Where Words Fail

– Cyril Babeev and Matt Page

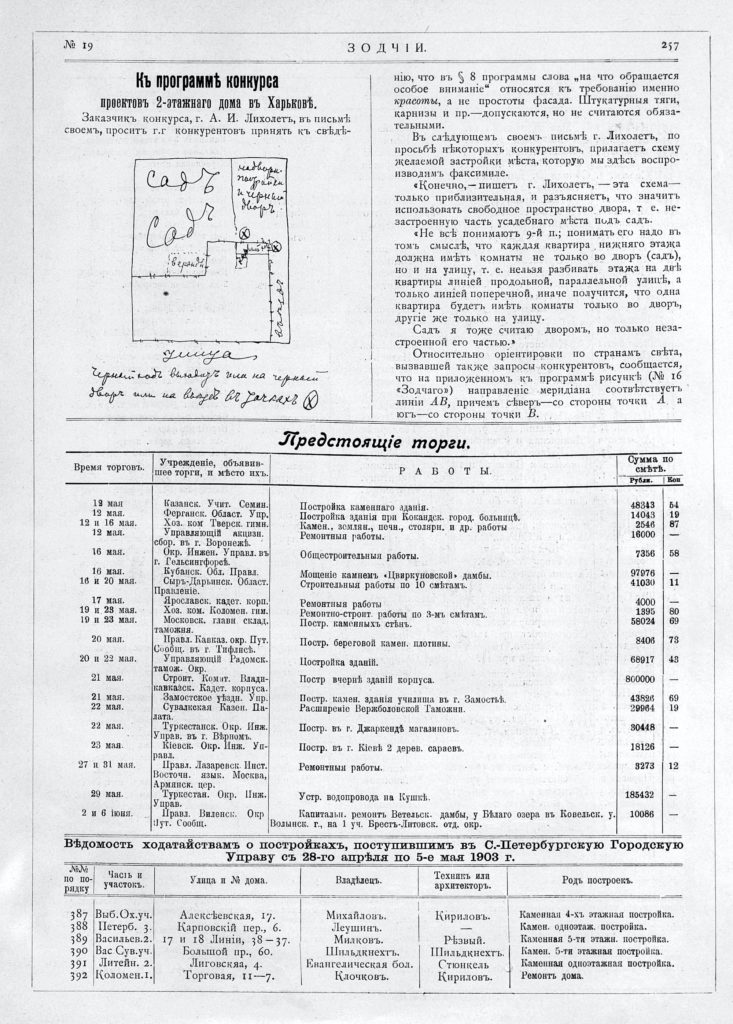

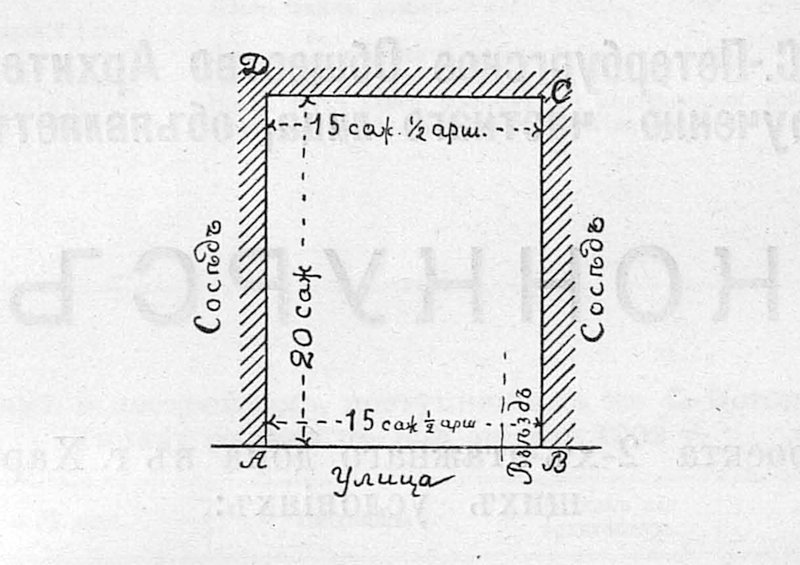

This drawing, a sketched site plan annotated in cursive old-Russian, was published in May 1903 in the Saint Petersburg-based architecture magazine Zodchiy (Зодчій). [1] The plan describes a nearly-square plot sited perpendicular to a street (ulitza, улица) and divided into three areas: a house, represented by a white void; a garden in the top left – so important that it commands the biggest lettering and the word garden (sad, сад) is written twice; and a driveway running along the side of the house and leading to a courtyard with a garage and stable. Two circled ‘X’s mark potential staff entrances at the rear of the house.

The plan was not drawn by an architect, but rather by the patron of an architectural competition launched by the ‘Imperial Association of Architects of Saint Petersburg,’ the founders and editors of Zodchiy, to design a two-storey house. The drawing was an eleventh-hour adjustment to the competition brief, which had been set in the preview issue on behalf of Arseniy Ivanovich Likholet, a middle-class resident of Kharkiv, a city now in Ukraine. The original brief was accompanied by another plan, drawn in a more formal fashion, which shows the dimensions of the plot: 20 sazhen (сажень) (about 140ft) by 15 sazhen and half of an arshin (аршин) (just over 100ft).

Alongside the first plan, Likholet also listed eight stipulations for the design, seven of which relate to the design of the house itself and the last to the site. His requirements for the interior are remarkably particular, increasing in specificity as he moves from the services for the house to the composition of the ground and first floors. The basement, he states, should be equipped with a boiler room, a coal store, a laundry, accomodation for a janitor, and four cellars. The ground floor of the house, which should be raised up two arshin (six feet) from street level, should comprise two apartments that should be split into either five rooms each, or six rooms in one and four in the other, or four rooms in one and five in the other. In turn, each apartment should have bathrooms and water closets, rooms for servants, and kitchens with pantries. The first floor should consist of one apartment subdivided into eight or nine rooms, and these rooms should