Watchful Solitude: John Hejduk and Venice

The Thirteen Watchtowers of Cannaregio (with Waiting House) and House for the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate were conceived as an urban ensemble and laid the foundation for the later phase of John Hejduk’s work, which he described as an ‘architecture of pessimism’, and encompasses his best-known projects, such as Victims, Berlin Masque, Soundings and Vladivostok.[1] The Cannaregio projects mark an intermediate point between the origin and destination of Hejduk’s architecture. The Thirteen Watchtowers of Cannaregio (with Waiting House) and House for the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate relate by temporal continuity. Their physical and geographic linkages—the specific distances and locations in the context of the city—are less important than a sequential programmatic interdependence. We may refer to this system as a ‘narrative programme’ that operates simultaneously at urban and individual dimensions. The themes of individuality, loss, absence, death, abandonment, and exclusion are intertwined with their collective pairs: private property, social life, cultural norms, hierarchies, and modes of production. The interweaving of public and private functions—watching, waiting, and transiting—is triggered both within buildings and out in the city. The Cannaregio projects build a critique of individuality through gradients of retreat from the collective environment. The relationship between private property and citizenship appears at the centre of Hejduk’s concerns.

Hejduk’s work in Venice was developed in the 1970s while a theoretical reform in the discipline of architecture was taking place.[2] Michael Hays describes this period as a linguistic inquiry, which unfolded as ‘the attempt not only to codify architecture as a language but, further, to collapse the distinction between the object of architecture and the theoretical text.’[3] According to Hays, pessimism for Hejduk appears as a critical task, not as an end in itself; it is a resource to propel thinking forward or with a change of direction. Through figures of angels, a ‘negative restoration’, or reconstruction, is enhanced.[4] In the project at Lake Baikal, within the later phase of Hejduk’s production, Hays describes angels that rehearse states of becoming something else while most of us are occupied with what we already are.[5] This discontent with the present is what characterizes Hejduk’s pessimistic architecture. In it, programmatic narratives, characters, and types gain more prominence. They can be seen as poetic tools in response to the eclipse of criticism that marked the second half of the twentieth century.

Hejduk describes the end of the ‘age of optimism’ as marked by the transformation of functional categories in architecture and a distancing from the ‘optimistic programmes’ of the modern era. According to the architect, when doctors cured tuberculosis, they deprived modern architecture of one of its best programmes.[6] When organizing his projects carried out between 1947 and 1954 in Mask of Medusa, he notes that certain recurring elements appeared, particularly with respect to the nature of the programmes, or to what the character of the programmes revealed. Chapels, cathedrals, cemeteries, bridges, ski lodges, municipal fairs, biology centres and zoos represented aspects of a time that were tied to religious and recreational structures related to the end of World War II.[7] The house, as an individual unit, becomes increasingly relevant and the possibility of developing ‘pessimistic programmes’ is a consequence of a collective psychic state in the search for social balance. We may understand the pair optimism and pessimism in Hejduk by the opposition between utopia and realism. This argument is aligned with the theoretical discourses prevailing in his time, which culminate in Manfredo Tafuri’s text Architecture and Utopia.[8] This pessimistic approach leads Hejduk away from the single-family home programme towards a more radical agenda: the masks.

The Cannaregio Projects in Venice are situated precisely before this most radical turn. They vibrate between the two propositions, at the centre of the realism-utopia counterpoint. Hejduk’s ‘pessimistic architecture’, of masks and angels, is often marginalized as an architectural construct. It is commonly understood as a disengaged artistic project. Another perspective may position the formal radicalism of Hejduk’s urban and architectural universes as a radical critique, in which a socio-political dimension is even more profoundly present. Through its fragmentation, or its amplification in malleable geometric expressions, Hejduk intensifies the critical project of architecture.

A common reading of Hejduk’s work points to a departure from practice towards theory.[9] In Five Architects, Philip Johnson describes Hejduk as a theoretician-designer. The 1992 exhibition Outside Practice in Chicago served to reiterate this vision. Five Architects served paradoxically to flatten the interpretation of Hejduk’s work; by positioning it alongside other architectures of New York City, the publication revealed some common characteristics, but hid divergences that are significant. The perhaps best-known publication of Hejduk’s work is also the most controversial.[10] Stan Allen refers to this reading of the architect’s work as the result of a confusion about the projective exercise: the speculative and hypothetical dimensions of Hejduk’s work were confused with theory per se. In contrast, Allen suggests the opposite: no theory survives in Hejduk’s work, only architecture itself. Hejduk does not present abstract thoughts about drawing, language, narration, or edification, but rather drawings, languages, narrations, and buildings per se. Allen describes this position as a form of resistance to theory, an approach that is not anti-intellectual or apathetic to the construction of thought in architecture, but one that allows for the conception of each iteration to emerge directly from within a flux of history. Individual creation then can be seen as collective accumulation and may achieve a greater disciplinary amplitude.

In this aspect, it is possible to think of architecture as a communicative art that operates in the contemporary public sphere.[11] Hejduk’s projective practice is an alternative path, distinct from Colin Rowe’s and Robert Venturi’s, as well as Peter Eisenman’s language. Unlike Eisenman, Hejduk does not explore a language ‘codified’ in architecture, but ‘evokes the disastrous potential of writing in architecture, its aspects of materiality and contingency, and its undecided making both as a toxin and as a cure.’[12] This displacement of syntax to action (from grammar to performance) is presented by Robert Somol as the Hejdukian mutation of post-war American formalism accompanied by other movements: from the plan to elevation, from geometry to narrative, from the proportional to the anomalous model. According to Allen, Eisenman’s architecture acts as the record of complicated abstractions and formal procedures, while in Hejduk’s work form is the result of a series of simple and direct manipulations from concrete elements. In Mask of Medusa, Hejduk refers to art and architecture without distinction: the arts are ‘the embodiment of specific plastic viewpoints.’[13] Through the juxtaposition of basic relationships established from a vocabulary of point, line, and volume, the possibility of an argumentation is set. Hejduk’s work from the 1970s subverts the opposition between theory and practice through the ‘collapse of the discursive privilege of language within the project.’[14] This means that, instead of separating text and design, in a descriptive conventional relationship, Hejduk incorporates the written word as constitutive of architectural form.

Although theory and practice were at first continuous in architecture, academic institutions and offices in the United States gradually diverged in the second half of the twentieth century. There was a high degree of specialization, which resulted in the separation between intellectual work and professional practice, even generating opposition between theorists and designers. This effect on our discipline contributed to the distancing from critical thinking of its ‘direct and formative’ relationship with professional practice. Theory failed to be propositional.[15] Early modern paradigms shifted in the 1970s and served to reveal the ideological power of theoretical constructs in architecture, constantly enhanced by manifestos, didactic exhibitions, and pedagogical programmes. In the post-war period, the theoretical bases of modernism, fixed in a set of guidelines and codes of professional practice, appeared to be obsolete. The connection between domains of practice and theory then reappeared as a problem. Allen suggests that Hejduk questions the unsatisfactory foundations of traditional modernism in the search for a new system out of its own practice—one that provokes and exceeds theoretical description: ‘Hejduk restrategizes the conventional use of theory understood as legitimation from outside (an appeal to that which art lacks) by systematizing practice from within.’[16] Hejduk acknowledges that in his time architecture was exhaustively theorized and affirms the impossibility of dissociating thought and practice in architecture. According to Allen, the speculative and practical, dissociated in modernism and classical tradition, are productively collapsed in Hejduk’s work.[17]

Hejduk’s proposal for Cannaregio was presented in 1978 at the Seminario Internazionale di Progettazione Architettonica, organized by the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia and the Assesorato alla Cultura Del Comunedi Venezia. A design workshop titled ‘Venezia: la sua presenza e la sua negazione’ was organized in order to investigate scenarios of transformation for the western region of the Cannaregio district. The seminar gave rise to the exhibition 10 Immagini per Venezia, curated by Francesco Dal Co. The works of Raimund Abraham, Carlo Aymonino, Peter Eisenman, John Hejduk, Bernard Hoesli, Giuseppina Marcialis and Gianugo Polesello (in co-authorship),[18] Rafael Moneo, and Valeriano Pastor were exhibited and published. The conciliation between a historical vision of the city of Venice, almost mythical in its ever-changing uniqueness, and the violent processes of urban transformation during the second half of the twentieth century appears in the 1970s as a paradox. The city of Venice in the European context is seen as a model of resistance to modern transformations. Dal Co highlights a crisis of design tools, which seemed to be ‘hibernated’ and ‘mythologized’. In his view, the fundamental questions that modern architecture couldn’t solve had been removed ‘in an elegant critical pirouette’ to make way for the postmodern. The meaning of the discipline had been affected by the weakening of practices, techniques, and rationalities, resulting in the detachment of architectural thought from the professional environment.[19] 10 Immagini per Venezia was one of the first in a series of studies for the western region of Cannaregio, the area adjacent to the Santa Lucia train station. It was considered peripheral, given its distance from the historic centre. The initiative sought to expand paradigms of intervention in the city through a renewed imaginary, capable of reinventing its image beyond the reiteration of its existing urban fabric.

