Zünd-Up’s Great Vienna War of Dreams

‘Only the realization of utopias will make man happy and release him from his frustrations! Use your imagination! Join in… Share the power! Share property.’ Wolf Vostell, Cologne 1969 [1]

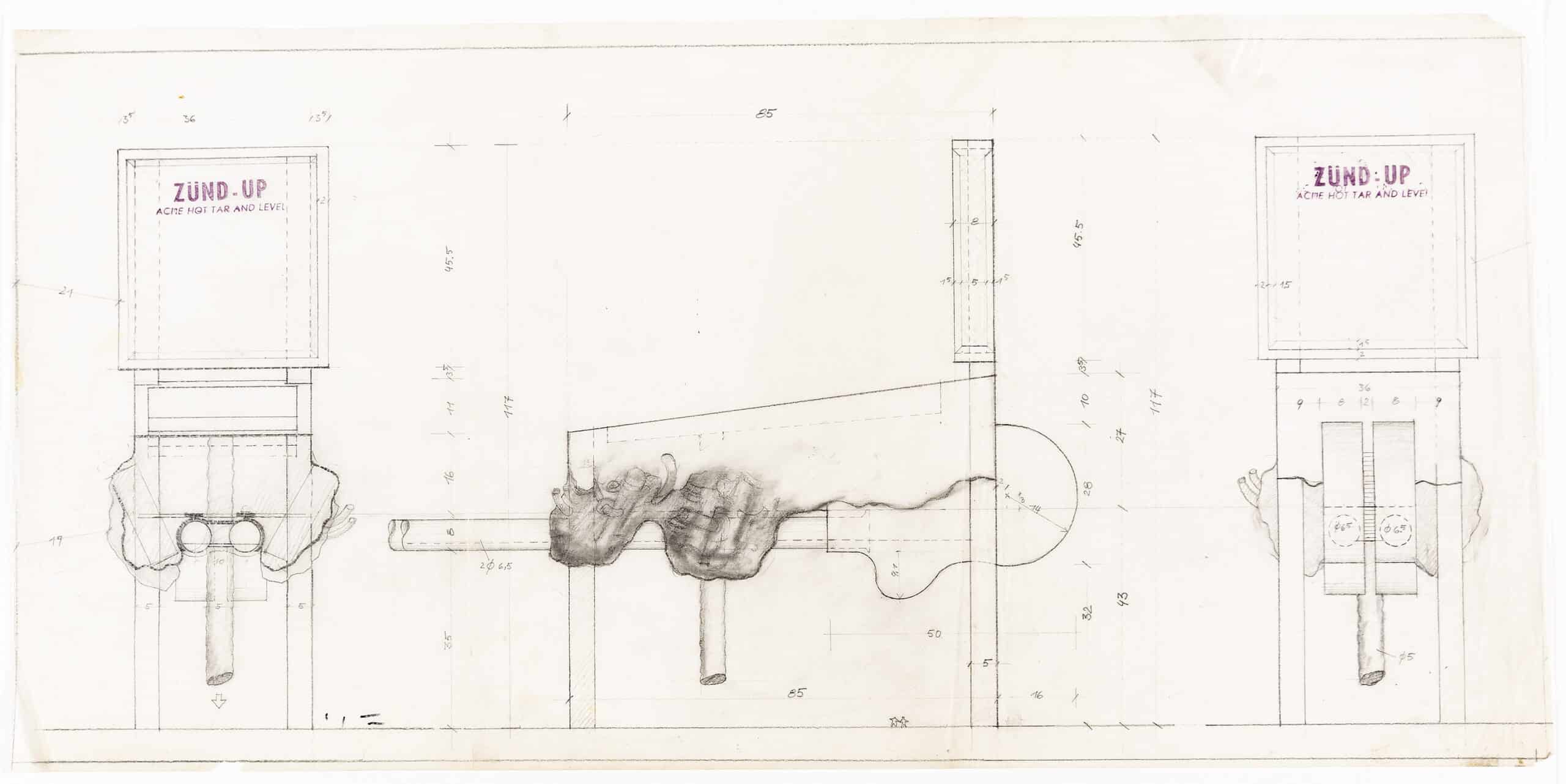

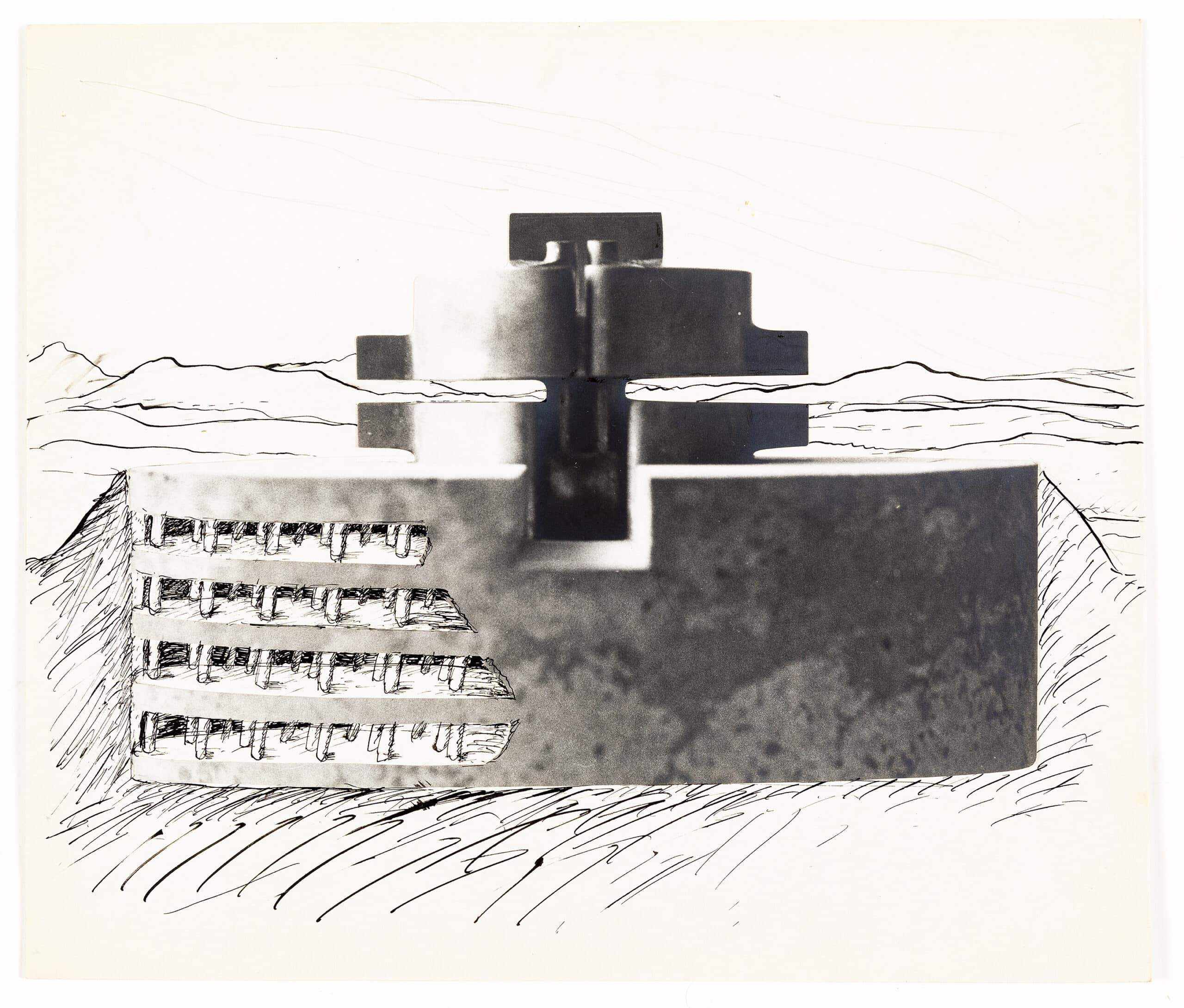

On June 28, 1969, the four members of the Viennese collective Zünd-Up presented their student project, The Great Vienna Auto-Expander, for Karl Schwanzer’s studio at the TH Wien.[2] Their proposal envisioned a monumental parking garage, hovering over Karlsplatz in the shape of a giant pinball machine, with tunnels protruding outwards into the city fabric.[3] Dressed in black trousers and white T-shirts emblazoned with a goggle-like Zünd-Up logo on their backs, the group staged the presentation as a happening beyond the confines of the university. Rather than a conventional academic studio crit, the jury convened in the Am Hof underground parking garage in the city centre, gathered around a multimedia spectacle. The show featured a furniture-sized black model, a slide show with diagrams and collages, and plans and sections mounted on the walls of the parking garage’s car wash boxes. In addition to studio instructors and students, around forty members of the Harley-Davidson and Norton motorcycle club, invited by Zünd-Up, attended the event. Amid the roar of throbbing engines, the scent of gasoline, and the electrifying riffs of Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones, the performance transgressed the conventional boundaries of architecture as a medium and discipline.

