What Lies Beneath

‘The people of Sydney ought to be afraid of the sharks, but for some reason they do not seem to be,’ recalled Mark Twain in his 1897 Following the Equator. The travelogue was the result of an 1895 lecture tour that Twain, by then 60, had made of the British Empire in an attempt to dig himself out of bankruptcy. He had lost $100,000 in the Paige Compositor, a huge machine, as shining and enigmatic as a piece of Suprematist sculpture, that never delivered on its promise to mechanise the laborious process of typesetting and printing.

After a year on the lecture circuit, Twain had settled his debts and immersed himself in the other side of the world, recording his fascination with the rapid modernisation that was taking place in the wilderness down under. Australia, he discovered, was miles ahead of both Britain and America in its determination to build:

‘I have seen a costly and well-equipped, and architecturally handsome hospital in an Australian village of fifteen hundred inhabitants. It was built by private funds furnished by the villagers and the neighbouring planters, and its running expenses were drawn from the same sources. I suppose it would be hard to match this in any country. This village was about to close a contract for lighting its streets with the electric light, when I was there. That is ahead of London. London is still obscured by gas.’

The shark, however, seems to have been a particular obsession, featuring multiple times in Following the Equator. Twain reports on them – ‘the shark is the swiftest fish that swims. The speed of the fastest steamer afloat is poor compared to his.’ Shark-fishing tops his list of social pleasures – ‘Sydney Harbour is populous with the finest breeds of man-eating sharks in the world. Some people make their living catching them; for the Government pays a cash bounty on them.’ The shark even stars in a somewhat tenuous short story of how Cecil Rhodes made his millions: by finding a ten-day-old London newspaper in the belly of a ‘nineteen-footer’ (news was already 50 days out of date by the time steamships had brought the papers to Sydney Harbour).

Silver, shimmering bodies containing a risky promise of fortune. In the context of the failed Paige Compositor, perhaps the shark had become the vessel for Twain’s misplaced hopes, or maybe it was a symbol for what can happen when one is struck by an insatiable need to modernise. ‘Tragedies’, he wrote, ‘have happened more than once’.

Ever-prescient, in 1895 he foresaw what by the 1920s and 30s would become a national emergency, when shark attacks in Australia reached an all-time high.

