The Ultimate Climes of John Lautner (1986)

Who would have guessed his direction when he built his first house – not I. Beware of listening to what an architect says he is doing; watch instead what he does. He may be writing a new history.

In 1954, he told a story about the autumnal trek of Frank Lloyd Wright and his apprentices from Spring Green, Wisconsin, to Taliesin West in Arizona, with a stopover en route at Wright’s 1916 Allen house in Wichita, Kansas.

‘There was a feeling of joy and repose that I never forgot’, Lautner said. ‘That is something I try to achieve in all my houses’.

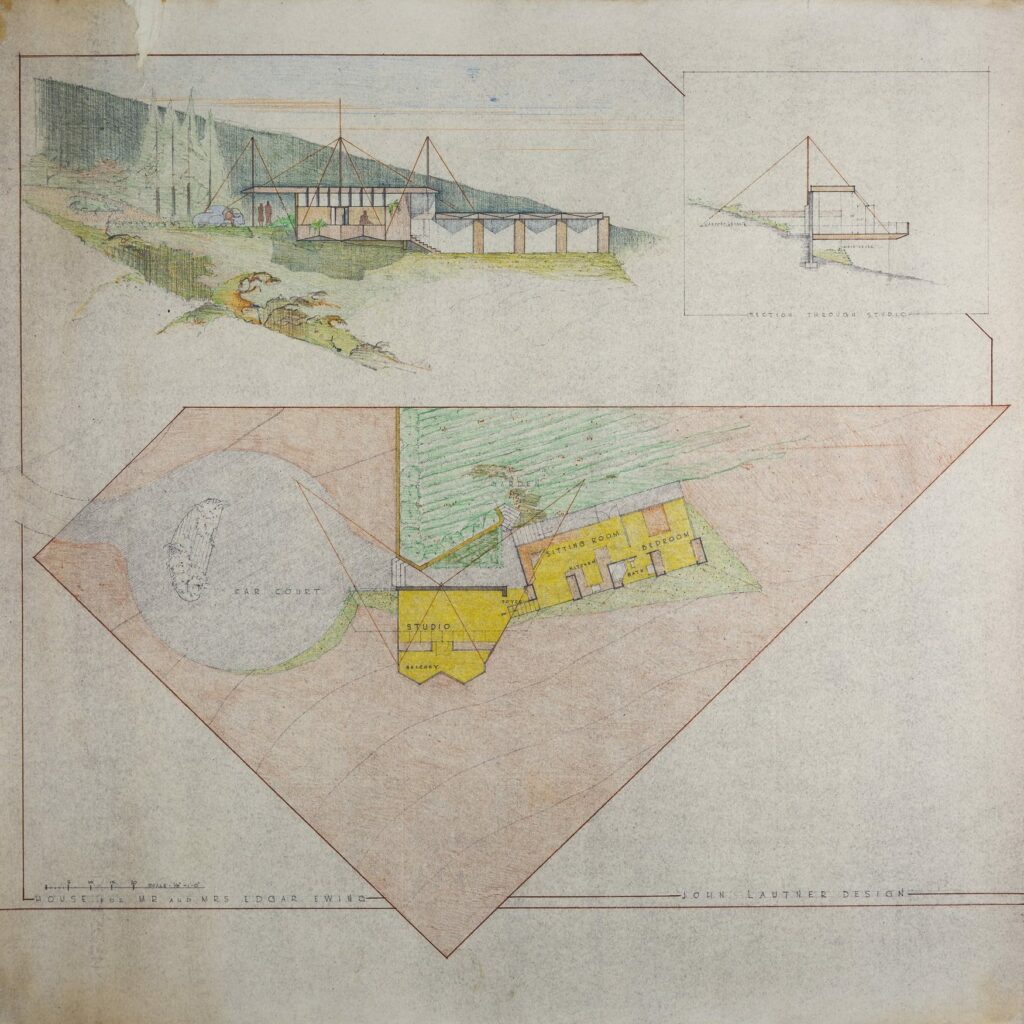

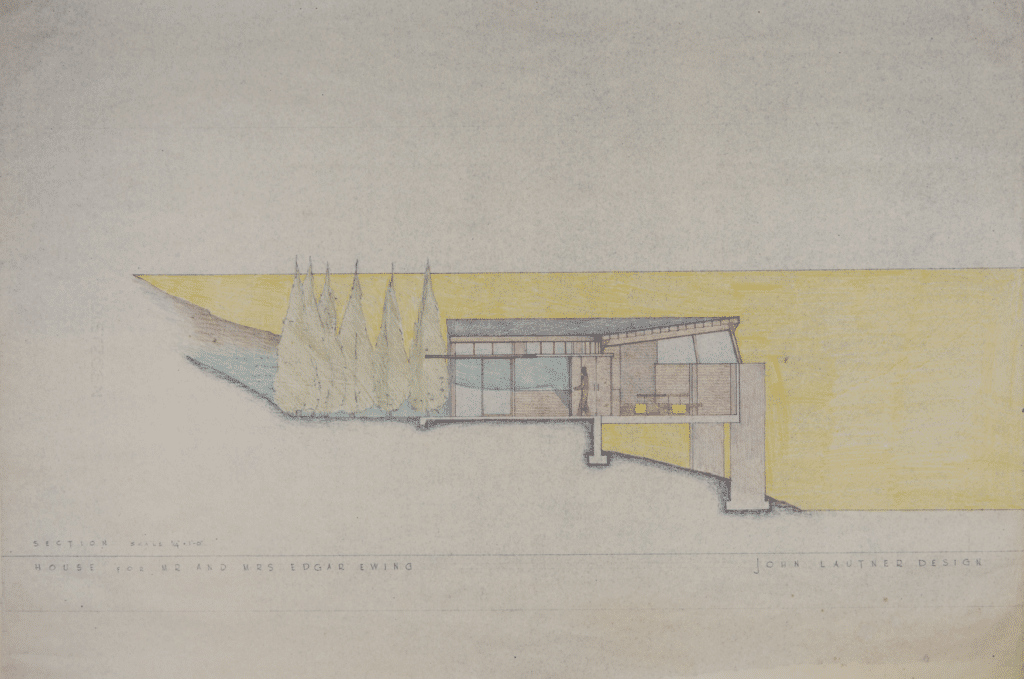

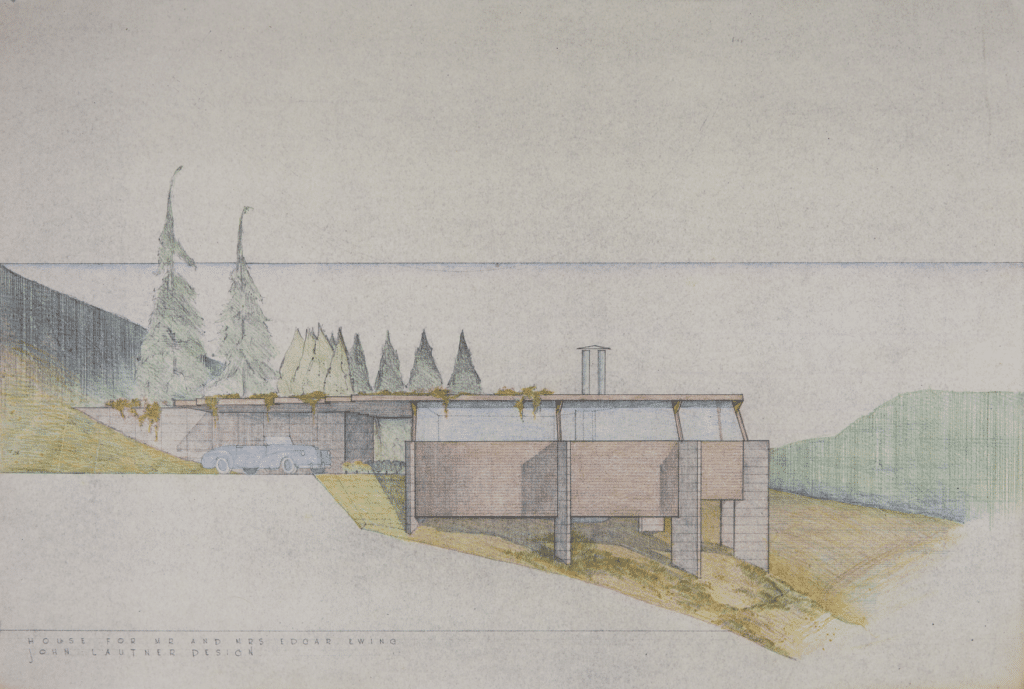

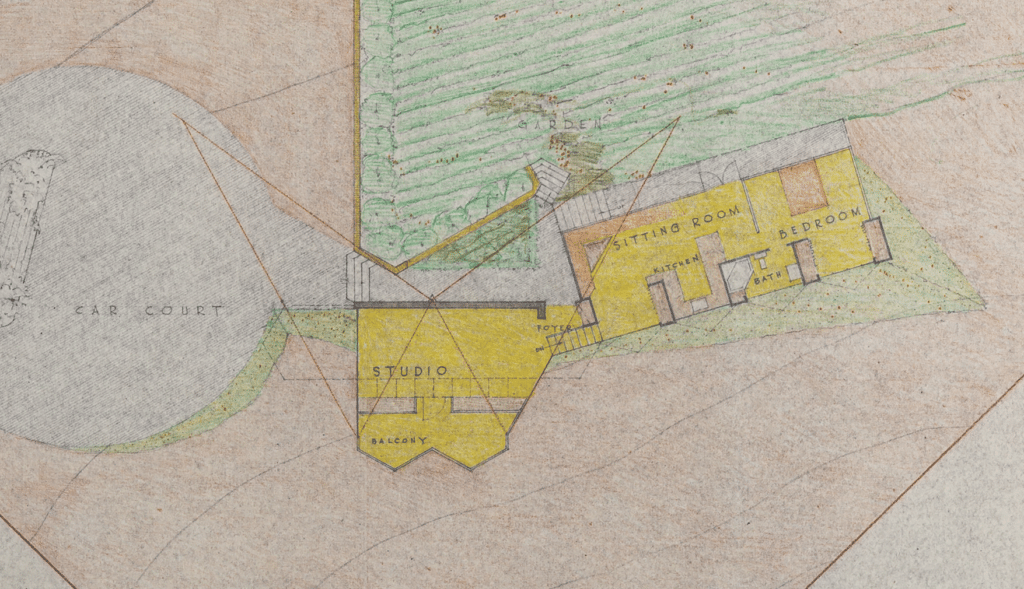

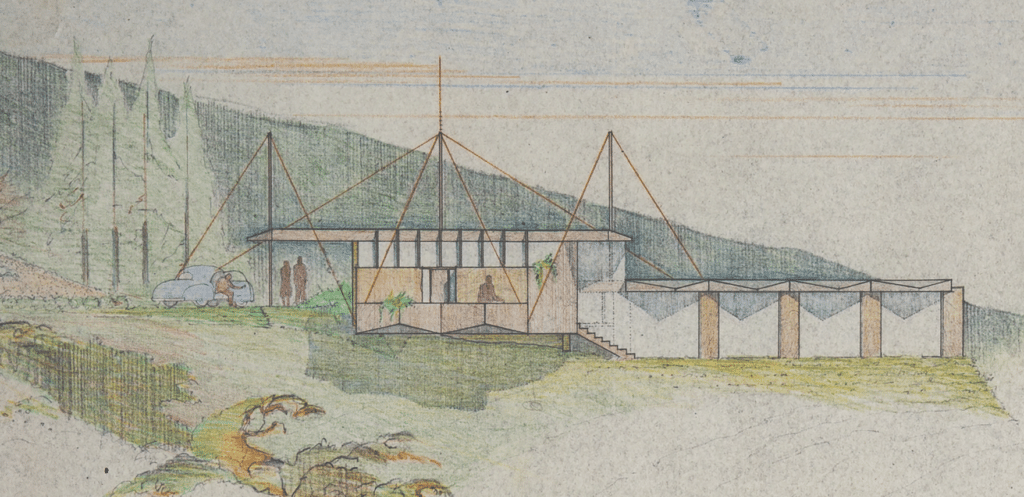

But instead of repose, his houses are thorny with ideas, ideas that wake up the eye and astonish the mind. Instead of wood in long serene planes, Lautner curved it around a circular mass in the 1950 Foster house, suggesting that the wood wanted to be plaster. There were a few of Wright’s sheltering roofs. Lautner’s were usually independent of the walls. He supported the Maurer rood on what might be a kit of parts from airplane wings; he exposed steel bow trusses shaped like snowshoes in the Gantvoort house. For a Malibu house on a narrow lot, he sliced an arch in two and hung a house from it; he stepped up mushroom roofs to make a series of gently ascending pads.

But repose, no. The engineer was lurking in the artist.