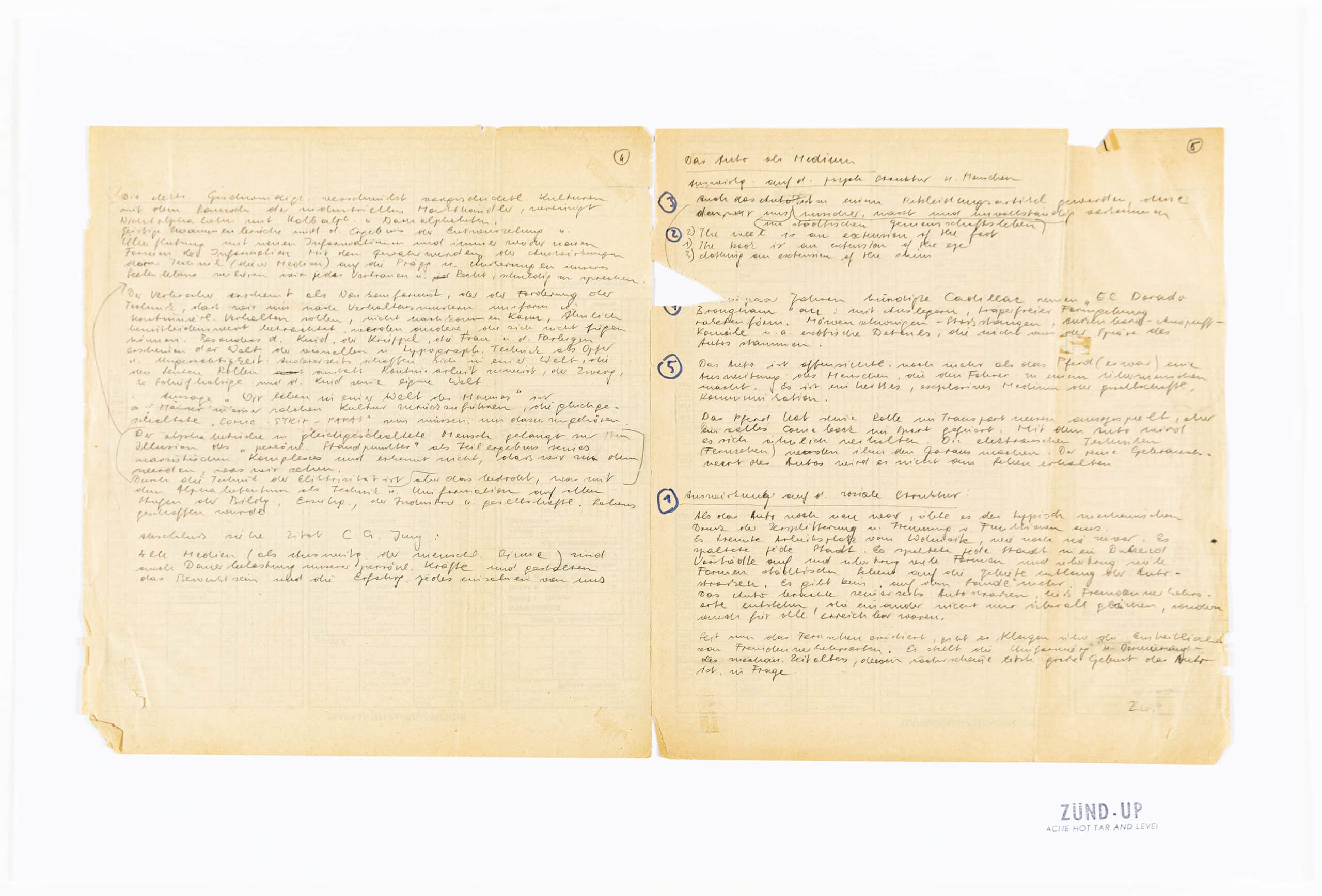

This staging of the jury amplified an empathic engagement with the choreography of the ‘happening’ inside the ‘auto-flipper,’ which was grafted onto an Easy Rider scenario or envisioned as a cyborg-like fusion of humans and cars.[4] Accelerated by the pulses of the mediatic architectural machinery, the garage—also referred to as the ‘car dream fungus’—immerses the driver in a hallucinatory pin-ball game, ricocheting them through a dense program: a ‘simulation’ of extra-ordinary beauty experiences, a ‘super service’ that tunes up automobiles into race cars, demolition derbies, light shows, and even launches into an airborne state–a privilege reserved for Dragstar choppers—via two tunnels, with Vienna’s Stephansdom as the final landing point. Referencing Marshall McLuhan’s assertion that ‘the car has become an article of dress without which we feel uncertain, unclad, and incomplete in the urban compound,’ Zünd-Up pictures the car as a ‘second skin, a body part extension of men’—only to invert this idea, posing the psychological question: at what point do humans become servomechanisms of machines?[5] As a ‘catalyst of behavioural mechanisms in industrial society,’ the car serves as a model for architecture’s dissolution into a ‘hot’ communication medium—one that intensifies speed and sensory immersion while diminishing active participation.