be: a study (288sq.ft), one living room (414sq.ft), a lady’s sitting room (144sq.ft), a bedroom (216sq.ft), a child’s bedroom (216sq.ft), another child’s room (216sq.ft), dining room (306sq. ft), spare room (216sq.ft) and a chambre de bonne (90sq.ft). And, with unspecified measurements, a kitchen, a buffet and dining room, wardrobe, cold and warm pantry, a bathroom and water closet, and a room for servants and a cook. The height of the ground floor should be five and a half arshin and the second floors should be five and three quarter arshin. After exhausting the interior, Likholet takes a moment to consider the exterior of the house, stating that the facade should be constructed in brick with stucco cornices; importantly, though, the facade must be ‘prostoy, bez vichurnosty’ – ‘simple and without pretentiousness.’

The specificity of Likholet’s brief in relation to the interior of the house shows a certainty in his mind about how the internal space of the building should be organised. In words, he dictates such a stringent programme that the poor architects entering his competition have few choices beyond deciding the colour of the wallpaper. In this context, the sketched plan submitted for the later issue of the magazine, which was enclosed with yet another list of stipulations for the design, is an interesting object and two concerns might be inferred from its last-minute submission. First, that Likholet – despite opening the competition to an audience of architects – was clearly anxious to give them a strong guiding hand; and second, that while the interior space of the house could be subjected to measurement and determined by the volumes of its rooms, planning the site around the house was a much harder task – and one that the earnest Likholet was doubly determined to get right. As a drawing that figures in a process of design – or, more accurately, a process of commission – the sketch plan of Likholet’s Kharkiv plot describes the inverse of his written brief. Where the brief delineates the interior spaces that are represented as a blank void in the sketch, the actual open, exterior spaces of the site are subject to his efforts to circumscribe and divide. In this sense, the sketch suggests that in trying to apply his officious method for the inside to the outside, words and measurements fail him, instead he needs to turn to drawing to communicate.