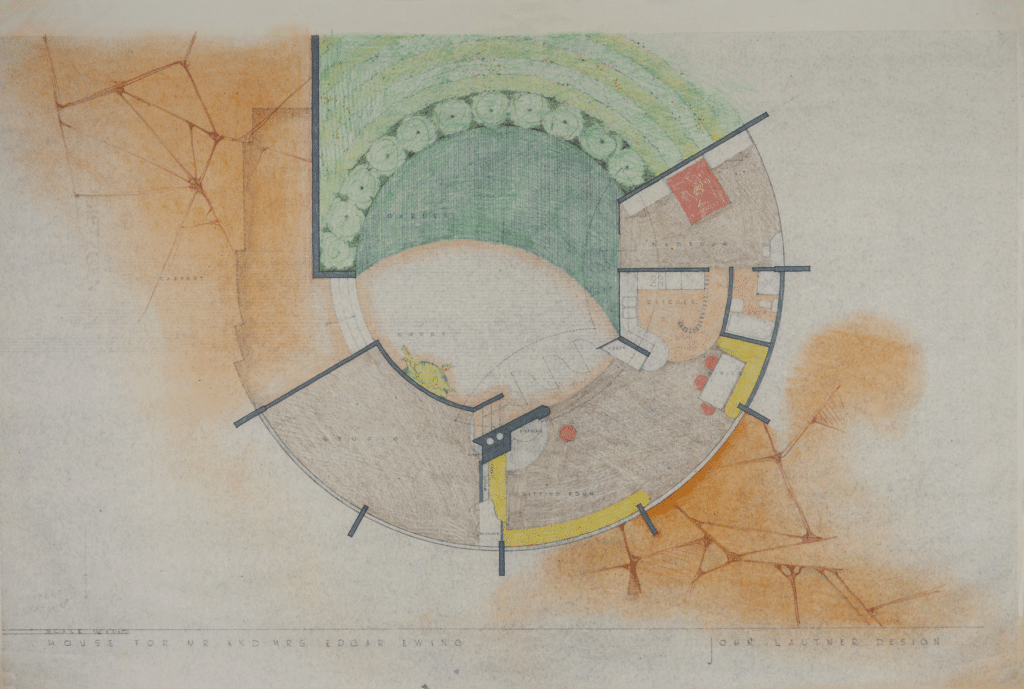

The turning point was Silvertop. Architects usually find lessons to be learned from a skimpy budget; Lautner learned from an overflowing one. The more the client of Silvertop indulged in the house, the faster Lautner learned how to orchestrate a large composition. Silvertop is the progenitor of all the houses in this exhibition. The mind that conceived them is as a supple as a spline; the instrument that recorded them is a compass with an ever-changing radius.

Silvertop was closer to Mexico than Taliesin: The Cuernavaca houses with three-walled living rooms, the fourth wall simply storm curtains to be drawn during the seasonal rains; the Mexico of Félix Candela’s thin concrete shells of the Cosmic Ray Pavilion, of churches, factories, restaurants. ‘The Mexicans are not afraid of architecture’, Lautner said.

Nor was Lautner. Walls disappeared, roofs billowed and sailed.

Now something new was happening to Lautner. Taliesin and Mexico are still present but a new breath blows. Compare two houses on adjoining lots, one by the president of Taliesin Associated Architects, its long, low, gabled, and shingled roof bespeaking repose, its glass bringing in a placid sea. Lautner’s house under construction next door is a scene out of Piranesi. The first quick glimpse is of arches riding the landscape like the aqueducts in Zacatecas; to the right is a curved and baffled road, rising like a fist to living quarters almost hidden above the arches. On the left is a thirty-five-foot-high tapered concrete wall from which reinforcing rods now protrude, rods from which a guest room might eventually be hung.

The benign Taliesin house reminds one that the angle of the earth’s repose is 30 degrees. Lautner’s site is history run backward to the Middle Ages. The same sun shines on both, but in the Lautner house the segments of the sea between the arches are a brooding blue. The high wall extends below grade to a door as sombre as the ‘legended tomb’ of Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘Ulalume’.

Lautner has spun a spell which relates little to architectural history or to the present. It relates more to poetry then to houses. The dying and renewing rhythm of the walls creeps into the sustained rhythm of ‘Ulalume’.

These were the days when my heart was volcanic

As the scoriac rivers that roll–

As the lavas that restlessly roll

Their sulphurous currents down Yaanek

In the ultimate climes of the pole.

Extracted, with permission, from Piecing Together Los Angeles: An Esther McCoy Reader, published by East of Borneo Books © 2012. The publication is available at East of Borneo.

– Nicholas Olsberg