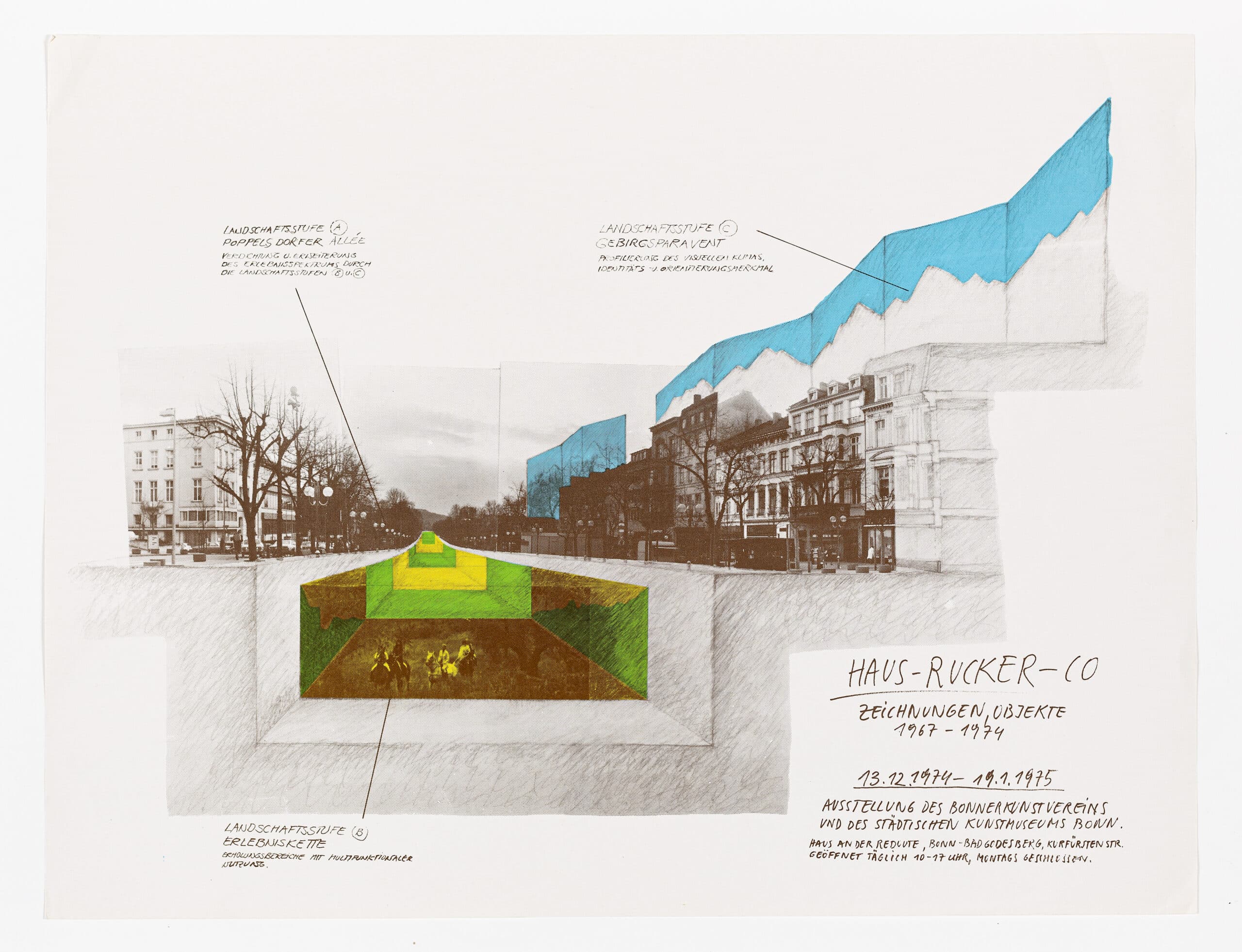

The extensive diagrams and summary statements of Zünd-up’s manifesto project neither mention nor explicitly promote the notion of ‘utopia’. Similarly, the word ‘utopia’ is absent from the manifesto of the closely linked architectural collective Haus-Rücker-Co, Provisional Architecture (1976). Instead, Haus-Rücker-Co asserts that their imagined architectural environments should be understood as ‘creative concepts which translate all-embracing structures into adequate media.’[6] Here, the ‘creative concepts’ of Haus-Rücker-Co and Zünd-Up explode into media, echoing Hans Hollein’s famous 1968 proclamation: ‘Alles ist Architektur.’[7]