Along with drawings, Hejduk presented the following texts:

The Thirteen Watchtowers of Cannaregio

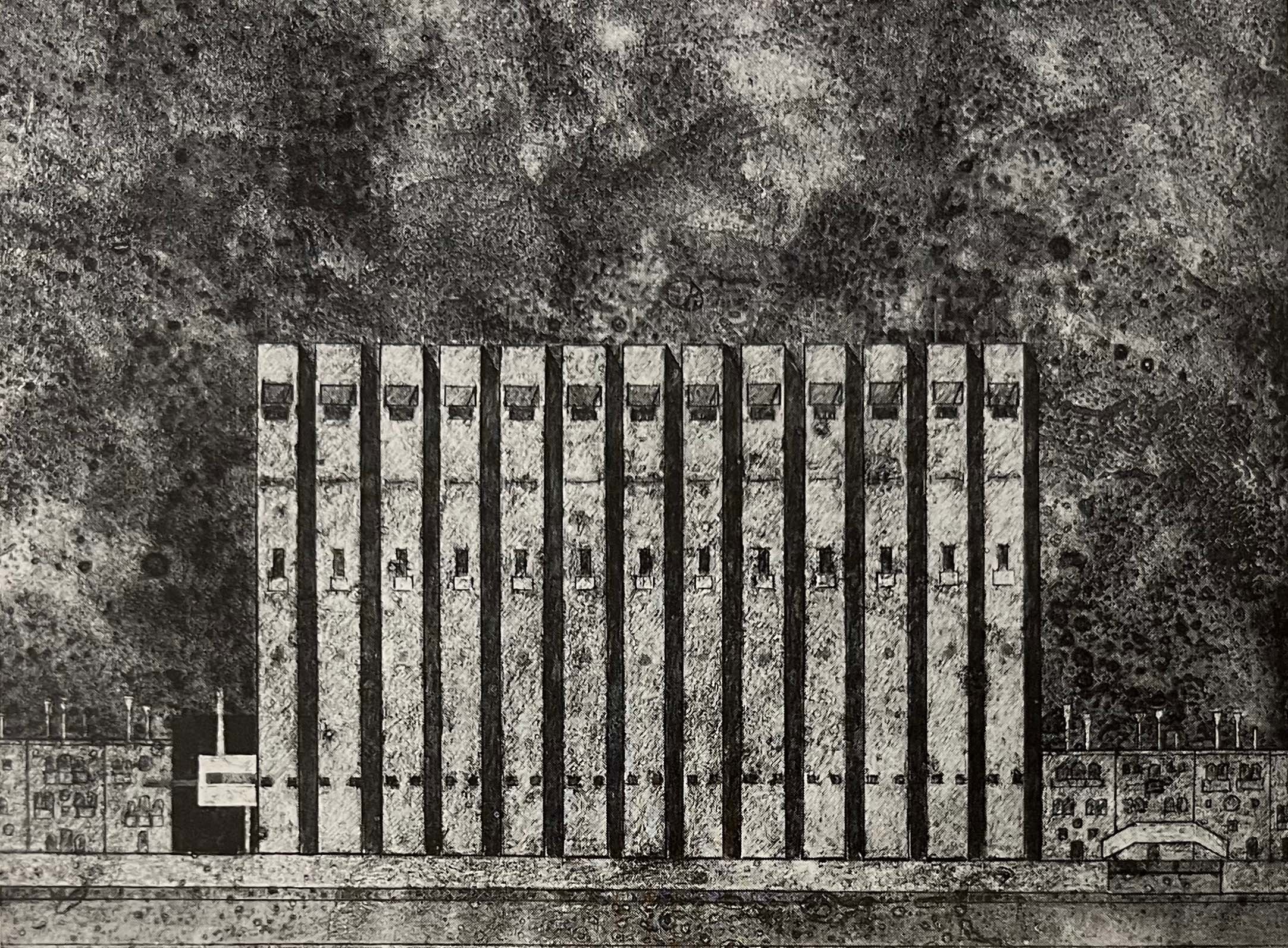

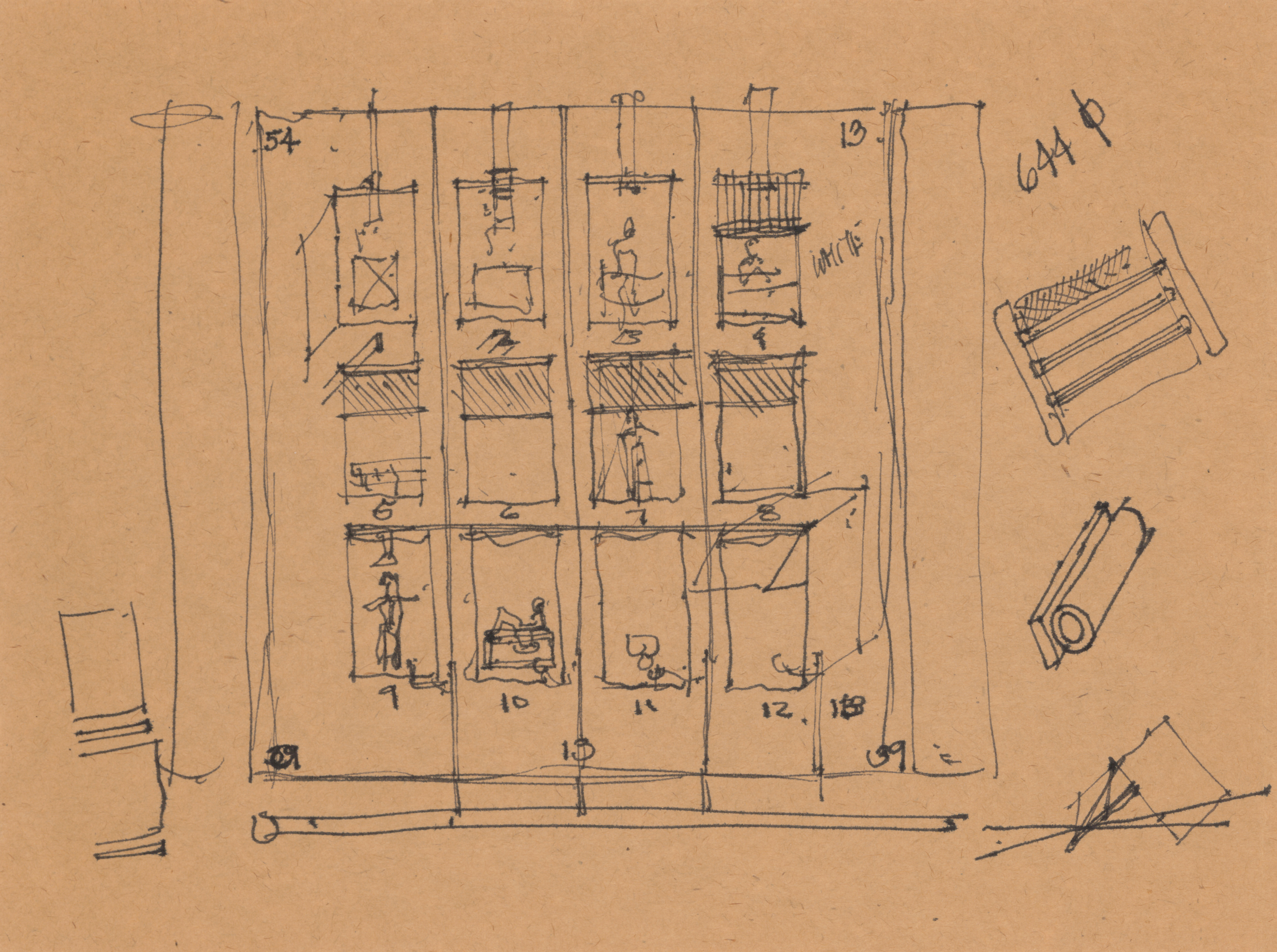

Thirteen towers placed in a row four feet apart. Each tower measures 16’ x 16’ x 96’ high. They are constructed of reinforced-concrete masonry and a cement-stucco finish. The exterior color is basically a Venetian pink, green, grey, and white. The doors and shutters are made of wood slatting; metal parts are grey. The window awnings are made of a green cloth. / The structures’ interior walls are of cement. Eleven of the towers are painted grey inside; one of the towers is painted black inside; one of the towers is painted white inside. / […] / The city of Venice selects thirteen men, one for each tower for life-long residency. One man lives in one tower and only he is permitted to inhabit and enter this tower. A fourteenth man is selected to inhabit the small house located in the campo. / Each of the thirteen tower men is pledged not to reveal his interior coloration. / The 16’x 3’ table is placed in front of the campo house and then each day is moved and placed in front of a following tower; when a cycle is completed another cycle is put into motion. / Upon the death of one of the tower inhabitants, the man in the campo house takes his place and another is selected to inhabit the campo house. / There are two bridges: one a drawbridge made of wood, the other a bridge made of stone. / The campo is large to begin with. One thousand nineteen hundred and seventy-nine 3’x 6’ stone slabs will be placed in the campo which underlooks the Thirteen Watchtowers of Cannaregio; with the passing of each year another stone slab will be added.

