with the building’s construction techniques and sequencing, all framed within a description of the broader culture of building trade organisation. Key here is Lethaby’s interest in the Medieval guilds as a successful organisational structure, from both a political and artistic perspective. Whilst primarily a work of clear-sighted historical scholarship, the book reveals most tellingly in this chapter Lethaby’s suggestion that Sancta Sophia also offers contemporary lessons, not least in the model of the guild as a form of labour organisation free of middlemen, or ‘Contractors’.

Lethaby and Swainson produced their book at a time of renewed interest in Byzantine architecture, and by accounts, it played a significant part in the developing movement. John Bentley’s Westminster Cathedral, London’s primary example of this tendency, was designed in the Byzantine style almost immediately after the book’s publication, and Bentley apparently took the text with him on a study tour after receiving the commission. But stylistic revisionism was furthest from Lethaby’s intentions in producing his book. Rather, through the whole-hearted appreciation of ancient buildings he saw the foundation for a better way forward, articulated within the book’s preface, ‘A conviction of the necessity for finding the root of architecture once again in sound common-sense building and pleasurable craftsmanship remains as the final result of our study of S. Sophia.’

The Church of Sancta Sophia, Constantinople: A Study of Byzantine Building by W. R. Lethaby can be read online here. For more writings by Hugh Strange, click here.

– Hugh Strange