Writing Prize 2020: Domestic Space, Registered

– Laura Bonell and Daniel López-Dòriga

Around 200 AD, a map of the city of Rome was carved on marble at a scale of approximately 1:240. It measured 18 meters wide by 13 meters high and comprised 150 marble slabs hung on an interior wall of the Templum Pacis.

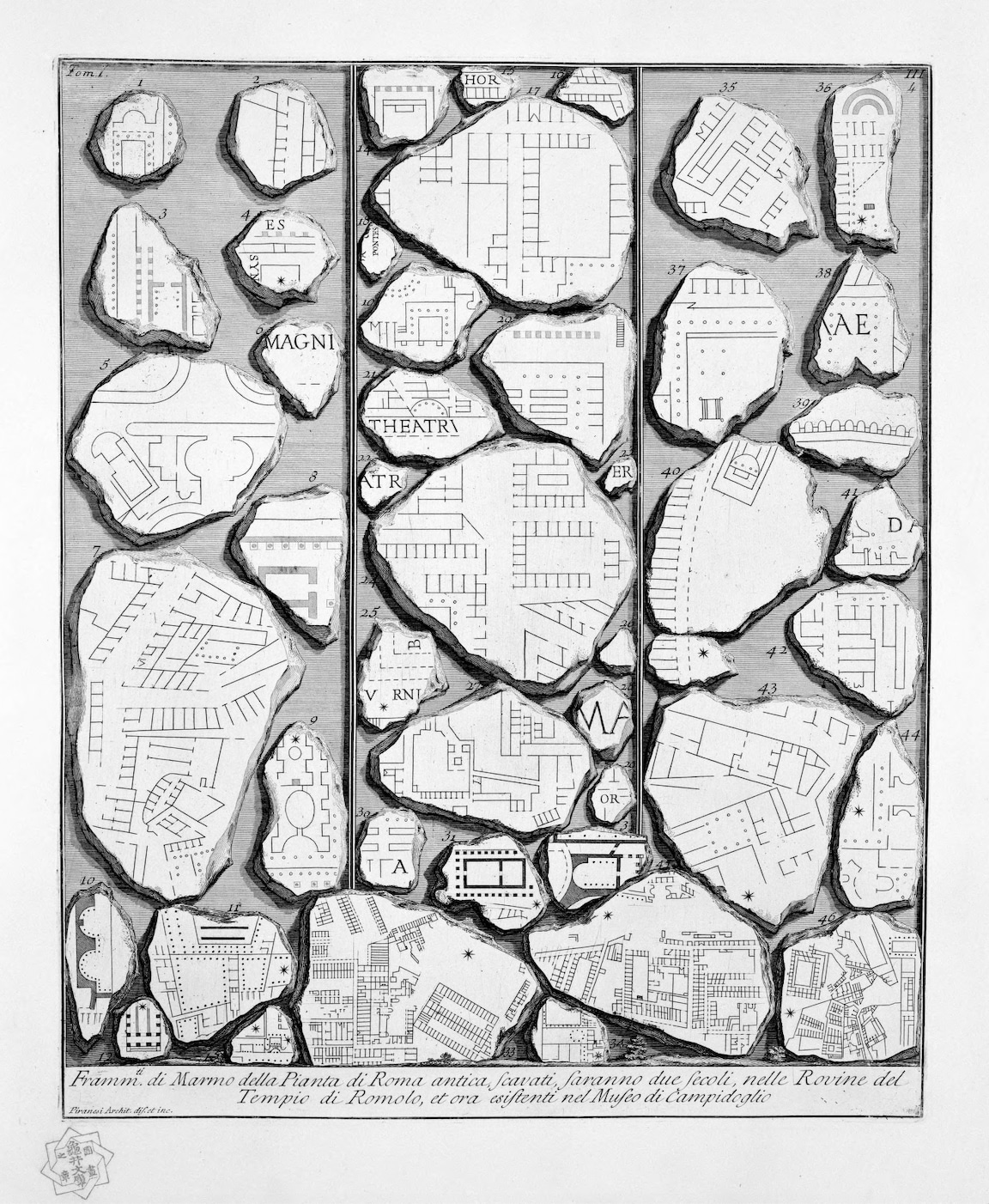

The Forma Urbis Romae or Severan Marble Plan, as it is known, is thought to have collapsed and disappeared after the metal clamps fixing it to the wall were stolen, or after it was dismounted and converted into construction material for new buildings. The first recovered pieces were found in 1562 and kept in the hands of private collectors until 1741 when the city of Rome acquired them. Many scholars have studied the fragments to learn more about the original map and the city it represented. Giovanni Battista Piranesi drew them in a series of engravings included in the first volume of Antichità Romane in 1756.