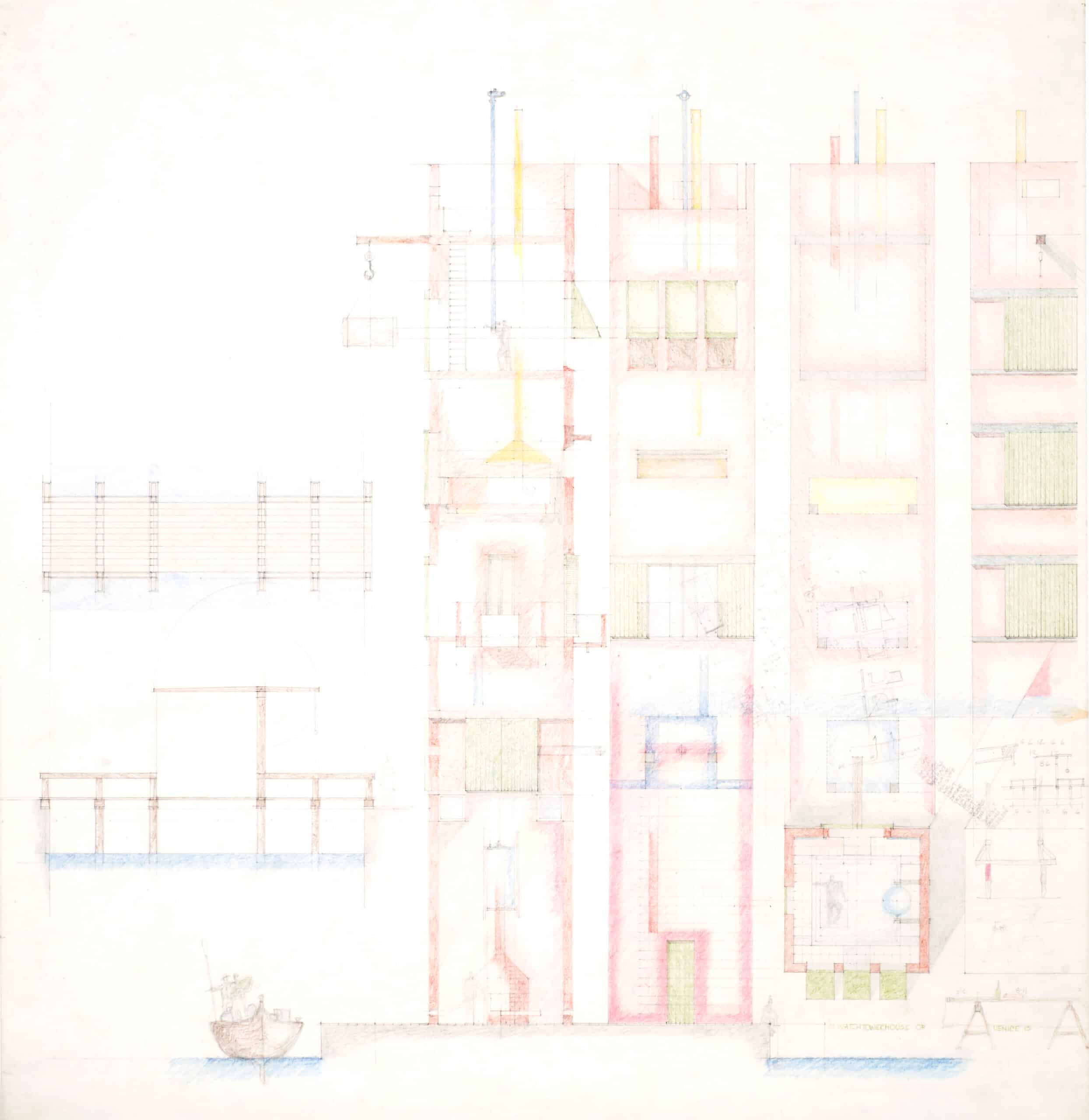

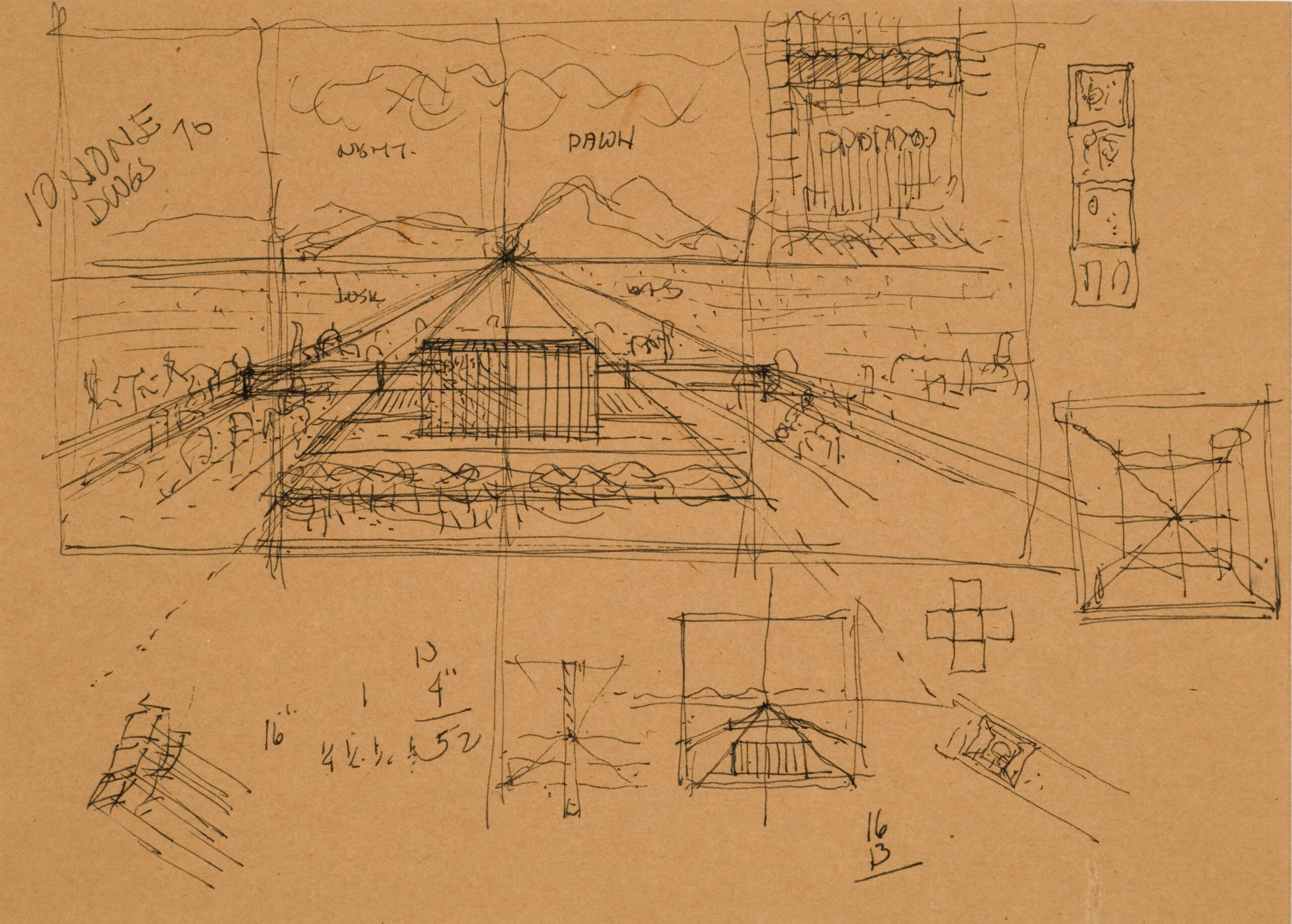

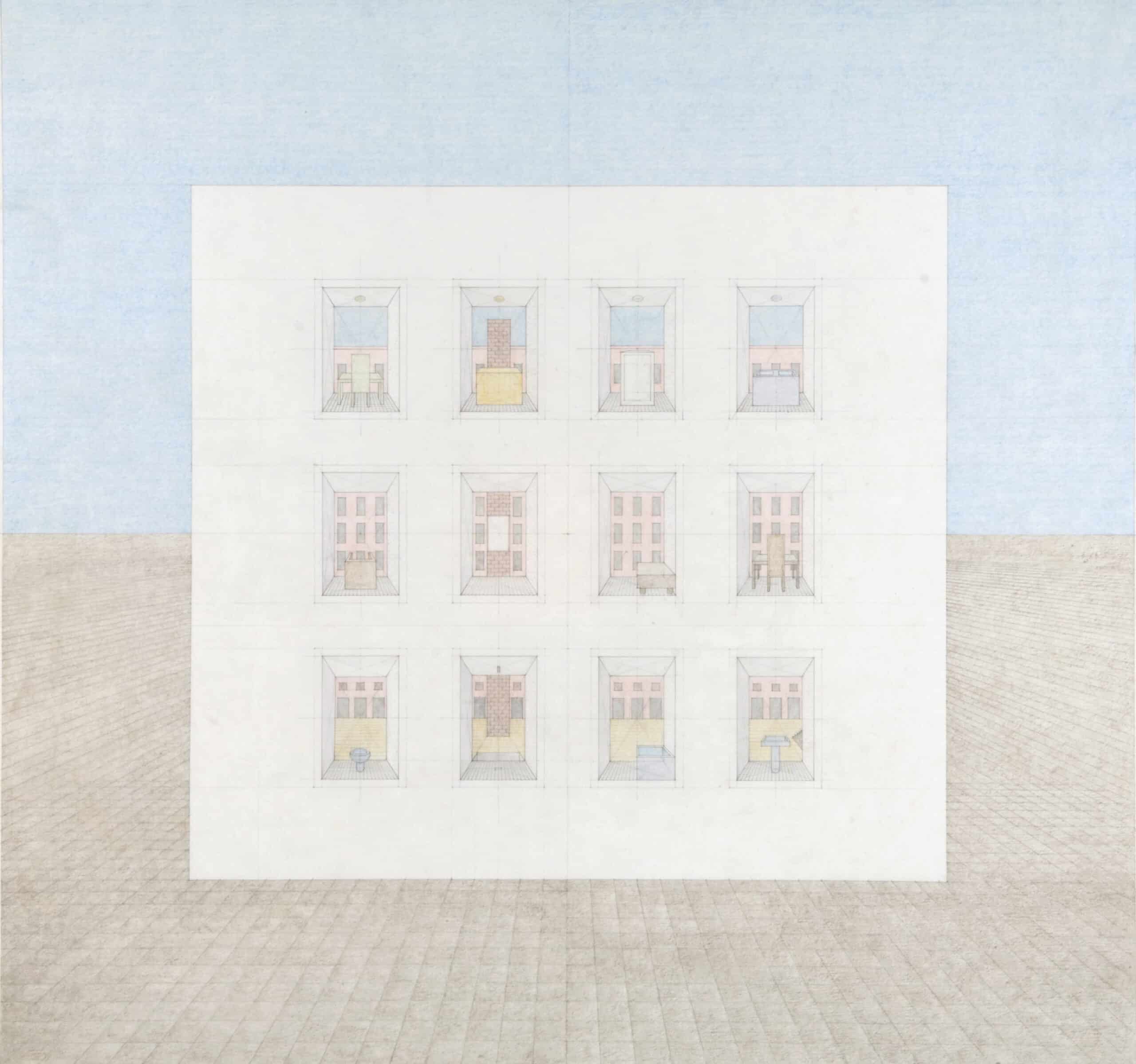

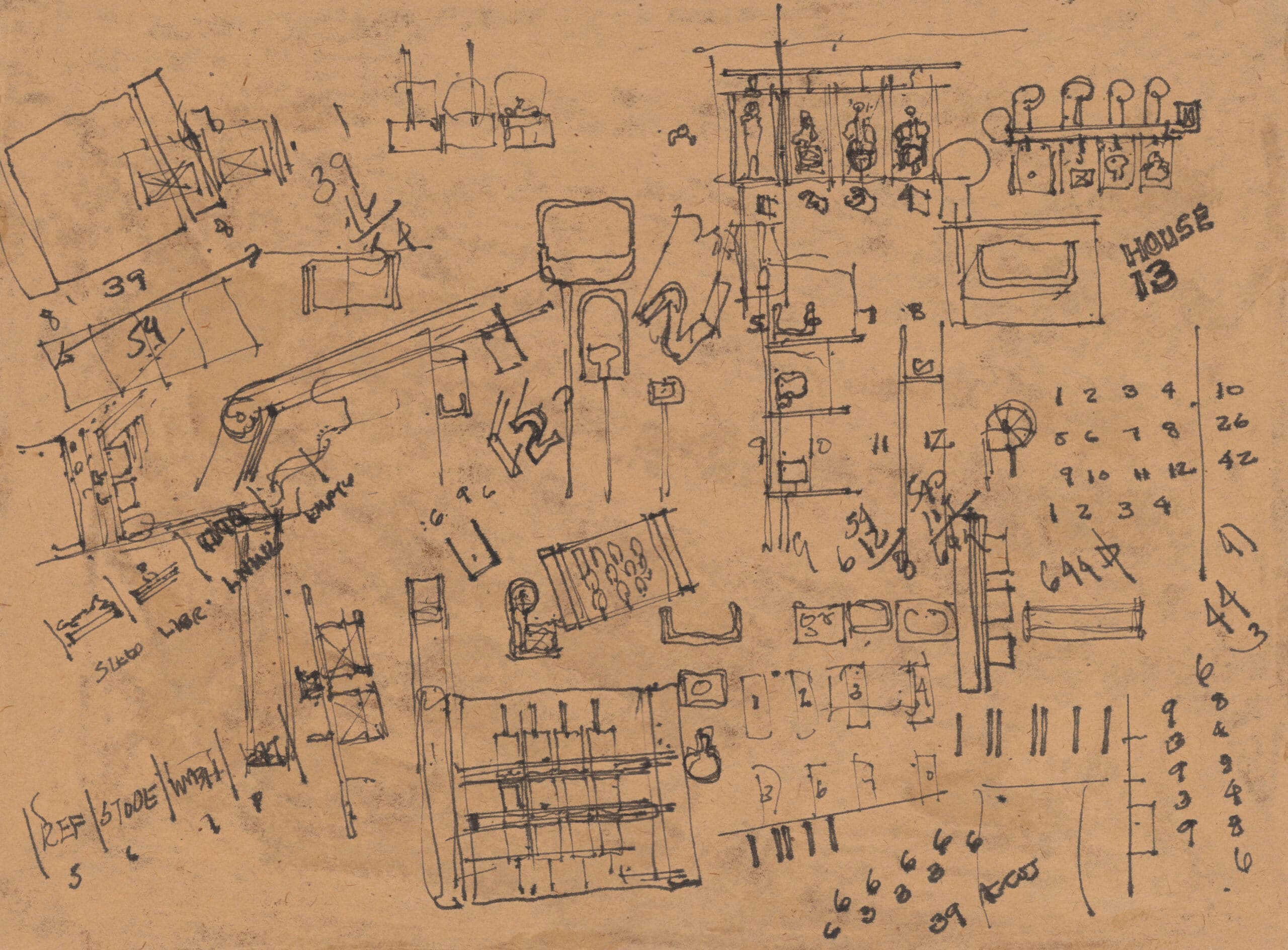

The House for The Inhabitant Who Refused To Participate

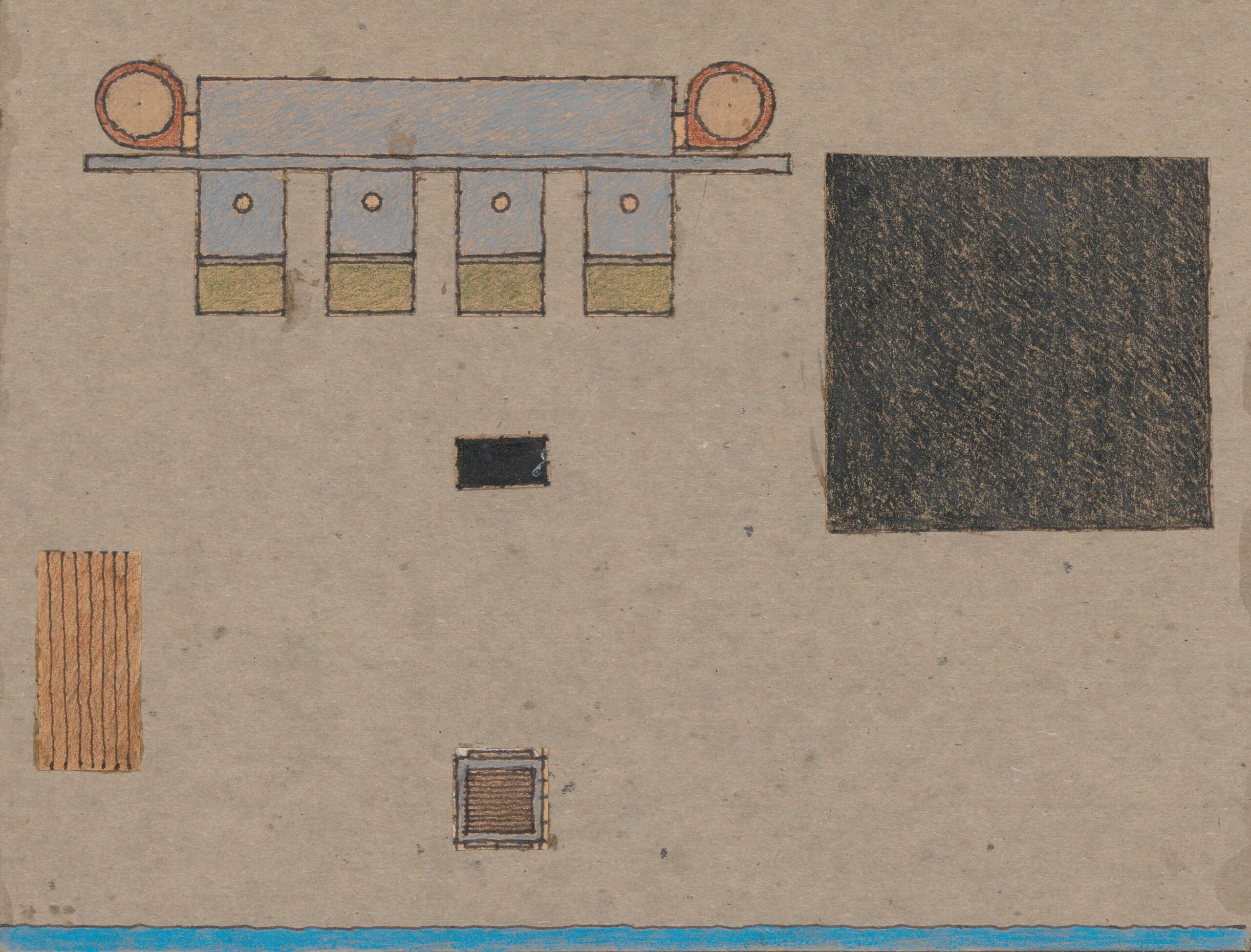

Somewhere in another part of the city overlooking some other campo there is a house inhabited by one who refused to participate. In that campo stands a 6’ x 6’ x 72’ stone tower. / The lone inhabitant’s house consists of 12 separate units. Each unit measures 6’ x 6’ x 9’. The units are suspended off a wall. / Under each unit is a number 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc. The wall itself is the 13th unit. / Unit 1 contains a kitchen sink / Unit 2 contains a kitchen stove / Unit 3 contains a dining table and chair / Unit 4 contains a refrigerator / Unit 5 contains a sleeping bed / Unit 6 contains a study table and chair / Unit 7 is empty / Unit 8 contains a living seat / Unit 9 contains a bath sink / Unit 10 contains a bathtub / Unit 11 contains a shower / Unit 12 contains a toilet / At the exact level of the Participant of Refusal’s empty cell there is affixed upon the campo tower a mirror, the precise elevation size of the opposite cell. When the inhabitant of the house stands in his empty room he simply reflects himself upon the mirror of the opposite tower. / Any citizen is permitted to climb the ladder and enter the stone tower. Once in the tower the citizen can see the lone inhabitant across the campo within his cell. The citizen can observe without being observed. / There is only one risk for the hidden observer. Another citizen may release the overhead tower door consequently enclosing within the tower the citizen observer. / Between house and tower within the horizontal plane of the campo is cut out a 3’ wide, 6’ long and 6’ deep hole. [20]