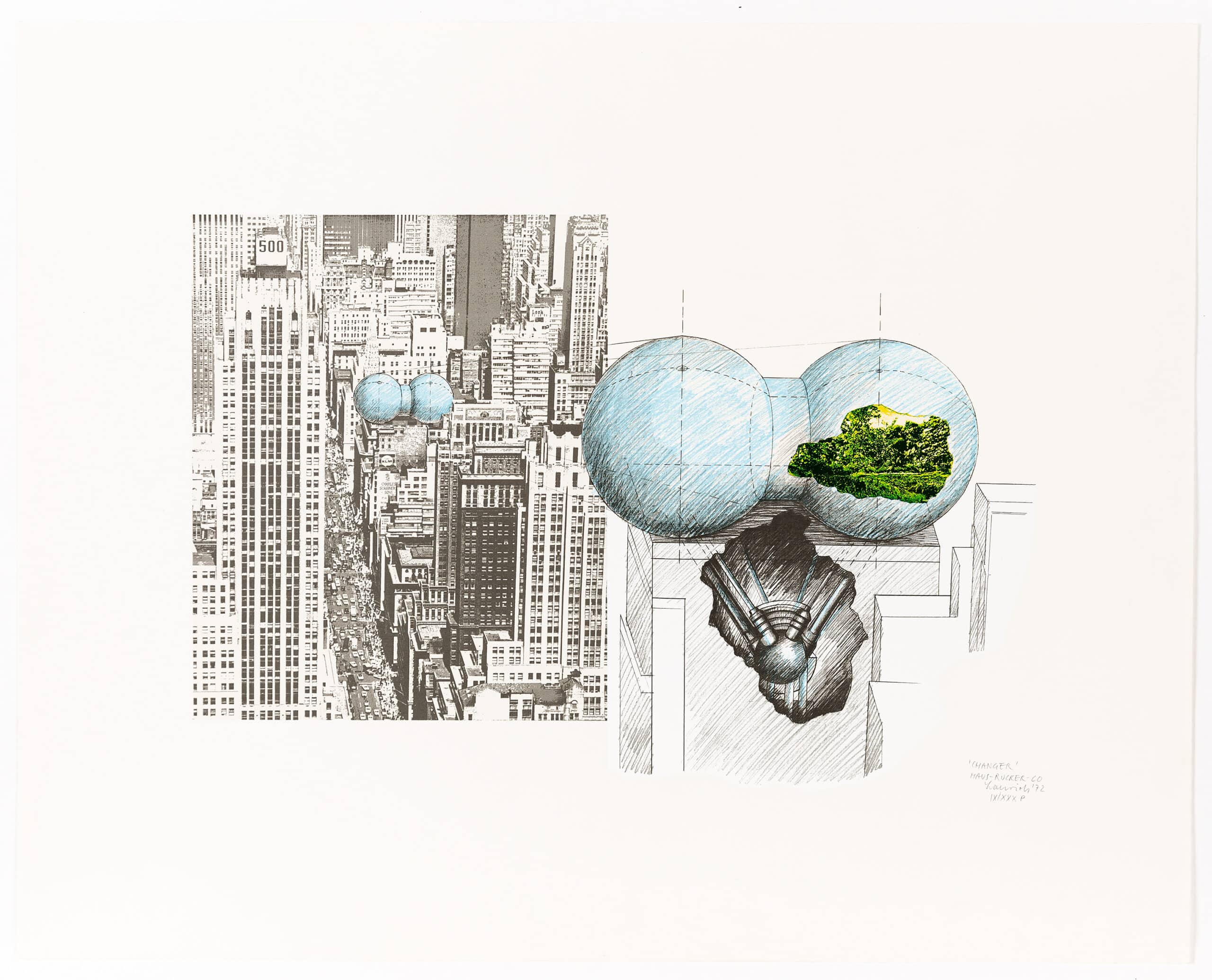

However, recent publications such as Utopia Reloaded or Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia have rightfully argued that this visionary Viennese architecture was, in fact, infused with a counter-cultural utopian ethos.[8] Utopia traditionally signifies a ‘no-place’—an insular, self-contained territory detached from the external world—where the epistemic relations of the outside, namely the social and economic systems of society, are topologically mapped onto the inside, forming an idealised ‘future’ society. All utopian visions, to some extent, seek to rewrite this interplay between interior and exterior. Within the Viennese avant-garde, utopia and its inside-outside dynamic became the focus of an original thought experiment. A key indicator of this conceptual exploration is the Viennese scene’s deep fascination with pneumatic bubbles, jet pilot helmets, and other enclosures that blur the boundaries between the body and its surrounding environment. Esther Choi, for example, interprets Haus-Rücker-Co’s pneumatic bubbles as a ‘utopian model of resistance outside of modernist opposition’—one that hinges on a delicate, membrane-like equilibrium with the very institutional authority it critiques.[9]