The 1186 fragments found so far are said to amount to 10-15% of the original plan. The rest are allegedly scattered around Rome, inside the walls of palazzos and the foundations of churches.

Whether the plan had a functional use, represented the power of the city, or if it was purely decorative is unknown. But with the city’s walls and columns precisely incised on stone, it offered a representation of Rome as a sum of interconnected spaces: interior and exterior. All lines delineated the same way, with no difference made between small private housing and the public temple.

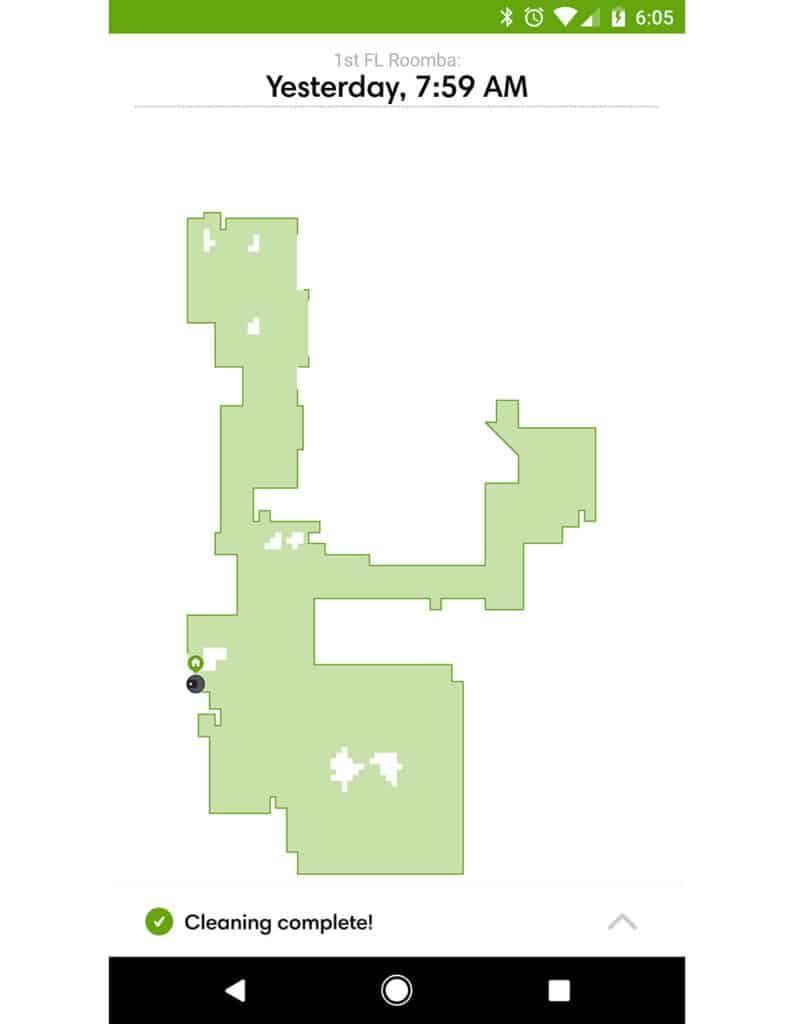

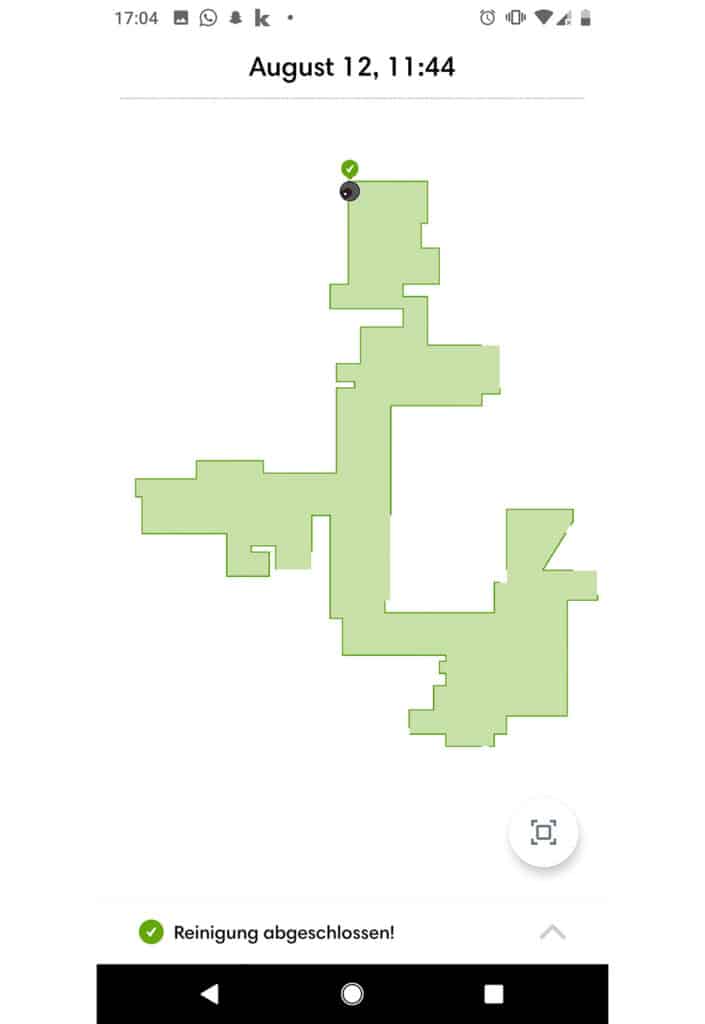

In 2018 the American company iRobot presented its latest Roomba model, the Roomba i7+, a vacuum cleaner that was able to create a map of your home as it cleaned it.

As a way of surveying the domestic space, the method used by the Roomba sensors bears a closer resemblance to how NASA robots explore and document the surface of Mars than the linear way in which architecture has been traditionally measured and drawn. The resulting plans – visible to the users via an app – do not define the architectural construction of the rooms but instead, empty floor space with all the walls and furniture removed.

By using the vacuum cleaner users legally agree to share their home information with iRobot, who then store it in their own servers, supposedly only accessible to authorised people. The announcement of this new model raised many concerns about privacy and consent, but stock share prices in the company soared the following year.

While it is too soon to know what iRobot could do potentially with this information, it remains that stored in a data centre somewhere, is a virtual map with geolocated floor plan layouts of millions of homes around the world.

The Forma Urbis Romae is probably one of the oldest graphical representations of the domestic space ever recorded. The other, while not the most recent, might be the most contemporary; graphical information of the home turned into data and traded into currency.

Interestingly neither of them uses paper, ink, graphite or paint. They stand at either end of centuries of drawings that were produced by staining a surface. In the 1800 years between Imperial Rome and the Roomba, technology has evolved to the point where what was first engraved by hand in stone is now automatically written in binary code by a vacuum cleaner and represented in our screens as a sum of immaterial pixels.