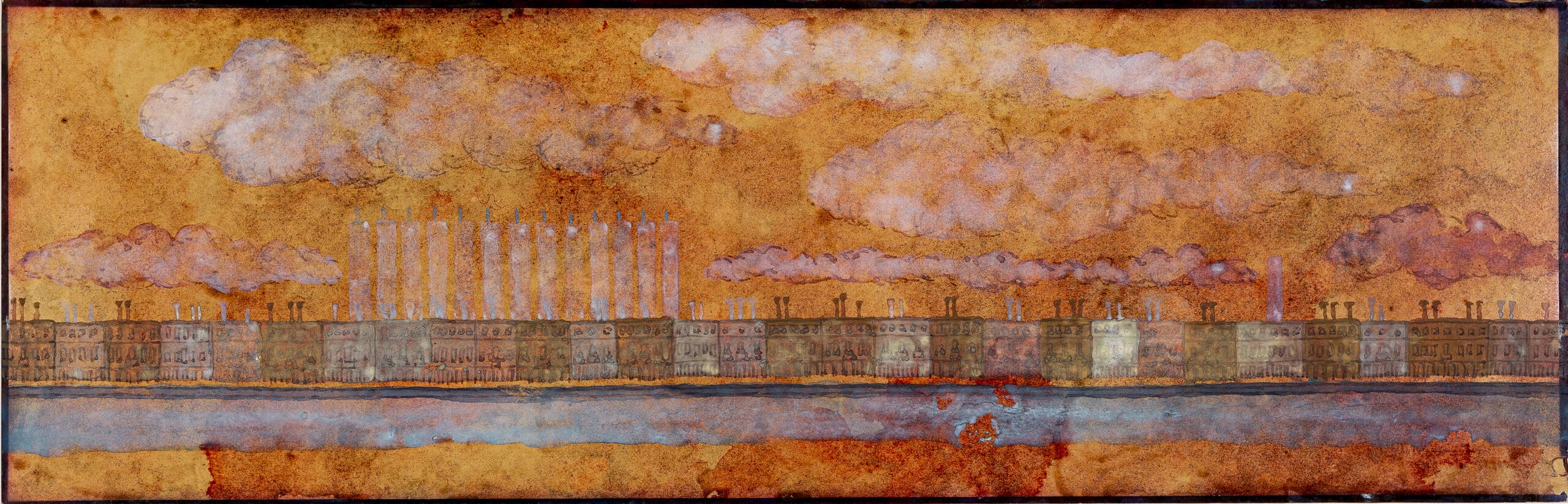

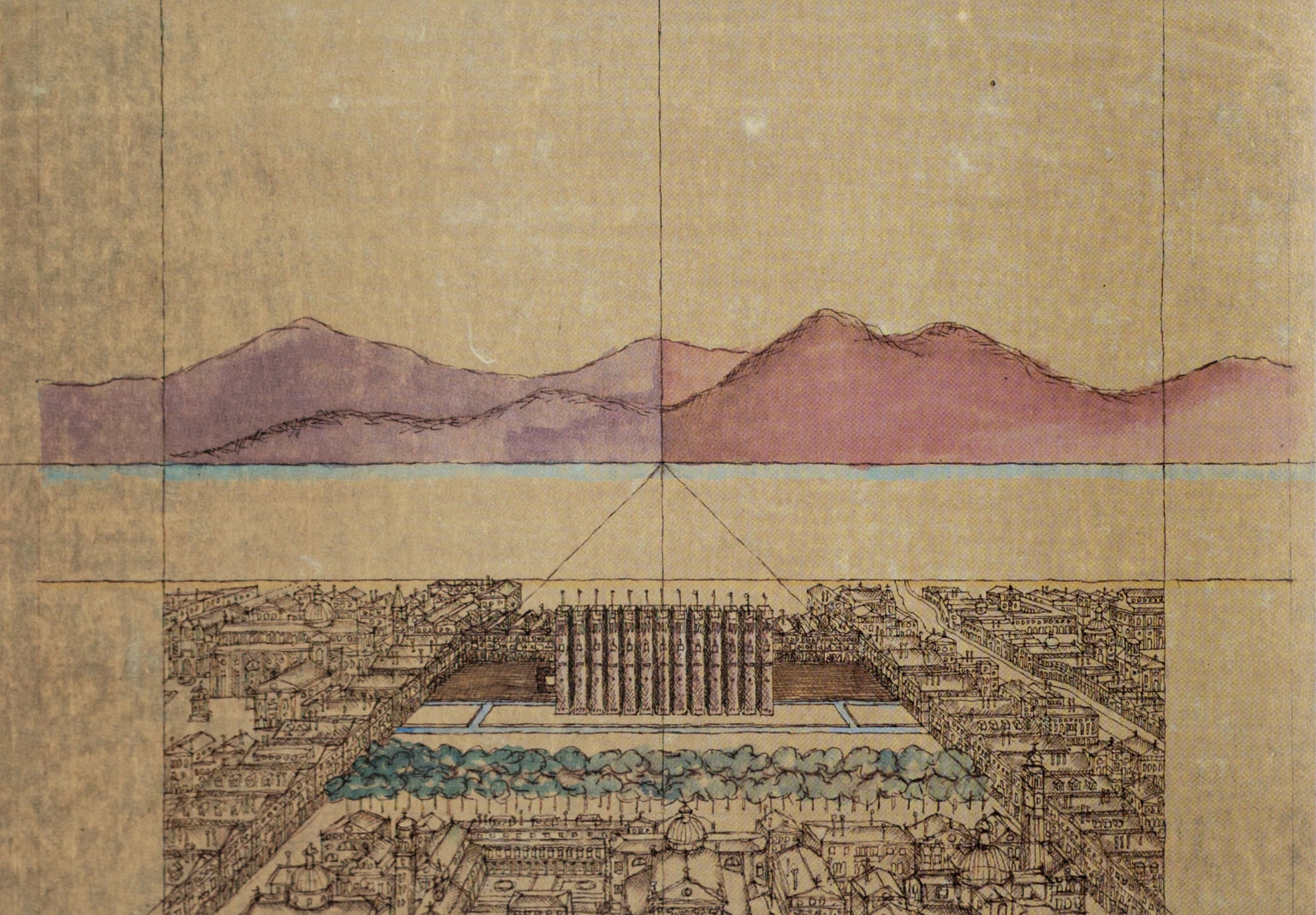

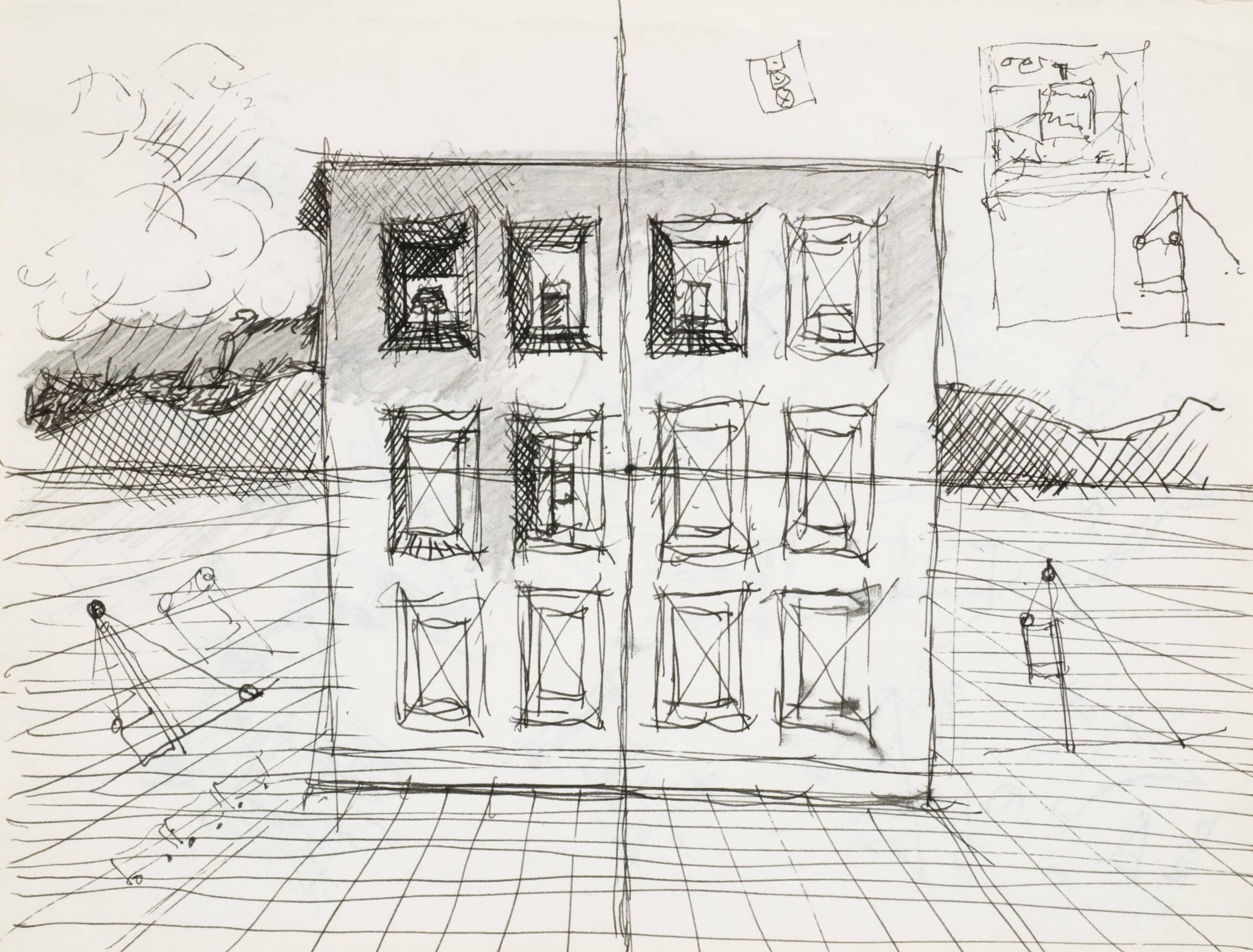

A scenic narrative in a fictional place is bounded by an abstract, sharply orthogonal historic city. From an aerial perspective, the city of Venice is a universal place, organized by a series of layers: monument (historic city), countryside (vegetation), a plain interrupted by a canal, the Towers, another canal, the Waiting House, and the continuous urban fabric that ends on the horizon framed by topography. At the top of the towers is an observation deck, where the inhabitant engages with an expansive view of the city. There is a mirror-like relationship between the towers and the geographic scale of Venice: the towers are both observant and observed. Michael Sorkin describes the individual experience in the tower as ‘monumental, watchful solitude’, around which an interplay of wakefulness, isolation, occlusion, and amplitude occurs.[21] The Waiting House near the observation towers is dedicated to sheltering a citizen who awaits the death of one of its inhabitants to then take his place. The idea of anticipation is marked by the permanent presence of the house of the citizen in waiting. Elsewhere in the city, Hejduk proposes The House for the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate. It is dedicated to a citizen who denies the narrative programme of the towers. The house simultaneously emphasizes exclusion and autonomy through its compact and independent geometries.

In Hejduk’s proposal, an overlay of scales is employed: the towers, the historic city, and objects. There is a desire for horizontality in representation: the ground line is horizontally continuous, but a geological (temporal) layering is suggested in the vertical direction. In the aerial perspective (published in Mask of Medusa, but not included in the exhibition catalogue), Hejduk abstracts the specificities of the site, highlighting a natural horizon—an almost fictional landscape appears more prominent than the city itself. In the proposal, he does not define a clear insertion in plan. On the contrary, his narrative keeps it open. It is not possible to understand where precisely each element would be placed—‘Somewhere in another part of the city overlooking some other field there is a house inhabited by one who refused to participate’.[22] What is established by the author accurately are the relationships of proximity and distance between the elements, arranged in a dialogue with the city. Characters are both fixed and mutable. Context can be apprehended as the background and originator of new events and new realities. Specific site coordinates become secondary to the experience of exchange among the city, architectural form, and inhabitants. Hejduk frequently describes the way in which architecture responds to site through universal socio-spatial conditions, focusing on architecture’s ability to affect the spirit.