Postscript –

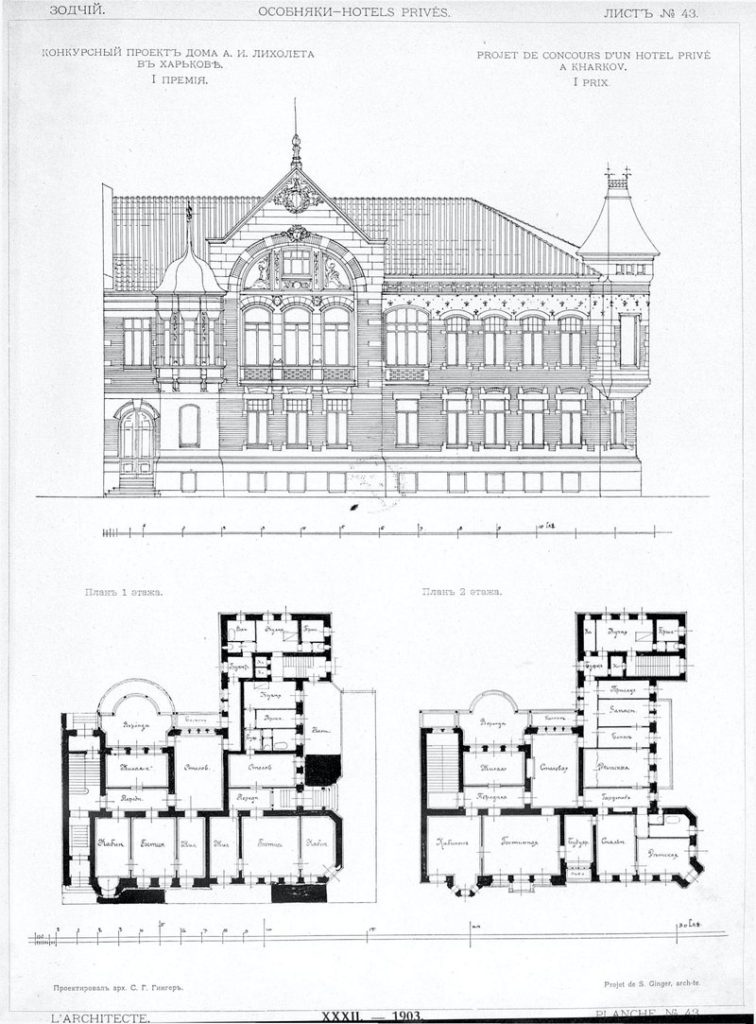

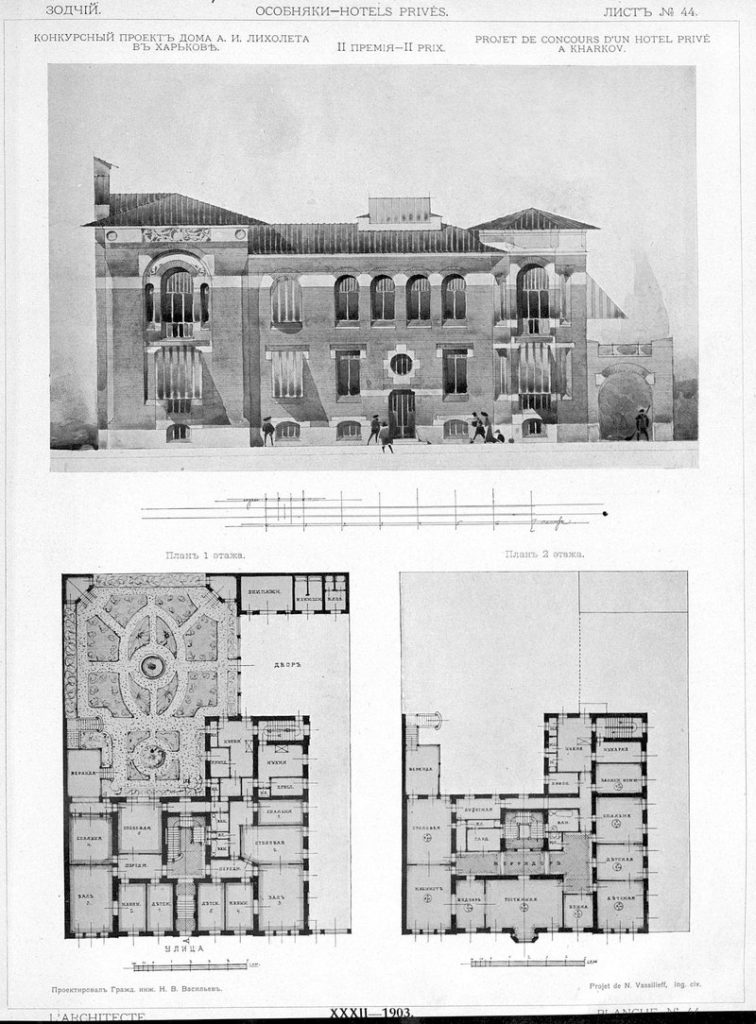

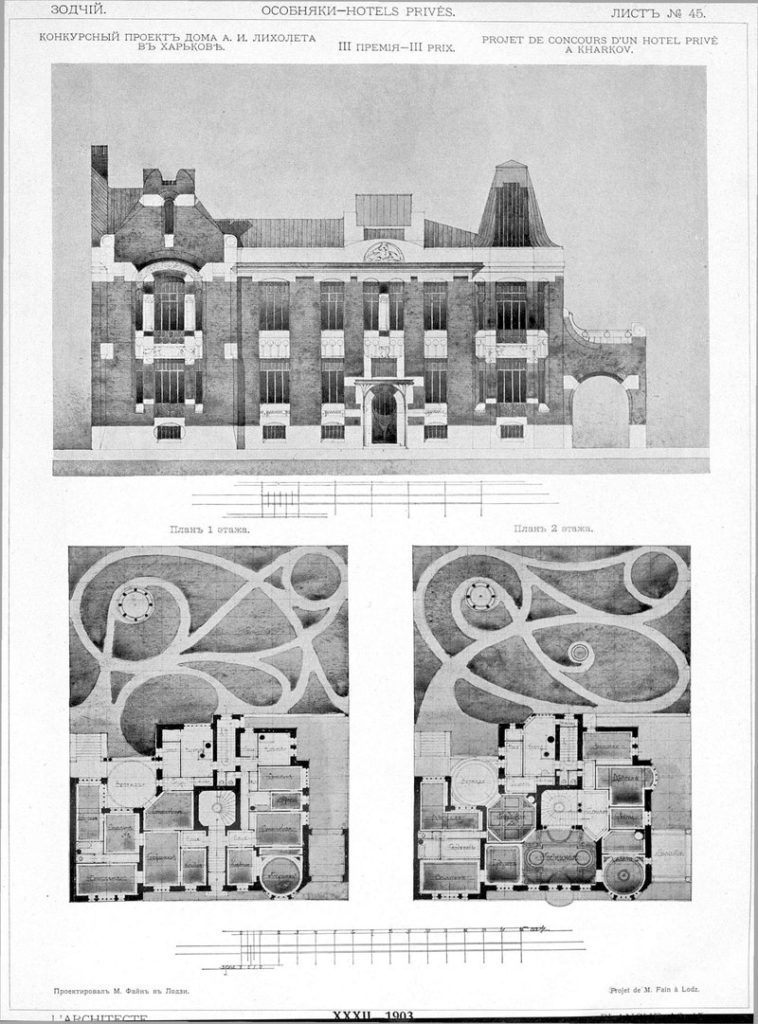

In a later issue of the magazine, the Imperial Association awarded first, second and third prizes to three proposals. Only one of the authors appears to have paid any real attention to Likholet’s sketched plan…