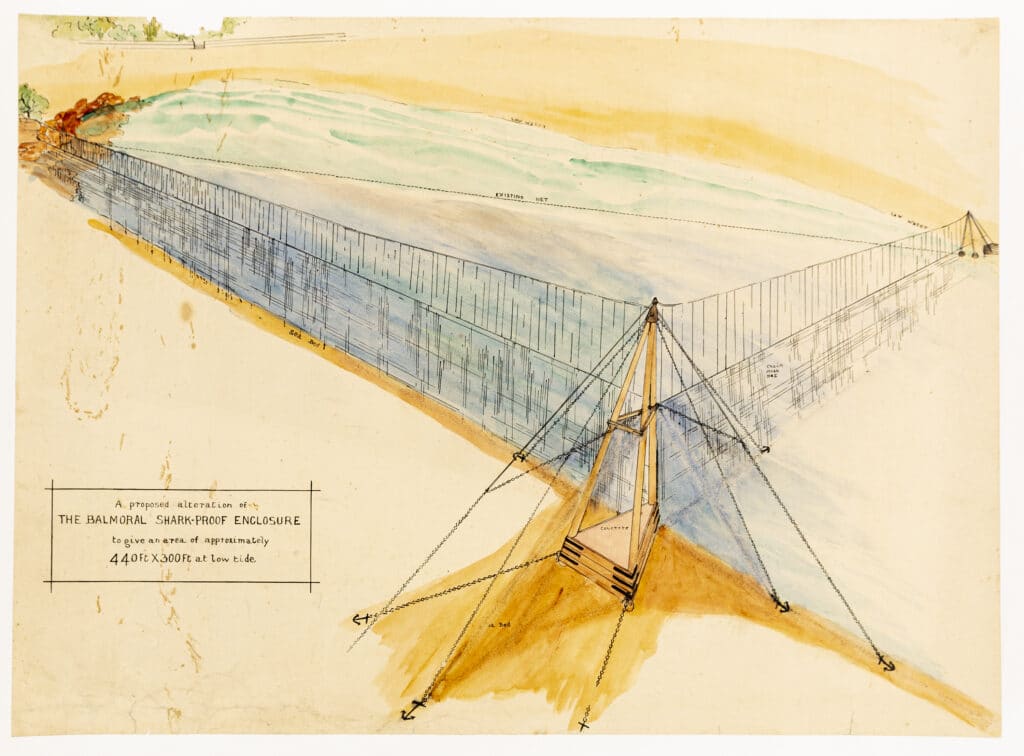

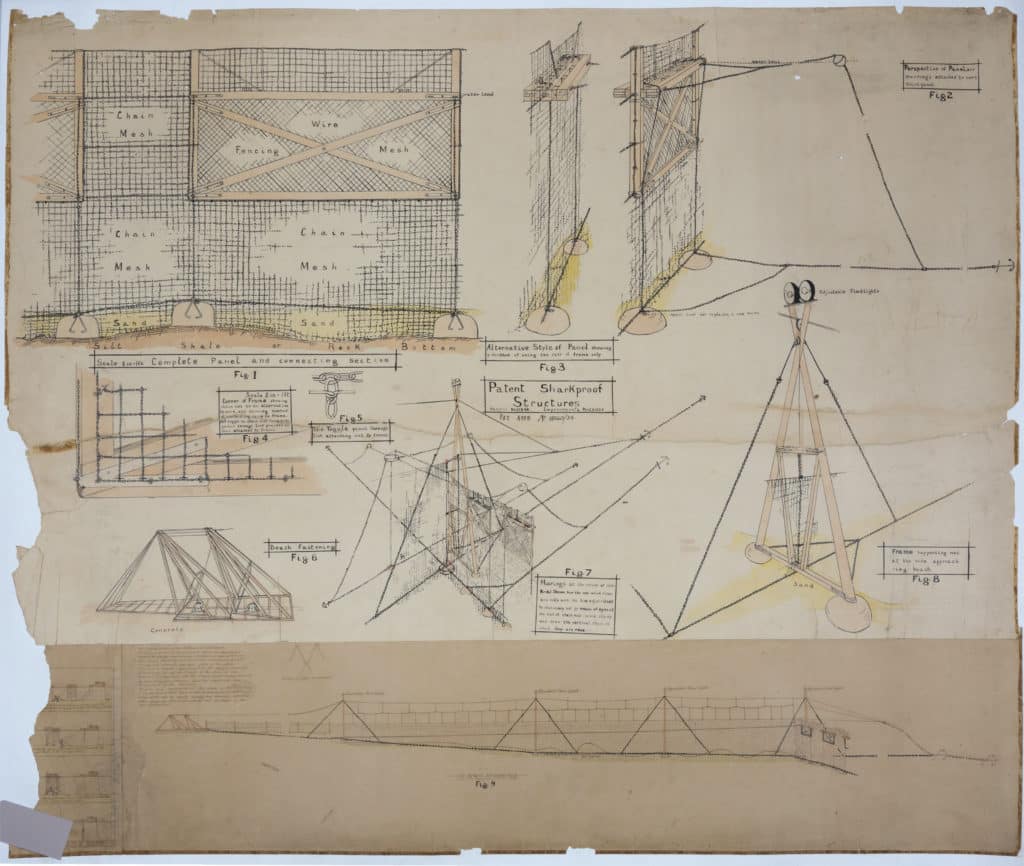

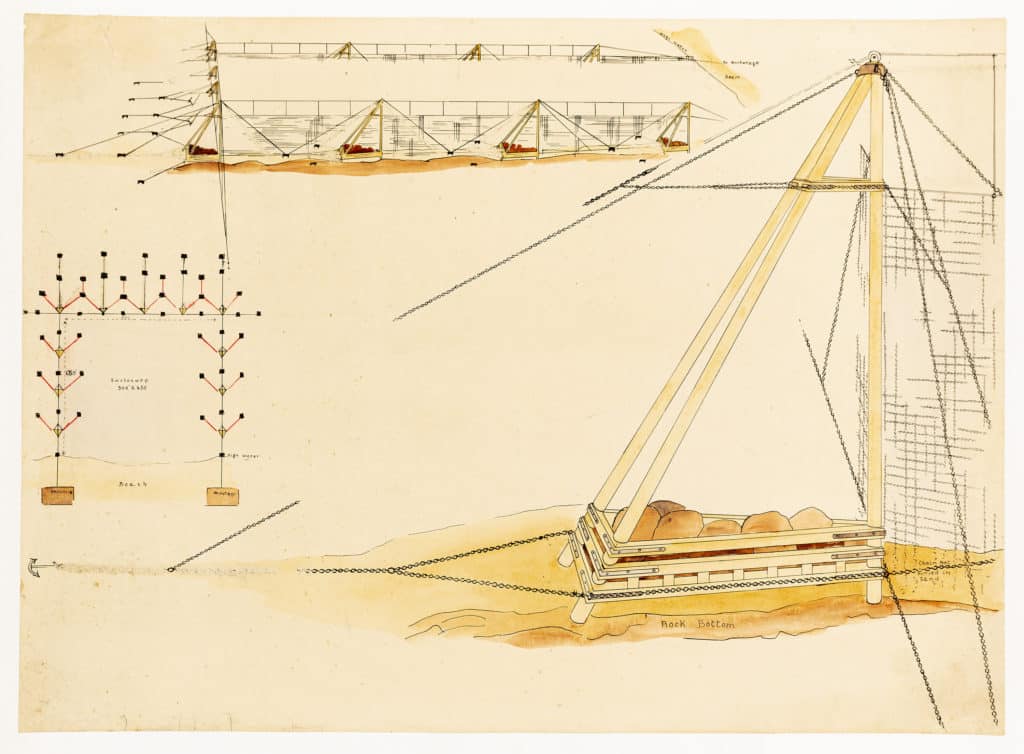

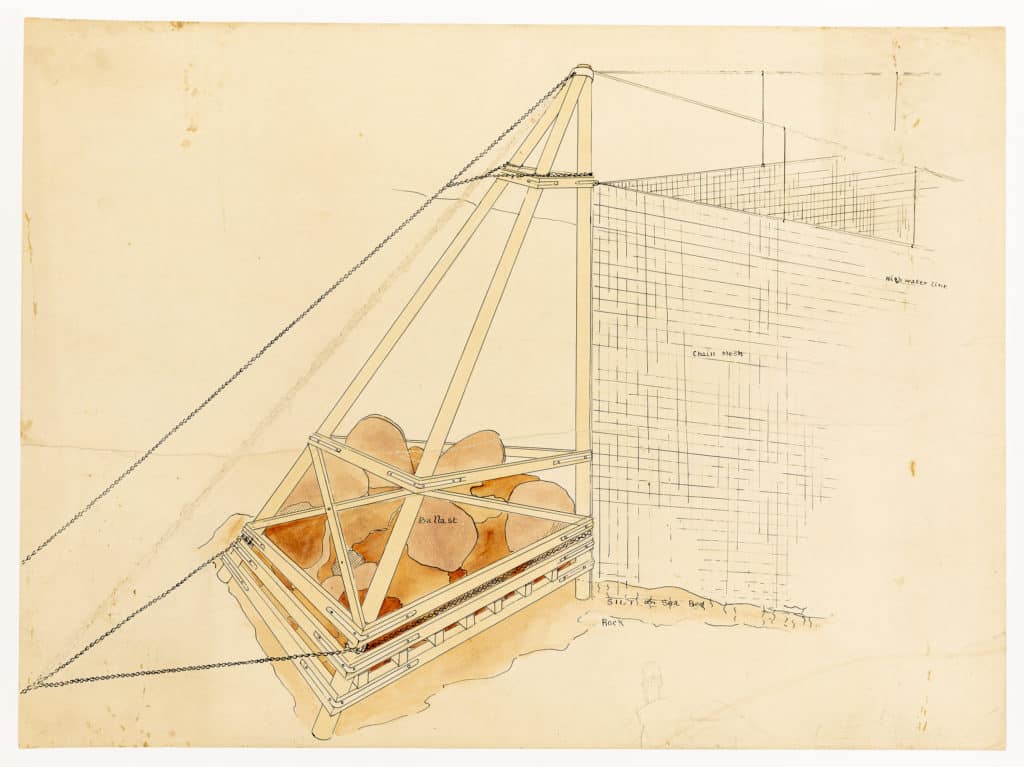

This set of watercolours, attributed to an ‘Unknown Australian’ and made at the zenith of the attacks, takes an almost picturesque approach to extending and reinforcing the enclosure at Sydney’s Balmoral Beach. The first sheet shows a watery expanse drawn from the farthest point at sea, taking a view to shore. Faint lines intimate a chain mesh net that marks a safe-swimming area of 132,000 feet. With a seeming calm over the water, suggestive of early morning and the promise of a full day’s swim, the perspective invokes less a scene of danger than an artwork by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. The three other drawings for the proposed enclosure present the grim reality of what lies beneath, and it is the large composite of perspectives and elevations that makes blood run cold. Intersecting walls of chain and fencing are ballasted along the seabed by moorings and a series of timber frames topped by floodlights. Meanwhile even more chains tie-up to a series of interconnected rafts that raise and lower the chain wall with the tide.

Shark-safe enclosures had been popularised in South Africa by the 1900s, most notably at Durban’s Ocean Beach, as British tourists sought to translate the English beach to the coastlines of the Commonwealth. Australian visitors caught on and, eager to bring seaside leisure home, imported the enclosure concept. Sharks ‘will continue to avenge the reckless folly which courts destruction, but they can be shut out’, reported a newspaper from the time. ‘A reasonable amount of pleasure can be enclosed by fencing in liberal sea spaces to accommodate the majority of those who desire to wash and to bathe, and be cool and clean.’ Soon numerous patent proposals, such as the one shown here, were developed for enclosures that could keep a large swimming area safe at any tide.

But as more enclosures were raised and swathes of wild shores made safer, more social barriers were erected too. With limited areas for safe swimming available, morally righteous municipalities fretted over mixed-gender bathing. And further, while the newly ‘civilised’ beaches allowed British tourists to enjoy leisure time, they cut off sections of coast from the indigenous populations who had been using it for centuries. Reading the travelogue of Mark Twain, who was forthright in his critique of American Imperialism, one wishes he had been as outspoken abroad. Sadly, he seems to have saved up his zeal for the sharks.

– Florian Beigel and Philip Christou