What is important is that there is an ambience or an atmosphere that can be extracted in drawing that will give the same sensory aspect as being there, like going into the church and being overwhelmed by the Stations of the Cross (a set of plaques which exude the sense of a profound situation). You can exude the sense of a situation by drawing, by model or by good form. None is more exclusive than the other or more correct. They are.[23]

For Hejduk, urban planning visions are utopias based on an ideal of permanence and are doomed to obsolescence. Alternatively, he proposes the creation of non-static realities, such as radical nomadic objects, which generate ambiguities in the traditional object-context relationship. This urban language is most legible in his projects in Berlin and Victims. Buildings are dispersed throughout the city. According to Laís Bronstein, Hejduk adopts a critical position to the classical notion of unity through an anti-Cartesian view of the body. He replaces unity with fragmentation in the process of transposition of the architectural object to the urban scale. According to Bronstein, while Rowe used the fragment to assemble, Hejduk used it to disassemble.[24] This conformation of a world within another world is the proposition of a reality that is defined at the same time from what it invents and from what it denies and excludes. The construction of a new cosmos for the contemporary man is at the heart of Hejduk’s work in Venice. Buildings relate through their agendas of inhabitation, as interdependent temporal and existential conditions of waiting, death, refusal, and denial. In Venice, the architect rehearses the programmatic dispersion that is intensified and becomes more legible in a later phase of his work.

The towers are positioned on an island: they rest on a ground that is separate from the city by canals, and they are also separate from each other. The separation between each of the towers does not compromise the planar reading of the composition in the city landscape. Through the discontinuity between the existing buildings and the new intervention (as isolated objects), it is almost autonomous. The compact and minimal programme of each floor seems to eliminate what could be considered excessive. The compact volumetric and planar compression of the group of towers carries a geometric language similar to the Wall Houses. This language, characteristic of Hejduk’s preceding projects, is later developed in his mask projects, when it takes on a different, more radical expression.