So, what is Zünd-Up’s utopian sphere—its extraterritorial ‘no-place’, from which speculative re-imagination unfolds? The utopian outlook of Auto-Expander is embedded in its humorous projection of architecture—either as part of a vastly expanded, networked environment of mobility or as a compressed capsule that is the car itself. Its visionary architecture operates through a dual movement: an expansive deterritorialisation in a tunnel-like tele-communication environment, coupled with an opposite pull towards isolation inside a sealed-off automobile.[10] At the centre of this paradox stands the inverted underground garage positioned above Karlplatz—an inversion, of sorts, of Walter Pichler’s Underground City projects from the early 1960s. Regardless of the scale of these disjunct machine-bodies, the ‘ghost’ of utopia persists—not as an infinite totalising possibility, but in the actual constraints of these spaces and the contained moments of their happening.[11] Humans, in this vision, become voluntary prisoners of diverse, fragmented worlds—each shaped by boundless possibilities of technology.

The most dystopian aspect of this expansive architecture, however, lies in its suggestion that post-Fordist, bio-political machinery penetrates not only the built environment but also our inner lives. The modernist utopia being interrogated here is not merely an architectural ideal but the reality of human experience—one in which the pinball game serves as a metaphor for society itself. In The War of Dreams (1997), Marc Augé argues that dreams, myths, and fictions are contested spaces, shaped by media, power structures, and global forces.[12] In a world where the private interior realm of thought is monitored while the public exterior is simulated, Zünd-Up’s mode of storytelling reclaims a space for critical imagination.

- Wolf Vostell and Dick Higgins. Fantastic Architecture (New York: Something Else Press, 1970), 9.

- My sincere thanks to Camille de Jerphanion for broadening my research interest in the Viennese scene of Zünd-Up, Haus-Rucker-Co, and Missing Link, as well as for gathering materials as part of the mini-ARC scholarship at ULB.

- Erik Wegerhoff, ‘Zünd-Up’s Dragster-Föhre’ in Desley Luscombe, Helen Thomas and Niall Hobhouse (eds.), Architecture through Drawing (London: Lund Humphries, 2019), 92-99.

- The word ‘happening’ is used in the diagrammatic section of the project: Martina Kandeler-Fritsch, Zünd-Up. Acme Hot Tar and Level (Vienna: Springer, 2001), 76.

- A fragment of this quote in German is found in the diagram in: Martina Kandeler-Fritsch, 76.

- Haus-Rücker-Co, Provisional Architecture. Medium of Urban Design (Düsseldorf: Haus-Rücker-Co, 1976), 3.

- Hans Hollein, ‘Alles ist Architektur,’ Bau 1-2 (1968), 2.

- Katja Blomberg, Haus-Rücker-Co: Architectural Utopia Reloaded (Köln: Walther König, 2015); Andrew Blauvelt (ed.), Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2015).

- Esther Choi, ‘Atmospheres of Institutional Critique: Haus-Rücker-Co’s Pneumatic Temporality’ in Hippie Modernism, ed. by Andrew Blauvelt, 31-43.

- This argument is indebted to Chapter 3 ‘Everything is Architecture’ in Buckley, Craig. Graphic Assembly: Montage, Media, and Experimental Architecture in the 1960s (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019) 125-183.

- Martin Reinhold, Utopia’s Ghost: Architecture and Postmodernism, Again (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

- Marc Augé, La guerre des rêves. Exercices d’ethno-fiction (Paris: Seuil, 1997).

Wouter Van Acker is an engineer-architect and associate professor at the Faculty of Architecture La Cambre Horta of the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), where he teaches architectural theory and a Master’s design studio on adaptive reuse. Before he was a Lecturer at Griffith University and doctoral and postdoctoral researcher at Ghent University. He has co-edited different journal issues and volumes among which Architecture and Ugliness (Bloomsbury, 2020) and the issue ‘Untimely Teachers’ for Architectural Theory Review (2024).