What has not changed, however, is the need or will of human society to survey, document and register the domestic space, whatever the motive. Despite the reasoning (and in spite of the scope of their ambition), neither of these maps can be perceived in their entirety. Only as parts, visible fragments of an invisible whole.

The Marble Plan aimed to represent Rome in its entirety, but what we see today are pieces, the result of the arbitrary forces of physics and historical events. The rest is likely turned to dust and hidden in walls. The Roomba plan intends to represent the wide world, or at least its built parts, one household at a time. But the screen of our cell phones only shows us our own rooms, and the ones we have decided to clean. Everything else is codified as ones and zeroes and concealed behind inaccessible firewalls.

This fragmentary vision of the world perfectly encapsulates our current time. While we were never able to physically experience the entirety of the world, never has this been truer than the present moment.

We write this in the late spring of 2020 as European cities gradually begin to lift restrictions of movement, but we don’t know how long this will last or if it’s ever going to happen again.

The domestic space has become the centre of our lives and the only place for any person whose work is not ‘essential’. Moving up and down our homes in varying degrees of emotion, we slowly erode the floor with the drawing of our feet. We have peeked into the windows of our neighbours from afar; and into the homes of our friends, family and co-workers from screens, to enlarge the mental space of our day-to-day reality and of its inhabitants. Isolated yet hyper-connected, we have been confined between the physical space of our own homes and the immeasurable virtual space. Caught between stone and pixel.

Laura Bonell and Daniel López-Doriga share the architecture studio Bonell+Dòriga, founded in Barcelona in 2014.

This text was a prize winner in the long form category (1000–1500 words) of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2020.

– Laura Bonell and Daniel López-Dòriga