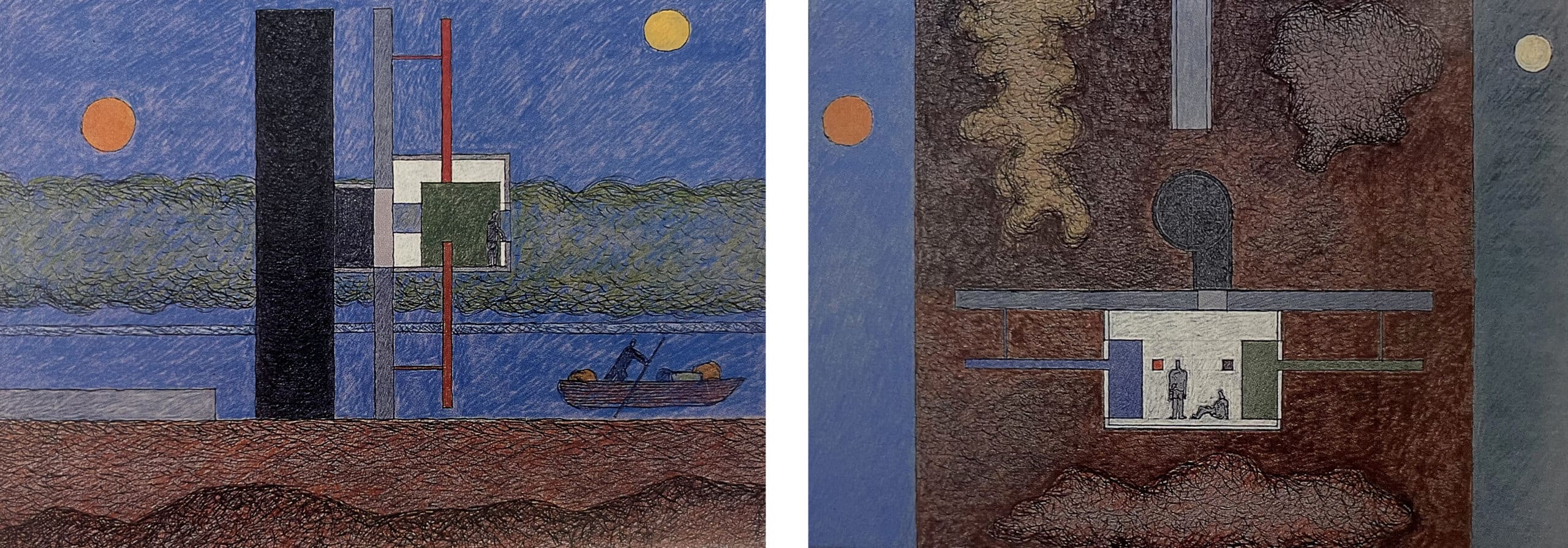

The Waiting House hides behind the towers like a miniature. The relationship between the small house and the towers is similar to the relationship between the house and the cemetery in Cemetery for the Ashes of Thought (1975). The house marks the end of a path, the last frame. The representation of the interior of the house is a juxtaposition between its plan and its section. This ambiguity reaffirms the meta-architectural character of the project. The design of the house comes from this overlap. The internal environment is unique and transparent. The entrance is through a path, which leads to the ‘field’. Then there is a vertical circulation cylinder, which leads to a small landing, where the inhabitant finds the wall plane, crosses it, and arrives home. This gradation is similar to Wall Houses 1, 2, and 3 and can be understood as a strategy of memorability—demarcations that bring awareness to everyday actions.

A table is proposed as a collective space for the tower dwellers, located in the open ‘field’ in front—‘The 16’x 3′ table is placed in front of the field house and then each day is moved and placed in front of a following tower; when a cycle is completed another cycle is put into motion.’[25] The intense contrast between the scale of the tower and the scale of the table points to a sort of miniaturization of the collective. The individual tower opposes the table, which is fragile and communal. The table is the reaffirmation of the fragility of social encounter, shrunk in the face of individual isolation. The monumental scale of the tower oppresses it. The temporality of Hejduk’s proposal can be understood by the cycles of the inhabitants, as forms of disappearance, which rehearse the scenic characteristics of his later work. Inhabitants move within each building and between buildings across the city through time. The table is a counterpoint of sociability for the inhabitants who live in isolation.

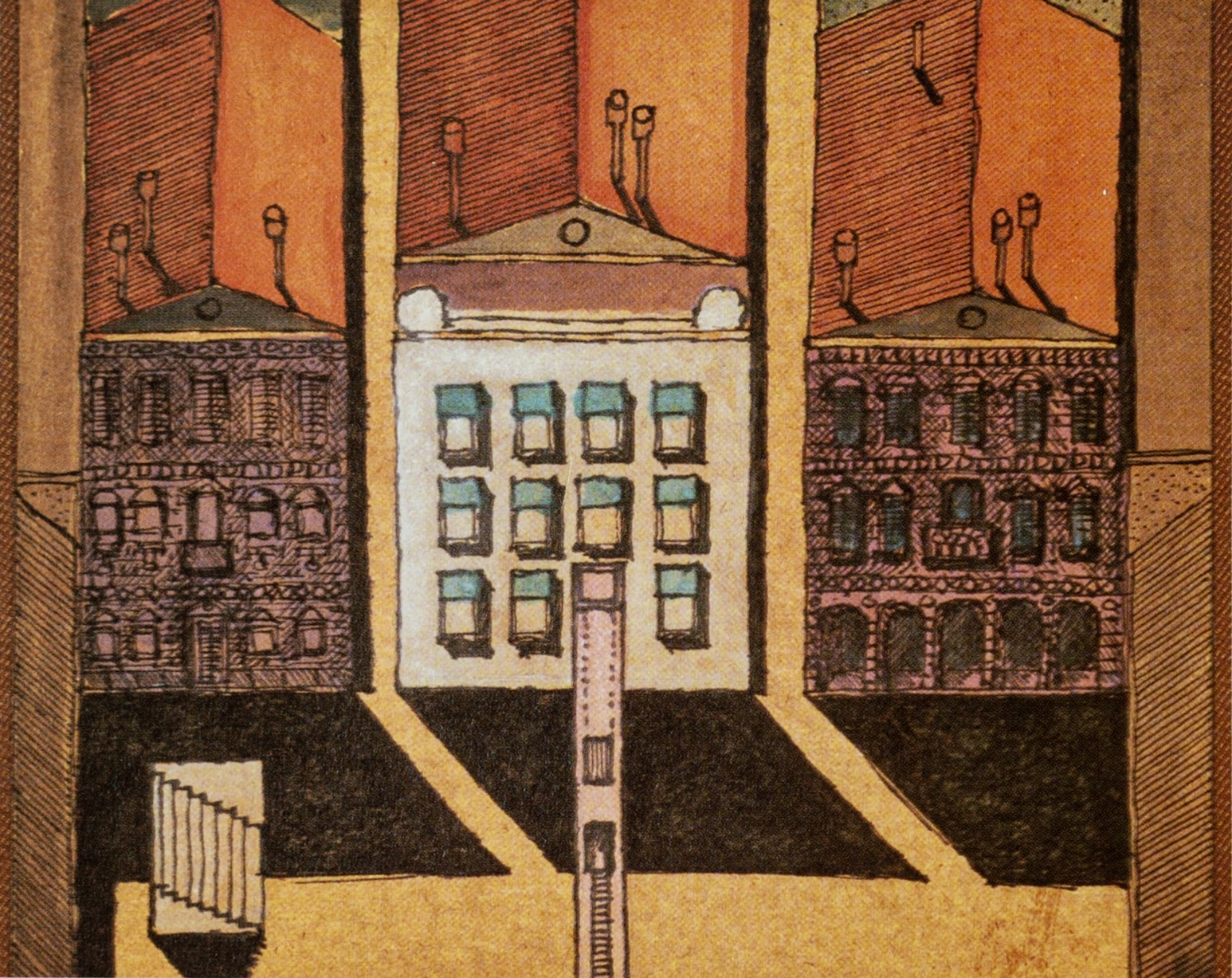

Located elsewhere, the House for the Inhabitant Who Refused to Participate is inserted into a pre-existing urban fabric so as not to touch it. Hejduk doesn’t explain exactly the location of the square. It could be anywhere in Venice, away from the towers. The facade is defined by a continuous plane, typical of the Wall Houses, which hides the infrastructure of the house. There are a series of interstices: lateral (the building does not touch the neighbours), between units of the House (each activity takes place in one of the 12 volumes suspended on the facade, invading the field), between floors, between circulation elements, and between structural elements. This detachment results in a heightened distinction between the new and the existing city, which strengthens our perception of the passing of time. Similarly, the Thirteen Watchtowers are also detached from the city surrounding it, clearly legible as a new, separate insertion in the city’s horizon.

