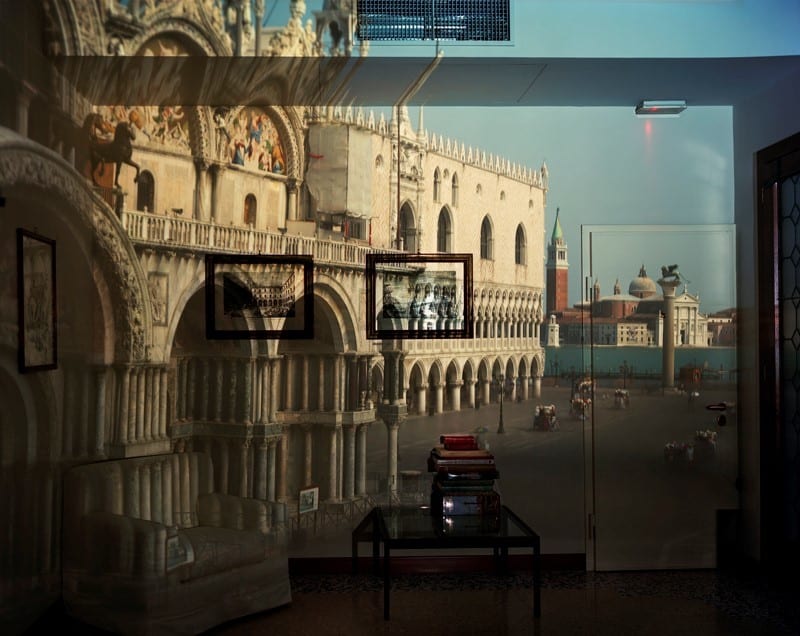

Abelardo Morell

In 2006 Abelardo Morell was invited by a collector with a Palazzo in Venice to photograph a camera obscura image of the Grand Canal in his mother’s bedroom. Morell returned to the city a year later. His host, pointing at a window in a Canaletto painting, said he knew a guy who worked in an office overlooking the Piazza San Marco and that he could use his room to take a photograph—this photograph.

Morell first started experimenting with camera obscura techniques in his living room in 1991. He covered all his windows in black plastic to achieve total darkness, then cut a small hole in one of the coverings to allow an inverted image of the view outside to project onto the back walls of the room. To push the potential of the process, he began to use colour film and a lens over the hole in the window to create a sharper, brighter image. In the photograph above, as with others, he often uses a prism so the projection comes in right side up. In the beginning, he would use a large-format camera and exposures took about eight hours. Now, making the most of digital technology, the exposure time has shortened considerably, which in turn made it possible to capture more momentary light, and so people or birds or clouds.

In Robert Adams’s book on the meaningfulness of art, he shows how Morell’s photograph of the inside of an attic, with the sea reflected in, emotionally correlates to descriptions of the Ramsays’ house in Virginia Woolf’s novel To the Lighthouse. Both writer and photographer capture how ‘nature reenters our carefully protected spaces’ in immortal rhythm, ‘restoring to the temporal the timeless’.

‘Now, day after day, light turned, like a flower reflected in water, its sharp image on the wall opposite… so loveliness reigned and stillness.’ And this, among the most beautiful passages in the novel: ‘Nothing it seemed could break that image, corrupt that innocence, or disturb the swaying mantle of silence which, week after week, in the empty room, wove into itself the falling cries of birds, ships hooting, the drone and hum of fields, a dog’s bark, a man’s shout, and folded them round the house in silence.’ [1]

Note

- Robert Adams, Art Can Help (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017), p.21.

– Paul Stirton