In the description of the House, Hejduk inscribes a latent risk in the public-private dynamics between the house and the small viewing tower at the centre of the square. This tower is like a camera, a one-way observation apparatus: any citizen can climb the tower to observe the inhabitant in refusal without being seen. The perversity of the citizen who observes from the hidden tower puts him at imminent risk of becoming a prisoner of his observing impulse. The door is the risk agent— ‘There is only one risk for the hidden observer. Another citizen may release the overhead tower door consequently enclosing within the tower the citizen observer.’[26] Hejduk erases the distinction between the building itself (as materiality) and the mutable relationships enacted within it. Architecture appears as an interplay of objects, geometry, and action. The concept of mobility is central to arriving at what he later calls the ‘architecture of pessimism’. In Venice, Hejduk is still working on inhabitation through static buildings. In his later projects, the structures themselves are movable—a radicalization of the scenographic characteristic of this architecture in Venice.

In the square in front of the house there is a staircase. Hejduk does not mention the ladder in his descriptions, and it is interesting to note that in Eisenman’s proposal for Cannaregio, a similar object also appears loose in the midst of the geometric composition organized by a grid. The stairs are a path to nowhere, or towards a precipitous drop: the last landing is narrow. On the other hand, the staircase is a theatre—it is the possibility of observing observation. The inhabitant who sits on the steps can observe the dynamics between the house and the tower. People on the square can observe the observers on the steps. Hejduk uses a principle of composition that is simple. Form does not carry meaning in itself (it is not codified). Meaning is achieved through the acting subjects within and around it. This can be understood as a form of openness, of ‘open-endedness’. The project does not end in itself but opens up a series of possibilities. This characteristic also intensifies throughout the architect’s career and can be recognized both in projects considered ‘optimistic’ and ‘pessimistic.’

It is possible to identify a gradient in the material language of the ensemble, which varies between spaces of total protection and containment (hot), to spaces of total transparency (cold). In each tower there is a fireplace and a series of exposed pipes, which cross the building vertically. In the house, glass defines the materiality of the suspended spaces, in a cold interior, marked by vigilance. This gradient reinforces the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion underlying the entire narrative of the project. The citizen who participates is excluded from the tower; the citizen who refuses is included in the square.

Hejduk’s proposal for Cannaregio is physically static and temporally malleable. The interweaving of programmes and actions throughout the city, organized among the three buildings, draws the answer to Dal Co’s question. At the urban scale, the proposal operates as a utopia: an imagined cosmos with a beginning, middle, and end. This can be understood as optimistic in Hejduk’s conceptual logic. Pessimism in his work is linked to a scenic amplification: a gradual release from static forms (architecture as an overture to unfinished choreographies of human experience, a propelling force that inaugurates, suggests, and supports possible events). Cannaregio’s proposal is neither a mask nor a chronotope. There are three fixed buildings, albeit in an abstract place. In this sense, the ensemble carries two interpretations and appears exactly at the threshold between Hejduk’s inheritance of a classic modern language and his radical inventions that followed. The ensemble appears as an answer to the Cannaregio question but goes beyond its borders without pragmatically ‘solving’ it. In this sense, Hejduk’s proposal can be understood as an argument. It is a form of resistance that articulates a series of denunciations against individualism, the passage of time, anxiety, and public space.

Notes

- Thirteen Watchtowers of Cannaregio (with Waiting House) is presented by Hejduk as Waiting House and also as Wall House 4.

- As Mary McLeod has noted, it is easier to agree on what the postmodern was not, than on what it actually was. (Mary McLeod, ‘Architecture and Politics in the Reagan Era: From Post modernism to Deconstructivism’ in Architecture Theory since 1968, ed. by Michael Hays [Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010], 680.) Despite the hybrid characteristics of what became known as postmodernism in architecture in the United States – Europe axis, it is possible to infer a few main articulating tendencies: a discursive, self-reflective character; the disbelief in a large-scale or utopian social transformation project; the weakening of the notion of control and power. (Reinhold Martin, Utopia’s Ghost [Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010], xiv.) This period appears more recently in the theoretical production of North American historians as an open, inconclusive project (refer to Michael Hay’s Architecture’s Desire [Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010] and (Martin, ibid.).

- K. Michael Hays, Hejduk’s Chronotope (An Introduction) (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 8.

- In the publication Sanctuaries: The Last Works of John Hejduk Michael Hays gathered many of Hejduk’s paintings of angels. They are a culmination of the spiritual dimension of the masques. The idea of a ‘negative restoration’ is an alternative return of architecture to its cultural and ethical potential through a poetic and artistic expression embedded in cultural myths. The pictorial representation of angels is an intensification of Hejduk’s denial of utopian modern programmes. Through the assembly of simple geometries, abstract spatial cues and types, architecture’s collective agenda is restored. It opens an alternative path to do with rituals and human experience beyond the physical.

- Hays, Hejduk’s Chronotope, 12.

- Optimistic programmes can be understood as a functional agenda for buildings in which a dimension of collective accomplishment was embedded. It implied architecture’s responsibility and promise of a contribution to the betterment of society in non-individual terms. Early modern architectural language was consolidated while collective hygiene was a central concern. The use of new technologies, such as steel and glass, enabled a new aesthetics of transparency and thinness which supported the exchange of light an air between interior and exterior spaces.

- Stan Allen, ‘Nothing But Architecture’ in Hejduk’s Chronotope, 87.

- First published as Progetto e Utopia in 1973.

- Allen, 80.

- In the introduction to Five Architects (1975), which brought together projects by Charles Gwathmey, John Hejduk, Michael Graves, Peter Eisenman and Richard Meyer, Colin Rowe emphasizes the absence of meaning and that architecture became nothing more than the illustration of program as a direct expression of its social function. Rowe suggests that the semantic emptying of architecture in modern times would become one of its main weaknesses. Architecture as a rational approach to building, as a logical derivative of functional and technological facts. The intensity of a social vision embedded in architecture dissipated as modern architecture proliferated across the world, as it standardized, became more basic and economical. According to Rowe, the ideal of democratizing modern architecture led to a rapid devaluation of its content. Rowe narrates the emergence of stylistic phases since the 1960s as evidence of the impossibility of utopian architecture at that time.This transformation is understood by him more as an evolution in continuity with the modern than as its rupture.

- Detlef Mertins, ‘The Shells of Architectural Thought,’ in Hejduks’s Chronotope, 26.

- Allen, 90.

- Mask of Medusa (1985) is a work in itself: an autobiographical artistic project that brings together drawings, texts and poems, organized so that drawing and word appear intertwined as a single form of expression. It was printed by Rizzoli Publishing House in New York and, despite its size (23cm x 31cm x 3cm) and weight, it’s a delicate object, distinguished by the textures of its cover and pages, and by the meticulous and sparse visual diagramming. Lorraine Wild’s graphic design stands out for generous paragraph spacings that create new drawings with the edges of texts and interviews. The texts appear decentralized, enigmatic illustrations coexist with architectural drawings. Manipulating the book is like touching an original drawing, as if the work had become another drawing, with new orders of thickness and opacity. ‘A drawing on a piece of paper is an architectural reality.’ (John Hejduk, Mask of Medusa: Works 1947–1983, ed. by Kim Shkapich [New York: Rizzoli International, 1985] ,69). He suggests continuity between architecture and its modes of representation, so that it is not possible to separate drawing and reality in architectural design. In this sense, both the built and the projective thought exist: ‘They are.’

- Allen, 88.

- Hays, 7.

- Ibid., 7.

- Allen, 83.

- Ennio Concino omitted from the introduction the participation of Giuseppina Marcialis who co-authored Gianugo Polesello’s proposal as presented in page 128 of the book. Ennio Concino, ‘Dinamiche urbane di una periferia: noa su Cannaregio’, in 10 Immagini per Venezia: mostra dei progretti per Cannaregio Ovest’. Venezia, Al Naopleonica, 1 Aprile–30 Aprile, ed. by Francesco Dal Co (Roma: Officina Edizioni, 1980).

- Dal Co, 122.

- Hejduk, 83.

- Michael Sorkin, Exquisite Corpse: writing on buildings (New York: Verso, 1991), 182.

- Hejduk, 355.

- Hejduk, 58.

- Lais Bronstein, ‘Arquitetura e Solidão. John Hejduk em Berlim’ in Revista de pesquisa em arquitetura e urbanismo (Risco, 2003), 58.

- Hejduk, 83.

- Hejduk, 355.

This research was developed with the support of the Capes/CNPq scholarship of the Graduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo between November 2015 and July 2018.

Marina Correia obtained her architecture degree from The City University of New York, she holds a Master in Architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design and a Ph.D. in History of Architecture and Urbanism from the University of Sao Paulo. Her doctoral thesis Miniature Volume: John Hejduk and Venice explores through the work of the American architect John Hejduk the critical dimension of architecture in the late 20th century, presenting the close relationship between poetic language and the socio-political agenda of this period. In 2013 she founded Atelier Architecture and Urban Design, an international design practice that supports actions for the democratization of culture and education, currently based in Rio de Janeiro and New York.

– Stan Allen and Marina Correia